Abstract

Objective

Although life-threatening cardiac complications in influenza infection are rare, subclinical influenza-associated cardiac abnormalities may occur more frequently. We investigated the prevalence of subclinical cardiac findings.

Methods

After obtaining their written informed consent, 102 subjects were enrolled in the present study. The study subjects underwent a first set of examinations, which included electrocardiography (ECG), echocardiography, and the measurement of their cardiac enzyme levels. Those with one or more abnormal findings among these examinations were encouraged to undergo a repeat examination 2 weeks later.

Results

Among the 102 subjects enrolled, 22 (21.6%) were judged to have cardiac findings, including ST-T abnormalities, pericardial effusion, diastolic dysfunction, and cardiac enzyme elevation. Eighteen of these 20 subjects underwent a second screening at a median of 14 days later, and it was found that 11 of the 18 subjects were free from cardiac findings on this second examination. This suggested that the abnormalities were only transient and they therefore might have been associated with influenza. Approximately 20% of the influenza patients enrolled had cardiac findings, including ST-T segment abnormalities, pericardial effusion, and cardiac enzyme elevation.

Conclusion

Among the 102 patients who were studied, the cardiac findings were only mild and transient; however, physicians should be aware of influenza infection-associated cardiac abnormalities because such abnormalities may not be rare.

Keywords: influenza infection, cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, subclinical injury

Introduction

Myocarditis can be induced by various viruses, including adenovirus, enterovirus, and cytomegalovirus, and can sometimes be life-threatening (1-3). Among the extra-pulmonary complications of influenza infection, the recognition of myocarditis, as well as encephalitis, is critical because either condition can lead to a life-threatening outcome (4-8). Although clinically apparent influenza-associated myocarditis is rare (9,10), the mortality rate among patients with fulminant myocarditis is reported to be as high as 39-83% (11,12). Given that influenza virus infection can now be rapidly diagnosed and that several anti-influenza antiviral drugs are available that may potently ameliorate influenza-associated myocardial damage (13-15), the possibility of potential myocardial injury should not be overlooked among patients with flu-like symptoms.

In addition to fulminant myocarditis, previous studies have shown that influenza-associated cardiac injury may manifest as ECG abnormalities (16,17), elevation of cardiac enzymes (18-20), and left ventricular (LV) wall motion abnormalities (21), which may be accompanied by only slight symptoms (or be asymptomatic); however, the exact incidence of such clinically non-significant cardiac damage may depend on the types and extensiveness of the cardiac screening (14,22,23). In the present study, we prospectively investigated the incidence of subclinical cardiac abnormalities by ECG, echocardiography, and the laboratory measurement of cardiac enzyme levels among patients with proven influenza virus infection.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Osaka Medical College, and written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants before their enrollment. Between February 2014 and March 2017, 102 adults suffering from influenza infection were recruited for this study. The diagnosis of influenza infection (either type A or B) was confirmed based on a positive nasal swab specimen and was made using a commercially available test kit, such as the QuickNavi-Ful kit (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan).

Cardiac examination

The first and - when necessary - second examination, included 12-lead ECG, echocardiography, and the measurement of the patient's cardiac enzyme levels. With regard to ECG findings, ST-T abnormalities, ventricular/supraventricular premature contractions, atrioventricular and intraventricular block, high voltages, and other arrhythmia or conduction disturbances were regarded as abnormal. For echocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography was performed with commercially available ultrasound machines and phased array probes (Vivid 7 Dimension and Vivid E9; GE-Vingmed, Horten, Norway).

The LV ejection fraction was calculated in the apical 4- and 2-chamber views by the modified Simpson's method. To assess the LV diastolic function, the systolic (s') and early diastolic (e') annular velocities on the septal and lateral sides were measured by pulsed Doppler. Subjects who had an e' value of >1 standard deviation lower than the mean of the age-matched population, as determined in a previous study (11), were considered to have an impaired diastolic function. Regarding cardiac enzymes, CKMB (normal range, 7-15 U/L) and cardiac troponin T (normal range, <0.014 ng/mL) were measured.

