Abstract

Background

Cancer is a leading cause of death among United States (US) adults. Only 54% of US adults reported seeking cancer information in 2014. Cancer information seeking has been positively associated with cancer-related health outcomes such as screening adherence.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of studies that used data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) in order to examine cancer information seeking in depth and the relationship between cancer information seeking and cancer-related health outcomes. We searched five databases and the HINTS website.

Results

The search yielded a total of 274 article titles. After review of 114 de-duplicated titles, 66 abstracts, and 50 articles, 22 studies met inclusion criteria. Cancer information seeking was the outcome in only four studies. The other 18 studies focused on a cancer-related health outcome. Cancer beliefs, health knowledge, and information seeking experience were positive predictors of cancer information seeking. Cancer-related awareness, knowledge, beliefs, preventive behaviors, and screening adherence were higher among cancer information seekers.

Conclusions

Results from this review can inform other research study designs and primary data collection focused on specific cancer sites or aimed at populations not represented or underrepresented in the HINTS data (e.g., minority populations, those with lower socioeconomic status).

Keywords: HINTS, cancer information seeking, scoping review, cancer outcomes

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death among adults in the United States (US) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics, 2015). Despite the high likelihood of either being diagnosed with or otherwise affected by cancer at some point in their lives, many US adults have never looked for information about cancer (National Cancer Institute, 2010). Among cancer information seekers in the US, the Internet was the most commonly used source of information about cancer followed by health care providers (National Cancer Institute, 2010). In fact, more than half of US adults who have ever looked for cancer information reported that the Internet was where they went first during their most recent search for information about cancer (National Cancer Institute, 2010). While online cancer information seeking is highly prevalent among US adults (National Cancer Institute, 2010), disparities in Internet use persist among minority, older, and lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups (Pew Research Center, 2013).

The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) is a population-based survey that has been conducted in the US and Puerto Rico (National Cancer Institute, n.d.). Many researchers have used HINTS data to examine cancer communication (e.g., cancer information seeking) and cancer-related health outcomes (e.g., screening adherence)(Hamilton, Breen, Klabunde, Moser, Leyva, Breslau, & Kobrin, 2015). Our scoping review provides details about how the HINTS questions have been used to examine cancer information seeking. This information would be useful not only to cancer prevention and control researchers interested in using HINTS data, but also those cancer prevention and control researchers who may be interested in modifying the wording of HINTS questions for specific cancer sites. For example, some of the studies used the HINTS mental modules for specific sites such as colorectal, lung, and skin cancer (Hay 2015; Han 2009; Hay 2009; Zhao 2009).

A scoping review “provides a preliminary assessment of the potential size and scope of available research literature. It aims to identify the nature and extent of research evidence.” (Grant and Booth, 2009, p31). This scoping review aimed to summarize and disseminate knowledge about how researchers have used HINTS questions to examine cancer information seeking among US and Puerto Rican adults. Seminal scoping methodology studies (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac, Colquhoun, O’Brien, 2010) and comprehensive scoping reviews published in the past five years informed our approach for this review (Friedman et al, 2015; Renton et al, 2014).

METHODS

Arskey and O’Malley’s (2005) methodological framework for conducting scoping studies involves: (1) identifying the research question; (2) searching for relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The process may also involve consulting with relevant stakeholders to inform or validate study findings. The first four stages are described in this section. Stage five is described in the Results section.

Stage 1 – Identifying the research question

It has been suggested that health information seeking, whether it be online or offline, may have a positive impact on behavioral changes that will lead to improved health outcomes, thereby reducing health disparities (David & Case, 2012). We conducted this scoping review to answer the following five research questions (RQ) about cancer information seeking:

RQ1: Where have researchers published their findings about cancer information seeking?

RQ2: How have researchers operationalized cancer information seeking?

RQ3: Which subpopulations of adults in the US and Puerto Rico have researchers used the HINTS data to examine cancer information seeking?

RQ4: Which modifiable factors have been identified as predictors of cancer information seeking?

RQ5: Which cancer-related health outcomes were positively associated with cancer information seeking?

Stage 2 – Search for relevant studies

The primary author (LTW) searched five major databases: CINAHL Complete (n=23 abstracts located), PubMed (n=64 abstracts), Social Sciences Citation Index of the Web of Science Core Collection (n=64), Communication Abstracts (n=30); and Communication and Mass Media Complete (n=36). These online databases were searched using the following search terms and Boolean operators: ((("Health Information National Trends Survey") AND cancer AND information) AND seek*). “Looking” and “searching” were identified during our scoping review process as alternative words to describe “seeking” and were subsequently added to our search term strategy. We repeated the search in all databases using the following search term: ((("Health Information National Trends Survey") AND cancer AND information) AND (seek* OR look* OR search*)). We also searched the HINTS website (http://hints.cancer.gov/research.aspx) for additional studies that we may have missed in the database search.

