Abstract

To date, several genome editing technologies have been developed and are widely utilized in many fields of biology. Most of these technologies, if not all, use nucleases to create DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), raising the potential risk of cell death and/or oncogenic transformation. The risks hinder their therapeutic applications in humans. Here, we show that in vivo targeted single-nucleotide editing in zebrafish, a vertebrate model organism, can be successfully accomplished with the Target-AID system, which involves deamination of a targeted cytidine to create a nucleotide substitution from cytosine to thymine after replication. Application of the system to two zebrafish genes, chordin (chd) and one-eyed pinhead (oep), successfully introduced premature stop codons (TAG or TAA) in the targeted genomic loci. The modifications were heritable and faithfully produced phenocopies of well-known homozygous mutants of each gene. These results demonstrate for the first time that the Target-AID system can create heritable nucleotide substitutions in vivo in a programmable manner, in vertebrates, namely zebrafish.

Introduction

Genome editing technologies such as ZFN1, TALEN2 and the CRISPR/Cas9 system3 have become powerful tools for studying gene functions in model organisms, with a potential for gene therapy in humans4. Experimentally, therapeutic genome editing has been achieved in recent studies using technologies that involve non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-mediated gene disruption5–8, NHEJ-mediated gene correction9, homology directed repair (HDR)-mediated gene correction10–12, and HDR-mediated gene addition13. These genome editing technologies have enormous potential for gene therapy. It should be kept in mind, however, that all of these technologies use nucleases to create DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), and thus carry the risk of cell death and/or oncogenic transformation14,15. Therefore, DSB-free genome editing methods should be developed for therapeutic genome editing in humans.

We have recently created a novel single-nucleotide-editing technology that utilizes the CRISPR/Cas9 system for targeting without DSBs16. This technology is called the “Target-AID system”. In this system, a fusion protein consisting of nuclease-dead Cas9 (dCas9) or Cas9 nickase (nCas9(D10A))3, and the activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)17 derived from sea lamprey, PmCDA1, is introduced in cells with a single guide RNA (sgRNA). The sgRNA recruits the fusion protein, dCas9-PmCDA1, to target sites. AID tethered to dCas9 or nCas9(D10A) can deaminate cytosine in DNA within a five nucleotide window, resulting in the conversion of cytosine to thymine (C > T) after replication. The Target-AID system has been used to generate targeted C > T transitions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian cultured cells16, but not yet in any vertebrates in vivo. This system has the potential to allow DSB-free genome editing in vertebrates, including humans, and might provide an alternative approach for gene therapy through single-nucleotide substitutions without DSBs.

Here we describe in vivo targeted single-nucleotide editing in zebrafish with the Target-AID system. The chordin (chd) and one-eyed pinhead (oep) genes were selected as target genes because the phenotypes induced by the loss (−/−) of each gene are well known. We first showed that the Target-AID system using dCas9-PmCDA1 or nCas9(D10A)-PmCDA1 induced targeted C > T substitutions in zebrafish embryos. Genomic analyses of F1 embryos produced by the founder fish (G0 fish), which had been co-injected with the dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA and sgRNA, revealed that the targeted cytosines were substituted by thymines at appreciable frequencies. In addition, F2 fish with homozygous nucleotide substitutions in the target genes (chd or oep) manifested well-known mutant phenotypes. These results demonstrate for the first time that the Target-AID system produces programmable nucleotide substitutions in vertebrates in vivo.

Results

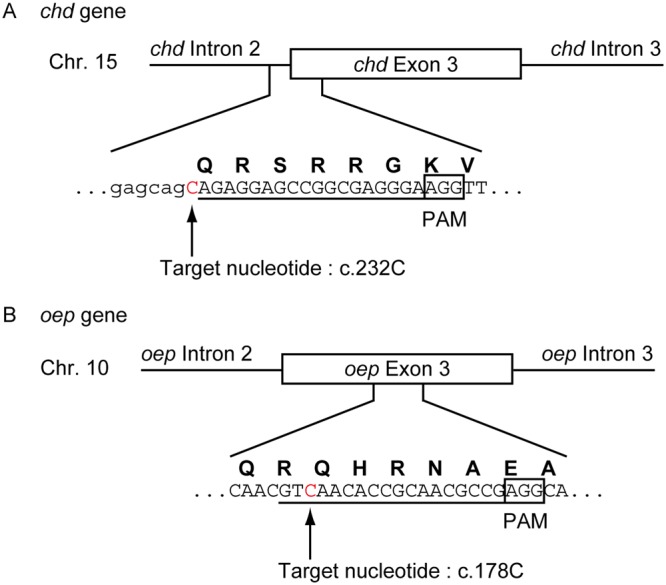

A strategy for in vivo nucleotide substitutions in zebrafish via the Target-AID system

In order to evaluate the feasibility of the Target-AID system in zebrafish, we first constructed a pCS2-based expression vector for in vitro synthesis of dCas9-NLS-FLAG-PmCDA1 mRNA (dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA) and nCas9(D10A)-NLS-FLAG-PmCDA1 mRNA (nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA). As targets of the Target-AID system, we selected two genes, the chd gene and the oep gene, because the phenotypes arising from the loss of each gene (−/−) have been thoroughly described. From our experiences with the CRISPR/Cas9 system, we were aware that single guide RNAs with 18 nucleotides targeting sequences work well18, and from the previous report for the Target-AID system, that cytosines between the -20 to -16 positions from the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (5′–NGG for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9))3 are efficiently deaminated16. We therefore searched for cytosines in the chd and oep genes that were located -20 to -16 positions from potential PAM sequences, and whose changes to thymines would create stop codons (TAA, TAG, or TGA). Based on these criteria, we chose the 232nd cytosine (c.232 C) in the coding sequence, located in exon 3 of the chd gene (Fig. 1A), and c.178 C, located in exon 3 of the oep gene (Fig. 1B), as the targets for the nucleotide substitutions. It is notable that deamination rates of cytosines located at the -20, -19, -18, -17, and -16 positions from PAM sequences are estimated to be roughly 5, 25, 45, 35, and 5%, respectively, based on the Target-AID system using nCas9(D10A)-PmCDA1 in yeast16. Thus, in the case of oep targeting, c.175 C (-19 position) was expected to be deaminated more efficiently than c.178 C (-16 position).

