Abstract

This study investigated the wound healing properties of the aqueous extract of Morinda tinctoria Roxb leaves in rats. The study also provides information on the purification, qualitative, and quantitative analysis of phytochemical components present in M. tinctoria Roxb. Wound contraction and period of epithelialization was determined and topical application of M. tinctoria Roxb aqueous leaf extract showed better healing than orally treated and control groups. The results suggest that the efficacy of M. tinctoria Roxb aqueous leaf extract as a wound healing agent and can also be used as a therapeutic agent for internal as well as external wounds.

Keywords: Morinda tinctoria Roxb, Aqueous extract, Phytochemicals, Wound healing

Introduction

Traditional medicinal plants with rich phytochemical components are commonly used to obtain preparations beneficial for significant wound healing purposes comprising a comprehensive area of various skin-related diseases (Maver et al. 2015). The role of medicinal plants and their wound healing activity was observed in numerous studies (Elzayat et al. 2018; Dons and Soosairaj 2018; Pereira et al. 2018; Dorjsembe et al. 2017; Singh et al. 2017). Morinda tinctoria Roxb (Family: Rubiaceae) which forms the subject of this study is traditionally used in Ayurveda and Siddha systems for their phytochemical profile and therapeutic potential. It is commonly called as Indian mulberry or aal or nuna in India. It is a small tree with distinguished medicinal properties. Literature survey reveals that traditionally the leaf juice is given orally before food for easy digestion (Muthu et al. 2006). The expressed juice of leaves is externally applied to gout to relieve pain. The leaves are administered internally as a tonic and febrifuge (Kirtikar and Basu 1935). The n-hexane, dichloromethane, and methanol extracts of the leaves were shown to possess anti-bacterial and antifungal activities (Jayasinghe et al. 2002). The petroleum ether extract showed anti-convulsant activity (Kumaresan and Saravanan 2009). Anti-convulsant, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective effect, and anti-microbial activity of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves have been reported (Deepti et al. 2012). Early studies reported that the extract of leaf, root, and fruits of this plant showed anti-bacterial, analgesic, anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, astringent, laxative, sedative, and hypotensive (lowers blood pressure) potentials (Subramanian et al. 2013; Deepti et al. 2012; Sreena et al. 2011; Amerasan et al. 2015; Sivakumar et al. 2018). The extracts of fruits are commercially available in the form of juice which claimed to reduce hypertension, painful menstruation, arthritis, gastric ulcers, diabetes, and depression. However, the effect of aqueous leaf extract of M. tinctoria Roxb on wound healing is not yet fully understood. Therefore, the current study is an attempt to investigate the wound healing activity of the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves.

Materials and methods

Preparation of aqueous leaf extract of M. tinctoria Roxb

Fresh and healthy leaves were collected from Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India. The leaves were washed thoroughly with tap water and rinsed with 70% ethanol and blotted using filter paper to remove excess water droplets and allowed to air-dry under shade at room temperature. The dried leaves were then grounded well-using pestle and mortar into a coarse powder. The ground leaves were collected and packed using Whatman filter paper No. 1. The crude aqueous extract of plant leaves was obtained by using Soxhlation method (Rex et al. 2015).

Phytochemical analysis, quantification, and purification of aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves

Preliminary phytochemical chemical tests and quantification of phytochemicals were conducted on the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves using standard methods (Edeoga et al. 2005; Mallikharjuna et al. 2007). The purification of phytochemicals (alkaloids, glycosides, and flavonoids) was done using organic extraction following standard protocols (Kumar et al. 2006; Govindachari et al. 1969). The authentic samples used in this study are gallic acid (phenols), atropine (alkaloids), rutin (flavonoids), tannic acid (tannins), ginsenoside (saponins), and steviol (glycosides). All the chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA.

Animal used

About 18 healthy adult male Wistar rats of 2–3 months old (weight 150–250 g) were used for this study. After 2 weeks of acclimatization, the animals were allocated into three experimental groups (Control, Test-Oral, and Test-Local) of six animals each (n = 6). The protocol for the study was approved by Animal Ethical committee, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India.

Excision wound model

The animals from each group were anesthetized by the open mask method using anesthetic ether. Depilation of the rats was done on the dorsal side. The excision wound was inflicted by cutting away a 100 mm2 skin from the shaved area (Taranalli et al. 2004). Excision wound was left undressed. Topical and oral application of the plant extracts to the divided groups viz. Control, Test-Oral, and Test-Local, respectively, were done once daily until the wound healed completely. Wound contraction and epithelialization period of control and experimental wounds were monitored and determined.