Stage 3 – Selecting studies

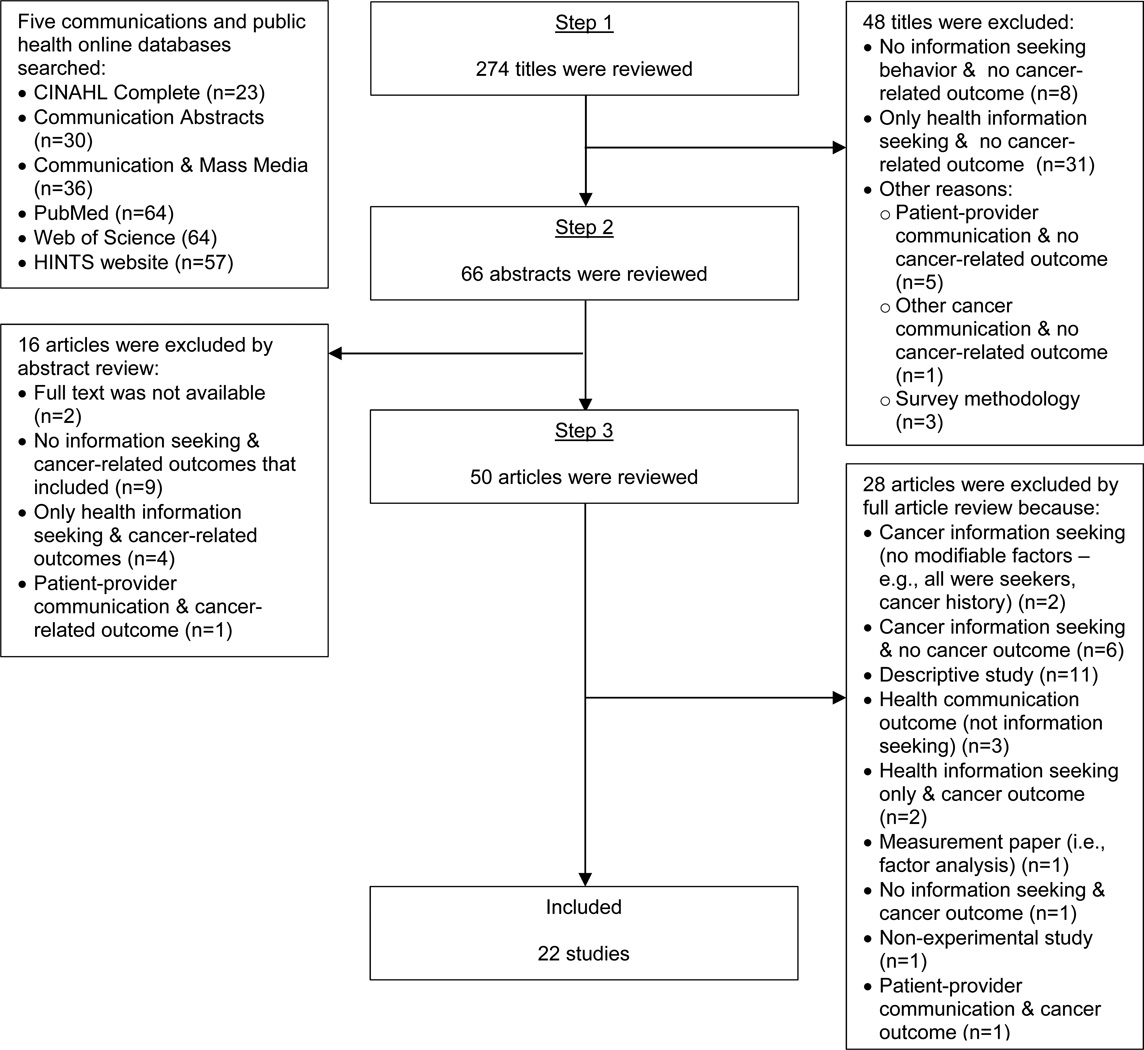

Our study selection process (Figure 1) involved three steps: (1) 274 title reviews, (2) 66 abstract reviews, and (3) 50 full article reviews. Titles that did not focus on information seeking or a cancer-related outcome, or only focused on health information seeking were excluded from subsequent abstract and full text review. All titles that were suggestive of information seeking or a cancer-related health outcome were reviewed. Full articles were reviewed for abstracts that focused on cancer or health information seeking and a cancer-related health outcome.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of scoping review process.

Only articles published in scientific journals were included. Journal articles that were not written in English language were excluded. Only empirical research studies that examined predictors of cancer information seeking or the association between cancer information seeking and a cancer-related health outcome were included. Thus, non-experimental and descriptive studies were excluded. Online cancer information seeking was a secondary outcome of interest of this scoping review in an effort to further our understanding of the progress toward the Healthy People 2020 Health Communication and Health Information Technology objective of improving access to online health information (Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

Stage 4 – Charting the data

Two authors (LTW and DBF) developed and pilot tested an abstraction tool using Google Forms. The online abstraction tool, based on previous scoping review tools (e.g., Friedman et al., 2015), contained 53 items that included multiple-choice items, check boxes, and open-ended short and paragraph questions. After the first author conducted the initial full text abstraction, a 10% random sample of articles were reviewed by a co-author (DBF) as a quality control check. All data were entered using the Google Form, which was exported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

RESULTS

Stage 5 - Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The last stage of Arskey and O’Malley’s (2005) six-stage methodological framework that we used for this scoping review is the collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. Below we describe the selection and overview of included studies. The rest of our results also are reported for each of our research question.

Selection and overview of included studies

After the article review, 28 of 50 studies were excluded. Figure 1 presents the scoping review process and reasons for the inclusion and exclusion of articles. A total of 22 studies were included in this review. Only four studies examined modifiable factors (e.g., cancer beliefs, health knowledge, and information seeking experience) that could impact cancer information seeking behavior. This includes one study that focused on information overload among cancer information seekers. Most (n=18) of the included studies examined the relationship between cancer information seeking and a cancer-related health outcome. Cancer site specific health outcomes included leading causes of cancer death such as colorectal cancer (n=4) (Hay 2015; Chen 2014; Hay 2006; Ling 2006). Gender-specific cancer sites included breast (n=1) (Madadi 2014), cervical (n=1) (Kontos 2012), and prostate (n=1) (Finney-Rutten 2005) cancer. Skin cancer health outcomes were also examined (n=1) (Hay 2009). Two studies looked at multiple cancer sites (i.e., colorectal, lung, skin, and prostate) (Han 2009; McQueen 2008). Several studies examined general cancer-related health outcomes such as awareness about genetic testing, health knowledge, perceptions of cancer risk and other cancer beliefs, smoking cessation, and preventive behaviors such as eating five or more servings of fruits and vegetables daily.

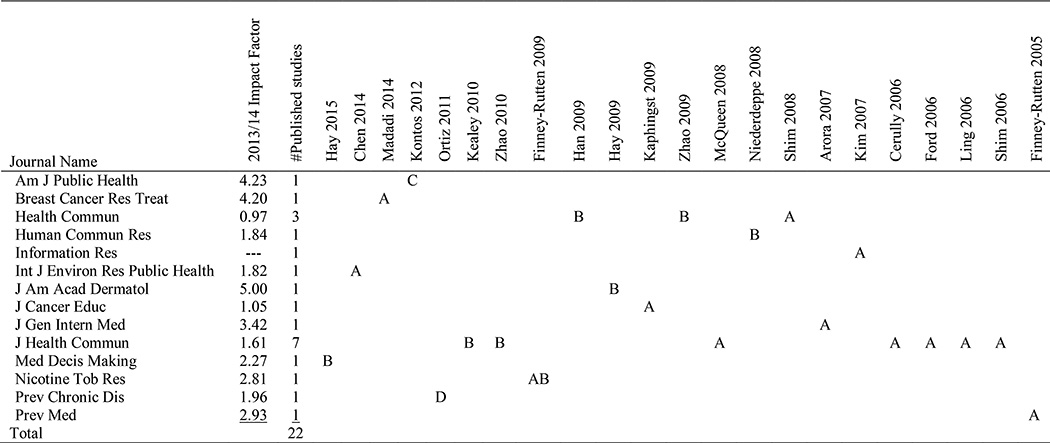

RQ1: Where have researchers published their study findings about cancer information seeking?

