Summary

Background

Prison suicide rates, rate ratios, and associations with prison-related factors need clarification and updating. We examined prison suicide rates in countries where reliable information was available, associations with a range of prison-service and health-service related factors, how these rates compared with the general population, and changes over the past decade.

Methods

We collected data for prison suicides in 24 high-income countries in Europe, Australasia, and North America from their prison administrations for 2011–14 to calculate suicide rates and rate ratios compared with the general population. We used meta-regression to test associations with general population suicide rates, incarceration rates, and prison-related factors (overcrowding, ratio of prisoners to prison officers or health-care staff or education staff, daily spend, turnover, and imprisonment duration). We also examined temporal trends.

Findings

3906 prison suicides occurred during 2011–14 in the 24 high-income countries we studied. Where there was breakdown by sex (n=2810), 2607 (93%) were in men and 203 (7%) were in women. Nordic countries had the highest prison suicide rates of more than 100 suicides per 100 000 prisoners apart from Denmark (where it was 91 per 100 000), followed by western Europe where prison suicide rates in France and Belgium were more than 100 per 100 000 prisoners. Australasian and North American countries had rates ranging from 23 to 67 suicides per 100 000 prisoners. Rate ratios, or rates compared with those in the general population of the same sex and similar age, were typically higher than 3 in men and 9 in women. Higher incarceration rates were associated with lower prison suicide rates (b = –0·504, p = 0·014), which was attenuated when adjusting for prison-level variables. There were no associations between rates of prison suicide and general population suicide, any other tested prison-related factors, or differing criteria for defining suicide deaths. Changes in prison suicide rates over the past decade vary widely between countries.

Interpretation

Many countries in northern and western Europe have prison suicide rates of more than 100 per 100 000 prisoners per year. Individual-level information about prisoner health is required to understand the substantial variations reported and changes over time.

Funding

Wellcome Trust and the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

Introduction

Prison suicide is an international problem, and rates of suicide in prisoners are higher than in general populations.1–3 In England and Wales, a five to six times excess of suicides in male prisoners compared with the general population has been reported;1,4 whereas, in female prisoners, rate ratios are 20 times higher than in the general population.1,5 In some countries, these rates have been increasing. For example, in 2016, the rate of prison suicides in England and Wales reached its highest level since 1999. Research on rates and rate ratios of suicide in prisons needs updating, as it is not known whether rate ratios are also rising and whether any changes are associated with prison-related factors. A clearer understanding of factors explaining the elevated risks can assist in suicide prevention initiatives; many countries already include specific prisoner suicide prevention in national strategies.

Individual-level characteristics associated with prison suicide suggest that psychiatric illness, substance misuse, and repetitive self-harm are known important risk factors for suicide.6,7 However, less is known about prison and health service-level factors, which might be subject to public health and policy change. A recent concern has been the problem of prison overcrowding, with 119 of 205 countries currently reported to be exceeding their official prison capacity,8 but findings of an association with prison suicide are inconsistent. A number of studies have found a positive correlation between overcrowding and prison suicide,9–12 but others have found the opposite,13 14 possibly due to a protective effect of the double occupation of cells designed for single use. Low staff engagement, negative staff–prisoner relationships, and high prison population turnover rates are also potential explanations, but evidence is limited.15–17

In this study, we have investigated prison suicide between 2011 and 2014 in 24 high-income countries across three continents, and examined suicide rates, rate ratios compared with the general population, and associations with a range of prison-level and ecological factors. Additionally, we have examined trends in prison suicide rates over the period of 2003–14.

Methods

Study design and data sources

24 countries (table 1) were chosen based on the availability of data from reliable recording methods. Information about all self-inflicted deaths during 2011–14 inclusive was collected from the 24 countries from publicly available statistics on government or prison service websites (using a Google search, including the name of the country and a combination of terms including “prison”, “justice”, “custody”, “suicide”, “self-inflicted”, “death”, and “mortality”). We also contacted prison service research departments and collected information from the Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics SPACE I publication,18 which collects statistics from governmental bodies regarding imprisonment and penal institutions in Council of Europe member states. Details of data sources for each country are reported in the appendix (pp 6–8).

