Abstract

Background

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is used to estimate pulmonary artery systolic pressure, but an adequate tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TRV) needed to calculate pulmonary artery systolic pressure is not always present. It is unknown whether the absence of a measurable TRV signifies normal pulmonary artery pressure.

Methods and Results

We extracted hemodynamic, TTE, and clinical data from Vanderbilt's deidentified electronic medical record in all patients referred for right heart catheterization between 1998 and 2014. Pulmonary hypertension (PH) was defined as mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥25 mm Hg. We examined the prevalence and clinical correlates of PH in patients without a reported TRV. We identified 1262 patients with a TTE within 2 days of right heart catheterization. In total, 803/1262 (64%) had a reported TRV, whereas 459 (36%) had no reported TRV. Invasively confirmed PH was present in 47% of patients without a reported TRV versus 68% in those with a reported TRV (P<0.001). Absence of a TRV yielded a negative predictive value for excluding PH of 53%. Right ventricular dysfunction, left atrial dimension, elevated body mass index, higher brain natriuretic peptide, diabetes mellitus, and heart failure were independently associated with PH among patients without a reported TRV.

Conclusions

PH is present in almost half of patients without a measurable TRV who are referred for both TTE and right heart catheterization. Clinical and echocardiographic features of left heart disease are associated with invasively confirmed PH in subjects without a reported TRV. Clinicians should use caution when making assumptions about PH status in the absence of a measurable TRV on TTE.

Keywords: echocardiography, hemodynamics, imaging, pulmonary hypertension, right heart catheterization

Subject Categories: Hemodynamics, Pulmonary Hypertension, Echocardiography

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Pulmonary hypertension is a common problem with a high mortality.

It is not known if an absence of measurable tricuspid regurgitation velocity confers an absence of pulmonary hypertension.

In a population of patients referred for right heart catheterization, pulmonary hypertension was present in nearly half (47%) of all patients with an absence of a measurable tricuspid regurgitation velocity.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Clinicians should use caution in patients at risk for pulmonary hypertension with no measurable tricuspid regurgitation velocity by echocardiography.

Right heart catheterization should be pursued when there is clinical concern for pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is defined as a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) ≥25 mm Hg and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in a variety of chronic diseases.1, 2 According to current guidelines and consensus statements, the recommended initial noninvasive method to screen for PH is transthoracic echocardiography (TTE).1, 3 Pulmonary pressure is estimated on TTE by interrogation of the tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TRV) using continuous‐wave Doppler.4, 5 By use of this method, an estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure of >40 mm Hg5 or a TRV of >2.8 m/s1 in the absence of an obvious cause of PH should prompt further evaluation with invasive right heart catheterization (RHC).

Despite decades of echocardiographic and hemodynamic correlation studies in individuals with suspected PH, it is unknown if the absence of a measurable TRV on TTE is associated with the absence of PH by invasive measurement. The prevalence of PH in patients without a measurable TR jet on TTE is also unknown in part because such patients are excluded from correlation studies.6 The absence of a TRV on echocardiography has been equated with an absence of significant PH, and previous studies have suggested that elevated TRV on TTE was sufficient to detect the majority of PH.7, 8, 9 Clinicians would benefit from better information regarding the risk of PH when the screening TTE cannot provide an estimate of pulmonary pressures. In the recent European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society Guidelines, Galie et al suggest evaluating other echocardiographic features if TRV is absent or less than 2.8 m/s if clinical suspicion remains strong, a recommendation made on the basis of expert opinion.1 No prospective or observational data exist to identify which echocardiographic and clinical features are predictive of PH in the absence of a measurable TRV.

We used contemporaneous data from a single large tertiary care center to examine the prevalence, predictive value, and clinical correlates of an absent TRV and invasively confirmed pulmonary pressure in patients referred for both echocardiography and RHC. We hypothesized that the absence of a measurable TRV would be insensitive to exclude PH on catheterization. Although this study may not be generalizable to a community population, addressing this question is highly relevant to symptomatic patients seeking clinical care and to their physicians.

