Abstract

Time-dependent target occupancy is a function of both the thermodynamics and kinetics of drug-target interactions. However, while the optimization of thermodynamic affinity through approaches such as structure-based drug design is now relatively straight forward, less is understood about the molecular interactions that control the kinetics of drug complex formation and breakdown since this depends on both the ground and transition state energies on the binding reaction coordinate. In this opinion we highlight several recent examples that shed light on current approaches that are elucidating the factors that control the life-time of the drug-target complex.

Introduction

Drug discovery is a complex and expensive process with a high risk of failure. An analysis of 7,372 independent clinical trials from 2003 to 2011 revealed that only about 10% of the drug candidates were eventually approved by the FDA [1]. Two major contributors to the high attrition rate were lack of efficacy and unacceptable safety, both of which often result from unpredicted mechanisms of action (MOA) such as poor engagement with the primary target(s) and/or undesired binding to off-target proteins [2,3]. Since hit identification and lead optimization are early but critical steps that generate and select quality candidates for clinical development, new approaches at this stage of discovery, including activity-based profiling and parallel structure activity and liability relationship (SAR/SLR) screening, are now being used to better understand MOA [4,5]. Whilst these techniques will likely improve the success rate of new drug approvals, there is still a heavy reliance on drug-target binding affinities determined under conditions where drug and target are at equilibrium [6], and which therefore cannot fully cannot for drug-target engagement in the non-equilibrium environment of the human body. Thus, there is now increasing emphasis on strategies that include both the thermodynamics and kinetics of drug-target interactions so that the generation and selection of clinical candidates can be better informed and the rate of attrition further reduced [7–12].

Residence time (tR), the reciprocal of the rate at which the drug dissociates from the target to generate free (active) target (1/koff), is a non-equilibrium intrinsic parameter that quantitatively measures the lifetime of the drug-target complex [8]. In general, increasing drug-target residence time will be a valuable strategy for increasing the therapeutic window when the desired pharmacological outcome results from prolonged target occupancy, and provided that the drug dissociates rapidly from off-target proteins. The utility of residence time for the discovery and development of new drugs depends on several factors including drug pharmacokinetics, which can impact the benefits of kinetic selectivity, as well as target vulnerability and target turnover [11]. In this opinion we highlight some of the molecular factors that are known to influence residence time, in order to serve as guidance for the ultimate goal of rationally controlling the lifetime of the drug-target complex.

Kinetic mechanisms for prolonged residence time

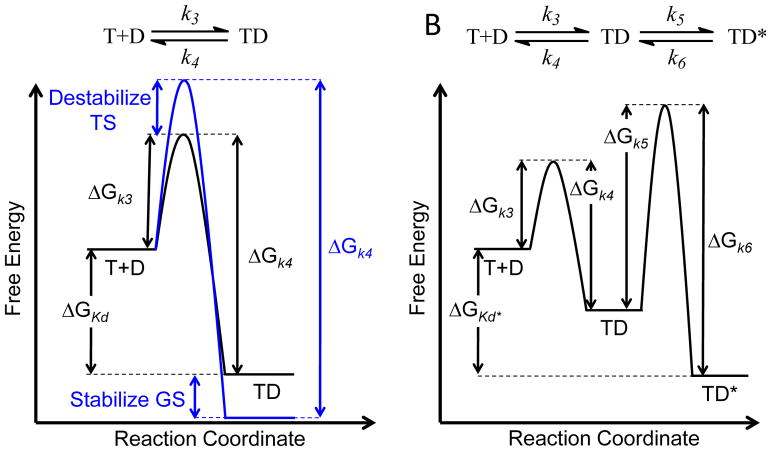

Several kinetic schemes can give rise to prolonged target occupancy including a simple one-step binding mechanism as well as a two-step induced-fit binding mechanism where the rapid formation of the initial drug-target complex (TD) is followed by a slow step leading to the final complex (TD*) [13] (Figure 1). Importantly, the on and off rates for formation and breakdown of the drug-target complex are controlled by the difference in free energy between the relevant ground and transition states on the binding reaction coordinate.

Figure 1. Reaction Coordinate for Drug-Target Complex Formation.

A. One-step binding mechanism showing that an increase in residence time (1/k4) can occur either by stabilization of the ground state (GS) and/or destabilization of the transition state (TS). The on-rate for drug-target complex formation (kon = k3) is second order and thus will depend on drug concentration. B. Two-step induced-fit binding mechanism in which the rapid formation of the initial drug-target complex (TD) is followed by a slow step leading to the final complex (TD*). The forward rate for formation of TD* is k5 and is thus first order.

Consideration of the precepts behind the reaction coordinate diagram lead to several key points including, (i) that stabilization of the drug-target complex ground state may or may not affect the off-rate depending on whether the stability of the transition state is also altered, (ii) that a compound can bind to two targets with the same thermodynamic affinity but with different on and off-rates, thereby displaying kinetic but not thermodynamic selectivity, (iii) that a drug with a slow on rate will always have a slow-off rate, and (iv) that a drug with a slow-off rate may or may not bind rapidly to the target. The first point is particularly important given the almost exclusive focus in drug discovery campaigns on increasing the stability of the drug-target complex.