Studies were published in 14 scientific journals across the fields of communications, medicine, and public health. More than half (n=12) of the included studies were published in health communication journals such as the Journal of Health Communication and Health Communication. Researchers also published findings in high impact medical (e.g., Breast Cancer Research and Treatment), and public health (e.g., American Journal of Public Health) journals. The HINTS 1 (2003) data was used in most (n=12) studies. It is important to note that two studies using the HINTS 1 (2003) (Madadi 2014) and HINTS 2 (2005) (Hay 2015) a decade or more since these data were collected. Only one study used each of the more recent datasets – HINTS 3 (2007) (Kontos 2012) and HINTS Puerto Rico (2009) (Ortiz 2011). (Table 1) None of the included studies used data from the fourth iteration (Cycles 1–4) of the HINTS.

Table 1.

Distribution of included studies (n=22) by journal and HINTS iteration

Notes: 2013/2014 Impact Factor; A-HINTS 1 (2003); B-HINTS 2 (2005); C-HINTS 3 (2007); D-HINTS Puerto Rico (2009)

RQ2: How have researchers operationalized cancer information seeking?

Most of the included studies (n=12) operationalized cancer information seeking as, Have you ever looked for information about cancer from any source? (yes/no) (Kontos 2012, Ortiz 2011, Keally 2010, Zhao 2010, Han 2009, Kaphingst 2009, Zhao 2009, McQueen 2008; Cerully 2006, Ford 2006; Ling 2006). Shim (2006) defined cancer information seeking in the context of having done so within the past year. Two researchers specifically focused on non-seekers (Hay 2015; Ford 2006). Several researchers also looked at surrogate seekers (i.e., having others look for information about cancer on one’s behalf (n=4) (Zhao 2010; McQueen 2008; Arora 2008; Ling 2006). Other cancer information seeking constructs such as barriers encountered during the search process, self-efficacy to conduct future searches, and combinations of seeking with scanning (i.e., paying attention to health information on various media sources) were also used and are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operationalization of cancer information seeking

| Outcome | Question & Response Options | First Author (Year) | HINTS 1 (2003) |

HINTS 2 (2005) |

HINTS 3 (2007) |

HINTS PR (2009) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Information Seeking |

Have you ever looked for information about cancer from any source? (yes/no) |

Madadi M (2014) | √ | |||

| Kontos EZ (2012) | √ | |||||

| Ortiz (2011) | √ | |||||

| Kealy E (2010) | √ | |||||

| Zhao X (2010) | √ | |||||

| Han (2009) | √ | |||||

| Kaphingst KA (2009) | √ | √ | ||||

| Zhao X (2009) | √ | |||||

| McQueen (2008) | √ | |||||

| Cerully (2006) | √ | |||||

| Ling BS (2006) | √ | |||||

| Ford JS (2006) | ||||||

| Cancer Information Seeking (Past Year) |

Have you looked for information about cancer from any source? (yes/no) and About how long ago was that? (open-ended responses] for days, weeks, months, or years ago) were combined to create a new variable.

|

Shim M (2006) | √ | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking (Past Week) |

Have you looked for information about cancer from any source? (yes/no) and About how long ago was that? (open-ended responses] for days, weeks, months, or years ago) were combined to create a new variable.

|

Niederdeppe (2008) | √ | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking (Surrogate Seekers) |

Excluding your doctor or health care provider, has someone else ever looked for information about cancer for you? (yes/no) |

Zhao X (2010) | √ | |||

| McQueen (2008) | √ | |||||

| Ling BS (2006) | √ | |||||

| Cancer Information Seekers, Surrogate Seekers, and Non- seekers (4 Groups) |

Cancer information seeking and surrogate seeking questions were combined to create four groups: seekers only; seekers and surrogate seekers; surrogate seekers only, non-seekers. (Seekers=seeker/seeker & surrogate seeker; Non-seekers=surrogate seeker & non-seeker). |

Arora NK (2008) | √ | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking (Online) |

Cancer/Health Information seeking on the Internet (authors don’t adequately explain how they derived this measure) |

Finney-Rutten (2009) | √ | √ | ||

| Have you ever visited an Internet web site to learn specifically about cancer? (yes/no) |

Hay JL (2009) | √ | ||||

| Ever looked for information about cancer…source=Internet (Internet/Other) |

Chen (2014) | √ | ||||

| Ever looked for information about cancer…source =Internet (Internet seeker/Non- Internet seeker/Non-seeker) |

Kontos (2012) | √ | ||||

| Respondents’ Internet use for cancer-specific information in the past 12 months was assessed: 1 (did not use the Internet to look for health or medial information), 2 (used the Internet for cancer-unspecific health information), 3 (used the Internet for cancer-specific information); M = 2.02, SD = .81. |

Shim M (2008) | √ | ||||

| Skin Cancer Information Seeking (Online) |

Looked for information on the Internet about protecting themselves from the sun (in the past 12 months) (yes/no) |

Hay JL (2009) | √ | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking Experiences |

Based on the results of your most recent search for information on cancer, how much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements:

versus disagree/strongly disagree |

Zhao X (2010) | √ | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking Experience (ISEE) Scale |

Based on the results of your most recent search for information on cancer, how much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements:

|

Chen (2014) | √ | |||

| Arora (2007) | √ | |||||

| Kim (2007) | √ | |||||

| Cancer Information Overload |

There are so many different recommendations about preventing cancer it’s hard to know which ones to follow. (Agree/Disagree) |

Kealy (2010) | √ | √ | ||

| Kim (2007) | ||||||

| Cancer Information Seeking Self-Efficacy |

Overall, how confident are you that you could get advice or information about cancer if you needed it? |