Table 1. Definitions of suicide in custody.

| Necessary to prove intent? | Includes suicides or self-inflicted deaths in prison hospitals? | Includes suicides or self-inflicted deaths in community hospitals? | Includes suicides or self-inflicted deaths outside prison (ie, during leave)? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Europe | ||||

| Croatia | NA | Yes | No | Yes |

| Czech Republic | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Poland | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Northern Europe | ||||

| Denmark | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| Finland | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Iceland | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| Norway | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Sweden | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| Western Europe | ||||

| Belgium | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| England and Wales | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| France | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Germany | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| Ireland | NA | Yes | No | No |

| Netherlands | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Northern Ireland | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Scotland | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Switzerland | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Southern Europe | ||||

| Italy | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| Portugal | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| Spain | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Australasia | ||||

| Australia | No | NA | NA | NA |

| New Zealand | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| North America | ||||

| Canada | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| USA total | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Data were extracted from government websites, a European Union prisons database (SPACE I), and directly from national prison services. NA=not available.

Countries varied in their definitions of deaths classified as suicide in custody; some classified suicides as any death resulting from self-inflicted injury, regardless of intention (which resulted in fewer deaths being classified as “undetermined”), while other countries based their decision on proving intent. 18 countries included deaths that occurred in the prison hospital or in community hospitals (where a prisoner was moved), and nine countries included suicides that occurred during permitted leave (table 1). However, when rates were pooled for countries with particular defining criteria for prison suicide, there was no difference in rates (appendix p 11).

Information about age-adjusted rates of suicides (ICD-10 codes X60–X64) per 100 000 in the general adult population aged 30–49 years for the year 2012 was obtained for the majority of countries from the WHO Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative report.19 For England and Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland, this information was collected from government websites.

Prison and health-service related factors

Based on previous research, we tested a number of ecological prison variables that have been proposed as suicide risk factors,9–12,15–17,20,21 for associations with prison suicide rates. These variables were incarceration rates, which were calculated per 100 000 people in the general adult population; rates of overcrowding, which were calculated using prison population figures and prison capacity figures for each of the four years; ratios of prisoners to prison staff (which were separated into officers, health-care staff, and education staff); prison population turnover ratios, which were calculated as:

mean cost per prisoner per day (converted into Euros); rates of forensic psychiatric inpatient beds per 100 000 general population22 (available for five countries for 2011–12); the management of prison health care (public health-care system vs national justice system);23 and mean length of imprisonment (in months). Information about these prison variables was not available for all 4 years for all countries, so means were taken for available years.

We also collected data for prison suicides from 2003 to 2010, using the same methods as this study, to examine whether there had been changes in rates of suicide over time for the 12 countries where data were available.

Statistical analysis

We used the number of suicide deaths and annual prison populations to calculate annual rates of suicide per 100 000 prisoners for each year from 2011–14, typically based on a mid-year census date. We only included countries with five or more suicide events in prisons because a smaller number of suicide events would not have allowed us to calculate rate ratios accurately. Australia, Canada, Northern Ireland, and Poland did not have data for prison suicides available for 2014, so averages were taken for 2011–13. The sex breakdown of deaths was not available in four countries: Australia, Canada, Poland, and Switzerland. To account for the size of each country’s population, we conducted meta-regression analyses comparing rates of prison suicide in men, women, and both sexes combined, with each of the factors described above. We then did a multivariable meta-regression analysis to investigate whether correlations retained statistical significance when adjusting for other factors. These factors were those that had been found to be associated with prison suicide rates in previous research and those that we found to correlate most highly with prison suicide rate. We also calculated Pearson’s correlations between prison suicide rates and all other variables to support findings from the meta-regression analyses. We did not do analyses for countries with fewer than five suicides over the 4 year period, because statistical power was too low. We excluded the USA in one analysis (for incarceration rates) because it was an outlier, with an incarceration rate of more than eight times higher than the majority of other countries.