Collection of blood

Blood was collected before (0th day) and after (3rd, 7th, 10th, 15th, and 20th days) the wound creation. The rats were anesthetized and were restrained properly in a rat restraint platform. Blood was collected from rat by embedding the tail in 45 °C water bath and the tail was wiped with xylene for the blood vessels to dilate. Using sterile scissors about 1 mm of the tail end was cut and about 0.5 ml of blood collected in a sterile container without anticoagulant. The blood samples were allowed to incubate at room temperature for overnight. The sample was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min and the serum was transferred to a fresh container.

Succinylated gelatin assay and SDS-PAGE zymography for MMP-2 and MMP-9

Succinylation of gelatin

Gelatin was succinylated using the procedure described previously (Rao et al. 1997). Gelatin was dissolved in 50 mM sodium borate buffer, pH 8.5, at a concentration of 20 mg/ml. An equal amount of succinic anhydride was then gradually added to the solution and the pH of the reaction was maintained at 8.0–8.5 by the addition of 1 N NaOH. The succinylated gelatin was then dialyzed extensively against 50 mM sodium borate buffer, pH 8.5.

Dialysis

The tubing was submerged in the running tap water for 3–4 h and treated with 0.3% sodium sulfide solution for 1 min at 80 °C. The tube was washed with hot water at 60 °C for 2 min, washed with 0.2% H2SO4, and rinsed with water. The tubing submerged in water and stored at 4 °C until use. About 1 ml of sample was added to the dialysis tubing and the ends were tied with thread. The tubing was submerged in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 and incubated at 4 °C for overnight with mild stirring. The sample was transferred to a fresh tube.

MMP assay

The total activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 was assayed by the method proposed (Baragi et al. 2000). Briefly, MMP-2 was assayed in 50 mM Borate buffer, pH 7.0, whereas MMP-9 was assayed in Borate buffer, pH 8.5. The total reaction volume was 1.5 ml, which contained 10 µl of serum (as enzyme source) and 200 µg of succinylated gelatin (as substrate). Blank was prepared without substrate but with appropriate buffers for each assay. The reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 30 min. 500 µl of 0.03% TNBSA (1, 2, 4-trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid) was added and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The optical density of each reaction was determined at 450 nm.

Biotoxicity assays

The animals were euthanized by anesthesia and the tissues such as liver, heart, and kidney were stored in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and were homogenized in the same buffer.

Estimation of reduced glutathione

0.5 ml of homogenate was quickly acidified immediately after homogenization with 125 µl of 25% TCA to achieve a final concentration of 5%. The tubes were placed on ice for minutes and the mixture diluted further with 0.6 ml of 5% TCA. The precipitated protein was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min. The tubes were again transferred to ice and 0.1 ml of supernatant was taken for the assay. The volumes of the aliquot were up to 1 ml with 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). 2 ml of freshly prepared DTNB solution was added to the tubes and the intensity of the yellow color formed was read at 412 nm in a spectrophotometer after 10 min. A standard curve of reduced glutathione was prepared using concentration ranging from 2 to 10 nanomoles of GSH in 5% TCA. The GSH was expressed as µg/mg protein.

Estimation of sulfhydryl group

Sulfhydryl groups were estimated by using the standard protocol (Ando and Steiner 1973) with slight modification. 0.3 ml of 1.0 M phosphate buffer and 0.2 ml of DTNB reagent were added to 1 ml of a sample containing 200 µg protein. The test tubes were allowed to stand for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was then read at 412 nm against a blank consisting of reagent mixture without DTNB.

Anti-microbial activity aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves

Antimicrobial activity of the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves was evaluated using standard agar well-diffusion method as detailed elsewhere (Collin et al. 1995; Murray et al. 1995; Ugur et al. 2010). Zone of inhibition against the tested bacterial and fungal microorganisms was measured for the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb at 1 mg/ml. Distilled water was used as a negative control, and Gentamicin for bacterial strains and ketoconazole (10 µg) for fungal strains were used as positive controls.

