Abstract

Considering there are no treatments for progressive forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), a comprehensive understanding of the role of neurodegeneration in the pathogenesis of MS should lead to novel therapeutic strategies to treat it. Many studies have implicated viral triggers as a cause of MS, yet no single virus has been exclusively shown to cause MS. Given this, human and animal viral models of MS are used to study its pathogenesis. One example is human T-lymphotropic virus type 1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP). Importantly, HAM/TSP is similar clinically, pathologically, and immunologically to progressive MS. Interestingly, both MS and HAM/TSP patients were found to make antibodies to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A1, an RNA-binding protein overexpressed in neurons. Anti-hnRNP A1 antibodies reduced neuronal firing and caused neurodegeneration in neuronal cell lines, suggesting the autoantibodies are pathogenic. Further, microarray analyses of neurons exposed to anti-hnRNP A1 antibodies revealed novel pathways of neurodegeneration related to alterations of RNA levels of the spinal paraplegia genes (SPGs). Mutations in SPGs cause hereditary spastic paraparesis, genetic disorders clinically indistinguishable from progressive MS and HAM/TSP. Thus, there is a strong association between involvement of SPGs in neurodegeneration and the clinical phenotype of progressive MS and HAM/TSP patients, who commonly develop spastic paraparesis. Taken together, these data begin to clarify mechanisms of neurodegeneration related to the clinical presentation of patients with chronic immune-mediated neurological disease of the central nervous system, which will give insights into the design of novel therapies to treat these neurological diseases.

Keywords: human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), multiple sclerosis, neurodegeneration, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNP A1), autoimmunity, spastic paraparesis, RNA-binding protein

Clinical phenotype of progressive neurodegenerative diseases

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common human demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS), affecting as much as 0.2% of the population in high-prevalence areas.1 MS most frequently affects middle-aged people, and there are an estimated 2 million cases worldwide,1 of which 400,000 are in the United States.2 Initially, two-thirds of patients develop relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), in which neurological symptoms occur followed by complete or incomplete recovery.1,3,4 Over time, a significant proportion (up to 90% within 25 years2) of these patients may develop neurological deterioration independent of relapses and thus develop “secondary progressive MS” (SPMS).1,3,4 Approximately 15% of people develop primary progressive MS (PPMS), in which neurological symptoms progress over time without relapses.1,3,4 Thus, the majority of patients develop progressive forms of MS during their lifetime.1,2,4 Progression in individual patients is highly variable, and may be related to whether patients have plaques in the brain, spinal cord, or both.5,6 Common symptoms of progressive forms of MS include spastic paraparesis, sensory dysfunction including neuropathic pain, and urinary disturbance.7

Despite decades of research, the etiology of MS remains elusive. Evidence indicates that exposure to an environmental agent (such as a virus) in a genetically susceptible person results in a series of immunological events that lead to neurological damage. Importantly, a number of hypotheses have attempted to link exposure to environmental agents with stimulation of the immune response, which in turn leads to CNS damage. One example is molecular mimicry. The challenge in studying molecular mimicry in MS is that an infectious agent has not unequivocally been shown to cause it, although data suggest Chlamydia pneumoniae, human herpes virus 6, or Epstein–Barr virus may play a role.8–10 To address this, we use human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) as a model to study molecular mimicry in autoimmune diseases of the CNS.11–15 HAM/TSP is caused by HTLV-1, which allows for the direct comparison of the infecting agent with host antigens.16–24 Importantly, HAM/TSP patients are similar clinically, pathologically, and immunologically to people with progressive MS. In fact, many HAM/TSP patients were initially diagnosed with PPMS.11–13,19,20,25,26

In addition to HAM/TSP, progressive forms of MS are clinically and pathologically similar to the hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) (Table 1).7,27,28 The HSPs are a clinically and genetically diverse group of diseases, which like progressive MS and HAM/TSP are characterized by spastic paraparesis, urinary symptoms, and posterior column dysfunction. HSPs are caused by mutations in the spinal paraplegia genes (SPGs). The predominant manifestation of “pure or uncomplicated” HSP is spastic paraparesis. Patients with “complicated” HSPs develop spastic paraparesis concurrent with other neurologic abnormalities, such as ataxia, optic atrophy, peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, and dementia.27,28 MS and HAM/TSP patients also exhibit some of these symptoms.21–24 Pathologically, progressive MS, HAM/TSP, and HSP are characterized by damage to and neurodegeneration of the long tracts of the CNS, including the corticospinal tracts and posterior column/medial lemniscal sensory system (Table 1).7,11,27–33

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological features of progressive MS, HAM/TSP, and HSP

| Clinical |

| • Spastic paraparesis |

| • Sensory dysfunction |

| • Urinary disturbance |

| Pathological |

| • Axonal damage/neurodegeneration |

| ○ Corticospinal motor system |

| ○ Posterior column/medial lemniscal sensory system |

| • Spinal cord atrophy |

| Genetic contribution |

| • MS: HLA DRB1*1501/DQB1*602 |

| • HAM/TSP: HLA DRB1*0101 |

| • HSP: autosomal dominant/recessive, X-linked |

| Etiology |

| • MS: autoimmune (viruses considered) |

| • HAM/TSP: HTLV-1 infection associated with autoimmunity |

| • HSP: mutations of SPGs |

Abbreviations: MS, multiple sclerosis; HAM/TSP, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis; HSP, hereditary spastic paraparesis; SPGs, spinal paraplegia genes; HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

Contribution of neurodegeneration to the pathogenesis of immune-mediated neurological diseases

Over the past several years, there has been a major shift in thinking about the pathogenesis of progressive forms of MS.1,34–47 Prevailing hypotheses suggested that progressive disease and disability were related to the location and volume of MS white-matter plaques (the “plaque-centric” viewpoint), and that neurodegeneration was present only in the latter stages of progressive MS. There is now evidence that neurodegeneration is present in all stages of the disease.34,42,48,49 In addition, neurodegeneration in progressive forms of MS is not related to white-matter plaques or their location, but rather correlates with gray matter and cortical pathology.2,34,35,48,50–55 Brain magnetic resonance imaging data support the concept that gray-matter disease and neurodegeneration is a more sensitive marker of progression than white-matter disease.53–55 For example, gray-matter atrophy is increased when comparing SPMS patients to controls.53 In addition, there was significantly greater gray-matter than white-matter atrophy when comparing SPMS to other forms of MS, and it was gray-matter atrophy that correlated with disability.54 Pathologically, cortical demyelination has been shown to contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of MS.2,34,35,48,50–55 Inflammatory cells and neurodegeneration are present in all stages of MS. However, the type and quantity of inflammatory cells and the extent of neurodegeneration are related to MS subtype. For example, in early forms of MS (acute and RRMS), T cells and B cells predominate and correlate with demyelination (plaque location) and neuronal injury, as detected by amyloid precursor protein (APP) staining.36,48 In progressive forms of the disease, the inflammatory response is more diffuse (involving CNS parenchyma and meninges) and immunoglobulin G (IgG)-positive plasma cells predominate.48 Importantly, B-cell follicle-like structures present in the meninges in SPMS are associated with cortical pathology such as subpial cortical demyelination and atrophy.56,57 Also, there is neuronal loss and apoptosis within the motor cortex, particularly in motor pyramidal neurons in layers III and V, which contain the cells of origin of the corticospinal tract.57 This is particularly relevant, because in progressive MS patients spastic paraparesis predominates and there is a strong clinical correlation between axonal damage and neurological disability related to the long tracts of the CNS.1 For example, analysis of the corticospinal tract and posterior columns in the spinal cord of MS patients showed a significant reduction of nerve-fiber density independent of cerebral plaque location, which correlated strongly with progression.32,58–61

