Abstract

Objective: In Denmark, parents with small children have the highest contact frequency to out-of-hours (OOH) service, but reasons for OOH care use are sparsely investigated. The aim was to explore parental contact pattern to OOH services and to explore parents’ experiences with managing their children’s acute health problems.

Design: A qualitative study was undertaken drawing on a phenomenological approach. We used semi-structured interviews, followed by an inductive content analysis. Nine parents with children below four years of age were recruited from a child day care centre in Aarhus, Denmark for interviews.

Results: Navigation, information, parental worry and parental development appeared to have an impact on OOH services use. The parents found it easy to navigate in the health care system, but they often used the OOH service instead of their own general practitioner (GP) due to more compatible opening hours and insecurity about the urgency of symptoms. When worried about the severity, the parents sought information from e.g. the internet or the health care professionals. The first child caused more worries and insecurity due to less experience with childhood diseases and the contact frequency seemed to decrease with parental development.

Conclusion: Parents’ use of the OOH service is affected by their health literacy levels, e.g. level of information, how easy they find access to their GP, how trustworthy and authorized health information is, as well as how much they worry and their parental experience. These findings must be considered when planning effective health services for young families.

Key points

The main findings are that the parents in our study found it easy to navigate in the healthcare system, but they used the OOH service instead of their own general practitioner, when this suited their needs. The parents sought information from e.g. the internet or the health care professionals when they were worried about the severity of their children’s diseases. They sometimes navigated strategically in the healthcare system by e.g. using the OOH service for reassurance and when it was most convenient according to opening hours. The first child seemed to cause more worries and insecurity due to limited experience with childhood diseases, and parental development seems to decrease contact frequency.

Overall, this study contributes with valuable insights into the understanding of parents’ help seeking behaviour. There seems to be a potential for supporting especially first-time parents in their use of the out of hours services.

Keywords: After hours care, primary health care, health literacy, paediatrics, parents, medical necessity, help-seeking

Background

In many European countries, out-of-hours (OOH) primary care faces high demands, with considerable workload. Many of these contacts are from parents with children between 0 and 4 years of age [1]. Small children are more often ill due to childhood infections, with general symptoms such as fever [2]. Often, general practitioners (GPs) and their patients do not assess severity of disease or symptoms similar [3–5]. A part of contacts from parents are for non-urgent conditions, which could have been managed by their own GP or applied self-care seen from a medical perspective [6]. GPs at the Danish OOH primary care assessed 57-87% of the parents’ contacts to be not severe, depending on the type of contact, while parents perceived these as severe [7].

Qualitative studies have pointed out how parents experience handling a sick child outside the opening hours of their GPs as stressful. The parents worry about dealing with the disease incorrectly, and this concern, combined with factors such as lack of social support and self-confidence, results in the parents calling the OOH primary care [8]. Worrying and need for reassurance are motives frequently mentioned by parents contacting OOH primary care [6], as well as insecurity or a perceived acute or serious illness [8–13]. These findings may present a potential for change in the parents’ perception of severity and the use of the OOH care. Furthermore, it is interesting to explore why the parents use the OOH care instead of their own GP.

As the demands in OOH primary care are high, with frequent contacts for medically non-urgent problems and limited knowledge on help seeking behaviour by parents, more knowledge about the motivation behind their decisions is needed. Such knowledge could potentially identify factors, that could be part of a focused strategy to optimise health care use. Thus, the aim of the study was to explore Danish parents’ experiences with managing their children’s acute health problems focusing on parental contact pattern to OOH services and their navigation in the health care system.

Methods

Design

We conducted a qualitative interview study, inspired by a phenomenological approach, which made it possible to gain insight into in-depth descriptions of parents’ experiences with managing sick children and navigating in the Danish healthcare system.

Setting

The Danish health service is based on the principle of free and equal access to treatment 24/7 [14]. The contact to the health service is divided into daytime care, from 8 am to 4 pm, and OOH care from 4pm to 8am on weekdays, in weekends, and on holidays. In daytime, patients primarily contact their own GP, while OOH care is divided in OOH primary care, the emergency department (ED) and emergency medical service 112 (EMS) [15]. The OOH primary care is an acute care service that can be used in the sudden emergence of disease, exacerbation of a disease or injury. The on-call doctor has, in addition to their medical function, a function as a gatekeeper for the rest of the health care service.

