Abstract

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy continues to be a significant cause of death or neurodevelopmental delays despite standard use of therapeutic hypothermia. The use of stem cell transplantation has recently emerged as a promising supplemental therapy to further improve the outcomes of infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. After the injury, the brain releases several chemical mediators, many of which communicate directly with stem cells to encourage mobilization, migration, cell adhesion and differentiation. This manuscript reviews the biomarkers that are released from the injured brain and their interactions with stem cells, providing insight regarding how their upregulation could improve stem cell therapy by maximizing cell delivery to the injured tissue.

Keywords: brain-derived neurotrophic, hypoxia inducible, erythropoietin, factor, matrix metalloproteinase, neonatal, stromal cell-derived, vascular endothelial growth

Introduction

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) affects between 1 and 8 per 1000 live births in the United States each year, and up to 26 per 1000 live births in developing countries (Kurinczuk et al., 2010). Despite the standard use of therapeutic hypothermia, moderate to severe HIE continues to result in death or significant neurodevelopmental delays in 40–50% of patients (Douglas-Escobar and Weiss, 2015; Parikh and Juul, 2018). The use of stem cell transplantation has recently emerged as a promising supplemental therapy to further improve the outcomes of infants with HIE.

A recent pilot study assessing infants with HIE treated with hypothermia plus autologous umbilical cord blood (UCB) versus infants treated with hypothermia alone demonstrated that 74% of the UCB-treated infants survived to one year with Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development III scores ≥ 85 versus 41% of the infants receiving hypothermia alone (Cotten et al., 2014). The study size was small, but it was the first to demonstrate feasibility and short-term safety of UCB transplantation in this population. Although UCB transplantation has shown promise in this population, and the use of UCB avoids the ethical concerns that are raised by the use of fetal stem cells, the availability of trained staff to safely and successfully collect UCB is often limited. In addition to access concerns, the risk profile of UCB transplantation has not been fully evaluated (Ballen, 2017).

As with any new therapy, the promise of stem cell transplantation to improve outcomes of neonatal HIE carries with it the need to establish the underlying mechanisms of action. Several recent studies have demonstrated that the upregulation or overexpression of factors on exogenous stem cells prior to injection can improve their migration and therapeutic effect in models of lung injury, liver failure, limb ischemia, and stroke (Cui et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Xiang et al., 2017; Jimenez et al., 2018). As demonstrated by these studies, understanding the signaling mechanisms between the injured tissue and the stem cells may provide the opportunity to modify the signals through manipulation of the exogenous stem cells, allowing for improved efficacy and safety. As the types of active factors vary over time, therapies utilizing modified stem cell expression may take advantage of these variations to allow for different treatment approaches depending on the phase of injury.

Endogenous mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been found to mobilize into the peripheral circulation after tissue ischemia. After mobilization, or when exogenous cells are transplanted, the cells must then migrate to the injured tissue. At the site of the injured tissue, the MSCs aid in tissue repair via paracrine mechanisms, local progenitor cell proliferation, and/or directly undergo adhesion and integration into the injured tissues (Deng et al., 2011; Rennert et al., 2012). In this paper, we review the biomarkers that have been found to be elevated in HIE (summarized in Table 1), and evaluate their roles in the mobilization, migration, cell adhesion, and proliferation of stem cells. Altering the ability of exogenous stem cells to home to injured tissue by manipulating their expression profiles could potentially improve the safety and efficacy of exogenous stem cell transplantation for neonatal brain injury.

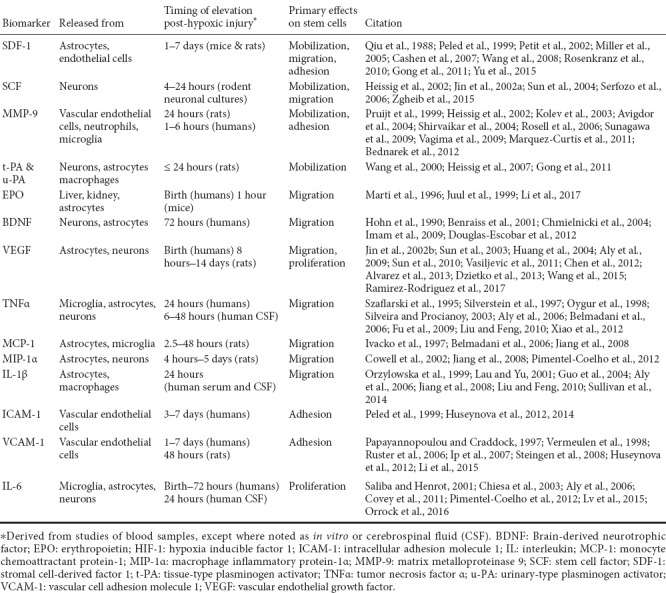

Table 1.

Key features of the factors elevated after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury

Stem Cell Mobilization

Stem cells are localized in microenvironments known as “niches” that exist throughout the body, including the bone marrow (BM), where stem cells are maintained in undifferentiated and self-renewable states. Stem cell mobilization is the process by which stem cells are released from these niches into the peripheral circulation. Although transplanted stem cells do not require mobilization, as they are commonly injected directly into the circulation, the process of mobilization is discussed here to support the possibility that upregulation of certain factors on the transplanted cells could lead to increased mobilization of endogenous cells. This would be especially important in allogeneic transplants, to attempt to minimize the dose of foreign cells that would need to be used.

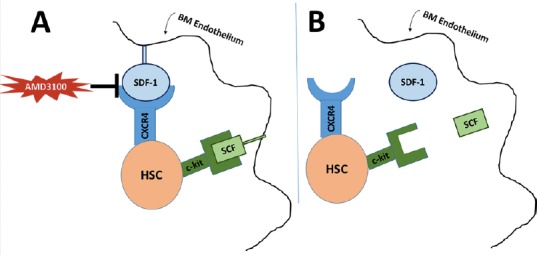

There are several signaling molecules involved in maintaining stem cells in niches that can be modified to allow for stem cell mobilization. Most of the research on these signaling molecules has been done in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) lines, and there remains a paucity of data on mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) niches. Because of this, much of the data presented in this section will represent studies in HSCs, with the likelihood that many of these signaling mechanisms may similarly affect MSCs. Two receptors involved in stem cell mobilization include CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) and c-kit. CXCR4 and c-kit are expressed by HSCs and bind to stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and stem cell factor (SCF), respectively, on the BM endothelium (Figure 1). In addition, both MMP-9 and plasminogen activators (PAs) have been found to be elevated after neonatal HIE and are factors involved in the process of stem cell mobilization (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Receptor-ligand binding to maintain hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) quiescent in the bone marrow niche.

(A) HSCs are maintained in the bone marrow niche through molecular interactions including CXCR4 binding to SDF-1 and c-kit binding SCF. AMD3100 is a CXCR4 antagonist which induces stem cell mobilization. (B) When these interactions are disrupted, SDF-1 and SCF are released and HSCs are mobilized. CXCR4: CXC chemokine receptor 4; HSC: hematopoietic stem cell; SCF: stem cell factor; SDF-1: stromal cell-derived factor 1.

Figure 2.

Stem cell mobilization.

†G-SCF causes stem cell mobilization through direct plasminogen-mediated downregulation of SDF-1 and MMP-9 dependent release of SCF. ‡Tissue and urinary plasminogen activators promote MMP-9 mediated release of SCF and decrease SDF-1 levels in the bone marrow. ◊SDF-1 and VEGF stimulate release of pro-MMP-9 which results in increased SCF and stem cell mobilization. *Aprotinin is a plasminogen inhibitor which consequently inhibits MMP-9 activation and stem cell mobilization. G-CSF: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MMP-9: matrix metalloproteinase 9; SCF: stem cell factor; SDF-1: stromal cell-derived factor 1; t-PA: tissue-type plasminogen activator; u-PA: urinary-type plasminogen activator; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

SDF-1 or CXCL12

SDF-1 is a member of the CXC chemokine family that is primarily released by bone marrow stromal cells and is a key component in stem cell mobilization (Matthys et al., 2001). After hypoxic-ischemic injury, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) increases the gene expression of SDF-1 (Ceradini et al., 2004). SDF-1 release by the astrocytes and endothelial cells is proportionate to the level of hypoxia and is elevated one to seven days following HIE. The time to peak concentration appears to vary depending on the model used, between about three days after injury in neonatal mice and seven days after injury in neonatal rats (Miller et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2015).