Study protocol

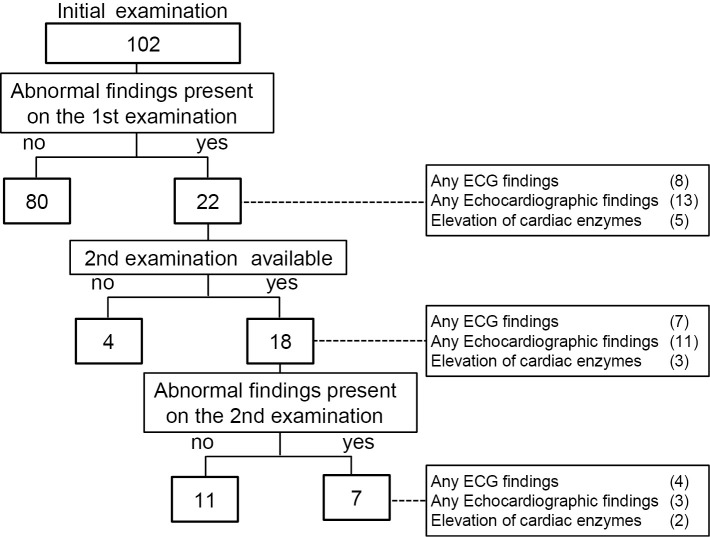

Soon after the patients were allowed to go back work, which was in general more than a couple of days after the alleviation of fever, the subjects visited our outpatient service to undergo the initial cardiac screening examination, which consisted of ECG, echocardiography, and the abovementioned laboratory investigations. Those who had one or more of the following findings on the first examination were considered to have cardiac abnormalities and were advised to undergo a second (repeat) examination two weeks later: 1) any ECG abnormalities; 2) a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of <50%; 3) the presence of pericardial effusion; 4) reduced mitral annular velocity (a marker of diastolic dysfunction); or 5) increased cardiac enzymes (CKMB or cardiac troponin T). The second examination was performed at a median of 14 days (range 10-35 days) after the first examination (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A flow chart showing the analysis of the patients undergoing the first and second examinations to detect cardiac abnormalities.

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, and as the number (percentage) for categorical variables. The unpaired Student's t-test was used for group comparisons. Where applicable, clinical and echocardiographic parameters were compared between the first and second examinations by a paired t-test. Categorical parameters were compared by a χ2 test. p values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

The patients were 23 to 62 years of age and >90% of the participants were infected with type A influenza virus (Table 1). None of the subjects had known preceding cardiovascular disorders. All of them had received a seasonal influenza vaccination before the indexed influenza infection, and 99 subjects had taken anti-influenza antivirus medication after the diagnosis of influenza infection.

Table 1.

The Patient Characteristics.

| Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 37.6±10.7 | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 28 | (27.5) |

| Heart rate, bpm | 66.4±11.9 | |

| Known accompanying disorders | ||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 3 | (2.9) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1 | (1.0) |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 2 | (2.0) |

| Influenza vaccination n (%) | 102 | (100.0) |

| Influenza season | ||

| 2013-2014 | 21 | (20.6) |

| 2015-2016 | 38 | (37.3) |

| 2016-2017 | 43 | (42.2) |

| Type of virus infected | ||

| Type A, n (%) | 93 | (91.2) |

| Type B, n (%) | 9 | (8.8) |

| Anti-influenza drug used | ||

| Laninamivir, n (%) | 64 | (62.7) |

| Oseltamivir, n (%) | 27 | (26.5) |

| Zanamivir, n (%) | 4 | (3.9) |

| Peramivir, n (%) | 4 | (3.9) |

| Non-use, n (%) | 3 | (2.9) |

| Any ECG findings, n (%) | 8 | (7.8) |

| ST-segment elevation, n (%) | 2 | (2.0) |

| ST-segment depression n (%) | 1 | (1.0) |

| T wave flattening, n (%) | 1 | (1.0) |

| Premature atrial contraction, n (%) | 2 | (2.0) |

| Premature ventricular contraction, n (%) | 1 | (1.0) |

| Right-bundle branch block, n (%) | 1 | (1.0) |

| Left-bundle branch block, n (%) | 0 | (0.0) |

| High voltage, n (%) | 2 | (2.0) |

| Any echocardiographic findings, n (%) | 13 | (12.7) |

| Pericardial effusion, n (%) | 2 | (2.0) |

| Decreased e’, n (%) | 11 | (10.8) |

| Low LVEF, n (%) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Elevation of cardiac enzymes | 5 | (4.9) |

