Abstract

This study examines clinical and family predictors of perceived need for treatment and engagement in mental health treatment services among community-referred racial/ethnic minority adolescents and their primary caregivers. Findings indicated that the majority of families perceived a need for treatment, but that perceived need was not associated with treatment engagement. Family factors (i.e., low cohesion and high conflict within the family) predicted perceived need for treatment among adolescents, whereas clinical factors (i.e., adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptomatology) predicted caregiver perceived need for adolescent treatment. Neither clinical nor family factors predicted treatment engagement.

Keywords: perceived need for treatment, treatment engagement, racial/ethnic minority youth, unmet treatment need

Despite the availability of promising efficacious mental health treatments for youth (e.g., Chorpita et al., 2011), a substantial proportion of juvenile mental health needs go largely unmet, with only one-fourth to one-half of youth with mental health disorders receiving treatment (Costello, He, Sampson, Kessler, & Merikangas, 2014; Merikangas et al., 2010). Of particular concern, research suggests that racial/ethnic minority youth are less likely to seek professional mental health treatment compared to White youth, (Alegría et al., 2012; Alegría, Vallas, & Pumariega, 2010; Garland et al., 2005), despite demonstrating similar, if not higher, treatment needs (e.g., Merikangas et al., 2010). Given this high unmet mental health need, the present study aimed to determine predictors of perceived need for treatment and engagement in outpatient mental health services among community-referred racial/ethnic minority adolescents. Identification of such predictors can be helpful in efforts to improve access to and uptake of behavioral health services among youth in need of services.

Previous research examining predictors of treatment service use among adolescent populations has primarily focused on relations between client-centered variables—usually demographics and some measure of clinical status—and treatment engagement. Many of these studies were guided by a well-validated, multi-level theoretical model, Andersen’s behavioral model of healthcare use (Andersen, 2008), which posits that there are three main influences on whether a person seeks treatment for his or her problems: (1) need for services (e.g., clinical status such as diagnoses and severity of symptoms), (2) predisposing characteristics (e.g., demographic factors), and (3) enabling characteristics (e.g., insurance status). Findings from these studies for youth populations reveal that need variables are the most significant predictors of mental health service use, while predisposing and enabling characteristics typically account for little additional variance (Babitsch, Gohl, & von Lengerke, 2012).

Need for services is typically demonstrated by level of symptom severity, type of disorder, and psychiatric co-morbidity. In particular, youth who exhibit (a) more severe symptomatology (Leaf et al., 1996; Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002; Merikangas et al., 2010, 2011), (b) symptoms that rise to levels that meet diagnostic criteria for mental health disorders (Burns et al., 1995; Cheng & Lo, 2010), (c) externalizing (rather than internalizing, substance use, or eating) problems (Brannan, Heflinger, & Foster, 2003; Merikangas et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2001), and/or (d) psychiatric comorbidity (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Hogue & Dauber, 2011; Storr, Accornero, & Crum, 2007) are more likely to seek treatment due a perception of need on their own or a caregiver’s behalf. However, Hispanic and African American families are significantly less likely than White families to seek treatment for adolescent mental health problems, regardless of level of need (Angold et al., 2002; Flisher et al., 1997; Kataoka et al., 2002; Leaf et al., 1996; Merikangas et al., 2010; Pumariega, Glover, Holzer, & Nguyen, 1998). Perceived need encompasses motivation, which can be a result of intrinsic or extrinsic pressure to seek out treatment services (Leon, Melnick, Kressel, & Jainchill, 1994).

The extent to which predisposing or enabling factors contribute to treatment seeking is less clear, given inconsistent findings in prior research. Some studies have identified significant predisposing and enabling factors, including adolescent gender and age, caregiver education level and marital status, and medical insurance coverage (Alexandre, Dowling, Stephens, Laris, & Rely, 2008; Cheng & Lo, 2010; Elhai & Ford, 2007; Freedenthal, 2007; Phillips, Morrison, Andersen, & Aday, 1998; Solorio, Milburn, Andersen, Trifskin, & Rodríguez, 2006). However, many studies have failed to take into account important covariation among need, predisposing, and enabling factors. For example, some studies indicate that boys are more likely than girls to use mental health services (Burns et al., 1995; Padgett, Patrick, Burns, & Schlesinger, 1994). This could be attributed to the fact that boys are more likely to exhibit externalizing problems (which, as described above, are more strongly associated with receipt of services) while girls are more likely to exhibit internalizing problems (e.g., Achenbach, Howell, McConaughy, & Stanger, 1995). Similarly, sociodemographic data tend to covary and therefore may reflect the influence of socioeconomic status (SES) and the larger societal system influences on service use. For example, caregivers who have reached higher education levels are likely to be of higher socioeconomic status and therefore may have higher income and better access to health insurance compared to lesser educated caregivers and low-income families, which may mean more access to services. Although this prior work has explained some of the variance in service use among adolescent samples, some posit that the model is not thoroughly explanatory due to its exclusive focus on youth-centered variables, which do not account for vital developmental and ecological information, particularly the role of family factors.

Family Predictors of Mental Health Treatment Attitudes and Engagement

Along with individual-level factors, family factors appear to play a key role in perceived need for and engagement in mental health treatment for adolescents. Youth typically do not seek out professional services on their own, but instead seek help from networks of support (e.g., parents, school personnel). When professional services are sought, youth tend to be directed to them by primary caregivers, teachers, juvenile justice authorities, and other adults, given that guardian permission is required to access services and insurance (Schonert-Reichl, Offer, & Howard, 2013; Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, 2010). Of particular relevance to racial/ethnic minority youth, familial support in accessing services may be limited due to specific cultural attitudes and beliefs (e.g., stigma, mistrust, disparate definitions of mental illness) that may influence caregivers’ perceptions of needing or wanting mental health treatment for their child (Abdullah & Brown, 2011; Corrigan, Druss, & Perlick, 2014). Therefore, research on ethnic/racial minority adolescent populations is needed that shifts away from focusing primarily on client-centered predictors of treatment-seeking and service use to a developmental-ecological approach that integrates influences from the adolescent’s environment and centralizes the influence of family.

Research consistently suggests that family relationship dynamics significantly impact the home environment and therefore adolescent development, and can play a role in family decisions to seek out treatment services for youth emotional and behavioral problems. In particular, youth who experience cold, unsupportive, and neglectful home environments, as well as those characterized by overt conflict, including recurrent episodes of anger and aggression, are at increased risk for mental health problems (e.g., Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002; Sheidow, Henry, Tolan, & Strachan, 2014). Although some research suggests that youth from home environments characterized by poor relationship dynamics are more likely to seek out treatment services (Gopalan et al., 2010), work is still needed to determine (a) whether need for such services is perceived by both adolescents and their caregivers and (b) the extent to which these families succeed in engaging in services.