Figure 1.

The design of the sgRNAs for the Target-AID system. Representations of the DNA sequences corresponding to the targeting sequences for (A) the chd sgRNA and (B) the oep sgRNA. (A,B) The uppercase letters in the DNA sequences represent exon sequences. The uppercase letters colored in red represent the target nucleotide. The lowercase letters represent intron sequences. The underlines represent the targeting sequences of the sgRNAs. The boxed sequences indicate the PAM sequence. The bold uppercase letters above the DNA sequences represent the single letter codes for amino acids.

Evaluation of the Target-AID system in zebrafish embryos

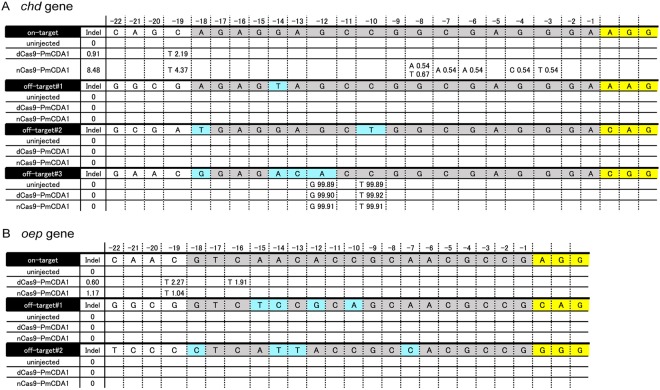

To investigate whether the Target-AID system induced C > T substitutions at the target site in injected embryos, we injected dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA or nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA with chd sgRNA into zebrafish embryos at the 1-cell stage and incubated the embryos until 3 days post fertilization (dpf). We then analyzed sixteen uninjected and sixteen injected embryos, all of which showed wild-type phenotypes, by deep sequencing (Fig. 2A). The uninjected embryos had no mutation around the target site in the chd locus. The dCas9-PmCDA1 and nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos contained targeted C > T substitutions at the -19 position (c.232 C) in the chd locus, with a frequency of 2.19% and 4.37%, respectively. Moreover, the nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos contained C > A, G > T, G > C, or G > A substitutions with low frequencies; each of these substitutions was observed less than 1% in all samples sequenced. Of note, insertions and deletions (indels) were detected approximately 9 times less frequently in the dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos (0.91%) than in the nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos (8.48%), which is consistent with previous reports in yeast and cultured cells16. Heteroduplex mobility assays (HMA) also revealed that dCas9-PmCDA1 induced fewer indel mutations in the chd locus than nCas9-PmCDA1 and Cas9 (Suppl. Fig. 1A–C). These results demonstrate that the Target-AID system is able to induce C > T substitutions predominantly at the target site in zebrafish embryos.

Figure 2.

The Target-AID system can induce nucleotide substitutions at the target site in injected embryos. DNA sequences aligned in a row represent the reference sequences of target and off-target regions (DanRer10). The targeting sequences, mismatched bases, and PAM sequences in the DNA sequences are highlighted in gray, light blue, and yellow, respectively. Mutational frequencies (%) at each nucleotide position (-22 to -1) from the PAM sequences are shown below the DNA sequences. (A) A mutation spectrum in the chd locus obtained by deep sequencing for uninjected embryos, dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, and nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos. (B) A mutation spectrum in the oep locus obtained by deep sequencing for uninjected embryos, dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, and nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos. On average, more than 90,000 reads were obtained per sample.

Next, to examine if the Target-AID system produced off-target mutations in zebrafish, we performed deep sequencing for potential off-target sites. The potential off-target sites were predicted by CCtop software (http://crispr.cos.uni-heidelberg.de/index.html)19 based on the off-target mismatch score. We selected both of the potential off-target sites with the canonical (5′–NGG–3′) and non-canonical PAM sequences (5′–NAG–3′), as we previously reported16. With respect to the chd sgRNA, we analyzed three potential off-target sites. These potential off-target sites have 1- to 4-base mismatches from the true target site. Deep sequencing revealed that off-target#1 and off-target#2 contained no mutations in the uninjected embryos, none in dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, and none in nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos (Fig. 2A). Off-target#3 had A > G and C > T substitutions at two positions (-10 and -12), both with almost 100% frequencies, which were most likely due to pre-existing single nucleotide polymorphisms rather than induced substitutions (Fig. 2A).

Next, we evaluated the oep gene locus (Fig. 2B). In each experiment, we analyzed sixteen embryos injected with oep sgRNA and dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA, or sixteen embryos injected with oep sgRNA and nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA, by deep sequencing. Collectively, as expected, targeted C > T substitutions were observed in the dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos (2.27% at the -19 position (c.175 C), and 1.91% at the -16 position (c.178 C)). In the nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, targeted C > T substitutions were detected only at the -19 position (1.04%). Indel mutations were detected approximately 2 times less frequently in the dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos (0.60%) than in the nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos (1.17%). Similar to what we observed in the chd locus, HMA assays revealed that dCas9-PmCDA1 induced fewer indel mutations in the oep locus than nCas9-PmCDA1 and Cas9 (Suppl. Fig. 1D–F). Thus, the Target-AID system can induce targeted C > T substitutions with few indels in the oep gene locus in zebrafish embryos.

We next examined off-target effects in the oep locus. For the oep sgRNA, we analyzed two potential off-target sites. The potential off-target sites predicted by CCtop contained 4-base mismatches from the true target site. Deep sequencing revealed that both the potential off-target sites contained no mutations in the uninjected embryos, none in the dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, and none in the nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos (Fig. 2B).

In summary, both constructs, dCas9-PmCDA1 and nCas9-PmCDA1, were able to induce targeted C > T substitutions in zebrafish embryos without apparent off-target effects, at least in the putative off-target sites. In particular, dCas9-PmCDA1 induced targeted C > T substitutions in both loci with fewer indel mutations than nCas9-PmCDA1 in zebrafish embryos. Importantly, the ratio of base substitutions to indel mutations20 with dCas9-PmCDA1 was higher than that with nCas9-PmCDA1 (in the chd locus, 2.41 for dCas9-PmCDA1 and 0.52 for nCas9-PmCDA1; and in the oep locus, 3.78 for dCas9-PmCDA1 and 0.97 for nCas9-PmCDA1). We therefore chose dCas9-PmCDA1 for the following experiments.