| Elevated CKMB, n (%) | 5 | (4.9) |

| Elevated cardiac troponin T, n (%) | 0 | (0.0) |

The prevalence of abnormalities in the ECG, laboratory, and echocardiography findings

Among a total of 102 subjects, 22 (21.6%) had one or more cardiac abnormalities on the initial cardiac examination (Fig. 1, Table 1). ECG abnormalities, including ST-segment elevation/depression, T wave flattening, premature contraction, and right bundle branch block, were noted in 8 subjects. Two subjects showed pericardial effusion and decreased e', but no subjects showed a decreased LVEF (<50%). The type of influenza virus infection in both subjects with pericardial effusion was type A. With regard to the cardiac enzyme levels, CKMB was increased (median, 17 IU/mL; range 16-36 IU/mL) in 5 subjects; no subjects had an elevated cardiac troponin T concentration. Five patients had a CKMB level of >15 U/L; subjects with a CKMB level of 36 U/L, 20 U/L, 17 U/L, and 16 U/L had a CKMB-to-total CK ratio of 53%, 4%, 21%, 13%, and 30%, respectively; thus, there might have been some subjects who experienced skeletal muscle involvement. In a 60-year-old man who had a history of hypertension and anti-hypertensive treatment, the interventricular wall thickness and posterior wall thickness were thickened to 15 mm and 13 mm, respectively. However, we did not regard this myocardial thickening as the result of myocardial inflammation as these were not findings suggestive of myocarditis (i.e., pericardial effusion, elevation of cardiac enzymes, and ST-T segment abnormalities).

A comparison of patients with and without cardiac abnormalities on the first examination, revealed that those with cardiac findings were significantly older, but there were no differences in terms of gender, influenza season, type of influenza virus, or the anti-influenza antiviral drug that was used (Table 2). Among the patients who had no heart-related abnormalities (n=80) the size of the echocardiography-measured inferior vena cava in patients with no abnormalities was 1.70±0.5 mm on the inspiratory phase, while the size of the echocardiography-measured inferior vena cava in patients with some abnormalities (n=22) was 1.56±0.5 mm (p=0.210). On the expiratory phase, the size of the inferior vena cava in patients with no abnormalities was 0.64±0.29 mm, while that in patients with some abnormalities was 0.65±0.27 mm (p=0.894).

Table 2.

The Characteristics of the Patients with and without Cardiac Findings on the First Examination.

| Cardiac findings (-) (n=80) |

Cardiac findings (+) (n=22) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 36.5±9.9 | 41.6±12.6 | 0.045 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 21 (26.3) | 7 (31.8) | 0.604 |

| Influenza season | |||

| 2013-2014 | 17 (21.3) | 4 (18.2) | 0.668 |

| 2015-2016 | 28 (35.0) | 10 (45.5) | |

| 2016-2017 | 35 (43.8) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Type of virus | |||

| Type A, n (%) | 75 (93.8) | 18 (81.8) | 0.081 |

| Type B, n (%) | 5 (6.3) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Anti-influenza drug used | |||

| Laninamivir, n (%) | 48 (60.0) | 16 (72.7) | 0.551 |

| Oseltamivir, n (%) | 22 (27.5) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Zanamivir, n (%) | 4 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Peramivir, n (%) | 4 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Non-use, n (%) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (4.5) |

Second examination

Among the 22 subjects with one or more cardiac abnormalities on the first examination, 18 underwent a second examination (Fig. 1). The reasons why the remaining four patients did not undergo the second examination were unclear. Among these 18 subjects, the heart rate on the first examination (64±13 bpm) did not differ significantly from that on the second examination (67±8 bpm, p=0.35).