The neuropathology of the spinal cord in HAM/TSP closely resembles that seen in progressive forms of MS, and forms the basis for hypotheses related to the pathogenesis of viral-induced, immune-mediated neurological disease. Like MS, the corticospinal tract and posterior columns are preferentially damaged and demonstrate axonal dystrophy and demyelination.20,30,33,62,63 In addition, there is increased APP expression indicative of neurodegeneration within the corticospinal tract.29 In both HAM/TSP and MS, magnetic resonance images show spinal cord atrophy.64,65 There is blood–brain barrier breakdown and infiltration of the CNS with inflammatory cells, which localize predominantly to the thoracic spinal cord, where a majority of cells concentrate in the lateral (inclusive of the corticospinal tract) and posterior columns.20,30,33,62,63 These areas also correlate with relatively low blood flow within the spinal cord parenchyma.33 CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes as well as B cells and natural killer cells have been localized to the spinal cord, and their ratios are related to disease chronicity.19,66 Some CD8+ cells costained with T cells restricted intracellular antigen 1, a marker of cytotoxic T cells.33,66 Importantly, both HTLV-1 tax provirus and RNA were localized to infiltrating T cells in the spinal cord.67,68 There is little evidence of direct infection of neural elements with HTLV-1. Thus, data indicate that immune-mediated mechanisms contribute to the pathogenesis of HAM/TSP.12,13,20,22,24,69–73 For example, HAM/TSP patients make immune responses to a number of viral targets including HTLV-1 tax, env, and gag that separates them from control populations.74–77 Immunologically, HAM/TSP patients develop CD8+, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-2-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) specific for tax and CD4+ responses to both tax and env that are thought to contribute to disease.74,75,78 In contrast, other studies suggest that tax-specific CTLs are protective rather than pathogenic.74,79 In addition, CTLs to the newly discovered HTLV-1 basic leucine zipper factor appear to have a protective influence for the development of HAM/TSP.80 Interestingly, CD8+ lymphocytes also play an important role in the pathogenesis of MS.81 For example, MS patients have elevated cytotoxic responses by interleukin-15-exposed CD8+ lymphocytes and cytotoxic C8+ lymphocytes are present in MS plaques.81,82 In HAM/TSP, other inflammatory cells might also contribute to its pathogenesis including natural killer cells and interferon-γ-secreting Foxp3-CD4+CD25+CCR4+ T cells.23,83,84 Interestingly, the HLA class 2 gene HLA-DRB1*0101 increased HTLV-1 viral load (blood and spinal fluid) and elevated HTLV-1 antibody titers were found to increase the risk of HAM/TSP.20,74,79,85–87 Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon-γ are also associated with HAM/TSP, as are interferon-stimulated genes such as STAT1, STAT2, TAP1, and CXCL10.22,88,89 Taken together, these data are closely related pathologically and immunologically to MS, and suggest that immune-mediated mechanisms contribute to the pathogenesis of both MS and HAM/TSP.

Mechanisms of neurodegeneration in MS are similar to other neurodegenerative diseases

The mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration in MS are an area of intense investigation and remain an open question. There is evidence that neurodegeneration might result from lack of trophic support from myelin,41 abnormal ion- and sodium-channel expression on axons,1,34,90 calcium accumulation in damaged axons, or Wallerian degeneration.34,91 Inflammatory cytokines may also play a role.34 Several studies have shown that mitochondrial injury and associated oxidative damage, production of reactive oxygen species, and induction of apoptosis contribute to axonal injury.42,92–94 Other studies implicate increased energy demands of demyelinating axons and the relative reduction of axonal adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, which results in a state of “virtual hypoxia.”91,95

Several studies have demonstrated axonal changes in association with increased APP levels.42,96 Importantly, APP accumulation develops in the setting of abnormal fast axonal transport and has been shown not only to accumulate in damaged axons in MS brains48,97 but is also an early marker of axonopathy related to impaired axonal transport in Alzheimer’s disease.98 Notably, increased APP expression is also present within the corticospinal tracts of HAM/TSP patients.29,33 Abnormal axonal transport results in neurodegeneration in a number of neurodegenerative diseases.99 This is particularly evident in the HSPs. For example, some HSP genes, such as spinal paraplegia gene 4 (SPG4 – spastin), SPG7 (paraplegin), and SPG20 (spartin), have all been shown to contribute to axonal transport.27,28,99–102

In addition to these mechanisms, recent studies have implicated RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and their function in RNA metabolism (ie, transport, stability, translation) as major contributors to abnormal neuronal function and neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, spinal muscle atrophy, and dementia.103,104 For example, the RBP TAR DNA-binding protein 43 has been identified as a major contributor to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia.105,106 Also, RNA metabolism related to fragile X mental retardation protein appears to contribute to the pathogenesis of fragile X syndrome and fragile X syndrome-associated tremor/ataxia.103 Further, patients with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes develop antibodies to RBPs, such as Hu and Nova.103,107,108 Taken together, these data show that neurodegeneration in MS involves mechanisms that are also present in other neurodegenerative diseases.

Antibodies as contributors to neurodegeneration and the pathogenesis of MS

In addition to T cells, recent studies have emphasized the role of humoral autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of MS.47,109,110 Clinically, intrathecal IgG and oligoclonal bands are a hallmark of MS.109,110 Some types of MS show Ig and complement deposition in MS lesions, and some MS patients exhibit a therapeutic response to plasma exchange or B-cell depletion with anti-CD20 antibodies.111–117

The humoral immune response may be particularly important when studying neurodegeneration.1,4,37–41,118 For example, patients with progressive disease are more likely to have B-cell follicle-like structures in the cerebral meninges.56,57,110,117 IgG-containing plasma cells are found in the meninges and throughout the brain in MS patients, and persist in progressive forms of MS when T cells and B cells diminish to control levels.48,117 Importantly, studies also show that antibodies to neurons and axons contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration in MS.119,120 In one study, MS patients were found to make antibodies to neurofascin.119,120 The autoantibodies reacted to both neurofascin 186 (a neuronal protein located on axons at the nodes of Ranvier) and neurofascin 155, an oligodendrocyte protein.119,120 Application of these antibodies to hippocampal slice cultures inhibited axonal conduction.120 Following induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T cells, the addition of antineurofascin antibodies augmented disease.120 The antibodies bound to the nodes of Ranvier, resulting in complement deposition and axonal injury. Taken together, these data indicate antibodies that target neuronal antigens are pathogenic.119,120

These data suggest that antibodies to CNS targets other than myelin, such as neurons and axons, may make major contributions to the pathogenesis of MS. For example, studies in MS patients revealed that there were elevated antibodies to the “axolemma-enriched fraction,” neurofilament, and gangliosides.121–123 Also, Owens et al109 tested recombinant monoclonal antibodies derived from the light-variable region sequences of plasma and B-cell clones isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of MS patients for immunoreactivity to myelin antigens. Remarkably, none of the recombinant antibodies reacted with myelin basic protein, proteolipid protein, or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein.109 These data suggest the myelin compartment may not always be a target for a pathogenic humoral response in MS patients and that other autoantigens might be important. For example, a recent study showed that autoantibodies to the potassium channel KIR4.1, a glial protein, might contribute to the pathogenesis of MS.124,125

A potential role for antibodies to the RBP hnRNP A1 in the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration in MS and HAM/TSP