Selection of participants

Inclusion criteria and recruitment

The parents were eligible to participate if they had a child in the age 0–4 years and were brought up with the Danish health care system. The interviewers (ML & CRT) recruited from an integrated day care centre in Aarhus, Denmark. Firstly, an information letter was distributed, and afterwards the parents were contacted directly in the day care centre. Despite being interested in both men and women’s experiences, we only managed to recruit women. The few men who were available to contact suggested that we interviewed their wife, referring to for example maternity leave, indicating better time or the role as primary caretaker.

We contacted 17 parents, of which 15 were interested in participating. Out of these, four were excluded, because their youngest child was older than four years. Two parents resigned from participation, whereby nine parents were included in the study.

The included parents

All the included parents lived in high income residential areas with the fathers of their children. The parents ranged from 27–42 years and had either one or two children. The parents either had or were enrolled in a higher education (see Table 1). Two parents had an education in health care (i.e. nurse and pharmacist). All parents had been in contact with the OOH primary care service on behalf of their children within the last year.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the nine included parents.

| Informant | Age | Civil status | Education/work | Age of children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Pilot) | Early 30’s | Married | Master of Public Health | 3 years |

| B | Late 20’s | Cohabiting | Psychology student | 1,5 & 5 years |

| C | Late 20’s | Cohabiting | Kindergarten teacher | 1,5 years |

| D | Late 20’s | Married | PhD student in mathematics | 5 months & 3 years |

| E | Mid 30’s | Married | Building constructor | 3,5 & 7 years |

| F | Early 40’s | Married | Pianist | 4 & 8 years |

| G | Mid 30’s | Cohabiting | Nurse | 10 months & 3,5 years |

| H | Early 30’s | Married | Bandagist | 8 months & 2,5 years |

| I | Early 30’s | Married | Pharmacist | 1 & 3,5 years |

Data collection

A semi-structured research interview was used to assess specific themes, while allowing parents to communicate freely in their own words about their experiences with sick children and the use of OOH primary care service [16]. Semi-structured interviews made it possible to change the interview guide and the phrasing of the questions during the interview, depending on the informant. The interviews were conducted over a 2-week period in September 2016.

Interviews

Two researchers (ML & CRT) conducted one pilot interview and eight face-to-face semi-structured interviews alternating between the function of interviewer and observer. This constellation allowed the interviewer to concentrate on listening, understanding and asking questions, while the observer wrote notes and supplemented. The interviews, which lasted around 45–60 minutes, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by ML and CRT. The interviews took place either at the parents’ homes or in the day care, depending on the parents' wishes. After each interview, the interview was evaluated by the two researchers and notes from the interview were written down for later use in the analysis.

Data analysis

Phenomenological approach

The interview study was based on a phenomenological approach [17] aiming to describe the phenomenon ‘use of the OOH service’ from the parents’ lifeworld. Thus, the phenomenological perspective allowed us to gain a greater understanding of the life of the parents through subjective experienced descriptions [17], as we examined how parents manage their children’s acute illness and their use of the OOH services. However, phenomenology was not used as a direct research method, but served as a guiding principle for the research process.

Content analysis

The nine interviews were analysed using an inductive content analysis, focusing on the contextual meaning of the parents’ experiences and descriptions. The purpose was to explore the research questions based on data instead of verifying data based on a predetermined theory. Therefore, the parents’ experiences with the OOH service evolved freely from the material rather than from established categories [18]. Prior to the analysis, the interviews were read thoroughly to obtain an overall impression of the material, and additionally the notes from the interviews were used to contextualize the interviews [19].

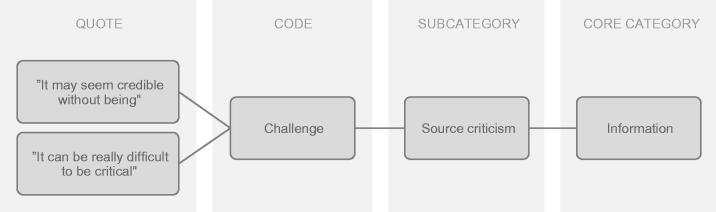

We began with an open coding of the material, followed by the development of subcategories and finally core categories. Initially this process was conducted individually, after which we discussed our different groupings of the codes to subcategories. To validate the coding, each of the two interviewers (ML & CRT) analysed transcripts independently in Nvivo version 11.0, and then resolved any differences by consensus [20]. The work with the analysis was a dialectical interaction between the steps mentioned, before the results were final [19,21]. In the end, the core categories and related subcategories were compared [19]. Each core category consisted of several subcategories which again consisted of many different codes. Figure 1 shows an example of extracting codes based on quotes, transferred to a subcategory and finally a core category.

