Abstract

Aim: The purpose of this study was to investigate strain dependent differences of the cariogenic biofilm forming Streptococcus mutans within both simple and complex communities.

Methods: A mono-species containing representative S. mutans clinical isolates (caries and non-caries), and a multispecies in vitro caries biofilm model containing Lactobacillus casei, Veillonella dispar, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Actinomyces naeslundii, and either of two representative S. mutans clinical isolates (caries and non-caries), was developed as a comparison model. Compositional analysis of total and live bacteria within biofilms, and transcriptional analysis of biofilm associated virulence factors were evaluated by live/dead PCR and quantitative PCR, respectively. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to analyze the architecture of biofilm. One-way analysis of variance and t-tests were used to investigate significant differences between independent groups of data.

Results: Within a mono-species biofilm, different S. mutans strains responded similarly to one another during biofilm formation in different carbohydrate sources, with sucrose showing the highest levels of biofilm biomass and galactose showing the lowest. Within the polymicrobial biofilm system, compositional analysis of the bacteria within the biofilm showed that S. mutans derived from a caries-free patient was preferentially composed of both total and viable L. casei, whereas S. mutans derived from a caries patient was dominated by both total and viable S. mutans (p < 0.001). Normalized gene expression analysis of srtA, gtfB, ftf, spaP, gbpB, and luxS, showed a general upregulation within the S. mutans dominant biofilm.

Conclusion: We were able to demonstrate that individual strains derived from different patients exhibited altered biofilm characteristics, which were not obvious within a simple mono-species biofilm model. Influencing the environmental conditions changed the composition and functionality S. mutans within the polymicrobial biofilm. The biofilm model described herein provides a novel and reproducible method of assessing the impact on the biofilm microbiome upon different environmental influences.

Keywords: Streptococcus mutans, biofilm, polymicrobial, caries, models

Introduction

Streptococcus mutans has been reported as a primary cariogenic bacterial pathogen (Loesche, 1986). A key virulence attribute of S. mutans exists in its capacity to metabolize and process various sugar carbohydrates, and use these to form biofilms on the enamel surface of the tooth (Bowen and Koo, 2011). These biofilms are largely composed of bacterial microcolonies embedded in an extracellular polymeric matrix. The matrix prevents against mechanical removal and aids in defense against host protein interactions, additionally acting as a diffusion barrier from a range of natural and artificial antimicrobial agents (Senadheera and Cvitkovitch, 2008). The process of carbohydrate metabolism and development of the biofilm facilitates a disadvantage to the host. Environmental pH is driven down within the oral cavity leading to demineralization of hydroxyapatite, enamel dissolution, and ultimately carious lesions (Takahashi and Nyvad, 2008). However, this is a rather over simplistic viewpoint, despite the well-established multifactorial basis of this disease. Several studies have revealed that the level of S. mutans is not necessarily high in caries-associated biofilms, suggesting that the microbial basis of this disease is subtler, and yet more complicated at the same time. Indeed, the increasing acid environment facilitates increased proportions of different S. mutans genotypes and other acidogenic species (Napimoga et al., 2005). The interconnectedness of S. mutans biofilms and overall ecology within the oral environment is likely to play a critical role in driving disease phenotypes. Recent evidence suggests the presence of specific functional ecotypes with either a saccharolytic or proteolytic propensity may be the driving factors in oral biofilm diseases (Zaura et al., 2017).

S. mutans is a diverse species of bacteria, and this variety has the potential to influence adhesion, biofilm formation and associated virulence (Napimoga et al., 2005). Indeed, isolates of S. mutans are known to vary in a range of phenotypic properties (Lembo et al., 2007). Palmer and colleagues sequenced 57 geographically and genetically diverse isolates of S. mutans, where a high degree of variability in properties were observed between strains, including a broad spectrum of sensitivities to low pH, oxidative stress, and exposure to competence stimulating peptide (Palmer et al., 2013). Moreover, our previous study highlights the genotypic diversity of S. mutans isolates from children and indicates that S. mutans heterogeneity may correlate with caries susceptibility (Yu et al., 2015). These genotypic variations in adhesion, colonization and associated pathogenicity are thought to underlie the known individual variation in cariogenicity, though until now, attempts to correlate them with specific individual properties with caries in humans have been largely unsuccessful. Therefore, a significant research effort toward understanding the mechanisms of the development of mixed-species communities containing S. mutans, and defining their active role, are required. The advent of microbiome analysis has started to reveal the relative importance of different bacterial species within the community structure, though meta-transcriptomic approaches have been more informative in showing active participation. Indeed, recent reports suggest that S. mutans actively represented only 0.02–0.73% of the bacterial community in disease, exemplifying the polymicrobial nature of this disease (Simon-Soro et al., 2014). This further supports the ecological plaque hypothesis of dental caries, where the entire consortium of acidogenic/aciduric bacteria, not only the mutans streptococci, contributes to the caries process (Takahashi and Nyvad, 2011). The recent characterization of saccharolytic ecotypes in otherwise orally healthy individuals suggests our own functional microbiome plays a role in dictating whether or not we are caries susceptible (Zaura et al., 2017). To facilitate further understanding of these mechanisms, models capable of dissecting and elucidating biological processes with caries are necessary. Current models have limited biodiversity with a lack of representation of other species and genus; therefore are not representative of competing bacteria that may be present within a cariogenic state. To this end, the purpose of this study was to develop a suitable caries biofilm model that was able to recapitulate these aforementioned concepts, i.e., the biological diversity associated with S. mutans clinical isolates, and test how this translates within a simple mono-species and novel polymicrobial biofilm system.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Isolates of S. mutans used in this study were obtained from a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University (ERC-[2012]-13).