Data generated in our lab also indicate that antibodies to the nonmyelin compartment, specifically neurons, may contribute to the pathogenesis of MS and HAM/TSP.11–14,126–129 Initially, using neuronal proteins purified from human brain, IgG isolated from HAM/TSP patients was found to immunoreact with a 33 kDa protein by Western blot.126 Subsequently, the protein was identified as heterogeneous nuclear ribonuclear protein A1 (hnRNP A1).14 hnRNP A1 is an RBP that has multiple functions, including mRNA nucleocytoplasmic transport, metabolism, and translation.130,131 Importantly, HAM/TSP IgG reacted specifically with neurons, but not with proteins isolated from systemic organs.14,132 Further, HAM/TSP IgG reacted preferentially with neurons isolated from human precentral gyrus, including Betz cells, the neuronal cells of origin of the corticospinal tract.14 In HAM/TSP brain, in situ IgG localized to the corticospinal tract, pyramidal neurons of the precentral gyrus, and the posterior column/medial lemniscal sensory system, areas that are commonly damaged in HAM/TSP.30 In addition, anti-hnRNP A1 antibodies decreased neuronal firing in ex vivo patch-clamp experiments of rat brain slices.14,133 The human epitope of hnRNP A1 recognized by HAM/TSP IgG was mapped to an amino acid sequence (AA 293-GQYFAKPRNQGG-304) contained within M9 (the nuclear transport sequence of hnRNP A1), which is required for its nucleocytoplasmic transport (Figure 1).12,127 Importantly, an HTLV-1 tax monoclonal antibody showed cross-reactivity with human neurons and hnRNP A1 indicative of molecular mimicry between the two proteins.12–14,132 The cross-reactivity between HTLV-1 tax monoclonal antibodies with a 33 kDa brain-derived protein was replicated independently.134 Taken together, these data suggest that HAM/TSP patients develop a highly specific antibody response to neurons that is biologically active and potentially contributory to the pathogenesis of this immune-mediated neurologic disease.12,13

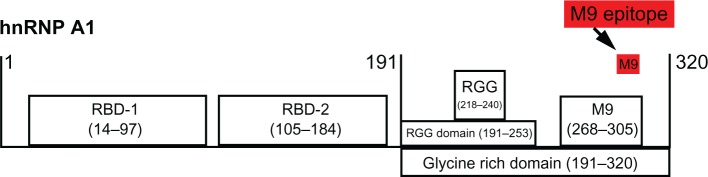

Figure 1.

Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) and multiple sclerosis (MS) immunoglobulin G (IgG) react with the same epitope in M9. Schematic of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A1 shows the RNA-binding domains (RBDs), the RGG domain, and M9. Overlapping protein-fragment experiments showed HAM/TSP and MS IgG reacted with an epitope (amino acids [AA] 293-GQYFAKPRNQGG-304, red box), which is contained within the M9 sequence (AA 268–305).11,127

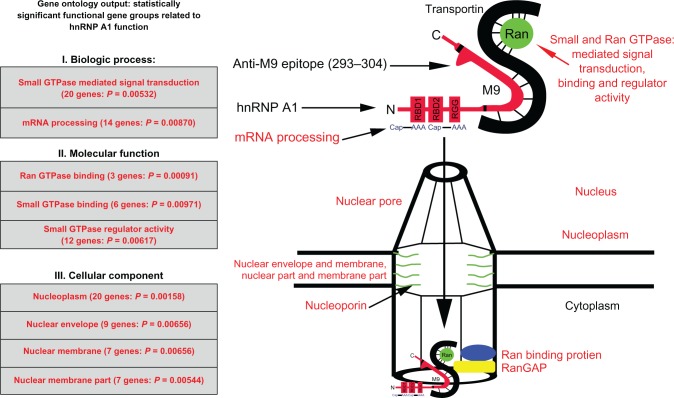

Because of similarities between the chronic, progressive nature and pathology of HAM/TSP and progressive forms of MS, we hypothesized that MS patients would also develop antibodies to hnRNP A1. This was found to be the case.11 Specifically, IgG isolated from the serum of MS patients immunoreacted with neurons but not systemic organs. In addition, MS IgG immunoreacted with the identical M9 epitope as the HAM/TSP patients (Figure 1). The sera of all 37 MS patients examined were positive for the M9 epitope. In contrast, normal controls and patients with Alzheimer’s disease (a control for neurodegenerative disease) showed no immunoreactivity. IgG from the CSF of an MS patient also immunoreacted with the M9 epitope.11 Of note, the study group included 49% RRMS, 27% SPMS, and 24% PPMS. Greater than 89% of patients had clinical evidence of corticospinal dysfunction.11 Other groups have confirmed that IgG isolated from the CSF of HAM/TSP and MS patients immunoreacts with hnRNP A1.135,136 We then hypothesized that the anti-hnRNP A1-M9 antibodies might contribute to neurodegeneration. To test this hypothesis, we transfected neurons with anti-M9 and control antibodies and examined them for signs of neurodegeneration and changes in gene expression using microarray.11,137 In contrast to control neurons, neurons containing the anti-M9 antibodies showed evidence of neurodegeneration, including positive staining with Fluoro Jade C (a fluorescent marker for degenerating neurons)138 and loss of neuronal processes.11 Microarray analyses of total RNA extracted from the cells showed that 866 transcripts were significantly altered by the M9-specific antibodies compared to controls. We investigated the functional significance of the gene-expression changes associated with anti-hnRNP A1 M9 antibody transfection of neurons using a dual bioinformatics approach.11 First, the 866 genes that were significantly altered by the anti-M9 antibodies were functionally classified by Gene Ontology annotation using the Gene Ontology Tree Machine. Remarkably, the anti-M9 antibodies affected almost all aspects of hnRNP A1’s role in nucleocytoplasmic transport and mRNA processing (Figure 2).11,139–142 The second bioinformatics approach we utilized relied on a text-mining system that queries Medline abstracts called GeneIndexer (Computable Genomix, Memphis, TN).143 We used GeneIndexer to identify genes that correlate with the neural systems affected and the clinical symptoms present in progressive MS and HAM/TSP patients. By querying the identical 866 gene set with the clinical terms paraplegia, spastic, weakness, motor, and sensory and comparing them to nonspecific search terms, GeneIndexer identified networks of genes that correlated strongly with neurodegeneration of the neural systems damaged, and the clinical phenotype expressed, by patients with progressive MS and HAM/TSP (Table 2, column 1). Most notably, the SPGs were involved. Following this output, we manually reviewed the manuscripts (identified by GeneIndexer, which were derived from Medline abstracts) related to each of these genes, and categorized them according to their primary functions (unpublished observation) (Table 2). Importantly, these changes in gene expression in neuronal cell lines were confirmed in neurons isolated from the brains of HAM/TSP and progressive MS patients, suggesting the changes found in vitro are clinically and pathologically relevant.11

Figure 2.

Genes identified by Gene Ontology are directly related to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A1 function. The gene categories and some individual genes affected by the anti-M9 antibodies are shown in red type. The complete M9 sequence (amino acids [AA] 268–305) is elongated for emphasis and bordered by the black lines within hnRNP A1. Transportin binds the M9 region at AA 263–289. AA 293–304, which are recognized by the multiple sclerosis and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis immunoglobulin G anti-M9 immune response, are not bound to transportin, and thus are available for antibody binding.11

Abbreviation: GTP, guanosine triphosphate.

Table 2.