We also completed a number of sub-analyses. First, we did linear regression analyses to investigate temporal trends of prison suicide rates for the years 2003–14. Second, we compared mean prison suicide rates for 2003–07 and 2011–14 for men and women separately. Third, we calculated rates of prison suicides using an alternative denominator that accounted for throughput. This approach assumed the number of receptions of presentenced or remand prisoners was a more appropriate denominator to determine rates7 rather than a mid-year census. It was calculated as follows:

Fourth, we investigated whether varying definitions of prison suicide influenced rates of prison suicide by calculating pooled estimates of prison suicide rates stratified by categories of definitions. Fifth, we calculated pooled estimates of prison suicide rates and rate ratios on the basis of length of imprisonment. Finally, we compared prison suicide rates between the three primary types of correctional institution in the USA: local jails, state prisons, and federal prisons.

Stata version 14 was used for all statistical analyses. Because data were anonymised and provided in summary form, no ethical approval was sought, and the study was conducted according to the guidelines governing research from the Declaration of Helsinki.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

3906 prison suicides occurred between 2011 and 2014 in 24 countries (table 2). Information about sex was available for 2810 (72%) prison suicides, with 2607 (93%) suicides in men and 203 (7%) suicides in women.

Table 2. Number and rates of suicide in prisoners compared with the general population.

| Total number of prison suicides, both genders (2011–14) | Annual suicide rate per 100 000 prisoners (including pretrial detainees)* | Annual suicide rate per 100 000 general population aged 30–49 years† | Rate ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | 95% CI | Rate | 95% CI | p value | |||