Generation of G0 adult zebrafish carrying the expected nucleotide substitutions

We injected dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA with the chd sgRNA or oep sgRNA into zebrafish embryos to generate G0 adult zebrafish (Suppl. Fig. 2). The adult fish are referred to as chd G0 fish or oep G0 fish, respectively. To investigate whether the G0 fish had the expected nucleotide substitutions at the target sites, PCR amplification of the targeted sequences was performed using genomic DNA from the caudal fins of five male chd G0 fish, and the PCR fragments were sequenced. Nucleotide substitutions were detected as extra peaks below the major peaks, likely due to mosaicism of the G0 fish (black and red arrowheads in Suppl. Fig. 3). In the analyses of chd G0 fish, two sequence patterns were obtained. One pattern, seen in three chd G0 fish, contained no detectable change (pattern (i) in Suppl. Fig. 3A); in the other pattern, two chd G0 fish had nucleotide substitutions at the target site, c.232 C (pattern (ii) in Suppl. Fig. 3A). No deletions were found around the target nucleotides in the chd gene. There were no detectable changes in non-targeted cytosines in the adjacent region around the target site in all analyzed chd G0 fish.

In the analyses of five male oep G0 fish, one fish had no detectable changes (pattern (i) in Suppl. Fig. 3B), and among the other fish, three types of nucleotide substitutions were observed (pattern (ii) to (v) in Suppl. Fig. 3B). The first type had a c.175 C > T substitution (black arrowheads in Suppl. Fig. 3B). The second type had a c.178 C > T substitution (red arrowheads in Suppl. Fig. 3B). In the third type, both c.175 C > T and c.178 C > T substitutions were present. Pattern (v), seen in one oep G0 fish, likely arose from mosaicism involving the expected nucleotide substitution of c.175 C and c.178 C, as well as at least one small deletion (Suppl. Fig. 3B). According to the experimental design, we expected that c.175 C and c.178 C, but no other nucleotide, would be mutated. Indeed, there were no detectable changes at other cytosines in the adjacent region around the target site in all analyzed oep G0 fish.

The induced nucleotide substitutions were mostly heritable in the next generation

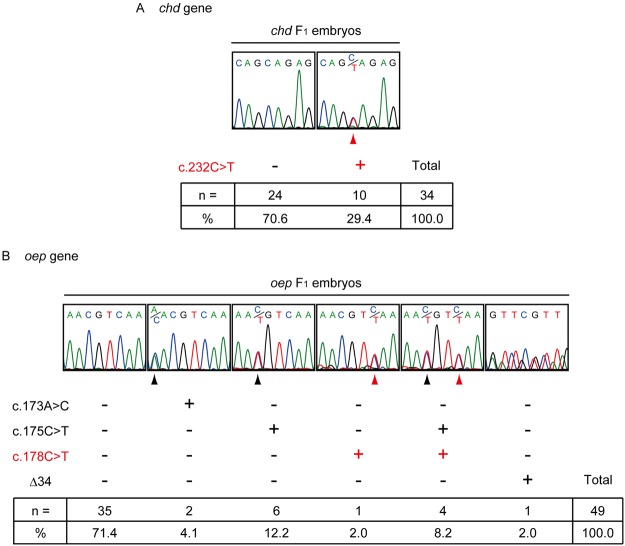

In order to examine whether the nucleotide substitutions induced by the Target-AID system in the G0 fish were heritable, genotyping of descendant embryos of the G0 fish was performed. Wild-type females were bred with the chd G0 fish or oep G0 fish (Suppl. Fig. 2), and descendant embryos were obtained from three chd G0 fish and four oep G0 fish (chd F1 embryos and oep F1 embryos, respectively). We then performed PCR amplification of the targeted sequences using genomic DNA from F1 embryos and sequenced the PCR products. Nucleotide substitutions were detected as superimposed peaks because the F1 embryos were mostly heterozygous at the target loci (black and red arrowheads in Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The nucleotide substitutions induced by the Target-AID system are heritable. Sequence patterns of (A) chd F1 embryos and (B) oep F1 embryos. The red arrowheads indicate nucleotide substitutions at the target site. The black arrowheads indicate nucleotide substitutions at untargeted sites. Observed frequencies and percentages of each genotype are shown in the panel.

Analysis of the genomic DNA from chd F1 embryos revealed two patterns in the chd loci (Fig. 3A). Expected c.232 C > T nucleotide substitutions were detected with a frequency of 29.4% (10/34). No detectable change was observed in the rest of the chd F1 embryos, 70.6% (24/34). Moreover, no other nucleotide substitutions were found within the sequenced regions. Germ line transmission of the modified allele was achieved in two of the three chd G0 fish (Suppl. Table 1).

From the analyses of oep F1 embryos from four oep G0 fish, we observed six patterns of sequence results (Fig. 3B): 1) 71.4% (35/49) of oep F1 embryos did not contain nucleotide changes; 2) 2.0% (1/49) contained a c.178 C > T substitution; 3) 12.2% (6/49) contained c.175 C > T substitutions; 4) 8.2% (4/49) contained both c.175 C > T and c.178 C > T substitutions; and 5) 2.0% (1/49) contained a deletion, detected in one sequencing result. Unexpectedly, in a sixth pattern two oep F1 embryos had a c.173 A > C substitution at a frequency of 4.1% (2/49). Three of the four oep G0 fish successfully transmitted the modified alleles (Suppl. Table 2). Note that one oep G0 fish with both the c.175 C > T and c.178 C > T substitutions (pattern (iv) in Fig. 3B) produced only wild-type F1 embryos (Fig. 3B and Suppl. Table 2). Taken together, these results indicate that the nucleotide substitutions induced by the Target-AID system are heritable.

