Abstract

Background

Despite the recent acceptance of thrombectomy as the standard of care in patients with acute anterior circulation stroke, the benefits of thrombectomy remain uncertain for patients with acute basilar artery occlusion (BAO). This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of thrombectomy and to identify predictors of outcomes in a large cohort of patients with acute BAO.

Methods and Results

This study included 212 consecutive patients with acute BAO who underwent either stent‐retriever or contact aspiration thrombectomy as the first‐line approach between January 2011 and August 2017 at 3 stroke centers. Clinical and radiologic data were prospectively collected and stored in a database at each center. Multivariable ordinal logistic regression was performed to assess the association between each characteristic and 90‐day modified Rankin scale scores. Reperfusion was successful in 91.5% (194/212) of patients; 44.8% (95/212) of patients achieved 90‐day modified Rankin scale 0 to 2. The symptomatic hemorrhage rate was 1.9% (4/212) and mortality was 16% (34/212). In a multivariable ordinal regression, younger age, lower National Institute of Health stroke scale on admission, and absence of diabetes mellitus and parenchymal hematoma were significantly associated with a favorable shift in the overall distribution of 90‐day modified Rankin scale scores. Treatment outcomes were similar between patients who received stent‐retriever thrombectomy and contact aspiration thrombectomy as the first‐line technique.

Conclusions

Endovascular thrombectomy was effective and safe for treating patients with acute BAO. Age, the baseline National Institute of Health stroke scale, diabetes mellitus, and parenchymal hematoma were associated with better outcomes. This study showed no superiority of the stent‐retriever over the aspiration thrombectomy for treating acute BAO.

Keywords: basilar artery occlusion, ischemic, posterior circulation, stroke, thrombectomy

Subject Categories: Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke, Ischemic Stroke, Revascularization

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Thrombectomy could provide a high rate of successful reperfusion (91.5%) and a high rate of favorable outcomes (44.8%) in patients with acute basilar artery occlusion in this multicenter retrospective observational study.

Thrombectomy was safe for treating acute basilar artery occlusion, with low rates of mortality (13%), symptomatic hemorrhage (1.9%), and procedure‐related complications (4.2%).

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Thrombectomy might be considered the standard of care for eligible patients with acute basilar artery occlusion, despite the lack of a published randomized controlled trial to date.

Introduction

Acute stroke caused by basilar artery occlusion (BAO) has devastating effects on patients. The outcome and mortality associated with BAO are worse than those associated with anterior circulation stroke.1, 2, 3 Despite the recent acceptance of thrombectomy as the standard of care in patients with acute anterior circulation stroke,4 the effectiveness and safety of modern thrombectomy remains uncertain for patients with acute BAO. Although multiple case studies have described endovascular therapy for acute BAO, previous studies are limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneous patient populations, and the use of older generation devices and techniques.3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Moreover, several important issues remain to be elucidated, such as identifying predictors of functional outcome after modern thrombectomy or the selection of a first‐line thrombectomy technique for patients with acute BAO. This multicenter, retrospective, observational study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of modern endovascular thrombectomy and to identify predictors of a better functional outcome after thrombectomy in a large cohort of patients with acute BAO‐related stroke. In addition, we compared treatment outcomes between 2 first‐line thrombectomy techniques: the stent‐retriever versus the contact aspiration technique.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. This retrospective, multicenter, observational study, termed ENTHUSE (Endovascular thrombectomy for acute basilar artery occlusion), was conducted at 3 high‐volume stroke centers (≥100 thrombectomies performed annually) in South Korea. We included all consecutive patients with acute BAO who underwent a modern thrombectomy, between January 2011 and August 2017. Of these, patients with a premorbid modified Rankin scale (mRS) ≥2 were excluded from this study. Clinical and radiologic data were prospectively collected and stored in a database at each center. The following data were retrieved from the databases for retrospective review: age, sex, stroke risk factors, baseline National Institute of Health stroke scale (NIHSS) score, the use of intravenous thrombolysis, estimated time of stroke onset,10 time from onset to procedure, procedure duration, time from onset to reperfusion, first‐line thrombectomy technique (stent‐retriever or contact aspiration), underlying severe intracranial stenosis, steno‐occlusive lesion in the origin of vertebral artery, stroke subtype, procedure‐related complications, reperfusion status, and 90‐day mRS. The retrospective data review study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each center. Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of this study. The data that support the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Before the thrombectomy, all patients underwent baseline imaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) according to the acute stroke imaging protocol at each center. At all centers, patients were considered eligible for thrombectomy if the thrombectomy could be started within 12 hours of the estimated time of stroke onset and had an angiographically confirmed occlusion in the basilar artery. Patients were excluded from thrombectomy when pretreatment imaging showed extensive ischemic changes in the brain stem or the stroke was considered mild, based on an admission NIHSS score of 3 or less. There was no upper limitation on either the admission NIHSS score or age for selecting patients at all centers. According to guidelines, before thrombectomy, intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator was administered to eligible patients who could be treated within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.