Hay JL (2015) | √ | |||

| Chen (2014) | √ | |||||

| HINTS 2003: 4-point Likert scale was used (very confident/somewhat confident/slightly confident/not confident at all HINTS 2005 and beyond: 5-point Likert scale: 1=completely confident/5=not confident at all) |

||||||

| • Dichotomized: completely/very confident versus somewhat/a little/not confident) |

Zhao X (2010) | √ | ||||

| • Reverse coded: 5=completely confident to 1=not confident at all) |

Zhao X (2009) | √ | ||||

| Cancer/Health Information-Seeking (Summary Score) |

The following questions were used to calculate a summary score:

|

Hay JL (2015) | √ | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking/Paying Attention to Media Sources |

Paying attention to media sources (TV, radio, newspapers, magazines, Internet) AND ever looked for information about cancer (1-pay attention a little/not at all OR no seek; 2=pay attention a lot/some OR seek (range: 6–12) |

Finney-Rutten (2005) | √ | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking * Scanning |

Pay attention and seeking variables were combined to create a typology of cancer information scanning and seeking behavior (SBB). The categories of SSB are: ‘low- scan=no seekers, low-scan=seekers, high-scan=no seekers, high-scan=seekers. |

Shim M (2006) | √ | |||

A secondary focus of our study was to examine online cancer information seeking (6 studies), which one study did by assessing participants’ yes/no responses to whether or not they use the Internet to look for information about cancer (Hay 2009). Hay and colleagues (2009) also asked about sun-protection specific cancer information seeking because the skin cancer mental module included the following yes/no question, In the past 12 months, have you looked for information on the Internet about protecting yourself from the sun? Two studies assessed online cancer information seeking by assessing whether or not cancer information seekers used the Internet during their most recent search for information about cancer (Chen 2014; Kontos 2012). Shim and colleagues (2008) combined the online health/cancer information seeking questions to create a new variable. Finney-Rutten and colleagues (2005) also combined the online health/cancer information seeking questions, but did not provide details about how they constructed the new variable reported in their data table.

Few studies (n=5) explicitly stated that their work was informed by a conceptual model or theoretical framework. The theories or frameworks presented were: Knowledge Gap Hypothesis (Shim 2008); National Center for Research on Evaluation Standards and Student Testing Model of Problem Solving (Kim 2007); National Trends Survey Framework (Kim 2007); Precaution Adoption Process Model (Kim 2007); Precede-Proceed Model (Chen 2014); Risk Perception Attitude (RPA) Framework (Zhao 2009); and Structural Influence Model of Communication Inequalities (Kontos 2012).

RQ3: Which subpopulations of adults in the United States and Puerto Rico have researchers used the HINTS data to examine cancer information seeking?

Population characteristics of all 22 studies are described in Table 3. Only six included studies used the full HINTS sample, which was representative of US and Puerto Rican adults. The HINTS Puerto Rico (2009) data was not subsampled. Most of the included studies (n=13) used subpopulations of the HINTS sample. These subpopulations included adults 45+ years old, females >40 years old, online adults, smokers, and adults who reported consuming less than five servings of fruits and vegetables daily (Finney-Rutten 2005, Ford 2006, Ling 2006, McQueen 2008, Chen 2014, Madadi 2014, Shim 2008, Zhao 2009, Finney-Rutten 2009, Cerully 2006). It is important to note that Finney-Rutten and colleagues (2009) combined HINTS 1 (2003) and HINTS 2 (2005) data which yielded a larger sample of smokers (n=2,257) in comparison to the 340 smokers that Zhao and colleagues (2009) used for their study with HINTS 2 (2005) data. Several studies used data from the colorectal, skin, and lung cancer mental modules (Han 2009, Hay 2009, Hay 2015). The lower age cutoffs for subpopulations used in studies that focused on a specific cancer site were informed by cancer screening guidelines and varied based on the researchers’ objectives. For example, Ford and colleagues (2009) included adults five years younger (i.e., 45+ years old) than the earliest age recommended for colorectal cancer screening. Other researchers used 50 years old as their age cutoff. All of the included studies excluded adults who had been diagnosed with cancer.

Table 3.

Population/sample characteristics, cancer information seeking behaviors, and cancer-related health outcomes

| First Author (Year) |

Population/ Subpopulation (Sample Size) |

Sample Characteristics | Cancer Information Seeking Behavioral & Psychosocial Factors |

Cancer-Related Health Outcomes & Theoretical Frameworks |

Cancer Type |

HINTS (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hay (2015) | Participants 18+ years old who completed the colorectal cancer mental module (1,789/1,937) 148=missing data |

Race/ethnicity: 7.8% Hispanic 11.6% Foreign born 20.3 ± 1.58 years in USa SES: 57.3% Some college+ 24.9% ≤$29K Cancer History: 10.3% family history of colorectal cancer |

Lower cancer/health information seeking summary score was positively associated with ambiguity about CRC risk perceptions. Self-efficacy (n.s). |

7.5% did not know their comparative CRC risk 8.7% did not know their absolute CRC risk |

CRC | HINTS 2 (2005) |

| Chen (2014) | 55+ year old adults (1,818) |

Race/ethnicity: 78% White 10% Hispanic SES: 56% Some college+ 58% ≤$35K Cancer History: 66% family history of cancer |

Online cancer information seeking was positively associated with CRC screening adherence. Seeking experiences (n.s.) Self-efficacy (n.s.) |

64% were compliant based on the following CRC screening guidelines:

|

CRC | HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Madadi (2014) | Adherent and non-adherent women >40 years old (2,370) |

Race/ethnicity: 77% White SES: 56% Some college+ 36% ≤$25,000/year 49% Employed Cancer History: 75% Family member had cancer |

The association between cancer information seeking and mammography attitudes/screening adherence was not statistically significant. |

70% adherent

were thinking about getting a mammogram |

Breast cancer |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Kontos (2012) | Online and offline cancer information seekers & non-seekers (7,674) |

Race/ethnicity: 65% NH White 12% Hispanic SES: 60% Some college+ 30% <$35,000/year Cancer History: Not reported |

Online cancer information seeking was positively associated with HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge, which was significantly higher compared to non-seekers. Offline vs. online (n.s.) |

70% heard of HPV vaccine 70% HPV was a STI 75% HPV cause cervical cancer (Note: Awareness/knowledge highest among online seekers) Structural Influence Model of Communication Inequalities |