Adolescent perceptions of caregivers’ parenting practices, and in particular their perspective of the capacity that caregivers have to enact and enforce rules (i.e., parental containment; Schneider, Cavell, & Hughes, 2003), can also shape the family environment and therefore influence engagement in mental health services. Although some studies have examined the impact of parental monitoring on youth adherence to medical treatment services (e.g., Hommel, Odell, Sander, Baldassano, & Barg, 2011; Palmer et al., 2011), research into the influence of parenting practices on engagement in mental health treatment services is scarce. Luthar and Goldstein (2008) found that adolescents’ perceptions of parental containment were associated with externalizing behavior—that is, adolescents who perceived more rules and stricter rule enforcement by caregivers were less likely to engage in substance use, delinquency, and rule breaking. Given this finding, it is possible that perceptions of treatment need are higher for caregivers who exercise lower levels of parental containment. In addition, adolescent perceptions of parental containment, and particularly the extent to which they believe they must adhere to caregiver rules, may influence engagement in treatment services.

It is particularly important to understand the impact of family factors on perceptions of treatment need and engagement in services for African American and Hispanic families in the U.S. Racial/ethnic minority youth and adults are less likely to access mental health treatment services (Alegría et al., 2012; Alegría et al., 2010) and demonstrate higher rates of stigma associated with mental illness (Abdullah & Brown, 2011). In addition, authoritarian parenting styles are more common among racial/ethnic minority caregivers (Weis & Toolis, 2010) and thereby may be more central in determining the extent of adolescent treatment engagement compared to families who take more authoritative or permissive approaches to parenting. And finally, racial/ethnic differences in SES have led to differences in neighborhood quality and conditions, meaning that African American and Hispanic communities often lack adequate community-based opportunities and resources, including access to high quality healthcare (Williams, Mohammed, Leavell, & Collins, 2010). To mitigate these differences, it is critical to learn more about the influence of both adolescent clinical symptomatology and family factors of perceptions of treatment need and treatment engagement specifically for African American and Hispanic youth.

The Present Study

Perceived need for treatment has been proposed as an important first step in the path to seeking mental health treatment (Andrade et al., 2014). Because the vast majority of adolescents with mental health problems do not seek professional help (Merikangas et al., 2010), it is important to differentiate whether these youth and their families feel the need to seek help but do not translate this need into action, or do not perceive any need for treatment at all. Further, although family variables have emerged as important influences on how adolescents utilize mental health services (e.g., Gopalan et al., 2010), further research is needed to examine whether these factors predict perceptions of treatment need and the extent to which treatment services are utilized, particularly for racial/ethnic minority youth. To address these issues, this study used data from a sample of community-referred racial/ethnic minority adolescents and their primary caregivers to examine clinical and family predictors of perceived need for treatment and engagement in outpatient mental health treatment services. Study hypotheses were as follows:

In addition to adolescent clinical symptomatology (i.e., internalizing and externalizing problems), family characteristics (i.e., family cohesion and conflict; parental containment) would predict perceived need for treatment.

Over and above adolescent clinical symptomatology and demographic characteristics, family characteristics would predict intake attendance and treatment initiation.

This study aims to contribute to the literature in a number of ways. First, it incorporates multidimensional conceptualizations of adolescent clinical symptomatology, family factors, and perceived need for treatment by including data reported by both caregivers and adolescents. Because youth and caregivers typically show weak concordance on measures of psychological symptoms leading to referral, family-based assessment is essential for capturing a complete picture of perceived treatment need (e.g., De Los Reyes et al., 2015). Further, research shows that adolescents are better at recognizing mental health problems in themselves than parents are in recognizing such problems in their children (Williams, Lindsey, & Joe, 2011). However, youth may benefit from assistance from gateway providers (e.g., caregivers, school personnel, juvenile justice) in accessing mental health services (McKay & Bannon, 2004). Thus, information on predictors of perceived need and treatment engagement from multiple perspectives is critical to better inform how this treatment-seeking collaboration could work best for families.

Second, this study provides a prospective account of perceptions of treatment needs and service utilization among youth currently experiencing mental health problems. To date, extant literature primarily encompasses retrospective studies of treatment-seeking (e.g., Merikangas et al., 2011) or studies that use hypothetical scenarios to determine what youth would do if they needed help in the future (e.g., Mojtabai, 2007; Oliver, Pearson, Coe, & Gunnell, 2005). Reliance on retrospective reports from youth with past involvement in treatment systems is problematic because youth who are involved in multiple systems of care typically demonstrate poor recall of past services received and the context of service provision (e.g., identification of the professional designations of their providers and system affiliations; Li, Liebenberg, & Ungar, 2015). Reliance on hypothetical scenarios regarding perceptions of need and treatment-seeking raises concerns similar to those posed by economists regarding the hypothetical bias (e.g., Loomis, 2011) – that is, when asked to imagine how much they would pay for a product, participants proffer substantially less than they would pay in an actual transaction. Thus, research focusing on families that are currently experiencing such problems is more likely to result in accurate and generalizable findings.

Finally, participants in this study constitute a sample of racial/ethnic minority youth with unmet treatment needs and their primary caregivers, who experience unique cultural risk factors that likely impact perceptions of, and access to, treatment. Study recruitment procedures were designed to identify adolescents with untreated mental health or substance use disorders and to assist them in enrolling in available community-based treatment services. To recruit adolescents with unmet treatment needs, research staff developed a referral network of high schools, family service agencies, and youth programs in inner-city areas within New York City. Referrals were made for youth between 12–18 years of age living with a primary caregiver and not currently receiving treatment, but who were observed or suspected by a referral partner as having significant behavioral problems deemed beyond the scope of routine services available within the referral network (e.g., guidance/counseling services at schools, case management in family agencies). As described in detail below, upon entry into the study, youth were then linked to appropriate behavioral treatment services with extensive support provided by research staff in attending a first intake appointment.

Method

Study Design and Participants

Data for this study were collected as part of a randomized trial focused on assessing the effectiveness and implementation quality of routine family therapy compared to usual-care behavioral health services delivered in naturalistic settings with a sample of ethnically and racially diverse youth (see Hogue et al., 2015 for details). The subsample in the present study consisted of 187 adolescents (Mage = 15.6 years, SD = 1.4 years) and their primary caregivers residing in New York City. From the larger trial (N = 205), 18 families were not included due to missing data on some or all of the outcome variables. Participating families experienced high levels of systems involvement and high rates of behavioral health problems with substantial comorbidity (Dauber & Hogue, 2011; Hogue & Dauber, 2011). Adolescent and family demographic characteristics, including youth psychiatric diagnoses, are presented in Table 1. Sixty percent of the adolescents in this sample self-identified as Hispanic (n = 112), 21% as African American (n = 40), 15% as multiracial (n = 28; predominantly Hispanic and African American), and 4% as a different racial/ethnic background (e.g., White, Asian; n = 7).