Endovascular Thrombectomy

All patients were treated with thrombectomy, performed with either the stent‐retriever or the contact aspiration technique. The choice of technique was left to the discretion of the treating neurointerventionist. The details of these thrombectomy techniques were described previously.11, 12, 13 When the selected first‐line thrombectomy technique failed to achieve successful reperfusion, the neurointerventionist switched to the other technique. When an underlying, severe (≥70%) atherosclerotic stenosis was found in the basilar artery during the thrombectomy, a subsequent rescue procedure was performed. This rescue procedure involved either an intra‐arterial infusion of an antiplatelet agent (tirofiban) or an intracranial angioplasty, with or without stenting. No patient underwent general anesthesia in this study.

Outcome Measures

The time to procedure was defined as the interval between the estimated time of stroke onset and the time of femoral artery puncture. The estimated time of stroke onset was defined as the time of onset of acute symptoms that led to clinical diagnosis of BAO or, when the onset time was not known, the last time the patient was observed in a normal state before the onset of these symptoms.10 Procedure duration was defined as the interval between the time of femoral artery puncture and the time of final angiogram. Intracerebral hemorrhages were assessed with post‐treatment computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans and classified as a subarachnoid hemorrhage, hemorrhagic infarction, or parenchymal hematoma, based on the ECASS (European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study) II criteria.14 A symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was also defined according to the ECASS II classification. Procedure‐related complications were recorded, including arterial dissection, vessel rupture, or distal embolization to a new territory. Reperfusion status was assessed on the final angiogram, according to the m‐TICI (modified Treatment in Cerebral Infarction) scale.15 Successful reperfusion was defined as an m‐TICI grade of 2b or 3. Image analysis was performed by neuroradiologists at each center. Clinical outcome was assessed with the mRS score, by stroke neurologists at each center, during an outpatient visit, 90 days after treatment. When patients were unable to attend the outpatient clinic, outcomes were assessed in telephone interviews.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were expressed as the count (n) and percentage (%). First, a relationship was determined between each clinical and procedural characteristic and the dichotomized 90‐day outcome (mRS 0–2 versus 3–6). The χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical and binary variables. The independent sample t test was used to compare continuous variables. Second, we performed univariable and multivariable ordinal logistic regressions to estimate the common odds ratio (cOR) of each potential predictor for a shift in the direction of better outcomes on the 90‐day mRS (shift analysis). The variables with P<0.05 in the univariate ordinal regression analysis were selected for the multivariable ordinal logistic regression model. Third, we evaluated differences in treatment outcomes (successful reperfusion, intracranial hemorrhages, 90‐day mRS 0–2, and mortality) between patients treated with a stent‐retriever thrombectomy and those treated with contact aspiration thrombectomy as the first‐line strategy. Finally, we compared treatment outcomes between patients who received intraarterial tirofiban infusion and those who underwent intracranial angioplasty with or without stenting for treatment of underlying severe stenosis in the basilar artery. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). A P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

This study included 212 patients (56.6% male; median age 71; age range, 36–93 years) who received a thrombectomy because of acute BAO. The baseline characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. In the entire cohort, 62.7% (133/212) of patients had hypertension, 44.8% (95/212) had atrial fibrillation, 28.8% (61/212) had diabetes mellitus, 25.0% (53/212) had a smoking history, 25.0% (53/212) had hyperlipidemia, 19.8% (42/212) had a history of prior ischemic stroke, and 10.4% (22/212) had a history of previous coronary artery disease. Diffusion‐weighted imaging was performed before thrombectomy in 92% (195/212) of patients. The median NIHSS score was 17 on admission. Intravenous thrombolysis was performed before thrombectomy in 30.7% (65/212) of patients. Underlying severe intracranial stenosis was found at the occlusion site in 55 patients (25.9%). Twenty‐five patients (11.8%) had a steno‐occlusive lesion located at the origin of the vertebral artery.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population: Patients With Acute BAO

| Characteristics | All Patients (n=212) | 90‐Day mRS 0 to 2 (n=95) | 90‐Day mRS 3 to 6 (n=117) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 71 (64–78) | 67 (61–74) | 74 (67–80) | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 120 (56.6%) | 53 (55.8%) | 67 (57.3%) | 0.829 |

| Risk factor | ||||

| Hypertension | 133 (62.7%) | 49 (51.6%) | 84 (71.8%) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 61 (28.8%) | 18 (18.9%) | 43 (36.8%) | 0.004 |