Cervical cancer |

HINTS 3 (2007) |

| Ortiz (2011) | Puerto Rican adults (611) |

Race/ethnicity: Not reported SES: 44.5% College+d 40.2% Employed Cancer History: Not reported |

Cancer information seekers were more aware of genetic testing than non-seekers. |

55.8% had heard of direct-to- consumer genetic tests 4.3% reported ever having a genetic test. |

Genetic Testing |

HINTS PR (2009) |

| Kealey (2010) | US adults (5,586) |

Race/ethnicity: 76.9% White 9.3% Hispanic SES: 60.3% Some college+ 40.7% <$35,000/year Cancer History: Not reported |

Cancer information seekers experienced significantly less cancer information overload than non-seekers. Cancer information seeking was not significantly associated with cancer beliefs or risk perceptions. |

Cancer information overload (i.e., ambiguity about how to prevent cancer), beliefs about behavioral/lifestyle cancer risk factors, and perceptions of comparative risk of getting cancer were assessed. |

All cancers |

HINTS 2 (2005) |

| Zhao (2010) | US adults (5,586) |

Race/ethnicity: 69.9% White 13.0% Hispanic SES: 55.6% College+d 58.6% Employed Cancer History: 11.4% Had cancer |

Cancer information seeking/self-efficacy was inversely associated with having undesirable beliefs about cancer among Whites only. Surrogate seeking (n.s.) |

Undesirable cancer beliefs were compared between US and foreign born Whites and Hispanics:

|

All cancers |

HINTS 2 (2005) |

| Finney-Rutten (2009) | Smokers (2,257) |

Sociodemographics: 59.7% NH White 13.9% Hispanic SES: 41.8% College+ 38.9% <$25,000/year Cancer History: 11.4% Had cancer |

The relationship between online cancer/health information seeking and smoking status was not statistically significant. |

Cancer communication outcomes were assessed among moderate-heavy, light, and intermittent tobacco users. |

Lung cancer (smoking is also a risk factor for other types of cancer) |

HINTS 1 (2003) & HINTS 2 (2005) |

| Han (2009) | CRC (n=1,788), skin (n=1,594), and lung (n=1,777) cancer mental modules participants (5,159) |

Race/ethnicity: 79.9% White SES: 51.7% College+ Cancer History: Not reported |

Cancer information seeking was inversely associated with ambiguity about CRC prevention. Skin cancer (n.s.) Lung cancer (n.s.) |

Ambiguity about CRC, skin, and lung cancer prevention was assessed. |

CRC, skin, and lung cancer |

HINTS 2 (2005) |

| Hay (2009) | Skin cancer mental module participants (1,633) |

Race/ethnicity: 66.9% NH White 14.7% Hispanic SES: 52.6% College+ Cancer History: 9.9% Family member had skin cancer 5.1% Melanoma 4.8% Non-melanoma |

Skin cancer information seeking was a positively associated with some protective behaviors (i.e., using sunscreen, wearing sun-protective clothing). Skin cancer knowledge (n.s.) Skin cancer beliefs (n.s.) Staying in the shade (n.s.) |

Skin cancer knowledge, beliefs, and protective behaviors were assessed. Protective behaviors were:

|

Skin cancer |

HINTS 2 (2005) |

| Kaphingst (2009) | US adults (n=5,813) |

Race/ethnicity: 75% NH White SES: 60% <$50,000/year Cancer history: 13% Had cancer 65% Family member had cancer |

Positive beliefs about the relationship between knowing one’s family history/genes and cancer risk reduction was positively association with cancer information seeking. |

N/A – Cancer information seeking was the outcome of interest |

All cancers |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Zhao (2009) | Smokers who completed the lung cancer mental module (n=340) |

Race/ethnicity: Race/Ethnicity SES: Education Cancer history: Not reported (Descriptive statistics were not reported) |

Cancer information seeking was positively associated with absolute risk, the interaction of absolute* comparative risk, response self-efficacy about lung cancer, and self-efficacy. Comparative risk (n.s.) |

Lung cancer risk perceptions and response efficacy (i.e., not much one can do to lower their lung cancer risk) were assessed. Risk Perception Attitude (RPA) Framework |

Lung cancer (smoking is also a risk factor for other cancers) |

HINTS 2 (2005) |

| McQueen (2008) | 50+ year old adults (2,519) |

Race/ethnicity: 74.5% NH White 6.7% Hispanic SES: Not reported Cancer History: Not reported |

Cancer information seeking (including surrogate seeking) was not significantly associated with cancer beliefs (i.e., worry, risk perceptions). |

Cancer worry and risk perceptions were assessed. |

Breast, CRC, prostate cancer |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Niederdeppe 2008 | US adults (n=5,585) |

Race/ethnicity: Race/ethnicity were not reported SES: 57.5% Some college+ Cancer History: 11.3% Had cancer 71.5% Family member had cancer |

Health knowledge was positively associated with cancer information seeking. Interactions between cancer news events and education, health knowledge, and social networks were also positively associated with cancer information seeking. |

N/A – Cancer information seeking was the outcome of interest Knowledge Gap Theory |

Breast and lung cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

HINTS 2 (2005) |

| Shim (2008) | Online adults (3,982) |

Race/ethnicity: 76% NH White 8% Hispanic SES: 75% Some college+ Cancer History: 10% Had cancer 65% Family member had cancer |

Online cancer information seeking was positively associated with cancer knowledge. |

Cancer knowledge about preventive behaviors/lifestyle factors and screening was assessed. Knowledge Gap Theory |

All cancers |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Arora (2007) | Cancer information seekers, surrogate seekers, and non-seekers (6,369) |

Race/ethnicity: 71.8% NH White 11.7% Hispanic SES: 51.1% Some college+ 59.8% Employed Cancer History: 10.9% Had cancer 54.2% Family member had cancer |

Cancer information seeking experiences were positively associated with cancer beliefs. |

Cancer information seeking experiences and the following cancer beliefs were examined:

|

All cancers |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Kim (2007) | US adults (n=6,369) |

Race/ethnicity: 76.2% NH White 7.3% Hispanic SES: 29.9% Some college 24.7% <$25,000 60.7% Employed Cancer history: 5.3% had cancer 44.3% Family member had cancer Descriptive statistics reported for overloaded |