Figure 1.

Example of coding process from quote to core category.

Results

Four core categories appeared to have an impact on OOH services use by the interviewed parents: navigation, information, parental worry and parental development.

Navigation

In general, the parents we interviewed found it easy to navigate the health care system. They appreciated the possibility of contacting a doctor 24 hours a day, but they all preferred to contact their own GP, if possible. This preference was based upon a familiarity between the GP and the parents as well as the GPs’ access to their medical records.

The parents all described how the significant difference between their own GP and the OOH primary care service is the opening hours. The parents found it easier to access the OOH primary care service than their own GP, since the opening hours of the OOH service are more compatible with the family’s schedule. The majority of the parents were working from 8am to 4pm and were only home with their children during hours, where their own GP practice was closed. The parents participating in this study were also more likely to call the OOH service close to holidays and weekends when their own GP practice was closed for a long time.

I make a judgement whether contact to the doctor can wait for tomorrow, but if we’re close to a weekend, you might as well call the doctor on Friday because you can’t get in touch with your doctor before Monday. (Ida)

However, the parents generally had a clear understanding that a contact to the OOH service compared to their own GP required a more severe and acute health problem. Yet, it could be a challenge for them to decide whether contacting primary care for a health problem that occurs outside office hours can wait until their own GP opens.

Sometimes I think it can be a bit difficult to assess the degree of injury. When is it your own GP or the OOH doctor? (Gitte)

The parents in our study who were working in the health care system considered their work-related experiences to be an advantage in terms of navigation and understanding the system. It gave them easy and direct access to other health care professionals, where they could seek advice. All the parents considered themselves as having an active role when they are in contact with the health service. They found this a necessity in a busy health service. The parents also noticed that not everyone had the resources to be an active navigator in the health care system.

I get involved and search for information and I think you do not necessarily get an answer to everything by contacting one or the other expert or person. I think that you yourself should do something to know what e.g. certain medical examinations are about. (Anne)

Information

In general, the parents we interviewed thought that they had sufficient information about their children’s health and possible diseases. If not, they typically used different information sources, such as the internet, health care professionals and campaigns. Information from e.g. the OOH primary care service or the day care centre was considered as preventive, and sometimes alleviated their need for contacting the health service.

The parents in our study preferred trustworthy information sources and thus only sought information from authorities rather than experience-based knowledge; ‘I’m not so fond of some blog, where 97 worried mothers list which diseases their children do and don’t have’ (Helle). In addition, most of the parents preferred only to seek help within their own network, if a person in the network was health care educated. Furthermore, some of the parents avoided searching on the internet, to not get unnecessarily concerned. While the other parents thought that information helped to create peace of mind and they were therefore actively seeking it; ‘Actually, I mostly “google” it (disease/symptoms)’ (Gitte).

Parental worry

Generally, the parents in our study considered illness as a natural part of childhood where most often children get well without medical treatment. When handling their children’s diseases, the parents used their common sense, and they trusted their own intuition in assessing the severity of the children’s disease. ‘As long as I can make contact with the children, they want something to drink and eat, and if they play, I’m not worried at all’ (Helle).

Concerns occurred if the child had unfamiliar symptoms or a longer illness duration. In such situations, the parents described how they sometimes acted on emotions rather than common sense. Although the parents expressed confidence in their own abilities and intuition, they did not always think they were experts when their children were ill. Therefore, the parents sometimes used the OOH service for reassurance and to share the responsibility with a health care professional. ‘When I don’t think, it’s been nice to be alone with the responsibility. I have talked to the OOH service’ (Emilie).

Parental development

The parents we interviewed were more worried and insecure about their first child. The older their children became, and when they got a second child, the more experience they got in taking care of sick children themselves, and the OOH service was used less frequently; ‘I had probably called (the doctor) earlier with number one, because you don’t know anything!’ (Helle). Hence, as they developed as parents, they increasingly handled more severe situations themselves before they contacted the OOH health services.

Discussion and conclusion

Principal findings

The parents often used the OOH primary care instead of their own GP. This was due to insecurity about the severity of a symptom or disease, or inconvenient opening hours. The parents often sought information from the internet or from health care professionals. The first child seemed to cause much more concerns than a second child due to the parents being un-experienced with childhood diseases.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study provides new knowledge about the help seeking behaviour among parents to small children when using OOH care. In an explorative manner, this study contributes to the understanding of parents' reasons for using the OOH care and their managing of sick children.