| Smoking | 53 (25.0%) | 24 (25.3%) | 29 (24.8%) | 0.936 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 53 (25.0%) | 32 (33.7%) | 21 (17.9%) | 0.009 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 95 (44.8%) | 40 (42.1%) | 55 (47.0%) | 0.475 |

| Previous stroke/TIA | 42 (19.8%) | 14 (14.7%) | 28 (23.9%) | 0.095 |

| Coronary artery disease | 22 (10.4%) | 6 (6.3%) | 16 (13.7%) | 0.081 |

| Intravenous thrombolysis | 65 (30.7%) | 32 (33.7%) | 33 (28.2%) | 0.390 |

| Occlusion sites | ||||

| Proximal | 52 (24.5%) | 25 (26.3%) | 27 (23.1%) | 0.586 |

| Middle | 48 (22.6%) | 18 (18.9%) | 30 (25.6%) | 0.247 |

| Distal | 112 (52.8%) | 52 (54.7%) | 60 (51.3%) | 0.616 |

| Time from onset to groin puncture, min, median (IQR) | 242 (167.5–357) | 223 (150–340) | 270 (182.5–371) | 0.435 |

| Procedure duration, min, median (IQR) | 40 (25–69.75) | 36 (22–58) | 45 (28.5–81.5) | 0.037 |

| Time from onset to reperfusion, min, median (IQR) | 295 (224–423.75) | 280 (195–375) | 319 (239–446.5) | 0.206 |

| Baseline NIHSS, median (IQR) | 17 (10–23.75) | 12 (7–20) | 20 (14.5–25.5) | <0.001 |

| First‐line thrombectomy technique | ||||

| Stent‐retriever | 145 (68.4%) | 68 (71.6%) | 77 (65.8%) | 0.369 |

| Contact aspiration | 67 (31.6%) | 27 (28.4%) | 40 (34.2%) | |

| Use of alternative thrombectomy technique | 47 (22.2%) | 17 (17.9%) | 30 (25.6%) | 0.177 |

| Underlying severe basilar artery stenosis | 55 (25.9%) | 27 (28.4%) | 28 (23.9%) | 0.458 |

| VA ostial steno‐occlusive lesion | 25 (11.8%) | 13 (13.7%) | 12 (10.3%) | 0.442 |

| Stroke cause | ||||

| Cardioembolism | 101 (47.6%) | 42 (44.2%) | 59 (50.4%) | 0.367 |

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 82 (38.7%) | 38 (40%) | 44 (37.6%) | 0.722 |

| Undetermined | 25 (11.8%) | 15 (15.8%) | 10 (8.5%) | 0.104 |

| Others | 4 (1.9%) | 0 | 4 (3.4%) | 0.130 |

Values represent the number of patients (%), unless otherwise indicated. BAO indicates basilar artery occlusion; IQR, interquartile range; mRS, modified Rankin scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health stroke scale; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VA, vertebral artery.

Overall, the thrombectomy resulted in 91.5% (194/212) successful reperfusions (m‐TICI 2b or 3), 63.2% (134/212) complete reperfusions (m‐TICI 3), and 44.8% (95/212) 90‐day mRS 0 to 2. Other treatment outcomes included 18.4% (39/212) hemorrhagic infarctions, 4.2% (9/212) parenchymal hemorrhages, and 3.3% (7/212) subarachnoid hemorrhages. Symptomatic hemorrhage occurred in 4 patients (1.9%). The mortality rate was 16% (34/212). Procedure‐related complications occurred in 9 patients: 6 experienced distal embolization, 2 experienced vessel rupture, and 1 experienced arterial dissection.

Treatment Outcomes and Results of Shift Analysis

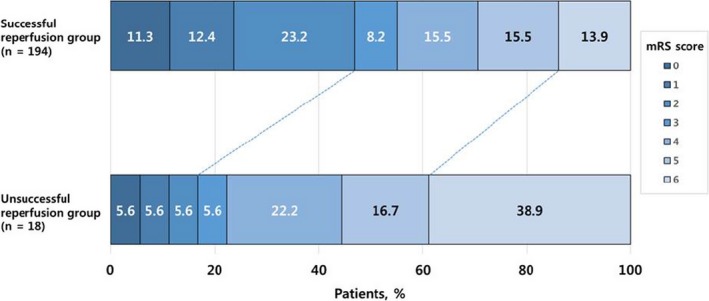

Associations between the distribution of the 90‐day mRS scores and treatment outcomes are presented in Table 2. There was a shift toward better outcomes in favor of the successful reperfusion (cOR, 3.597; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.496–8.645; P=0.004) (Figure) and complete reperfusion (cOR, 2.408; 95% CI, 1.458–3.978; P=0.001). The occurrence of hemorrhagic infarction (cOR, 0.468; 95% CI, 0.252–0.868; P=0.016) and parenchymal hematoma (cOR, 0.097; 95% CI, 0.025–0.377; P=0.001) was significantly associated with a shift of mRS scores toward poor outcomes.