Table 1.

Adolescent and family demographic characteristics

| Adolescent Characteristic | % |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 51 |

| Female | 49 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 60 |

| African American | 21 |

| Multiracial | 15 |

| Other | 4 |

| DSM-IV diagnoses | |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 86 |

| Conduct disorder | 53 |

| Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder | 71 |

| Mood disorder | 41 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 17 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 18 |

| Substance use disorder | 29 |

|

| |

| Family Characteristics | % |

|

| |

| Household composition | |

| Single-parent household | 67 |

| Two-parent household | 24 |

| Grandparent-headed household | 6 |

| Other | 3 |

| Caregiver graduated high school | 70 |

| Caregiver employed | 63 |

| Household income > $22,000 | 38 |

| Caregiver ever received public assistance | 18 |

| History of child welfare system involvement | 53 |

| Household member ever used illegal drugs | 33 |

| Household member engaged in illegal activity | 19 |

Referral network partners recruited participants and made referrals to research staff during site visits and also by phone and confidential email. Study staff then contacted referred families by phone and offered them an opportunity to participate in a home-based family research interview to assess the reason for study referral and discuss current developmental challenges. Adolescents were referred primarily from school staff (79%), but also from community-based family service agencies (12%), juvenile justice or child welfare sources (5%), and other sources (4%). Family eligibility criteria were assessed during this initial interview and included the following: (1) adolescent age 13–18; (2) one primary caregiver willing to participate in treatment; (3) adolescent met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, and/or Substance Use Disorder; (4) family was motivated to attend outpatient behavioral health treatment, and the adolescent was not participating in any other behavioral treatment; (5) adolescent had insurance coverage accepted at study treatment sites. Within two weeks of this screening, eligible families interested in seeking treatment participated in the baseline phase of the study, consisting of a second home-based research interview, randomization to treatment condition, and linkage to the designated treatment services.

Linkage to treatment was a unique feature of this study and entailed family engagement and case management procedures undertaken by research staff, which were designed to counteract common barriers to accessing and enrolling in outpatient mental health treatment, including time demands, scheduling conflicts, privacy concerns, affordability, and logistical barriers (e.g., lack of transportation, waitlists). Research staff provided both instrumental support (e.g., physically accompanying families to intake appointments, supplying public transportation fare, providing reminder phone calls to adolescents and caregivers) and relational support (e.g., education on the nature of counseling and other clinic processes, encouragement to hesitant, nervous, or skeptical adolescents and caregivers) to assist families in attending an initial intake appointment. All study families were provided with linkage to an initial intake appointment, and some families also accepted linkage support to additional intake interviews and/or the first session of treatment. Because this linkage was an important component of the research design, analyses examining treatment engagement controlled for the amount of instrumental and relational support that was provided to families (described below).

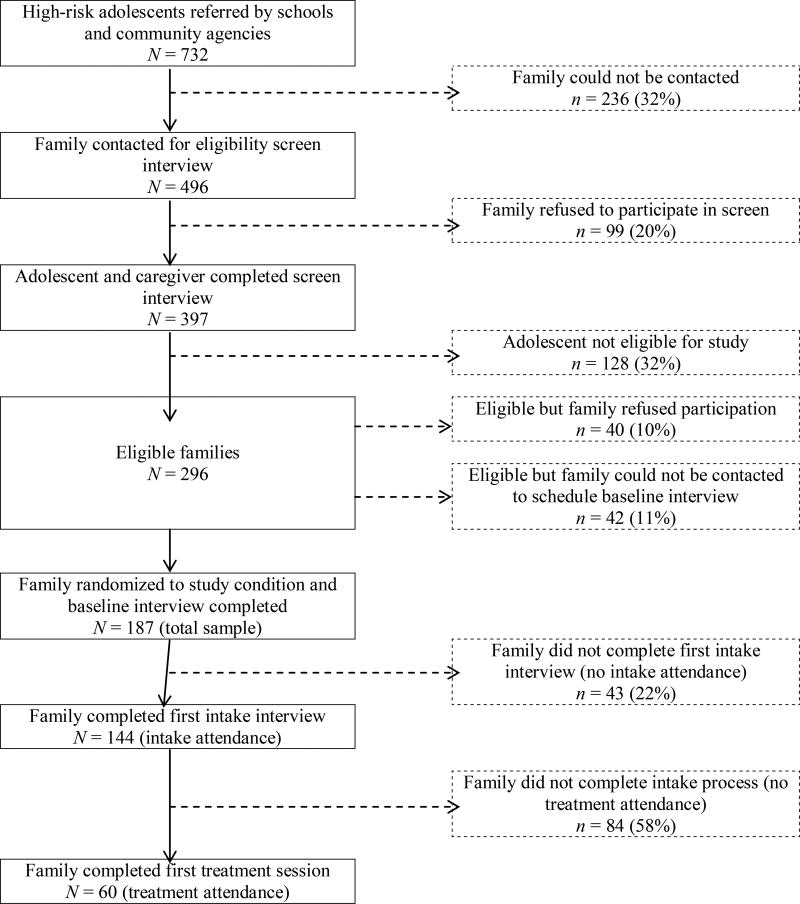

Six outpatient clinical treatment sites accepted study cases as standard community referrals. Therapists at each site volunteered to participate in the study and did not receive any external training, financial or logistical support, or requests to alter their routine clinical practices in any way. Participating clinics were easily accessible via public transportation and provided usual-care services to study families, consisting of weekly treatment sessions and in-house psychiatric support. Study referral, assessment, and treatment engagement rates are summarized in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Measures

Data for this study were collected during home-based structured interviews with adolescents and participating caregivers and also from clinic records. Caregiver interviews were administered in the preferred language (77% English, 23% Spanish) and both caregivers and adolescents received vouchers for completing their respective interviews.

Perceived need for treatment

Two items adapted from the Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1992) were used to assess perceived need for treatment whenever either an adolescent or caregiver reported adolescent clinical symptoms that met full criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis: “During the past month, how much have you been troubled or bothered by [fill in the endorsed DSM-IV symptoms]?” and “Is treatment in this area important to you, and if so, how much?” Participants responded not at all (0), a little (1), or a lot (2) to both items and scores were averaged across all positive diagnoses. DSM-IV diagnoses were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Version 5.0; Sheehan et al., 1998) and included oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for both adolescents and caregivers. In addition, adolescent assessments included major depressive disorder, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, alcohol use disorder, and marijuana use disorder. The final perceived need for treatment score was computed by summing the mean troubled/bothered score with the mean treatment importance score. This operationalization has been used successfully in prior research with this sample (Hogue, Dauber, Lichvar, & Spiewak, 2014).