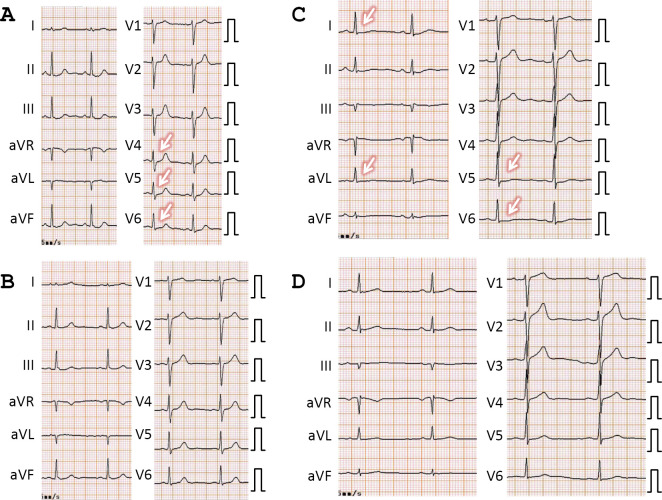

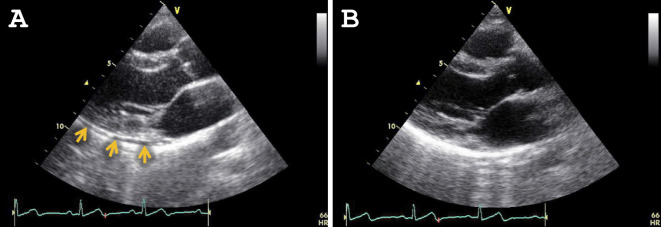

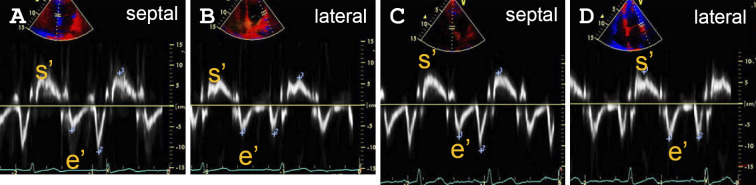

Cardiac findings were only noted in 7 of the 18 subjects undergoing the second examination, indicating that the finding on the first examination had been resolved in 11 patients. For example, ST-segment depression in a 48-year-old woman (Fig. 2A and B), and ST segment depression and T-wave flattening in a 40-year-old man, which were observed on the first examination (Fig. 2C and D), were ameliorated on the second examination. In addition, the pericardial effusion noted on the initial echocardiography had disappeared on the second for one subject (Fig. 3). Fig. 4 shows the s' and e' velocities on Doppler imaging of a 60-year-old woman. In comparison to the first examination (Fig. 4A and B), both the s' and e' waves had increased in velocity on the second examination (Fig. 4C and D), suggesting an improvement of the LV diastolic function.

Figure 2.

The changes on electrocardiography (ECG). A, B: The ECG findings from the first (A) and the second (B) examinations of a 48-year-old woman. A: Slight ST-segment depression was noted in leads II, III, aVF, V4, V5, and V6 (arrows) on the first examination. B: These abnormalities had disappeared on the second examination. C, D: The ECG tracings from the first (C) and second (D) examinations of a 40-year-old man. C: Slight ST-T segment depression and T-wave flattening were noted on the first examination (arrows). D: These abnormalities were ameliorated on the second examination.

Figure 3.

Echocardiographic findings. The echocardiographic findings from the first (A) and the second (B) examinations of a 33-year-old woman. A: A small amount of pericardial effusion was noted around the posterior side of the left ventriculum (arrows). B: Effusion was not present on the second examination.

Figure 4.

The mitral annular velocity profiles with tissue Doppler imaging. Systolic (s’) and early diastolic (e’) velocities on tissue Doppler imaging on the first (A, B) and second (C, D) examinations of a 60-year-old woman. A, C: The septal wall side. B, D: The lateral wall side. Both s’ and e’ waves showed increased velocity on the second examination, which was suggestive of the amelioration of the diastolic function.