Assessing Mono-Species Biofilm Development of Clinical Isolates

A subset of S. mutans clinical strains isolated from children without caries were used for this study (Yu et al., 2015). S. mutans (n = 20) were selected to form the caries-free group, and S. mutans from children with a DMFT index of ≥6 (n = 105) were selected to form the caries group. All S. mutans clinical isolates were propagated on horse blood agar (E & O Laboratories Ltd., Bonnybridge, United Kingdom) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for purity plating, then single colonies incubated in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 prior to standardization to 1 × 107 cells/mL. S. mutans strains from the caries (n = 10) and caries-free (n = 10) isolates were then assessed for biofilm growth in different carbohydrate sources [sucrose, mannose, fructose, glucose and galactose (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom)] at 0.125, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5% (w/v) in BHI. Mono-species biofilms were grown in flat-bottomed 96-well microtiter plates at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. Following incubation, the supernatant was removed for pH testing using a pH microelectrode (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland), and the resultant biofilm biomass was quantified using a crystal violet (CV) stain, as described previously (Millhouse et al., 2014; Sherry et al., 2016). Briefly, biofilms were dried overnight at room temperature before staining with 0.05% (w/v) CV (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom) for 15 min. The stained biofilms were then washed with water to remove excess dye, then de-stained with 100% ethanol. The released dye was then quantified in a plate reader (FluoStar Omega, BMG Labtech) at 570 nm. To measure biofilm viability, AlamarBlue® (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) was added to PBS washed biofilms and incubated for 1 h in 1:10 AlamarBlue®:BHI media at 37°C in 5% CO2, prior to a color change being quantified on a plate reader at 570/600 nm, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Each biofilm was evaluated three times, and the mean recorded as pH values. All analysis was performed in triplicate on at least three separate occasions. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed on selected biofilms to visualize the effects of selected carbohydrates. Following biofilm development, cells were carefully washed with PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde, 0.15M sodium cacodylate, and 0.15% w/v Alcian Blue (pH 7.4), as previously described (Erlandsen et al., 2004). The specimens were sputter-coated with gold and viewed under a JEOL JSM-6400 scanning electron microscope. Images were assembled using Photoshop software (Adobe, San Jose, CA, United States).

Development of a Multi-Species Caries Biofilm Model

For multi-species biofilm model studies, a selection of laboratory strains commonly associated cariogenic bacterial species were used. These included Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC 10596, Veillonella dispar ATCC 27335, Actinomyces naeslundii ATCC 19039 and Lactobacillus casei DSMZ 20011. All procedures were carried out to BSL-2 safety requirements. Two S. mutans clinical isolates were also included (caries and non-caries) in comparison models. S. mutans and L. casei were maintained on Colombia blood agar [CBA; Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom] and MRS Agar (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom) at 37°C in 5% CO2, respectively. V. dispar, A. naeslundii and F. nucleatum were all maintained on fastidious anaerobic agar [FAA; Lab M Ltd., Lancashire, United Kingdom] under anaerobic conditions (85% N2, 10% CO2, and 5% H2, [Don Whitley Scientific Limited, Shipley, United Kingdom]). Overnight cultures of S. mutans and L. casei were grown for 24 h in BHI broth and MRS broth at 37°C in 5% CO2, respectively. Cultures of A. naeslundii and V. dispar were grown in BHI and F. nucleatum was cultured in Schaedler’s anaerobic broth [Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom], and all were incubated for 48 h anaerobically (85% N2, 10% CO2, and 5% H2). All bacterial cultures were standardized to a final concentration of 1 × 108 cells/mL by washing, centrifuging and resuspending in PBS.

A multi-species caries biofilm model was created by adopting a similar approach to our previously published studies (Millhouse et al., 2014; Sherry et al., 2016). Briefly, standardized S. mutans, L. casei, V. dispar, F. nucleatum, and A. naeslundii were diluted 1:10 to 1 × 107 cells/mL in artificial saliva (AS) containing either sucrose and galactose (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom) at a single defined concentration of 1% w/v, and added to a 24-well tissue culture plate (Corning, NY, United States) containing 13 mm2 × 1.5 mm thick hydroxyapatite coverslips (Plasma Biotal Ltd., Tideswell, Derbyshire, United Kingdom). The bacterial suspensions were then incubated statically at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 120 h, with spent supernatants being replaced with fresh AS every 24 h. Biofilms were then assessed for both biomass and viability, using CV and AlamarBlue® assays, respectively, as described above.

Compositional Analysis of Total and Live Bacteria Within Biofilms

To enumerate the viable and total number of cells from the biofilm a qPCR viability method was used, as previously described by our group (Sherry et al., 2016). Briefly, multi-species biofilms were prepared as described above, from 24 to 120 h, in sucrose and galactose. Resultant biofilms were gently washed in PBS prior to sonication from the HA surface at 35 kHz for 10 min. The sample was split into two equal homogenous suspensions and to one of these 50 μM of propidium monoazide (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom) was added prior to incubation for 10 min in the dark (viable cells). This was then exposed for 5 min to a 650 W halogen light. The remaining sample without the addition of propidium monoazide was used as controls to quantify the biomass (total cells). To extract the DNA the QIAmp mini DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, United Kingdom) was used, following the manufacturer’s instructions with the modification that the sonicate was incubated for 2.5 h to ensure cell lysis and the addition of mutanolysin (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom). Real-time quantitative (qPCR) was then performed to quantify the composition of biofilms in both the total and live only samples following treatment. For qPCR, 1 μL of extracted DNA was added to a mastermix containing 10 μL SYBR® GreenERTM, 7 μL UV-treated RNase-free water and 1 μL of 10 μM forward/reverse primers for each bacterial species. The primers used were previously published and are listed in Table 1. The thermal profile used consisted of an initial denaturation of 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 60 s at 55°C, and 60 s at 72°C. Three independent replicate using MxProP Quantitative PCR machine and MxPro 3000P software (Stratagene, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Samples were quantified to calculate the colony forming equivalent (CFE) based upon a standard curve methodology of bacterial colony forming units ranging from 1 × 104 to 108 CFU/mL. Melting curve analysis was performed for all primer sets to ensure a single peak, which was indicative of primer specificity.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used in this study.