Intake attendance and treatment initiation

Data on the number of appointments kept were recorded by participating therapists. Intake attendance was defined as attending an intake session at the assigned treatment site. Treatment initiation was defined as the completion of an initial treatment session after completing the full intake process at the assigned treatment site.1

Adolescent symptomatology

Adolescent clinical symptomatology was assessed with the adolescent-reported Youth Self-Report (YSR) and caregiver-reported Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Dumenci, 2001). These parallel measures of youth behavioral and emotional problems yield a number of subscales, some of which assess internalizing problems (i.e., social withdrawal, somatic complaints, anxiety/depression) and externalizing behavior (i.e., delinquency, aggression) and were used in the present study. Respondents are instructed to indicate how true each statement is based on a 3-point Likert-type scale: not true at all (0), somewhat or sometimes true (1), or very or often true (2). The validity and reliability of the YSR and CBCL have been widely documented with diverse populations of adolescents (e.g., Dakof, Tejeda, & Liddle, 2001; Doyle, Mick, & Biederman, 2007). With the present sample, internal consistency ratings suggested acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = .89 − .93 for internalizing and externalizing scales of the YSR and CBCL). This is consistent with reliability reported from previous studies using these measures (e.g., Achenbach 1991a; 1991b; Achenbach & Dumenci, 2001).

Family environment

Both adolescents and caregivers reported on family environment using the Relationship Dimension from the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1994). This dimension includes two 10-item subscales of engagement among family members: cohesion and conflict. Study participants were asked to indicate whether each item was true (1) or false (0) (e.g., “Family members rarely become openly angry”; “Family members really help and support one another”), with item scores summed and higher scores indicating more family stress. Moos and Moos (1994) documented acceptable internal consistencies and good validity of these two subscales. In the present study, internal consistencies for these subscales were acceptable and within range of prior studies (Cronbach’s α = .50 − .68), but were somewhat lower than other measures included in this study.

Perceived parental containment

Adolescents responded to a youth-report version of the Parental Containment Scale for Children (Schneider et al., 2003), which assesses adolescents’ beliefs that particular deviant behaviors would elicit stringent disciplinary repercussions from caregivers (Luthar & Goldstein, 2008). This 14-item scale, consisting of four subscales of errant behavior (i.e., substance use, delinquency, rudeness, academic disengagement), asks respondents to indicate how serious the consequences from caregivers would be if they were discovered engaging in specific behaviors (e.g., rude to an adult relative; played truant from school on the day of an important exam) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all serious, 3 = moderately serious, 5 = extremely serious). Internal consistency with the current sample demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = .90). The validity of this measure has been established in prior research (Luthar & Goldstein, 2008).

Statistical Analysis

First, preliminary analyses examined differences in all study variables by adolescent demographic characteristics: gender, ethnicity, age, household income, and caregivers’ education. Second, hierarchical linear regression analysis was utilized to examine the extent to which adolescent clinical symptomatology and family factors predicted (1) adolescents’ perceived need for treatment and (2) caregivers’ perceived need for treatment for their adolescents. Demographic covariates were entered into Step 1, adolescent symptomatology was entered into Step 2, and family factors (i.e., family cohesion and conflict; parental containment) were entered into Step 3. Third, logistic regression models were run to examine the impact of adolescent symptomatology and family factors on (3) intake attendance and (4) treatment initiation. In each of these models examining treatment engagement, all independent variables, including demographic covariates (i.e., gender, ethnicity, age, household income, and caregivers’ education), were entered simultaneously. Linkage to treatment was also included as a covariate to indicate whether families were provided with linkage services only to the initial intake (coded as 0) or whether the linkage process extended to additional sessions after this first appointment (coded as 1). As reported by Hogue and colleagues (2015), there were no between-condition (family-based vs. non-family treatment clinics) differences in attending a first intake session or in total number of treatment sessions completed, so study condition was not included as a covariate. Given the very small percentage of missing data for all study variables (0–6%), listwise deletion was used.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Rates of DSM-IV diagnoses were high among adolescents in the study sample, based on both adolescent self-reports and caregiver reports (see Table 2), and mean perceived need for treatment scores were significantly correlated with the number of diagnoses for which youth met diagnostic criteria (r = .53 and .69, p’s < .001, for adolescent and caregiver reports, respectively). Descriptive analyses indicated that the majority of adolescents (64%) and caregivers (82%) perceived some degree of need for treatment (95% of families combined). Perceived need scores, ranging between 0 and 4, were significantly higher for caregivers (M = 2.82, SD = 1.56) than for adolescents (M = 1.52, SD = 1.35; t = 7.84, p < .001). Adolescent and caregiver perceived need scores were not significantly correlated (r = −.11, p = .16); 24.0% of caregivers and 38% of adolescents did not perceive any need for treatment.

Table 2.

Proportion of adolescents meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and associated mean perceived

| Adolescent-Reported

|

Caregiver-Reported

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Dx | PNT | Positive Dx | PNT | ||

|

|

|

||||

| % | M | % | M | ||

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 61.8 | 1.97 | 67.0 | 3.46 | |

| Conduct Disorder | 40.3 | 1.82 | 33.5 | 3.61 | |

| Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder | 38.4 | 2.03 | 55.7 | 3.46 | |

| Major Depressive Disorder/Dysthymia | 41.0 | 2.40 | -- | ||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 16.7 | 2.65 | -- | ||

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 17.7 | 2.44 | -- | ||

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 11.3 | 1.65 | -- | ||

| Marijuana Use Disorder | 23.1 | 1.46 | -- | ||

| 0 disorders | 16.1 | 0.00 | 18.9 | 0.00 | |

| 1 disorder | 15.1 | 1.00 | 25.4 | 3.17 | |

| 2 disorders | 23.1 | 1.68 | 36.2 | 3.48 | |

| 3 disorders | 17.2 | 2.01 | 19.5 | 3.66 | |

| 4 disorders | 15.1 | 2.12 | -- | ||

| 5 disorders | 5.4 | 2.48 | -- | ||

| 6 disorders | 7.0 | 2.37 | -- | ||

| 7 disorders | 1.1 | 2.57 | -- | ||

| 8 disorders | 0.0 | -- | -- | ||

Note. With the exception of alcohol and marijuana use disorders, mean adolescent-reported PNT scores were significantly higher among adolescents meeting diagnostic criteria for each disorder compared to mean PNT scores for those who did not meet diagnostic criteria (p’s < .05). Mean caregiver-reported PNT scores were significantly higher for those who reported that their child met diagnostic criteria for all three externalizing disorders compared to those whose children did not meet diagnostic criteria (p’s < .001).