Human BM endothelium constitutively expresses SDF-1 which binds to the CXCR4 receptor on the cell surface of CD34+ stem cells (Figure 1) (Peled et al., 1999). A reduction in the SDF-1 concentration within the bone marrow niche results in mobilization of stem cells despite stimulating upregulation of the BM CXCR4 receptors (Petit et al., 2002). Although both of the previous studies assessed HSCs, several studies have also investigated the role of SDF-1 in MSCs. CXCR4 expression has been shown to be upregulated in MSCs pretreated with SDF-1 as well as after hypoxic conditions (Yu et al., 2015). Additionally, inhibition of CXCR4 increased the number of circulating MSCs in a mouse model of bone injury (Kumar and Ponnazhagan, 2012).

SCF

SCF (a.k.a. steel factor, kit ligand, mast cell growth factor) is a hemopoietic cytokine that binds to the tyrosine kinase receptor c-kit (Qiu et al., 1988). SCF in the bone marrow niche binds to c-kit on stem cells to maintain their quiescent state, and when SCF is solubilized and the bond is disrupted, stem cells are mobilized. SCF and c-kit expression are elevated throughout development and adulthood in neural cells, hematopoietic stem cells, and germ cells (Matsui et al., 1990; Motro et al., 1991; Manova et al., 1992), and SCF is involved in the regulation of the activity of astrocytes, oligodendroglia, and microglia (Ida et al., 1993; Zhang and Fedoroff, 1997, 1999). SCF expression is upregulated in central nervous system injury and inflammation, and has been found to be increased 4 to 24 hours after hypoxic injury in rodent forebrain neuronal cultures (Jin et al., 2002a). One of the factors leading to the release of soluble SCF is matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, which induces HSC mobilization and hematopoietic recovery through its effects on SCF (Heissig et al., 2002).

MMP-9

Matrix metalloproteinases are enzymes primarily responsible for degradation of extracellular matrix proteins, but also release ligands, inactivate cytokines, and cleave receptors (Van Lint and Libert, 2007). MMP-9 is a protease produced by vascular endothelial cells, infiltrated neutrophils, and activated microglia in ischemic brain (Kolev et al., 2003; Rosell et al., 2006). Levels of MMP-9 are elevated in HIE, with increased levels corresponding to increased severity of HIE (Sunagawa et al., 2009; Bednarek et al., 2012). Similar to SDF-1, MMP-9 levels appear to vary by species, as they can be elevated in adult mice as early as 4 hours after the hypoxic event (Gasche et al., 1999), but in a neonatal rat model, the levels did not increase until 24 hours post-hypoxic injury (Adhami et al., 2008).

In human neonates, MMP-9 has been found elevated up to six hours after birth, with higher levels in asphyxiated neonates with neurologic sequela compared to those without neurologic sequela. This significant difference in MMP-9 level resolved by day 1 of life, suggesting that MMP-9 may play an early role in humans (Sunagawa et al., 2009). In the later phases of recovery, MMPs appear to take on more beneficial roles. MMP-9 was found to be elevated 7–14 days after stroke in a rat model, and inhibition of MMP in this model caused suppression of neurovascular remodeling, impaired functional recovery, and increased brain injury (Cunningham et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2006; Yang and Rosenberg, 2015). MMP-9 may have limitations as a biomarker of HIE in premature infants, as plasma MMP-9 levels are significantly lower in infants born at 25–27 weeks gestation (Bednarek et al., 2012).

MMP-9 also functions in promoting release of extracellular matrix-bound or cell-surface-bound cytokines that activate stem cell mobilization. One of these cytokines is SCF, as MMP knockout mice demonstrate significantly lower levels of SCF than wildtype. Additionally, MMP-9 has been shown to induce HSC mobilization via interleukin (IL)-8 in non-human primates (Pruijt et al., 1999). Conversely, MMP-9 can be upregulated by other factors that are active in stem cell regulation, such as SDF-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulate release of pro-MMP-9, resulting in increased SCF plasma levels and mobilization of CD34+ stem cells (Heissig et al., 2002).

PAs

Plasmin is a serine protease that acts in fibrinolysis, extracellular matrix degradation, and activation of MMPs, and may further brain damage in ischemic injury via extracellular proteolysis and cell degradation (Oranskii et al., 1977; Junge et al., 2003). Tissue-type and urinary-type PAs (t-PA & u-PA) are elevated after injury in a rat model of neonatal cerebral hypoxia (Adhami et al., 2008). This may be unique to neonatal hypoxic injury, as the same study demonstrated that elevations of t-PA and u-PA concentrations were not observed in adult rats after the same injury. Although PA concentrations increase in the first four hours after injury, corresponding to the increased fibrin deposition seen, t-PA and u-PA levels remain elevated well beyond that period, up to 24 hours after injury. Due to expression of t-PA and u-PA by macrophages and astrocytes outside of the vasculature, it has been suggested that the prolonged period of elevation may result in plasmin-mediated cytotoxicity. Supporting this theory, investigators have demonstrated that plasmin inactivation by alpha-2-antiplasmin within two hours of hypoxic-ischemic (HI) injury leads to a dose-dependent decrease in brain injury after 1 week, and t-PA knockout mice have a 69% increase in short term mortality after HI injury. Additionally, increase HIE-associated brain damage was seen with ventricular injection of t-PA (Adhami et al., 2008). Similar to MMP-9, plasmin’s pro-injury roles in HIE may be balanced by its involvement in stem cell mobilization. Plasmin is closely related to MMP-9, as activation of plasminogen and the fibrinolytic cascade promotes MMP-mediated release of SCF (Heissig et al., 2007). Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is also involved in this pathway, as G-CSF induces HSC mobilization via direct plasminogen-mediated downregulation of SDF-1 and an MMP-9 dependent upregulation of SCF (Heissig et al., 2002; Gong et al., 2011). Further, a plasminogen antagonist, aprotinin, inhibited G-CSF induced HSC mobilization and MMP-9 activation (Gong et al., 2011) (Figure 2).

Stem Cell Migration

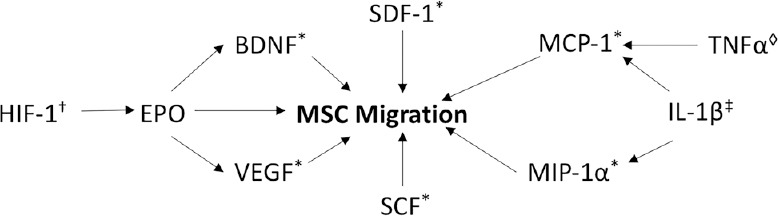

Once stem cells are released from the BM niche into peripheral circulation, they must then migrate to the specific areas of the body where they are needed. Figure 3 demonstrates several of the factors that have been found to be elevated after HIE and are involved in stem cell migration, and Figure 4 illustrates the MSC receptors involved in migration and their corresponding ligands.

Figure 3.

Stem cell migration.

†HIF-1 induces expression of EPO. EPO causes MSC migration through an EPO receptor on MSCs and through increasing levels of VEGF and BDNF. ‡IL-1β released at the injured site in HIE causes secretion of MCP-1 and MIP-1α. ◊TNFα causes MCP-1 dependent migration of neural progenitor cells. *SDF-1, SCF, BDNF, MCP-1, and MIP-1α all induce migration of MSCs. BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; EPO: erythropoietin; HIF-1: hypoxia inducible factor 1; IL-1β: interleukin 1β; MCP-1: monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIP-1α: macrophage inflammatory protein-1α; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; SCF: stem cell factor; SDF-1: stromal cell-derived factor 1; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor α; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

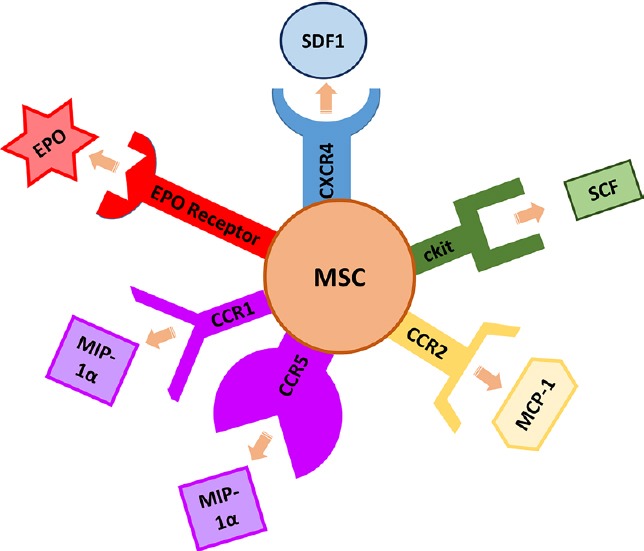

Figure 4.

