Abstract

The mammalian IAPs, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 and 2 (cIAP1 and cIAP2), play pivotal roles in innate immune signaling and inflammatory homeostasis, often working in parallel or in conjunction at a signaling complex. IAPs direct both nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 2 (NOD2) signaling complexes and cell death mechanisms to appropriately regulate inflammation. Although it is known that XIAP is critical for NOD2 signaling and that the loss of cIAP1 and cIAP2 blunts NOD2 activity, it is unclear whether these three highly related proteins can compensate for one another in NOD2 signaling or in mechanisms governing apoptosis or necroptosis. This potential redundancy is critically important, given that genetic loss of XIAP causes both very early onset inflammatory bowel disease and X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome 2 (XLP-2) and that the overexpression of cIAP1 and cIAP2 is linked to both carcinogenesis and chemotherapeutic resistance. Given the therapeutic interest in IAP inhibition and the potential toxicities associated with disruption of inflammatory homeostasis, we used synthetic biology techniques to examine the functional redundancies of key domains in the IAPs. From this analysis, we defined the features of the IAPs that enable them to function at overlapping signaling complexes but remain independent and functionally exclusive in their roles as E3 ubiquitin ligases in innate immune and inflammatory signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Since its original discovery in 1993 by Crook et al. (1), the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family of proteins has been the subject of intense scrutiny. Conserved across a wide variety of species (2), the mammalian family of IAP proteins was originally described and understood for its role in preventing cell death (3–5). Since then, the three most widely studied IAP proteins X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP), cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 1 (cIAP1), and cIAP2 have been revealed as crucial E3 ubiquitin ligases of the innate immune system, controlling cellular and organismal responses to pathogens (6, 7), most prominently through tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 1 (NOD1) and NOD2 signaling.

The roles of the IAP proteins in NOD signaling have been controversial. A genetic study suggests that cIAP1 and cIAP2 are essential for NOD activity (8), although this study has the caveat that genetic deletion of cIAP1 also deleted the gene encoding caspase-11 (9). Other studies suggest that all of the IAPs can ubiquitylate all members of the receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK) family (10) and that the loss of cIAP1 partially, but not completely, abrogates NOD-driven cytokine release (11). Despite these findings, human genetic evidence suggests that XIAP is the key driver of NOD signaling (12, 13). XIAP is genetically lost in the inflammatory diseases X-linked lymphoproliferative disorder 2 (XLP2) and very early onset inflammatory bowel disease (VEO-IBD), and patients with mutations in the BIR2 domain of XIAP or patients with deletion mutations in XIAP show defective NOD2 signaling (14–19). Despite this, careful genetic dissection has shown that not all XLP-2 or VEO-IBD mutations cause NOD2 signaling defects (20) and that, while complete XIAP genetic loss ablates NOD2 activation, modest NOD2 activity remains after loss of cIAP1 or cIAP2 and is only markedly blunted upon loss of both (8, 11). Given these somewhat contradictory findings, it remains unknown whether loss of a single IAP protein can be compensated for by the presence of increased abundance of one of the other family members or whether individual domains of the IAPs are driving signal transduction specificity.

In addition to their role at the NOD2 signaling complex, as originally described, XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 each participates in restricting cell death. XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 are known to be critical regulators of diverse cell death programs initiated by the RIPKs (21–26). The importance of intact inhibition of these cell death programs is evident when they are lost genetically, resulting in embryonic lethality and severe organismal dysfunction (21, 27–29). As with IAP function at the NOD2 complex, it remains unknown whether alternate expression of one IAP can compensate for loss of another within these signaling pathways. Furthermore, given the emerging interest in pharmacologically targeting the RIPK family (30), the NOD2 signaling complex (31–33), and a long-standing interest in IAP inhibition in cancer chemotherapy (27, 28, 34, 35), understanding the interdependence of IAP protein activity and whether their functions within the NOD2 signaling pathway can be separated from their roles in inhibiting cell death remains a central question in IAP biology. To address these questions, we generated a genetically isolated set of IAP-knockout cell lines using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) and reconstituted the cells with native or chimeric IAP proteins, which revealed redundant and unique functions among the proteins and that the inability to completely separate IAP activity at the NOD2 complex from IAP-mediated inhibition of cell death contributes to inflammatory pathogenesis.

RESULTS

At least one IAP protein is required for cell survival

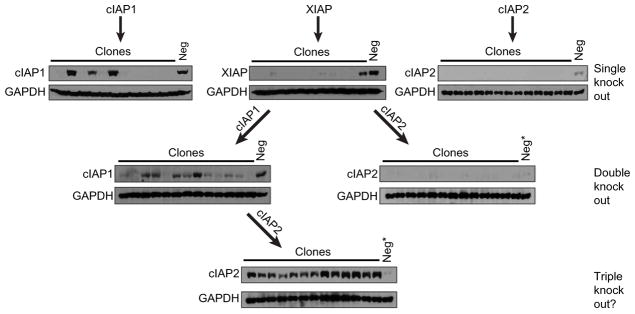

Given the findings suggesting that XIAP is required for optimal NOD2 signaling and that the related IAPs, cIAP1 and cIAP2, have some redundancy in NOD2 signaling (8, 10–13), we wanted to investigate IAP protein function in a genetically isolated setting. To this end, we attempted to generate single, double, and triple knockouts of the three IAP proteins—XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2—using a lentiviral CRISPR/Cas9 system (36). After transduction of HT29 cells with lentivirus carrying single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting cIAP1 (Fig. 1, upper left), XIAP (Fig. 1, upper middle), or cIAP2 (Fig. 1, upper right), individual clones that displayed markedly reduced or complete absence of the targeted IAP protein were detected in a significant proportion of tested clones [IAP1 (9 of 12 clones), XIAP (10 of 11 clones), and cIAP2 (13 of 13 clones) (Fig. 1, “single knockout”)]. This high rate of individual IAP loss indicated that cells could readily tolerate the loss of a single IAP protein family member. We next wanted to test whether the loss of two IAP proteins would be similarly well tolerated. To generate double knockouts, we pooled cells with undetectable XIAP protein to generate a stable knockout XIAP cell line. This XIAP-knockout line was then stably infected with lentivirus targeting either cIAP1 or cIAP2 [Fig. 1, “double knockout” (left and right, respectively)]. Although the efficiency of genetically disrupting the abundance of a second IAP protein was slightly decreased, clones exhibiting substantially decreased or undetectable protein of the second targeted IAP were readily detected—XIAP/cIAP1 (8 of 13 clones) and XIAP/cIAP2 (8 of 13 clones). To then generate a triple-knockout cell line, we pooled cells lacking detectable XIAP and cIAP1 to produce a stable cell line with undetectable XIAP and cIAP1 protein. This double-knockout cell line was then stably transduced with lentivirus containing sgRNA targeting cIAP2. To our surprise, no clones that exhibited even a modest reduction in cIAP2 abundance relative to a parental nontargeted control line were detected. On the contrary, all tested clones exhibited substantially increased cIAP2 as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 1, “triple knockout”). This result suggests that XIAP and cIAP1 regulate cIAP2 posttranscriptionally, each capable of maintaining low cIAP2 protein abundance. More broadly, given that previous results in whole-body knockout mice required isolation of IAP-null cells from embryonic livers or lineage restriction of IAP loss in combination with TNF inhibition (21, 29), our results strongly suggest that at least one of three IAP proteins—XIAP, cIAP1, or cIAP2—is required for cell survival.