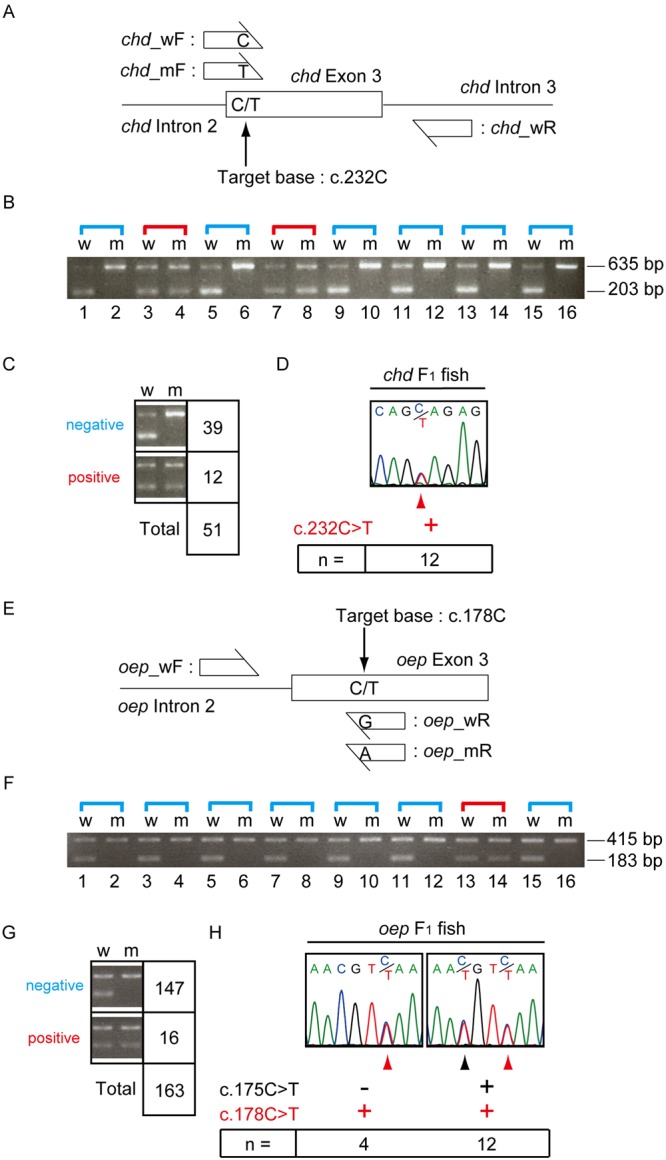

We next raised the rest of the F1 embryos to adulthood (Suppl. Fig. 2) and performed allele-specific PCR (Fig. 4A–C, E–G) and sequencing (Fig. 4D,H) to identify heterozygous F1 fish carrying the desired nucleotide substitutions at the target sites. For the identification of promising candidate heterozygous chd F1 fish carrying the c.232 C > T substitution (chdc.232C>T/+), we performed two PCR reactions using allele-specific primers, one for the wild-type allele (w) and the other for the mutated allele (m). Both produced 203 bp fragments (Fig. 4B,C). Another set of primers, which was designed to amplify the chd gene outside of the target site, was also included in the PCR reaction. This produced 635 bp DNA fragments as internal positive controls (Fig. 4B,C). When the 203 bp DNA fragment was detected only in a “w” lane, the result indicated that the fish did not carry the c.232 C > T substitution, and the fish was scored as a “negative” or “wild-type” fish (chd+/+ fish). If the 203 bp DNA fragments were detected in both “w” and “m” lanes, the fish was heterozygous, and was scored as “positive” or “mutated” (chdc.232C>T/+ fish). In total, we identified 39 “negative” (chd+/+) and 12 “positive” (chdc.232C>T/+) fish (Fig. 4C). Sequencing of the targeted region in the 12 positive fish confirmed the c.232 C > T substitution in all 12 fish (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Identification of heterozygous fish carrying the expected nucleotide substitution at the target site. (A) Schematic representation of allele-specific PCR analysis of the chd gene. (B) An example of the results after allele-specific PCR amplification of the chd gene. The 203 bp DNA fragments in the”w” lanes were amplified by the primer set of chd_wF and chd_wR primers, whereas fragments in the “m” lanes were amplified by the primer set chd_mF and chd_wR. The 635 bp DNA fragments were amplified by a primer set recognizing a different region of the chd gene as an internal control. (C) Results of analyzing all individuals by allele-specific PCR for the chd gene. “Negative” indicates the absence of a nucleotide substitution at the target site, while “positive” indicates the presence of a nucleotide substitution at the target site. (D) Results of analyzing 12 positive individuals by sequencing the targeted region of the chd gene. (E) Schematic representation of allele-specific PCR analysis for the oep gene. (F) An example of results after allele-specific PCR amplification of the oep gene. The 183 bp DNA fragments in the”w” lanes were amplified by the primer set oep_wF and oep_wR, whereas fragments in the “m” lanes were amplified by the primer set oep_wF and oep_mR. The 415 bp DNA fragments were amplified by a primer set recognizing a different region of the oep gene as an internal control. (G) Results of analyzing all individuals by allele-specific PCR for the oep gene. (H) Results of analyzing 16 positive individuals by sequencing the targeted region of the oep gene. (D,H) The red arrowheads indicate the nucleotide substitution at the target site. (H) The black arrowhead indicates the nucleotide substitution at the untargeted site.

We next examined oep F1 fish to identify candidate heterozygotes carrying the C > T nucleotide substitution (oepc.178C>T/+ fish) (Fig. 4E–G). For this purpose, we used sets of allele-specific primers for the wild-type allele (w) or for the mutated allele (m) (183 bp fragments in Fig. 4F,G), and another set of control primers (415 bp fragments in Fig. 4F,G), and performed allele-specific PCR. We found 147 (oep+/+) and 16 (oepc.178C>T/+) fish (Fig. 4G). Sequencing of the targeted region in the 16 (oepc.178C>T/+) fish revealed that 12 fish were compound heterozygotes with c.175 C > T and c.178 C > T substitutions, and 4 were heterozygotes for the c.178 C > T substitution only (Fig. 4H).