Health literacy was inversely associated with cancer information overload. However, seekers who were concerned about the quality of the information they found were more likely to feel overloaded. |

N/A – Cancer information overload was the outcome of interest National Center for Research on Evaluation Standards and Student Testing Model of Problem Solving National Trends Survey Framework Precaution Adoption Process Model |

All cancers |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Cerully (2006) | US adults who reported consuming <5 servings of fruits and vegetables daily (5,265) |

Descriptive statistics were not reported |

Nonlisters (i.e., did not list F/V consumption for self or others) were unexpectedly more likely to be seekers, but less likely to trust sources of cancer information as expected. |

Cancer communication, knowledge, and beliefs were examined among adults who consumed less than five servings of fruits and vegetables daily. |

All cancers |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Ford (2006) | 45+ year old adults (3,131) |

Race/ethnicity: 77.9% NH White 7.6% Hispanic SES: 47.6% Some college 31.2% <$25,000 Cancer history: 16.7% had cancer 67.3% Family member had cancer |

Non-seekers were less knowledgeable about CRC screening |

Knowledge of CRC screening recommendations was examined |

CRC | HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Ling (2006) | >50 years old adults (2,670) |

Race/ethnicity: 80.0% White Hispanic not reported SES: 28.1% Some college+ Income not reported Cancer History: Not reported |

Both seekers and those who had surrogate seekers were more likely to be up-to-date on CRC screening. |

CRC cancer screening adherence was assessed. |

CRC | HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Shim (2006) | US adults (n=6,369) |

Race/ethnicity: 70.3% White 12.7% Hispanic SES: 31.3% Some college+ Cancer History: 12.0% Had cancer 62.8% Family member had cancer |

Cancer prevention knowledge, lifestyle behaviors, and screening adherence were positively associated with cancer information seeking and scanning. However, knowledge was inversely associated with the interaction of seeking*scanning behaviors. |

N/A – Seeking and scanning behaviors were the outcomes of interest |

CRC, breast, and prostate |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

| Finney-Rutten (2005) | 50+ year old males (927) |

Race/ethnicity: 79.5% NH White 7.0% Hispanic SES: 27.8% ≤$25,000 49.6% Some college+ Cancer History: Not reported |

Attention/seeking was not associated with PSA testing |

PSA testing | Prostate cancer |

HINTS 1 (2003) |

Footnotes:

Mean ± Standard Error;

Mean ± Standard Deviation;

Includes cohabitating (or living with a partner);

Does not include vocational/technical training;

AOR=adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval; CRC=colorectal cancer; FOBT=fecal occult blood test; NH=non-Hispanic; NR=not reported; STI=sexually transmitted infection |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

RQ4: Which modifiable factors have been identified as positive predictors of cancer information seeking?

There were only four studies that examined cancer information seeking as an outcome (Kaphingst 2009; Niederdeppe 2008; Kim 2007; Shim 2006). This includes one study that examined cancer information overload (Kim 2007). Another study examined not only information scanning in addition to information seeking, but also the interaction between seeking and scanning which was used to create a typology of these two cancer communication behaviors (Shim 2006). Positive cancer beliefs and cancer information seeking experiences have been shown to be positively associated with cancer information seeking. However, included studies found that cancer information seeking self-efficacy was positively associated with cancer information seeking (Zhao 2009), and mean health knowledge score was negatively associated with the interaction between information seeking*scanning typology (Shim 2006). These results are described in Table 3.

RQ5: Which cancer-related health outcomes were positively associated with cancer information seeking?

This includes one study that focused on ambiguity about perceived colorectal, lung, and skin cancer risk (Han 2009). Most of the studies (n=5) focused on colorectal (Chen 2014, Ford 2006, Ling 2006), breast (Madadi 2014), or prostate screening adherence (Finney-Rutten 2005). One study focused preventive behaviors (i.e., sun-protection; n=1) (Hay 2009). Other studies examined on HPV awareness and knowledge (Kontos 2012), and colorectal (Hay 2015, McQueen 2008) or breast/prostate (McQueen 2008) cancer beliefs (Hay 2015). Several studies (n=7) examined cognitive, psychosocial, and preventive behaviors as cancer-related health outcomes including awareness and use of direct-to-consumer genetic tests (n=1) (Ortiz 2011); cancer knowledge (n=1) (Shim 2008); cancer beliefs (n=3) (Kealey 2010, Zhao 2010, Arora 2008), fruit and vegetable daily intake (Cerully 2006), and smoking cessation (Finney-Rutten 2009). These results are presented in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Cancer information seeking has been shown to be positively associated with cancer-related health outcomes (David and Case 2012, Shim 2006). Although some iterations of the HINTS survey are more focused on cancer information seeking, all versions of the survey that have been administered to date ask, Have you ever looked for information about cancer from any source? Although earlier HINTS iterations asked About how long ago was that? later HINTS iterations do not include this follow-up question. We believe it is helpful that some of the included studies were able to add a timeframe to cancer information seeking such as the past year (Shim 2006) or past week (Niederdeppe 2008). This additional variable was especially important for Niederdeppe and colleagues (2008) who examined associations between cancer information seeking and recent celebrity news events, especially considering short news cycles.

Earlier versions of HINTS also asked about surrogate cancer information seekers, that is Excluding your doctor or health care provider, has someone else ever looked for information about cancer for you? Although later HINTS iterations do assess whether or not participants have looked for information about health or medical topics for someone else, the concept of surrogate cancer information seeking seems to have been abandoned. Nonetheless, this review paper provides a comprehensive summary of how researchers have conceptualized cancer information seeking, including the creation of a group or typology to describe self-seekers, surrogate seekers only, self-seekers and surrogate seekers, and non-seekers (Arora 2008). It is important to note, however, that Arora and colleagues (2008) did not consider surrogate seekers to be cancer information seekers.

The HINTS assessment of online cancer information seeking has varied over the years. Earlier HINTS iterations asked specifically about using the Internet to find information about cancer, e.g., Have you ever visited an Internet web site to learn specifically about cancer? Later HINTS iterations have assessed online cancer information seeking in various ways, leaving some researchers to combine multiple questions as a proxy measure for assessing online cancer information seeking. Recent HINTS iterations have focused more on online health information seeking, which is one of our nation’s Healthy People 2020 goals (Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). The use of different questions to assess online cancer information seeking can become problematic for researchers who are interested in combining multiple years of HINTS data as Finney-Rutten (2009) did to yield a larger data sample for studying subpopulations smokers.