Table 2.

Associations Between 90‐Day Modified Rankin Scale Scores and Treatment Outcomes After Thrombectomy in 212 Patients With Acute BAO

| Outcomes | All Patientsa | Unadjusted cOR (95% CI)b | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful reperfusion | 194 (91.5%) | 3.597 (1.496–8.645) | 0.004 |

| Complete reperfusion | 134 (63.2%) | 2.408 (1.458–3.978) | 0.001 |

| Hemorrhagic infarction | 39 (18.4%) | 0.468 (0.252–0.868) | 0.016 |

| Parenchymal hematoma | 9 (4.2%) | 0.097 (0.025–0.377) | 0.001 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 7 (3.3%) | 0.434 (0.114–1.652) | 0.221 |

BAO indicates basilar artery occlusion; CI, confidence interval; cOR, common odds ratio.

Values represent the number of patients (%).

Values were obtained by univariable ordinal regression analysis.

Figure 1.

Distribution of modified Rankin scale scores at 90 days, according to reperfusion status after thrombectomy, in patients with acute basilar artery occlusion. There was a significant difference between the successful reperfusion group and the unsuccessful reperfusion group in the overall distribution of scores in univariable ordinal regression (unadjusted common odds ratio, 3.597; 95% confidence interval, 1.496–8.645; P=0.004). mRS, modified Rankin scale.

Table 3 shows the results of multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis for predicting better outcomes. The variables included in the multivariable model were age, baseline NIHSS, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, procedure duration, reperfusion status (m‐TICI 2b or 3), and occurrence of hemorrhagic infarction and parenchymal hematoma. Of the variables included, statistically significant predictors of better outcomes were younger age (adjusted cOR, 0.951; 95% CI, 0.929–0.974; P<0.001), lower baseline NIHSS (adjusted cOR, 0.904; 95% CI, 0.875–0.935; P<0.001), absence of diabetes mellitus (adjusted cOR, 0.428; 95% CI, 0.244–0.751; P=0.003), and absence of parenchymal hematoma (adjusted cOR, 0.074; 95% CI, 0.017–0.312; P<0.001).

Table 3.

Multivariable Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis Results Show Independent Predictors of Better Outcomes At 90 Days

| Variables | Unadjusted cOR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted cOR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, per 1‐y increase | 0.958 (0.936–0.979) | <0.001 | 0.951 (0.929–0.974) | <0.001 |

| Baseline NIHSS, per 1‐point increase | 0.896 (0.868–0.925) | <0.001 | 0.904 (0.875–0.935) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.529 (0.323–0.868) | 0.012 | 0.709 (0.420–1.198) | 0.199 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.524 (0.309–0.889) | 0.017 | 0.428 (0.244–0.751) | 0.003 |

| Procedure duration, per 1‐min increase | 0.993 (0.988–0.998) | 0.008 | 0.998 (0.992–1.004) | 0.597 |

| Successful reperfusion | 3.597 (1.496–8.645) | 0.004 | 2.517 (0.898–7.050) | 0.079 |

| Hemorrhagic infarction | 0.468 (0.252–0.868) | 0.016 | 0.687 (0.360–1.313) | 0.256 |

| Parenchymal hematoma | 0.097 (0.025–0.377) | 0.001 | 0.074 (0.017–0.312) | <0.001 |

CI indicates confidence interval; cOR, common odds ratio; NIHSS, National Institute of Health stroke scale.

Stent‐Retriever Versus Contact Aspiration as the First‐Line Thrombectomy Technique

The first‐line technique was stent‐retriever thrombectomy in 68.4% (145/212) of patients and contact aspiration thrombectomy in 31.6% (67/212) of patients. Patients treated with contact aspiration had a higher median admission NIHSS than patients treated with a stent‐retriever (20 versus 16, P=0.002). The procedure time tended to be shorter with the stent‐retriever (38 minutes versus 44 minutes, P=0.067) than with contact aspiration. There was no difference between groups in age, risk factors, use of intravenous thrombolysis, stroke cause, incidence of underlying severe stenosis, or the incidence of steno‐occlusive lesions at the vertebral artery origin.

Treatment outcomes (Table 4) were similar between the 2 approaches. There were no differences in the rates of conversion to secondary thrombectomy, successful reperfusion, complete reperfusion, hemorrhagic infarction, parenchymal hematoma, 90‐day mRS 0 to 2, or mortality.

Table 4.