The phenomenological approach contributed to an establishment of a broader understanding of the parents’ use of the OOH service through subjective experienced descriptions. It thus served as a guiding principle for the research process and more as a perspective rather than a direct research method. We intended to be as open as possible to the parents’ different descriptions. By doing this we have sought to disregard previous experiences and theories related to the use of the OOH care, although we had some knowledge and preconceived ideas on parents' use of the OOH care. This means that we did not directly analyse our interviews according to Husserl’s specific concepts; Intentionality, World of life, Reduction and Essence [17], but instead we more broadly studied and synthesised how the phenomenon ‘use of OOH care’ is experienced by the parents. It has been a strength to use the phenomenological perspective to gain in-depth descriptions of the parents’ experience with the OOH primary care service. Furthermore, it has helped to find the essence of the phenomenon by clarifying what recur or is kept constant across the parents’ experiences.

We aimed to recruit at least eight parents to gain variety in the responses as well as to have an opportunity to achieve a saturation point. We managed to recruit nine parents. The numbers of interviews were considered realistic to be able to perform and analyse within the given time frame for the study [22]. The informants were selected randomly by choosing the parents who were available in study period. A random selection is in line with the exploratory approach, since there is currently no evidence on which parents could be particularly interesting to recruit [23].

We did not observe any distinct differences in the findings between the parents, which could be the result of our rather homogenous group of well-educated mothers. Furthermore, they considered themselves as having an active role, when they are in contact with the health service. Thereby the informants seemed to represent a resourceful and high socioeconomic group. All in all, this can be considered as a limitation for the generalizability of the study. However, even though the group of parents seemed very alike, it was still possible to enable a nuanced understanding of the parents’ use of the medical service.

Findings in relation to other studies

In general, the parents found it easy to navigate the Danish health care system; however, it seemed that they used the OOH system for health problems that were not medically relevant for OOH care. The parents sometimes found it difficult to assess whether their children’s disease is ‘acute enough’ to contact the OOH care and sought information on the internet. They often found it challenging to find the right information that helps to deal with the disease but does not cause unnecessary concern. These findings are supported by another study, which pointed out that the parents needed to be sure that the sources of information they used were credible [24]. Previous studies at the ED also show that parents often lack clinical experience to accurately assess the severity of a disease or symptoms [5], and to determine when and where to seek medical advice [25]. There may be different perceptions of the term ‘acute’ between patients and health professionals [3,4]. However, also for health care professionals it can be difficult to assess the urgency of a health problem; under- and overassessment are common in telephone triage [26], and referrals to the hospital are in hindsight not always needed [27,28]. Thus, it is understandable that parents sometimes contact OOH services for medically non-urgent problems.

In accordance with the study of Williams, O’Rourke & Keogh, we found that concern, consideration of the children’s symptoms to be serious, and the need for advice and reassurance were the most important motives for contacting out-of-hours services [29]. In addition, studies have found that parents contact the doctor when they need to seek assurance and share responsibility [24], or because of what they perceived as lack of control over the condition or fear of serious illness [30]. This is compatible with our findings.

The parents seemed to be more concerned at the beginning of parenthood, when they had less experience with diseases, which was reduced when having child number two. Consequently, parents with two children needed less frequent urgent medical attention when their child was ill compared to parents with less experience. These findings are supported by several studies [24,25,31].

Apart from other reasons, health literacy skills may be related to parents’ frequent use of the OOH service. Health literacy is a multidimensional concept [32] and gathers several concepts that relate to what individuals need to make effective decisions about health for themselves or their families. Being able to assess the severity of a condition can be seen as a necessity for navigating appropriately in the health care system. The necessary skills required by modern health care are comprehensive [33]. Limited health literacy has been shown to be associated with increased use of emergency services [34–36]. A study has investigated the relationship between parents’ health literacy level and their likelihood of contacting the emergency services with a fever-affected child. Two thirds of the children who were not acute ill, had parents with a low level of health literacy [28]. This may indicate that parents who have a lower level of navigation are more likely to use the emergency services inadequately. Another study shows that parents with a low level of health literacy were more challenged when dealing with acute illness. This led to that the parents more frequently sought urgent medical care [37]. However, low health literacy may hypothetically also lead to lack of health services use, if people for example do not know who to contact in the health care system or suspect disease at all.