Gene clusters (color coded) identified by a text-mining database using clinical search terms following anti-hnRNP A1-M9 antibody transfection into neurons (column 1, color coded) and their primary functions (columns 2–7)

| Name | Neuronal Transport | Mitochondria | Ubiquitin Proteosome System/Autophagy | Endosome Lysosome Peroxisome | Myelination | Axonal Integrity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spg 4 | ||||||

| spg 7 | ||||||

| spg 20 | ||||||

| atxn 3 | ||||||

| slc6a8 | ||||||

| pnma1 | ||||||

| usp14 | ||||||

| alms1 | ||||||

| creld1 | ||||||

| dym | ||||||

| surf1 | ||||||

| wbscr20c | ||||||

| citrin | ||||||

| ulk2 | ||||||

| mig12 | ||||||

| sem 4f | ||||||

| abcd1 | ||||||

| ah1 | ||||||

| arsd | ||||||

| atp11a | ||||||

| dgcr6 | ||||||

| fam13a1 | ||||||

| pom121c | ||||||

| 441253 | ||||||

| mid2 | ||||||

| psap | ||||||

| ofd1 | ||||||

| psen1 | ||||||

| psen2 | ||||||

| sqstm1 | ||||||

| cutl2 | ||||||

| etv1 | ||||||

| kif5C | ||||||

| ift20 | ||||||

| myt1l | ||||||

| neurgrin | ||||||

| nrg1 | ||||||

| ift88 |

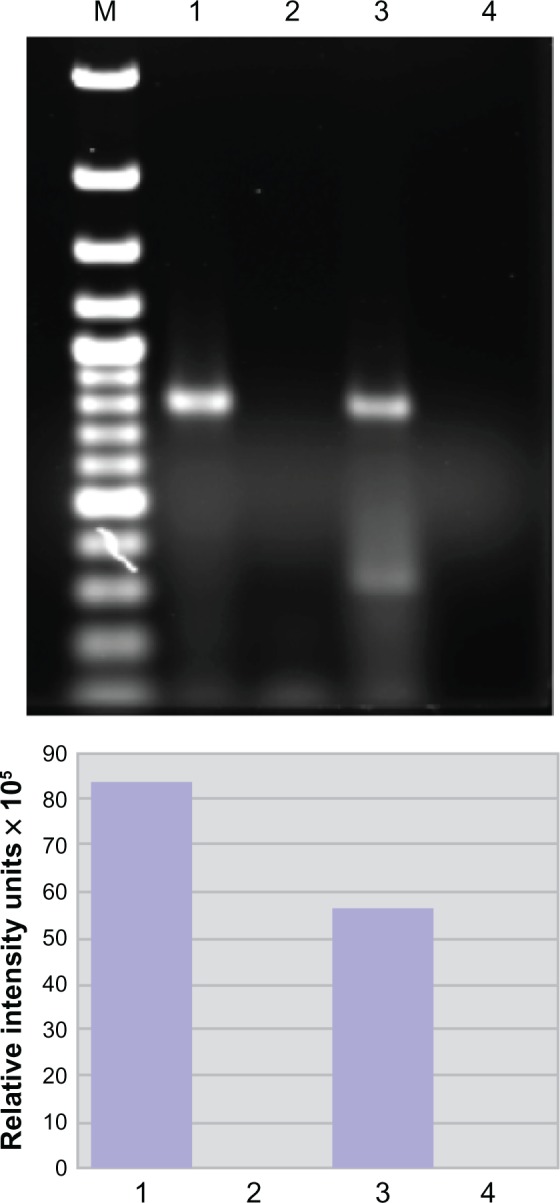

These data suggest a strong association might exist between hnRNP A1 and the SPGs. To prove such an association exists, we tested for molecular interactions between hnRNP A1 and spastin (SPG4). Following immunoprecipitation of neuronal lysates with anti-hnRNP A1 antibodies, we found that spastin protein was bound to hnRNP A1.11 This interaction was confirmed by immunohistochemistry, which revealed that spastin and hnRNP A1 colocalized within the nuclei of neurons.11 In separate experiments (Figure 3), we performed immunoprecipitation of neuronal lysates using hnRNP A1 antibodies, and examined the resulting complex for the presence of spastin mRNA. Following immunoprecipitation with anti-hnRNP A1 antibodies, there was enrichment of the spastin mRNA signal indicative of the binding of spastin mRNA to hnRNP A1 (unpublished observation) (Figure 3). In contrast, there was no signal following immunoprecipitation with a nonspecific antibody, confirming the specificity of spastin mRNA binding to hnRNP A1. These experiments confirm a biological interaction between the anti-M9 autoimmune response and neurodegeneration, as suggested by the bioinformatics analyses.11

Figure 3.

Spastin mRNA is bound to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A1 in neuronal cells. Upper panel: agarose gel. Compared to the neuronal lysate without immunoprecipitation or input (lane 3), there is an enriched spastin mRNA signal following immunoprecipitation with anti-hnRNP A1 mouse monoclonal antibodies (lane 1). In contrast, spastin mRNA was not isolated following immunoprecipitation with a nonspecific control antibody – mouse IgG (lane 2). Lane 4 used spastin primers without lysate (control for DNA contamination). Lower panel: the image was analyzed using ImageQuant software, which provided relative fluorescent intensity of the bands.