Results and discussion

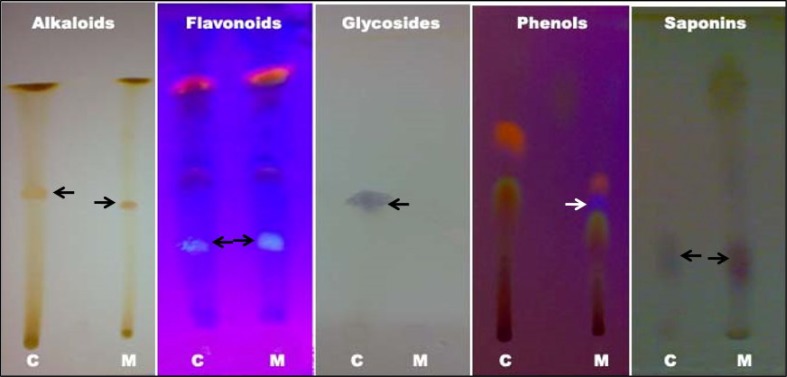

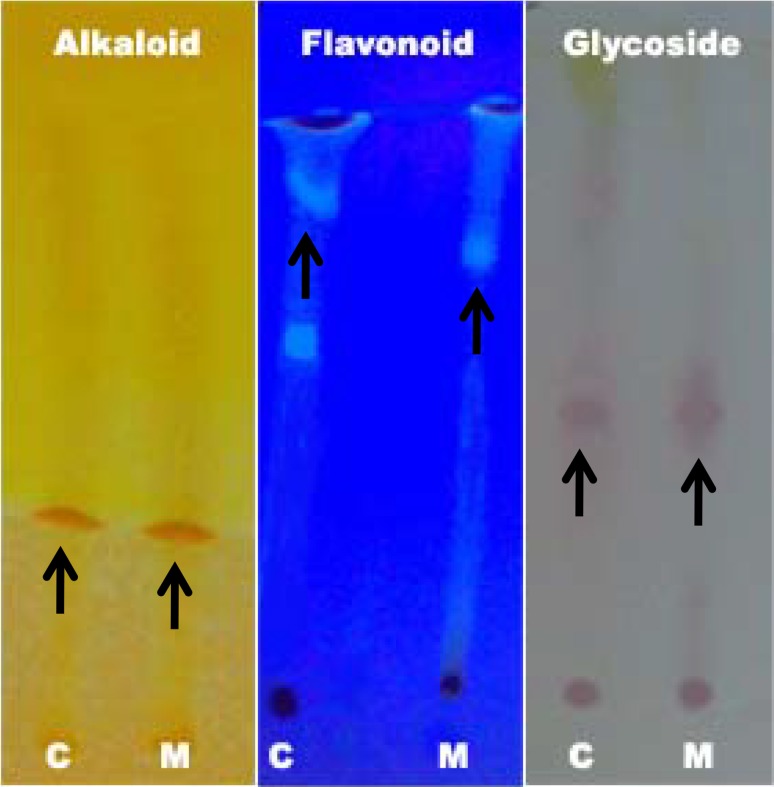

The phytochemical analysis was carried out in order to assess the potential compounds that are present in the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves. The preliminary phytochemical qualitative analysis revealed the presence of tannins, terpenoids, and alkaloids in the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves. However, the quantitative analysis revealed the presence of tannins, flavonoids, saponins, alkaloids, and phenols. Among the phytochemicals, tannins are found to be about 9.7%, followed by alkaloid (0.55%), saponin (0.4%), flavonoids (0.2%), and phenol (0.03%) (Table 1). The TLC analysis of phytochemicals revealed the presence of alkaloids (Rf 0.55), flavonoids (Rf 0.28), phenols (Rf 0.54), and saponins (Rf 0.24) (Fig. 1; Table 2). An attempt was made to purify alkaloids, flavonoids, and glycosides from the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves. The organic extraction methods were employed for the purification of these phytochemicals. The TLC analysis of purified compounds (Fig. 2; Table 3) revealed a single spot on each corresponding plate. The Rf value for each purified compound was well-matched with the authentic samples mentioned above. The Rf values for alkaloid was 0.44, for flavonoids 0.72 and for glycosides 0.54. Flavonoids in its pure form migrated along with the solvent front and the Rf value was higher in purified form when compared to the Rf value in the crude form. The mobility difference in flavonoids may be due to the removal of carbohydrates from the flavonoids using β-glycosidase in the purification step. In general, almost all flavonoids will be bound to carbohydrate moieties. Thus, the free flavonoids will move without any hindrance compared to the carbohydrate bound flavonoids.

Table 1.

Phytoconstituents of aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves

| Phytochemical constituents of Morinda tinctoria Roxb leaf extract | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tannin | Phlobatannin | Saponin | Flavonoid | Terpenoid | Cardiac glycoside | Alkaloid | Phenol | |

| Qualitative analysis | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | ND |

| Quantitative analysis (%) | 9.7 | ND | 0.4 | 0.2 | ND | ND | 0.55 | 0.03 |

Yes presence of compounds, No absence of compounds, ND not done

Fig. 1.

Phytochemical analysis of aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves using thin layer chromatography. Black and white arrow indicates the presence of corresponding phytochemical constituents. C authentic sample, M aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves

Table 2.

