Abstract

Purpose

To elicit patient preferences for social media utilization and content in the infertility clinic.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey study conducted in three US fertility practices. Women presenting to the infertility clinic for an initial or return visit were offered an anonymous voluntary social media survey. The survey elicited patient perception of whether social media use in the infertility clinic is beneficial, and preferences regarding topics of interest.

Results

A total of 244 surveys were collected during the study period, of which 54.5% were complete. Instagram is a more popular platform than Twitter across all age groups. Use of both platforms varies by age, with patients ≥ 40 less likely to be active users. The majority of respondents felt that social media provided benefit to the patient experience in the infertility clinic (79.9%). “Education regarding infertility testing and treatment” and “Myths and Facts about infertility” were the most popular topics for potential posts, with 93.4 and 92.0% of patients endorsing interest respectively. The least popular topic was “Newborn photos and birth announcements,” with only 47.4% endorsing interest. A little over half of respondents (56.3%) would feel comfortable with the clinic posting a picture of their infant. The vast majority of patients (96.2%) feel comfortable communicating electronically with their infertility clinic.

Conclusion

Patients are interested in the use of social media as a forum for patient education and support in the infertility clinic. Patient preferences regarding post topics should be carefully considered.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-018-1189-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Social media, Internet, Patient outreach, Infertility, In vitro fertilization

Introduction

The rise of social media over the past decade has been meteoric. Since its inception in 2004, Facebook has garnered two billion users worldwide [1]. As of 2016, 79% of US internet users also use Facebook [2]. Of Facebook users, 76% visit the site at least once per day and the average person spends 50 min per day on social media platforms [3]. Currently, over 80% of social media site visits occur on mobile devices. In 2013, smartphone owners averaged 13.8 mobile Facebook sessions daily [1]. Other platforms such as Instagram and Twitter have fewer users (32 and 24% of internet users respectively), but are more popular with a younger, highly educated demographic [2]. Social media now has the ability to impact every industry, including healthcare. As of 2012, 72% of adult internet users had searched for health information online in the past year [2]. Of smartphone users, 52% look up health issues on their phones, and 19% have downloaded apps to track or manage their health [2].

This phenomenon is likely more pronounced for infertility patients. Reproductive-aged women are large consumers of social media. Of internet users, 83% of women use Facebook compared with 75% of men. This gender difference is more pronounced with Instagram, with 38% of women active on this platform compared with 26% of men [2]. A recent qualitative study from Australia used data from focus groups that included couples desiring children in the future and couples actively trying to conceive. Participants cited the internet and social media as common sources of fertility-related information. However, actual knowledge regarding fertility in this cohort was low, indicating current gaps in access to accurate information [4]. Interestingly, reproductive endocrinologists are also using social media as an educational platform. Forums with colleagues allow physicians to “crowdsource” solutions to difficult cases [5].

Our patients are already using the internet and social media platforms as sources of support when struggling with infertility or recurrent miscarriage.

Today, a google search for “infertility support” yields over 22 million links [6]. Studies have demonstrated that the internet may be the only outlet for talking about infertility for some patients [7]. Given this, it is logical that the internet is also highly influential when patients are choosing a fertility clinic. A survey of SART clinics in 2011 showed that the majority had websites (96%), but only 30% were active on social media platforms [8]. This percentage is undoubtedly higher in 2017, but many clinics may still be missing opportunities to engage with current and potential patients in this forum or are still working to customize content [9]. While literature on the topic of social media has increased dramatically, there remains scant guidance for infertility clinics on what patients would like to see posted. Our objective was to survey patients visiting infertility practices, which varied in geography and practice model, and elicit their opinions regarding social media use and content.

Materials and methods

This was a survey study conducted at three infertility practices in the USA: The Fertility and Reproductive Medicine Center at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri (WU); Seattle Reproductive Medicine in Seattle, Washington (SRM); and Reproductive Medicine Associates of New Jersey in Basking Ridge, New Jersey (RMANJ). These practices were selected to provide variations in region, practice setting, and volume. Details regarding each practice, including social media posting frequencies, are presented in Table 1. All three practices post on social media platforms at least three times per week. All female patients were offered the voluntary anonymous survey upon checking in for an appointment and returned the completed surveys to the front desk. The survey was developed by the research team and included questions regarding current social media use, topics of interest for infertility clinic posts, and limited demographic and medical information. For each potential topic of interest, respondents were asked whether it was of interest to them (Y/N) and then asked to rank the topics in order of interest. The survey is not validated or correlated with other published studies. Surveys were collected for various time periods at each clinic during 2016. The pilot survey used at WU contained fewer demographic questions. The complete survey tool used at RMANJ and SRM is available in Appendix A. The survey results presented are unadjusted, meaning that imputation was not used to assign values for missing data. Results regarding survey responses were calculated based on the proportion of participants who provided a response to each question. Chi-square testing was used to compare categorical variables. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was considered exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University.