Methods

Study Population

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was waived by the review board. We identified cases within the Vanderbilt Synthetic Derivative, a deidentified mirror image of Vanderbilt's electronic medical record with data on ≈2.5 million patients. The design, implementation, and content of the Synthetic Derivative have been described previously.7, 8 We extracted clinical and hemodynamic data from all adult patients undergoing RHC at Vanderbilt between 1998 and 2014. The method of data extraction has been described in detail elsewhere.9, 10, 11 We included only subjects who underwent a TTE within 2 calendar days before or after RHC. If a subject had multiple RHCs, we only included data from the first procedure in this analysis. Right ventricular (RV) size and systolic function on TTE were graded in a semiquantitative manner (ie, normal, mild, moderate, severe), as previously reported.9 These data were generated from the clinical TTE reports and thus reflect the expert opinion of the interpreting echocardiographer. Quantitative data on RV function (eg, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion) were not available in our cohort. Right atrial pressures were estimated according to guideline statements.5 At our institution, TRV is routinely measured, and all measurements obtained by a technician or reader are transmitted to the echocardiogram report; therefore, absence of a reported TRV is consistent with an unmeasurable signal. Ejection fraction was measured using the biplane Simpson method, and left atrial size was measured as the anterior‐posterior dimension in the parasternal long‐axis view. Images were not reviewed by a core laboratory. Comorbidities were defined by a combination of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) codes and laboratory data in the medical record before RHC or as defined by previously validated algorithms.10 Body mass index was extracted from TTE reports. Patients with inadequate RHC data (defined by the absence of right ventricular and pulmonary arterial pressures) (n=150), acute myocardial infarction (n=264), complex congenital heart disease (n=151), chronic pulmonary embolism (n=18), previous cardiac or lung transplantation (n=362), or profound hemodynamic instability (n=217) were excluded, as previously described.10

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the prevalence of PH on RHC (defined as mPAP ≥25 mm Hg) in subjects without a reported TRV on TTE. We also examined the association between echocardiographic variables and clinical characteristics with prevalent PH.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as mean±standard deviation or frequency (percentage), as appropriate. Clinical characteristics were compared between the TRV and no‐TRV groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and the chi‐squared test for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression models were created to examine the clinical and echocardiographic factors associated with the presence of PH by RHC. Variables were selected a priori based on clinical relevance. This analysis was restricted to those with no reported TRV and no or trace TR. Effect sizes for continuous variables in all models are reported as the difference from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile of our sample, which may provide more clinical insight than differences by standard deviation or single units.

Results

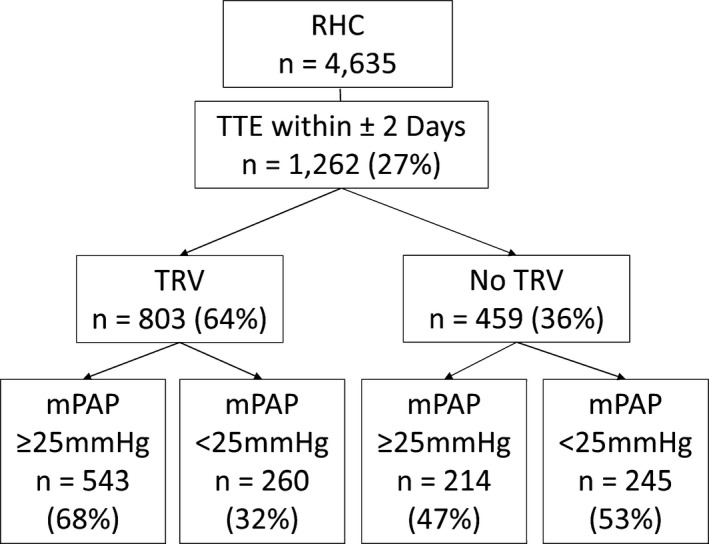

Of 4635 patients referred for RHC, we identified 1262 (27%) who had a TTE within 2 days of RHC who comprised our study sample. In total, 803/1262 (64%) had a reported TRV, whereas 459 (36%) had no reported TRV (Figure 1). Pulmonary hypertension was the indication for RHC in 12% and 4% of the TRV and no‐TRV groups, respectively. Demographic, clinical, hemodynamic, and echocardiographic characteristics of the TRV versus no‐TRV groups are presented in Table. Male sex and higher body mass index were associated with an absent TRV. The prevalence of RV dilation (32% versus 15%) and RV dysfunction (34% versus 17%) was higher in subjects with a reported TRV compared with absent TRV (P<0.001 for both).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study population. mPAP indicates mean pulmonary artery pressure; RHC, right heart catheterization; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram.

Table 1.