Fig. 1. Attempts to generate triple IAP-knockout cells are unsuccessful and result in up-regulation of the remaining IAP protein.

HT29 cells were stably transduced with CRISPR/Cas9 constructs targeting either cIAP1, XIAP, or cIAP2 to generate single-, double-, or triple-knockout cell lines as indicated. Single and double IAP knockouts were readily detected (top and middle), but no triple knockouts were detected (“?”, bottom). Neg, nontargeted CRISPR/Cas9 control; Neg*, the same CRISPR/Cas9 cell line was used as a Western blot control in the right double-knockout blot and the triple-knockout blot. Single-knockout: cIAP1, n = 12 clones; XIAP, n = 11 clones; and cIAP2, n = 13 clones. Double-knockout: XIAP/cIAP1, n = 13 clones and XIAP/cIAP2, n = 13 clones. Triple knockout, n = clones.

cIAP1 and cIAP2 cannot sustain nuclear factor κ B activity when XIAP is genetically lost

Given that cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP function collectively in a number of convergent innate signaling pathways (8, 11–13, 21–24, 29, 37, 38) and that expression of at least one of these three IAP proteins appears to be required for cell (Fig. 1, triple knockout) and organismal survival (21, 29), we hypothesized that, when a single IAP protein is absent, the other two IAP proteins are able to compensate, recovering functional activity at signaling complexes known to use the absent IAP protein. In addition to our findings above, this is suggested by the literature in which small interfering RNA–mediated knockdown of cIAP1 resulted in a partial loss of NOD2 signaling, chemical inhibition of cIAP1-blunted NOD2 responses, and mouse genetic systems where cIAP1 or cIAP2 genetic loss resulted in a dramatic loss of NOD2 signaling (8, 11). Because genetic loss of XIAP is an important mediator of both VEO-IBD and XLP-2 and presents with a wide range manifestations across a broad age range (14–18, 39, 40), we hypothesized that this varied presentation may be accounted for by variable compensation by another IAP family member. Therefore, we chose to initially test whether stable increased abundance of cIAP1 or cIAP2 could functionally recover NOD2 signaling to nuclear factor κ B (NF-κB) and restrict the TNF-induced cell death that is lost with genetic XIAP deletion.

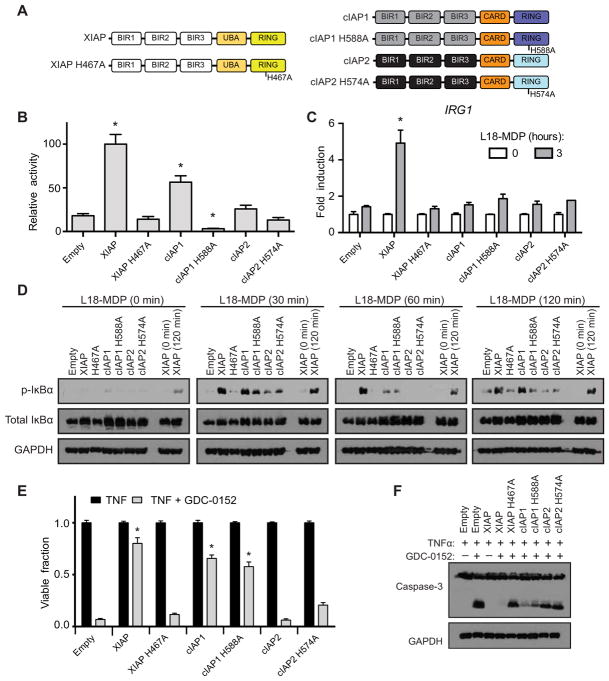

To answer this question, we used a lentiviral construct recently developed in our laboratory, which produces XIAP at near-endogenous abundance (20, 41). XIAP-knockout human embryonic kidney–293T (HEK293T) cells, immortalized bone marrow–derived macrophage (iBMDM), and DC2.4 cell lines were transduced with a lentiviral construct containing cassettes for myc-tagged XIAP, cIAP1, cIAP2, or their respective E3 ligase inactive variants (Fig. 2A and fig. S1, A to C). The manipulated HEK293T cells (fig. S1A) were then examined for their ability to compensate for XIAP loss and coordinate NOD2 signaling by overexpressing hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged NOD2 in the presence of an NF-κB–driven firefly luciferase. XIAP-knockout HEK293T cells reconstituted with wild-type (WT) XIAP displayed significantly increased luciferase activity that was blunted with loss of E3 ligase activity (XIAP H467A). Notably, XIAP-knockout HEK293T cells stably expressing cIAP1 were able to increase luciferase activity significantly above that of the empty vector–reconstituted line in response to NOD2 overexpression in an E3 ligase–dependent manner. HEK293T cells expressing cIAP2 or ligase-deficient cIAP2 H574A could not significantly increase luciferase activity above the empty vector–reconstituted XIAP-knockout cell line in response to NOD2 overexpression (Fig. 2B and fig. S1D for transfection control Western blot). To then determine whether recovery of NOD2-induced NF-κB activity could be elicited by stimulation of endogenous NOD2, DC2.4 cells stably expressing WT XIAP, cIAP1, cIAP2, or their respective ligase-deficient variants (fig. S1B) were stimulated with L18-MDP for 3 hours, and the expression of the NOD2-responsive NF-κB–driven gene IRG1 was analyzed. In contrast to the overexpression luciferase assay, only WT XIAP was able to support L18-MDP–induced NOD2 activation of IRG1 expression significantly above the empty vector–reconstituted control line (Fig. 2C). We have previously identified IRG1 as a reproducible and specific transcript induced upon NOD2 activation (31). To confirm IRG1 as a reliable transcript induced upon NOD2 activation in the DC2.4 cell lines used throughout the work presented here, expression of IL6 was also examined and found to match the IRG1 expression pattern, facilitating the use of IRG1 as a specific readout of NOD2-induced transcriptional activity (fig. S2). Similarly, after confirming that L18-MDP–induced signaling was markedly blunted in the XIAP-knockout iBMDM cells (fig. S3), XIAP-knockout iBMDM cells reconstituted with the native and ligase-deficient IAP proteins (fig. S1C) showed robust and sustained phosphorylation of NF-κB inhibitor α (IκBα) only in the presence of WT XIAP. Both cIAP1 and cIAP2 could initiate phosphorylation of IκBα but were unable to maintain sustained IκBα phosphorylation at all time points (Fig. 2D). This suggests a partial redundancy at the initiation stage but not at the sustained activity stage.

Fig. 2. cIAP1 and cIAP2 cannot fully compensate for XIAP loss.