Comparison of Treatment Outcomes Between Stent‐Retriever and Contact Aspiration Thrombectomy as the First‐Line Approach in 212 Patients With Acute BAO

| Variables | Stent‐Retriever as the First‐Line Approach (n=145) | Contact Aspiration as the First‐Line Approach (n=67) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion to alternative thrombectomy approach | 32 (22.1%) | 15 (22.4%) | 0.959 |

| Successful reperfusion | 131 (90.3%) | 63 (94.0%) | 0.371 |

| Complete reperfusion | 93 (64.1%) | 41 (61.2%) | 0.679 |

| Hemorrhagic infarction | 30 (20.7%) | 9 (13.4%) | 0.205 |

| Parenchymal hematoma | 7 (4.8%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0.723 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 7 (4.8%) | 0 | 0.100 |

| 90‐d mRS 0 to 2 | 68 (46.9%) | 27 (40.3%) | 0.369 |

| Mortality | 23 (15.9%) | 11 (16.4%) | 0.918 |

Values represent the number of patients (%). BAO indicates basilar artery occlusion; mRS, modified Rankin scale.

Rescue Therapy in Patients With Underlying Severe Basilar Artery Stenosis

Of 55 patients with underlying severe stenosis in the basilar artery, 31 patients underwent intracranial angioplasty with or without stenting (angioplasty group) and 24 patients received intraarterial infusion of tirofiban only (tirofiban group) as a rescue approach. Four patients in the tirofiban group eventually underwent angioplasty because of repeated reocclusions after intraarterial infusion of tirofiban. Overall, successful reperfusion occurred in 89.1% (49/55) of patients. Ninety‐day mRS 0 to 2 was achieved in 49.1% (27/55) of patients. Comparison of treatment outcomes between 2 rescue approaches is presented in Table 5. There were no differences between the 2 groups in the rates of successful reperfusion, good outcome, and hemorrhagic complications.

Table 5.

Outcomes After Endovascular Therapy in 55 Patients With Acute BAO Caused by Underlying Severe Basilar Artery Stenosis

| Outcomes | All Patients (n=55) | Angioplasty With or Without Stenting (n=31) | Intraarterial Infusion of Tirofiban (n=24) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successful reperfusion | 49 (89.1%) | 27 (87.1%) | 22 (91.7%) | 0.686 |

| Complete reperfusion | 33 (60%) | 19 (61.3%) | 14 (58.3%) | 0.824 |

| 90‐d mRS 0 to 2 | 27 (49.1%) | 15 (48.4%) | 12 (50%) | 0.906 |

| Hemorrhagic infarction | 10 (18.2%) | 6 (19.4%) | 4 (16.7%) | 1 |

| Parenchymal hematoma | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0 | 1 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0 | 1 |

| Symptomatic hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | ··· |

Values represent the number of patients (%). BAO indicates basilar artery occlusion; mRS, modified Rankin scale.

Discussion

To our knowledge, to date, this study was the largest to show that modern thrombectomy could provide a high rate of successful reperfusion (91.5%) and a high rate of favorable outcomes (44.8%) in patients with acute BAO. We found that modern thrombectomy was safe for treating acute BAO, with low rates of mortality (13%), symptomatic hemorrhage (1.9%), and procedure‐related complications (4.2%). Moreover, we revealed several significant predictors of 90‐day better outcome after thrombectomy in acute BAO. Finally, we found no difference in treatment outcomes with the stent‐retriever thrombectomy compared with the contact aspiration thrombectomy, as the first‐line approach.

This study investigated real‐world clinical experiences to evaluate the effectiveness of modern endovascular thrombectomy in a large cohort of patients with acute BAO. All 212 patients included were primarily treated with either stent‐retriever thrombectomy (68%) or contact aspiration thrombectomy (32%) within 12 hours of symptom onset. The rate of successful reperfusion (92%) in this study was much higher than the 71% reported in the HERMES (Highly Effective Reperfusion Evaluated in Multiple Endovascular Stroke) trials16 and the pooled 81% (95% CI, 73%–87%) reported in a meta‐analysis by Gory et al, which included 15 studies on the stent‐retriever thrombectomy in patients with acute BAO.5 The high rate of successful reperfusion we observed might be partly because of the extensive experience of the interventionists at high‐volume comprehensive stroke centers. The rate of 90‐day mRS 0 to 2 we observed (45%) was comparable to the 46% reported in the HERMES analysis. This result was also consistent with the previous meta‐analysis by Gory et al. They found a good clinical outcome (mRS 0–2 at 90 days) in 42% of patients.5 Taken together, these findings suggested that modern thrombectomy might be considered the standard of care for eligible patients with acute BAO, despite the lack of a published randomized controlled trial to date.5, 8