Table 1.

Practices included in social media survey study

| Practice name | Location | Practice model | State insurance mandate | Social media posting frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertility and Reproductive Medicine Center at Washington University | St. Louis, MO | Academic | No | Facebook—weekly Instagram—3×/week Twitter—rarely |

| Reproductive Medicine Associates of New Jersey | Basking Ridge, NJ | Academic affiliated private practice | Yes | Facebook—daily Instagram—rarely Twitter—daily |

| Seattle Reproductive Medicine | Seattle, WA | Private | No | Facebook—daily Instagram—2×/week Twitter—daily |

Results

A total of 244 surveys were collected during the study period. Of these, 133 (54.5%) were fully completed. RMANJ contributed the majority of surveys with 151 (61.9%), SRM contributed 53 (21.7%), and 40 (16.4%) came from WU. The demographics of the study cohort are presented in Table 2. The majority of patients were in their thirties, had undergone prior infertility treatment, and were well educated with household incomes exceeding $125,000 per year.

Table 2.

Demographics of study participants

| Parameter | Respondents (N) | Value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 177 | 34.8 |

| < 30 | 19 (10.7) | |

| 30–34 | 74 (41.8) | |

| 35–39 | 52 (29.4) | |

| ≥ 40 | 32 (18.1) | |

| Currently have children | 188 | 54 (28.7) |

| Prior infertility treatment | 223 | 131 (58.7) |

| Prior IVF | 227 | 63 (27.8) |

| Two or more miscarriages | 223 | 36 (16.1) |

| Education | 185 | |

| Less than 12th grade | 1 (0.05) | |

| High school diploma or GED | 6 (3.2) | |

| Some college | 22 (11.9) | |

| College degree | 61 (33.0) | |

| Graduate school | 95 (51.3) | |

| Household income | 166 | |

| < 24K | 0 (0.0) | |

| 25–74K | 24 (14.5) | |

| 75–124K | 51 (30.7) | |

| 125–199K | 60 (36.1) | |

| ≥ 200K | 31 (18.7) |

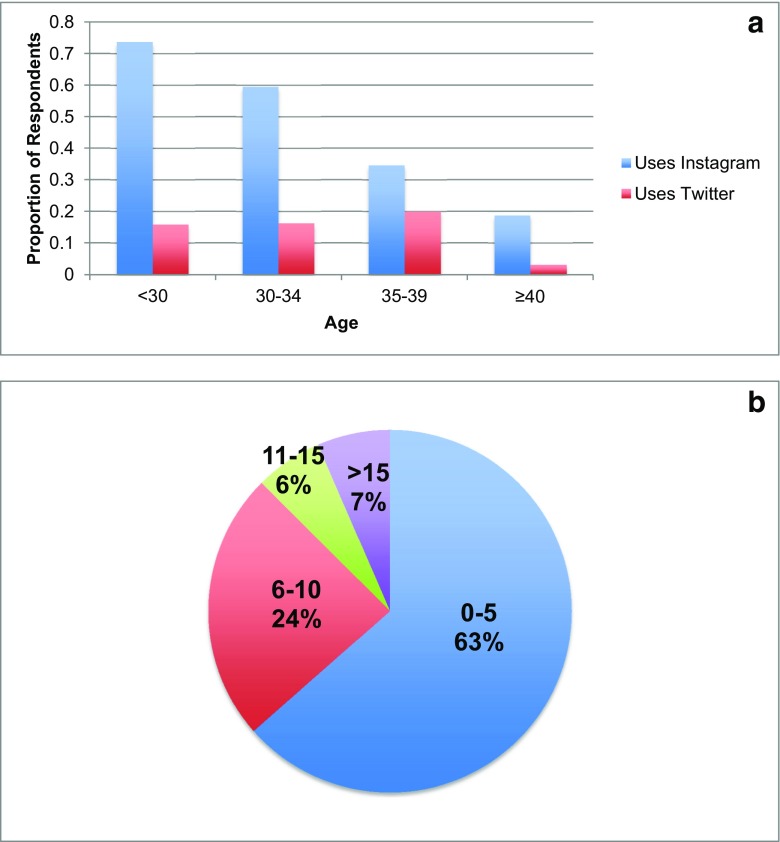

See Fig. 1 for the patterns of social media use among respondents. While Twitter use was fairly low across age groups, it was significantly less likely to be used by patients 40 and older (3.1 v. 17.9%, p = 0.035) (Fig. 1a). Instagram usage varied widely by age, with 62.3% of patients 34 and younger endorsing use, compared to 30% of patients 35 and older (p < 0.005) (Fig. 1a). We did not ask a binary question about Facebook use, we assumed almost universal use in this demographic. We elicited Facebook usage patterns by asking for number of times Facebook was accessed daily. Only 12.5% of patients reported accessing their Facebook feed more than 10 times daily, and this was not significantly different between age groups (Fig. 1b). Of 183 respondents, 96.2% feel comfortable communicating electronically with their clinic and only 7.7% have privacy concerns that prevent them from sending electronic communication to their fertility doctor.

Fig. 1.

Social media use in infertility patients. a Distribution of Instagram and Twitter users, stratified by age. b Average number of scrolls through Facebook timeline daily

Of 219 respondents, 79.9% felt that social media provides benefit to the patient experience in the infertility clinic. There was a trend toward younger patients perceiving more of a benefit, 82% of patients 34 and younger replied in the affirmative compared with 70% of patients 35 and older (p = 0.07). Belief in a social media benefit did not vary with education or income level.