(A) Schematic of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 proteins reconstituted to XIAP-knockout cell lines. (B) Relative NOD2-activated NF-κB–driven luciferase activity in HEK293T cells reconstituted with the indicated IAP protein. Relative activity normalized to an XIAP activity of 100. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 6 experimental replicates performed on different days. (C) IRG1 expression assayed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in DC2.4 XIAP–knockout cells reconstituted with empty vector or the indicated IAP protein after stimulation with L18-MDP (10 μg/ml) for 3 hours. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty 3-hour time point by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 3 experimental replicates performed on different days. (D) iBMDM XIAP–knockout cell lines re-constituted with the indicated IAP proteins were stimulated with L18-MDP (10 μg/ml) for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min. Cellular lysates were examined by Western blot for NF-κB signaling using the indicated antibodies. Lysates from XIAP at the 0- and 120-min time points of stimulation are included on all blots for comparison. Representative blots from one of three separate experiments are shown. (E) XIAP-knockout iBMDM cells reconstituted with the indicated IAP protein were treated with TNF (10 ng/ml) or TNF (10 ng/ml) and GDC-0152 (200 nM) for 24 hours, and cell viability was quantified by methylene blue staining. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty TNF + GDC-0152 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 3 experimental replicates performed on different days. (F) iBMDM XIAP–knockout cells reconstituted with the indicated IAP protein were treated with TNF (10 ng/ml) alone or in combination with GDC-0152 (200 nM) as indicated for 8 hours, and cellular lysates were assayed by Western blot for caspase-3 cleavage. Representative blots from one of three separate experiments are shown. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; p-IκBα, phosphorylated IκBα.

It has been difficult to separate XIAP’s role in NOD2 signaling with its role in controlling cell death programs (19, 20, 23, 24). To examine whether cIAP1 or cIAP2 could compensate for XIAP loss and continue to restrict cell death, iBMDM cells expressing cIAP1, cIAP2, or their ligase-deficient variants were stimulated with TNF and the IAP antagonist GDC-0152 to induce apoptosis. After 24 hours of stimulation, cIAP1 but not cIAP2 expression resulted in a significant increase in cell viability that was independent of ligase activity (Fig. 2E). This was confirmed by Western blots, which demonstrated that both cIAP1 and cIAP1-H588A expression in XIAP-knockout iBMDM cells resulted in less caspase-3 cleavage in response to TNF and GDC-0152 stimulation compared to the empty vector–reconstituted line (Fig. 2F). Given that cIAP2 displayed reduced activity in these assays and that it was found in decreased abundance by Western blotting (fig S1, A to C), we assessed expression of the mRNA transcripts for each of the IAP proteins from the lentiviral construct in the iBMDM cell lines using primers specific to the synthetic transcripts expressed from the lentiviral construct. Expression of the mRNA transcript for cIAP2 was not significantly different from the expression of the mRNA transcript for XIAP, indicating that the protein abundance seen by Western blot was determined posttranscriptionally, is unique to the individual IAP proteins, and was not driven by cryptic silencing of lentiviral mRNA expression (fig. S4). This result implies that cIAP2 expression and activity is tightly regulated by posttranscriptional events, either by control of translation or posttranslational mechanisms, and cannot be directly increased by increasing mRNA abundance. In addition, as seen from Fig. 1, its abundance is potentially directly controlled by the combined activity of cIAP1 and XIAP.

Collectively, these findings suggest that there are circumstances under which NOD2 signaling and cell death pathways can be separated. Our data indicate that cIAP1 can partially compensate for XIAP loss both in the cell death arena and partially in NOD2 signaling and are further suggestive that this feature of cIAP1 is not dependent on E3 ligase activity. Notably, whereas cIAP1’s compensation for XIAP at the NOD2 complex requires E3 ligase activity, its compensation in suppressing cell death does not. This could be due to a difference in the biochemical manner in which IAPs inhibit caspase activity, a role for cIAP1 in non-enzymatic scaffolding and protein recruitment or, given that these cell lines still retain endogenous cIAP1 and cIAP2, a complex interaction between ligase-deficient cIAP1 and the native cIAP1 (or cIAP2), promoting increased endogenous cIAP1 or cIAP2 activity. Nonetheless, although neither cIAP1 nor cIAP2 can completely compensate for loss of NOD2 signaling when XIAP is genetically lost, enforced expression of cIAP1 can partially compensate for the increased cell death present in XIAP-knockout cells albeit in an E3 ligase activity–independent manner.

XIAP’s second BIR domain maintains initial, but not sustained, NOD2 signaling

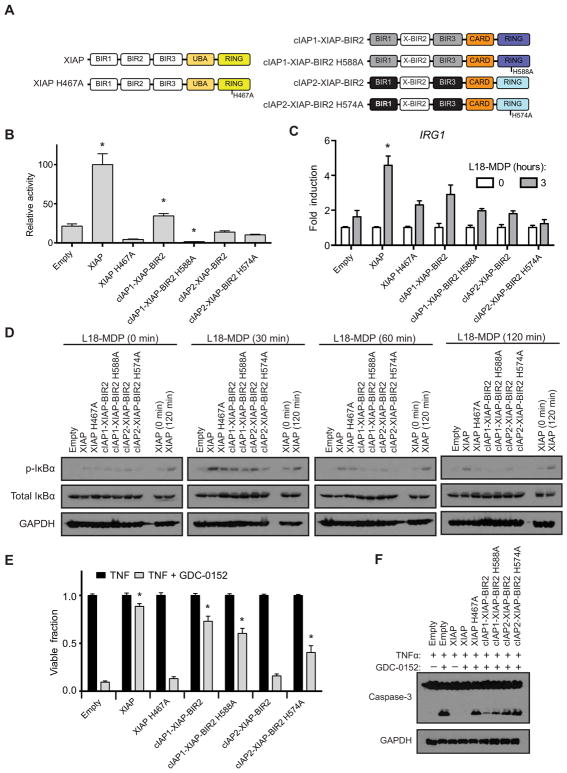

Despite the fact that at least one IAP is required for cell viability (Fig. 1), the results above (Fig. 2) suggest that there are unique features of XIAP that fine tunes cell death and signaling responses, which is not present in cIAP1 nor cIAP2. The second BIR domain of XIAP appears critical for its cellular function to mediate both NOD2 signaling and cell death resistance (12, 13, 15, 19, 20, 42). In addition, XIAP’s second BIR domain critically differentiates it from cIAP1 and cIAP2 by aiding in the direct inhibition of capase-3, capase-7, and capase-9 (42–47). Thus, the second BIR domain of XIAP relative to the BIR domains of cIAP1 and cIAP2 appears to be a uniquely functioning unit. To formally test whether the second BIR domain confers unique functionality to XIAP, we replaced the second BIR domain of cIAP1 and cIAP2 with that of XIAP (Fig. 3A). We then stably expressed these chimeric cIAP1 and cIAP2 proteins in XIAP-knockout cells to determine whether they could compensate for the loss of XIAP (fig. S5, A to C). Overexpression of HA-tagged NOD2 in the presence of a NF-κB–driven luciferase demonstrated that WT XIAP and cIAP1 containing XIAP’s BIR2 domain were capable of coordinating NOD2-induced activation of NF-κB–driven transcription significantly above that of the empty vector–reconstituted line in an E3 ligase–dependent manner (Fig. 3B and fig. S5D). Similar to results with the native IAP proteins, only WT XIAP was capable of coordinating L18-MDP–induced transcription of IRG1 significantly above that of the empty vector–reconstituted line after 3 hours of treatment (Fig. 3C). Biochemical assessment of signaling showed that L18-MDP–induced phosphorylation of IκBα was induced in all IAPs that contained the XIAP BIR2 domain; however, this signaling was only sustained long-term in iBMDMs that stably expressed WT XIAP (Fig. 3D). Only the cIAP1 chimeric protein and its ligase-deficient variant were capable of limiting cell death elicited by the loss of XIAP when examined for both cell viability (Fig. 3E) and caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 3F). These findings suggest that the BIR2 domain of XIAP is not the only required domain for NOD2 signaling, and its presence is not sufficient to confer new activity to cIAP1 and cIAP2. Although either cIAP1 or cIAP1 containing XIAP’s second BIR2 domain could support NF-κB–driven transcription when NOD2 was overexpressed and could coordinate L18-MDP–induced phosphorylation of IκBα, their inability to facilitate L18-MDP–induced transcription of IRG1 indicates that specific functions of XIAP at the NOD2 complex cannot be recovered by either other IAPs or simply by the activity of XIAP’s second BIR domain. However, when coupled to the results described above (Fig. 2), these results further support an E3 ligase–independent, shared cell death resistance phenotype between cIAP1 and XIAP.