Chemotactic ligands at the site of injured tissues and stem cell receptors involved in migration.

EPO: erythropoietin; MCP-1: monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIP-1α: macrophage inflammatory protein-1α; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; SCF: stem cell factor; SDF-1: stromal cell-derived factor 1.

Erythropoietin (EPO)

EPO is best known for its role in the regulation of erythropoiesis (Erslev, 1953); however, it also has protective and reparative abilities in the heart (Teixeira et al., 2012), spinal cord (Xiong et al., 2011), bone (Chen et al., 2014), kidneys (Liu et al., 2013), and brain (Khairallah et al., 2016). EPO has been found to upregulate VEGF and angiogenesis, serve as a direct angiogenic factor, inhibit apoptosis, increase differentiation of MSCs, and mobilize endothelial progenitor cells (Ribatti et al., 1999; Heeschen et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2014). EPO is primarily secreted by the kidney, but can also be released by astrocytes, and is elevated in neonatal HIE. The highest plasma and CSF levels of EPO are found right after hypoxic injury (Marti et al., 1996; Juul et al., 1999), and its release is in part due to HIF-1-induced upregulation (Prass et al., 2003). EPO may also induce MSC migration and facilitate angiogenesis via the EPO receptor expressed on human MSCs (Zwezdaryk et al., 2007) (Figure 4). In a rat model of spinal cord injury, EPO was demonstrated to increase migration of transplanted bone marrow MSCs to site of injury, increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and VEGF expression, decrease neuronal apoptosis at the injury site, and hasten clinical neurologic recovery at 28 days post injury compared to both sham treatment and treatment with stem cells alone (Li et al., 2017).

Given the studies suggesting EPO may have a role in both neuroprotection and MSC migration, several investigators have begun assessing the effects of exogenous EPO administration on neonatal HIE (Parikh and Juul, 2018). Although the doses and intervals have varied, multiple clinical studies have now demonstrated that EPO administered immediately after HI injury, and in combination with therapeutic hypothermia, decreases seizure activity and endogenous nitric oxide production, and results in improved neurodevelopmental outcomes or death at 6-18 months of age (Zhu et al., 2009; Elmahdy et al., 2010). Additionally, EPO combined with therapeutic hypothermia results in lower brain injury on MRI and improved motor scores at 1 year of age over control infants who received hypothermia and placebo (Wu et al., 2016). Additional large multi-center studies are ongoing, with high-dose erythropoietin for asphyxia and encephalopathy (HEAL) hoping to recruit 500 newborns in the United States (Kawahara et al., 1997) and EPO for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in newborns (PAEAN) hoping to recruit 300 newborns in Australia (Plumier et al., 1997).

SDF-1

In addition to stem cell mobilization, SDF-1 also plays a role in migration of stem cells to sites of injury. In a rat model of cerebral hypoxia, SDF-1 was found to be highly expressed at lesion sites in the hippocampus, corpus callosum, and periventricular areas, correlating with the sites of human UCB stem cell migration after intraperitoneal injection. Additionally, administration of an SDF-1 inhibitor resulted in a decrease in the number of UCB cells found in the lesioned areas of the brain (Rosenkranz et al., 2010). Similarly, treatment with a CXCR4 antagonist, AMD3100, also prevents MSC migration to HI-injured brain (Wang et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2015). Because AMD3100 also inhibits interaction of CXCR4 with SDF-1 within the bone marrow, administration results in more stem cells mobilized into peripheral circulation, but those stem cells have decreased migration to specific sites along the SDF-1 gradient (Figure 1) (Cashen et al., 2007). Likely related to its role in stem cell mobilization, intracranial administration of SDF-1 decreased intracranial inflammation, induced cerebral re-myelination, and improved memory and spatial perception in a neonatal mouse model of cerebral hypoxia (Mori et al., 2015).

SCF

Much like SDF-1, SCF also plays dual roles in both stem cell mobilization and migration. Although SCF’s role in stem cell migration has been demonstrated in neural progenitor cells (NPC) in several other types of injury, there is a paucity research assessing this factor’s effects on MSCs and after hypoxic brain injury. In a mouse model of hypothermic injury, Sun et al demonstrated upregulated gene and protein levels of SCF in injured areas of the brain, which induced NPC migration (Sun et al., 2004). Additionally, recombinant SCF induced migration of mouse embryonic stem cells after neural induction (Serfozo et al., 2006). In non-neural tissues, SCF is also activated in injury and has been shown to enhance diabetic wound healing in mice through skin stem cell migration and increases in expression of HIF-1 and VEGF (Zgheib et al., 2015).

BDNF

BDNF is secreted by neurons and astrocytes in the central nervous system and plays an important role in neuronal maintenance and survival (Hohn et al., 1990). Mice born without the tyrosine kinase receptor for BDNF do not feed normally and display neuronal deficiencies in their facial motor nucleus, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system (Klein et al., 1993). BDNF levels from cord blood and serum samples taken in the first few days of life are higher in full term infants versus premature infants, reflecting advancing maturity of the nervous and immune system (Malamitsi-Puchner et al., 2004). BDNF may also play a role in brain injury, as it is found at increased levels in the serum after HIE. Elevated BDNF levels at 72 hours of life in term newborns with HIE is a poor prognostic factor and suggests severe brain injury (Imam et al., 2009).

BNDF, as well as other neurotrophins, has been shown to increase migration of multipotent astrocytic stem cells in vitro and neuronal cells in vivo (Benraiss et al., 2001; Chmielnicki et al., 2004; Douglas-Escobar et al., 2012). It stimulates migration of stem cell progenitors in the cerebellum, and while BNDF knockout granule cells lack the ability to migrate appropriately, administration of exogenous BDNF restores their ability to migrate out of the external granule cell layer (Borghesani et al., 2002). Additionally, BNDF has been shown to be neuroprotective in a neonatal rat model of hypoxic-ischemic injury, likely via activation of the extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) pathways (Han and Holtzman, 2000). A single intraventricular injection of BDNF decreased hypoxia-ischemia induced brain tissue loss in a 7-day old rat model by 90% when injected prior to injury and by 50% when injected after the insult. Less protection was seen after injection in 21 day old rats, indicating more robust BDNF effects in the more immature brain (Cheng et al., 1997).

VEGF

VEGF plays a role in regulating both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis and is vital for brain development (Millauer et al., 1993). VEGF mediates neuronal growth and maturation in the CNS through binding the VEGFR2 receptor (Khaibullina et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2006), and is a key component in exercise-induced hippocampal neurogenesis (Fabel et al., 2003). VEGF is secreted by astrocytes and neurons (Alvarez et al., 2013), and has been found to be elevated in both the CSF and serum in human neonates with HIE (Aly et al., 2009; Vasiljevic et al., 2011). VEGF is elevated immediately following HI injury in human neonates (Aly et al., 2009) and remains elevated for up 14 days in a neonatal rat model of HI brain injury (Huang et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2012). Studies have shown that CSF levels of VEGF in human neonates correlate with severity of HIE, however correlation of serum levels with severity have demonstrated mixed results (Ergenekon et al., 2004; Aly et al., 2009).

In addition to VEGF’s role in angiogenesis during hypoxia, it also increases NPC migration in response to interaction with VEGF receptor 2 (Ramirez-Rodriguez et al., 2017). Although VEGF stimulates migration of stem cells in a dose dependent manner in vitro, in vivo studies have been unable to show this phenomenon with VEGF signaling alone (Schmidt et al., 2005). VEGF also induces migration of MSCs, although the increased migration appears to be associated with decreased MSC differentiation (Wang et al., 2015).