Clinical, Echocardiographic, and Hemodynamic Characteristics in Subjects With and Without a Reported Tricuspid Regurgitant Velocity

| No TRV (n=459) | TRV (n=803) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 57 (14) | 60 (16) | 0.007 |

| Male | 260 (57%) | 388 (48%) | 0.004 |

| Race | |||

| Black | 62 (14%) | 121 (15%) | 0.65 |

| White | 377 (82%) | 638 (79%) | |

| Other | 20 (4%) | 44 (6%) | |

| CKD ≥III | 171 (37%) | 353 (44%) | 0.052 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 81 (18%) | 135 (17%) | 0.71 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.3 (7.4) | 28.9 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 78 (17%) | 110 (14%) | 0.11 |

| ILD | 19 (4%) | 41 (5%) | 0.44 |

| Heart Failure | 191 (42%) | 452 (56%) | <0.001 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 537 (843) | 804 (1087) | <0.001 |

| PA mean, mm Hg | 25.7 (11.2) | 33.0 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiographic variables | |||

| RVSP, mm Hg | ··· | 46.6 (19.8) | |

| RV dilation | 34 (15%) | 149 (32%) | <0.001 |

| RV dysfunction | 39 (17%) | 157 (34%) | <0.001 |

| RV hypertrophy | 4 (2%) | 29 (6%) | 0.008 |

| LVIDD, mm | 48.9 (11.2) | 49.9 (12.1) | 0.19 |

| LVIDS, mm | 35.7 (12.9) | 37.1 (14.7) | 0.35 |

| LA diameter, mm | 40.7 (8.9) | 42.4 (9.7) | 0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 46.7 (16.1) | 43.5 (17.7) | 0.011 |

| Hemodynamic variables | |||

| RAP, mm Hg | 7 (4) | 8 (5) | <0.001 |

| mPAP, mm Hg | 26 (11) | 33 (14) | <0.001 |

| PCWP, mm Hg | 14 (8) | 17 (9) | <0.001 |

| PVR, Wood Units | 2.3 (1.9) | 3.6 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| CI, L/(min·m2) | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.0) | <0.001 |

Categorical variables presented as n (%). Continuous variables presented as Mean (standard deviation); echocardiographic measurements presented as millimeters. BMI indicates body mass index; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CI, cardiac index as calculated by the estimated Fick method when available and thermodilution when Fick was not reported; CKD ≥III, chronic kidney disease, stage 3 or worse based on glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ILD, interstitial lung disease; LA, left atrium; LVEF, left‐ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDD, left‐ventricular internal dimension in diastole; LVIDS, left‐ventricular internal dimension in systole; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PA, pulmonary artery; PCWP, mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, mean right atrial pressure; RV, right ventricle; RVSP, right‐ventricular systolic pressure; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity.