Fig. 3. cIAP1 carrying XIAP’s BIR2 domain can partially compensate for XIAP loss.

(A) Schematic of XIAP and cIAP1 and cIAP2 chimeric proteins in which the BIR2 of the native cIAP was replaced with the BIR2 domain of XIAP (X-BIR2). (B) HEK293T cells reconstituted with XIAP or a cIAP1/2 chimeric protein were assayed for relative NF-κB luciferase activity in response to NOD2 overexpression. Relative units were normalized to an XIAP activity of 100. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 6 experimental replicates performed on different days. (C) DC2.4 XIAP–knockout cell line reconstituted with the indicated IAP variant was assayed for IRG1 expression by real-time qPCR after stimulation with L18-MDP (10 μg/ml) for 3 hours. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty 3-hour time point by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 3 experimental replicates performed on different days. (D) After L18-MDP (10 μg/ml) treatment for 0, 30, 60, or 120 min, cellular lysates from iBMDM cells reconstituted with the indicated IAP variants were examined for NF-κB signaling by Western blot using the indicated antibodies. Lysates from XIAP at the 0- and 120-min time points of stimulation are included on all blots for comparison. Representative blots from one of three separate experiments are shown. (E) XIAP or cIAP1/2 chimeric proteins expressed in XIAP-knockout iBMDM cells were assayed for their ability to suppress cell death after TNF (10 ng/ml) or TNF and GDC-0152 (200 nM) stimulation. After 24 hours of treatment, cell viability was assayed by methylene blue staining. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty TNF + GDC-0152 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 3 experimental replicates performed on different days. (F) Cell lysates from iBMDM cells stimulated with TNF (10 ng/ml) and GDC-0152 (200 nM) as indicated for 8 hours were assayed by Western blot for caspase-3 cleavage. Representative blots from one of three separate experiments are shown.

The complete BIR domain architecture works in concert with a functionally redundant RING domain to confer unique IAP protein activity

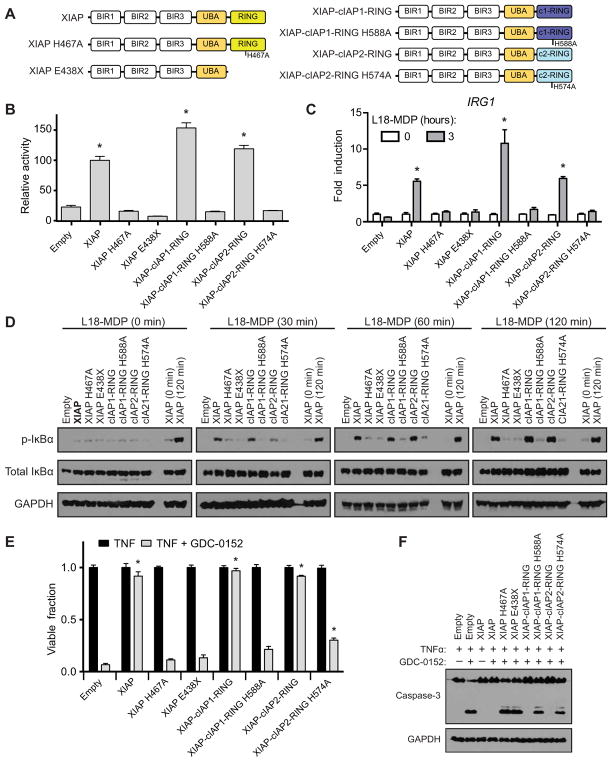

Because XIAP’s second BIR domain was incapable of conferring XIAP’s complete functionality on cIAP1 and cIAP2, we hypothesized that the three BIR domains of the IAP proteins function as a collective unit, conferring unique activity to each protein. This is supported by data indicating that mutation to a single BIR domain (15, 19, 20) and SMAC mimetic compounds that bind only a single BIR domain of an IAP protein impairs near-complete protein function (28, 48–50). Furthermore, the high degree of sequence homology and near-identical structural homology of the RING domains of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 (fig. S6, A and B), and the fact that they all conjugate ubiquitin to the RIPKs (10), supports the notion that the RING domains may be functionally redundant and only exert IAP specific effects when coupled to a unique set of BIR domains.

To examine whether the RING domains perform convergent function that could be transferred from one IAP to another, we generated a set of constructs in which the RING domain of XIAP was either deleted (XIAP E438X) or replaced by the RING domain of cIAP1 (XIAP-cIAP1-RING) or cIAP2 (XIAP-cIAP2-RING). As described above, WT XIAP, ligase-deficient XIAP, and XIAP RING chimeric proteins (Fig. 4A) were expressed in XIAP-knockout cells (fig. S7, A to C), and the ability of these proteins to rescue XIAP function was examined. HEK293T cells expressing XIAP and variants (fig. S7A) were transfected with HA-tagged NOD2 and a NF-κB–driven luciferase reporter construct. Each XIAP protein with a functional RING domain was capable of coordinating NF-κB activity in response to NOD2 significantly above the empty reconstitution cell line. Notably, XIAP-cIAP1-RING and XIAP-cIAP2-RING were both able to activate NF-κB comparable to WT XIAP, and this activity was dependent on RING E3 ligase activity, given that their respective ligase-deficient mutants were incapable of coordinating NF-κB activity above that of the empty vector–reconstituted cell line (Fig. 4B and fig. S7D). The ability of chimeric XIAP proteins harboring cIAP1’s or cIAP2’s RING domain to coordinate NOD2 was further confirmed in XIAP-knockout DC2.4 cells stably expressing the chimeric proteins (fig. S7B). After stimulation with L18-MDP for 3 hours, mRNA was isolated, and induction of IRG1 expression was assessed by real-time qPCR. As was seen in the luciferase assay, XIAP, XIAP-cIAP1-RING, and XIAP-cIAP2-RING each efficiently coordinated transcription of the NOD2 target gene IRG1 (Fig. 4C). This was further tested by signaling experiments performed in iBMDM cells similarly reconstituted with the XIAP RING chimeric proteins (fig. S7C). After stimulation with L18-MDP for 0, 30, 60, or 120 min, the RING chimeric proteins were able to coordinate a sustained increase in the abundance of phosphorylated IκBα comparable to that promoted by WT XIAP (Fig. 4D). To determine whether the XIAP RING-chimeric proteins also had the capacity to restrict TNF-induced cell death, iBMDM cells were stimulated with TNF and GDC-0152 to induce apoptosis. After 24 hours of treatment, XIAP-cIAP1-RING and XIAP-cIAP2-RING each restricted cell death as efficiently as WT XIAP (Fig. 4E). The ability of the RING chimeric proteins to suppress cell death was congruent with their capacity to restrict caspase-3 cleavage in a RING catalytic-dependent manner, as each ligase-deficient RING chimeric protein displayed an inability to restrict cell death and caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 4, E and F). To further confirm that this was not a cell type–specific phenomenon, the XIAP-knockout HT29 cell line was reconstituted with the XIAP RING variants (fig. S8A) and then examined for their capacity to suppress cell death and restrict caspase-3 cleavage. In agreement with XIAP RING variant activity in iBMDM cells, HT29 cells harboring XIAP-cIAP1-RING and XIAP-cIAP2-RING suppressed cell death (fig. S8B) and restricted caspase-3 cleavage (fig. S8C) as efficiently as WT. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the RING domain of cIAP1 and cIAP2 is each capable of replacing the catalytic capacity of the native XIAP RING domain.