| Eastern Europe | |||||||

| Croatia | 2 | 10 | 0–29 | 14·6 | 0·7 | 0·1–11·4 | 0·75 |

| Czech Republic | 44 | 54 | 39–70 | 17·8 | 3·1 | 1·7–5·6 | 0·00027 |

| Poland | 59* | 24 | 21–28 | 24·6 | 1·0 | 0·6–1·6 | 0·93 |

| Northern Europe | |||||||

| Denmark | 14 | 91 | 60–122 | 12·9 | 7·0 | 4·1–11·8 | <0·0001 |

| Finland | 13 | 103 | 100–105 | 21·0 | 4·8 | 2·4–20·2 | 0·0038 |

| Iceland | 1 | 165 | 0–487 | 28·4 | 5·8 | 0·1–297·2 | 0·40 |

| Norway | 26 | 180 | 98–262 | 12·9 | 14·0 | 6·4–30·5 | <0·0001 |

| Sweden | 26 | 104 | 90–118 | 14·1 | 7·4 | 3·4–16·1 | <0·0001 |

| Western Europe | |||||||

| Belgium | 57 | 114 | 99–129 | 24·1 | 4·7 | 2·8–8·0 | <0·0001 |

| England and Wales | 284 | 83 | 66–100 | 13·6 | 6·1 | 4·8–7·7 | <0·0001 |

| France | 467 | 176 | 169–183 | 19·3 | 9·1 | 8·3–10·0 | <0·0001 |

| Germany | 220 | 81 | 75–88 | 12·7 | 6·4 | 4·9–8·4 | <0·0001 |

| Ireland | 8 | 47 | 32–63 | 15·7 | 3·0 | 0·8–12·2 | 0·34 |

| Netherlands | 43 | 99 | 53–145 | 13·0 | 7·6 | 4·2–14·0 | <0·0001 |

| Northern Ireland | 2‡ | 29 | 0–106 | 20·1 | 1·5 | 0·1–23·4 | 0·65 |

| Scotland | 22 | 69 | 44–93 | 26·2 | 2·6 | 1·1–6·1 | 0·027 |

| Switzerland | 26 | 98 | 49–146 | 11·5 | 8·5 | 3·9–18·9 | <0·0001 |

| Southern Europe | |||||||

| Italy | 204 | 81 | 69–93 | 6·7 | 12·1 | 9·1–16·0 | <0·0001 |

| Portugal | 59 | 108 | 69–147 | 10·4 | 10·4 | 6·2–17·5 | <0·0001 |

| Spain | 95 | 43 | 30–55 | 7·8 | 5·5 | 3·7–8·2 | <0·0001 |

| Australasia | |||||||

| Australia | 37‡ | 40 | 29–51 | 17·2 | 2·3 | 1·3–4·1 | 0·0069 |

| New Zealand | 23 | 67 | 18–115 | 13·2 | 5·1 | 2·2–11·6 | 0·00015 |

| North America | |||||||

| Canada | 31‡ | 27 | 0–48 | 11·4 | 2·3 | 1·2–4·3 | <0·0001 |

| USA | 2143 | 23 | 21–26 | 17·4 | 1·3 | 1·2–1·5 | <0·0001 |

Annual rates calculated based on however many years available between 2011 and 2014.

Annual rates for the year 2012.

Total in a 3 year period (2011–13).

Rates of prison suicide varied considerably (table 2), ranging from 23 per 100 000 prisoners in the USA, to 180 per 100 000 prisoners in Norway. Six countries with more than five suicide events had rates greater than 100 per 100 000 prisoners: Norway, France, Belgium, Portugal, Sweden, and Finland. In men, suicide rates ranged from 43 per 100 000 prisoners in local US jails to 183 per 100 000 prisoners in Norway (appendix p 3). In women, rates varied from 30 per 100 000 prisoners in local US jails to 363 per 100 000 prisoners in France (appendix p 4). Suicide rates were not typically higher in female prisoners than in male prisoners.

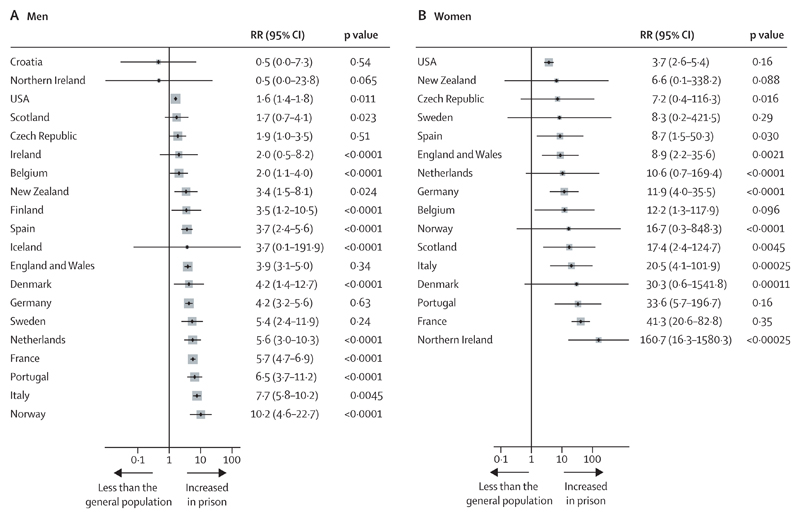

Comparing rates of prison suicide with general population rates, rate ratios for both sexes combined ranged from 1 in Poland to 14 in Norway (table 2). Rate ratios for men ranged from 2 in local US jails, to 10 in Norway (figure 1), excluding the USA, which is an outlier. Rate ratios for women were generally higher, ranging between 4 in local US jails and 41 in France (figure 1). French prison suicide figures include prisoners who have died in community settings, including hospital and permitted leave. However, when these numbers are excluded, the French rate remains the second highest (at 156 per 100 000 prisoners).

Figure 1. Rate ratios of suicide in prisoners compared with the general population.

RR=rate ratio.