Research Gaps and Recommendations for Future Research

By summarizing the various ways that researchers have used HINTS to operationalize cancer information seeking, this scoping review can inform future research aimed at better understanding this multifaceted concept beyond a simple yes or no response. In addition, the potential limitation of recall bias introduced by asking survey participants about their most recent search could be addressed by giving focus group participants an opportunity to look for cancer information and then in real time ask them about their seeking experiences (Lambert and Loiselle 2008). This could enable researchers to obtain a more reliable measure of cancer information seeking which would likely increase our understanding of the relationship between communication and health-related outcomes. Future research should also involve adapting HINTS questions to ask about people’s search for information about specific cancer sites. As an example, several studies included in this review used the colorectal, lung, and skin cancer mental modules which asked questions about specific cancer types as opposed to cancer in general (Hay 2015; Han 2009; Hay 2009; Zhao 2009). Future research should also try to use more theory-driven questions to describe and explain the relationship between cancer information seeking and cancer-related outcomes. Only five studies included in this scoping review were informed by conceptual or theoretical framework.

Despite efforts to oversample non-Hispanic Blacks, the HINTS population is largely non-Hispanic White, higher SES US adults. Other racial groups (e.g., American Indian/Alaska Natives) are even less represented in HINTS data. We reviewed the full articles for only two studies that collected primary data either in an attempt to include a concept (e.g., numeracy) (Hay, 2015) that was not included in the HINTS data that they were interested in, or adapt the HINTS questions to be more culturally appropriate with their target population (e.g., Haitians, Hualapai Indians not represented or underrepresented in the HINTS data (Kobetz, Dunn Mendoza, Menard, et al., 2010; Teufel-Shone, Cordova-Marks, Susanyatame, Teufel-Shone, & Irwin, 2015). Results from this scoping review can inform other research study designs and primary data collection aimed at populations (e.g., minorities, low socioeconomic status) that are consistently underrepresented in the HINTS data. For example, the survey development process described by Teufel-Shone, et al. 2015 could be useful to future researchers in their selection and adaptation of HINTS questions to be used with other underrepresented populations. Addressing these gaps in the HINTS literature will likely increase the generalizability of HINTS data to non-White, less affluent populations.

Albeit not a longitudinal dataset, HINTS is a very valuable resource for studying cancer-related questions among smaller subpopulation (e.g., cancer survivors, smokers) because several questions are repeated across multiple survey iterations. This scoping review included a study that combined multiple years of HINTS data to examine the relationship between cancer information seeking and smoking status. While cancer in general is still a rare outcome, survivorship is an increasingly important issue as advances in treatment continue to be made. Thus, it will become increasingly important to be able to access a subpopulation of cancer survivors, and to do so using HINTS data would likely require the combination of multiple years of data. The Finney-Rutten, et al. 2009 study is an example that researchers can use in the future to conduct these more complex methodologies to produce larger samples for studying cancer-related outcomes among subpopulations such as smokers and cancer survivors.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. All studies we reviewed used a cross-sectional design. This limited our ability to assess any causal relationships between predictors and cancer information seeking, or cancer information seeking and cancer-related health outcomes. More rigorous study designs are needed to better assess cancer information seeking as cause or effect of cancer-related health outcomes. The fact that we focused on cancer information seeking (which is less studied compared to health information seeking in general) limited the total number of studies (n=22) that were included in this scoping review. However, we were able to not only review and include studies that focused on a variety of cognitive, psychosocial, and behavioral cancer-related health outcomes, but also studies that conceptualized cancer information seeking in various ways that included online and offline seeking, scanning and the interaction between seeking and scanning, seeking experiences and self-efficacy, and seekers’ information overload.

While ideally it would have been useful to examine studies that used more recent HINTS data, the fact that researchers continue to publish their findings in high impact journals underscores the richness of the HINTS datasets. We also were only able to report on one study (Finney-Rutten 2009) that used multiple years of HINTS data to achieve a larger sample of smokers for their study because no full text was available for the other two studies we identified that also used multiple years of HINTS data. The fact that HINTS collects data on the same variables across multiple years is definitely a major strength. We do note, however, that some years the HINTS questions were more heavily focused on cancer information seeking compared to other years. Also, over time, some questions about cancer information seeking have been dropped so that newer questions could be added to assess emerging trends (e.g., health communication between family members and friends) while at the same time minimizing the survey time burden on participants. For example, When was the most recent time you looked for information about cancer?, albeit very relevant in terms of providing context as opposed to having “ever” looked for information about cancer, is not assessed on the most recent iterations of the HINTS. Nonetheless, it is extremely valuable that researchers have the HINTS battery of questions about cancer information seeking that they can use to answer their research questions among their target populations. To this end, this is the first scoping review of HINTS studies that examined cancer information seeking. Therefore, this scoping review can serve as an important resource for helping other researchers to not only examine the relationship between cancer information seeking and cancer-related health outcomes, but further to be able to conceptualize the concept of cancer information seeking which can also include seeking experiences, self-efficacy, and information overload.

Conclusions

Cancer is a leading cause of death among US adults. Vulnerable populations such as racial/ethnic minorities and those of lower SES are disproportionately burdened by cancer disease and death. While the digital divide was previously based on the lack of infrastructure (Chandrasekhar and Ghosh, 2001), communication inequalities are now largely attributed to sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, age) and socioeconomic status (SES) (Pew Research Center, 2013; Kontos E, Bennett G, Viswanath K, 2007; Lorence, Park and Fox, 2006).

Although cancer information seeking has been shown to be positively associated with some cancer-related health outcomes (David & Case 2012; Shim 2006), cancer information seeking among US adults is suboptimal and has not changed much over the past decade. This review underscores the need for efforts aimed at improving positive predictors of cancer information seeking in an effort to increase the number of US adults who search for information about cancer and feel confident about being able to find and use cancer information if needed. These efforts should also focus on improving cancer information seeking experiences in an effort to reduce ambiguity about cancer risk, and minimize the number of consumers who feel overloaded by the plethora of information that they are able to find about cancer.

REFERENCES

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Arora NK, Hesse BW, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, Clayman ML, Croyle RT. Frustrated and confused: the American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(3):223–228. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0406-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics. Leading Causes of Death. [Last accessed on 8/31/2015. Page last reviewed on 1/20/2015];2015 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm. Page last updated on 8/21/2015.