A link between autoimmunity and mechanisms of neurodegeneration

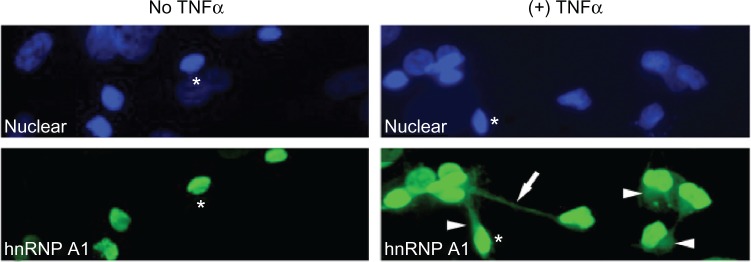

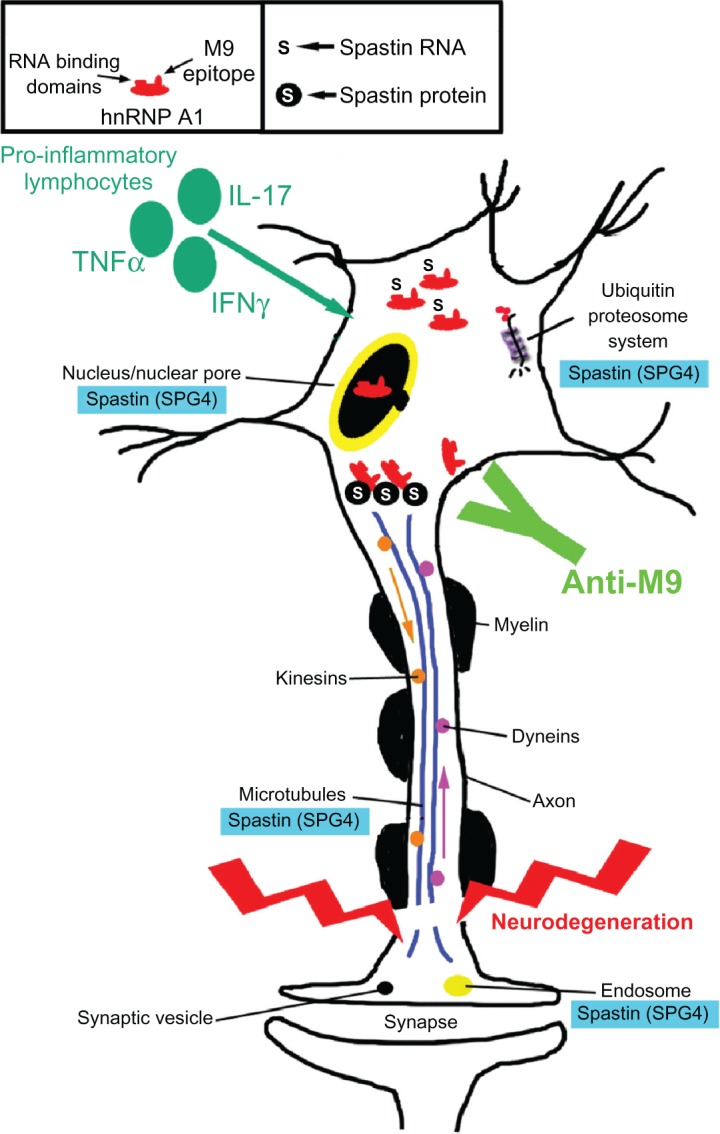

In summary, HAM/TSP and MS patients make antibodies to an epitope contained within the M9 region of hnRNP A1, an RBP that plays a critical role in RNA metabolism.11,130,131 Alterations in RBP function are associated with neurodegeneration.103 Anti-M9 antibodies caused neurodegeneration, loss of neuronal processes, and altered genes related to hnRNP A1 function and mechanisms of neurodegeneration associated with the clinical phenotype of HAM/TSP and progressive MS patients.11 Thus, a link between autoimmunity, clinical phenotype, and neurodegeneration has been identified. M9 is the nuclear export sequence and nuclear localization sequence of hnRNP A1, which is required for the “nonclassical” (transportin-mediated) pathway of nucleocytoplasmic transport.14,127,141,144 This is of particular interest considering that importins and exportins, which are required for “classical” (β-importin-mediated) nucleocytoplasmic transport, play a crucial role in nerve injury,145–148 and recently were shown to contribute to neurodegeneration in MS.148,149 Specifically, in neurons exposed to TNF-α, the transcription factor histone deacetylase 1 was transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm utilizing the β-importin-mediated nucleocytoplasmic transport system, which resulted in neurodegeneration in a model of MS.148 Similar findings were observed in experiments involving the transport of hnRNP A1 (unpublished observation) (Figure 4). Interestingly, spastin contains several nuclear export sequences and nuclear localization sequences, and thus is involved in classical (β-importin-mediated) nucleocytoplasmic transport.150 Our data indicate a molecular interaction exists between spastin and hnRNP A1 (Figure 5), thus implicating an interaction between classical and nonclassical nucleocytoplasmic transport, which is a novel experimental observation. How might the anti-M9 immune response directed at the nonclassical nucleocytoplasmic transport system alter the classical nucleocytoplasmic transport system? Although this is not yet known, several possibilities exist. Notably, both the nonclassical and classical nucleocytoplasmic transport pathways are tightly regulated and require the binding of RanGTP to a β-karyopherin (transportin for hnRNP A1 and a β-importin for spastin) to function (Figure 2).11,139–142,151 Thus, both pathways are regulated by the same system and an interruption in one may affect the other. For example, binding of anti-M9 antibodies to hnRNP A1 might interrupt the finely tuned regulation of RanGTP, thus altering the classical nucleocytoplasmic transport of spastin. Alternatively, anti-M9 antibodies might sterically hinder hnRNP A1’s binding to spastin protein. Finally, considering our data showing that spastin RNA binds hnRNP A1, anti-M9 antibodies might interfere with spastin’s transport and subsequent translation or localization to specific neuronal sites. Importantly, in addition to interaction with the nuclear pore and nucleocytoplasmic transport, spastin contributes to the function of other neuronal processes (Figure 5). Spastin contains an AAA site and thus is a member of the ATPases associated with various cellular activities, which are involved in microtubule regulation, as well as proteosome and endosome function.28,100,102 Spastin contains a microtubule interacting and trafficking protein site,100,152 and has been shown to play a role in microtubule stability and axonal transport in neurons,100 and in turn in normal synaptic growth and transmission.101 In addition, spastin has been shown to play an important role in axonal transport, which when disrupted results in neurodegeneration.28,99,100,152

Figure 4.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A1 localization following TNF-α exposure in neurons. Without TNF-α exposure, hnRNP A1 is localized to nuclei (*) in dNT-2 neurons (left panels) (blue nuclear stain is diamidino-2-phenylindole; green stain is immunohistochemistry using an anti-hnRNP A1 antibody). Following exposure to TNF-α (400 ng/mL, 50 mM glutamate, 30 minutes), hnRNP A1 is also found in the cytoplasm (arrowheads) and neuronal processes (arrow) of neurons (lower right panel).

Abbreviation: TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Figure 5.

Potential contribution of the anti-heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A1 M9 immune response to neurodegeneration in immune-mediated neurological disease. Multiple sclerosis and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis patients develop antibodies to an epitope contained within the M9 region of hnRNP A1 (box). hnRNP A1 has been shown to interact molecularly with spastin RNA and protein (box and figure). The anti-M9 immune response altered spastin RNA levels, which may alter spastin function at multiple sites within neurons (blue boxes). The combination of proinflammatory cytokines and the anti-M9 immune response might contribute to neurodegeneration in immune-mediated neurological disease.

Abbreviations: TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; SPG, spinal paraplegia gene.

Spastin is just one example of how the anti-hnRNP A1 M9 immune response might contribute to neurodegeneration. As shown in Table 2, other genes were altered by the anti-M9 immune response.11 Future studies are needed to tease out the details of how these other groups of genes might contribute to mechanisms of neurodegeneration, including those potentially related to the progressive cognitive decline seen in MS patients,35,153,154 which has not yet been addressed in this model.

Conclusion

Taken together, these data suggest that neurodegeneration in MS involves multiple processes. One of several possible links between autoimmunity and neurodegeneration in neurological disease has been described. The target is hnRNP A1 in neurons and the immune response is antibodies to M9, its shuttling domain required for nucleocytoplasmic transport. Anti-M9 antibodies identified integrated networks of genes that maintain neuronal and axonal function and contribute to mechanisms of neurodegeneration related to the clinical phenotype expressed by patients with immune-mediated neurological diseases, such as progressive MS and HAM/TSP. Comprehensive analyses of this type of phenotype-specific mechanism of neurodegeneration may reveal novel strategies to treat these unremitting progressive neurological diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work is based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs. This study was funded by a VA Merit Review Award (to MCL) and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Multiple Sclerosis Research Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Drs Michael Levin and Sangmin Lee have a patent pending titled “Biomarker for neurodegeneration in neurological disease.” All other authors report no conflicts of interest in this paper.

