Abstract

Background: In November 2009, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) changed their mammography screening guidelines from recommending a screen every 1–2 years for women older than 40 years. The revised guideline recommends against regular screening for women aged 40–49 and recommends biennial screening for women aged 50–74.

Research Design: We used autoregressive integrated moving-average (ARIMA) time series modeling to estimate the effect of the USPSTF 2009 guidelines on trends in screening rates. Enrollment and encounter files from the PharMetrics LifeLink+ commercial insurance claims database, years 2006–2014, were linked to determine monthly screening rates. The main outcome measure was mammography screening rates per 1,000 commercially insured women aged 40–49 or aged 50–64.

Results: The study sample included 493,347 women aged 40–49 years with at least 1 month of eligibility and 658,052 women aged 50–64 years with at least 1 month of eligibility. There were 1,305,375 total screening mammograms from 2007 to 2014. Average monthly mammography screening rates from 2007 to 2014 were 40.4 per 1,000 women aged 40–49 and 54.8 per 1,000 women aged 50–64. There was a temporary decline in monthly screening rates of 11.8% and 11.2% for the 40–49 and 50–64 age groups, respectively, in the 2-month period after the guideline change (January and February 2010), but the rates quickly returned to pre-USPSTF trend levels afterward.

Conclusion: Implementation of the USPSTF 2009 guidelines was not associated with a persistent long-term change in mammography screening rates over the next 5 years, despite a temporary decline of 2 months immediately following the guidelines.

Keywords: : mammography, screening, USPSTF, time series

Introduction

Excluding some types of skin cancer, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women. An estimated one in eight women will develop breast cancer over her lifetime.1 In 2012, the incidence of female breast cancer was 122.2 cases per 100,000 women, and 41,150 women died from breast cancer in that year alone.2 In addition to the morbidity and mortality of breast cancer, this disease also causes a significant economic burden. The 2010 national estimated cost of breast cancer was $16.5 billion, and it is anticipated that annual costs may be as high as $25.6 billion by 2020.3

The use of mammography screening has been found to reduce breast cancer mortality4,5; however, there has been increased controversy regarding the appropriateness of annual mammography screening because of the relatively large number of women who need to be screened to reduce mortality, the overdiagnosis of nonfatal breast cancer, and the increased anxiety caused by abnormal screening results.6–8 It has been suggested that mammography screening at rates higher than recommended may result in this overdiagnosis and more false positive test results, which may lead to an increase in unnecessary clinical testing, treatment, and psychosocial consequences.9,10

Based on these concerns, in 2009, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) changed their guidelines to reduce the overall frequency of mammography screening of women older than 40 years, including a recommendation against routine mammography screening for women aged 40–49. Before 2009, the USPSTF recommended all women aged 40 and older receive mammography screening every 1–2 years.11,12 Starting in 2009, it was recommended that for women younger than 50 years, routine screening should be based on the patient's individual context and should take into account “the patient's values regarding specific benefits and harms,” and that for women older than 75 years, there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against regular screening.11 The USPSTF maintained that women between ages 50–74 should receive biennial screening.

Previous studies evaluating changes in screening mammography of the USPSTF guideline change yielded mixed results. To our knowledge, no other study used data beyond 2012.12–19 This study utilized a nationally representative database of commercially insured individuals. Studies that use clinical claims-level databases may be better able to measure mammography utilization than patient-reported surveys, which are subject to participant recall bias. One of the greatest advantages of using claims data is the ability to capture data points at more granular time intervals. In addition, algorithms can be used to distinguish screening from diagnostic mammograms by identifying previous breast cancer diagnoses or treatments.13,16 The goal of this study was to evaluate the long-term impact of the USPSTF guideline on screening mammography rates.

Methods

This study used the IMS PharMetrics Lifelink+ database. This longitudinal database links health insurance enrollment and adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims for 150 million individuals nationwide.20 The PharMetrics Lifelink+ database has been found to be representative of the commercially insured population younger than 65 years in the United States, with respect to geographic region, age, sex, and health plan type.21,22 The data include all adjudicated claims for inpatient and outpatient procedural and diagnoses codes, pharmaceutical prescriptions, and demographic information (e.g., age, geographic region, provider specialty, and health plan enrollment information).23

A 10% random sample of recipients' inpatient, outpatient, and ancillary claim files from 2006 to 2014 was used to identify screening mammograms, with the first year (2006) used as a lookback period. Our study population consisted of women who resided in any of the 50 United States or the District of Columbia (DC), who were aged 40–64 at any point from 2007 to 2014 and were enrolled in commercial insurance for at least 12 months before the month in which the mammography rate was calculated. Because PharMetrics LifeLink+ is representative of the commercially insured adults younger than 65 years, women aged 65 or older were not included in monthly mammography rate calculations.