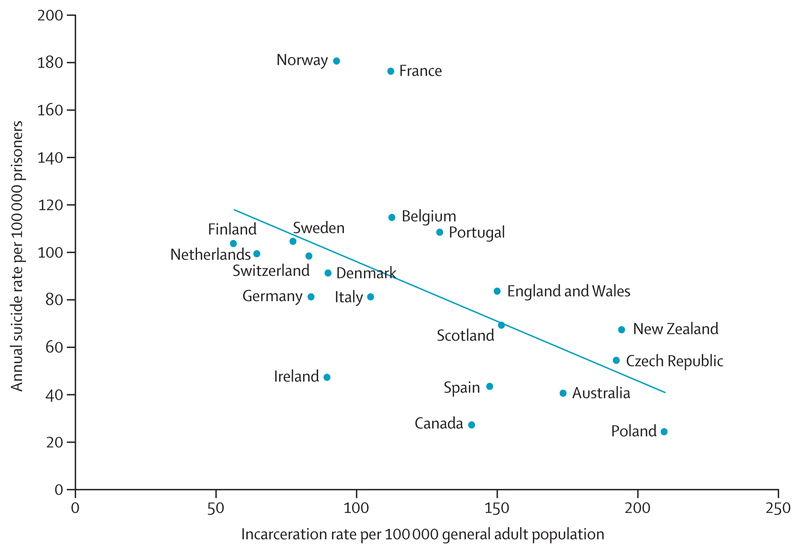

Meta-regression indicated a significant association between rates of incarceration and prison suicide rates when both sexes were combined (b=–0·504, p=0·014, n=20; figure 2). When the USA was included in the analysis, the effect was attenuated (b=–0·103, p=0·056, n=21; appendix p 5). When prison suicide rates were meta-regressed on incarceration rates and other factors were adjusted for (general population suicide rate, rate of overcrowding, and mean daily spend per prisoner), incarceration rates were not significantly associated with prison suicide rates (b=–0·343, p=0·20, n=19).

Figure 2. Rates of prison suicide compared with rates of incarceration.

Data are for men and women combined. USA was not included in this analysis because it is an outlier (appendix p 17).

There were no significant associations between any other prison-related variable and rates of prison suicide when both sexes were combined (table 3), nor when men and women were analysed separately. Further correlation analyses supported the findings from the meta-regression analyses (appendix p 5).

Table 3. Results of meta-regression analyses comparing prison suicide rate with general population suicide rate, incarceration rate, and other prison-level variables.

| Number of countries (n)* | Beta coefficient (b) | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual suicide rate per 100 000 general population aged 30–49 years | 20 | –0·002 | –3·886 to 3·88 | 0·99 |

| Incarceration rate per 100 000 general population | 20 | –0·504 | –0·895 to –0·114 | 0·014 |

| Rate of overcrowding | 20 | 0·987 | –0·449 to 2·414 | 0·17 |

| Ratio of prisoners to prison officers | 18 | –13·372 | –32·645 to 5·900 | 0·16 |

| Ratio of prisoners to health-care staff | 11 | 0·010 | –0·081 to 0·100 | 0·81 |

| Ratio of prisoners to educational staff | 11 | –0·040 | –0·240 to 0·160 | 0·66 |

| Mean daily spend per prisoner | 19 | 0·206 | –0·033 to 0·444 | 0·086 |

| Prison population turnover ratio | 13 | –0·167 | –2·092 to 1·759 | 0·85 |

| Management of prison health-care system† | 10 | 39·898 | –19·930 to 99·726 | 0·16 |

| Mean forensic inpatient bed rate | 5 | 1·783 | –5·492 to 9·057 | 0·49 |

| Mean length of imprisonment | 16 | –1·309 | –4·633 to 2·015 | 0·41 |

Countries with five events of suicide or fewer (n=3) and the USA were excluded from these analyses.

Categorised as: 1=National Health Service; 2=Justice System.

Between the years 2003 and 2014, prison suicide rates significantly decreased in Scotland (b=–0·777, p=0·0050; appendix p 14). Other included countries showed no significant changes over time (appendix p 9), including when we extended data to include 2015 and 2016 for England and Wales.