No significant differences were observed in age, gender prevalence, type of virus, influenza season, or antiviral medication received (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Characteristics of the Subjects with and without Cardiac Findings on the Second Examination.

| Cardiac findings (-) (n=11) |

Cardiac findings (+) (n=7) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.0±13.0 | 41.4±13.8 | 0.930 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 1 (9.1) | 4 (57.1) | 0.026 |

| Influenza season | |||

| 2013-2014 | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.267 |

| 2015-2016 | 4 (36.4) | 5 (71.4) | |

| 2016-2017 | 5 (45.5) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Type of virus | |||

| Type A, n (%) | 8 (72.7) | 6 (85.7) | 0.267 |

| Type B, n (%) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Anti-influenza drug used | |||

| Laninamivir, n (%) | 9 (81.8) | 4 (57.1) | 0.343 |

| Oseltamivir, n (%) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Zanamivir, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Peramivir, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Non-use, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) |

Discussion

In the present study, we examined 102 subjects who were suffering from influenza infection to investigate whether they experienced any cardiac abnormalities. According to the study criteria, 22 (21.6%) patients were evaluated to have certain abnormal cardiac findings. Furthermore, among the 18 subjects who underwent a second examination, 11 patients had no cardiac abnormalities, indicating that at least 11 (10.8%) of the 102 subjects had transient cardiac abnormal findings after influenza virus infection.

Several previous studies have addressed the incidence of cardiac abnormalities among patients with influenza infection. In 1959, Gibson et al. reported that ECG abnormalities were found in 29% of patients (16,17). In a clinicopathological study of 42 patients who were treated at home during the 1972-1973 A2 England influenza epidemic, Verel et al. reported that 18 patients showed transient ECG changes, including ST-segment deviation, T-wave inversion, flattening of the T wave, sinus bradycardia, sinus tachycardia, nodal rhythm, and atrial fibrillation (17). These findings are consistent with the notion that influenza virus infection may be an underlying cause of mild myocarditis, which is diagnosed based on serial ECG changes during an acute infection (24).

The frequency of elevated cardiac enzyme levels among subjects infected with influenza virus has been reported in several previous studies. For example, Karjalainen et al. reported that, among 41 patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms and serological evidence of influenza infection, 6 (15%) had evidence of myocarditis and 3 (7.1%) showed increased CK-MB levels (18). In contrast, Ison et al. demonstrated that among 30 healthy young adults without known cardiovascular disease and with a positive influenza antigen test, no patients with ECG changes had elevated serum troponin levels or decreased LVEF (16). In addition, Greaves et al. analyzed 152 patients with influenza infection and found that CK was elevated in some patients; however, none of them had increased cardiac troponin T or I levels (20). They concluded that skeletal muscle injury is relatively common, whereas myocardial inflammation - if present - is likely to be rare among patients with influenza infection (20). In the present study, although 5 patients showed increased CKMB (>15 U/L) levels, the maximum CKMB was only 36 U/L and no patients showed increased cardiac troponin T; thus, in the present study population, the myocardial damage - if present - was considered to be minimal. This was in agreement with the studies of Ison et al. and Greaves et al.

Ison et al. also demonstrated abnormal ECG findings in 53%, 33%, 27%, and 23% of patients on days 1, 4, 11, and 28 after the onset of infections (16). In general, the cardiac manifestations of influenza virus infection - when present - become apparent at 4 to 9 days after the onset of flu symptoms (25); however, the study of Ison et al. suggested that ECG abnormalities might be already present at an earlier time-point after the onset of infection. We did not attempt to obtain ECG data at an earlier time point in the present study in order to avoid the unnecessary spread of influenza infection to the medical staff; however, we should be aware of the possibility of a higher prevalence of ECG abnormalities at an earlier time point during the course of infection. It should also be noted that influenza-associated cardiac dysfunction-related symptoms frequently occur between 4 and 7 days after the initial symptoms of viral infection (26).