Rf values for phytochemicals of M. tinctoria Roxb aqueous leaf extract

| Phytochemicals | Rf values for phytochemicals | |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic sample | M. tinctoria Roxb extract | |

| Alkaloids | 0.56 | 0.55 |

| Flavonoids | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| Glycosides | 0.54 | – |

| Phenols | – | 0.54 |

| Saponins | 0.24 | 0.24 |

Fig. 2.

Thin layer chromatographic analysis of purified phytochemicals of aqueous leaf extract of M. tinctoria Roxb

Table 3.

Rf values for purified phytochemicals of aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves

| Phytochemicals | Rf values for phytochemicals | |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic sample | Morinda extract | |

| Alkaloids | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| Flavonoids | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| Glycosides | 0.54 | 0.54 |

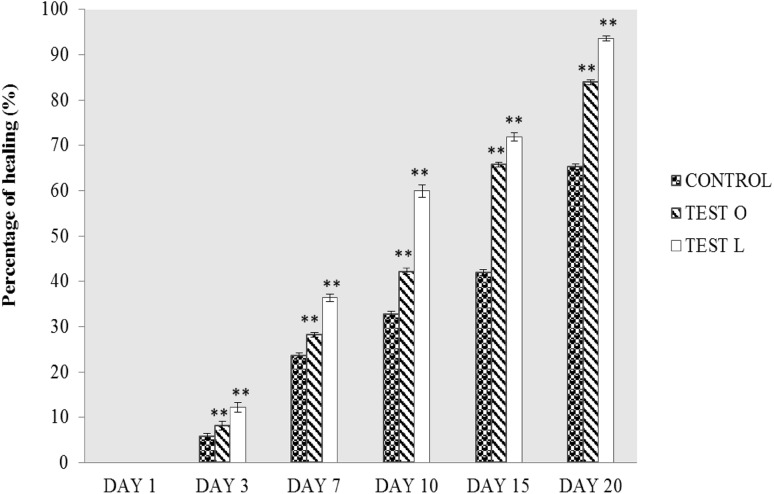

The healing of wound was observed in all groups, but the effective healing or fast recovery was observed in Test rats treated by a local application (Fig. 3). At the end of the 20th day, the healing was almost 93.56% in test rats treated by local application, whereas the healing was 83.92% in test rats treated by oral administration, and the healing was only 75.35% in control.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of wound contraction of rats treated with M. tinctoria Roxb extract (Test O: oral administration of test rats with M. tinctoria Roxb leaf extract, Test L: local administration of test rats with M. tinctoria Roxb extract). Values are represented as mean ± SEM with triplicate estimations (**P < 0.01)

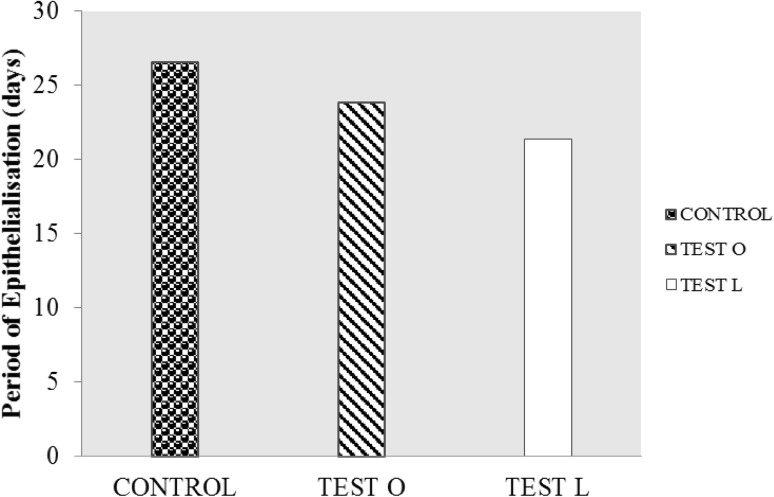

The lesser period of epithelialization was observed in local administration Test groups than oral administration and control groups (Fig.4). This suggests that aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves are effective in wound healing and the efficacy was better in local application than by oral administration.

Fig. 4.