The nucleotide substitutions at target cytosines recapitulate typical mutant phenotypes

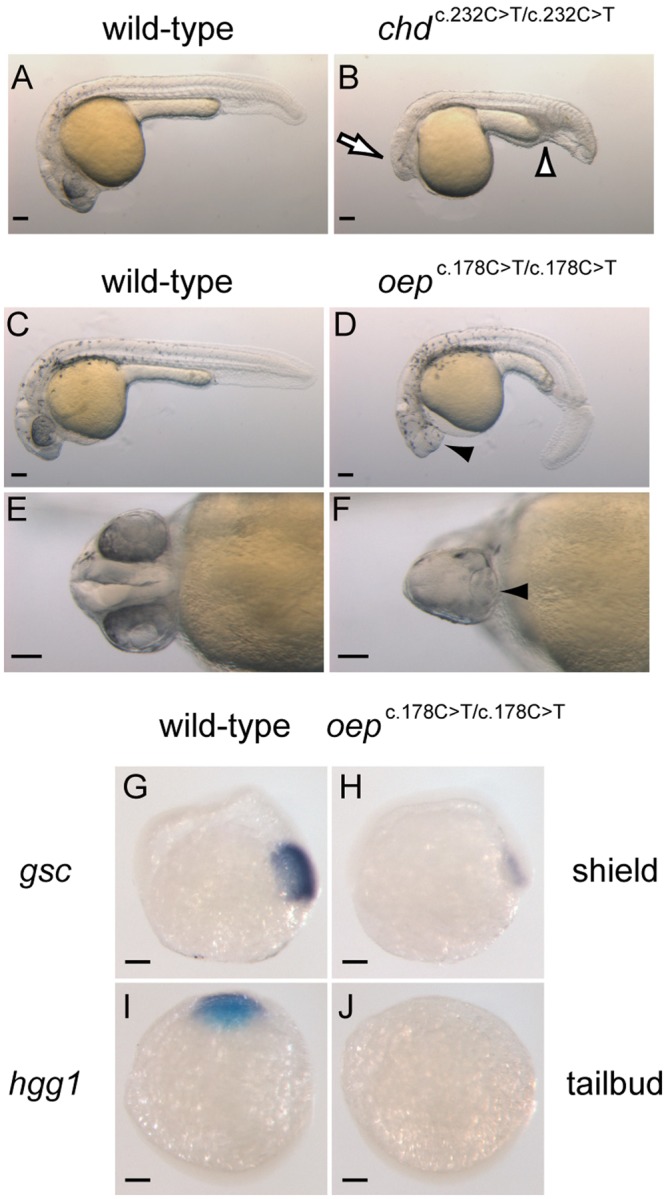

Next, we bred a pair of chdc.232C>T/+ fish or a pair of oepc.178C>T/+ fish to produce F2 embryos (Suppl. Fig. 2). As described above, the c.232 C > T and c.178 C > T nucleotide substitutions in the chd and oep genes, respectively, create premature stop codons (Fig. 1). Thus, the F2 embryos with homozygous mutations should display well-known phenotypes: chd mutants have small heads and expanded blood islands21, and oep mutants have single eyes22. The breeding experiments revealed that typical chd mutant and oep mutant phenotypes were observed in 28.4% (61/215) and 21.6% (68/315) of the F2 embryos, respectively. These results fit well with a recessive mode of Mendelian inheritance. Sequence analyses of the genomes of these embryos revealed the expected genotypes, namely F2 embryos with small heads and expanded blood islands were chdc.232C>T/c.232C>T homozygotes (Fig. 5B compared with 5A), and F2 embryos with single eyes were oepc.178C>T/c.178C>T homozygotes (Fig. 5D,F, compared with 5C,E, respectively).

Figure 5.

The Target-AID system can generate nucleotide substitution mutants. Phenotypic representation of (A, lateral view) a wild-type embryo and (B, lateral view) a chdc.232C>T/c.232C>T F2 embryo at 24 hpf. The open arrow and open arrowhead indicate a smaller head and expanded blood islands, respectively. Phenotypic representation of (C, lateral view), (E, ventral view) a wild-type embryo and (D, lateral view), (F, ventral view) an oepc.178C>T/c.178C>T F2 embryo at 27 hpf. The arrowhead indicates a single eye in each respective panel. (G,H) Expression pattern of gsc in (G, lateral view) a wild-type embryo and (H, lateral view) an oepc.178C>T/c.178C>T F2 embryo at the shield stage. (I,J) Expression pattern of hgg1 in (I, dorsal view) a wild-type embryo and (J, dorsal view) an oepc.178C>T/c.178C>T F2 embryo at the tailbud stage. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

To further characterize oepc.178C>T/c.178C>T F2 embryos, we performed whole mount in situ hybridizations with RNA probes for goosecoid (gsc), a molecular marker for the organizer, and hatching gland 1 (hgg1), a molecular marker for anterior dorsal mesoderm (Fig. 5G–J). The expression of gsc was suppressed at the shield stage in oepc.178C>T/c.178C>T embryos (Fig. 5H compared with 5G). This observation was consistent with a previous study22. Moreover, the expression of hgg1 was absent at the tailbud stage in oepc.178C>T/c.178C>T embryos (Fig. 5J compared with 5I). These observations are also consistent with previously described phenotypes of oep mutants22, demonstrating that oepc.178C>T/c.178C>T embryos recapitulate mesodermal defects characteristic of oep mutant embryos. These results, as a whole, convincingly show that the Target-AID system can introduce a targeted single-nucleotide substitution from cytosine to thymine in vivo in a vertebrate.

Discussion

It has been shown that the Target-AID system16 and another nucleotide editing system20 deliver single-nucleotide alterations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian cultured cells. The Target-AID system is based on the CRISPR/Cas9 system16 which functions as a powerful tool for gene knockouts in various kinds of vertebrates, such as medaka18, Xenopus23,24, and mouse25,26 as well as invertebrates27,28. Therefore, programmable single-nucleotide editing of genomic DNA in these various organisms should be amenable to the Target-AID system. Indeed, we show in this study that the Target-AID system can induce heritable nucleotide substitutions in zebrafish in vivo.

We evaluated two versions of the Target-AID system, dCas9-PmCDA1 and nCas9-PmCDA1, in zebrafish embryos. In a previous study of the Target-AID system, formation of nicks on the non-deamination strand of target DNA appeared to improve the frequency of C > T substitutions at the target sites16. Deep sequencing in injected embryos in the present study revealed that DNA nicking by nCas9-PmCDA1 improved the frequency of targeted C > T substitutions in the chd locus in zebrafish embryos, but not in the oep locus. Moreover, nCas9-PmCDA1 induced C > A, G > T, G > C, or G > A substitutions in addition to C > T substitutions in the chd locus, and increased indel mutations to a level that we consider problematic (Fig. 2 and Suppl. Fig. 1). In fact, indel mutations in zebrafish were observed in another nCas9-based base editing (BE) method, which induced C > T substitutions29. In sharp contrast, we observed efficient targeted C > T substitutions and hardly observed indel mutations with dCas9-PmCDA1, as compared to nCas9-PmCDA1. These results suggest that the Target-AID system using dCas9-PmCDA1 provides a safer single-nucleotide-editing method, as compared to nCas9-PmCDA1, for therapeutic applications in animals.