The sole use of procedural codes to specify a mammography as diagnostic or screening has been found to unreliably distinguish between the two services.24,25 At least two studies have derived and reported validity statistics for claim-based algorithms to discriminate between screening and diagnostic mammograms.26,27 These two algorithms are similar in their structure and calculation; however, we chose the 3-step algorithm26 because it demonstrates a comparable sensitivity (97.1% vs. 99.9%) and higher specificity (69.4% vs. 34.1%), and it was validated in a population similar to ours (i.e., not restricted to women with a previous breast cancer diagnosis). For step one of the algorithm, we selected claims coded as screening mammograms in which the woman had at least 1 year of prior commercial insurance enrollment. Step two removed screens in which the woman had a screening or diagnostic mammogram claim within 9 months (270 days) before the screen. Finally, step three removed screens in which the woman had a breast cancer diagnosis claim within 1 year (365 days) before the screen. Steps two and three were designed to exclude mammograms coded as screens that were, in all likelihood, diagnostic mammograms performed as a follow-up to a prior, abnormal mammogram result or cancer diagnosis.26

Claims were flagged as representing a bilateral screening mammogram (Current Procedural Terminology-4 (CPT-4) codes 76057 or 76092, or International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes V76.11 or V76.12), a diagnostic mammogram (CPT codes 76090, 76091, 77055, or 77056), or a breast cancer diagnosis (ICD-9 diagnosis codes 174.x, 230.0, or V103).12,26

The database could contain multiple claims per day for an individual and we conservatively ordered and selected the claims hierarchically. When multiple claims were observed on the same day for the same patient, screening mammograms were kept for that day only if there was no breast cancer diagnosis or diagnostic mammogram. This prioritization impacted 0.73% of our total included claims and 0.51% of claims with any screening mammography code.

The monthly rate of mammography screening was measured as the number of screenings per 1,000 eligible women. A woman was considered ineligible for a given month if she had a screening or diagnostic mammography within the previous 9 months or a breast cancer diagnosis within the previous year, or if she did not have 12 months of commercial insurance coverage before that month. Monthly mammography screening rates were calculated for women aged 40–49 and for women aged 50–64, such that a woman who turned 50 (based on year of birth) transitioned from the younger to the older age category for both the numerator and the denominator in the same month.

To evaluate the impact of the mammography guideline change on monthly screening rates per 1,000 eligible women, the 3 years before the USPSTF guideline change were used to forecast the counterfactual estimate of screening rates in the 5 years following the guideline. An autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model was fit for each age group using the Box-Jenkins approach.28 We determined the best fitting ARIMA (p, d, q) model through an iterative process of identifying, estimating, and evaluating each model's parameters to account for trends and serial autocorrelation. This analytic process was used rather than a simpler OLS regression technique because the screening rate in a particular month appeared to be dependent on the rate in previous months.29,30

Initial plots of the raw monthly rates before the USPSTF guideline change were used to determine integration parameters necessary to create stationary (i.e., constant) rates across the time period. These plots indicated that the integration parameter should be 1 in each of the models. Autoregressive and moving average terms were iteratively added to the model based on inspecting the autocorrelation function and the partial autocorrelation function. The best model fit was chosen by evaluating the level of white noise in the residuals according to nonsignificant Ljung-Box q-statistic values and by comparing Akaike information criterion using the conditional least-squares method.

An ARIMA (12,1,0) model differenced at lag 1 (DF test ρ = −63.5, p = 0.0002 at lag 1) and with autoregressive terms (p) at lags 1 and 12 was found to be the best fitting model for the 40–49 year-old age group (Table 1). An ARIMA (12,1,2) model differenced at lag 1 (DF test ρ = −89.6, p = 0.0002 at lag 1), with autoregressive terms at lags 1 and 12, and with a moving average at lag 2 was found to be the best fitting model for the 50–64 year-old age group (Table 1). The actual values were compared to the counterfactual forecasts with 95% confidence intervals estimated.

Table 1.

Parameter Estimates from Base Case Forecast Time Series ARIMA Models

| 40–49 year-old ARIMA model | 50–64 year-old ARIMA model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | T-value | p-value | Estimate | Standard Error | T-value | p-value |

| B0, intercept | 0.1040 | 0.3805 | 0.27 | 0.7865 | 0.1911 | 0.2985 | 0.64 | 0.5268 |

| AR(1) | −0.5279 | 0.1288 | −4.10 | 0.0003 | 0.3850 | 0.2047 | 1.88 | 0.0694 |

| AR(12) | 0.4597 | 0.1486 | 3.08 | 0.0041 | −0.6509 | 0.1330 | −4.89 | <.0001 |

| MA(2) | — | — | — | — | 0.3492 | 0.1347 | 2.59 | 0.0144 |

ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average; MA, moving average; AR, autoregressive.