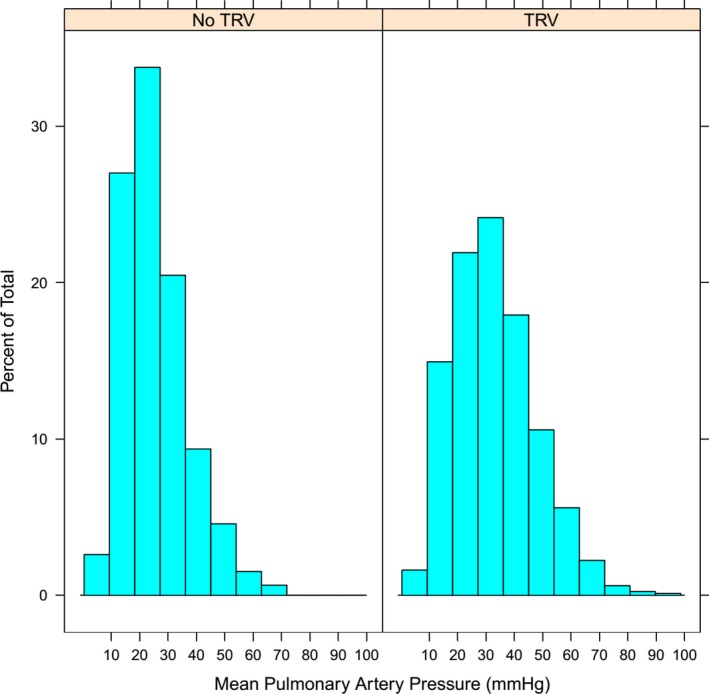

Invasively confirmed PH was present in 47% (214/459) of patients without a reported TRV versus 68% (543/803) of patients with a reported TRV (Figure 1; P<0.001). This finding did not change with shorter intervals between TTE and RHC. PH was present in 46% (178/389) of subjects with no TRV who underwent RHC within 1 calendar day of the TTE and in 47% (64/136) of subjects when TTE and RHC occurred on the same day. Absence of a TRV yielded a negative predictive value for excluding PH of only 53%, a positive predictive value of 68%, sensitivity of 72%, and specificity of 49%. The mPAP in patients with and without a reported TRV was 33±14 mm Hg and 26±11 mm Hg, respectively (P<0.001). The mPAP was >35 mm Hg in 20% of individuals with no measurable TRV (Figure 2). In total, 74% of subjects with PH and no TRV had a pulmonary artery wedge pressure >15 mm Hg. Among the 40 patients with at least mild RV dysfunction or dilation and no TRV, 30 (75%) had PH, yielding a positive predictive value of 75%, a negative predictive value of 50%, a sensitivity of 38%, and a specificity of 84%.

Figure 2.

Distribution of mean pulmonary pressures in those with and without tricuspid regurgitant velocity (TRV) on echocardiogram. Histogram of the distribution of invasive pulmonary pressures stratified by presence or absence of a reported TRV.

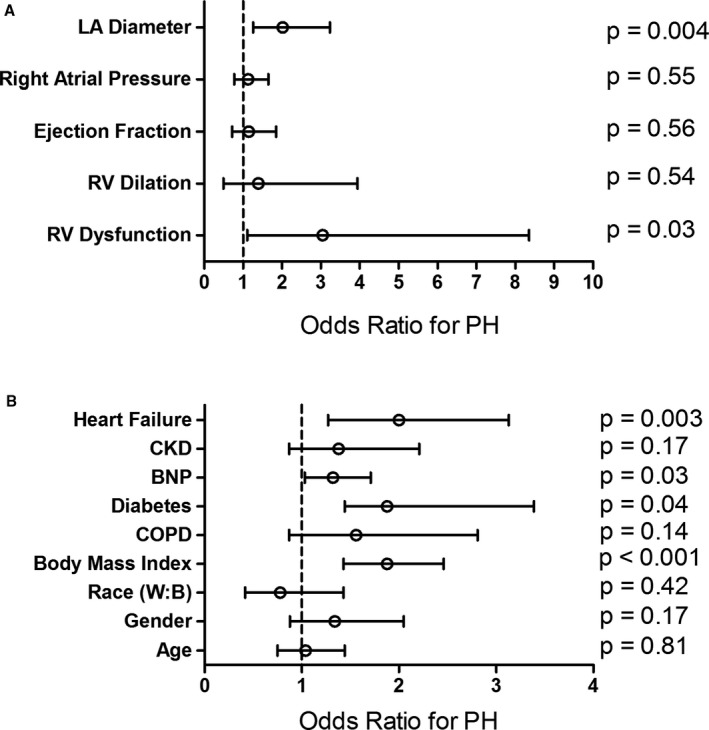

We constructed multivariate models to determine variables associated with PH among subjects with no reported TRV. In a model including echocardiographic variables, left atrial diameter (odds ratio [OR] 2.02; confidence interval [CI] 1.26‐3.23) and RV dysfunction (OR 3.05; CI 1.11‐8.36) were independently associated with PH in the absence of a reported TRV (Figure 3A). In a model including clinical variables (Figure 3B), invasively confirmed PH was associated with higher body mass index (OR 1.88; CI 1.44‐2.46), higher brain natriuretic peptide (OR 1.32; CI 1.03‐1.71), prevalent diabetes mellitus (OR 1.88; CI 1.04‐3.39), and prevalent heart failure (OR 2.00; CI 1.27‐3.13).

Figure 3.