Dx = diagnosis. PNT = perceived need for treatment.

As shown in Figure 1, almost a quarter of adolescents never attended an intake session (23%); of those who did, 59% did not attend an initial treatment session. Bivariate analyses indicated that adolescent and caregiver perceived need scores were not significantly associated with intake attendance (OR = 1.0, p = .99 and OR = 1.04, p = .72, respectively) or treatment initiation (OR = 1.22, p = .10 and OR = .99, p = .96, respectively).

Adolescent females had higher perceived need scores compared to adolescent males (t = 4.99, p < .001) and females were more likely to attend a treatment session than males (χ2 = 3.68, p < .05). There were no racial/ethnic differences in any of the outcome variables and no significant demographic differences in caregiver perceived need scores. In addition, few gender and racial/ethnic differences were identified among the adolescent-reported clinical and family predictors. Adolescent females reported more internalizing symptoms (t = 5.71, p < .001), externalizing symptoms (t = 3.33, p < .001), and family conflict (t = 2.19, p < .01) than adolescent males. Hispanic adolescents reported higher levels of parental containment (F = 2.79, p < .05). There were no significant gender or racial/ethnic differences in parent reports of adolescent clinical symptomatology or family predictors.

Predicting Perceived Need and Treatment Engagement

Results of the hierarchical linear regression models examining predictors of perceived need for treatment are presented in Table 3. Findings indicated that adolescent clinical symptomatology did not predict adolescents’ perceived need for treatment, but did predict greater perceived need for adolescent treatment among caregivers. Regarding the family predictors, results indicated that lower levels of adolescent-reported family cohesion and higher levels of adolescent-reported family conflict significantly predicted greater perceived need for treatment among adolescents. None of the family factors examined predicted caregivers’ perceived need for treatment for their adolescents. Adolescent females perceived a greater average need for treatment than adolescent males, although adolescent gender did not predict level of caregivers’ perceived need for treatment.

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear regression results of the impact of adolescent clinical symptomatology and family factors on perceived need for treatment

| Adolescents’ Perceived Need for Treatment |

Caregivers’ Perceived Need for Adolescent Treatment |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | ΔR2 | F | β | ΔR2 | F | β |

| Step 1 | .18*** | 4.88*** | .02 | 0.53 | ||

| Gender | 1.02*** | −.15 | ||||

| Age | .09 | −.06 | ||||

| Hispanic | .54 | −.56 | ||||

| African American | .47 | −.53 | ||||

| Multiracial | .95 | −.68 | ||||

| Household Income | .27 | .16 | ||||

| Caregiver Education | −.04 | .38 | ||||

| Step 2 | .05*** | 2.05 | .17*** | 7.93*** | ||

| Internalizing1 | .02 | .00 | ||||

| Externalizing1 | .02 | −.02 | ||||

| Internalizing2 | −.01 | −.02 | ||||

| Externalizing2 | .00 | .06*** | ||||

| Step 3 | .07*** | 2.84* | .02** | 0.44 | ||

| Cohesion1 | −.11* | .06 | ||||

| Conflict1 | .13* | .01 | ||||

| Cohesion2 | .04 | .04 | ||||

| Conflict2 | .00 | −.02 | ||||

| Containment | .00 | .00 | ||||

| Total R2 | .30*** | .21** | ||||

Note. Variable = adolescent-reported.

Variable = caregiver-reported.

Results from the logistic regression models examining predictors of intake attendance and treatment initiation, presented in Table 4, indicated that none of the adolescent clinical or family factors predicted these outcomes. However, three covariates—adolescent age, gender, and household status—emerged as significant predictors of treatment initiation. Specifically, females and older adolescents were more likely to engage in treatment, as were those from households with income greater than $22,000, which represented the federal poverty level at the time of study data collection.

Table 4.

Logistic regression results of the impact of adolescent clinical symptomatology and family factors on treatment engagement

| Intake Attendance

|

Treatment Attendance

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Gender | 0.86 | [0.34, 2.15] | 3.62** | [1.37, 9.60] |

| Age | 1.02 | [0.75, 1.38] | 1.41* | [1.00, 1.98] |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.17 | [0.38, 3.56] | 0.42 | [0.13, 1.37] |

| African American | 0.74 | [0.25, 2.20] | 0.72 | [0.18, 2.80] |

| Multiraciala | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Household Income | 1.17 | [0.49, 2.80] | 0.30 | [0.11, 0.81] |

| Caregiver Education | 0.83 | [0.31, 2.19] | 1.41 | [0.53, 3.74] |

| Treatment Site | ||||

| Clinic 1 | 1.61 | [0.27, 9.50] | 0.48 | [0.05, 4.37] |

| Clinic 2 | 0.50 | [0.12, 2.08] | 0.63 | [0.13, 3.05] |

| Clinic 3 | 3.82 | [0.42, 34.84] | 2.06 | [0.56, 7.54] |

| Clinic 4 | 1.48 | [0.41, 5.31] | 0.17 | [0.01, 1.93] |

| Clinic 5 | 0.91 | [0.19, 4.14] | 2.03 | [0.74, 5.54] |

| Linkageb | -- | -- | 1.01 | [0.94, 1.08] |

| Adolescent Clinical Factors | ||||

| Internalizing1 | 1.01 | [0.94, 1.08] | 0.99 | [0.92, 1.06] |

| Externalizing1 | 1.01 | [0.95, 1.08] | 0.99 | [0.92, 1.05] |

| Internalizing2 | 0.99 | [0.93, 1.05] | 1.02 | [0.97, 1.06] |

| Externalizing2 | 0.99 | [0.95, 1.28] | 0.92 | [0.72, 1.18] |

| Family Factors | ||||

| Cohesion1 | 1.02 | [0.82, 1.28] | 0.93 | [0.72, 1.19] |

| Conflict1 | 0.99 | [0.79, 1.25] | 1.20 | [0.95, 1.50] |

| Cohesion2 | 0.84 | [0.68, 1.05] | 0.97 | [0.74, 1.27] |

| Conflict2 | 0.92 | [0.72, 1.17] | 1.00 | [0.95, 1.05] |

| Containment | 1.01 | [0.96; 1.05] | 0.59 | [0.11, 3.10] |

Note. Cell values were too small to compute.

Linkage was only included in the treatment attendance analysis.

Variable = adolescent-reported.

Variable = parent-reported.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Discussion

This study aimed to understand the impact of caregiver and adolescent perceptions of adolescent clinical symptomatology and family factors on caregiver and adolescent perceived need for adolescent treatment and engagement in treatment among a sample of community-referred ethnic minority families with unmet behavioral health needs. Overall, findings indicated that the majority of families perceived a need for treatment, with different factors influencing adolescents’ versus caregivers’ perceived need for treatment. Interestingly, perceived need for treatment was not associated with treatment engagement among this sample. Family factors (i.e., low family cohesion, and high family conflict) predicted whether adolescents believed they needed services, whereas adolescent clinical factors (i.e., internalizing and externalizing symptomatology) predicted whether caregivers believed this. Contrary to hypotheses, neither family nor adolescent characteristics predicted whether adolescents completed intake or attended a first treatment session.