| Target | Primer Sequence (5’-3’) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial species (16S rRNA) | ||

| Streptococcus spp. | F – GATACATAGCCGACCTGAG | Bernabé et al., 2016 |

| R – CCATTGCCGAAGATTCC | ||

| A. naeslundii | F – GGCTGCGATACCGTGAGG | Periasamy et al., 2009 |

| R – TCTGCGATTACTAGCGACTCC | ||

| F. nucleatum | F – GGATTTATTGGGCGTAAAGC | Bernabé et al., 2016 |

| R – GGCATTCCTACAAATATCTACGAA | ||

| V. dispar | F – CCGTGATGGGATGGAAACTGC | Periasamy et al., 2009 |

| R – CCTTCGCCACTGGTGTTCTTC | ||

| L. casei | F – TGCACTGAGATTCGACTTAA | Desai et al., 2006 |

| R – CCCACTGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT | ||

| S. mutans gene | ||

| spaP | F – TCCGCTTATACAGGTCAAGTTG | Bernabé et al., 2016 |

| R – GAGAAGCTACTGATAGAAGGGC | ||

| gbpB | F – CGTGTTTCGGCTATTCGTGAAG | Bernabé et al., 2016 |

| R – TGCTGCTTGATTTTCTTGTTGC | ||

| gtfB | F – AGCAATGCAGCCAATCTACAAAT | Bernabé et al., 2016 |

| R – TACGAACTTTGCCGTTATTGTCA | ||

| luxS | F – ACTGTTCCCCTTTTGGCTGTC | Bernabé et al., 2016 |

| R – AACTTGCTTTGATGACTGTGGC | ||

| srtA | F – GAAGCTTCCTGTAATTGGCG | Levesque et al., 2005 |

| R – TTCATCGTTCCAGCACCATA | ||

| Ftf | F – AAATATGAAGGCGGCTACAACGC | Bernabé et al., 2016 |

| R – CTTCACCAGTCTTAGCATCCTGAA | ||

Transcriptional Analysis of Biofilm Associated Virulence Factors

Real-time quantitative PCR was used to assess biofilm associated changes during biofilm formation with 1% sucrose. Biofilms were sonicated (Ultrasonic bath, Fisher scientific, United Kingdom) from the surface of the HA at 35 kHz for 10 min to harvest the cells. These were then washed by centrifugation prior to RNA extraction using a combined mechanical disruption (0.5 mm glass beads) and chemical TRIzolTM method (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom). After DNase treatment (Qiagen, Crawley, United Kingdom) and purification (RNeasy MinElute clean up kit, Qiagen, Crawley, United Kingdom), cDNA was synthesized using a High Capacity RNA to cDNA kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom), and quantitative PCR performed using a SYBR® GreenERTM assay (Life Technologies Ltd., Paisley, United Kingdom). The primers used for quantitative PCR were spaP (surface protein), gbpB (glucan binding protein B), gtfB (glucosyltransferases B), srtA (sortase A), luxS (S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase), ftf (fructosyltransferase) and 16S rRNA (Table 1). Each parameter was analyzed in duplicate using MxProP Quantitative PCR machine and MxProP 3000 software (Stratagene, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Gene expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene 16S rRNA according to 2-ΔΔCT method and percentage of gene expression is shown as log10 mean ± SD (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). A heat map was generated for the percentage expression of genes (log2) over the period of 24 to 120 h from the caries compared to caries-free group. Heat map was generated in R programming environment using the heatmap.2 function from the g-plots package.

Statistical Analysis

Data distribution, graph production and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5; La Jolla, CA, United States). After assessing whether data conformed to a normal distribution, One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and t-tests were used to investigate significant differences between independent groups of data that approximated to a Gaussian distribution. A Bonferroni correction was applied to the p value to account for multiple comparisons of the data. Any non-parametric data was analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U-test or the Kruskal–Wallis test with a Dunn’s post-test to assess differences between independent sample groups. Statistical significance was achieved if p < 0.05. A heatmap was created for the differential expression of genes (log2) over the period of 24, 72, and 120 h from the caries and non-caries S. mutans containing polymicrobial biofilms. Maps and clusters were generated in R with the use of heatmap.2 function from the g-plots package. All experiments were performed in triplicate on three independent occasions.

Results

Streptococcus mutans Mono-Species Biofilm Influenced by Carbohydrate Source

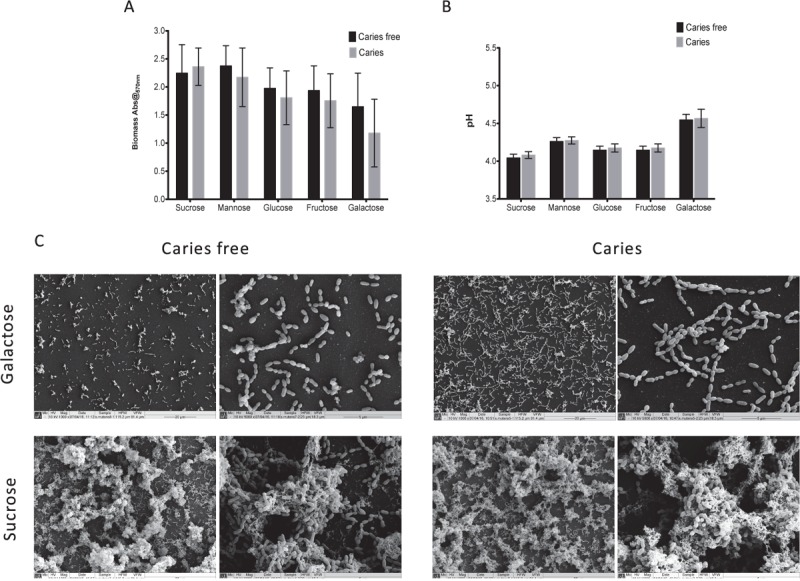

We first screened a large panel of S. mutans isolates derived from a clinical study under a standardized biofilms assay conditions (Yu et al., 2015). From these we randomly selected 10 isolates from caries patients and 10 from non-caries patients that were closest to the arithmetic mean (Supplementary Figure S1). The aim of this approach was to minimize any exaggerated biofilm formation effects associated with enhanced or reduced fitness within this heterogenous panel of clinical isolates. First, we aimed to assess and compare the ability of S. mutans to form mono-species biofilms in the presence of different dietary carbohydrates to determine whether we could observe strain dependent differences as mono-species biofilms. Initially, a range of concentrations were evaluated (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5% w/v) in terms of biomass and pH, with the resultant biofilm data demonstrating that the carbohydrate source, irrespective of concentration, showed a consistent trend (Supplementary Figure S2), i.e., sucrose consistently gave greater biomass and lower pH, whereas galactose displayed the contrasting polarized effects. We therefore focused on the concentration of 1% w/v with caries-free (n = 10) and caries (n = 10) isolates, a concentration which has been a consistently reported within analogous studies (Zeng et al., 2013; Liu S.S. et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2018). These data showed that although sucrose displayed the greatest biomass and lowest pH, followed by mannose, glucose, fructose and galactose, there were no significant differences between these caries groups in terms of biomass and pH (Figures 1A,B). These substrate specific differences are clearly evident when viewed under a SEM (Figure 1C), with isolates grown in galactose characterized by a single monolayer of sparse cells and lack of extracellular matrix, whereas isolates grown in sucrose were characterized by a three-dimensional architecture and excessive extracellular matrix and interconnected microcolonies. Overall, mono-species data confirmed that sucrose as a dietary carbohydrate enhanced S. mutans mono-species biofilm formation.