Our study also confirmed that endovascular thrombectomy was safe for treating acute BAO, as reported previously for anterior circulation stroke. The rate of symptomatic hemorrhage was only 1.9% in the present study, which was much lower than the 4.4% reported in the HERMES study16 and the 4% reported in the meta‐analysis by Gory et al.5 We also found a low mortality (16%) compared with the pooled estimate rate of 30% in the previous meta‐analysis.5 However, our mortality rate was comparable to that reported in a study on anterior circulation stroke (15.3% in the HERMES study).16 The low rates of symptomatic hemorrhage and mortality in our study might be partly because of the experience of the interventionists and the use of baseline imaging in patient selection. Upon pretreatment diffusion‐weighted imaging, patients who displayed diffuse pontine ischemia were excluded from thrombectomy at all participating centers in the present study. The rate of procedure‐related complications was 4.2% in our study, lower than the 10% reported in a meta‐analysis study by Phan et al.17

Although several studies have described predictors of clinical outcomes after endovascular therapy in patients with posterior circulation stroke, few studies have focused solely on modern thrombectomy in patients with acute BAO. The previously identified factors independently associated with a good outcome after endovascular therapy in posterior circulation stroke included a low baseline NIHSS, successful reperfusion, a history of smoking, a high DWI‐Acute Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS), a shorter time to the start of procedure, a shorter time to reperfusion, better collateral status, and magnetic resonance imaging–based patient selection.3, 7, 9, 18, 19 Recently, Gory et al reported that only the failure to achieve successful reperfusion was an independent predictor of mortality at 3 months, in patients with acute BAO who underwent thrombectomy.20 However, the previous reports had several limitations, including the small numbers of patients included, inclusion of patients treated with older‐generation devices and techniques, inclusion of patients with posterior cerebral artery occlusion, and dichotomized analysis of 90‐day mRS score. In contrast to previous studies, we used the multivariable ordinal logistic regression model to analyze the distribution of the 90‐day mRS outcomes according to potential predictors. It has been suggested that the use of ordinal approaches may be more appropriate than simple dichotomous approaches for analyzing the mRS data.21, 22 We found that younger age, lower baseline NIHSS, absence of diabetes mellitus, and absence of parenchymal hematoma were significantly associated with a favorable shift in the overall distribution of 90‐day mRS scores after endovascular thrombectomy in patients with acute BAO. Successful reperfusion was associated with better outcomes (unadjusted cOR=3.597, P=0.004) in a univariable ordinal regression, but was not a significant predictor in the multivariable analysis in our study.

Our study showed that the stent retriever and contact aspiration as first‐line thrombectomy resulted in similar outcomes, in terms of successful reperfusion, 90‐day mRS 0 to 2, hemorrhagic complications, and mortality. This finding was inconsistent with some previous studies that described different treatment outcomes between these 2 thrombectomy techniques in patients with acute BAO.7, 23, 24, 25 Gory et al analyzed procedural details in 100 patients with BAO and reported that aspiration thrombectomy was superior to stent‐retriever thrombectomy as the first‐line strategy. In that study, contact aspiration achieved a significantly higher rate of complete reperfusion (m‐TICI 3) (54.3% versus 31.5%, P=0.021) and a shorter procedure time (45 minutes versus 56 minutes, P=0.050) than stent‐retriever thrombectomy.25 However, they found similar rates of successful reperfusion and good outcome between the 2 approaches. Similarly, 2 small case series reported that aspiration thrombectomy achieved a higher rate of complete recanalization and a shorter procedure time than stent‐retriever thrombectomy in patients with acute BAO.23, 24 In contrast, Mokin et al found no significant differences in the procedure time, the rate of successful reperfusion, or the rate of good outcomes between the stent‐retriever and aspiration thrombectomy in a cohort of 100 patients with posterior circulation strokes.7 Recently, the ASTER (Contact Aspiration versus Stent Retriever for Successful Revascularization) trial also demonstrated no significant differences between the 2 thrombectomy techniques in the rates of successful and complete reperfusion, embolization to a new vascular territory, and 90‐day mRS 0 to 2, among patients with acute anterior circulation stroke.26 Our results supported the findings of Mokin et al and the ASTER randomized clinical trial, which demonstrated no superiority between the stent‐retriever and contact aspiration techniques for treating emergent large‐vessel occlusion.

Underlying severe stenosis in the target artery can make the thrombectomy procedure more complicated and require additional rescue treatments such as angioplasty with or without stenting and intra‐arterial infusion of antiplatelet drug in patients with acute large vessel occlusions.27 Our study suggests that such rescue treatments are effective and safe for treating underlying severe basilar artery stenosis in patients with acute BAO. Successful reperfusion occurred in 89% and almost half of patients with severe basilar artery stenosis had 90‐day mRS 0 to 2 without symptomatic hemorrhage in our study. When comparing treatment outcomes between patients treated with angioplasty/stenting and those treated with intra‐arterial tirofiban, there were no differences between the 2 groups. Further prospective studies are still warranted to determine the optimal treatment in patients with BAO caused by underlying severe stenosis.