Prior research has demonstrated that there is low concordance on perceived need for treatment among racial/ethnic minority youth and their caregivers and has led researchers to advocate for consideration of both adolescent and caregiver perceptions of treatment need (e.g., Williams et al., 2011). Findings from the present study provide further rationale for this consideration. Discordant predictors of perceived treatment need between adolescents and their primary caregivers may be a result of family contextual stressors that drive breakdowns in communication, strained and contentious relationships, and differing perspectives about the family unit’s primary “problem”. These findings may demonstrate that caregiver perception of treatment need is congruent with the symptom-focused approach typically taken by clinicians when evaluating adolescent emotional and behavioral problems. Alternatively, it may be that adolescent externalizing behavior is often disruptive to the environment and more observable and troubling to caregivers than are family stressors, which may be perceived by caregivers as normative while youth move through adolescence (Arnett, 1999; 2014). In either case, these findings suggest that caregivers’ perceived need for treatment is related to adolescents’ clinical symptoms.

This association may also be driven by higher sensitivity among economically disadvantaged racial/ethnic minority caregivers to the high-stakes consequences of their children’s externalizing problems (e.g., legal involvement, detention) (Marrast, Himmelstein, & Woolhandler, 2016) and may accordingly seek professional help to preempt such circumstances. Although in the present study economically disadvantaged families were less likely to engage in treatment, they were not less likely to perceive a need for treatment. This discordance suggests that substantial barriers to treatment may exist for those who are economically disadvantaged, even when their perceptions of need are strong. Compared to caregivers with more social capital, these caregivers may be less able to help their children avoid system involvement and protect them from the cascade of life-altering events that can often follow severe externalizing behavior. There is a host of research showing that African American youth with emotional and behavioral problems are more likely to end up in the juvenile justice system than White youth (e.g., Davis & Sorensen, 2013; Desai, Falzer, Chapman, & Borum, 2012). Interpreted this way, these caregivers’ perceived need for treatment may be influenced not only by adolescent clinical factors, but also by interactions among the individual, family, beliefs regarding mental health and help-seeking, and broader systemic factors. Testing such interactions was beyond the scope of this study, but should be considered in future studies examining predictors of treatment need and engagement.

The finding that adolescents’ perceptions of treatment need were predicted by family factors supports prior research suggesting that caregiver and family factors such as parental psychopathology, living in a one-parent family, changes in family composition, and family conflict are particularly observable and troubling to youth and can lead to increased behavior problems (Murray& Farrington, 2010). Interestingly, the literature is inconclusive on the role of adolescent clinical factors on adolescents’ perceived need for treatment. Despite the high levels of externalizing disorders among the sample in the present study, this behavior itself was not predictive of perceptions of treatment need; instead, microsystemic problems within the family unit were more likely to signal treatment need.

Although the majority of participating families perceived some degree of need for treatment and attended an initial intake session, less than one-third of families in the study attended any treatment sessions beyond this. Although these numbers are in line with other studies examining treatment engagement (McKay, Lynn, & Bannon, 2005), this finding is concerning given that research staff in the current study dedicated substantial time to implementing linkage procedures that were specifically designed to remove many of the common logistical barriers that often prevent families from enrolling in outpatient mental health treatment. Prior research has identified client-centered and family-level predictors to adolescent treatment engagement, including gender, clinical impairment level, family poverty, caregiver and family stress, effectiveness of parental discipline, and family cohesion and organization (Gopalan, et al., 2010). In the present study, however, neither adolescent clinical symptomatology nor family factors (i.e., cohesion, conflict, parental containment) significantly predicted intake or treatment attendance. This inconsistency with prior literature may be due to the fact that youth and their families who agreed to participate in the present study were not actively seeking treatment at the time of study recruitment. This may have led to reduced motivation to make progress in fully engaging in treatment and should be further explored in future research examining barriers to navigating through the various steps involved in the treatment seeking process.

During the intake process, families likely learned of the commitment (e.g., time demands) and possible costs (e.g., transportation) that attending treatment requires. These and other barriers to treatment, including contextual barriers (e.g. crises at home, community violence), and agency barriers (e.g., time spent on waiting lists, scheduling of appointment times) may prevent families from utilizing services (Ingoldsby, 2010; Mojtabai et al., 2011). In addition, prior research has noted that perceived barriers related to caregiver attitudes regarding help-seeking (e.g., having to give too much personal information in treatment), perceptions of treatment relevance, and the potential helpfulness of care are also important to consider (Boulter & Rickwood, 2013; Lindsay, Chambers, Pohle, Beall, & Lucksted, 2013). On top of these, the stress associated with lower income status, negative life events, family stress, and difficult living circumstances further decrease the likelihood of racial/ethnic minority families using treatment services (Williams et al., 2010).

Study Strength and Limitations

Methodological strengths of this study include (1) an innovative sampling strategy that directly recruited typically hard-to-engage ethnic minority youth with significant unmet behavioral health needs, (2) collection of multidimensional diagnostic-based perceived need data from both adolescents and caregivers, and (3) findings that are generalizable to the larger population of urban ethnic minority youth with unmet treatment needs, which encompasses the vast majority of inner-city youth with clinical disorders. In addition, the incorporation of linkage to appropriate behavioral services and tracking of engagement in treatment are valuable additions to the literature base on help-seeking, which to date, primarily relies on either retrospective studies or those that ask youth what they would do if they needed help in the future. This study attempted to building on existing literature by breaking down the help-seeking pathway to adolescent treatment in order to gain a better understanding of factors that facilitate and hinder behavioral service initiation.

Despite these strengths, a number of limitations warrant mention. First, although this study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of perceived need for treatment and engagement in treatment, there may be other, unmeasured constructs that account for some of the variance in these outcomes. In particular, measures of attitudes, beliefs, and stigma about mental illness or behavioral health treatment may strengthen future studies that aim to assess treatment seeking and attendance. To date, research examining the effect of beliefs about mental illness and associated stigma on treatment seeking and adherence has found that stigma and inaccuracies in knowledge about mental illness are associated with less treatment seeking (Pescosolido et al., 2007) and treatment non-adherence (Corrigan, 2004; Sirey et al., 2001), even over and above gender, race, and sociodemographic effects (Pescosolido, Perry, Martin, McLeod, & Jensen, 2007), but the strength of these relationships differ based on type of mental health problem (Angermeyer & Dietrich, 2006). In addition, findings do not address motivations for treatment attendance or barriers to treatment seeking or retention. Inclusion of these factors in future research may shed additional light on the high proportion of ethnic minority youth with persisting unmet treatment needs.