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)

TNFα is a pro-inflammatory cytokine with roles in cell signaling during acute inflammatory states (Old, 1985; Havell, 1987), but also affects sleep regulation and embryonic development (Wride and Sanders, 1995; Krueger et al., 1998). In brain injury, TNFα is released from microglia, astrocytes, and neurons (Silverstein et al., 1997) and is involved in neuronal apoptosis and disruption of the blood brain barrier. Intracranial TNFα levels have been found elevated 4–24 hours post HI injury in neonatal rats (Szaflarski et al., 1995), and CSF levels have been found to peak at 6 hours post HI injury in human neonates (Oygur et al., 1998; Silveira and Procianoy, 2003). Serum TNFα levels in humans can be significantly elevated within 24 hours of injury (Oygur et al., 1998; Silveira and Procianoy, 2003; Aly et al., 2006; Liu and Feng, 2010).

High levels of TNFα are likely neurotoxic; however, some studies suggest TNFα at lower levels may have neuroprotective effects. Despite studies demonstrating that elevated TNFα levels worsen neuropathological outcomes after nitric oxide-induced neurotoxicity (Blais and Rivest, 2004), mice completely lacking TNFα activity demonstrate increased neuronal injury after nitric oxide-induced brain damage, as well as decreased early microglial activation (Turrin and Rivest, 2006). Additionally, exposure of neonatal mouse subventricular zone stem cells to low levels of TNFα (1 ng/mL) causes neuronal differentiation and stem cell proliferation, while higher levels of TNFα (10–100 ng/mL) causes apoptosis of the stem cells (Bernardino et al., 2008). The increased migration of neural progenitor cells induced by TNFα appears to act through several mediators. One study showed that migration is inhibited in monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) knockout mice (Belmadani et al., 2006), while others showed migration through upregulation of intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 (Fu et al., 2009) and vascular cell adhesion protein (VCAM)-1 expression (Xiao et al., 2012).

MCP-1/macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α)

MCP-1, also called CCL-2, was the first member of the C-C chemokine family discovered in humans, and its primary action is to induce chemotaxis of monocytes, memory T cells, and natural killer cells (Van Coillie et al., 1999; Deshmane et al., 2009). MIP-1α, also called CCL3, is also a C-C chemokine which plays a role in the chemotaxis of neutrophils, macrophages and T cells (Taub et al., 1993; Koch et al., 1994). MCP-1 and MIP-1α both appear to have similar chemotactic effects in stem cell migration, promoted via MCP-1 binding to receptor CCR2 and MIP-1α binding to CCR1 and CCR5 on the surface of stem cells (Belmadani et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2008). MCP-1 levels are increased 2.5 to 48 hours after HI injury (Ivacko et al., 1997), while MIP-1α is released by astrocytes and neurons with levels elevated 4 hours to 5 days after HI injury (Cowell et al., 2002; Pimentel-Coelho et al., 2012).

IL-1β

IL-1β is a member of the interleukin 1 cytokine family produced by activated macrophages. It is an inflammatory mediator involved in cellular apoptosis, differentiation, and proliferation (No authors listed, 2018). IL-1β is also highly expressed in prenatal and postnatal brain development and guides radial migration of neural progenitors in rat neocortex development (Dziegielewska et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2014). Astrocytes release IL-1β during the acute phase of HIE (Orzylowska et al., 1999; Lau and Yu, 2001), and levels are elevated in both the CSF and serum of human neonates within 24 hours post HI-injury (Aly et al., 2006). Elevated levels predict poor prognosis in HIE, as up to 88% of patients with elevated IL-1β post HIE have abnormal neurologic outcomes at 6 months of age (Aly et al., 2006; Liu and Feng, 2010).

When expression of IL-1β is inhibited, MIP-1α expression is also inhibited, and it has been hypothesized that IL-1β release at the site injured in HIE may initiate astrocytes, microglia, and neurons to secrete MCP-1 and MIP-1α (Guo et al., 2004; Jiang et al., 2008). Whether through the activation of MCP-1 and MIP-1α, or other pathways, it has been shown that pre-stimulation with IL-1β increases migration of murine MSCs in a dose-dependent manner (Sullivan et al., 2014).

Stem Cell Adhesion

Once stem cells migrate to target tissues, molecules involved with cell adhesion allow the stem cells to adhere to other cells or the extracellular matrix surrounding them. The main HIE biomarkers that have roles in stem cell adhesion are ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and MMPs.

ICAM-1 & VCAM-1

ICAMs and VCAMs are expressed on vascular endothelial cells and have roles in leukocyte attachment and trans-endothelial migration at inflammatory sites through binding to integrins (Aricescu and Jones, 2007). ICAM-1 is secreted by vascular endothelial cells in HIE. Levels are significantly elevated on days 3–7 post-insult in human neonates with HIE, and increasing levels correlate with worse prognosis (Huseynova et al., 2012; Huseynova et al., 2014). ICAM-1 expression is also increased after exposure to various inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, TNFα, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and endotoxin (Lv et al., 2015). VCAM-1 is also elevated in the first week following HIE in human neonates, versus elevations within the first 48 hours in the rat model of neonatal HIE (Huseynova et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015).

VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 both act as ligands for the β-1 integrin very late activating-antigen-4 (VLA-4) and the β-2 integrin leukocyte function antigen-1 (LFA-1) expressed by MSCs and HSCs. Their roles have been elucidated in studies showing that antibodies to VCAM-1 and VLA-4 can prevent stem cell homing (Papayannopoulou and Craddock, 1997; Vermeulen et al., 1998). MSCs have been demonstrated to adhere to endothelial cells via binding and rolling mediated through P-selectin followed by VLA-4/VCAM-1 dependent trans-endothelial migration. Adhesion of MSCs to endothelial cells is significantly diminished when a VLA-4 or VCAM-1 inhibitor is used (Ruster et al., 2006; Steingen et al., 2008).

MMPs

In addition to MMP-9’s role in stem cell mobilization, it also functions in stem cell adhesion. MMPs degrade the extracellular matrix and allow stem cells to migrate through basement membrane barriers. When secretion of MMP-9 and MMP-2 is induced by SDF-1 and other growth factors, HSCs migration through basement membrane barriers along the SDF-1 gradient is enhanced (Marquez-Curtis et al., 2011). Membrane type 1 MMP (MT1-MMP) is expressed by bone marrow mononuclear cells and circulating human CD34+ stem cells and can be activated by SDF-1 and G-CSF (Janowska-Wieczorek et al., 2000; Vagima et al., 2009). MT1-MMP has been demonstrated to be important in both SDF-1-induced and SCF/c-kit-induced migration, mobilization, and homing of stem cells (Avigdor et al., 2004; Shirvaikar et al., 2004; Vagima et al., 2009).

Stem Cell Proliferation

As circulating stem cells appears to act, at least in part, through paracrine mechanisms rather than adhesion and direct tissue integration, it is important to also discuss stem cell paracrine effects such as the effects on endogenous cell proliferation. There exists a complex interaction between circulating stem cells and the neural stem cell niche, however, that is beyond the scope of this current review. For more information on the factors involved in altering stem cell survival and differentiation, we would direct the reader to previously published manuscripts which fully review those topics (Decimo et al., 2012; Ruddy and Morshead, 2018).

IL-6

IL-6 is another pro-inflammatory mediator that at high levels can also cause inflammation, enhance vascular permeability, and increase secondary cerebral edema (Lv et al., 2015). IL-6 is released from microglia, astrocytes, and neurons (Saliba and Henrot, 2001) in response to brain injury, and levels are significantly higher in the cord blood and CSF of neonates with HIE, with increasing plasma IL-6 levels associated with increasing HIE severity (Chiesa et al., 2003; Aly et al., 2006; Orrock et al., 2016). Serum samples of IL-6 were elevated at 24 and 72 hours in infants with HIE and were correlated with adverse outcome (Orrock et al., 2016). IL-6 levels are also elevated in human neonates with HIE in serum and CSF samples drawn within 24 hours of birth., and increased CSF IL-6 levels correlated with worse neurologic outcomes at 6 months of age and increased mortality rate (Aly et al., 2006).