FIGURE 1.

Monospecies cariogenic biofilm biomass is influenced by carbohydrate source. Biomass was quantified spectrophotometrically by reading absorbance at 570 nm in a microtiter plate reader (FluoStar Omega, BMG Labtech). Four replicates were used for each isolate and was carried out on triplicate separate occasions, with the mean of each represented. Data represents mean with significance ∗p < 0.05. (A) Ten isolates with caries and caries free were standardized to 1 × 107 cells/mL in BHI with different carbohydrate and grown as biofilms in flat-bottomed 96 well microtiter plates for 24 h. Different concentrations of sucrose, mannose, fructose, glucose, galactose were added into BHI media (1.0% w/v). Biomass quantified by crystal violet staining. Biomass from caries group and caries free group were compared. (B) Supernatant of the mature biofilm were collected and the pH values of them were detected by pH meter. pH values from caries group and caries free group were compared. (C) Biofilms were also analyzed by SEM at both 1000× and 5000×. Samples were processed and viewed on a JEOL JSM-6400 scanning electron microscope and images assembled using Photoshop software. Strains from caries free group were grown in 1% galactose and 1% sucrose were compared with caries group separately.

Streptococcus mutans Exhibits Differential Activity Within a Polymicrobial Biofilm

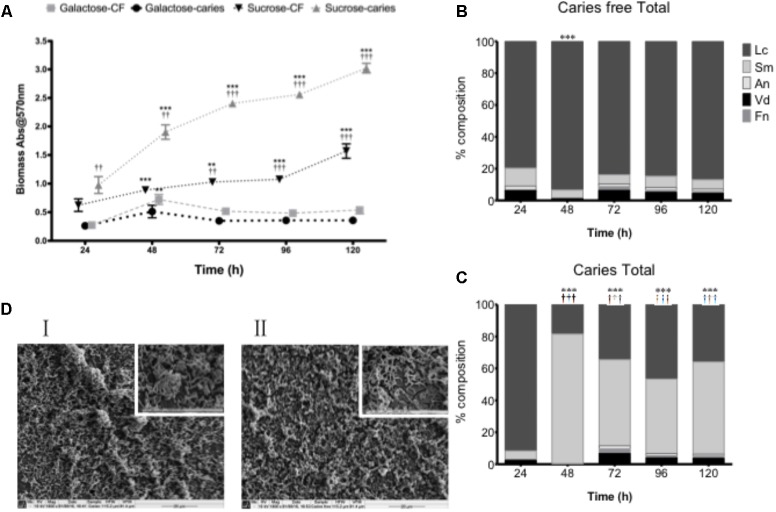

Although carbohydrates were shown to influence the biofilm architecture and environment as mono-species biofilms, structurally isolates from the caries and caries-free groups could not be phenotypically differentiated. We therefore hypothesized that S. mutans biofilm development may be influenced within a more physiologically relevant polymicrobial biofilm environmental state. To test this, we first assessed the total microbial biomass and composition of complex biofilms grown over a 120 h period, where significant growth was observed at each time point compared to 24 h in sucrose (p < 0.01) for the caries and non-caries containing biofilms (Figure 2A). Biofilms grown in galactose showed no discernable increase in biofilm biomass compared to the 24 h biofilm. Interestingly, significant differences were observed between the caries and caries free isolates grown in sucrose (p < 0.01) (Figure 2A). Further compositional analysis of the bacteria within the biofilm showed that the caries-free S. mutans containing biofilm was preferentially composed of L. casei (Figure 2B), which dominated throughout the period of growth and development. Whereas, the caries S. mutans containing biofilm was initially preferentially composed of L. casei, this was subsequently dominated by S. mutans from 48 to 120 h (Figure 2C). In galactose, L. casei dominated each biofilm, irrespective of the S. mutans isolate within each biofilm (Supplementary Figure S3). SEM analysis of the 120 h polymicrobial biomass from the caries and caries free containing S. mutans biofilms showed a dense and complicated intermixed population of morphologically different bacteria. Biofilms from the caries group were dominated by short chains of coccus-shaped bacteria compared to caries free group, which was instead preferentially dominated by rod-shaped bacteria (Figure 2D). Both biofilms displayed dense three-dimensional architecture on the hydroxyapatite substrate.

FIGURE 2.

Polymicrobial cariogenic biofilm biomass is influenced by carbohydrate source. (A) Polymicrobial caries biofilm model containing standardized L. casei, V. dispar, F. nucleatum, A. naeslundii and S. mutans isolates derived from either caries and caries-free patients grown at was grown in artificial saliva (AS) + either galactose or sucrose at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 5 days, with spent supernatants being replaced with fresh AS every 24 h. Biomass crystal violet staining was quantified spectrophotometrically at 570 nm. Significant increase in growth compared to the 24 h culture (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001). The total percentage composition of each bacterium grown in AS + 1% sucrose from (B) caries free and (C) caries derived S. mutans was quantified using species-specific qPCR (∗∗∗p < 0.001). Significant difference between the contribution of Lactobacillus at 24 h and other time-points indicated (∗∗∗p < 0.001). Significant difference between the contribution of S. mutans at 24 h and the time-points indicated (†††p < 0.001). (D) Polymicrobial biofilms were analyzed by SEM at ×1,000 and ×5,000. Biofilms from the caries group were dominated by short chains of coccus-shaped bacteria (I) compared to caries free group, which was dominated by rod-shaped bacteria (II).