Data addressing interest in possible post topics is presented in Table 3. “Education regarding infertility testing and treatment” and “myths and facts about infertility” were the most popular topics, with over 90% of patients endorsing interest. Other popular topics that were of interest to at least 80% of respondents included “managing stress: relaxation techniques,” “research studies taking place in infertility,” “patient success stories,” and “waiting on the results of the pregnancy test and coping tips.” “Newborn pictures and birth announcements” were the least popular topic, with only 47.4% endorsing interest and an average rank of 9.05 among the 11 topics. Patients with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) were not less likely to be interested in newborn photos than those without this history (45.4%, p = 0.91). Patients who currently have children were less likely to be interested in newborn photos than those without (33.3 v. 46.4%), but this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.11). We asked if respondents would be comfortable with their clinic posting a picture of their infant, and 56.3% replied in the affirmative.

Table 3.

Possible post topics ranked in order of patient interest

| Rank order | Topic | Average rank | Interested in topic (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Education regarding fertility testing and treatment | 2.27 | 93.4 |

| 2 | Managing stress: relaxation techniques | 4.43 | 84.0 |

| 3 | “Myths and Facts” about infertility | 4.74 | 92.0 |

| 4 | Research studies taking place in infertility | 4.88 | 88.2 |

| 5 | Waiting on the results of pregnancy test and coping tips | 5.23 | 80.0 |

| 6 | Patient success stories | 5.44 | 83.4 |

| 7 | Tips for talking about infertility with friends and family | 6.05 | 71.8 |

| 8 | Support group and meeting information | 6.61 | 55.8 |

| 9 | Meet the staff posts and photos | 6.70 | 77.8 |

| 10 | You and your partner: when couples disagree | 7.21 | 56.0 |

| 11 | Newborn pictures and birth announcement of our patients | 9.05 | 47.4 |

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the majority of infertility clinic patients feel that social media can provide an additional benefit to them. Patients are most interested in social media as a forum for education by their fertility clinic, as evidenced by the most popular post topics. Our data also indicate that patients are primarily interested in online resources for dealing with the emotional impact of infertility. Posts about relaxation techniques and managing the time prior to the pregnancy test were more popular, whereas information regarding local support group meetings was less popular (55.8%). Interestingly, while posts with newborn pictures or birth announcements often seemed to be the most “liked” on clinic social media sites, our survey indicates that fewer than half of patients want to see these posts and this topic was of the least interest to patients of all those presented. Seemingly in conflict with this, “patient success stories” were of interest to 83.4% of patients and ranked 6th of 11 topics. It is possible that patients are interested in hearing about other journeys through infertility, but that seeing newborn photos in isolation may be triggering. We predicted that patients with RPL would be less likely to be interested in newborn photos, but this was not the case. We also suspected that women with current children might be more interested, but again the data did not reflect this.

Consumer social media use and preferences have been studied extensively in marketing, but this is the first study to directly investigate this question in an infertile population. The varied geography and practice setting of the clinic respondents improves the generalizability of the study findings. While the high education level and income of survey participants is clearly not representative of all reproductive-aged women, it likely reflects the population seeking infertility care across the country.