Fig. 4. The IAP RING domains of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 are functionally redundant.

(A) Schematic of XIAP and XIAP chimeric proteins containing the RING domain from either cIAP1 or cIAP2. (B) Relative NF-κB–driven luciferase activity after NOD2 overexpression in HEK293T cells reconstituted with the indicated XIAP protein variant. Relative units were normalized to an XIAP activity of 100. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 6 experimental replicates performed on different days. (C) DC2.4 XIAP–knockout cells reconstituted with empty vector or the indicated XIAP protein stimulated with L18-MDP (10 μg/ml) for 3 hours and assayed for the expression of IRG1 by real-time qPCR. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty 3-hour time point by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 3 experimental replicates performed on different days. (D) iBMDM XIAP–knockout cell lines reconstituted with the indicated XIAP variants were stimulated with L18-MDP (10 μg/ml) for 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, and cellular lysates were examined for NF-κB signaling with the indicated antibodies. Representative blots from one of three separate experiments are shown. (E) iBMDM cells reconstituted with the indicated XIAP variants were stimulated with TNF (10 ng/ml) or TNF and GDC-0152 (200 nM) for 24 hours, and cell viability was quantified by methylene blue staining. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to empty TNF + GDC-0152 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 3 experimental replicates performed on different days. (F) After stimulation with TNF (10 ng/ml) and GDC-0152 (200 nM) as indicated for 8 hours, cellular lysates were examined for induction of apoptosis by Western blot for caspase-3. Representative blots from one of three separate experiments are shown.

DISCUSSION

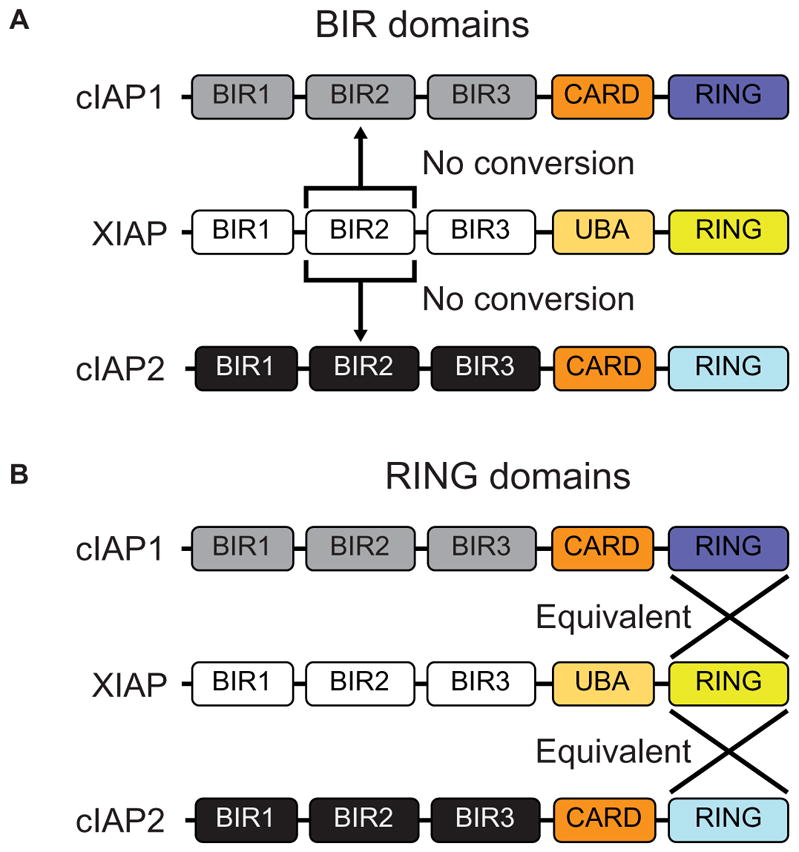

Our findings answer several outstanding questions regarding IAP function at critical innate signaling complexes and provide fresh insight into the roles of IAP protein domains. It demonstrates that, while XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 all play a role in NOD2 signaling (8, 11–13), they do not serve identical functions because only cIAP1 can partially recover XIAP function. Consistent with previous findings (20), it highlights the interconnected nature of IAP function in NOD2 complex activation and cell death inhibition, because separation was only partially achieved with loss of XIAP and stable expression of either cIAP1 or ligase-deficient cIAP1. Furthermore, given that introduction of XIAP’s second BIR domain preserved cell death inhibition by cIAP1 and did not markedly alter its capacity to coordinate NOD2 activity, it is likely that the complete BIR domain architecture and other protein scaffolding domains in the IAP proteins, such as the UBA and CARD domains, and not the RING domains facilitate their unique activity in NOD2 coordination and cell death inhibition. This is further substantiated by the results presented here that demonstrate the interchangeable nature of the IAP RING domains.

Collectively, the data presented here provide strong evidence that the major determinant of unique IAP protein function is established not by the RING domain but rather by the triplet of BIR domains within each IAP protein. Although the data here cannot rule out that other domains, such as the UBA and CARD domains, within the IAP proteins also play a critical role, it makes a compelling case as to the critical importance and distinct nature of the BIR domains. Because complete XIAP function is only restored when XIAP’s complete set of three BIR domains is transferred to cIAP1’s or cIAP2’s RING domain, it is likely that the three BIR domains of an IAP protein function as a unit to differentiate activity of the redundant RING domain in concert with other scaffolding and protein-protein interaction domains (Fig. 5). This is supported by our finding of the high degree of sequence and structure homology of the three RING domains, the previously reported mechanism of ubiquitin transfer by the RING domain (51, 52), and our findings that all of the IAP RING domains coupled to XIAP’s set of BIR domains function equivalently at the NOD2 complex and at cell death inhibition. This insight also has implications for the broad and growing interest in pharmacologically targeting signaling from the NOD2 complex and the IAP family of proteins. By detailing the nature of the IAP protein domain functions, it provides evidence that disruption of individual IAP proteins will only be achieved by a SMAC mimetic that orthogonally disrupts an individual IAP protein’s BIR domains and that this is likely to disrupt all of that IAP protein’s function.