Echocardiographic and clinical features associated with pulmonary hypertension among subjects without a reported tricuspid regurgitant velocity. Multivariate regression analysis of (A) echocardiographic and (B) clinical variables selected a priori based on clinical knowledge. Pulmonary hypertension was associated with left atrial enlargement, right ventricular dysfunction, body mass index, elevated brain natriuretic peptide, and prevalent heart failure. RV dilation and dysfunction were analyzed as binary variables. Any degree of dilation or dysfunction was compared with absence of dilation or dysfunction. Odds ratio for continuous variables represents the difference between the 25th and 75th percentiles. BNP indicates brain natriuretic peptide; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LA, left atrium; PH, pulmonary hypertension; RV, right ventricle.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine whether the absence of a measurable TRV on TTE signified absence of PH in a RHC referral population. We found that invasively confirmed PH is present in nearly half of patients without a reported TRV on TTE who are also referred for RHC. The most common cause of PH in those with no reported TRV in our study was left heart disease (World Health Organization Group II PH). RV dysfunction and increased left atrial size were independently associated with PH in the absence of a TRV, as were established clinical risk factors for PH.

These findings are important to patients and their physicians because they confirm that the lack of a measurable TRV does not signify normal pulmonary pressure. Prior reports have applied this assumption to case‐control studies using PH as an outcome in subjects who did not undergo RHC, which introduces the potential for misclassification.12, 13 Although we cannot know how prevalent this assumption is among clinicians, our study fills a knowledge gap in the literature and provides guidance for which patients require extra caution when an absent TRV is interpreted. Our study also highlights the limitations of estimating pulmonary pressures noninvasively. It is likely that TRV could not be measured in many studies because of poor image quality. This may be partly explained by individuals with a larger chest wall diameter, such as males and obese individuals, who were more likely to have no reported TRV in our cohort.

Patients with no TRV in our study had lower mPAP than those with TRV (26±11 mm Hg versus 33±14 mm Hg). This observation supports the notion that most patients with significant PH will have a measurable TRV. However, 20% of subjects without a TRV had a mPAP >35 mm Hg, which would have remained undetected had they not also been referred for RHC. Moreover, detecting even mild elevations in pulmonary pressure is important based on recent reports showing that “borderline” values of mean pulmonary pressure are reproducibly associated with increased adjusted mortality.14, 15 Additionally, the no‐TRV group may be earlier in the disease process relative to the TRV group and may in fact develop more readily measurable TRV Doppler signals over time.

We identified echocardiographic and clinical features that serve as circumstantial evidence to raise or lower suspicion for prevalent PH. Our data indicate that left atrial remodeling and RV dysfunction are strongly associated with PH and should raise suspicion for this diagnosis in the absence of a TRV. Additional studies are needed with more detailed echocardiographic data to examine whether more sensitive measures of RV function or other evidence of PH (eg, flattening) add specificity for a diagnosis of PH in the absence of a measurable TRV. Our logistic regression analysis confirmed that clinical features previously associated with PH such as obesity and diabetes mellitus are associated with PH in the absence of a reported TRV. Our data also confirm previous findings that prevalent HF or elevation of a biochemical marker of HF severity (eg, brain natriuretic peptide) was associated with increased pulmonary pressure. This is a known association, and thus, in this population, the clinician must be cautious when interpreting TTE results with an absent TRV.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The data presented were obtained from a single center, although our cohort is sex balanced and 15% of subjects are black. This analysis was performed on a population of patients who were referred for an RHC and are thus more likely to have a higher prevalence of PH compared with the general population. A summary of RHC indications by group is provided in Table S1. Although referral bias is unavoidable in electronic health record cohorts, the “real world” data we present are used to make management decisions every day. We are unable to comment on whether the presence or absence of a TRV influenced the decision to refer a patient for RHC. However, we also included subjects who underwent echocardiography within 2 days after RHC, which somewhat mitigates indication bias. We are unable to manually review the RHC tracings for the accuracy of the computer‐generated pressure values, although we have previously reported that this difference is likely to be small in our population.10 A small minority of TTE studies performed at our institution are “limited” studies in which a full interrogation of the TRV may not have been attempted. Given the small number of these studies, it is unlikely they would have influenced our study's conclusions. The TTE data were obtained within 2 days (before or after) of the RHC and not concurrently. It is possible that inherent lability and/or interventions occurring between studies (eg, diuresis) could have influenced our findings; however, our observations held true at shorter intervals (within 1 day and same‐day measurement), and any intervention would be likely to lower pulmonary pressure, which would reduce the number of subjects with PH. Finally, a 2‐day interval is shorter than previously reported intervals between TTE and RHC in which pulmonary pressure measurements achieved a high degree of correlation.6

Conclusion

The absence of a TRV on TTE does not reliably exclude PH in patients referred for RHC. In patients with suspected PH, invasive assessment should be considered in patients without a reported TRV in the presence of RV dysfunction.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH #1 U01 HL125212‐01 to Dr Hemnes, American Heart Association Fellow to Faculty Grant #13FTF16070002, Pulmonary Hypertension Association Proof‐of‐Concept Award, Actelion Entelligence Young Investigator Award, and Gilead PAH Scholars Award Program to Dr Brittain, NIH # 5T32HL087738‐08 to Dr Assad. The data set used in the analyses described was obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Centers BioVU, which is supported by institutional funding and by the Vanderbilt CTSA grant UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Indications for Right Heart Catheterization by Group

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009362 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009362.)