Like many other pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 also functions paradoxically as a neuroprotective mediator by inhibiting the production of TNFα and IL-1β and through increasing neural growth factor release (Lv et al., 2015) and promoting proliferation of neural stem progenitor cells (Covey et al., 2011; Pimentel-Coelho et al., 2012). In a neonatal rat model of HI-injury, addition of IL-6 enhanced neuronal growth and self-renewal NPCs, and NPC numbers were reduced with addition of IL-6 inhibitor (Covey et al., 2011).

VEGF

In addition to VEGF’s role in stem cell migration, it also induces stem cell proliferation. VEGF functions to protect the cerebral cortex from hypoxic injury and promote survival, repair, and regeneration of neurons in the cerebral cortex when hypoxic injury does occur. VEGF also causes proliferation and angiogenesis of vascular endothelial cells and enhances the proliferation of NPCs (Jin et al., 2002b; Sun et al., 2010; Dzietko et al., 2013). Intracerebral injection of VEGF led to increased endothelial proliferation, increase in total vessel volume, and reduced brain injury following neonatal ischemic stroke in a neonatal rat model (Dzietko et al., 2013). In a similar animal model, rats transplanted with VEGF-transfected NPCs post HI-injury had improved learning and memory abilities at 30 days (Yao et al., 2016).

Conclusion

Stem cell transplant has shown promise as a therapy for neonatal HIE, but further research is needed to prove its safety and efficacy. One of the ways that efficacy of stem cell transplantation may be improved in the future is through the alteration of the stem cells and upregulation of certain factors to optimize migration, adhesion, and differentiation. It will be important for future investigations of MSC manipulation to assess not only the effects on the injured tissue, but also the effects on the upregulated factors on healthy tissue (trapping of cells in the microcirculation of the lung, effects on the immune system, etc.). By examining the factors that are naturally elevated after neonatal HI brain injury, we hope to better understand the interactions between the injured tissue and the endogenous stem cells. Understanding the interactions of these biomarkers with stem cells opens the door to future research into manipulating these biomarkers to advance the success of stem cell treatments in neonates with HIE.

Additional file (4.1KB, pdf) : Open peer review report 1.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: We have no financial ties to any products described in the study and have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Copyright license agreement: The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Financial support: None.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Open peer reviewer: Yuan Wang, Sichuan University, China.