In the present study, pericardial effusion was observed in two subjects, and was confirmed to be transient in one of these subjects at follow-up. Although the pathogenesis of pericardial effusion in the setting of myocardial viral infection is unclear, various viruses may induce pericardial effusion (27). There are few reports on influenza virus-associated pericardial effusion (28,29); nevertheless, it may lead to cardiac tamponade and a fatal outcome (25). The present study indicated that influenza virus-associated pericarditis may occur in approximately 2% of patients with influenza infection; thus, we should pay attention to this pathology.

Although we did not investigate the mechanisms through which influenza infection causes myocardial injury in the present study, a number of mechanisms may be involved. For example, the alterations of the electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings may reflect the impairment of intracellular calcium handling (21), which may be aggravated by the activation or the enhanced release of various inflammatory cytokines, or by transient hypoxia-induced mitochondrial dysfunction (30).

The present study is associated with several limitations. First, the number of patients enrolled was relatively small. Cardiac complications, if present, might differ according to the type of influenza virus and the anti-influenza treatment received; these possibilities should be analyzed in future studies. Second, in most cases, cardiac data were not available from the time before the onset of influenza infection; thus, we could not definitely determine whether any cardiac abnormalities were present beforehand, or whether such findings were associated with influenza infection when they disappeared on the second examination. Third, in the present study, patients who underwent the second examination had certain cardiac abnormalities that were detected on the first examination; thus, we do not know whether there were any subjects who might have shown abnormal findings on the second examination but not on the first examination. Fourth, we did not encourage the patients without cardiac abnormalities to undergo a second examination; thus, we could not determine whether they were free from any cardiac abnormalities at a more delayed time point. Last, the possibility remains that vaccination for seasonal influenza (31) or other unidentified factors influenced the cardiac abnormalities that were observed in the study.

In conclusion, among 102 subjects who were diagnosed with influenza (type A, n=93; type B, n=9), 22 (21.6%) were considered to have abnormal cardiac findings. Among 18 subjects with cardiac findings on the first examination who underwent a second examination, cardiac findings were only noted in 7 subjects, suggesting that transient subclinical cardiac findings may not be a rare occurrence among Japanese subjects infected with influenza virus. Considering that viral myocarditis is still associated with a high rate of mortality (32), physicians should not overlook cardiac findings among subjects with flu-like symptoms; however, influenza-associated cardiac abnormalities are usually subclinical and/or transient, as was shown in the present study.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Financial Support

This work was supported in part by Grants in Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (No. 15K09588).

Acknowledgement

We are highly appreciative of Megumi Hashimoto, Hitomi Iwai, Fusako Maeda, and Junko Nakamura for their excellent assistance.