Prison suicide rates changed more than 40% in one-third of countries (4 of 12) for men and more than half (4 of 7) for women when we compared rates of the period 2011–2014 with 2003–07 (appendix pp 15,16). Using an alternative denominator that took into account throughput of prisoners, we found a reduction of 25% or more in prison suicide rates and rate ratios for seven countries: Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the USA (appendix p 10). There was no significant effect of prison suicide definition on rates when different definitions of suicide were used (appendix p 11) or by three categories of length of imprisonment (appendix p 12).

In the USA, local jails had the highest prison suicide rate (45 per 100 000 prisoners) compared with state prisons (16 per 100 000 prisoners) and federal prisons (11 per 100 000 prisoners; appendix p 13), with no clear associations between US prison suicide rates and incarceration rates (r=0·10, p=0·94, n=3) or rates of overcrowding (r=–0·85, p=0·36, n=3).

Discussion

We report on 3906 prison suicides in 24 countries between 2011 and 2014, and tested associations between suicide rates and 11 prison and health-service related factors. Compared with a previous ecological study of prison suicides in 2003–07,1 the current investigation has doubled the number of countries investigated, added new ecological factors, and investigated temporal trends in prison suicide rates.

Nordic countries had the highest prison suicide rates of more than 100 suicides per 100 000 prisoners in all but Denmark (where it was 91 per 100 000), followed by western Europe where prison suicide rates in France and Belgium were more than 100 per 100 000 prisoners. Australasian and North American countries had lower rates, ranging from 23 to 67 suicides per 100 000 prisoners. The high rates of prison suicide in Norway and France compared with other countries are notable. A possible explanation for these higher suicide rates could be a broader definition of suicide in custody for the country in question. In Norway, for example, deaths by suicide of prisoners outside prison are included as prison suicides (eg, if the individual dies in hospital or during community leave while still a prisoner). However, Norway has been assessed as having good validity and reliability for suicide classification,24 so the high rates are unlikely to be inflated. Similarly, French prison suicide figures include prisoners who have died in community settings including hospital and permitted leave; however, even when these numbers are excluded, the French rate remains the second highest. Furthermore, differences in definitions of prison suicide do not appear to affect pooled estimates of prison suicide rates (appendix p 11).

Rate ratios, or rates compared with those in the general population of the same sex and similar age, were typically higher than 3 in men and 9 in women, and provide an updated picture of the high relative risks of prison suicide, and that the relative excess is higher in female prisoners than in male prisoners. However, the higher rate ratios in women than men were not clearly associated with higher rates of prison suicide in women (appendix pp 3,4). Rate ratios were higher in Nordic and other northern European countries compared with northern America and Australasia. Central and southern Europe had wide variations.

We observed a number of findings with relation to temporal trends. The first was a reduction from 2003 to 2014 in prison suicide rates in Scotland. One of the explanations for this change was changes in drug treatment within custody.25 A second finding was the lack of any clear temporal trends for England and Wales, Belgium, Netherlands, and Sweden. Further research should examine trends in other countries.

One explanation for the negative association between prison suicide rates and incarceration rates is that prisoners in countries with lower incarceration rates are more likely to have committed more serious and violent crimes or have higher rates of mental illness, both of which are associated with increased suicide risk.20 In countries with high incarceration rates, the prison population is likely to be more heterogeneous leading to a dilution of high-risk groups. Based on this finding, future research should investigate associations between offence categories and prison suicide rates.