Period of epithelialization of rats treated with aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves

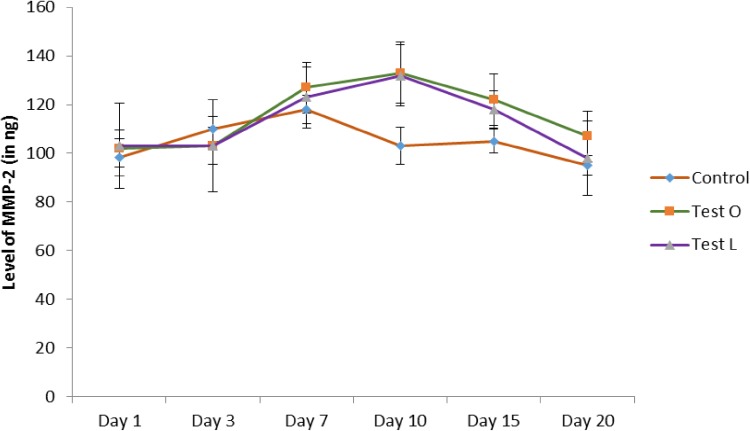

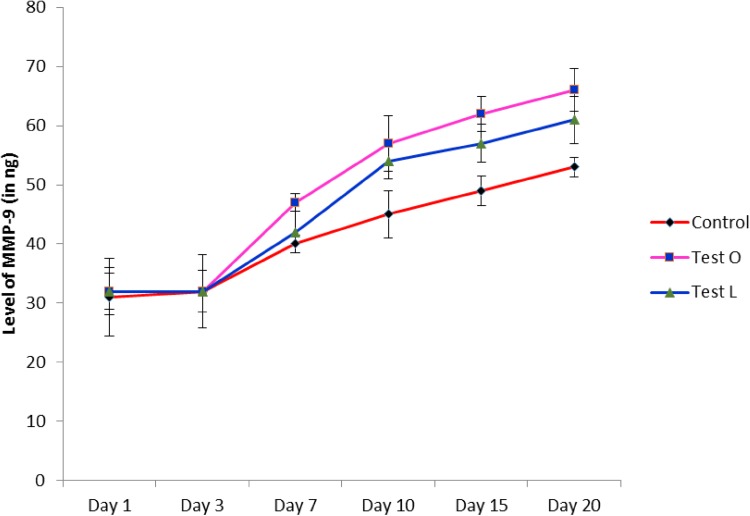

The role of matrix metalloproteinases in wound healing has been elucidated in many of the reports. These enzymes are found to be working on both inflammatory as well as the proliferative phase of wound healing. It was suggested that MMP-2 was expressed during inflammatory phase by polymorphoneutrophils and macrophages, whereas MMP-9 was expressed in proliferative phase by fibroblast and endothelial cells in order to remodel the denatured collagen at the wound site. Thus, the role of MMP-2 and MMP-9 was analyzed in this study during the wound healing process. Bleeding was done in all rats before and after the creation of wound (1st, 3rd, 7th, 10th, 15th, and 20th days). The serum was separated and checked for MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity using Succinylated gelatin assay, which is a well-known method for the quantification of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in any biological materials. Results from Succinylated gelatin assay for MMP-2 revealed that there was an increase in MMP-2 activity in both Tests at the days 7, 10, and 15, and peaked at day 10 when compared to control (Fig. 5). MMP-9 analysis revealed that there was a drastic increase in MMP-9 activity in test groups from the day 7 till the day 20 when compared to the control. However, the MMP-9 activity was found higher in test group treated with oral administration (Fig. 6). This can be assumed that the components from the M. tinctoria Roxb extract might influence the immune system to over-act on the wound site by modulating the action of inflammatory cells. It was known that the activation of MMP-9 is dependent on the levels of MMP-2. Otherwise, the MMP-2 activates the inactivated form of MMP-9 to activated form. Thus, due to the immune activation by components from M. tinctoria Roxb extract, might increase the concentration of MMP-2 during inflammatory phase, whereby increase the activated form of MMP-9 in the serum.

Fig. 5.

Activity of matrix metallo proteinases-2 (MMP-2) during wound healing (Test O: oral administration of test rats with M. tinctoria Roxb extract, Test L: local administration of test rats with M. tinctoria Roxb extracts). Values are expressed in mean ± SD

Fig. 6.

Activity of matrix metallo proteinases-9 (MMP-9) during wound healing (Test O: oral administration of test rats with aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves extract, Test L: local administration of test rats with aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves). Values are expressed in mean ± SD