Sensitivity analyses

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted. The first approach reestimated the ARIMA parameters and incorporated nonstochastic terms to evaluate the impact of USPSTF guideline changes using a traditional interrupted time series approach. For the 40–49 year-old age group, an ARIMA (12, 0, and 1) model with autoregressive terms at lags 1, 3, 10, and 12 and a moving average at lag 1 was found to be the best model fit. For the 50–64 year-old age group, an ARIMA (12, 0, and 0) model with autoregressive terms at lags 3, 10, and 12 was found to be the best model fit (Table 2). After the time series AR and MA terms were initially identified for each model, four nonstochastic parameters were added to each of the ARIMA models to estimate the impact of the guideline change. AR and MA terms were then reidentified with the models, including the nonstochastic parameters.

Table 2.

Parameter Estimates from Sensitivity Analysis 1, Interrupted Time Series ARIMA Models

| 40–49 year-old ARIMA model | 50–64 year-old ARIMA model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard error | T-value | p-value | Estimate | Standard error | T-value | p-value |

| B0, intercept | 39.9988 | 1.2253 | 32.64 | <0.0001 | 53.3962 | 1.113 | 47.98 | <0.0001 |

| MA(1) | 0.4593 | 0.4534 | 1.01 | 0.3139 | — | — | — | — |

| AR(1) | 0.6499 | 0.4069 | 1.6 | 0.1139 | — | — | — | — |

| AR(3) | 0.2796 | 0.1371 | 2.04 | 0.0444 | 0.2240 | 0.1137 | 1.97 | 0.052 |

| AR(10) | −0.3308 | 0.1113 | −2.97 | 0.0038 | −0.3907 | 0.1093 | −3.57 | 0.0006 |

| AR(12) | 0.9097 | 0.0705 | 12.91 | <0.0001 | 0.9247 | 0.0647 | 14.3 | <0.0001 |

| B1, time | 0.0050 | 0.0634 | 0.08 | 0.937 | 0.0252 | 0.0522 | 0.48 | 0.6299 |

| B2, intervention | −2.3931 | 1.4244 | −1.68 | 0.0966 | −0.8130 | 1.2443 | −0.65 | 0.5152 |

| B3, timeafterintervention | 0.0891 | 0.0843 | 1.06 | 0.2937 | 0.0477 | 0.0666 | 0.72 | 0.4759 |

| B4, pulseshift | −3.4759 | 1.4299 | −2.43 | 0.0171 | −5.2487 | 1.6273 | −3.23 | 0.0018 |

Time, change in trend across time; Intervention, after guideline change in level; Timeafterintervention, after guideline change in linear trend; Pulseshift, change in level of screening rates in the 2 months after guideline.

The model for the 40–49 year-old group was represented by

|

where  represents the estimated monthly screening rate, Time is a linear trend term (continuous variable starting at 1 and increasing by 1 for each month), Intervention is an intercept shift term (binary variable equal to 0 before and 1 after the guideline change (starting in January 2010)), TimeAfterIntervention is a postguideline linear trend term (continuous variable with a value equal to 0 before the guideline change and starting at 1 and increasing by 1 after the guideline implementation), and TwoMonthsAfter is a pulse term to capture any temporary rate change immediately after the guideline change (binary variable equal to 1 in the 2 months after the guideline change (January and February 2010) and equal to 0 in all other months).31,32 The

represents the estimated monthly screening rate, Time is a linear trend term (continuous variable starting at 1 and increasing by 1 for each month), Intervention is an intercept shift term (binary variable equal to 0 before and 1 after the guideline change (starting in January 2010)), TimeAfterIntervention is a postguideline linear trend term (continuous variable with a value equal to 0 before the guideline change and starting at 1 and increasing by 1 after the guideline implementation), and TwoMonthsAfter is a pulse term to capture any temporary rate change immediately after the guideline change (binary variable equal to 1 in the 2 months after the guideline change (January and February 2010) and equal to 0 in all other months).31,32 The  parameters represent the autoregressive terms and the

parameters represent the autoregressive terms and the  component represents the moving average parameter. This approach allows for analysis of the impact of the guideline change independent of any seasonal or overall trends in screening rates. The model for the 50–64 year olds used the same nonstochastic parameters, but used the autoregressive terms previously described.

component represents the moving average parameter. This approach allows for analysis of the impact of the guideline change independent of any seasonal or overall trends in screening rates. The model for the 50–64 year olds used the same nonstochastic parameters, but used the autoregressive terms previously described.

The addition of the TwoMonthsAfter pulse shift parameter was not included a priori. We initially used the Box-Jenkins approach to achieve stationary data, absent autocorrelation between the monthly rates, with the sole additions of a parameter to account for a shift in trend (TimeAfterIntervention) and a parameter to account for a shift in level (Intervention). After initial inspection, it was apparent that including a 2-month pulse parameter would improve the model fit.

A second sensitivity analysis accounted for the potential impact of changing demographic factors of the study population on the ARIMA estimates. Specifically, average age and the percent of women with the most common insurance type (i.e., Preferred Provider Organization [PPO]) were added as stochastic terms to the ARIMA analyses. Autoregressive and moving average terms were refit to produce the best fitting model using the stochastic covariates (Table 3).