Deep sequencing of G0 embryos and analyses of F1 embryos revealed that the nucleotide substitutions at the target sites occurred with different frequencies. These differences may be dependent on the distances from the PAM sequences. With the chd gene, dCas9-PmCDA1 yielded the c.232 C > T mutation at the -19 position from the PAM sequence at a frequency of 2.19% in G0 embryos (Fig. 2A). With the oep gene, the c.175 C > T substitution (at position -19 with respect to the PAM) and the c.178 C > T substitution (at position -16 with respect to the PAM) were induced by dCas9-PmCDA1 in G0 embryos at frequencies of 2.27% and 1.91%, respectively (Fig. 2B). In F1 embryos, the chd c.232 C > T mutation was obtained at an overall frequency of 29.4% (10/34), and this was the sole mutation that was obtained (Fig. 3A). The c.175 C > T substitution was present in 20.4% of the oep F1 embryos, and the c.178 C > T substitution was present in 10.2% of the oep F1 embryos (Fig. 3B) when including compound heterozygotes with both -19 and -16 substitutions. These frequencies, in particular in F1 embryos, were reminiscent of those observed in a Target-AID system, using nCas9(D10A)-PmCDA1 in yeast16; with the yeast system, nucleotide substitutions of cytosines occurred at the -19 position at a frequency of about 25%, and substitutions at the -16 position occurred with a frequency of about 5%. Our results suggest that, even in zebrafish, the relative distance from the PAM affects the efficiency of cytidine deamination. Our results also indicate that candidate regions for targeted mutations should ideally have only one cytosine, in order to avoid redundant modifications.

Interestingly, base substitution rates in germ lines were higher than those of whole embryos in deep sequencing (Fig. 3A,B compared with Fig. 2A,B). Our observation suggests that base substitutions by dCas9-PmCDA1 might occur more effectively in germline cells than in somatic cells.

We also found A > C substitutions in the oep F1 embryos (Fig. 3B). The previous study reported that the A > C substitutions induced by the Target-AID system are rare (less than 1%)16. A deaminated adenine (hypoxanthine) is capable of base pairing with cytosine in E. coli, resulting in an A > G mutation30. However, this mechanism cannot explain the A > C substitution that we observed in the present study. A deletion event was also observed, even though nuclease-dead Cas9 was used for targeting (Figs 2, 3B, Suppl. Figs 1, and 3B). Deletion events with the Target-AID system using dCas9-PmCDA1 were also detected in the previous study at a frequency of less than 1%16. This deletion might be due to the sequence context in the targeted region and/or epigenetic modifications of the target loci. Further studies are needed for a detailed understanding of the rare A > C substitutions and deletions induced by the Target-AID system.

Off-target assessments in G0 embryos revealed that the Target-AID system did not appear to create off-target mutations, at least in the putative off-target sites we examined (Fig. 2). These results indicate that strict base-pair matching is required for the induction of C > T substitutions in zebrafish. Of course, there is a slight possibility that some of the injected embryos might die by 3 dpf because of unpredictable off-target effects. Further analysis about off-target effects of the Target-AID system is required to more precisely evaluate the Target-AID system in vivo.

G0 fish whose caudal fins possessed the desired nucleotide substitutions did not always transmit the nucleotide substitutions to their F1 descendants. The results are consistent with the possibility of mosaicism, where different nucleotide substitutions occurred in each daughter cell after the cell division of the zygote co-injected with the dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA and sgRNA. The results also indicate that the genotype of cells in caudal fins is not a perfect indicator of germline transmission.

In addition to the creation of premature stop codons, as shown in this study, the Target-AID system has a potential to regulate transcription and splicing in vivo. It is difficult to make suitable precise modifications at promoter/enhancer regions or splicing sites by the regular CRISPR/Cas9 system because the CRISPR/Cas9 system induces uncontrolled DSBs. In contrast, the Target-AID system may allow researchers to modulate the promoter/enhancer activities and splicing pattern/efficiency by the substitutions of appropriate target cytosines with thymines in the promoter/enhancer and splicing sites, respectively. In this regard, the Target-AID system may provide an opportunity for therapeutic treatment by regulating gene expression and/or splicing. Future efforts will be directed toward overcoming the limitation of the PAM recognition, etc., to achieve nucleotide substitutions at any desired position of the genome.

Methods

Zebrafish

Zebrafish were maintained as described in a previous study31. Wild-type embryos were obtained by breeding AB strain males and females. All zebrafish experiments were performed under the ethical guidelines of Kyoto University and approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Kyoto University (No. Inf-K14001).

mRNA synthesis

The DNA coding sequences for dCas9-NLS-FLAG-PmCDA1 (dCas9-PmCDA1), and nCas9-NLS-FLAG-PmCDA1 (nCas9-PmCDA1) were amplified by PCR with the following primer set: 5′-TCTTTTTGCAGGATCATGGACAAGAAGTAC-3′, and 5′-GAGAGGCCTTGAATTGGATCCTTATCCGGA-3′. The PCR products were cloned into the pCS2+ vector using the InFusion method (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan). The resulting pCS2+ dCas9-PmCDA1, the pCS2+ nCas9-PmCDA1, and the pCS2+ Cas9 plasmid was linearized with NotI. Capped mRNA encoding dCas9-PmCDA1, nCas9-PmCDA1, and Cas9 was synthesized in vitro from the SP6 promoter using a mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Single guide RNA synthesis

For synthesis of sgRNAs with customizable 18-nucleotide targeting sequences, we used the oligonucleotide pairs listed in Suppl. Table 3. Each oligonucleotide pair was annealed at 25 °C for 1 h after incubation at 95 °C for 2 min. The annealed oligonucleotides were ligated into BsaI-digested pDR274 vector18,32 with Ligation high Ver.2 (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). After the ligated products were linearized with DraI, sgRNAs were synthesized in vitro using MEGAshortscript T7 Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA injection