References

- 1.Dutta R, Trapp BD. Pathogenesis of axonal and neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2007;68(22 Suppl 3):S22–S31. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000275229.13012.32. discussion S43–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterson JW, Trapp BD. Neuropathobiology of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2005;23(1):107–129. vi–vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noseworthy J, Lucchinetti C, Rodgriguez M, Weinshenker B. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(13):938–952. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassmann H, Bruck W, Lucchinetti CF. The immunopathology of multiple sclerosis: an overview. Brain Pathol. 2007;17(2):210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filippi M, Rovaris M, Rocca MA. Imaging primary progressive multiple sclerosis: the contribution of structural, metabolic, and functional MRI techniques. Mult Scler. Jun. 2004;10(Suppl 1):S36–S44. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1029oa. discussion S44–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkhof F, Calabresi PA, Miller DH, Reingold SC. Imaging outcomes for neuroprotection and repair in multiple sclerosis trials. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(5):256–266. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeLuca GC, Ramagopalan SV, Cader MZ, et al. The role of hereditary spastic paraplegia related genes in multiple sclerosis. A study of disease susceptibility and clinical outcome. J Neurol. 2007;254(9):1221–1226. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0505-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soldan S, Berti R, Salem N, et al. Association of human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) with multiple sclerosis: increased IgM response to HHV-6 early antigen and detection of serum HHV-6 DNA. Nat Med. 1997;3(12):1394–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sriram S, Stratton C, Yao S, et al. Chlamydia pneumonaie infection of the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1999;46(1):6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thacker EL, Mirzaei F, Ascherio A. Infectious mononucleosis and risk for multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):499–503. doi: 10.1002/ana.20820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S, Xu L, Shin Y, et al. A potential link between autoimmunity and neurodegeneration in immune-mediated neurological disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;235(1–2):56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Levin MC. Molecular mimicry in neurological disease: what is the evidence? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(7–8):1161–1175. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7312-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SM, Morocos Y, Jang H, Stuart JM, Levin MC. HTLV-1 induced molecular mimicry in neurologic disease. In: Oldstone M, editor. Molecular Mimicry: Infection Inducing Autoimmune Disease. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levin MC, Lee SM, Kalume F, et al. Autoimmunity due to molecular mimicry as a cause of neurological disease. Nat Med. May. 2002;8(5):509–513. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wucherpfennig KW. Infectious triggers for inflammatory neurological diseases. Nat Med. 2002;8(5):455–457. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poeisz B, Ruscetti F, Gazdar A, Bunn P, Minna J, Gallo R. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1980;77(12):7415–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gessain A, Vernant J, Maurs L, et al. Antibodies to human T-lymphotropic virus I in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. Lancet. 1985;2:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osame M, Usuku K, Izumo S, et al. HTLV-I associated myelopathy, a new clinical entity. Lancet. 1986;1(8488):1031–1032. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin M, Lehky T, Flerlage N, et al. Immunopathogenesis of HTLV-1 associated neurologic disease based on a spinal cord biopsy from a patient with HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) N Engl J Med. 1997;336:839–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703203361205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin MC, Jacobson S. HTLV-I associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP): a chronic progressive neurologic disease associated with immunologically mediated damage to the central nervous system. J Neurovirol. 1997;3(2):126–140. doi: 10.3109/13550289709015802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araujo AQ, Silva MT. The HTLV-1 neurological complex. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(12):1068–1076. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verdonck K, Gonzalez E, Van Dooren S, Vandamme AM, Vanham G, Gotuzzo E. Human T-lymphotropic virus 1: recent knowledge about an ancient infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(4):266–281. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobson S. The NK cell as a new player in the pathogenesis of HTLV-I associated neurologic disease. Virulence. 2010;1(1):8–9. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.1.10327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin F, Bangham CR, Ciminale V, et al. Conference highlights of the 15th International Conference on Human Retrovirology: HTLV and related retroviruses, June 4–8, 2011. Leuven, Gembloux, Belgium. Retrovirology. 2011;8:86. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puccioni-Sohler M, Yamano Y, Rios M, et al. Differentiation of HAM/TSP from patients with multiple sclerosis infected with HTLV-I. Neurology. 2007;68(3):206–213. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251300.24540.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan RB, Bertorini TE, Levin MC. HTLV-1 and its neurological complications. Neurologist. 2001;7(5):271–278. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soderblom C, Blackstone C. Traffic accidents: molecular genetic insights into the pathogenesis of the hereditary spastic paraplegias. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109(1–2):42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salinas S, Proukakis C, Crosby A, Warner TT. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinical features and pathogenetic mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(12):1127–1138. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umehara F, Abe M, Koreeda Y, Izumo S, Osame M. Axonal damage revealed by accumulation of beta-amyloid precursor protein in HTLV-I-associated myelopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2000;176(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jernigan M, Morcos Y, Lee SM, Dohan FC, Jr, Raine C, Levin MC. IgG in brain correlates with clinicopathological damage in HTLV-1 associated neurologic disease. Neurology. 2003;60(8):1320–1327. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000059866.03880.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deluca GC, Ebers GC, Esiri MM. The extent of axonal loss in the long tracts in hereditary spastic paraplegia. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2004;30(6):576–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeLuca GC, Ebers GC, Esiri MM. Axonal loss in multiple sclerosis: a pathological survey of the corticospinal and sensory tracts. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 5):1009–1018. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izumo S. Neuropathology. Jun 21, 2010. Neuropathology of HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP) Epub. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trapp BD, Nave KA. Multiple sclerosis: an immune or neurodegenerative disorder? Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geurts JJ, Barkhof F. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(9):841–851. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kutzelnigg A, Lucchinetti CF, Stadelmann C, et al. Cortical demyelination and diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 11):2705–2712. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kornek B, Storch MK, Weissert R, et al. Multiple sclerosis and chronic autoimmune encephalomyelitis: a comparative quantitative study of axonal injury in active, inactive, and remyelinated lesions. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(1):267–276. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64537-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gold R, Linington C, Lassmann H. Understanding pathogenesis and therapy of multiple sclerosis via animal models: 70 years of merits and culprits in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis research. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 8):1953–1971. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aboul-Enein F, Weiser P, Hoftberger R, Lassmann H, Bradl M. Transient axonal injury in the absence of demyelination: a correlate of clinical disease in acute experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2006;111(6):539–547. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0047-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lassmann H. Multiple sclerosis: is there neurodegeneration independent from inflammation? J Neurol Sci. 2007;259(1–2):3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bjartmar C, Wujek JR, Trapp BD. Axonal loss in the pathology of MS: consequences for understanding the progressive phase of the disease. J Neurol Sci. 2003;206(2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lassmann H, van Horssen J. The molecular basis of neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(23):3715–3723. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennett JL, Stuve O. Update on inflammation, neurodegeneration, and immunoregulation in multiple sclerosis: therapeutic implications. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(3):121–132. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181880359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinman L. Mixed results with modulation of TH-17 cells in human autoimmune diseases. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(1):41–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McFarland HF, Martin R. Multiple sclerosis: a complicated picture of autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):913–919. doi: 10.1038/ni1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lisak RP. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis: defining the problem. Neurology. 2007;68(22 Suppl 3):S5–S12. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000275227.74893.bd. discussion S43–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis – the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):942–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frischer JM, Bramow S, Dal-Bianco A, et al. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain. May. 2009;132(Pt 5):1175–1189. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trapp B, Peterson J, Ransohoff R, Rudick R, Mork S, Bo L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(5):278–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lassmann H, Lucchinetti CF. Cortical demyelination in CNS inflammatory demyelinating diseases. Neurology. 2008;70(5):332–333. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000298724.89870.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lucchinetti CF, Popescu BF, Bunyan RF, et al. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2188–2197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peterson JW, Bo L, Mork S, Chang A, Trapp BD. Transected neurites, apoptotic neurons, and reduced inflammation in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(3):389–400. doi: 10.1002/ana.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisher E, Lee JC, Nakamura K, Rudick RA. Gray matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(3):255–265. doi: 10.1002/ana.21436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fisniku LK, Chard DT, Jackson JS, et al. Gray matter atrophy is related to long-term disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(3):247–254. doi: 10.1002/ana.21423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geurts JJ. Is progressive multiple sclerosis a gray matter disease? Ann Neurol. 