Our study had several limitations. Given the novelty of this research topic, there was not a validated survey tool available. We were confronted with missing data as only a little over half of participants answered every question. If a question was left blank, the respondent was not included in the denominator. This approach to missing data assumes that nonresponse occurs randomly, and if this assumption is false can affect statistical validity. However, the decision to not impute missing data minimizes assumptions regarding survey responses. Survey nonresponse can be limited with electronic platforms that allow the design of mandatory questions. We chose to administer paper surveys for ease of distribution in the waiting room, but future investigations should consider a platform that would minimize missing data. The survey was optional for all patients checking in, and this likely introduced selection bias. Patients that use social media frequently may have been more interested in taking the survey, which could have influenced study results. We did not record the number of patients who declined the survey, leaving us unable to report response rate. The survey did not elicit whether participants were new or returning patients, and because it was anonymous we were unable to abstract this data. We were unable to explore if responses differed between academic and private centers because the academic center used a slightly different survey tool and contributed a small proportion of the total surveys (16.4%). Lastly, we assumed that a large majority of our respondents were Facebook users and thus did not elicit this information, which leaves us unable to directly compare utilization rates between platforms.

For infertility clinics that are interested in launching or expanding a social media presence, this study is encouraging and can provide some posting guidance. Our data suggest that social media efforts are best focused on Facebook and Instagram. Facebook is a great platform for sharing fertility news, trusted resources, and robust original content. Instagram can be used by clinics that choose to share infant photos, and is useful for any aspect of practice that is amenable to a picture or short video. These two platforms can be linked, facilitating easy administration. Maintaining an active social media presence requires frequent posting, the three practices included in this study vary in posting patterns but all post multiple times per week.

Our results indicate that most patients feel very comfortable communicating with their clinic electronically, with less than 10% endorsing privacy concerns. Not surprisingly, younger patients are more likely to use platforms other than Facebook, with over 60% of patients less than 35 using Instagram. Investing in development of multiple social media platforms may be beneficial in the long-term. Clinics should keep in mind that social media may already be an important part of a patient’s infertility journey. It may provide a source of support and advice from other women in similar circumstances but may also be a source of distress, with frequent pregnancy and birth announcements in their demographic. This study suggests that the primary goal of social media in the infertility clinic should be to inform current and potential patients and provide resources for education and support.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 32 kb)

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-018-1189-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Darcy E. Broughton, Phone: 360-271-4308, Email: d.broughtond@wustl.edu

Allison Schelble, Email: allison.schelble@wustl.edu.

Kristina Cipolla, Email: kcipolla@wustl.edu.

Michele Cho, Email: Michele.Cho@integramed.com.

Jason Franasiak, Email: jfranasiak@rmanj.com.

Kenan R. Omurtag, Email: omurtagk@wustl.edu

References

- 1.Most famous social network sites worldwide as of August 2017, ranked by number of active users. . 2017. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/. Accessed 30 Aug 2017.

- 2.Center PR. Social media update 2016 2016 http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/11/11/social-media-update-2016/. Accessed 30 Aug 2017.

- 3.Stewart JB. Facebook has 50 minutes of your time each day. It wants more. New York Times, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/06/business/facebook-bends-the-rules-of-audience-engagement-to-its-advantage.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

- 4.Hammarberg K, Zosel R, Comoy C, Robertson S, Holden C, Deeks M, Johnson L. Fertility-related knowledge and information-seeking behaviour among people of reproductive age: a qualitative study. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2017;20(2):88–95. doi: 10.1080/14647273.2016.1245447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franasiak JM, Ku LT, Barnhart KT, Online N, Communications C Curbside consultations in the era of social media connectivity and the creation of the Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Forum. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(4):885–886. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Google search for “infertility support” 2017. https://www.google.com/search?source=hp&q=infertility+support&oq=infertility+support&gs_l=psy-ab.3..0l4.996.3728.0.4077.20.19.0.0.0.0.123.1340.15j3.18.0....0...1.1.64.psy-ab..2.18.1337.0..0i131k1.8IRgjAi70dk. Accessed 30 Aug 2017.

- 7.Epstein YM, Rosenberg HS, Grant TV, Hemenway BAN. Use of the internet as the only outlet for talking about infertility. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(3):507–514. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omurtag K, Jimenez PT, Ratts V, Odem R, Cooper AR. The ART of social networking: how SART member clinics are connecting with patients online. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omurtag K, Turek P. Incorporating social media into practice: a blueprint for reproductive health providers. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56(3):463–470. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182988cec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 32 kb)