Approximately 1 nl of the following mixed solutions was microinjected into the cytoplasm of 1-cell stage zebrafish embryos: dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA + chd sgRNA (100 ng/μl dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA, 25 ng/μl chd sgRNA); nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA + chd sgRNA (100 ng/μl nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA, 25 ng/μl chd sgRNA); Cas9 mRNA + chd sgRNA (100 ng/μl Cas9 mRNA, 25 ng/μl chd sgRNA); dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA + oep sgRNA (100 ng/μl dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA, 25 ng/μl oep sgRNA); nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA + oep sgRNA (100 ng/μl nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA, 25 ng/μl oep sgRNA); and Cas9 mRNA + oep sgRNA (100 ng/μl Cas9 mRNA, 25 ng/μl oep sgRNA). For the chd sgRNA, on average, 96.6% of uninjected embryos, 77.8% of dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, 76.4% of nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, and 61.4% of Cas9 mRNA-injected embryos showed apparently normal phenotypes at 3 dpf. For the oep sgRNA, on average, 95.2% of uninjected embryos, 67.3% of dCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, 57.6% of nCas9-PmCDA1 mRNA-injected embryos, and 47.2% of Cas9 mRNA-injected embryos showed apparently normal phenotypes at 3 dpf. Injected embryos with apparently normal phenotypes were used for deep sequencing and the heteroduplex mobility assays described below.

Fin amputation

Adult zebrafish were anesthetized in 0.6 mM Tricaine solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, USA). Zebrafish caudal fins were amputated with a surgical blade (No. 10, FEATHER Safety Razor, Mino, Japan).

Genomic DNA preparation

For genomic DNA preparation, amputated caudal fins of adult fish or whole single embryos at 1–3 dpf were lysed essentially as described18. The lysates were used for PCR amplification.

Deep sequencing of target and off-target sites in zebrafish embryos

Genomic DNA, extracted from each zebrafish embryo at 3 dpf, was used as template DNA for primary PCR amplification. Deep sequencing was carried out as previously described16. The primers used for deep sequencing are listed in Suppl. Table 3. After nested PCR, index sequences were added to the amplicons. The index sequences were matched to samples as described in Suppl. Table 4. Sequencing reactions were performed with a MiniSeq sequencing system (Illumina, CA, USA) to obtain paired 151 bp read lengths. The obtained reads were mapped to each reference sequence from the zebrafish genome database (DanRer10) by the following setting: Masking mode = no masking; Mismatch cost = 2; Insertion cost = 3; Deletion cost = 3; Length fraction = 0.5; Similarity fraction = 0.8; Global alignment = No; Auto detect paired distances = Yes; Nonspecific match handling = Map randomly. The variant calling was performed with the following settings: Ignore positions with coverage = 150,000; Ignore broken pairs = Yes; Ignore Nonspecific matches = Reads; Minimum coverage = 10; Minimum count = 2; Minimum frequency = 0.5%; Base quality filter = No; Read detection filter = No; Relative read direction filter = 0.5%; Read position filter = No; Remove pyro-error variants = No. Rearrangement of the output file was made using Excel (Microsoft, WA, USA).

Heteroduplex mobility assay

Heteroduplex mobility assays (HMA) were performed essentially as described in a previous study18. Targeting sequences in the chd and oep loci were amplified with BIOTAQ DNA Polymerase (Bioline, London, UK) and with primer sets listed in Suppl. Table 3. The primer sets produce 117 bp DNA fragments for the chd locus, and 132 bp DNA fragments for the oep locus. The DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis in an 8.0% acrylamide gel.

Genotyping by sequencing

PCR amplification of the targeting sequences in the chd and oep genes was performed with BIOTAQ DNA Polymerase (Bioline, London, UK) and with primer sets listed in Suppl. Table 3. PCR was carried out with the following parameters: for the chd gene, a pre-denaturation of 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of amplification (94 °C for 20 s, 62 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 20 s), and a final extension at 72 °C for 1 min; for the oep gene, a pre-denaturation of 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of amplification (94 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 20 s), and a final extension at 72 °C for 1 min. The PCR products from the chd and oep amplifications were purified with NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) and sequenced by Fasmac (Atsugi, Japan) or by Macrogen Japan (Kyoto, Japan) with the chd_1st_F and oep_1st_F primers, respectively.

Genotyping by allele-specific PCR

Primers used in allele-specific PCR33 are listed in Suppl. Table 3. The chd_wF and the chd_mF primers were designed to anneal to the antisense strand of intron 2 and exon 3 in the chd gene, while the chd_wR primer to the sense strand of intron 3 in the chd gene. The 3′ ends of both of the forward primers were designed to anneal to the target nucleotide, c.232 C, in the chd gene. The chd_wF primer has a C residue at the 3′ end, while the chd_mF primer has a T residue at the 3′ end. Moreover, a T residue two nucleotides from the 3′ ends of both of the forward primers generates a template/primer C/T mismatch. The oep_wF primer was designed to anneal to the antisense strand of intron 2 in the oep gene, while the oep_wR and oep_mR primers to the sense strand of exon 3 in the oep gene. The 3′ ends of both of the reverse primers were designed to anneal to the target nucleotide, c.178 C, in the oep gene. The oep_wR primer has a G residue at the 3′ end, while the oep mR primer has an A residue at the 3′ end. The primer sets of chd_bF and chd_bR, and oep_bF and oep_bR were used for internal controls to amplify DNA sequences 800–1400 bp downstream of the target nucleotides.

Alelle-specific PCR for the target nucleotides in the chd and oep genes was performed with BIOTAQ DNA Polymerase (Bioline, London, UK) with the following PCR parameters: for the chd gene, a pre-denaturation of 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of amplification (94 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 20 s) and a final extension at 72 °C for 1 min; for the oep gene, a pre-denaturation of 94 °C for 5 min, 25 cycles of amplification (94 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 20 s) and a final extension at 72 °C for 1 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in a 2.0% agarose gel.