References

- 1.Adhami F, Yu D, Yin W, Schloemer A, Burns KA, Liao G, Degen JL, Chen J, Kuan CY. Deleterious effects of plasminogen activators in neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1704–1716. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez JI, Katayama T, Prat A. Glial influence on the blood brain barrier. Glia. 2013;61:1939–1958. doi: 10.1002/glia.22575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aly H, Khashaba MT, El-Ayouty M, El-Sayed O, Hasanein BM. IL-1beta, IL-6 and TNF-alpha and outcomes of neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Brain Dev. 2006;28:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aly H, Hassanein S, Nada A, Mohamed MH, Atef SH, Atiea W. Vascular endothelial growth factor in neonates with perinatal asphyxia. Brain Dev. 2009;31:600–604. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aricescu AR, Jones EY. Immunoglobulin superfamily cell adhesion molecules: zippers and signals. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avigdor A, Schwartz S, Goichberg P, Petit I, Hardan I, Resnick I, Slavin S, Nagler A, Lapidot T. Membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase is directly involved in G-CSF induced human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell mobilization. Blood. 2004;104:2675–2675. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballen K. Umbilical cord blood transplantation: challenges and future directions. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:1312–1315. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bednarek N, Svedin P, Garnotel R, Favrais G, Loron G, Schwendiman L, Hagberg H, Morville P, Mallard C, Gressens P. Increased MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in mouse neonatal brain and plasma and in human neonatal plasma after hypoxia-ischemia: a potential marker of neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatr Res. 2012;71:63–70. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belmadani A, Tran PB, Ren D, Miller RJ. Chemokines regulate the migration of neural progenitors to sites of neuroinflammation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3182–3191. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0156-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benraiss A, Chmielnicki E, Lerner K, Roh D, Goldman SA. Adenoviral brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces both neostriatal and olfactory neuronal recruitment from endogenous progenitor cells in the adult forebrain. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6718–6731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06718.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardino L, Agasse F, Silva B, Ferreira R, Grade S, Malva JO. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulates survival, proliferation, and neuronal differentiation in neonatal subventricular zone cell cultures. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2361–2371. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blais V, Rivest S. Effects of TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma on nitric oxide-induced neurotoxicity in the mouse brain. J Immunol. 2004;172:7043–7052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borghesani PR, Peyrin JM, Klein R, Rubin J, Carter AR, Schwartz PM, Luster A, Corfas G, Segal RA. BDNF stimulates migration of cerebellar granule cells. Development. 2002;129:1435–1442. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cashen AF, Nervi B, DiPersio J. AMD3100: CXCR4 antagonist and rapid stem cell-mobilizing agent. Future Oncol. 2007;3:19–27. doi: 10.2217/14796694.3.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, Tepper OM, Bastidas N, Kleinman ME, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10:858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H, Xiong T, Qu Y, Zhao F, Ferriero D, Mu D. mTOR activates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and inhibits neuronal apoptosis in the developing rat brain during the early phase after hypoxia-ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2012;507:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S, Li J, Peng H, Zhou J, Fang H. Administration of erythropoietin exerts protective effects against glucocorticoid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head in rats. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:840–848. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Y, Gidday JM, Yan Q, Shah AR, Holtzman DM. Marked age-dependent neuroprotection by brain-derived neurotrophic factor against neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:521–529. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiesa C, Pellegrini G, Panero A, De Luca T, Assumma M, Signore F, Pacifico L. Umbilical cord interleukin-6 levels are elevated in term neonates with perinatal asphyxia. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:352–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chmielnicki E, Benraiss A, Economides AN, Goldman SA. Adenovirally expressed noggin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor cooperate to induce new medium spiny neurons from resident progenitor cells in the adult striatal ventricular zone. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2133–2142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1554-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotten CM, Murtha AP, Goldberg RN, Grotegut CA, Smith PB, Goldstein RF, Fisher KA, Gustafson KE, Waters-Pick B, Swamy GK, Rattray B, Tan S, Kurtzberg J. Feasibility of autologous cord blood cells for infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2014;164:973–979.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Covey MV, Loporchio D, Buono KD, Levison SW. Opposite effect of inflammation on subventricular zone versus hippocampal precursors in brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:616–626. doi: 10.1002/ana.22473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cowell RM, Xu H, Galasso JM, Silverstein FS. Hypoxic-ischemic injury induces macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha expression in immature rat brain. Stroke. 2002;33:795–801. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.103740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui LL, Nitzsche F, Pryazhnikov E, Tibeykina M, Tolppanen L, Rytkönen J, Huhtala T, Mu JW, Khiroug L, Boltze J, Jolkkonen J. Integrin α4 overexpression on rat mesenchymal stem cells enhances transmigration and reduces cerebral embolism after intracarotid injection. Stroke. 2017;48:2895–2900. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunningham LA, Wetzel M, Rosenberg GA. Multiple roles for MMPs and TIMPs in cerebral ischemia. Glia. 2005;50:329–339. doi: 10.1002/glia.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Decimo I, Bifari F, Krampera M, Fumagalli G. Neural stem cell niches in health and diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:1755–1783. doi: 10.2174/138161212799859611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng J, Zou ZM, Zhou TL, Su YP, Ai GP, Wang JP, Xu H, Dong SW. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can be mobilized into peripheral blood by G-CSF in vivo and integrate into traumatically injured cerebral tissue. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:641–651. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:313–326. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas-Escobar M, Weiss MD. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a review for the clinician. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:397–403. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglas-Escobar M, Rossignol C, Steindler D, Zheng T, Weiss MD. Neurotrophin-induced migration and neuronal differentiation of multipotent astrocytic stem cells in vitro. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dziegielewska KM, Moller JE, Potter AM, Ek J, Lane MA, Saunders NR. Acute-phase cytokines IL-1beta and TNF-alpha in brain development. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;299:335–345. doi: 10.1007/s004419900157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dzietko M, Derugin N, Wendland MF, Vexler ZS, Ferriero DM. Delayed VEGF treatment enhances angiogenesis and recovery after neonatal focal rodent stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:189–200. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0221-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elmahdy H, El-Mashad AR, El-Bahrawy H, El-Gohary T, El-Barbary A, Aly H. Human recombinant erythropoietin in asphyxia neonatorum: pilot trial. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1135–1142. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ergenekon E, Gucuyener K, Erbas D, Aral S, Koc E, Atalay Y. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum vascular endothelial growth factor and nitric oxide levels in newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Brain Dev. 2004;26:283–286. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(03)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erslev A. Humoral regulation of red cell production. Blood. 1953;8:349–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fabel K, Fabel K, Tam B, Kaufer D, Baiker A, Simmons N, Kuo CJ, Palmer TD. VEGF is necessary for exercise-induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2803–2812. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu X, Han B, Cai S, Lei Y, Sun T, Sheng Z. Migration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and its possible role in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:185–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasche Y, Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Copin JC, Kawase M, Massengale J, Chan PH. Early appearance of activated matrix metalloproteinase-9 after focal cerebral ischemia in mice: a possible role in blood-brain barrier dysfunction. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1020–1028. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199909000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong Y, Fan Y, Hoover-Plow J Plasminogen regulates stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4-mediated hematopoietic stem cell mobilization by activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2035–2043. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.229583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo CJ, Douglas SD, Gao Z, Wolf BA, Grinspan J, Lai JP, Riedel E, Ho WZ. Interleukin-1beta upregulates functional expression of neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R) via NF-kappaB in astrocytes. Glia. 2004;48:259–266. doi: 10.1002/glia.20079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han BH, Holtzman DM. BDNF protects the neonatal brain from hypoxic-ischemic injury in vivo via the ERK pathway. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5775–5781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05775.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Havell EA. Production of tumor necrosis factor during murine listeriosis. J Immunol. 1987;139:4225–4231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heeschen C, Aicher A, Lehmann R, Fichtlscherer S, Vasa M, Urbich C, Mildner-Rihm C, Martin H, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Erythropoietin is a potent physiologic stimulus for endothelial progenitor cell mobilization. Blood. 2003;102:1340–1346. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heissig B, Hattori K, Dias S, Friedrich M, Ferris B, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Besmer P, Lyden D, Moore MA, Werb Z, Rafii S. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell. 2002;109:625–637. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00754-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heissig B, Lund LR, Akiyama H, Ohki M, Morita Y, Romer J, Nakauchi H, Okumura K, Ogawa H, Werb Z, Dano K, Hattori K. The plasminogen fibrinolytic pathway is required for hematopoietic regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:658–670. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hohn A, Leibrock J, Bailey K, Barde YA. Identification and characterization of a novel member of the nerve growth factor/brain-derived neurotrophic factor family. Nature. 1990;344:339–341. doi: 10.1038/344339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang YF, Zhuang SQ, Chen DP, Liang YJ, Li XY. Angiogenesis and its regulatory factors in brain tissue of neonatal rat hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2004;42:210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huseynova S, Panakhova N, Orujova P. Endothelial dysfunction and cellular adhesion molecule activation in preterm infants with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Am Int J Contemp Res. 2012;2:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huseynova S, Panakhova N, Orujova P, Hasanov S, Guliyev M, Orujov A. Elevated levels of serum sICAM-1 in asphyxiated low birth weight newborns. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6850. doi: 10.1038/srep06850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ida JA, Jr, Dubois-Dalcq M, McKinnon RD. Expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase c-kit in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. J Neurosci Res. 1993;36:596–606. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490360512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Imam SS, Gad GI, Atef SH, Shawky MA. Cord blood brain derived neurotrophic factor: diagnostic and prognostic marker in fullterm newborns with perinatal asphyxia. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009;12:1498–1504. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2009.1498.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ip JE, Wu Y, Huang J, Zhang L, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Mesenchymal stem cells use integrin beta1 not CXC chemokine receptor 4 for myocardial migration and engraftment. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2873–2882. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ivacko J, Szaflarski J, Malinak C, Flory C, Warren JS, Silverstein FS. Hypoxic-ischemic injury induces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in neonatal rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:759–770. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199707000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Janowska-Wieczorek A, Matsuzaki A, L AM. The hematopoietic microenvironment: matrix metalloproteinases in the hematopoietic microenvironment. Hematology. 2000;4:515–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang L, Newman M, Saporta S, Chen N, Sanberg C, Sanberg PR, Willing AE. MIP-1alpha and MCP-1 induce migration of human umbilical cord blood cells in models of stroke. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2008;5:118–124. doi: 10.2174/156720208784310259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jimenez J, Lesage F, Richter J, Nagatomo T, Salaets T, Zia S, Mori Da Cunha MG, Vanoirbeek J, Deprest JA, Toelen J. Upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in amniotic fluid stem cells enhances their potential to attenuate lung injury in a preterm rabbit model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Neonatology. 2018;113:275–285. doi: 10.1159/000481794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jin K, Mao XO, Greenberg DA. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates neurite outgrowth from cerebral cortical neurons via Rho kinase signaling. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:236–242. doi: 10.1002/neu.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jin K, Mao XO, Sun Y, Xie L, Greenberg DA. Stem cell factor stimulates neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2002a;110:311–319. doi: 10.1172/JCI15251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jin K, Zhu Y, Sun Y, Mao XO, Xie L, Greenberg DA. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulates neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002b;99:11946–11950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182296499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Junge CE, Sugawara T, Mannaioni G, Alagarsamy S, Conn PJ, Brat DJ, Chan PH, Traynelis SF. The contribution of protease-activated receptor 1 to neuronal damage caused by transient focal cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13019–13024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235594100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Juul SE, Stallings SA, Christensen RD. Erythropoietin in the cerebrospinal fluid of neonates who sustained CNS injury. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:543–547. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199911000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawahara N, Croll SD, Wiegand SJ, Klatzo I. Cortical spreading depression induces long-term alterations of BDNF levels in cortex and hippocampus distinct from lesion effects: implications for ischemic tolerance. Neurosci Res. 1997;29:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khaibullina AA, Rosenstein JM, Krum JM. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes neurite maturation in primary CNS neuronal cultures. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;148:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khairallah MI, Kassem LA, Yassin NA, Gamal el Din MA, Zekri M, Attia M. Activation of migration of endogenous stem cells by erythropoietin as potential rescue for neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2016;121:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klein R, Smeyne RJ, Wurst W, Long LK, Auerbach BA, Joyner AL, Barbacid M. Targeted disruption of the trkB neurotrophin receptor gene results in nervous system lesions and neonatal death. Cell. 1993;75:113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koch AE, Kunkel SL, Harlow LA, Mazarakis DD, Haines GK, Burdick MD, Pope RM, Strieter RM. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha. A novel chemotactic cytokine for macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:921–928. doi: 10.1172/JCI117097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kolev K, Skopal J, Simon L, Csonka E, Machovich R, Nagy Z. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in post-hypoxic human brain capillary endothelial cells: H2O2 as a trigger and NF-kappaB as a signal transducer. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:528–537. doi: 10.1160/TH03-02-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krueger JM, Fang J, Taishi P, Chen Z, Kushikata T, Gardi J. Sleep. A physiologic role for IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:148–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar S, Ponnazhagan S. Mobilization of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in vivo augments bone healing in a mouse model of segmental bone defect. Bone. 2012;50:1012–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lau LT, Yu AC. Astrocytes produce and release interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon-gamma following traumatic and metabolic injury. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:351–359. doi: 10.1089/08977150151071035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li J, Guo W, Xiong M, Zhang S, Han H, Chen J, Mao D, Yu H, Zeng Y. Erythropoietin facilitates the recruitment of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to sites of spinal cord injury. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13:1806–1812. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li L, McBride DW, Doycheva D, Dixon BJ, Krafft PR, Zhang JH, Tang J. G-CSF attenuates neuroinflammation and stabilizes the blood-brain barrier via the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3beta signaling pathway following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in rats. Exp Neurol. 2015;272:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu J, Feng ZC. Increased umbilical cord plasma interleukin-1 beta levels was correlated with adverse outcomes of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:178–182. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu NM, Tian J, Wang WW, Han GF, Cheng J, Huang J, Zhang JY. Effect of erythropoietin on mesenchymal stem cell differentiation and secretion in vitro in an acute kidney injury microenvironment. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:6477–6487. doi: 10.4238/2013.February.28.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lv H, Wang Q, Wu S, Yang L, Ren P, Yang Y, Gao J, Li L. Neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy-related biomarkers in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;450:282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma L, Li XW, Zhang SJ, Yang F, Zhu GM, Yuan XB, Jiang W. Interleukin-1 beta guides the migration of cortical neurons. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:114. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Malamitsi-Puchner A, Economou E, Rigopoulou O, Boutsikou T. Perinatal changes of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in pre- and fullterm neonates. Early Hum Dev. 2004;76:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Manova K, Bachvarova RF, Huang EJ, Sanchez S, Pronovost SM, Velazquez E, McGuire B, Besmer P. c-kit receptor and ligand expression in postnatal development of the mouse cerebellum suggests a function for c-kit in inhibitory interneurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4663–4676. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04663.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marquez-Curtis LA, Turner AR, Sridharan S, Ratajczak MZ, Janowska-Wieczorek A The ins and outs of hematopoietic stem cells: studies to improve transplantation outcomes. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7:590–607. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marti HH, Wenger RH, Rivas LA, Straumann U, Digicaylioglu M, Henn V, Yonekawa Y, Bauer C, Gassmann M. Erythropoietin gene expression in human, monkey and murine brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:666–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsui Y, Zsebo KM, Hogan BL. Embryonic expression of a haematopoietic growth factor encoded by the Sl locus and the ligand for c-kit. Nature. 1990;347:667–669. doi: 10.1038/347667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matthys P, Hatse S, Vermeire K, Wuyts A, Bridger G, Henson GW, De Clercq E, Billiau A, Schols D. AMD3100, a potent and specific antagonist of the stromal cell-derived factor-1 chemokine receptor CXCR4, inhibits autoimmune joint inflammation in IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:4686–4692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Millauer B, Wizigmann-Voos S, Schnurch H, Martinez R, Moller NP, Risau W, Ullrich A. High affinity VEGF binding and developmental expression suggest Flk-1 as a major regulator of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Cell. 1993;72:835–846. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miller JT, Bartley JH, Wimborne HJ, Walker AL, Hess DC, Hill WD, Carroll JE. The neuroblast and angioblast chemotaxic factor SDF-1 (CXCL12) expression is briefly up regulated by reactive astrocytes in brain following neonatal hypoxic-ischemic injury. BMC Neurosci. 2005;6:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mori M, Matsubara K, Matsubara Y, Uchikura Y, Hashimoto H, Fujioka T, Matsumoto T. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha plays a crucial role based on neuroprotective role in neonatal brain injury in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:18018–18032. doi: 10.3390/ijms160818018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Motro B, van der Kooy D, Rossant J, Reith A, Bernstein A. Contiguous patterns of c-kit and steel expression: analysis of mutations at the W and Sl loci. Development (Cambridge, England) 1991;113:1207–1221. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.No authors listed (2018) IL1B interleukin 1 beta [Homo sapiens (human)] Bethesda (MD, USA): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; [Google Scholar]