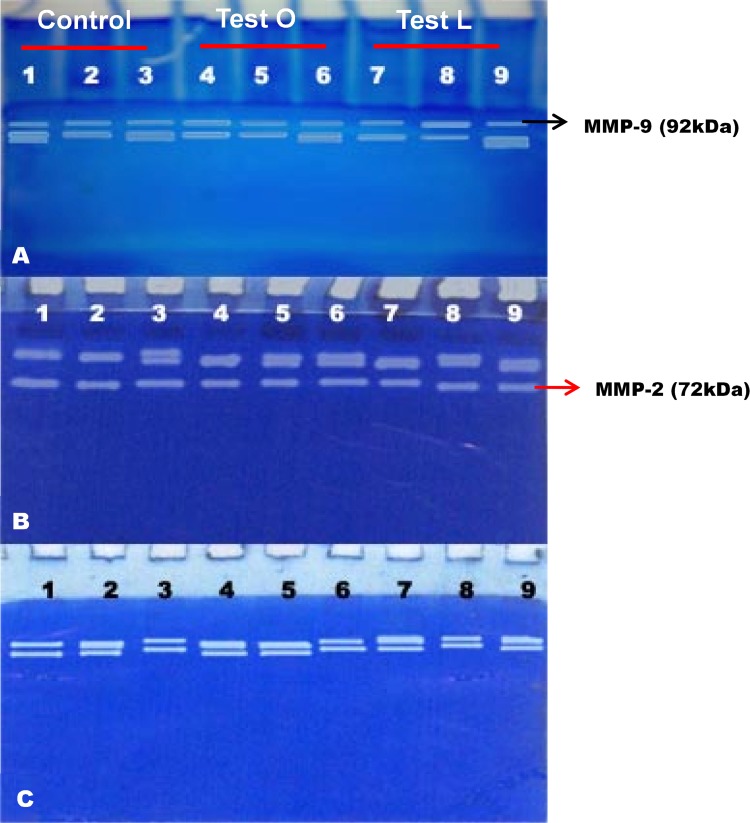

Gelatin zymography is a method based on the substrate-specific digestion of MMPs. Gelatin, which is a modified or denatured form of collagen, will acts as a substrate for MMPs when incorporated into the SDS-PAGE. Thus, the presence of MMPs in any of the sample will be identified by the digestion pattern on the SDS-PAGE against a blue background. In the present study, SDS-PAGE Gelatin zymography was carried out in order to confirm the presence of MMP-2 and MMP-9 by their molecular weights. MMP-9 is a high molecular weight molecule (92 kDa) when compared to MMP-2 (72 kDa) (Fig. 7). Results from SDS-PAGE gelatin zymography revealed the presence of these two MMPs. However, it could be observed that at the 3rd day, the level of MMP-2 was more when compare to MMP-9, which suggests that the wound healing process is at the inflammatory phase, where the immune cells might start secreting more MMP-2. At the same time, at day 10, the level of MMP-9 was found to be more and it can be assumed that the wound healing process has entered into the proliferative phase. At day 20, almost both the MMPs have reached the normal, which suggests that wound healing process is almost complete.

Fig. 7.

SDS-PAGE gelatin zymography analysis of MMPs (MMP-2 and MMP-9). a–c Analysis of MMP-2 and -9 on day 3, day 10, and day 20, respectively. Lanes 1–3: control group, lanes 4–6: test group treated with aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves by oral administration, lanes 7–9: test group treated with aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves by local application. Black arrow indicates position of MMP-9 and red arrow indicates position of MMP-2