Phenotypic observation of zebrafish embryos

The phenotypes of F2 embryos were observed at 24 hours post fertilization (hpf) for the chd mutant embryos and at 27 hpf for the oep mutant embryos. Images of the embryos were taken under a SZX16 stereo microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a MicroPublisher 5.0 camera (QImaging, Surrey, Canada).

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Each RNA probe was synthesized to detect gsc, or hgg1 endogenous mRNA, as described previously34. Whole mount in situ hybridization was performed by a protocol described previously35. Genomic DNA from each embryo was extracted essentially as described36. The genotype of each embryo was determined by allele-specific PCR.

Data availability

Data obtained by deep sequencing have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), and the accession code is SRP140583. The remaining data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kinoshita for kindly providing the pCS2+ Cas9 vector. We also thank our lab members for maintaining our fish facility. S.M. was supported by a Grant-in-aid for Young Scientists (A) No. 22687016 and for Exploratory Research No. 24657102. This work was partly supported by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO).

Author Contributions

S.T., S.M., K.N. and H.H. designed the research and S.T., S.Y. and S.M. carried out the experiments. S.T., S.M., H.H. and A.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors analyzed and discussed the results.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-29794-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kim YG, Cha J, Chandrasegaran S. Hybrid restriction enzymes: Zinc finger fusions to Fok I cleavage domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:1156–1160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christian M, et al. Targeting DNA Double-Strand Breaks with TAL Effector Nucleases. Genetics. 2010;186:757–U476. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jinek M, et al. A Programmable Dual-RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox DBT, Platt RJ, Zhang F. Therapeutic genome editing: prospects and challenges. Nature Medicine. 2015;21:121–131. doi: 10.1038/nm.3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding QR, et al. Permanent Alteration of PCSK9 With In Vivo CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing. Circulation Research. 2014;115:488–+. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin, S. R. et al. The CRISPR/Cas9 System Facilitates Clearance of the Intrahepatic HBV Templates In Vivo. Molecular Therapy-Nucleic Acids 3 10.1038/mtna.2014.38 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Tebas P, et al. Gene Editing of CCR5 in Autologous CD4 T Cells of Persons Infected with HIV. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:901–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakondi B, et al. In Vivo CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing Corrects Retinal Dystrophy in the S334ter-3 Rat Model of Autosomal Dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa. Molecular Therapy. 2016;24:556–563. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson CE, et al. In vivo genome editing improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science. 2016;351:403–407. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwank G, et al. Functional Repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in Intestinal Stem Cell Organoids of Cystic Fibrosis Patients. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu YX, et al. Correction of a Genetic Disease in Mouse via Use of CRISPR-Cas9. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long CZ, et al. Prevention of muscular dystrophy in mice by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of germline DNA. Science. 2014;345:1184–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.1254445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Ravin SS, et al. Targeted gene addition in human CD34(+) hematopoietic cells for correction of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Nature Biotechnology. 2016;34:424–+. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich T, Allen RL, Wyllie AH. Defying death after DNA damage. Nature. 2000;407:777–783. doi: 10.1038/35037717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nambiar M, Raghavan SC. How does DNA break during chromosomal translocations? Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:5813–5825. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishida K, et al. Targeted nucleotide editing using hybrid prokaryotic and vertebrate adaptive immune systems. Science. 2016;353:1248-+. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muramatsu M, et al. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ansai S, Kinoshita M. Targeted mutagenesis using CRISPR/Cas system in medaka. Biology Open. 2014;3:362–371. doi: 10.1242/bio.20148177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stemmer, M., Thumberger, T., Keyer, M. d. S., Wittbrodt, J. & Mateo, J. L. CCTop: An Intuitive, Flexible and Reliable CRISPR/Cas9 Target Prediction Tool. Plos One1010.1371/journal.pone.0124633 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533:420–+. doi: 10.1038/nature17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammerschmidt M, et al. dino and mercedes, two genes regulating dorsal development in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1996;123:95–102. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schier AF, Neuhauss SCF, Helde KA, Talbot WS, Driever W. The one-eyed pinhead gene functions in mesoderm and endoderm formation in zebrafish and interacts with no tail. Development. 1997;124:327–342. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blitz IL, Biesinger J, Xie XH, Cho KWY. Biallelic Genome Modification in F-0 Xenopus tropicalis Embryos Using the CRISPR/Cas System. Genesis. 2013;51:827–834. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakayama T, et al. Simple and Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Targeted Mutagenesis in Xenopus tropicalis. Genesis. 2013;51:835–843. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen B, et al. Generation of gene-modified mice via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting. Cell Research. 2013;23:720–723. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang HY, et al. One-Step Generation of Mice Carrying Mutations in Multiple Genes by CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Genome Engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedland AE, et al. Heritable genome editing in C. elegans via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nature Methods. 2013;10:741–+. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gratz SJ, et al. Genome Engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-Guided Cas9 Nuclease. Genetics. 2013;194:1029–+. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, Y. H. et al. Programmable base editing of zebrafish genome using a modified CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nature Communications810.1038/s41467-017-00175-6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Nordmann PL, Makris JC, Reznikoff WS. Inosine induced mutations. Molecular & General Genetics. 1988;214:62–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00340180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aoyama Y, et al. A Novel Method for Rearing Zebrafish by Using Freshwater Rotifers (Brachionus calyciflorus) Zebrafish. 2015;12:288–295. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2014.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang WY, et al. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nature Biotechnology. 2013;31:227–229. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newton CR, et al. Analysis of any point mutation in DNA - The amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) Nucleic Acids Research. 1989;17:2503–2516. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maegawa S, Varga M, Weinberg ES. FGF signaling is required for beta-catenin-mediated induction of the zebrafish organizer. Development. 2006;133:3265–3276. doi: 10.1242/dev.02483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka S, Hosokawa H, Weinberg ES, Maegawa S. Chordin and dickkopf-1b are essential for the formation of head structures through activation of the FGF signaling pathway in zebrafish. Developmental biology. 2017;424:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gansner JM, Madsen EC, Mecham RP, Gitlin JD. Essential Role for fibrillin-2 in Zebrafish Notochord and Vascular Morphogenesis. Developmental Dynamics. 2008;237:2844–2861. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data obtained by deep sequencing have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), and the accession code is SRP140583. The remaining data are available from the corresponding author upon request.