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. York: University of York; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cerully JL, Klein WM, McCaul KD. Lack of acknowledgment of fruit and vegetable recommendations among nonadherent individuals: Associations with information processing and cancer cognitions. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(S1):103–115. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar CP, Ghosh J. Information and communication technologies and health in low income countries: the potential and the constraints. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2001;79(9):850–855. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Yamada T, Smith J. An evaluation of healthcare information on the internet: The case of colorectal cancer prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11(1):1058–1075. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110101058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. [Last accessed on 7/8/2015];2015 Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/ Last updated on 8/31/2015.

- Finney-Rutten LJ, Meissner HI, Breen N, Vernon SW, Rimer BK. Factors associated with men's use of prostate-specific antigen screening: evidence from Health Information National Trends Survey. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40(4):461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney-Rutten LJ, Augustson EM, Doran KA, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Health information seeking and media exposure among smokers: a comparison of light and intermittent tobacco users with heavy users. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(2):190–196. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JS, Coups EJ, Hay JL. Knowledge of colon cancer screening in a national probability sample in the United States. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(S1):19–35. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DB, Becofsky K, Anderson LA, Bryant LL, Hunter RH, Ivey SL, Lin SY. Public perceptions about risk and protective factors for cognitive health and impairment: a review of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics. 2015:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JG, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Moser RP, Leyva B, Breslau ES, Kobrin SC. Opportunities and Challenges for the Use of Large-Scale Surveys in Public Health Research: A Comparison of the Assessment of Cancer Screening Behaviors. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2015;24(1):3–14. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han PK, Moser RP, Klein WM, Beckjord EB, Dunlavy AC, Hesse BW. Predictors of perceived ambiguity about cancer prevention recommendations: Sociodemographic factors and mass media exposures. Health Communication. 2009;24(8):764–772. doi: 10.1080/10410230903242242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay J, Coups EJ, Ford J, DiBonaventura M. Exposure to mass media health information, skin cancer beliefs, and sun protection behaviors in a United States probability sample. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2009;61(5):783–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JL, Orom H, Kiviniemi MT, Waters EA. “I Don’t Know” My Cancer Risk Exploring Deficits in Cancer Knowledge and Information-Seeking Skills to Explain an Often-Overlooked Participant Response. Medical Decision Making. 2015;35(4):436–445. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15572827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, Case DO. Health Information Seeking. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaphingst KA, Lachance CR, Condit CM. Beliefs about heritability of cancer and health information seeking and preventive behaviors. Journal of Cancer Education. 2009;24(4):351–356. doi: 10.1080/08858190902876304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kealey E, Berkman CS. The relationship between health information sources and mental models of cancer: Findings from the 2005 Health Information National Trends Survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(sup3):236–251. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lustria MLA, Burke D, Kwon N. Predictors of cancer information overload: findings from a national survey. Information Research. 2007;12(4):12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kobetz E, Mendoza AD, Menard J, Rutten LF, Diem J, Barton B, McKenzie N. One size does not fit all: Differences in HPV knowledge between Haitian and African American women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2010;19(2):366–370. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos E, Bennett G, Viswanath K. Barriers and facilitators to home computer and Internet use among urban novice computer users of low socioeconomic position. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2007;9(4):e31. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.4.e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos EZ, Emmons KM, Puleo E, Viswanath K. Contribution of communication inequalities to disparities in human papillomavirus vaccine awareness and knowledge. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(10):1911–1920. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62(2):228–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010;5(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling BS, Klein WM, Dang Q. Relationship of communication and information measures to colorectal cancer screening utilization: results from HINTS. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(S1):181–190. doi: 10.1080/10810730600639190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorence DP, Park H, Fox S. Assessing health consumerism on the Web: a demographic profile of information-seeking behaviors. Journal of Medical Systems. 2006;30(4):251–258. doi: 10.1007/s10916-005-9004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madadi M, Zhang S, Yeary KHK, Henderson LM. Analyzing factors associated with women’s attitudes and behaviors toward screening mammography using design-based logistic regression. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2014;144(1):193–204. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2850-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Vernon SW, Meissner HI, Rakowski W. Risk perceptions and worry about cancer: does gender make a difference? Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13(1):56–79. doi: 10.1080/10810730701807076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey. [Last accessed on 7/8/2015]; (n.d.). Available at: http://hints.cancer.gov.

- National Cancer Institute. HINTS Brief 16: Trends in Cancer Information Seeking. [Last accessed on 6/23/2015];2010 Available at: http://hints.cancer.gov/briefsDetails.aspx?ID=235.

- Niederdeppe J. Beyond knowledge gaps: Examining socioeconomic differences in response to cancer news. Human Communication Research. 2008;34(3):423–447. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz AP, López M, Flores LT, Soto-Salgado M, Rutten LJF, Serrano-Rodriguez RA, Tortolero-Luna G. Peer Reviewed: Awareness of Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Tests and Use of Genetic Tests Among Puerto Rican Adults, 2009. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2011;8(5) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Who’s not online and why. [Last accessed on 8/31/2015];2013 Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/2013/PIP_Offline%20adults_092513_PDF.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Renton T, Tang H, Ennis N, Cusimano MD, Bhalerao S, Schweizer TA, Topolovec-Vranic J. Web-based intervention programs for depression: a scoping review and evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2014;16(9) doi: 10.2196/jmir.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim M, Kelly B, Hornik R. Cancer information scanning and seeking behavior is associated with knowledge, lifestyle choices, and screening. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(S1):157–172. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim M. Connecting Internet use with gaps in cancer knowledge. Health Communication. 2008;23(5):448–461. doi: 10.1080/10410230802342143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel-Shone NI, Cordova-Marks F, Susanyatame G, Teufel-Shone L, Irwin SL. Documenting cancer information seeking behavior and risk perception in the Hualapai Indian community to inform a community health program. J Community Health. 2015;40(5):991–998. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Cai X. The role of risk, efficacy, and anxiety in smokers' cancer information seeking. Health Communication. 2009;24(3):259–269. doi: 10.1080/10410230902805932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Cancer information disparities between US-and foreign-born populations. Journal of health Communication. 2010;15(sup3):5–21. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]