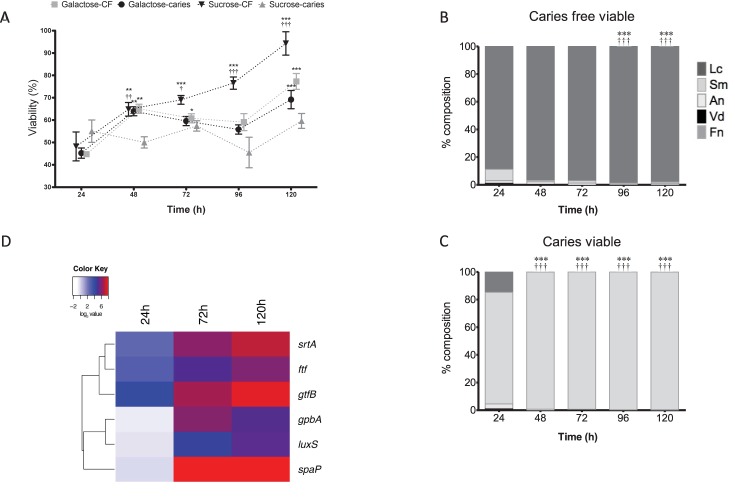

Next, we assessed the viability of these polymicrobial biofilms using a metabolic dye and PCR viability assay. A difference is observed in the viability of the caries group and caries free when grown under different sugar conditions. Notably, the S. mutans caries isolate containing biofilm showed minimal changes in metabolism when grown in sucrose, whereas the S. mutans caries-free isolate containing biofilm showed significantly increased metabolism in a time-dependent manner up to 120 h in comparison to 24 h biofilms (p < 0.001), and compared to the other groups tested (p < 0.001) (Figure 3A). No differences were observed in metabolic activity between the galactose group from caries or caries free, though these from the caries group were significantly increased at 120 h in comparison to the 24 h biofilms (p < 0.001) (Figure 3A). Furthermore, when these biofilms were investigated compositionally for viable cells, it was noted that S. mutans increasingly dominated the biofilms on a daily basis when the isolate was derived from a caries source (Figure 3B), whereas the caries-free S. mutans polymicrobial biofilm was increasingly dominated daily by viable L. casei (p < 0.001) (Figure 3C). These same analyzes were performed in galactose, however, there is no change between caries and caries free biofilms in terms of the dominating species (Supplementary Figure S3).

FIGURE 3.

Polymicrobial cariogenic biofilm viability is influenced by carbohydrate source. (A) Polymicrobial caries biofilm model containing standardized L. casei, V. dispar, F. nucleatum, A. naeslundii and S. mutans isolates derived from either caries and caries-free patients grown at was grown in artificial saliva (AS) + galactose or sucrose at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 5 days, with spent supernatants being replaced with fresh AS every 24 h. Metabolic activity (AlamarBlue) was quantified spectrophotometrically at 490 nm. Significant increase in growth compared to the 24 h culture (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001,††p < 0.01). The total viable percentage composition of each bacterium in AS + 1% sucrose from (B) caries free and (C) caries derived S. mutans was quantified using species-specific qPCR (∗∗∗p < 0.001). Significant difference between the contribution of Lactobacillus at 24 h and other time-points indicated (∗∗∗p < 0.001). Significant difference between the contribution of S. mutans at 24 h and the time-points indicated (†††p < 0.001). (D) A heatmap and clustering was created for the differential expression of genes (log2). These distinct patterns of gene expression show the related expression profiles of srtA, gtfB, and ftf, and overall upregulation of all genes at 120 h.

Given that the biofilms were compositionally distinct depending on the S. mutans isolate when grown in 1% sucrose, we then assessed the transcriptional expression of genes deemed important in the adhesion, colonization and associated pathogenicity as shown from the literature (Bernabé et al., 2016). It was shown that in the caries derived S. mutans polymicrobial biofilms that srtA, gtfB, and ftf were all upregulated after 24 h (18, 6, and 8%, respectively), 72 h (95, 70, and 32%, respectively) and 120 h (215, 132, and 62%, respectively) compared to non-caries derived biofilms. Whereas, initially at 24 h spaA, luxS, and gpbB were downregulated (0.91, 0.76, and 0.68%, respectively) in the caries derived S. mutans polymicrobial biofilms, before being upregulated at 72 h (418, 23, and 65%, respectively) and 120 h (364, 39, and 36%, respectively) compared to non-caries derived biofilms (Supplementary Figure S4). These patterns of differential expression are illustrated in the hierarchal clustered log2 transformed data, where these distinct patterns of gene expression show the related expression profiles of srtA, gtfB, and ftf, and overall upregulation of all genes at 120 h (Figure 3D).

Discussion

Caries continues to be a significant health problem, particularly amongst those in socially deprived areas, yet is entirely preventable (Pitts et al., 2017). We are all acutely aware that it is multifactorial dynamic disease and is mediated by biofilms. These biofilms are fuelled by sugars, resulting in the periodical phases of demineralization and remineralization of dental hard tissues. Microbiologically, S. mutans is recognized as the principal protagonist in caries progression, though its active role has been questioned through some functional transcriptomic techniques. It has been shown that prevalence and composition do not necessarily translate with Koch’s postulates. The data described herein demonstrates that caries microbiology is complex. Mixed consortia of acidogenic bacteria co-exist in biofilms with strain diversity playing an important role in driving the biofilm community structure, particularly under changing sugar conditions. This paper describes a caries polymicrobial biofilm model system that enables careful analysis of the composition and function.

We developed a novel dental caries biofilm model to form either S. mutans mono-species biofilms or polymicrobial biofilms including S. mutans and a range of bacteria grown in AS. This model is a closed batch culture system. Unlike rotary or continuous systems batch models do offer means of comparing multiple test compounds or conditions simultaneously; they only require small amounts of reagents and are convenient, reproducible, and economical to use (Coenye and Nelis, 2010). One of the most commonly used batch biofilm models is the Zurich biofilm model which uses six microbial species (Streptococcus oralis, S. sobrinus, A. naeslundii, V. dispar, F. nucleatum, and Candida albicans) (Guggenheim et al., 2004). A modification of this model is the three-species version (S. mutans, S. sanguinis, and A. naeslundii) to study the effect of xylitol in a young biofilm (Marttinen et al., 2012). Our model aims to refocus the Zurich biofilm model toward a cariogenic model with the addition of L. casei, which is a known antagonist to S. mutans (Ahmed et al., 2014). Other cariogenic models often have limited biodiversity and fail to encapsulate the impact of the biofilm in cariogenic outcomes (Chu et al., 2012; Mei et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2017). These models do not allow for the assessment of change in respect to the natural microbiome of the oral cavity. Within the modified model in this study, all the selected bacteria can be found in the process of dental caries (Simon-Soro et al., 2014). The main advantage of this model is its ease of use and requirements for relatively simple equipment, thus providing a robust model for use in the future.