Most of the examined prison-level factors were not associated with prison suicide rates, suggesting that prison suicides are likely to be the result of a complex interaction of different factors, and not merely due to the prison environment.21 Studying these factors within countries could be informative, and their interaction might also provide some explanation. Nevertheless, this study underscores the importance of individual factors for current suicide prevention efforts, which have shown that there are replicable associations with ethnicity, sentence length, self-harm, and a number of clinical factors.20 To supplement these, more sensitive markers of health care need to be routinely recorded, which most data sources are lacking. These markers would include details of how many people are engaged in active treatment (pharmacological or psychological), and the extent and quality of prison health care, including pathways from screening to treatment. Other prison ecological factors that might have been informative include assault rates within prison, rates of self-harm, amount of daily meaningful activity,9 prisoner numbers involved in employment, education, or vocational training, and access to ligature points. These factors were reported for very few of the included countries. In addition, many important risk factors are present in prisoners before incarceration, including mental health, substance misuse, and personality problems, together with childhood and more recent traumatic and other adverse experiences.26–28

We have collected data from 24 countries over a 4-year period, which have allowed for an investigation of ecological factors. Our data were collected from high-quality data sources, with much coming directly from each country’s prison service research administration. However, an important limitation is differences in the definition of suicide in custody, which might contribute to variability in suicide rates. We have documented definitions of suicide, so that rates can be interpreted accordingly and have shown that the effect of prison suicide definition may be minimal (appendix p 11).

The data used in this study included prisoners in pretrial detention. Because disaggregated suicide data were not available, it was not possible to examine whether reported associations with prison factors are relevant to solely pretrial detainees. Additionally, we were limited by the range of ecological factors available and the availability of disaggregated data regarding the type of prison facility within each country.

Overall, our findings suggest that there are no simple ecological explanations for prison suicide. Rather, it is likely to be due to complex interactions between individual-level and ecological factors. Thus, suicide prevention initiatives need to draw on multidisciplinary approaches that address all parts of the criminal justice system and address individual and system-level risk factors.21 Future work should focus on within-country investigation of psychiatric health-care provision and other potentially more relevant ecological factors, in combination with established individual suicide risk factors, to help gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to suicide in prison. Finally, this study underscores the need for national strategies to address the problem of prison suicide.

Supplementary Material

See Online for appendix

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed from Jan 1, 2007, to June 31, 2017, using the search terms (prison* OR jail* OR incarcerat*) AND (suicid* OR self harm* OR self-harm*) AND (prevalen* OR inciden* OR rate* OR frequen*), with no language restrictions. We found one international study and four national studies (France, Germany, UK, and USA) that reported rates of prison suicides, as well as two investigations of the association between ecological factors and prison suicide rates. The international study provided information about prison suicide rates in 12 countries from 2003–07 and showed an elevated risk of suicide for prisoners compared with the general population, with a higher proportionate excess in women. No associations were found between rates of prison suicide and general population suicide rates or incarceration rates. The four national studies confirmed elevated rate ratios. The two reports examining ecological prison factors presented contrasting findings on the prison environment. We identified no international studies of prison suicide rates that also investigated associations with environmental prison factors.

Added value of this study

In this study, using data for 3906 prison suicides from 24 high-income countries, we found an elevated risk of suicide among prisoners compared with the general population in all countries with more than five suicide events in prisons; in men, this risk was at least two-fold and in women it was at least four-fold. We found a significant association between rate of prison suicide and rate of incarceration (b=–0.504, p=0·014); however, this effect was attenuated when other ecological factors (general population suicide rates, overcrowding, and average daily spend per prisoner) were adjusted for. Additionally, rates of prison suicides have changed over the past decade in countries for which data were available, with a decrease in Scotland.

Implications of all the available evidence

The lack of any strong associations between prison-level factors and prison suicide rates suggest that individual-level factors or interactions between them and the prison environment might provide more explanation than solely focusing on prison-level factors for the large variations in prison suicide rates in different countries. Reporting standards for prison suicide need improvement so that more granular data for possible risk factors can be examined.

Acknowledgments

SF is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Clinical Science (202836/Z/16/Z). KH is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator and is supported by Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Footnotes

Contributors

SF conceived and designed the study, drafted and critically revised the paper. TR did the data extraction, analyses, created tables and figures and assisted with drafting and critically revising the paper. KH assisted in the drafting and critically revised the paper.