Fig. 5. Schematic demonstrating the unique and redundant functional domains of the IAP proteins.

(A) Swapping XIAP’s BIR2 domain into cIAP1 or cIAP2 results in no conversion of protein function. (B) Interchange of the RING domains of cIAP1 and cIAP2 with XIAP results in proteins with equivalent function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, cells, and reagents

Immortalized murine BMDMs, originally from E. Latz (University of Bonn, Institute of Innate Immunity), were cultured as described (53). DC2.4 dendritic cells were obtained from K. Rock under approved material transfer agreement (Department of Pathology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA) and cultured as previously described (20). XIAP, cIAP1, cIAP2, and all chimeric proteins were cloned by Gibson method (54) to a lentiviral expression plasmid (41) and virus produced in HEK293T cells with cotransfection of pMD2.G (Addgene plasmid #12259) and PsPax2 (Addgene plasmid #12260), gifts from D. Trono. LentiCrispV2 was a gift from F. Zhang (Addgene plasmid #52961). pcDNA3-HA-NOD2 was a gift from C. McDonald (Department of Pathology, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH). Luciferase reporter assays were recorded on a Wallac Victor3V (PerkinElmer) using a Dual Luciferase Reporter kit (Promega). For Western blotting, proteins were detected using mouse monoclonal antibody for XIAP (BD Transduction Laboratories), mouse monoclonal antibody for OmniProbe (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse polyclonal antibody for GAPDH (ProteinTech), mouse monoclonal antibody for HA-tag (BioLegend), rabbit monoclonal antibody for myc-tag, rabbit polyclonal antibody for IκBα, mouse monoclonal antibody for phosphorylated IκBα, and rabbit polyclonal antibody for caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology) and were used as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell death, quantitative reverse transcription PCR, and signaling assays

For cell death assays, after stimulation with TNF (Gold Biotechnology) and GDC-0152 (MedChem Express) for the times indicated, plates were stained with methylene blue (2 mg/ml) and were scanned (Brother MFC-J4510DW) for quantification in ImageJ. L18-MDP (Invivogen) was used for stimulation of cells in quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) and signaling assays. After extraction of mRNA and cDNA synthesis using QiaShredder, RNEasy kits, and Quantitect kits (QIAGEN), qRT-PCR was performed using primers directed to GAPDH (forward: 5′-AGGCCGGTGCTGAGTATGTC-3′; reverse: 5′-TGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCT-3′) and IRG1 (forward: 5′-GTTTGGGGTCGACCAGACTT-3′; reverse: 5′-CAGGTCGA-GGCCAGAAAACT-3′), IAPs using the common forward primer P2A-F (forward: 5′-AGATCCATTGTGCTGGATCTAC-3′), and IAP-specific reverse primers XIAP-R (reverse: 5′-TGATGTCTGC-AGGTACACAAG-3′), cIAP1-R (reverse: 5′-TCGTGCTATCTTC-CATTATACTCTT-3′), and cIAP2-R (reverse: 5′-CAAACGTGTT-GGCGCTTT-3′) with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Unless otherwise indicated, all experiments were performed a minimum of three separate times, error bars represent SEM, and statistical analysis was performed using Prism (GraphPad). For signaling experiments, cells were treated with L18-MDP (10 μg/ml; Invivogen) for the indicated times. Five minutes before on-plate lysis and harvest with complete Triton X-100 lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology), cells were treated with 0.1 μM calyculin A (Cell Signaling Technology) and probed with the indicated antibody.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 in XIAP-knockout cell lines.

Fig. S2. L18-MDP–induced NOD2-driven IL6 expression in DC2.4 cell lines.

Fig. S3. L18-MDP–induced NOD2 signaling to NF-κB in XIAP-knockout iBMDM cells.

Fig. S4. Real-time qPCR of virally expressed XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2.

Fig. S5. XIAP, cIAP1-XIAP-BIR2, and cIAP2-XIAP-BIR2 in XIAP-knockout cell lines.

Fig. S6. Sequence and structure comparison of the RING domains of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2.

Fig. S7. XIAP, XIAP-cIAP1-RING, and XIAP-cIAP2-RING in XIAP-knockout cell lines.

Fig. S8. Reconstitution of XIAP-knockout HT29 cells with XIAP RING swap variants suppresses cell death.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank G. R. Dubyak, P. Ramakrishnan, T. Xiao, C. McDonald, X. Li, F. Cominelli, and T. Pizarro for critical input and feedback on the manuscript.