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates from Sensitivity Analysis 2, Interrupted Time Series ARIMA Models with Demographic Covariates

| 40–49 year-old ARIMA model | 50–64 year-old ARIMA model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard error | T-value | p-value | Estimate | Standard error | T-value | p-value |

| B0, intercept | −438.50425 | 79.0346 | −5.55 | <0.0001 | −809.21 | 159.9385 | −5.06 | <0.0001 |

| AR(2) | 0.28674 | 0.1113 | 2.58 | 0.0117 | 0.23472 | 0.1114 | 2.11 | 0.038 |

| AR(3) | 0.43900 | 0.1064 | 4.13 | <0.0001 | 0.3499 | 0.1092 | 3.21 | 0.0019 |

| AR(10) | −0.38645 | 0.1068 | −3.62 | 0.0005 | −0.36615 | 0.1091 | −3.36 | 0.0012 |

| AR(12) | 0.74187 | 0.0901 | 8.24 | <0.0001 | 0.75365 | 0.0879 | 8.57 | <0.0001 |

| B1, time | −0.24930 | 0.10791 | −2.31 | 0.0233 | −0.31751 | 0.1175 | −2.7 | 0.0083 |

| B2, intervention | −3.18311 | 1.6268 | −1.96 | 0.0537 | −2.63915 | 2.1778 | −1.21 | 0.2289 |

| B3, timeafterintervention | 0.27036 | 0.1063 | 2.54 | 0.0128 | 0.27778 | 0.1153 | 2.41 | 0.0181 |

| B4, pulseshift | −3.10182 | 1.2241 | −2.53 | 0.0131 | −4.96309 | 1.6826 | −2.95 | 0.0041 |

| Mean Age | 9.80870 | 1.7398 | 5.64 | <0.0001 | 14.60742 | 2.8411 | 5.14 | <0.0001 |

| Percent PPO | 71.94610 | 26.7536 | 2.69 | 0.0086 | 70.13133 | 31.6626 | 2.21 | 0.0294 |

Time, change in trend across time; Intervention, after guideline change in level; Timeafterintervention, after guideline change in linear trend; Pulseshift, change in level of screening rates in the 2 months after guideline; PPO, preferred provider organization.

All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and significance was assumed to be p < 0.05.