Declaration of interests

SF reports personal fees from the Prisoner Ombudsman for Northern Ireland, outside the submitted work. TR and KH declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Fazel S, Grann M, Kling B, et al. Prison suicide in 12 countries: an ecological study of 861 suicides during 2003–2007. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:191–95. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duthé G, Hazard A, Kensey A, et al. Suicide among male prisoners in France: a prospective population-based study. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;233:273–77. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joukamaa M. Prison suicide in Finland, 1969–1992. Forensic Sci Int. 1997;89:167–74. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(97)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazel S, Benning R, Danesh J. Suicides in male prisoners in England and Wales, 1978–2003. Lancet. 2005;366:1301–02. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fazel S, Benning R. Suicides in female prisoners in England and Wales, 1978–2004. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:183–84. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazel S, Wolf A, Geddes JR. Suicide in prisoners with bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Bipolar Dis. 2013;15:491–95. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawton K, Linsell L, Adeniji T, et al. Self-harm in prisons in England and Wales: an epidemiological study of prevalence, risk factors, clustering, and subsequent suicide. Lancet. 2014;383:1147–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute for Criminal Policy Research. Highest to lowest - occupancy level based on official capacity. [accessed May 19, 2017];2017 http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/occupancy-level.

- 9.Leese M, Thomas S, Snow L. An ecological study of factors associated with rates of self-inflicted death in prisons in England and Wales. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2006;29:355–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabe K. Prison structure, inmate mortality and suicide risk in Europe. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2012;35:222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huey MP, McNulty TL. Institutional conditions and prison suicide: conditional effects of deprivation and overcrowding. Prison J. 2005;85:490–514. [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Ginneken EFJC, Sutherland A, Molleman T. An ecological analysis of prison overcrowding and suicide rates in England and Wales, 2000–2014. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2017;50:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duthé G, Hazard A, Kensey A, et al. Suicide in prison: a comparison between France and its European neighbours. Population & Societies. 2009:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fruehwald S, Frottier P, Ritter K, et al. Impact of overcrowding and legislational change on the incidence of suicide in custody: experiences in Austria, 1967–1996. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2002;25:119–28. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(01)00106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konrad N, Daigle MS, Daniel AE, et al. Preventing suicide in prisons, Part I: Recommendations from the International Association for Suicide Prevention Task Force on Suicide in Prisons. Crisis. 2007;28:113–21. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.28.3.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebling A. The role of the prison environment in prison suicide and prisoner distress. In: Dear GE, editor. Preventing suicide and other self-harm in prison. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laishes J. Inmate suicides in the Correctional Service of Canada. Crisis. 1997;18:157–62. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.18.4.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aebi MF, Delgrande N. SPACE I. 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015. [accessed May 19, 2017]; http:/wp.unil.ch/space/space-i/annual-reports/

- 19.WHO. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. World Health Organization; 2014. [accessed May 19, 2017]. http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazel S, Cartwright J, Norman-Nott A, et al. Suicide in prisoners: a systematic review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1721–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marzano L, Hawton K, Rivlin A, et al. Prevention of suicidal behavior in prisons. Crisis. 2016;37:323–34. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chow WS, Priebe S. How has the extent of institutional mental healthcare changed in Western Europe? Analysis of data since 1990. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010188. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fazel S, Hayes AJ, Bartellas K, et al. Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:871–81. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30142-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tøllefsen IM, Helweg-Larsen K, Thiblin I, et al. Are suicide deaths under-reported? Nationwide re-evaluations of 1800 deaths in Scandinavia. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009120. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bird SM. Changes in male suicides in Scottish prisons: 10-year study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:446–49. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marzano L, Fazel S, Rivlin A, et al. Near-lethal self-harm in women prisoners: contributing factors and psychological processes. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2011;22:863–84. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marzano L, Hawton K, Rivlin A, et al. Psychosocial influences on prisoner suicide: a case-control study of near-lethal self-harm in women prisoners. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:874–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivlin A, Fazel S, Marzano L, et al. The suicidal process in male prisoners making near-lethal suicide attempts. Psychology, Crime & Law. 2013;19:305–27. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.