This study had some limitations. The study design was retrospective, based on a prospective database from 3 centers. Thus, patient selection criteria, the baseline imaging study protocol, and the preference for either thrombectomy technique were similar, but not identical, among centers. In addition, radiologic images were not evaluated independently at a core laboratory. Finally, better outcomes of our study compared with previous studies might be because of a selection bias, because patients with extensive pontine infarction on pretreatment diffusion‐weighted imaging were excluded from thrombectomy in our study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study suggested that modern thrombectomy was equally effective and safe for treating patients with acute BAO and patients with anterior circulation stroke. A younger age, a lower baseline NIHSS, and the absence of diabetes mellitus and parenchymal hematoma were significant predictors of better outcomes after thrombectomy in acute BAO. In addition, this study showed no superiority between the stent‐retriever and contact aspiration thrombectomy for treating patients with acute BAO.

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009419 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009419.)

References

- 1. Schonewille WJ, Wijman CA, Michel P, Rueckert CM, Weimar C, Mattle HP, Engelter ST, Tanne D, Muir KW, Molina CA, Thijs V, Audebert H, Pfefferkorn T, Szabo K, Lindsberg PJ, de Freitas G, Kappelle LJ, Algra A; BASICS study group . Treatment and outcomes of acute basilar artery occlusion in the Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): a prospective registry study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mattle HP, Arnold M, Lindsberg PJ, Schonewille WJ, Schroth G. Basilar artery occlusion. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1002–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singer OC, Berkefeld J, Nolte CH, Bohner G, Haring HP, Trenkler J, Gröschel K, Müller‐Forell W, Niederkorn K, Deutschmann H, Neumann‐Haefelin T, Hohmann C, Bussmeyer M, Mpotsaris A, Stoll A, Bormann A, Brenck J, Schlamann MU, Jander S, Turowski B, Petzold GC, Urbach H, Liebeskind DS; ENDOSTROKE Study Group . Mechanical recanalization in basilar artery occlusion: the ENDOSTROKE study. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, Jauch EC, Kidwell CS, Leslie‐Mazwi TM, Ovbiagele B, Scott PA, Sheth KN, Southerland AM, Summers DV, Tirschwell DL, American Heart Association Stroke Council . 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46–e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gory B, Eldesouky I, Sivan‐Hoffmann R, Rabilloud M, Ong E, Riva R, Gherasim DN, Turjman A, Nighoghossian N, Turjman F. Outcomes of stent retriever thrombectomy in basilar artery occlusion: an observational study and systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baek JM, Yoon W, Kim SK, Jung MY, Park MS, Kim JT, Kang HK. Acute basilar artery occlusion: outcome of mechanical thrombectomy with Solitaire stent within 8 hours of stroke onset. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:989–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mokin M, Sonig A, Sivakanthan S, Ren Z, Elijovich L, Arthur A, Goyal N, Kan P, Duckworth E, Veznedaroglu E, Binning MJ, Liebman KM, Rao V, Turner RD IV, Turk AS, Baxter BW, Dabus G, Linfante I, Snyder KV, Levy EI, Siddiqui AH. Clinical and procedural predictors of outcomes from the endovascular treatment of posterior circulation strokes. Stroke. 2016;47:782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Houwelingen RC, Luijckx GJ, Mazuri A, Bokkers RP, Eshghi OS, Uyttenboogaart M. Safety and outcome of intra‐arterial treatment for basilar artery occlusion. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1225–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bouslama M, Haussen DC, Aghaebrahim A, Grossberg JA, Walker G, Rangaraju S, Horev A, Frankel MR, Nogueira RG, Jovin TG, Jadhav AP. Predictors of good outcome after endovascular therapy for vertebrobasilar occlusion stroke. Stroke. 2017;48:3252–3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vergouwen MD, Algra A, Pfefferkorn T, Weimar C, Rueckert CM, Thijs V, Kappelle LJ, Schonewille WJ; Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS) Study Group . Time is brain(stem) in basilar artery occlusion. Stroke. 2012;43:3003–3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang DH, Hwang YH, Kim YS, Park J, Kwon O, Jung C. Direct thrombus retrieval using the reperfusion catheter of the penumbra system: forced‐suction thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:283–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoon W, Jung MY, Jung SH, Park MS, Kim JT, Kang HK. Subarachnoid hemorrhage in a multimodal approach heavily weighted toward mechanical thrombectomy with solitaire stent in acute stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Turk AS, Frei D, Fiorella D, Mocco J, Baxter B, Siddiqui A, Spiotta A, Mokin M, Dewan M, Quarfordt S, Battenhouse H, Turner R, Chaudry I. ADAPT FAST study: a direct aspiration first pass technique for acute stroke thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6:260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larrue V, von Kummer R, Müller A, Bluhmki E. Risk factors for severe hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a secondary analysis of the European‐Australasian Acute Stroke Study (ECASS II). Stroke. 