Results

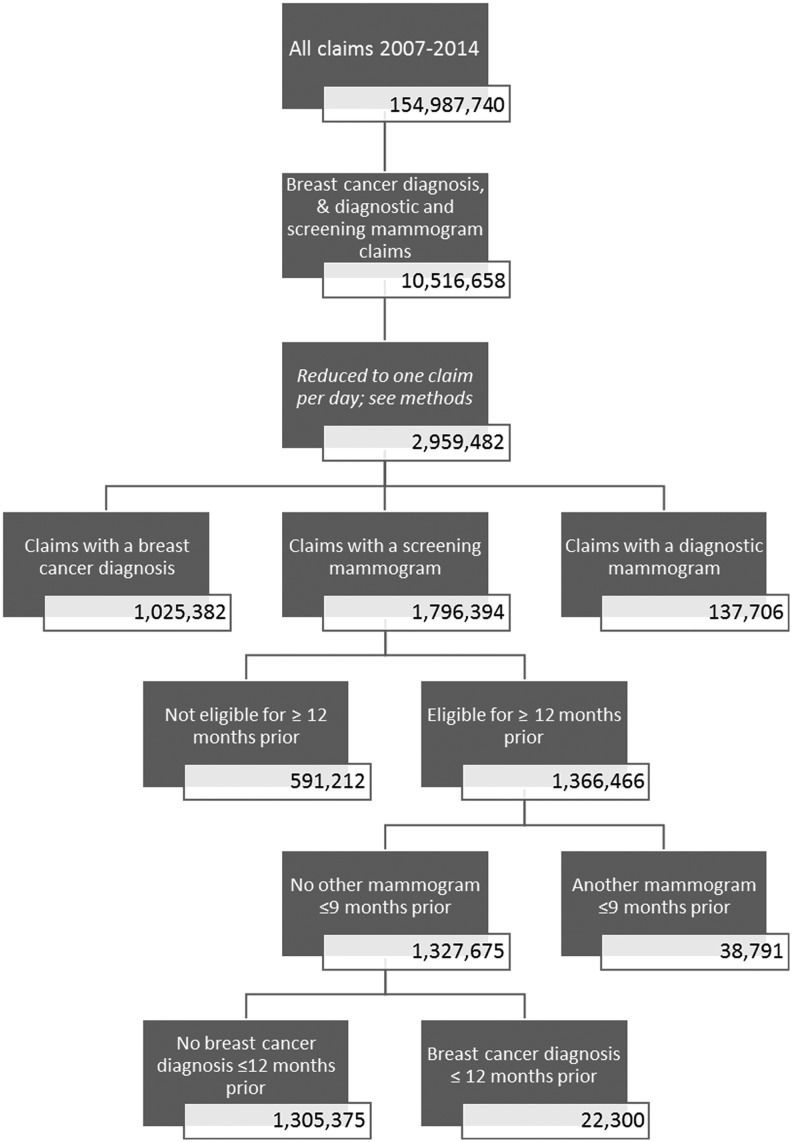

The study sample consisted of 1,436,077 women who were in the eligible age range and with at least 1 month of insurance coverage during the study period (Fig. 1). After applying monthly eligibility criteria, the final study sample included 493,347 women with at least 1 month of eligibility as 40–49 year olds and 658,052 women with at least 1 month of eligibility as 50–64 year olds. There were 1,305,375 total screening mammograms from 2007 to 2014 (Fig. 2). After excluding screens that were ineligible because of previous mammograpies within 9 months or previous breast cancer within 1 year, there were 367,524 screens among 40–49 year olds and 736,992 screens among 50–64 year olds.

FIG. 1.

Count of individuals at each stage of enrollment selection.

FIG. 2.

Count of claims at each stage of identifying screening mammograms.

The average age of the study sample in 2007 was 47.7 years (95% CI: 40.0–55.4). The average monthly screening rate was 40.4 (95% CI: 35.9–44.9) per 1,000 women aged 40–49 years and 54.8 (95% CI: 49.0–60.5) per 1,000 women aged 50–64 years.

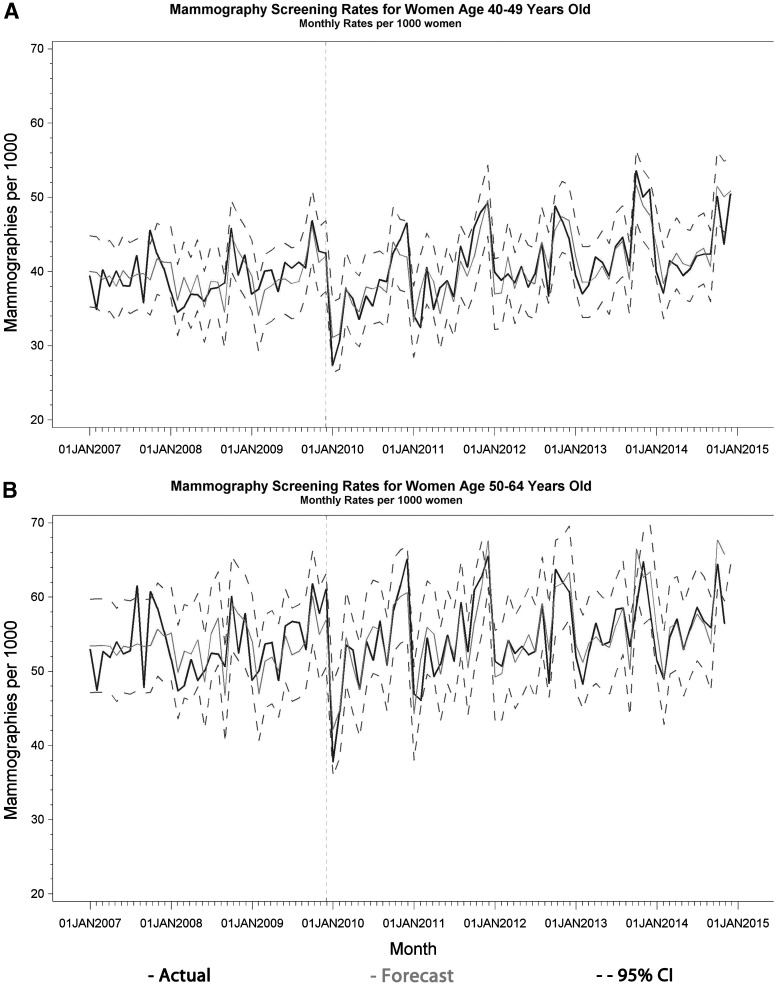

Figure 3 displays the forecasted time series estimates of monthly mammography rates for both age groups. The ARIMA forecast analysis revealed that only the 2 months immediately following the guideline change had a monthly screening rate outside of the 95% CI for the forecasted rates for the 40–49 year olds (Table 4 and Fig. 3A). For the 50–64 year olds, these 2 months in addition to February 2011 were the only months outside of the 95% CI after the guideline change (Table 4 and Fig. 3B). In those 2 months (January and February 2010), monthly screening rates per 1,000 women decreased by 4.8 (95% CI: −6.0 to −3.6) for the 40–49 year olds and by 6.1 (95% CI: −7.5 to −4.6) for the 50–64 year olds. This is an 11.8% and 11.2% reduction, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Base Case: forecast ARIMA time series plots of mammography screening rates per 1,000 women. (A) ARIMA (12,1,0) for women aged 40–49. (B) ARIMA (12,1,2) for women aged 50–64.