Hereby, it seems that health literacy can affect parents' contact with the acute health care system. At the same time, our study shows that parents’ contacts with the OOH care can affect their health literacy level as parents get more knowledge and experience in navigating the health care system. This means a continuous parental development and development in the parents’ health literacy. Thus, health literacy can be seen as a dynamic concept that is an integral part of parental development.

The parents in our study seemed to have high health literacy and did not find it difficult to navigate the health care system. On the contrary, they used the OOH care and the health care system in general strategically to suit their needs. The parents expressed that they used the health care as it makes sense in their world of life, partly because the opening hours of their own GP did not fit into their lives. Furthermore, as they gained experience in dealing with sick children and developed in parenting they tended to use the OOH care less. This is not necessarily due to the fact that their health literacy level is increased with greater knowledge of the disease and understanding of the intended use of health care system, but rather because their experiences have changed as they get more children.

Implications for practice

Overall, this study provides new knowledge on parents' use of OOH service and contributes with valuable knowledge according to an understanding of parents’ help seeking behaviour.

We suggest that there is a potential for supporting and influencing especially first-time parents in their use of the health service. A possible redirection of medically not urgent inquiries from OOH service to GP in daytime may advantageously be investigated by targeted efforts, of which both effects and health-economic implications should be studied.

Our study showed that the parents sometimes require support that is not offered by the system, but which they manage to get ‘despite’ the system, when calling the OOH care in what seems to be unnecessary from a medical point of view.

We suggest that future interventions not only emphasis on increasing the parents’ health literacy level to support them in their use of health care, but also focus on the importance of accessibility to health care. Therefore, changes at the structural and organisational level can help parents navigate in the health care system. One option could be to expand the regional nursing hotlines to all parents and not just those associated with the health consultant in the children’s first year of life, so all parents can get in touch with a health care professional for practical questions, in case of worry and insecurity about whether or not it is necessary to contact OOH services. However, it is important to use professionals who are highly skilled in telephone triage to make sure that parents on the one hand receive safe advice for self-care and on the other hand are not referred to OOH services for medically unnecessary health problems. As there also is a risk of only adding extra contacts with health care rather than redirecting patient flows, it is important to study the effects of such an intervention. This present study is based on a homogeneous group of parents. Therefore, a relevant next step would be to investigate how parents belonging to other socioeconomic groups, men or non-ethnic Danes use OOH care, and whether it is consistent with the findings of this study. The study highlights how the parents to a large extent understand how to navigate the system. On the other hand, it also shows that the system does not always fit the parents' needs. These are valuable insights that should not be disregarded in future optimizing of the health care system, but should be supplemented with knowledge about the behaviour of other socioeconomic and ethnic groups.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- OOH

Out-of-hours

- GP

General Practitioner

- ED

Emergency Department

- EMS

emergency medical service 112

Ethics

This study was performed as a part of ML's and CRT's Master of Science in Public Health Programme, and therefore has not been reported to the Data Inspectorate. However, person-identifying information was treated confidentially and unavailable to unauthorized persons. In addition, we obtained both written and oral consent from the informants.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1. Huibers L, et al. Consumption In Out-Of-Hours Health Care: Danes Double Dutch? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014; 32:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ertmann RK, et al. Infants’ Symptoms Of Illness Assessed By Parents: Impact And Implications. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2011; 29:67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morgans A, Burgess SJ.. What is a health emergency? The difference in definition and understanding between patients and health professionals. Aust Health Rev. 2011;35:284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Philips H, Remmen R, Paepe PD.. Out of hours care: a profile analysis of patients attending the emergency department and the general practitioner on call. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanders J. A review of health professional attitudes and patient perceptions on `inappropriate’ accident and emergency attendances. The implications for current minor injury service provision in England and Wales. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31:1097–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giesen P, Hammink A, Mulders A, et al. Te snel naar de huisartsenpost (Too easy to go to the GP cooperative). Medisch Contact. 2009; 06:239–242. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moth G, Flarup L, Christensen M, et al. Kontakt- og sygdomsmønsteret i laegevagten LV-KOS 2011 (Contact and disease pattern in the out-of-hours service LV-KOS 2011). Aarhus: Forskningsenheden for Almen Praksis, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Houston A, Pickering A. ’Do I don’t I call the doctor’: a qualitative study of parental perceptions of calling the GP out-of-hours . Health Expect. 2000;3:234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walsh A, Edwards H.. Management of childhood fever by parents: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54:217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zomorrodi A, Attia M.. Fever: Parental Concerns. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2008;9:238–243. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Enarson M, Ali S, Vandermeer B, et al. Beliefs and Expectations of Canadian Parents Who Bring Febrile Children for Medical Care. Pediatrics. 2012;130:905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clarke P. Evidence-based management of childhood fever: what pediatric nurses need to know. J Pediatr Nurs. 2014;29:372–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De S, Tong A, Isaacs D, et al. Parental perspectives on evaluation and management of fever in young infants: an interview study. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:717–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Danske Regioner, Kommunernes Landsforening, Økonomi- og Indenrigsministeriet, Finansministeriet, and Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse, (2013). Synlige resultater i sundhedsvaesenet – baggrundsrapport (Visible health care results – background report). [online] København: Sundheds- og AEldreministeriet. Available at: http://www.sum.dk/Aktuelt/Nyheder/Tal_og_analyser/2013/Maj/∼/media/Filer%20-%20dokumenter/Afrapportering-fra-Udvalget-for-bedre-incitamenter/Baggrundsrapport%20Synlige%20resultater%20i%20sundhedsvsenet.ashx.