2008;64(3):230–232. doi: 10.1002/ana.21485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Serafini B, Rosicarelli B, Magliozzi R, Stigliano E, Aloisi F. Detection of ectopic B-cell follicles with germinal centers in the meninges of patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2004;14(2):164–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Reeves C, et al. A gradient of neuronal loss and meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):477–493. doi: 10.1002/ana.22230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ganter P, Prince C, Esiri MM. Spinal cord axonal loss in multiple sclerosis: a post-mortem study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1999;25(6):459–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1999.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lovas G, Szilagyi N, Majtenyi K, Palkovits M, Komoly S. Axonal changes in chronic demyelinated cervical spinal cord plaques. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 2):308–317. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeLuca GC, Williams K, Evangelou N, Ebers GC, Esiri MM. The contribution of demyelination to axonal loss in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 6):1507–1516. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Evangelou N, DeLuca GC, Owens T, Esiri MM. Pathological study of spinal cord atrophy in multiple sclerosis suggests limited role of local lesions. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 1):29–34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Izumo S, Higuchi I, Ijichi T, et al. Neuropathological study in two autopsy cases of HTLV-1 associated myelopathy (HAM). In: Iwasaki Y, editor. Neuropathology of HAM/TSP in Japan; Proceedings of the First Workshop on Neuropathology of Retrovirus Infections; August 31, 1989; Tokyo, Japan. Sendai, Japan: Tohuku University Press; 1989. pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Izumo S, Umehara F, Osame M. HTLV-I-associated myelopathy. Neuropathology. 2000;20(Suppl):S65–S68. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2000.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evangelou IE, Oh U, Massoud R, Jacobson S. HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis: semiautomatic quantification of spinal cord atrophy from 3-dimensional MR images. J Neuroimaging. 2012 Feb 3; doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2011.00648.x. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Furby J, Hayton T, Anderson V, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging measures of brain and spinal cord atrophy correlate with clinical impairment in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008;14(8):1068–1075. doi: 10.1177/1352458508093617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Umehara F, Izumo S, Nakagawa M, et al. Immunocytochemical analysis of the cellular infiltrate in the spinal cord lesions in HTLV-I-associated myelopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1993;52(4):424–430. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matsuoka E, Takenouchi N, Hashimoto K, et al. Perivascular T cells are infected with HTLV-I in the spinal cord lesions with HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis: double staining of immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction in situ hybridization. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1998;96(4):340–346. doi: 10.1007/s004010050903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moritoyo T, Reinhart T, Moritoyo H, et al. Human T-lymphotropic virus type I associated myelopathy and tax gene expression in CD4+ T lymphocytes. Ann Neurol. 1996;40(1):84–90. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Araya N, Sato T, Yagishita N, et al. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and regulatory T cells in HTLV-1-associated neuroinflammatory disease. Viruses. 2011;3(9):1532–1548. doi: 10.3390/v3091532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matsuura E, Yamano Y, Jacobson S. Neuroimmunity of HTLV-I Infection. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010;5(3):310–325. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takenouchi N, Yao K, Jacobson S. Immunopathogensis of HTLV-I associated neurologic disease: molecular, histopathologic, and immunologic approaches. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2527–2539. doi: 10.2741/1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bangham CR, Osame M. Cellular immune response to HTLV-1. Oncogene. 2005;24(39):6035–6046. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bangham CR, Meekings K, Toulza F, et al. The immune control of HTLV-1 infection: selection forces and dynamics. Front Biosci. 2009;14:2889–2903. doi: 10.2741/3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bangham CR. The immune response to HTLV-I. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12(4):397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacobson S, Shida H, McFarlin DE, Fauci AS, Koenig S. Circulating CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for HTLV-I pX in patients with HTLV-I associated neurological disease. Nature. 1990;348(6298):245–248. doi: 10.1038/348245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lal RB, Giam C-Z, Coligan JE, Rudolph DL. Differential immune responsiveness to the immunodominant epitopes of regulatory proteins (tax and rex) in human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1-associated myelopathy. J Infect Dis. 1994;169(3):496–503. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kubota R, Furukawa Y, Izumo S, Usuku K, Osame M. Degenerate specificity of HTLV-1-specific CD8+ T cells during viral replication in patients with HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP) Blood. 2003;101(8):3074–3081. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goon PK, Hanon E, Igakura T, et al. High frequencies of Th1-type CD4(+) T cells specific to HTLV-1 Env and Tax proteins in patients with HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. Blood. 2002;99(9):3335–3341. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jeffery KJ, Usuku K, Hall SE, et al. HLA alleles determine human T-lymphotropic virus-I (HTLV-I) proviral load and the risk of HTLV-I-associated myelopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(7):3848–3853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Macnamara A, Rowan A, Hilburn S, et al. HLA class I binding of HBZ determines outcome in HTLV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(9):e1001117. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saxena A, Martin-Blondel G, Mars LT, Liblau RS. Role of CD8 T cell subsets in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(23):3758–3763. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schneider R, Mohebiany AN, Ifergan I, et al. B cell-derived IL-15 enhances CD8 T cell cytotoxicity and is increased in multiple sclerosis patients. J Immunol. 2011;187(8):4119–4128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamano Y, Araya N, Sato T, et al. Abnormally high levels of virus-infected IFN-gamma+ CCR4+ CD4+ CD25+ T cells in a retrovirus-associated neuroinflammatory disorder. PloS One. 2009;4(8):e6517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Norris PJ, Hirschkorn DF, DeVita DA, Lee TH, Murphy EL. Human T cell leukemia virus type 1 infection drives spontaneous proliferation of natural killer cells. Virulence. 2010;1(1):19–28. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.1.9868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nagai M, Usuku K, Matsumoto W, et al. Analysis of HTLV-1 proviral load in 202 HAM/TSP patients and 243 asymptomatic HTLV-1 carriers: high proviral load strongly predisposes to HAM/TSP. J Neurovirol. 1998;4(6):586–593. doi: 10.3109/13550289809114225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Olindo S, Lezin A, Cabre P, et al. HTLV-1 proviral load in peripheral blood mononuclear cells quantified in 100 HAM/TSP patients: a marker of disease progression. J Neurol Sci. 2005;237(1–2):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Montanheiro PA, Oliveira AC, Posada-Vergara MP, et al. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) proviral DNA viral load among asymptomatic patients and patients with HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005;38(11):1643–1647. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005001100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tattermusch S, Skinner JA, Chaussabel D, et al. Systems biology approaches reveal a specific interferon-inducible signature in HTLV-1 associated myelopathy. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(1):e1002480. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goon PK, Igakura T, Hanon E, et al. High circulating frequencies of tumor necrosis factor alpha- and interleukin-2-secreting human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-specific CD4+ T cells in patients with HTLV-1-associated neurological disease. J Virol. 2003;77(17):9716–9722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9716-9722.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Waxman SG. Axonal conduction and injury in multiple sclerosis: the role of sodium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(12):932–941. doi: 10.1038/nrn2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dutta R, Trapp B. Mechanisms of neuronal dysfunction and degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dutta R, McDonough J, Yin X, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):478–489. doi: 10.1002/ana.20736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Campbell GR, Ziabreva I, Reeve AK, et al. Mitochondrial DNA deletions and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(3):481–492. doi: 10.1002/ana.22109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haider L, Fischer MT, Frischer JM, et al. Oxidative damage in multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 7):1914–1924. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Trapp BD, Stys PK. Virtual hypoxia and chronic necrosis of demyelinated axons in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(3):280–291. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mahad DJ, Ziabreva I, Campbell G, et al. Mitochondrial changes within axons in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 5):1161–1174. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ferguson B, Matyszak MK, Esiri MM, Perry VH. Axonal damage in acute multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 3):393–399. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stokin GB, Lillo C, Falzone TL, et al. Axonopathy and transport deficits early in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2005;307(5713):1282–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1105681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.De Vos KJ, Grierson AJ, Ackerley S, Miller CC. Role of axonal transport in neurodegenerative diseases. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:151–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Roll-Mecak A, Vale RD. Structural basis of microtubule severing by the hereditary spastic paraplegia protein spastin. Nature. 2008;451(7176):363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature06482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Trotta N, Orso G, Rossetto MG, Daga A, Broadie K. The hereditary spastic paraplegia gene, spastin, regulates microtubule stability to modulate synaptic structure and function. Curr Biol. 2004;14(13):1135–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hazan J, Fonknechten N, Mavel D, et al. Spastin, a new AAA protein, is altered in the most frequent form of autosomal dominant spastic paraplegia. Nat Genet. 