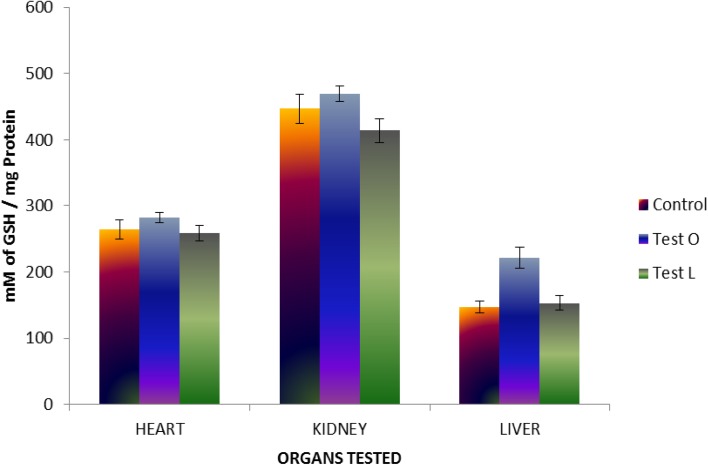

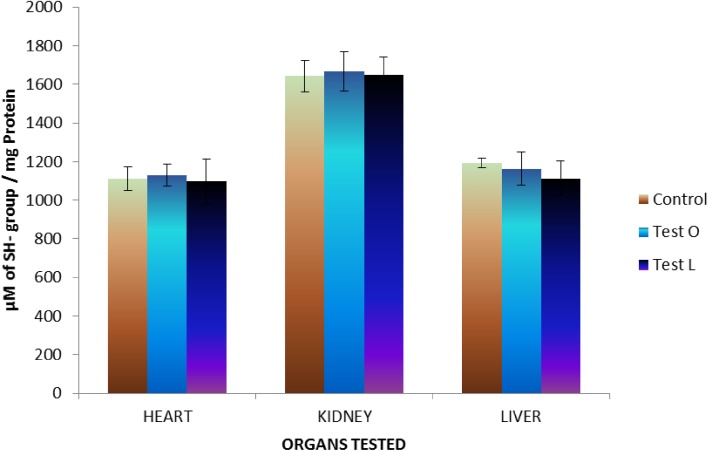

The effect of M. tinctoria Roxb aqueous extract on tissue glutathione as well as sulfhydryl groups was analyzed on three different organs, such as heart, kidney, and liver. Results of GSH assay indicated that there were no significant changes in the level of reduced glutathione in organs of both control and tests groups. However, there was an increase in the level of reduced glutathione in all organs of animals treated by oral administration (Fig. 8). This suggests that the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves might possess anti-oxidant potential as well or it might help in the induction of physiological anti-oxidants. Results of SH assay indicated that there were no significant changes in sulfhydryl group in all organs of both control and tests rats (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Changes in level of reduced glutathione (GSH) in rats treated with aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves

Fig. 9.

Changes in level of sulfhydryl groups (SH) in rats treated with aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves

Anti-microbial activity was carried out in order to check whether the wound healing activity was due to the prevention of bacterial and fungal infection by M. tinctoria Roxb extract. The antimicrobial activity of aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves was checked against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli as well as Candida albicans. There was a clear zone of inhibition around the well coated with M. tinctoria Roxb extract (Table 4). This indicates that the M. tinctoria Roxb aqueous leaf extract has good antimicrobial activity against selected bacterial and fungal pathogens. Thus, the mode of healing might be due to inhibition of microbial population in the wound site. However, there could be also some physiological mechanism responsible for effective wound healing in both oral and local administration of M. tinctoria Roxb aqueous leaf extract.

Table 4.

Antimicrobial activity of aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb

| Microbial pathogens | Zone of inhibition (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | 25 µl (MT) | 50 µl (MT) | 100 µl (MT) | |

| Bacillus subtilis | 19.23 ± 0.10 | – | – | 16.67 ± 1.81 |

| Escherichia coli | 18.16 ± 0.29 | 6.22 ± 0.78 | 12.38 ± 1.82 | 16.19 ± 1.27 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 19.89 ± 0.18 | – | 14.28 ± 1.37 | 17.65 ± 1.65 |

| Candida albicans | 20.86 ± 0.22 | 5.54 ± 1.10 | 13 ± 1.33 | 17.43 ± 1.10 |

The values indicates diameter of zone (mm). (–) No activity detected; MT: Morinda tinctoria Roxb aqueous leaf extract; gentamicin as standard for bacteria; ketoconazole as standard for fungi. The data expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Conclusion

This study provides information about the phytochemical components, antimicrobial activity, and wound healing efficacy of an aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves. It is clearly evident that phytoconstituents like flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, terpenoids, and saponins are present in the aqueous extract of M. tinctoria Roxb leaves. The investigation showed positive results for antimicrobial activity of aqueous leaf extract of M. tinctoria Roxb which encourages the possibility of using traditional medicine as a treatment to fight against microbial infections as they have opened a new avenue as a safe and more efficient therapy against the multidrug-resistant pathogens. The results suggest that the efficacy of M. tinctoria Roxb aqueous leaf extract as a wound healing agent and can be used as a therapeutic agent for external wounds.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Amerasan D, Murugan K, Panneerselvam C, Kanagaraju N, Kovendan K, Kumar PM. Bioefficacy of Morinda tinctoria and Pongamia glabra plant extracts against the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) J Entomol Acarol Res. 2015;47(1):31–40. doi: 10.4081/jear.2015.1986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ando Y, Steiner M. Sulfhydryl and disulfide groups of platelet membranes. I. Determination of sulfhydryl groups. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 1973;311(1):26–37. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baragi VM, Shaw BJ, Renkiewicz RR, Kuipers PJ, Welgus HG, Mathrubutham M, Cohen JR, Rao SK. A versatile assay for gelatinases using succinylated gelatin. Matrix Biol. 2000;19(3):267–273. doi: 10.1016/S0945-053X(00)00086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black and white arrow indicates the presence of corresponding phytochemical constituents. C: Authentic sample, M: Aqueous extract of Morina tinctoria Roxb leaves