2001;32:438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zaidat OO, Yoo AJ, Khatri P, Tomsick TA, von Kummer R, Saver JL, Marks MP, Prabhakaran S, Kallmes DF, Fitzsimmons BF, Mocco J, Wardlaw JM, Barnwell SL, Jovin TG, Linfante I, Siddiqui AH, Alexander MJ, Hirsch JA, Wintermark M, Albers G, Woo HH, Heck DV, Lev M, Aviv R, Hacke W, Warach S, Broderick J, Derdeyn CP, Furlan A, Nogueira RG, Yavagal DR, Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Bendszus M, Liebeskind DS; Cerebral Angiographic Revascularization Grading (CARG) Collaborators; STIR Revascularization working group; STIR Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI) Task Force . Recommendations on angiographic revascularization grading standards for acute ischemic stroke: a consensus statement. Stroke. 2013;44:2650–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DW, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, Dávalos A, Majoie CB, van der Lugt A, de Miquel MA, Donnan GA, Roos YB, Bonafe A, Jahan R, Diener HC, van den Berg LA, Levy EI, Berkhemer OA, Pereira VM, Rempel J, Millán M, Davis SM, Roy D, Thornton J, Román LS, Ribó M, Beumer D, Stouch B, Brown S, Campbell BC, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Saver JL, Hill MD, Jovin TG; HERMES collaborators . Endovascular thrombectomy after large‐vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta‐analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387:1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Phan K, Phan S, Huo YR, Jia F, Mortimer A. Outcomes of endovascular treatment of basilar artery occlusion in the stent retriever era: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8:1107–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mourand I, Machi P, Nogué E, Arquizan C, Costalat V, Picot MC, Bonafé A, Milhaud D. Diffusion‐weighted imaging score of the brain stem: a predictor of outcome in acute basilar artery occlusion treated with the Solitaire FR device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1117–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoon W, Kim SK, Heo TW, Baek BH, Lee YY, Kang HK. Predictors of good outcome after stent‐retriever thrombectomy in acute basilar artery occlusion. Stroke. 2015;46:2972–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gory B, Mazighi M, Labreuche J, Blanc R, Piotin M, Turjman F, Lapergue B; ETIS (Endovascular Treatment in Ischemic Stroke) Investigators . Predictors for mortality after mechanical thrombectomy of acute basilar artery occlusion. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;45:61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Optimising Analysis of Stroke Trials (OAST) Collaboration , Bath PM, Gray LJ, Collier T, Pocock S, Carpenter J. Can we improve the statistical analysis of stroke trials? Statistical reanalysis of functional outcomes in stroke trials. Stroke. 2007;38:1911–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bath PM, Lees KR, Schellinger PD, Altman H, Bland M, Hogg C, Howard G, Saver JL; European Stroke Organisation Outcomes Working Group . Statistical analysis of the primary outcome in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 2012;43:1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Son S, Choi DS, Oh MK, Hong J, Kim SK, Kang H, Park KJ, Choi NC, Kwon OY, Lim BH. Comparison of Solitaire thrombectomy and Penumbra suction thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke caused by basilar artery occlusion. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8:13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gerber JC, Daubner D, Kaiser D, Engellandt K, Haedrich K, Mueller A, Puetz V, Linn J, Abramyuk A. Efficacy and safety of direct aspiration first pass technique versus stent‐retriever thrombectomy in acute basilar artery occlusion‐a retrospective single center experience. Neuroradiology. 2017;59:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gory B, Mazighi M, Blanc R, Labreuche J, Piotin M, Turjman F, Lapergue B; Endovascular Treatment in Ischemic Stroke (ETIS) Research Investigators . Mechanical thrombectomy in basilar artery occlusion: influence of reperfusion on clinical outcome and impact of the first‐line strategy (ADAPT vs stent retriever). J Neurosurg. 2018. Available at: http://thejns.org/doi/full/10.3171/2017.7.JNS171043. Accessed June 28, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lapergue B, Blanc R, Gory B, Labreuche J, Duhamel A, Marnat G, Saleme S, Costalat V, Bracard S, Desal H, Mazighi M, Consoli A, Piotin M; ASTER Trial Investigators . Effect of endovascular contact aspiration vs stent retriever on revascularization in patients with acute ischemic stroke and large vessel occlusion: the ASTER randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:443–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoon W, Kim SK, Park MS, Kim BC, Kang HK. Endovascular treatment and the outcomes of atherosclerotic intracranial stenosis in patients with hyperacute stroke. Neurosurgery. 2015;76:680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]