Table 4.

Months and Values Outside of Forecasted Confidence Intervals

| 40–49 year-old model | 50–64 year-old model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Observed | Lower 95% CI | CI minus observed | Observed | 95% Lower CI | CI minus observed |

| Jan 2010 | 27.40 | 34.90 | 7.50 | 47.09 | 37.81 | 9.28 |

| Feb 2010 | 30.61 | 35.87 | 5.26 | 51.44 | 44.62 | 6.82 |

| Feb 2011 | — | — | — | 49.90 | 46.09 | 3.81 |

Sensitivity analyses

Figure 4 displays the observed monthly mammography rates and the interrupted time series estimates, including all AR and MA terms and the pulse shift parameter (Sensitivity Analysis 1) for both age groups. Consistent with the base case forecasting model, there is no apparent trend in the screening rates other than a temporary 2-month decrease indicated by the significant pulseshift parameter (Table 2). Of the four nonstochastic time series segmentation parameters, only the pulseshift parameter was statistically significant in either age group.

FIG. 4.

Sensitivity Analysis 1: interrupted time series ARIMA Plots of mammography screening rates per 1,000 women. (A) ARIMA (12,0,1) for women aged 40–49. (B) ARIMA (12,0,0) for women aged 50–64.

The second sensitivity analysis, which added average age and the percent of women with a PPO insurance type to the ARIMA analyses, found a nonsignificant negative intercept shift related to the guideline change (intervention) and a significant positive slope postguideline change (timeafterintervention) (Table 3). The nonsignificant intercept shift term (intervention) indicates that there was no long-term impact of the intervention, while the positive significant slope term after the intervention (timeafterintervention) indicates that there was a slight increase in average annual mammography rates after the intervention in the second sensitivity analysis model.

This sensitivity analysis also revealed statistically significant positive relationships between monthly mammography rates and average age, as well as the percent PPO in both age groups, given the p-value of less than 0.05 for the positive parameter estimates for both mean age and percent PPO.

Discussion

This analysis of a nationally representative sample of commercially insured women aged 40–64 years provides insight into the long-term impact of the USPSTF guideline change on mammography screening rates. The ARIMA time series analysis revealed that the only statistically significant impact of the recommendation for either age group was a 2-month reduction following the guideline change. During these 2 months, the two age groups saw nearly equivalent relative declines in screening rates. It was anticipated that the younger age group would see a greater and more persistent decline because of the USPSTF recommendations that these individuals should no longer receive routine screenings.

Other studies evaluating the USPSTF mammography guideline change observed a similar short-term decline, but their conclusions differ regarding the long-term impact. Our study found a slight long-term increase in screening rates (Table 3, timeafterintervention), which is in the opposite direction expected after the guideline change. Because our analysis only evaluated changes in monthly mammography rates, rather than individual adherence to screening guidelines, further research should evaluate whether this increase resulted from more frequent mammography use than recommended by USPSTF.

The study that most closely aligns with our study utilizes similar sample population inclusion criteria and the same data source.12 This study had similar average screening rates for both the 40–49 year-old and 50–64 year-old age groups (34.2 and 42.9 per 1,000 women, respectively) and found that rates dropped in the 2 months following the change, but over the longer term, found that screening rates had a subtle increase over pre-existing downward trends.

Two studies that used data from the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) found a more persistent long-term decline in mammography rates than the 2-month drop found in our study. One of these studies found that the decline in mammography rates persisted through the 2010 collection of BRFSS data,13 and the second found that the decline persisted through 2012.33 There are several factors that may explain the inconsistency of these findings with ours. The information provided in the BRFSS survey allowed these studies to control for race, a variable that was not available in our study. A separate study that used patient-reported survey data found that mammography rates did not decline for non-White women age 50–74 or for White women age 40–49 or age 50–74; however, non-White women age 40–49 saw a 13% decrease from 2008 to 2013.14 The trends in screening rates in our study represent the average across all races with commercial insurance which may be less representative of non-Whites.

Another difference between the two studies13,33 that found a decline among all age groups across the study period may be due to different responses to the policy among uninsured, publicly insured, and privately insured women. Each of the studies based on the BRFSS controlled for “any insurance” and did not separate public insurance status (i.e., Medicare or Medicaid) from private insurance status. Our study includes data from privately insured individuals, who may have responded differently to the guideline change than the population of all insured individuals.

A plausible explanation for the short term temporary decrease in rates may be that the controversy surrounding the appropriateness of mammography screenings resulted in initial confusion among both the medical and lay-person communities.34,35 The ambiguous wording of the initial USPSTF recommendation made in November 2009 (i.e., that “The USPSTF recommends against routine screening mammography…”) may have contributed to the confusion among both providers and women. The USPSTF modified the language of the guideline the following month, in December 2009.34,36 After resolving this initial confusion, providers and patients appear to have resumed established routine practices.