- Collin CH, Lyne PM, Grange JM. Microbiological methods. Oxford: Butter Worth; 1995. pp. 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Deepti K, Umadevi P, Vijayalakshmi G. Antimicrobial activity and phytochemical analysis of Morinda tinctoria Roxb leaf extracts. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(3):S1440–S1442. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60433-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dons T, Soosairaj S. Evaluation of wound healing effect of herbal lotion in albino rats and its antibacterial activities. Clin Phytosci. 2018;4(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s40816-018-0065-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorjsembe B, Lee HJ, Kim M, Dulamjav B, Jigjid T, Nho CW. Achillea asiatica extract and its active compounds induce cutaneous wound healing. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;206:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edeoga HO, Okwu DE, Mbaebie BO. Phytochemical constituents of some Nigerian medicinal plants. Afr J Biotechnol. 2005;4(7):685–688. doi: 10.5897/AJB2005.000-3127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elzayat EM, Auda SH, Alanazi FK, Al-Agamy MH. Evaluation of wound healing activity of henna, pomegranate and myrrh herbal ointment blend. Saudi Pharm J. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindachari TR, Pai BR, Srinivasan M, Kalyanaraman PS. Chemical investigation of Andrographis paniculata. Ind J chem. 1969;7:306. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasinghe ULB, Jayasooriya CP, Bandara BMR, Ekanayake SP, Merlini L, Assante G. Antimicrobial activity of some Sri Lankan Rubiaceae and Meliaceae. Fitoterapia. 2002;73(5):424–427. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirtikar KRBB, Basu BD. Indian medicinal plants. Indian Medicinal Plants. 2. Dehra Dun: K.A. Longman; 1935. pp. 1294–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PS, Soni K, Saraf MN. In vitro tocolytic activity of Sarcostemma brevistigma Wight. Ind J Pharm Sci. 2006;68(2):190–194. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.25713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaresan PT, Saravanan A. Anticonvulsant activity of Morinda tinctoria Roxb. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;3(2):063–065. [Google Scholar]

- Mallikharjuna PB, Rajanna LN, Seetharam YN, Sharanabasappa GK. Phytochemical studies of Strychnos potatorum Lf-A medicinal plant. J Chem. 2007;4(4):510–518. [Google Scholar]

- Maver T, Maver U, Stana Kleinschek K, Smrke DM, Kreft S. A review of herbal medicines in wound healing. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(7):740–751. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PR, Baron EJ, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Yolken HR. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Muthu C, Ayyanar M, Raja N, Ignacimuthu S. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu, India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2(1):43. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira LOM, Vilegas W, Tangerina MMP, Arunachalam K, Balogun SO, Orlandi-Mattos PE, de Oliveira Martins DT. Lafoensia pacari A. St.-Hil.: wound healing activity and mechanism of action of standardized hydroethanolic leaves extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;219:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SK, Mathrubutham M, Karteron A, Sorensen K, Cohen JR. A versatile microassay for elastase using succinylated elastin. Anal Biochem. 1997;250(2):222–227. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex JRS, Sreeraj K, Muthukumar NMSA. Qualitative Phytoconstituent profile of Lobelia trigona Roxb extracts. Int J PharmTech Res. 2015;8(10):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Ali SS, Khan NA, Mishra A, Mishra AK. Wound healing potential of Cleome viscosa Linn. seeds extract and isolation of active constituent. S Afr J Bot. 2017;112:460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2017.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar T, Sivamaruthi BS, Priya KL, Kesika P, Chaiyasut C. Evaluation of bioactivities of Morinda tinctoria leaves extract for pharmacological applications. Evaluation. 2018;11(2):100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sreena KP, Poongothai A, Soundariya SV, Srirekha G, Santhi R, Annapoorani S. Evaluation of in vitro free radical scavenging efficacy of different organic extracts of Morinda tinctoria leaves. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2011;3(Suppl 3):207–209. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian M, Balakrishnan S, Chinnaiyan SK, Sekar VK, Chandu AN. Hepatoprotective effect of leaves of Morinda tinctoria Roxb. against paracetamol induced liver damage in rats. Drug Invent Today. 2013;5(3):223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.dit.2013.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taranalli AD, Tipare SV, Kumar S, Torgal SS. Wound healing activity of Oxalis corniculata whole plant extract in rats. Ind J Pharma Sci. 2004;66(4):444. [Google Scholar]

- Ugur A, Sarac N, Ceylan O, Duru ME, Beyatli Y. Chemical composition of endemic Scorzonera sandrasica and studies on the antimicrobial activity against multiresistant bacteria. J Med Food. 2010;13(3):635–639. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]