Second, while the demographics of the study sample are highly representative of populations from which referrals were solicited, selection biases were undoubtedly at play. Of referred families, those who were unable to be reached by research staff (32%) and those who refused to participate (20%) skewed toward being younger, non-school referred, and male. In addition, it is possible that youth from these uncontacted and refusing families had significantly differing levels of behavioral health problems, perceived need for treatment, and social capital. Third, adolescents who met diagnostic criteria for an internalizing disorder, but not an eligibility-determining externalizing or substance use disorder, were excluded from the randomized trial and thus are not represented in the study sample. Future studies of adolescents with unmet treatment needs may yield somewhat different perceived need results if they elect to use samples of adolescents with only internalizing disorders. Finally, the linkage procedures, which were determined to be essential for helping as many families as possible engage in treatment, may have impaired the capacity to study the natural course of treatment engagement for this sample, and thus the capacity to ascertain how various factors, including perceived need for treatment, might impact the “natural” engagement process.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Policy

Findings from this study can inform policy and practices of engaging minority adolescents with unmet treatment needs in the treatment-seeking process in several ways. Because adolescents tend to seek treatment for external concerns, rather than behavioral symptoms, family issues (e.g. conflict, cohesion, and functioning) may be optimal targets for motivational interventions designed to promote treatment readiness for youth. Indeed, study findings indicate that adolescents who perceive a need for treatment are likely to perceive the family environment as particularly stressful. By focusing on family issues, (a) gateway providers (e.g., caregivers, guidance counselors) may be more successful in demonstrating treatment needs to youth and connecting them with treatment and (b) treatment providers will likely be more successful in establishing rapport, alliance, and treatment plans. Treatment providers may gain additional traction by providing education regarding the nature and prevalence of behavior problems early in the treatment process, given that study findings indicated that clinical factors did not play a role in predicting perceived need among this sample.

Given the lack of concordance in perceived need between adolescents and their caregivers and their different predictors of perceived need, therapists working with adolescents should consider assessing and highlighting these potentially differing perceptions of presenting problems to assist with treatment planning, retention, and improved clinical and family outcomes. It may be that changes at the agency and therapist level can improve service delivery to this population, despite differing perceptions of treatment need among family members. Findings from this study indicate that linkage to treatment remains important throughout the clinical intake process and early in treatment. Beyond this initial support, more intensive outreach between visits, including reminders about upcoming sessions via telephone, e-mail, and text message to both caregivers and youth, may be beneficial. Other studies show that treatment engagement interventions focused on the complex array of barriers to starting and staying in treatment greatly influence attrition (Becker et al., 2015).

Many impoverished urban communities demonstrate mistrust of outsiders, including providers of mental health services; therefore, therapists’ cultural competence is an integral part of effectively working with this population (Huey, Tilley, Jones, & Smith, 2014). In particular, implementation of agency-wide trainings on culture-specific barriers to treatment and cultural perspectives on mental healthcare may help therapists and administrators work with and engage families during the intake process. In addition, collaborative research efforts between consumers from these communities and researchers hold considerable promise for addressing issues such as creating alliances, increasing relevance of services, and combating barriers to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA019607).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Jacqueline Fisher declares that she has no conflict of interest. Emily Lichvar declares that she has no conflict of interest. Aaron Hogue declares that he has no conflict of interest. Sarah Dauber declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Initial plans to operationalize treatment attendance as the number of treatment sessions attended were abandoned for a number of reasons. First, preliminary analyses indicated that these data were significantly skewed due to the large number of families who attended very few treatment sessions. Second, prior research has highlighted the lack of validity of such an operationalization due to variability in treatment program requirements regarding the number of treatment sessions to reach completion (Gopalan et al., 2010; Johnson, Mellor, & Brann, 2008). We determined that we could not account for this variability given the range of presenting problems among study participants and treatment modalities across the different clinics.

Contributor Information

Jacqueline Horan Fisher, Research Scientist, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse

Emily Lichvar, Public Health Advisor, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Aaron Hogue, Director, Adolescent and Family Research, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse

Sarah Dauber, Associate Director, Adolescent and Family Research, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse

References

- Abdullah T, Brown TL. Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(6):934–948. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self Report. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L. Advances in empirically based assessment: Revised cross-informant syndromes and new DSM-oriented scales for the CBCL, YSR, and TRF. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Howell CT, McConaughy SH, Stanger C. Six-year predictors of problems in a national sample of children and youth: II. Signs of disturbance. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:488–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Lin JY, Green JG, Sampson NA, Gruber MJ, Kessler RC. Role of referrals in mental health service disparities for racial and ethnic minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(7):703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Vallas M, Pumariega AJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;19(4):759–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre PK, Dowling K, Stephens RM, Laris AS, Rely K. Predictors of outpatient mental health service use by American youth. Psychological Services. 2008;5:251–261. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.5.3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Medical Care. 2008;46(7):647–653. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817a835d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LH, Alonso J, Mneimneh Z, Wells JE, Al-Hamzawi A, Borges G, Florescu S. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44(06):1303–1317. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S. Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: A review of population studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113(3):163–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Erkanli A, Farmer EM, Fairbank JA, Burns BJ, Keeler G, Costello EJ. Psychiatric disorder, impairment, and service use in rural African American and White youth. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:893–901. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. American Psychologist. 1999;54(5):317–326. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.5.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescence and emerging adulthood. New York, NY, USA: Pearson Education Limited; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: A systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho-Social-Medicine. 2012;9:1–15. doi: 10.3205/psm000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Lee BR, Daleiden EL, Lindsey M, Brandt NE, Chorpita BF. The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(1):30–43. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.814543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter E, Rickwood D. Parents’ experience of seeking help for children with mental health problems. Advances in Mental Health. 2013;11(2):131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brannan AM, Heflinger CA, Foster EM. The role of caregiver strain and other family variables in determining children’s use of mental health services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003;11:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, Tweed D, Stangl D, Farmer EM, Erkanli A. Children’s mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs. 1995;14(3):147–159. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TC, Lo CC. Mental health service and drug treatment utilization: Adolescents with substance use/mental disorders and dual diagnosis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2010;19:447–460. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B, Daleiden E, Ebesutani C, Young J, Becker K, Smith RL. Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18:154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Druss BG, Perlick DA. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2014;15(2):37–70. doi: 10.1177/1529100614531398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, He JP, Sampson NA, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Services for adolescents with psychiatric disorders: 12-month data from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(3):359–366. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakof GA, Tejeda M, Liddle HA. Predictors of engagement in adolescent drug abuse treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:274–281. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauber S, Hogue A. Profiles of systems involvement in a sample of high-risk urban adolescents with unmet treatment needs. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(10):2018–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Sorensen JR. Disproportionate minority confinement of juveniles: A national examination of Black-White disparity in placements, 1997–2006. Crime & Delinquency. 2013;59(1):115–139. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DA, Burgers DE, Rabinowitz J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 2015;141(4):858–900. doi: 10.1037/a0038498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RA, Falzer PR, Chapman J, Borum R. Mental illness, violence risk, and race in juvenile detention: Implications for disproportionate minority contact. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(1):32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle R, Mick E, Biederman J. Convergence between the Achenbach youth self-report and structured diagnostic interview diagnoses in ADHD and non-ADHD youth. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(4):350–352. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253732.79172.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Ford JD. Correlates of mental health service use intensity in the National Comorbidity Survey and National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1108–1115. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.8.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisher AJ, Kramer RA, Grosser RC, Alegria M, Bird HR, Bourdon KH, Narrow WE. Correlates of unmet need for mental health services by children and adolescents. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(5):1145–1154. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedenthal S. Racial disparities in mental health service use by adolescents who thought about or attempted suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37:22–34. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL, Landsverk JA. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1336–1343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Goldstein L, Klingenstein K, Sicher C, Blake C, McKay MM. Engaging families into child mental health treatment: Updates and special considerations. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry/Journal de l’Académie canadienne de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent. 2010;19(3):182–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):113–121. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S. Diagnostic profiles among urban adolescents with unmet treatment needs: Comorbidity and perceived need for treatment. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2011;12(1):18–32. doi: 10.1177/1063426611407500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Lichvar E, Spiewak G. Adolescent and caregiver reports of ADHD symptoms among inner-city youth: Agreement, perceived need for treatment, and behavioral correlates. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2014;18:212–225. doi: 10.1177/1087054712443160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Henderson CE, Bobek M, Johnson C, Lichvar E, Morgenstern J. Randomized trial of family therapy versus nonfamily treatment for adolescent behavior problems in usual care. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(6):954–969. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.963857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel KA, Odell S, Sander E, Baldassano RN, Barg FK. Treatment adherence in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease: Perceptions from adolescent patients and their families. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2011;19(1):80–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Jr, Tilley JL, Jones EO, Smith CA. The contribution of cultural competence to evidence-based care for ethnically diverse populations. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:305–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM. Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(5):629–645. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E, Mellor D, Brann P. Differences in dropout between diagnoses in child and adolescent mental health services. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;13(4):515–530. doi: 10.1177/1359104508096767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka S, Zhang L, Wells K. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf PJ, Alegria M, Cohen P, Goodman SH, Horwitz SM, Hoven CW, Regier DA. Mental Health service use in the community and schools: Results from the four-community MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:889–897. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon GD, Melnick G, Kressel D, Jainchill N. Circumstances, motivation, readiness, and suitability (the CMRS scales): Predicting retention in therapeutic community treatment. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1994;20(4):495–515. doi: 10.3109/00952999409109186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Liebenberg L, Ungar M. Understanding service provision and utilization for vulnerable youth: Evidence from multiple informants. Children and Youth Services Review. 2015;56:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey MA, Chambers K, Pohle C, Beall P, Lucksted A. Understanding the behavioral determinants of mental health service use by urban, under-resourced Black youth: Adolescent and caregiver perspectives. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22(1):107–121. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9668-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis J. What’s to know about hypothetical bias in stated preference valuation studies? Journal of Economic Surveys. 2011;25(2):363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Goldstein AS. Substance use and related behaviors among suburban late adolescents: The importance of perceived parent containment. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:591–614. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrast L, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care for children and young adults: A national study. International Journal of Health Services. 2016;46(4):810–824. doi: 10.1177/0020731416662736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:905–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Lynn CJ, Bannon WM. Understanding inner city child mental health need and trauma exposure: Implications for preparing urban service providers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(2):201. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):75–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, Olfson M. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D. CONSORT: An evolving tool to help improve the quality of reports of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1998;279(18):1489–1491. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R. Americans’ attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking: 1990–2003. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(5):642–651. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, Jin R, Druss B, Wang PS, Kessler RC. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(08):1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Family Environment Scale Manual: Development, Applications, Research - Third Edition. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Farrington DP. Risk factors for conduct disorder and delinquency: Key findings from longitudinal studies. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;55(10):633–642. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186(4):297–301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, Schlesinger HJ. Ethnicity and the use of outpatient health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:222–226. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer DL, Osborn P, King PS, Berg CA, Butler J, Butner J, Wiebe DJ. The structure of parental involvement and relations to disease management for youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;36(5):596–605. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Perry BL, Martin JK, McLeod JD, Jensen PS. Stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs about treatment and psychiatric medications for children with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(5):613–618. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: Assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Services Research. 1998;33:571–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumariega AJ, Glover S, Holzer CE, Nguyen H. II. Utilization of mental health services in a tri-ethnic sample of adolescents. Community Mental Health Journal. 1998;34:145–156. doi: 10.1023/a:1018788901831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(2):330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider WJ, Cavell TA, Hughes JN. A sense of containment: Potential moderator of the relation between parenting practices and children’s externalizing behaviors. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:95–117. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl KA, Offer D, Howard KI. Seeking help from informal and formal resources during adolescence: Sociodemographic and psychological correlates. Adolescent Psychiatry: Developmental and Clinical Studies. 2013;20:165–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Raue P, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(3):479–481. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Janavs J, Baker R, Harnett-Sheehan K, Knapp E, Sheehan M, Bonora LI. MINI-Mini International neuropsychiatric interview- English version 5.0. 0-DSM-IV. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheidow AJ, Henry DB, Tolan PH, Strachan MK. The role of stress exposure and family functioning in internalizing outcomes of urban families. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23(8):1351–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9793-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solorio M, Milburn N, Andersen R, Trifskin S, Rodríguez M. Emotional distress and mental health service use among urban homeless adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2006;33:381–393. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Accornero VH, Crum RM. Profiles of current disruptive behaviors and substance use among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:249–264. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis R, Toolis EE. Parenting across cultural contexts in the USA: Assessing parenting behaviour in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample. Early Child Development and Care. 2010;180(7):849–867. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM. Evidence-based youth psychotherapies versus usual clinical care: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. American Psychologist. 2006;61:671–689. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CD, Lindsey M, Joe S. Parent-adolescent concordance on perceived need for mental health services and its impact on service use. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:2253–2260. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186(1):69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Hoven CW, Cohen P, Liu X, Moore RE, Tiet Q, Bird HR. Factors associated with use of mental health services for depression by children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:189–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]