- 89.Old LJ. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) Science. 1985;230:630–632. doi: 10.1126/science.2413547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oranskii IE, Rudakov AA, Mironova IB. Comparative study of the action exerted by sodium chloride iodine-bromine baths, corrected in their composition, on various hemodynamic and hemostasic characteristics in ischemic heart disease. Vopr Kurortol Fizioter Lech Fiz Kult. 1977:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Orrock JE, Panchapakesan K, Vezina G, Chang T, Harris K, Wang Y, Knoblach S, Massaro AN. Association of brain injury and neonatal cytokine response during therapeutic hypothermia in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:742–747. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Orzylowska O, Oderfeld-Nowak B, Zaremba M, Januszewski S, Mossakowski M. Prolonged and concomitant induction of astroglial immunoreactivity of interleukin-1beta and interleukin-6 in the rat hippocampus after transient global ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 1999;263:72–76. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Oygur N, Sonmez O, Saka O, Yegin O. Predictive value of plasma and cerebrospinal fluid tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 beta concentrations on outcome of full term infants with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;79:F190–193. doi: 10.1136/fn.79.3.f190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Papayannopoulou T, Craddock C. Homing and trafficking of hemopoietic progenitor cells. Acta Haematologica. 1997;97:97–104. doi: 10.1159/000203665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Parikh P, Juul SE. Neuroprotective strategies in neonatal brain injury. J Pediatr. 2018;192:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Peled A, Grabovsky V, Habler L, Sandbank J, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Petit I, Ben-Hur H, Lapidot T, Alon R. The chemokine SDF-1 stimulates integrin-mediated arrest of CD34(+) cells on vascular endothelium under shear flow. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1199–1211. doi: 10.1172/JCI7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, Lahav M, Peled A, Habler L, Ponomaryov T, Taichman RS, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Fujii N, Sandbank J, Zipori D, Lapidot T. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pimentel-Coelho PM, Rosado-de-Castro PH, da Fonseca LM, Mendez-Otero R. Umbilical cord blood mononuclear cell transplantation for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Res. 2012;71:464–473. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Plumier JC, David JC, Robertson HA, Currie RW. Cortical application of potassium chloride induces the low-molecular weight heat shock protein (Hsp27) in astrocytes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:781–790. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Prass K, Scharff A, Ruscher K, Lowl D, Muselmann C, Victorov I, Kapinya K, Dirnagl U, Meisel A. Hypoxia-induced stroke tolerance in the mouse is mediated by erythropoietin. Stroke. 2003;34:1981–1986. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000080381.76409.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pruijt JF, Fibbe WE, Laterveer L, Pieters RA, Lindley IJ, Paemen L, Masure S, Willemze R, Opdenakker G. Prevention of interleukin-8-induced mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in rhesus monkeys by inhibitory antibodies against the metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10863–10868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Qiu FH, Ray P, Brown K, Barker PE, Jhanwar S, Ruddle FH, Besmer P. Primary structure of c-kit: relationship with the CSF-1/PDGF receptor kinase family--oncogenic activation of v-kit involves deletion of extracellular domain and C terminus. EMBO J. 1988;7:1003–1011. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ramirez-Rodriguez GB, Perera-Murcia GR, Ortiz-Lopez L, Vega-Rivera NM, Babu H, Garcia-Anaya M, Gonzalez-Olvera JJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor influences migration and focal adhesions, but not proliferation or viability, of human neural stem/progenitor cells derived from olfactory epithelium. Neurochem Int. 2017;108:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rennert RC, Sorkin M, Garg RK, Gurtner GC. Stem cell recruitment after injury: lessons for regenerative medicine. Regen Med. 2012;7:833–850. doi: 10.2217/rme.12.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ribatti D, Presta M, Vacca A, Ria R, Giuliani R, Dell’Era P, Nico B, Roncali L, Dammacco F. Human erythropoietin induces a pro-angiogenic phenotype in cultured endothelial cells and stimulates neovascularization in vivo. Blood. 1999;93:2627–2636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rosell A, Ortega-Aznar A, Alvarez-Sabin J, Fernandez-Cadenas I, Ribo M, Molina CA, Lo EH, Montaner J. Increased brain expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 after ischemic and hemorrhagic human stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:1399–1406. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000223001.06264.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rosenkranz K, Kumbruch S, Lebermann K, Marschner K, Jensen A, Dermietzel R, Meier C. The chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12 contributes to the ‘homing’ of umbilical cord blood cells to a hypoxic-ischemic lesion in the rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:1223–1233. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ruddy RM, Morshead CM. Home sweet home: the neural stem cell niche throughout development and after injury. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;371:125–141. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2658-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ruster B, Gottig S, Ludwig RJ, Bistrian R, Muller S, Seifried E, Gille J, Henschler R. Mesenchymal stem cells display coordinated rolling and adhesion behavior on endothelial cells. Blood. 2006;108:3938–3944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Saliba E, Henrot A. Inflammatory mediators and neonatal brain damage. Biology of the neonate. 2001;79:224–227. doi: 10.1159/000047096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schmidt NO, Przylecki W, Yang W, Ziu M, Teng Y, Kim SU, Black PM, Aboody KS, Carroll RS. Brain tumor tropism of transplanted human neural stem cells is induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. Neoplasia. 2005;7:623–629. doi: 10.1593/neo.04781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Serfozo P, Schlarman MS, Pierret C, Maria BL, Kirk MD. Selective migration of neuralized embryonic stem cells to stem cell factor and media conditioned by glioma cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2006;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shirvaikar N, Montano J, Turner AR, Ratajczak MZ, Janowska-Wieczorek A. Upregulation of MT1-MMP expression by hyaluronic acid enhances homing-related responses of hematopoietic CD34+ cells to an SDF-1 gradient. Blood. 2004;104:2889. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Silveira RC, Procianoy RS. Interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of term newborn infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2003;143:625–629. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Silverstein FS, Barks JD, Hagan P, Liu XH, Ivacko J, Szaflarski J. Cytokines and perinatal brain injury. Neurochem Int. 1997;30:375–383. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(96)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Steingen C, Brenig F, Baumgartner L, Schmidt J, Schmidt A, Bloch W. Characterization of key mechanisms in transmigration and invasion of mesenchymal stem cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:1072–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sullivan CB, Porter RM, Evans CH, Ritter T, Shaw G, Barry F, Murphy JM. TNFalpha and IL-1beta influence the differentiation and migration of murine MSCs independently of the NF-kappaB pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5:104. doi: 10.1186/scrt492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sun J, Zhou W, Ma D, Yang Y. Endothelial cells promote neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation associated with VEGF activated Notch and Pten signaling. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:2345–2353. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sun L, Lee J, Fine HA. Neuronally expressed stem cell factor induces neural stem cell migration to areas of brain injury. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1364–1374. doi: 10.1172/JCI20001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sun Y, Jin K, Xie L, Childs J, Mao XO, Logvinova A, Greenberg DA. VEGF-induced neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1843–1851. doi: 10.1172/JCI17977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sunagawa S, Ichiyama T, Honda R, Fukunaga S, Maeba S, Furukawa S. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in perinatal asphyxia. Brain Dev. 2009;31:588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Szaflarski J, Burtrum D, Silverstein FS. Cerebral hypoxia-ischemia stimulates cytokine gene expression in perinatal rats. Stroke. 1995;26:1093–1100. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Taub DD, Conlon K, Lloyd AR, Oppenheim JJ, Kelvin DJ. Preferential migration of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to MIP-1 alpha and MIP-1 beta. Science. 1993;260:355–358. doi: 10.1126/science.7682337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Teixeira M, Rodrigues-Santos P, Garrido P, Costa E, Parada B, Sereno J, Alves R, Belo L, Teixeira F, Santos-Silva A, Reis F. Cardiac antiapoptotic and proproliferative effect of recombinant human erythropoietin in a moderate stage of chronic renal failure in the rat. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2012;4:76–83. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.92743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Turrin NP, Rivest S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha but not interleukin 1 beta mediates neuroprotection in response to acute nitric oxide excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:143–151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4032-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Vagima Y, Avigdor A, Goichberg P, Shivtiel S, Tesio M, Kalinkovich A, Golan K, Dar A, Kollet O, Petit I, Perl O, Rosenthal E, Resnick I, Hardan I, Gellman YN, Naor D, Nagler A, Lapidot T. MT1-MMP and RECK are involved in human CD34+ progenitor cell retention, egress, and mobilization. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:492–503. doi: 10.1172/JCI36541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Van Coillie E, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. The MCP/eotaxin subfamily of CC chemokines. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;10:61–86. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Van Lint P, Libert C. Chemokine and cytokine processing by matrix metalloproteinases and its effect on leukocyte migration and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:1375–1381. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vasiljevic B, Maglajlic-Djukic S, Gojnic M, Stankovic S, Ignjatovic S, Lutovac D. New insights into the pathogenesis of perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Pediatr Int. 2011;53:454–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Vermeulen M, Le Pesteur F, Gagnerault MC, Mary JY, Sainteny F, Lepault F. Role of adhesion molecules in the homing and mobilization of murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 1998;92:894–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang H, Wang X, Qu J, Yue Q, Hu Y, Zhang H. VEGF enhances the migration of MSCs in neural differentiation by regulating focal adhesion turnover. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:2728–2742. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wang K, Li Y, Zhu T, Zhang Y, Li W, Lin W, Li J, Zhu C. Overexpression of c-Met in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improves their effectiveness in homing and repair of acute liver failure. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:162. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0614-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang X, Jung J, Asahi M, Chwang W, Russo L, Moskowitz MA, Dixon CE, Fini ME, Lo EH. Effects of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out on morphological and motor outcomes after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7037–7042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-07037.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wang Y, Deng Y, Zhou GQ. SDF-1alpha/CXCR4-mediated migration of systemically transplanted bone marrow stromal cells towards ischemic brain lesion in a rat model. Brain Res. 2008;1195:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wride MA, Sanders EJ. Potential roles for tumour necrosis factor alpha during embryonic development. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1995;191:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00215292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wu YW, Mathur AM, Chang T, McKinstry RC, Mulkey SB, Mayock DE, Van Meurs KP, Rogers EE, Gonzalez FF, Comstock BA, Juul SE, Msall ME, Bonifacio SL, Glass HC, Massaro AN, Dong L, Tan KW, Heagerty PJ, Ballard RA. High-dose erythropoietin and hypothermia for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a phase II trial. Pediatrics 137. 2016 doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xiang Q, Hong D, Liao Y, Cao Y, Liu M, Pang J, Zhou J, Wang G, Yang R, Wang M, Xiang AP. Overexpression of gremlin1 in mesenchymal stem cells improves hindlimb ischemia in mice by enhancing cell survival. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232:996–1007. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Xiao Q, Wang SK, Tian H, Xin L, Zou ZG, Hu YL, Chang CM, Wang XY, Yin QS, Zhang XH, Wang LY. TNF-alpha increases bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell migration to ischemic tissues. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2012;62:409–414. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9317-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Xiong M, Chen S, Yu H, Liu Z, Zeng Y, Li F. Neuroprotection of erythropoietin and methylprednisolone against spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2011;31:652–656. doi: 10.1007/s11596-011-0576-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yang Y, Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinases as therapeutic targets for stroke. Brain Res. 2015;1623:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Yao Y, Zheng XR, Zhang SS, Wang X, Yu XH, Tan JL, Yang YJ. Transplantation of vascular endothelial growth factor-modified neural stem/progenitor cells promotes the recovery of neurological function following hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:1456–1463. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.191220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yu Q, Liu L, Lin J, Wang Y, Xuan X, Guo Y, Hu S. SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis mediates the migration of mesenchymal stem cells to the hypoxic-ischemic brain lesion in a rat model. Cell J. 2015;16:440–447. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2015.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zgheib C, Xu J, Mallette AC, Caskey RC, Zhang L, Hu J, Liechty KW. SCF increases in utero-labeled stem cells migration and improves wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23:583–590. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhang SC, Fedoroff S. Cellular localization of stem cell factor and c-kit receptor in the mouse nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhang SC, Fedoroff S. Expression of stem cell factor and c-kit receptor in neural cells after brain injury. Acta Neuropathol. 1999;97:393–398. doi: 10.1007/s004010051003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhao BQ, Wang S, Kim HY, Storrie H, Rosen BR, Mooney DJ, Wang X, Lo EH. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in delayed cortical responses after stroke. Nat Med. 2006;12:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nm1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Zhu C, Kang W, Xu F, Cheng X, Zhang Z, Jia L, Ji L, Guo X, Xiong H, Simbruner G, Blomgren K, Wang X. Erythropoietin improved neurologic outcomes in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e218–226. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zwezdaryk KJ, Coffelt SB, Figueroa YG, Liu J, Phinney DG, LaMarca HL, Florez L, Morris CB, Hoyle GW, Scandurro AB. Erythropoietin a hypoxia-regulated factor, elicits a pro-angiogenic program in human mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:640–652. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.