- 15. Flarup L, Moth G, Christensen M, et al. danske laegevagt i internationalt perspektiv ‐ en sammenlignende undersøgelse af laegevagter i Danmark, England, Holland, Norge og Sverige (The Danish out-of-hours service in an international perspective - a comparative study of out-of-hours services in Denmark, England, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden). Aarhus: Forskningsenheden for Almen Praksis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kvale S. Doing interviews. 1st ed London: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Husserl E. Logical investigations. London: Routledge; (1973/1900). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elo S, Kynga¨s H.. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 62:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emerson R, Fretz R, Shaw L.. Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. 1st ed Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malterud K. Kapitel 17. Validitet (Chapter 17. Validity) In: Malterud K., ed., Kvalitative i Metoder Medisinsk Forskning En Innføring, 3rd ed Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cavanagh S. Content analysis: concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Res. 1997;4:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tanggaard L, Brinkmann S.. Kapitel 1. Interviewet: Samtalen som forskningsmetode (Chapter 1. The interview – the conversation as a research method). In: Brinkmann S. and Tanggaard L., ed., Kvalitative metoder, 2nd ed København: Hans Reitzels Forlag; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malterud K. Kapitel 3. Forskerens rolle gjennom forskningsprocessen (Chapter 3. The researchers role through the research process). In: Malterud K., ed., Kvalitative Metoder Medisinsk Forskning En Innføring, 3rd ed Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sahm L, Kelly M, McCarthy S, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of parents regarding fever in children: a Danish interview study. Acta Paediatr. 2015;105:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Winskill R, Keatinge D, Hancock S.. Influences on parents’ decisions when determining whether their child is sick and what they do about it: a pilot study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17:126–132. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huibers L, Smits M, Renaud V, et al. Safety of telephone triage in out-of-hours care: a systematic review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2011;29:198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ng JY, Fatovich DM, Turner VF, et al. Appropriateness of healthdirect referrals to the emergency department compared with self-referrals and GP referrals. Med J Aust. 2012;197:498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cook R, Thakore S, Morrison W, et al. To ED or not to ED: NHS 24 referrals to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2010;27:213–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams A, O’Rourke P, Keogh S.. Making choices: why parents present to the emergency department for non-urgent care. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kallestrup P, Bro F.. Parents’ beliefs and expectations when presenting with a febrile child at an out-of-hours general practice clinic. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;53:43–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morrison A, Chanmugathas R, Schapira M, et al. Caregiver Low Health Literacy and Nonurgent Use of the Pediatric Emergency Department for Febrile Illness. Acad Pediatr. 2014; 14:505–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health. Promot Int. 2000;15:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bo A, Friis K, Osborne R, et al. National indicators of health literacy: ability to understand health information and to engage actively with healthcare providers – a population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2011;199:1–941. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herndon J, Chaney M, Carden D.. Health literacy and emergency department outcomes: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2011; 57:334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Watson R. Europeans with poor ‘health literacy’ are heavy users of health services. BMJ. 2011;343:7741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morrison A, Schapira M, Gorelick M, et al. Low caregiver health literacy is associated with higher pediatric emergency department use and nonurgent visits. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:309–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]