Next, the response of mono-species biofilms to different carbohydrate sources was tested. Dietary carbohydrates were shown to have an impact on the dental caries biofilm model. The disaccharide sugar sucrose showed more cariogenic traits in the process of formation of S. mutans biofilm than the comparison monosaccharide sugars. Sucrose stimulated the S. mutans biofilm, forming the greatest biomass among the five carbohydrates through enhanced secretion of extracellular polysaccharide (EPS), as confirmed by SEM images. Koo et al. (2010) investigated the relationship between S. mutans and exopolysaccharides using the three-species model (S. mutans, S. oralis, and A. naeslundii). In this model ecological changes can be studied with respect to cariogenic biofilm formation. The addition of sucrose resulted in a shift in the proportion of the bacterial species, favoring S. mutans, thus producing an increase in biomass due to augmented exopolysaccharide production, a result that has been replicated within this study (Koo et al., 2010). A direct correlation between sugar consumption and higher caries experience by DMFT index has recently been confirmed (Bernabé et al., 2016). Utilization of sucrose by S. mutans is the key cariogenic trait leading to the development of dental caries. The present study confirmed that as a sugar source sucrose was more cariogenic than galactose. S. mutans metabolizes sucrose into glucan, which is a component of the extracellular matrix. S. mutans is endowed with efficient metabolic mechanisms to better utilize free sugars over fermentable substrates, such as starch, thus promoting the formation of cariogenic biofilms.

Surprisingly, S. mutans strains within a polymicrobial biofilm environmental state do not conform to a specific pattern of growth. Significant differences were observed, and were not only dependent on the sugars, but also on specific isolates. Liu S.S. et al. (2017) revealed S. mutans isolates varied in their ability to compete and become dominant in the biofilm after the addition of sucrose (Liu Y. et al., 2017). Interactions between microorganisms colonizing the oral cavity are consecutive factors affecting the development of biofilm, with interactions occurring between microorganisms resulting in both the acceleration and inhibition of this process (Wen et al., 2010; Redanz et al., 2011). The compositional analysis described herein showed that S. mutans was the dominant species within the biofilm containing the caries isolate, while more L. casei were present in the biofilm containing the caries-free isolate. This could merely be coincidence, so we do not suggest that these outcomes from this model represent a predictor of carious potential. Instead, we present a model that enables us to investigate compositional and functional changes within complex biofilms, while also assessing functional changes driven by transcriptional changes. S. mutans may interact with Lactobacillus to accelerate or inhibit the process of biofilm formation depending on the isolate strains. L. salivarius strains with inhibitory activities on the growth and expression of S. mutans virulence genes have been shown to reduce its biofilm formation in many studies similar to data shown within (Wu et al., 2015; Krzysciak et al., 2017). Lactobacillus spp. inhibit the proliferation of the pathogen, and thus retard biofilm formation and development through LuxS and GtfB (Samot et al., 2011; Söderling et al., 2011; Ahmed et al., 2014). Conversely, it has been shown that biofilm formation by S. mutans significantly decreased when grown with S. sanguinis, but slightly increased when co-cultivated with L. casei, thus further highlighting the diversity and variability in isolates (Takahashi and Nyvad, 2011).

Real-time PCR was used to analyze the expression of genes that have critical roles in bacterial adherence and biofilm accumulation by S. mutans (Banas, 2004). Results show that the expression of these genes increased in polymicrobial biofilms containing caries isolates. It was identified that not only genes that are associated with sucrose metabolism (gtfB, ftf) were increased within the biofilm, but genes associated in non-sucrose metabolism (srtA, spaP, gbpB) were also enhanced. Elucidating that these are also involved in the utilization of sucrose and enhanced the cariogenic properties of the biofilm. Klein et al. (2012) showed that S. mutans adapts to a multi-species environment by changing the expression of genes associated with glucan synthesis, remodeling, and glucan-binding (Klein et al., 2012). In this way, S. mutans outcompetes other bacteria by optimizing its metabolism to a sucrose environment, thus increasing its competitiveness and thereby virulence. Collectively, this illustrates that cariogenic biofilms containing S. mutans are complex, and dependent upon the specific strains present thus driving different cariogenic phenotypes.

Biofilms are a multi-species complex attached on the tooth surface, with a myriad of consecutive factors contributing to biofilm development, which can result in both the acceleration and inhibition of this process (Simon-Soro et al., 2014). The study presented herein aims to provide a dynamic approach to studying the changes in biofilm under dietary pressure. This provides evidence that S. mutans in mixed-species communities interacts with other microorganisms depending upon the composition and specific phenotypes, thus driving dominant ecotypes. This is particularly important given the heterogeneity that exists within this species (Palmer et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2015). The virulence of S. mutans depends not only on the environmental conditions of the oral cavity, but also on the composition of the microbiome, and indeed the mycobiome (Ghannoum et al., 2010; Peters et al., 2017). Therefore, the model developed and presented offers useful and advantageous methodologies to test different experimental hypotheses related to caries research.

Author Contributions

YZ, EM, and TS participated in the study design, carried out the experimental studies on biofilms, and performed statistical analysis; they were responsible for the manuscript. DL participated in study design, assisted with statistical support, and helped draft the manuscript. RR carried out the molecular studies on biofilms and helped draft the manuscript. JB and HL contributed to study design and supervised manuscript writing. GR conceived the study, participated in study design, data analysis, and was responsible for writing and submission of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Margaret Mullin (University of Glasgow) for her assistance in scanning electron microscopy techniques.