USPSTF guidelines are often used as a basis for determining coverage decisions. The recommendations were highly criticized by some groups, particularly radiologists,37 leading to congressional action instructing the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to disregard the recommendations and expand required coverage of screening mammography to women aged 40 and older as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).38

Under the ACA, private payers must now cover screening mammography for women at least 40 years old; an exception exists for grandfathered private self-insured plans.38 The vast majority of individuals included in the LifeLink+ database are privately insured, many of whom are self-insured. The lack of a long-term decline in screening mammography rates for women aged 40–49 in this data indicates that payers largely continued paying for the service, despite the regulatory freedom to do otherwise. Likewise, women in their 40s largely continued to avail themselves of screenings at the same rate as those seen before the USPSTF guideline change, highlighting the guideline's lack of impact on individual patient decisions.

Some separate interesting observations from our time series revealed the unique periodicity of the data. As seen in Figures 3 and 4, the monthly screening rates peak around October of every year, which could be a result of breast cancer awareness month activities. The apparent impact of these activities suggests that an advertising campaign promoting the USPSTF screening guidelines may be effective in increasing adherence to the guidelines. In our second sensitivity analysis (Table 3), we observed that, as the share of PPO membership increases relative to other plan types (HMOs, self-directed consumer insurance), mammography rates also increase, suggesting that plan type may have an influence on mammography screening. We found that screening rates also increase as age increases (Table 3, MeanAge), as indicated by a positive coefficient for both age groups.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. To be included in the study population for a given month, women must have had 12 months of continuous commercial insurance before that month and be within the described age range. This may limit the generalizability of our findings since this excluded women who are less likely to maintain full employment. The algorithm we used to identify screening mammograms was derived using a Medicare population,26 and may have lower validity for a younger, commercially insured population. However, this algorithm has been previously used with populations of similar age and insurance status as our study.12,19

Although interrupted time-series analysis is considered one of the strongest quasi-experimental designs, it may not be able to capture the guideline's impact on rates because of confounding from other, contemporaneous factors (e.g., implementation of the ACA).39 Use of nonequivalent comparison services (e.g., pap smears)12 in other studies, however, indicate that these may have had little impact in this context. Also, it should be noted that the intercept shift (intervention) in the 40–49 year-old group approached significance in both sensitivity analyses (Tables 2 and 3), indicating that a more persistent reduction in mammography screening rates is possible. If there is a persistent decline, its effect, however, is likely small based on comparisons with the forecasted values.

We computed monthly rates of screening mammography, not individual adherence to the USPSTF guidelines (e.g., biennial for women age 50–64), to have a sufficient number of observations to estimate a time series model. Measuring individual adherence to the USPSTF recommendations may reveal a different response to the guideline change. In addition, the 3 years of data (36 months) used to forecast mammography rates after the guideline change are less than the suggested number of data points.29 Finally, we did not adjust for an exhaustive list of individual- or area-level covariates. Adjustment for these factors may reveal a different trend in mammography rates, such as increased response to the guideline change in states with a high concentration of health centers or mammography facilities.40,41

Conclusion

The USPSTF 2009 guideline change appears to have resulted in a temporary short-term modest decrease in mammography screening of approximately 10% that lasted only 2 months. There was no evidence that the guidelines affected screening mammography rates over the next 5 years after a 2-month temporary decrease. There was no consistent evidence that the guideline change affected the long-term rates of mammography in 40–49 year-old women for whom the guideline changed most profoundly. Future research should examine the possible overutilization and follow-up costs, outlined in the USPSTF guideline, associated with routine screening of younger, lower risk women.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences College of Pharmacy and College of Public Health classmates for feedback during this study (CB & AN). Acquisition of the data was supported by the UAMS Translational Research Institute (TRI), grant UL1TR000039 through the NIH National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:52–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States cancer statistics: 1999–2012 incidence and mortality web-based report. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute 2015. Available at: https://nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/index.aspx Accessed April1, 2016