References

- 1. The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) , Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery J‐L, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simonneau G, Galiè N, Rubin LJ, Langleben D, Seeger W, Domenighetti G, Gibbs S, Lebrec D, Speich R, Beghetti M, Rich S, Fishman A. Clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:5S–12S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Farber HW, Lindner JR, Mathier MA, McGoon MD, Park MH, Rosenson RS, Rubin LJ, Tapson VF, Varga J. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119:2250–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zoghbi WA, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:777–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713; quiz 786–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greiner S, Jud A, Aurich M, Hess A, Hilbel T, Hardt S, Katus HA, Mereles D. Reliability of noninvasive assessment of systolic pulmonary artery pressure by Doppler echocardiography compared to right heart catheterization: analysis in a large patient population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001103 DOI: 10.1161/jaha.114.001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bowton E, Field JR, Wang S, Schildcrout JS, Van Driest SL, Delaney JT, Cowan J, Weeke P, Mosley JD, Wells QS, Karnes JH, Shaffer C, Peterson JF, Denny JC, Roden DM, Pulley JM. Biobanks and electronic medical records: enabling cost‐effective research. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:234 cm3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wells QS, Farber‐Eger E, Crawford DC. Extraction of echocardiographic data from the electronic medical record is a rapid and efficient method for study of cardiac structure and function. J Clin Bioinforma. 2014;4:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Assad TR, Hemnes AR, Larkin EK, Glazer AM, Xu M, Wells QS, Farber‐Eger EH, Sheng Q, Shyr Y, Harrell FE, Newman JH, Brittain EL. Clinical and biological insights into combined post‐ and pre‐capillary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2525–2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Assad TR, Brittain EL, Wells QS, Farber‐Eger EH, Halliday SJ, Doss LN, Xu M, Wang L, Harrell FE, Yu C, Robbins IM, Newman JH, Hemnes AR. Hemodynamic evidence of vascular remodeling in combined post‐ and precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2016;6:313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brittain EL, Chan SY. Integration of complex data sources to provide biologic insight into pulmonary vascular disease (2015 Grover Conference Series). Pulm Circ. 2016;6:251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, Shizukuda Y, Plehn JF, Minter K, Brown B, Coles WA, Nichols JS, Ernst I, Hunter LA, Blackwelder WC, Schechter AN, Rodgers GP, Castro O, Ognibene FP. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:886–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Machado RF, Barst RJ, Yovetich NA, Hassell KL, Kato GJ, Gordeuk VR, Gibbs JSR, Little JA, Schraufnagel DE, Krishnamurti L, Girgis RE, Morris CR, Rosenzweig EB, Badesch DB, Lanzkron S, Onyekwere O, Castro OL, Sachdev V, Waclawiw MA, Woolson R, Goldsmith JC, Gladwin MT; walk‐PHaSST Investigators and Patients . Hospitalization for pain in patients with sickle cell disease treated with sildenafil for elevated TRV and low exercise capacity. Blood. 2011;118:855–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Assad TR, Maron BA, Robbins IM, Xu M, Huang S, Harrell FE Jr, Farber‐Eger EH, Wells QS, Choudhary G, Hemnes AR, Brittain EL. Prognostic effect and longitudinal hemodynamic assessment of borderline pulmonary hypertension. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1361–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maron BA, Hess E, Maddox TM, Opotowsky AR, Tedford RJ, Lahm T, Joynt KE, Kass DJ, Stephens T, Stanislawski MA, Swenson ER, Goldstein RH, Leopold JA, Zamanian RT, Elwing JM, Plomondon ME, Grunwald GK, Barón AE, Rumsfeld J, Choudhary G. Association of borderline pulmonary hypertension with mortality and hospitalization in a large patient cohort: insights from the VA‐CART program. Circulation. 2016;133:1240–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Indications for Right Heart Catheterization by Group