Footnotes

Funding. YZ as supported by the China Scholarship Council (File No. 201406385066). EM was funded through an Industrial BBSRC CASE studentship (BB/J500318/1).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01498/full#supplementary-material

Streptococcus mutans mono-species biofilm formation from clinical isolates is phenotypically variable. Standardized S. mutans isolates (1 × 107 cells/mL) in BHI media with 0.25% sucrose were grown in flat-bottomed 96 well microtiter plates for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Mature biofilms were carefully washed with PBS, allowed to air dry and biomass quantified by staining with 0.05% w/v crystal violet solution. The biofilms were washed and de-stained with 100% ethanol. Biomass was quantified spectrophotometrically by reading absorbance at 570 nm in a microtiter plate reader (FluoStar Omega, BMG Labtech). Four replicates were used for each isolate and was carried out on triplicate separate occasions, with the mean of each represented.

Standardized S. mutans (ten isolates from caries and caries free patients) at 1 × 107 cells/mL in BHI media containing different concentrations of sucrose, mannose, fructose, glucose, galactose (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0% w/v) for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Biomass crystal violet staining was quantified spectrophotometrically at 570 nm and supernatants collected and pH values quantified. Four replicates were used for each isolate (n = 3), with the mean of each represented. Data represents the mean.

Polymicrobial caries biofilm model containing standardized L. casei, V. dispar, F. nucleatum, A. naeslundii, and S. mutans isolates derived from either caries and caries-free patients grown at was grown in artificial saliva (AS) + galactose at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 5 days. Biofilms were assessed for total and viable composition of each bacterium using viability qPCR.

Polymicrobial caries biofilm model containing standardized L. casei, V. dispar, F. nucleatum, A. naeslundii, and S. mutans isolates derived from either caries and caries-free patients grown at was grown in artificial saliva (AS) + galactose at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 5 days. Total bacterial RNA was extracted and transcriptional analysis performed on srtA, spaA, luxS, ftf, spaP and gpbB. Gene expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene 16S rRNA according to 2-ΔΔCT method and a heat map generated using the heatmap.2 function from the g-plots package.