- 3.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:117–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1784–1792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabar L, Gad A, Holmberg L, et al. Reduction in mortality from breast cancer after mass screening with mammography: Randomised trial from the breast cancer screening working group of the Swedish national board of health and welfare. Lancet 1985;325:829–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1998–2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: An update for the US preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:727–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolf SH. The 2009 breast cancer screening recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2010;303:162–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jørgensen KJ, Keen JD, Gøtzsche PC. Is mammographic screening justifiable considering its substantial overdiagnosis rate and minor effect on mortality? Radiology 2011;260:621–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodersen J, Siersma VD. Long-term psychosocial consequences of false-positive screening mammography. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:106–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:716–726, W-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang AT, Fan J, Van Houten HK, et al. Impact of the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines on screening mammography rates on women in their 40 s. PLoS One 2014;9:e91399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Block LD, Jarlenski MP, Wu AW, Bennett WL. Mammography use among women ages 40–49 after the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1447–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzales FA, Taplin SH, Yu M, Breen N, Cronin KA. Receipt of mammography recommendations among white and non-white women before and after the 2009 United States Preventive Services Task Force recommendation change. Cancer Causes Control 2016;27:977–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirth JM, Kuo YF, Lin YL, Berenson AB. Regional variation in mammography use among insured women 40–49 years old: Impact of a USPSTF guideline change. J Health Sci (El Monte) 2015;3:174–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard DH, Adams EK. Mammography rates after the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force breast cancer screening recommendation. Prev Med 2012;55:485–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang M, Hughes DR, Duszak R. Screening mammography rates in the medicare population before and after the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force guideline change: An interrupted time series analysis. Womens Health Issues 2015;25:239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pace LE, He Y, Keating NL. Trends in mammography screening rates after publication of the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. Cancer 2013;119:2518–2523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wharam JF, Landon B, Zhang F, Xu X, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Mammography rates 3 years after the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines changes. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1067–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill A, Bigby J. Databases to track use of preventive services after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. 2015. Available at: www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/databases-to-track-use-of-preventive-services-after-implementation-of-the-affordable-care-act-ib Accessed April1, 2016

- 21.Kappelman MD, Rifas–Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:1424–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stempel D, Mauskopf J, McLaughlin T, Yazdani C, Stanford R. Comparison of asthma costs in patients starting fluticasone propionate compared to patients starting montelukast. Respir Med 2001;95:227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller M, Pate V, Swanson SA, Azrael D, White A, Stürmer T. Antidepressant class, age, and the risk of deliberate self-harm: A propensity score matched cohort study of SSRI and SNRI users in the USA. CNS drugs 2014;28:79–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blustein J. Medicare coverage, supplemental insurance, and the use of mammography by older women. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1138–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman JL, Klabunde CN, Schussler N, Warren JL, Virnig BA, Cooper GS. Measuring breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screening with medicare claims data. Med Care 2002:IV36–IV42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenton JJ, Zhu W, Balch S, Smith-Bindman R, Fishman P, Hubbard RA. Distinguishing screening from diagnostic mammograms using Medicare claims data. Med Care 2014;52:e44–e51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith-Bindman R, Quale C, Chu PW, Rosenberg R, Kerlikowske K. Can Medicare billing claims data be used to assess mammography utilization among women ages 65 and older? Med Care 2006;44:463–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Box GE, Jenkins GM, Reinsel GC, Ljung GM. Time series analysis: Forecasting and control. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biglan A, Ary D, Wagenaar AC. The value of interrupted time-series experiments for community intervention research. Prev Sci 2000;1:31–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holder HD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of the elimination of a state monopoly on distilled spirits' retail sales: A time‐series analysis of Iowa. Br J Addict 1990;85:1615–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Box GE, Tiao GC. Intervention analysis with applications to economic and environmental problems. J Am Stat Assoc 1975;70:70–79 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo JJ, Curkendall S, Jones JK, Fife D, Goehring E, She D. Impact of cisapride label changes on codispensing of contraindicated medications. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2003;12:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gray N, Picone G. The effect of the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force breast cancer screening recommendations on mammography rates. Health Serv Res 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Squiers LB, Holden DJ, Dolina SE, Kim AE, Bann CM, Renaud JM. The public's response to the US Preventive Services Task Force's 2009 recommendations on mammography screening. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutten LJF, Ebbert JO, Jacobson DJ, et al. Changes in US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations: Effect on mammography screening in Olmsted county, MN 2004–2013. Prev Med 2014;69:235–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Archived: Breast cancer: Screening original release date: November 2009. Updated 2016. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breast-cancer-screening Accessed August5, 2017

- 37.American College of Radiology. Position statement. USPSTF mammography recommendations will result in countless unnecessary breast cancer deaths each year. Updated 2009. Available at: www.acr.org/About-Us/Media-Center/Position-Statements/Position-Statements-Folder/USPSTF-Mammography-Recommendations-Will-Result-in-Countless-Unnecessary-Breast-Cancer-Deaths Accessed August15, 2016

- 38.Wilensky G. The mammography guidelines and evidence-based medicine. Health Affairs Blog.2010. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2010/01/12/the-mammograpy-guidelines-and-evidence-based-medicine Accessed August15, 2016

- 39.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross‐Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coughlin SS, Leadbetter S, Richards T, Sabatino SA. Contextual analysis of breast and cervical cancer screening and factors associated with health care access among united states women, 2002. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:260–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eberth JM, Eschbach K, Morris JS, Nguyen HT, Hossain MM, Elting LS. Geographic disparities in mammography capacity in the south: A longitudinal assessment of supply and demand. Health Serv Res 2014;49:171–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]