Funding: This manuscript was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 GM086550 and P01 DK091222) awarded to D.W.A. S.M.C. was supported by the Case Western Reserve University NIH Medical Scientist Training Program (T32 GM007250) and the Case Western Reserve University Immunology Training Program (T32 AI089474). J.K.R was supported by the Case Western Reserve University NIH Medical Scientist Training Program (T32 GM007250).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Crook NE, Clem RJ, Miller LK. An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J Virol. 1993;67:2168–2174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2168-2174.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uren AG, Coulson EJ, Vaux DL. Conservation of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis repeat proteins (BIRPs) in viruses, nematodes, vertebrates and yeasts. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duckett CS, Nava VE, Gedrich RW, Clem RJ, Van Dongen JL, Gilfillan MC, Shiels H, Hardwick JM, Thompson CB. A conserved family of cellular genes related to the baculovirus iap gene and encoding apoptosis inhibitors. EMBO J. 1996;15:2685–2694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature. 1997;388:300–304. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvesen GS, Duckett CS. IAP proteins: Blocking the road to death’s door. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrm830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandenabeele P, Bertrand MJM. The role of the IAP E3 ubiquitin ligases in regulating pattern-recognition receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:833–844. doi: 10.1038/nri3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galbán S, Duckett CS. XIAP as a ubiquitin ligase in cellular signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:54–60. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertrand MJM, Doiron K, Labbé K, Korneluk RG, Barker PA, Saleh M. Cellular inhibitors of apoptosis cIAP1 and cIAP2 are required for innate immunity signaling by the pattern recognition receptors NOD1 and NOD2. Immunity. 2009;30:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenneth NS, Younger JM, Hughes ED, Marcotte D, Barker PA, Saunders TL, Duckett CS. An inactivating caspase 11 passenger mutation originating from the 129 murine strain in mice targeted for c-IAP1. Biochem J. 2012;443:355–359. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertrand MJM, Lippens S, Staes A, Gilbert B, Roelandt R, De Medts J, Gevaert K, Declercq W, Vandenabeele P. cIAP1/2 are direct E3 ligases conjugating diverse types of ubiquitin chains to receptor interacting proteins kinases 1 to 4 (RIP1-4) PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e22356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tigno-Aranjuez JT, Bai X, Abbott DW. A discrete ubiquitin-mediated network regulates the strength of NOD2 signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:146–158. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01049-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieg A, Correa RG, Garrison JB, Le Negrate G, Welsh K, Huang Z, Knoefel WT, Reed JC. XIAP mediates NOD signaling via interaction with RIP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14524–14529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907131106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damgaard RB, Nachbur U, Yabal M, Wong WWL, Fiil BK, Kastirr M, Rieser E, Rickard JA, Bankovacki A, Peschel C, Ruland J, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N, Kaufmann T, Strasser A, Walczak H, Silke J, Jost PJ, Gyrd-Hansen M. The ubiquitin ligase XIAP recruits LUBAC for NOD2 signaling in inflammation and innate immunity. Mol Cell. 2012;46:746–758. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigaud S, Fondanèche MC, Lambert N, Pasquier B, Mateo V, Soulas P, Galicier L, Le Deist F, Rieux-Laucat F, Revy P, Fischer A, de Saint Basile G, Latour S. XIAP deficiency in humans causes an X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature05257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Worthey EA, Mayer AN, Syverson GD, Helbling D, Bonacci BB, Decker B, Serpe JM, Dasu T, Tschannen MR, Veith RL, Basehore MJ, Broeckel U, Tomita-Mitchell A, Arca MJ, Casper JT, Margolis DA, Bick DP, Hessner MJ, Routes JM, Verbsky JW, Jacob HJ, Dimmock DP. Making a definitive diagnosis: Successful clinical application of whole exome sequencing in a child with intractable inflammatory bowel disease. Genet Med. 2011;13:255–262. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182088158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsh RA, Madden L, Kitchen BJ, Mody R, McClimon B, Jordan MB, Bleesing JJ, Zhang K, Filipovich AH. XIAP deficiency: A unique primary immunodeficiency best classified as X-linked familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and not as X-linked lymphoproliferative disease. Blood. 2010;116:1079–1082. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-256099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeissig Y, Petersen BS, Milutinovic S, Bosse E, Mayr G, Peuker K, Hartwig J, Keller A, Kohl M, Laass MW, Billmann-Born S, Brandau H, Feller AC, Röcken C, Schrappe M, Rosenstiel P, Reed JC, Schreiber S, Franke A, Zeissig S. XIAP variants in male Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2015;64:66–76. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguilar C, Lenoir C, Lambert N, Bègue B, Brousse N, Canioni D, Berrebi D, Roy M, Gérart S, Chapel H, Schwerd T, Siproudhis L, Schäppi M, Al-Ahmari A, Mori M, Yamaide A, Galicier L, Neven B, Routes J, Uhlig HH, Koletzko S, Patel S, Kanegane H, Picard C, Fischer A, Bensussan NC, Ruemmele F, Hugot JP, Latour S. Characterization of Crohn disease in X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis–deficient male patients and female symptomatic carriers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1131–1141.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damgaard RB, Fiil BK, Speckmann C, Yabal M, zur Stadt U, Bekker-Jensen S, Jost PJ, Ehl S, Mailand N, Gyrd-Hansen M. Disease-causing mutations in the XIAP BIR2 domain impair NOD2-dependent immune signalling. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:1278–1295. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chirieleison SM, Marsh RA, Kumar P, Rathkey JK, Dubyak GR, Abbott DW. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) signaling defects and cell death susceptibility cannot be uncoupled in X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP)-driven inflammatory disease. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:9666–9679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.781500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moulin M, Anderton H, Voss AK, Thomas T, Wong WWL, Bankovacki A, Feltham R, Chau D, Cook WD, Silke J, Vaux DL. IAPs limit activation of RIP kinases by TNF receptor 1 during development. EMBO J. 2012;31:1679–1691. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vince JE, Wong WWL, Gentle I, Lawlor KE, Allam R, O’Reilly L, Mason K, Gross O, Ma S, Guarda G, Anderton H, Castillo R, Häcker G, Silke J, Tschopp J. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins limit RIP3 kinase-dependent interleukin-1 activation. Immunity. 2012;36:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yabal M, Müller N, Adler H, Knies N, Groß CJ, Damgaard RB, Kanegane H, Ringelhan M, Kaufmann T, Heikenwälder M, Strasser A, Groß O, Ruland J, Peschel C, Gyrd-Hansen M, Jost PJ. XIAP restricts TNF- and RIP3-dependent cell death and inflammasome activation. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1796–1808. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawlor KE, Khan N, Mildenhall A, Gerlic M, Croker BA, D’Cruz AA, Hall C, Kaur Spall S, Anderton H, Masters SL, Rashidi M, Wicks IP, Alexander WS, Mitsuuchi Y, Benetatos CA, Condon SM, Wong WW-L, Silke J, Vaux DL, Vince JE. RIPK3 promotes cell death and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the absence of MLKL. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenev T, Bianchi K, Darding M, Broemer M, Langlais C, Wallberg F, Zachariou A, Lopez J, MacFarlane M, Cain K, Meier P. The Ripoptosome a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Mol Cell. 2011;43:432–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Kellert B, Dimitrova DP, Langlais C, Hupe M, Cain K, MacFarlane M, Häcker G, Leverkus M. cIAPs block ripoptosome formation, a RIP1/Caspase-8 containing intracellular cell death complex differentially regulated by cFLIP isoforms. Mol Cell. 2011;43:449–463. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vince JE, Wong WWL, Khan N, Feltham R, Chau D, Ahmed AU, Benetatos CA, Chunduru SK, Condon SM, Mckinlay M, Brink R, Leverkus M, Tergaonkar V, Schneider P, Callus BA, Koentgen F, Vaux DL, Silke J. IAP antagonists target cIAP1 to induce TNFα-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007;131:682–693. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varfolomeev E, Blankenship JW, Wayson SM, Fedorova AV, Kayagaki N, Garg P, Zobel K, Dynek JN, Elliott LO, Wallweber HJA, Flygare JA, Fairbrother WJ, Deshayes K, Dixit VM, Vucic D. IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-κB activation, and TNFα-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007;131:669–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong WWL, Vince JE, Lalaoui N, Lawlor KE, Chau D, Bankovacki A, Anderton H, Metcalf D, O’Reilly L, Jost PJ, Murphy JM, Alexander WS, Strasser A, Vaux DL, Silke J. cIAPs and XIAP regulate myelopoiesis through cytokine production in an RIPK1- and RIPK3-dependent manner. Blood. 2014;123:2562–2572. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-510743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bullock AN, Degterev A. Targeting RIPK1,2,3 to combat inflammation. Oncotarget. 2015;6:34057–34058. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tigno-Aranjuez JT, Benderitter P, Rombouts F, Deroose F, Bai X, Mattioli B, Cominelli F, Pizarro TT, Hoflack J, Abbott DW. In vivo inhibition of RIPK2 kinase alleviates inflammatory disease. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:29651–29664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.591388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canning P, Ruan Q, Schwerd T, Hrdinka M, Maki JL, Saleh D, Suebsuwong C, Ray S, Brennan PE, Cuny GD, Uhlig HH, Gyrd-Hansen M, Degterev A, Bullock AN. Inflammatory signaling by NOD-RIPK2 is inhibited by clinically relevant Type II kinase inhibitors. Chem Biol. 2015;22:1174–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nachbur U, Stafford CA, Bankovacki A, Zhan Y, Lindqvist LM, Fiil BK, Khakham Y, Ko HJ, Sandow JJ, Falk H, Holien JK, Chau D, Hildebrand J, Vince JE, Sharp PP, Webb AI, Jackman KA, Mühlen S, Kennedy CL, Lowes KN, Murphy JM, Gyrd-Hansen M, Parker MW, Hartland EL, Lew AM, Huang DCS, Lessene G, Silke J. A RIPK2 inhibitor delays NOD signalling events yet prevents inflammatory cytokine production. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6442. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L, Thomas RM, Suzuki H, De Brabander JK, Wang X, Harran PG. A small molecule Smac mimic potentiates TRAIL- and TNFα-mediated cell death. Science. 2004;305:1471–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1098231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Almagro MC, Vucic D. The inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins are critical regulators of signaling pathways and targets for anti-cancer therapy. Exp Oncol. 2012;34:200–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods. 2014;11:783–784. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wicki S, Gurzeler U, Wei-Lynn Wong W, Jost PJ, Bachmann D, Kaufmann T. Loss of XIAP facilitates switch to TNFα-induced necroptosis in mouse neutrophils. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2422. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Labbé K, McIntire CR, Doiron K, Leblanc PM, Saleh M. Cellular inhibitors of apoptosis proteins cIAP1 and cIAP2 are required for efficient caspase-1 activation by the inflammasome. Immunity. 2011;35:897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmid JP, Canioni D, Moshous D, Touzot F, Mahlaoui N, Hauck F, Kanegane H, Lopez-Granados E, Mejstrikova E, Pellier I, Galicier L, Galambrun C, Barlogis V, Bordigoni P, Fourmaintraux A, Hamidou M, Dabadie A, Le Deist F, Haerynck F, Ouachée-Chardin M, Rohrlich P, Stephan JL, Lenoir C, Rigaud S, Lambert N, Milili M, Schiff C, Chapel H, Picard C, de Saint Basile G, Blanche S, Fischer A, Latour S. Clinical similarities and differences of patients with X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome type 1 (XLP-1/SAP deficiency) versus type 2 (XLP-2/XIAP deficiency) Blood. 2011;117:1522–1529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-298372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Speckmann C, Lehmberg K, Albert MH, Damgaard RB, Fritsch M, Gyrd-Hansen M, Rensing-Ehl A, Vraetz T, Grimbacher B, Salzer U, Fuchs I, Ufheil H, Belohradsky BH, Hassan A, Cale CM, Elawad M, Strahm B, Schibli S, Lauten M, Kohl M, Meerpohl JJ, Rodeck B, Kolb R, Eberl W, Soerensen J, von Bernuth H, Lorenz M, Schwarz K, zur Stadt U, Ehl S. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) deficiency: The spectrum of presenting manifestations beyond hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Clin Immunol. 2013;149:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chirieleison SM, Kertesy SB, Abbott DW. Synthetic biology reveals the uniqueness of the RIP kinase domain. J Immunol. 2016;196:4291–4297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi R, Deveraux Q, Tamm I, Welsh K, Assa-Munt N, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. A single BIR domain of XIAP sufficient for inhibiting caspases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7787–7790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Y, Park YC, Rich RL, Segal D, Myszka DG, Wu H. Structural basis of caspase inhibition by XIAP: Differential roles of the linker versus the BIR domain. Cell. 2001;104:781–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki Y, Nakabayashi Y, Takahashi R. Ubiquitin-protein ligase activity of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein promotes proteasomal degradation of caspase-3 and enhances its anti-apoptotic effect in Fas-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8662–8667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161506698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riedl SJ, Renatus M, Schwarzenbacher R, Zhou Q, Sun C, Fesik SW, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS. Structural basis for the inhibition of caspase-3 by XIAP. Cell. 2001;104:791–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chai J, Shiozaki E, Srinivasula SM, Wu Q, Datta P, Alnemri ES, Shi Y. Structural basis of caspase-7 inhibition by XIAP. Cell. 2001;104:769–780. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiozaki EN, Chai J, Rigotti DJ, Riedl SJ, Li P, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Fairman R, Shi Y. Mechanism of XIAP-mediated inhibition of caspase-9. Mol Cell. 2003;11:519–527. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lukacs C, Belunis C, Crowther R, Danho W, Gao L, Goggin B, Janson CA, Li S, Remiszewski S, Schutt A, Thakur MK, Singh SK, Swaminathan S, Pandey R, Tyagi R, Gosu R, Kamath AV, Kuglstatter A. The structure of XIAP BIR2: Understanding the selectivity of the BIR domains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:1717–1725. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913016284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cossu F, Malvezzi F, Canevari G, Mastrangelo E, Lecis D, Delia D, Seneci P, Scolastico C, Bolognesi M, Milani M. Recognition of Smac-mimetic compounds by the BIR domain of cIAP1. Protein Sci. 2010;19:2418–2429. doi: 10.1002/pro.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Condon SM, Mitsuuchi Y, Deng Y, LaPorte MG, Rippin SR, Haimowitz T, Alexander MD, Kumar PT, Hendi MS, Lee Y-H, Benetatos CA, Yu G, Kapoor GS, Neiman E, Seipel ME, Burns JM, Graham MA, McKinlay MA, Li X, Wang J, Shi Y, Feltham R, Bettjeman B, Cumming MH, Vince JE, Khan N, Silke J, Day CL, Chunduru SK. Birinapant a Smac-mimetic with improved tolerability for the treatment of solid tumors and hematological malignancies. J Med Chem. 2014;57:3666–3677. doi: 10.1021/jm500176w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Budhidarmo R, Nakatani Y, Day CL. RINGs hold the key to ubiquitin transfer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakatani Y, Kleffmann T, Linke K, Condon SM, Hinds MG, Day CL. Regulation of ubiquitin transfer by XIAP, a dimeric RING E3 ligase. Biochem J. 2013;450:629–638. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russo HM, Rathkey J, Boyd-Tressler A, Katsnelson MA, Abbott DW, Dubyak GR. Active caspase-1 induces plasma membrane pores that precede pyroptotic lysis and are blocked by lanthanides. J Immunol. 2016;197:1353–1367. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison C, III, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 in XIAP-knockout cell lines.

Fig. S2. L18-MDP–induced NOD2-driven IL6 expression in DC2.4 cell lines.

Fig. S3. L18-MDP–induced NOD2 signaling to NF-κB in XIAP-knockout iBMDM cells.

Fig. S4. Real-time qPCR of virally expressed XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2.

Fig. S5. XIAP, cIAP1-XIAP-BIR2, and cIAP2-XIAP-BIR2 in XIAP-knockout cell lines.

Fig. S6. Sequence and structure comparison of the RING domains of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2.

Fig. S7. XIAP, XIAP-cIAP1-RING, and XIAP-cIAP2-RING in XIAP-knockout cell lines.

Fig. S8. Reconstitution of XIAP-knockout HT29 cells with XIAP RING swap variants suppresses cell death.