References

- 1. Rose NR. Viral myocarditis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 28: 383-389, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yajima T. Viral myocarditis: potential defense mechanisms within the cardiomyocyte against virus infection. Future Microbiol 6: 551-566, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pollack A, Kontorovich AR, Fuster V, et al. Viral myocarditis--diagnosis, treatment options, and current controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol 12: 670-680, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sellers SA, Hagan R, Hayden F, et al. The hidden burden of influenza: a review of the extra-pulmonary complications of influenza infection. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 11: 372-393, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan K, Meek D, Chakravorty I. Unusual association of ST-T abnormalities, myocarditis and cardiomyopathy with H1N1 influenza in pregnancy: two case reports and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 5: 314, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar K, Guirgis M, Zieroth S, et al. Influenza myocarditis and myositis: case presentation and review of the literature. Can J Cardiol 27: 514-522, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Himmel F, Hunold P, Schunkert H, et al. Influenza A positive but H1N1 negative myocarditis in a patient coming from a high outbreak region of new influenza. Cardiol J 18: 441-445, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cabral M, Brito MJ, Conde M, et al. Fulminant myocarditis associated with pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus. Rev Port Cardiol 31: 517-520, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore DL, Vaudry W, Scheifele DW, et al. Surveillance for influenza admissions among children hospitalized in Canadian immunization monitoring program active centers, 2003-2004. Pediatrics 118: e610-e619, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nayman Alpat S, Usluer G, Ozgunes I, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza infection. Influenza Res Treat 2012: 603989, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saji T, Matsuura H, Hasegawa K, et al. Comparison of the clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome of fulminant and acute myocarditis in children. Circ J 76: 1222-1228, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ukimura A, Izumi T, Matsumori A. A national survey on myocarditis associated with the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in Japan. Circ J 74: 2193-2199, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baik SH, Jeong HS, Kim SJ, et al. A case of influenza associated fulminant myocarditis successfully treated with intravenous peramivir. Infect Chemother 47: 272-277, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoshimizu N, Tominaga T, Ito T, et al. Repetitive fulminant influenza myocarditis requiring the use of circulatory assist devices. Intern Med 53: 109-114, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Warren-Gash C, Smeeth L, Hayward AC. Influenza as a trigger for acute myocardial infarction or death from cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 9: 601-610, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ison MG, Campbell V, Rembold C, et al. Cardiac findings during uncomplicated acute influenza in ambulatory adults. Clin Infect Dis 40: 415-422, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verel D, Warrack AJ, Potter CW, et al. Observations on the A2 England influenza epidemic: a clinicopathological study. Am Heart J 92: 290-296, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karjalainen J, Nieminen MS, Heikkila J. Influenza A1 myocarditis in conscripts. Acta Med Scand 207: 27-30, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaji M, Kuno H, Turu T, et al. Elevated serum myosin light chain I in influenza patients. Intern Med 40: 594-597, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greaves K, Oxford JS, Price CP, et al. The prevalence of myocarditis and skeletal muscle injury during acute viral infection in adults: measurement of cardiac troponins I and T in 152 patients with acute influenza infection. Arch Intern Med 163: 165-168, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erden I, Erden EC, Ozhan H, et al. Echocardiographic manifestations of pandemic 2009 (H1N1) influenza a virus infection. J Infect 61: 60-65, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mamas MA, Fraser D, Neyses L. Cardiovascular manifestations associated with influenza virus infection. Int J Cardiol 130: 304-309, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibson TC, Arnold J, Craige E, et al. Electrocardiographic studies in Asian influenza. Am Heart J 57: 661-668, 1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karjalainen J, Heikkila J, Nieminen MS, et al. Etiology of mild acute infectious myocarditis. Relation to clinical features. Acta Med Scand 213: 65-73, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sidhu RS, Sharma A, Paterson ID, et al. Influenza H1N1 infection leading to cardiac tamponade in a previously healthy patient: a case report. Res Cardiovasc Med 5: e31546, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Onitsuka H, Imamura T, Miyamoto N, et al. Clinical manifestations of influenza a myocarditis during the influenza epidemic of winter 1998-1999. J Cardiol 37: 315-323, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sagrista-Sauleda J, Merce J, Permanyer-Miralda G, et al. Clinical clues to the causes of large pericardial effusions. Am J Med 109: 95-101, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Knezevic Pravecek M, Hadzibegovic I, Coha B, et al. Pericardial effusion complicating swine origin influenzae A (H1N1) infection in a 50-year-old woman. Med Glas (Zenica) 10: 173-176, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tseng GS, Hsieh CY, Hsu CT, et al. Myopericarditis and exertional rhabdomyolysis following an influenza A (H3N2) infection. BMC Infect Dis 13: 283, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hochstadt A, Meroz Y, Landesberg G. Myocardial dysfunction in severe sepsis and septic shock: more questions than answers? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 25: 526-535, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Engler RJ, Nelson MR, Collins LC Jr, et al. A prospective study of the incidence of myocarditis/pericarditis and new onset cardiac symptoms following smallpox and influenza vaccination. PLoS One 10: e0118283, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matsuura H, Ichida F, Saji T, et al. Clinical features of acute and fulminant myocarditis in children - 2nd Nationwide Survey by Japanese Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery. Circ J 80: 2362-2368, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]