1999;23(3):296–303. doi: 10.1038/15472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lukong KE, Chang KW, Khandjian EW, Richard S. RNA-binding proteins in human genetic disease. Trends Genet. 2008;24(8):416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Orr HT. FTD and ALS: genetic ties that bind. Neuron. 2011;72(2):189–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gao FB, Taylor JP. RNA-binding proteins in neurological disease. Brain Res. 2012;1462:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Bennett CF, Cleveland DW, Yeo GW. Misregulated RNA processing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. 2012;1462:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Licatalosi DD, Darnell RB. Splicing regulation in neurologic disease. Neuron. 2006;52(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Darnell RB, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic syndromes involving the nervous system. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(16):1543–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Owens GP, Bennett JL, Lassmann H, et al. Antibodies produced by clonally expanded plasma cells in multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(6):639–649. doi: 10.1002/ana.21641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lovato L, Willis SN, Rodig SJ, et al. Related B cell clones populate the meninges and parenchyma of patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 2):534–541. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Keegan M, Pineda AA, McClelland RL, Darby CH, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Plasma exchange for severe attacks of CNS demyelination: predictors of response. Neurology. 2002;58(1):143–146. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Keegan M, Konig F, McClelland R, et al. Relation between humoral pathological changes in multiple sclerosis and response to therapeutic plasma exchange. Lancet. 2005;366(9485):579–582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Elovaara I, Kuusisto H, Wu X, Rinta S, Dastidar P, Reipert B. Intravenous immunoglobulins are a therapeutic option in the treatment of multiple sclerosis relapse. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(2):84–89. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31820a17f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Haas J, Maas-Enriquez M, Hartung HP. Intravenous immunoglobulins in the treatment of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis – results of a retrospective multicenter observational study over five years. Mult Scler. 2005;11(5):562–567. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1224oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):676–688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Boster A, Ankeny DP, Racke MK. The potential role of B cell-targeted therapies in multiple sclerosis. Drugs. 2010;70(18):2343–2356. doi: 10.2165/11585230-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Meinl E, Derfuss T, Krumbholz M, Probstel AK, Hohlfeld R. Humoral autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2010;306(1–2):180–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brown DA, Sawchenko PE. Time course and distribution of inflammatory and neurodegenerative events suggest structural bases for the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502(2):236–260. doi: 10.1002/cne.21307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Derfuss T, Linington C, Hohlfeld R, Meinl E. Axo-glial antigens as targets in multiple sclerosis: implications for axonal and grey matter injury. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88(8):753–761. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0632-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mathey EK, Derfuss T, Storch MK, et al. Neurofascin as a novel target for autoantibody-mediated axonal injury. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2363–2372. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rawes JA, Calabrese VP, Khan OA, DeVries GH. Antibodies to the axolemma-enriched fraction in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases. Mult Scler. 1997;3(6):363–369. doi: 10.1177/135245859700300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Norgren N, Edelstam A, Stigbrand T. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of neurofilament light in chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res Bull. 2005;67(4):264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sadatipour BT, Greer JM, Pender MP. Increased circulating antiganglioside antibodies in primary and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(6):980–983. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Srivastava R, Aslam M, Kalluri SR, et al. Potassium channel KIR4.1 as an immune target in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):115–123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cross AH, Waubant E. Antibodies to potassium channels in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):172–174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1204118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Levin M, Krichavsky M, Berk J, et al. Neuronal molecular mimicry in immune mediated neurologic disease. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(1):87–98. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lee SM, Dunnavant FD, Jang H, Zunt J, Levin MC. Autoantibodies that recognize functional domains of hnRNPA1 implicate molecular mimicry in the pathogenesis of neurological disease. Neurosci Lett. 2006;401(1–2):188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee S, Shin Y, Marler J, Levin MC. Post-translational glycosylation of target proteins implicate molecular mimicry in the pathogenesis of HTLV-1 associated neurological disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;204(1–2):140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lee S, Shin Y, Clark D, Gotuzzo E, Levin MC. Cross-reactive antibodies to target proteins are dependent upon oligomannose glycosylated epitopes in HTLV-1 associated neurological disease. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(4):736–745. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Dreyfuss G, Kim VN, Kataoka N. Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(3):195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Han SP, Tang YH, Smith R. Functional diversity of the hnRNPs: past, present and perspectives. Biochem J. 2010;430(3):379–392. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Levin MC, Lee SM, Morcos Y, Brady J, Stuart J. Cross-reactivity between immunodominant human T lymphotropic virus type I tax and neurons: implications for molecular mimicry. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(10):1514–1517. doi: 10.1086/344734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kalume F, Lee SM, Morcos Y, Callaway JC, Levin MC. Molecular mimicry: cross-reactive antibodies from patients with immune-mediated neurologic disease inhibit neuronal firing. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77(1):82–89. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.García-Vallejo F, Domínguez MC, Tamayo O. Autoimmunity and molecular mimicry in tropical spastic paraparesis/human T-lymphotropic virus-associated myelopathy. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005;38(2):241–250. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005000200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sueoka E, Yukitake M, Iwanaga K, Sueoka N, Aihara T, Kuroda Y. Autoantibodies against heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein B1 in CSF of MS patients. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(6):778–786. doi: 10.1002/ana.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yukitake M, Sueoka E, Sueoka-Aragane N, et al. Significantly increased antibody response to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins in cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients but not in patients with human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. J Neurovirol. 2008;14(2):130–135. doi: 10.1080/13550280701883840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Douglas J, Gardner L, Lee S, Shin Y, Groover C, Levin MC. Antibody transfection into neurons as a tool to study disease pathogenesis. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2012;67 doi: 10.3791/4154. pii 4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Schmued LC, Stowers CC, Scallet AC, Xu L. Fluoro-Jade C results in ultra high resolution and contrast labeling of degenerating neurons. Brain Res. 2005;1035(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Stewart M. Molecular mechanism of the nuclear protein import cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(3):195–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Conti E, Müller CW, Stewart M. Karyopherin flexibility in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16(2):237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Cook A, Bono F, Jinek M, Conti E. Structural biology of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:647–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.161529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Lee BJ, Cansizoglu AE, Suel KE, Louis TH, Zhang Z, Chook YM. Rules for nuclear localization sequence recognition by karyopherin beta 2. Cell. 2006;126(3):543–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Homayouni R, Heinrich K, Wei L, Berry MW. Gene clustering by latent semantic indexing of MEDLINE abstracts. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(1):104–115. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Michael WM, Choi M, Dreyfuss G. A nuclear export signal in hnRNP A1: a signal-mediated, temperature-dependent nuclear protein export pathway. Cell. 1995;83(3):415–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hanz S, Perlson E, Willis D, et al. Axoplasmic importins enable retrograde injury signaling in lesioned nerve. Neuron. 2003;40(6):1095–1104. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Thompson KR, Otis KO, Chen DY, Zhao Y, O’Dell TJ, Martin KC. Synapse to nucleus signaling during long-term synaptic plasticity; a role for the classical active nuclear import pathway. Neuron. 2004;44(6):997–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Yudin D, Hanz S, Yoo S, et al. Localized regulation of axonal RanGTPase controls retrograde injury signaling in peripheral nerve. Neuron. 2008;59(2):241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Kim JY, Shen S, Dietz K, et al. HDAC1 nuclear export induced by pathological conditions is essential for the onset of axonal damage. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(2):180–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Miller RH. Renegade nuclear enzymes disrupt axonal integrity. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(2):143–144. doi: 10.1038/nn0210-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Beetz C, Brodhun M, Moutzouris K, et al. Identification of nuclear localisation sequences in spastin (SPG4) using a novel Tetra-GFP reporter system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318(4):1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Rebane A, Aab A, Steitz JA. Transportins 1 and 2 are redundant nuclear import factors for hnRNP A1 and HuR. RNA. 2004;10(4):590–599. doi: 10.1261/rna.5224304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Salinas S, Carazo-Salas RE, Proukakis C, Schiavo G, Warner TT. Spastin and microtubules: functions in health and disease. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(12):2778–2782. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Lazeron RH, de Sonneville LM, Scheltens P, Polman CH, Barkhof F. Cognitive slowing in multiple sclerosis is strongly associated with brain volume reduction. Mult Scler. 2006;12(6):760–768. doi: 10.1177/1352458506070924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Lazeron RH, Boringa JB, Schouten M, et al. Brain atrophy and lesion load as explaining parameters for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(5):524–531. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1201oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]