References

- Ahmed A., Dachang W., Lei Z., Jianjun L., Juanjuan Q., Yi X. (2014). Effect of Lactobacillus species on Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 27 1523–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banas J. A. (2004). Virulence properties of Streptococcus mutans. Front. Biosci. 9 1267–1277. 10.2741/1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernabé E., Vehkalahti M. M., Sheiham A., Lundqvist A., Suominen A. L. (2016). The shape of the dose-response relationship between sugars and caries in adults. J. Dent. Res. 95 167–172. 10.1177/0022034515616572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen W. H., Koo H. (2011). Biology of Streptococcus mutans-derived glucosyltransferases: role in extracellular matrix formation of cariogenic biofilms. Caries Res. 45 69–86. 10.1159/000324598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J. N., Jung J. E., Lee M. H., Choi H. M., Jeon J. G. (2018). Sucrose challenges to Streptococcus mutans biofilms and the curve fitting for the biofilm changes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94:fiy091. 10.1093/femsec/fiy091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C. H., Mei L., Seneviratne C. J., Lo E. C. (2012). Effects of silver diamine fluoride on dentine carious lesions induced by Streptococcus mutans and Actinomyces naeslundii biofilms. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 22 2–10. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01149.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenye T., Nelis H. J. (2010). In vitro and in vivo model systems to study microbial biofilm formation. J. Microbiol. Methods 83 89–105. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A. R., Shah N. P., Powell I. B. (2006). Discrimination of dairy industry isolates of the Lactobacillus casei group. J. Dairy Sci. 89 3345–3351. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72371-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlandsen S. L., Kristich C. J., Dunny G. M., Wells C. L. (2004). High-resolution visualization of the microbial glycocalyx with low-voltage scanning electron microscopy: dependence on cationic dyes. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 52 1427–1435. 10.1369/jhc.4A6428.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum M. A., Jurevic R. J., Mukherjee P. K., Cui F., Sikaroodi M., Naqvi A., et al. (2010). Characterization of the oral fungal microbiome (mycobiome) in healthy individuals. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000713. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggenheim B., Guggenheim M., Gmur R., Giertsen E., Thurnheer T. (2004). Application of the Zurich biofilm model to problems of cariology. Caries Res. 38 212–222. 10.1159/000077757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M. I., Xiao J., Lu B., Delahunty C. M., Yates J. R. 3rd. and Koo H. (2012). Streptococcus mutans protein synthesis during mixed-species biofilm development by high-throughput quantitative proteomics. PLoS One 7:e45795. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H., Xiao J., Klein M. I., Jeon J. G. (2010). Exopolysaccharides produced by Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferases modulate the establishment of microcolonies within multispecies biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 192 3024–3032. 10.1128/JB.01649-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzysciak W., Koscielniak D., Papiez M., Vyhouskaya P., Zagorska-Swiezy K., Kolodziej I., et al. (2017). Effect of a Lactobacillus Salivarius probiotic on a double-species Streptococcus mutans and candida albicans caries biofilm. Nutrients 9:E1242. 10.3390/nu9111242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembo F. L., Longo P. L., Ota-Tsuzuki C., Rodrigues C. R., Mayer M. P. (2007). Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of Streptococcus mutans from different oral cavity sites of caries-free and caries-active children. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 22 313–319. 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00361.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque C. M., Voronejskaia E., Huang Y. C., Mair R. W., Ellen R. P., Cvitkovitch D. G. (2005). Involvement of sortase anchoring of cell wall proteins in biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 73 3773–3777. 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3773-3777.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. S., Zhu W. H., Zhi Q. H., Liu J., Wang Y., Lin H. C. (2017). Analysis of sucrose-induced small RNAs in Streptococcus mutans in the presence of different sucrose concentrations. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101 5739–5748. 10.1007/s00253-017-8346-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Palmer S. R., Chang H., Combs A. N., Burne R. A., Koo H. (2017). Differential oxidative stress tolerance of Streptococcus mutans isolates affects competition in an ecological mixed-species biofilm model. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 10 12–22. 10.1111/1758-2229.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesche W. J. (1986). Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 50 353–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttinen A. M., Ruas-Madiedo P., Hidalgo-Cantabrana C., Saari M. A., Ihalin R. A., Soderling E. M. (2012). Effects of xylitol on xylitol-sensitive versus xylitol-resistant Streptococcus mutans strains in a three-species in vitro biofilm. Curr. Microbiol. 65 237–243. 10.1007/s00284-012-0151-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei M. L., Li Q. L., Chu C. H., Lo E. C., Samaranayake L. P. (2013). Antibacterial effects of silver diamine fluoride on multi-species cariogenic biofilm on caries. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 12:4. 10.1186/1476-0711-12-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millhouse E., Jose A., Sherry L., Lappin D. F., Patel N., Middleton A. M., et al. (2014). Development of an in vitro periodontal biofilm model for assessing antimicrobial and host modulatory effects of bioactive molecules. BMC Oral Health 14:80. 10.1186/1472-6831-14-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napimoga M. H., Hofling J. F., Klein M. I., Kamiya R. U., Goncalves R. B. (2005). Tansmission, diversity and virulence factors of Streptococcus mutans genotypes. J. Oral Sci. 47 59–64. 10.2334/josnusd.47.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer S. R., Miller J. H., Abranches J., Zeng L., Lefebure T., Richards V. P., et al. (2013). Phenotypic heterogeneity of genomically-diverse isolates of Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 8:e61358. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy S., Chalmers N. I., Du-Thumm L., Kolenbrander P. E. (2009). Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC 10953 requires Actinomyces naeslundii ATCC 43146 for growth on saliva in a three-species community that includes Streptococcus oralis 34. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 3250–3257. 10.1128/AEM.02901-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters B. A., Wu J., Hayes R. B., Ahn J. (2017). The oral fungal mycobiome: characteristics and relation to periodontitis in a pilot study. BMC Microbiol. 17:157. 10.1186/s12866-017-1064-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts N. B., Zero D. T., Marsh P. D., Ekstrand K., Weintraub J. A., Ramos-Gomez F., et al. (2017). Dental caries. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 3:17030. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redanz S., Standar K., Podbielski A., Kreikemeyer B. (2011). A five-species transcriptome array for oral mixed-biofilm studies. PLoS One 6:e27827. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samot J., Lebreton J., Badet C. (2011). Adherence capacities of oral lactobacilli for potential probiotic purposes. Anaerobe 17 69–72. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senadheera D., Cvitkovitch D. G. (2008). Quorum sensing and biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 631 178–188. 10.1007/978-0-387-78885-2_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry L., Lappin G., O’donnell L. E., Millhouse E., Millington O. R., Bradshaw D. J., et al. (2016). Viable compositional analysis of an eleven species oral polymicrobial biofilm. Front. Microbiol. 7:912. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Soro A., Guillen-Navarro M., Mira A. (2014). Metatranscriptomics reveals overall active bacterial composition in caries lesions. J. Oral Microbiol. 6:25443. 10.3402/jom.v6.25443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderling E. M., Marttinen A. M., Haukioja A. L. (2011). Probiotic lactobacilli interfere with Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation in vitro. Curr. Microbiol. 62 618–622. 10.1007/s00284-010-9752-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Nyvad B. (2008). Caries ecology revisited: microbial dynamics and the caries process. Caries Res. 42 409–418. 10.1159/000159604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Nyvad B. (2011). The role of bacteria in the caries process: ecological perspectives. J. Dent. Res. 90 294–303. 10.1177/0022034510379602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z. T., Yates D., Ahn S. J., Burne R. A. (2010). Biofilm formation and virulence expression by Streptococcus mutans are altered when grown in dual-species model. BMC Microbiol. 10:111. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. C., Lin C. T., Wu C. Y., Peng W. S., Lee M. J., Tsai Y. C. (2015). Inhibitory effect of Lactobacillus salivarius on Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 30 16–26. 10.1111/omi.12063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. X., Tao Y., Qiu R. M., Zhou Y., Zhi Q. H., Lin H. C. (2015). Genetic polymorphisms of the sortase a gene and social-behavioural factors associated with caries in children: a case-control study. BMC Oral Health 15:54. 10.1186/s12903-015-0039-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu O. Y., Zhao I. S., Mei M. L., Lo E. C., Chu C. H. (2017). A review of the common models used in mechanistic studies on demineralization-remineralization for cariology research. Dent. J. 5:E20. 10.3390/dj5020020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaura E., Brandt B. W., Prodan A., Teixeira De Mattos M. J., Imangaliyev S., Kool J., et al. (2017). On the ecosystemic network of saliva in healthy young adults. ISME J. 11 1218–1231. 10.1038/ismej.2016.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L., Xue P., Stanhope M. J., Burne R. A. (2013). A galactose-specific sugar: phosphotransferase permease is prevalent in the non-core genome of Streptococcus mutans. Mol. Oral. Microbiol. 28 292–301. 10.1111/omi.12025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Streptococcus mutans mono-species biofilm formation from clinical isolates is phenotypically variable. Standardized S. mutans isolates (1 × 107 cells/mL) in BHI media with 0.25% sucrose were grown in flat-bottomed 96 well microtiter plates for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Mature biofilms were carefully washed with PBS, allowed to air dry and biomass quantified by staining with 0.05% w/v crystal violet solution. The biofilms were washed and de-stained with 100% ethanol. Biomass was quantified spectrophotometrically by reading absorbance at 570 nm in a microtiter plate reader (FluoStar Omega, BMG Labtech). Four replicates were used for each isolate and was carried out on triplicate separate occasions, with the mean of each represented.

Standardized S. mutans (ten isolates from caries and caries free patients) at 1 × 107 cells/mL in BHI media containing different concentrations of sucrose, mannose, fructose, glucose, galactose (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0% w/v) for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Biomass crystal violet staining was quantified spectrophotometrically at 570 nm and supernatants collected and pH values quantified. Four replicates were used for each isolate (n = 3), with the mean of each represented. Data represents the mean.

Polymicrobial caries biofilm model containing standardized L. casei, V. dispar, F. nucleatum, A. naeslundii, and S. mutans isolates derived from either caries and caries-free patients grown at was grown in artificial saliva (AS) + galactose at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 5 days. Biofilms were assessed for total and viable composition of each bacterium using viability qPCR.

Polymicrobial caries biofilm model containing standardized L. casei, V. dispar, F. nucleatum, A. naeslundii, and S. mutans isolates derived from either caries and caries-free patients grown at was grown in artificial saliva (AS) + galactose at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 5 days. Total bacterial RNA was extracted and transcriptional analysis performed on srtA, spaA, luxS, ftf, spaP and gpbB. Gene expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene 16S rRNA according to 2-ΔΔCT method and a heat map generated using the heatmap.2 function from the g-plots package.