Since technological advances have now reached a point where robust kinetic data can be generated in high-throughput mode, one might wonder why structure-kinetic relationships (SKRs) have not become part of the paradigm in early drug discovery to actively hunt for small molecules with long residence times. The biggest hurdle is the lack of specific information to guide medicinal chemistry campaigns explicitly aimed at rationally modifying residence time. Structural tools, such as X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, can readily capture ground state structures and thus be used to elucidate molecular interactions that are important for optimizing binding affinity. However, transition states are short-lived and, with the exception of approaches pioneered by Schramm and coworkers [14], there is generally very limited structural information available to rationalize how to alter their stability. Efforts to unravel the molecular basis for residence time include the analysis of molecular properties of drugs that correlate with residence time, and the investigation of the conformational changes in the target linked to residence time using X-ray structural data, and thus focused on drug-target ground states, in some cases supplemented with computational approaches to provide insight into the structure of both ground and transition states on the binding reaction coordinate. Table 1 summarizes data for a number of targets in order to provide insight into diversity of approaches and mechanisms that have been uncovered, and in the subsequent discussion we highlight a few target classes to exemplify the current state of knowledge.

Table 1.

Mechanisms that modulate the life-time of the drug-target complex

| Target | Mechanism | Compound |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus FabI | Ordering of the substrate binding loop (SBL). | Alkyl diphenyl ether PT119, tR 12.5 hr, 20 °C [15]. |

| M. tuberculosis FabI | Steric clash in the TS between SBL helix-6 and 7 [16]. | Triazole diphenyl ether PT504, tR 10 hr, 25 °C [17]. |

| Thermolysin | Interaction with Asn112 prevents conformational change required for ligand release [18]. | Phosphonopeptide 18, tR 168 days. |

| Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | Gating mechanism involving rotation of Val260 [19]. | DADMe–immucillin-H, tR 12 min 37°C [20]. |

| Hsp90 | Entropically driven binding affects on and off rates [21]. | Phenyl-triazole-benzamide 20 tR 51 min. |

| IDH2/R140Q | Loop motion associated with an allosteric binding site [22]. | AGI-6780, tR 120 min. |

| DOT1L | Occupancy of binding pocket adjacent to SAM binding site [23]. | EPZ004777, tR 55 min, 25°C. |

| Soluble epoxide hydrolase | Interactions with Tyr153 and Met189 control TS stability. [24]. | TPPU tR 11 min. |

| Heat shock protein 90 | Ligand desolvation: polar substituents decrease kon [25]. | Indazole 3c, tR 57 min, 25°C. |

|

| ||

| CDK2/9 | Type I. Conformational change in DFG loop. | Roniciclib, tR 400 min [26]. |

| CDK8/CycC | Type II. H-bonds with hinge and hydrophobic contacts with front pocket. | Pyrazole 2, tR 32 hr [27]. |

| p38aMAP kinase | Type 1.5. Disruption of the R-spine. | Dibenzosuberone 6g, tR 32 hr [28]. |

| RIP1 kinase | Type II/III. Increase in cLogP reduced koff. | Benzoxazepine 22, tR 5 hr [29]. |

| Btk | Reversible covalent. Steric hindrance of α-proton abstraction [30]. | Pyrazolopyrimidine 9, tR 167 hr. |

| Btk | Irreversible. Reduced electrophilicity increases selectivity. | Acalabrutinib [31]. |

|

| ||

| CCR5 | Allosteric ligand with alternative receptor conformation. | 873140, tR > 136 hr, RT [32]. |

| Muscarinic M3 receptor | Coulomb repulsion between ligand and Lys523 [33]. | Tiotropium, tR 39 hr. |

| β2 adrenergic receptor | Ligand desolvation [34]. | Alprenolol, tR 4 min, 37°C. |

| Adenosine A2A receptor | ETH triad forms a lid preventing ligand dissociation [35]. | ZM241358, tR 84 min. |

1. Bacterial Enoyl-ACP Reductase – Reorganization of the Substrate Binding Loop

The bacterial enoyl-ACP reductase FabI is a target for the development of new antibacterial agents. Previous studies on the Francisella tularensis FabI (ftFabI) demonstrated that residence time of diphenyl ether-based transition state analogs directly correlated with in vivo efficacy and was a better indicator of preclinical antibacterial activity than thermodynamic affinity [36]. Subsequently, structure-guided inhibitor discovery led to the synthesis of diphenyl ethers that are slow tight binding inhibitors of the FabI from Staphylococcus aureus (saFabI) with residence times ranging from 2 to 750 min [15]. SKR studies revealed that hydrophobic substituents at the 5-position of A ring and a small and moderately polar group at the 2′-postion of B ring increase the residence time. Time-dependent inhibition of FabI is coupled to motions of a substrate binding loop (SBL) that lies close to the active site and which generally adopts an α-helical conformation that covers the substrate/ligand binding site in the enzyme-inhibitor complex. Interestingly, a very strong correlation between the binding affinity and residence time was observed, suggesting that the increase of residence time is almost solely from the stabilization of the final ground state. This observation is different from the free energy analysis of ftFabI where a combination of ground state stabilization and transition state destabilization contributed to longer residence for the diphenyl ether inhibitors [10]. These findings highlight that even for targets with high structural similarity, the molecular factors that modulate residence time can differ significantly even for inhibitors that share the same core and overall kinetic binding mechanism.

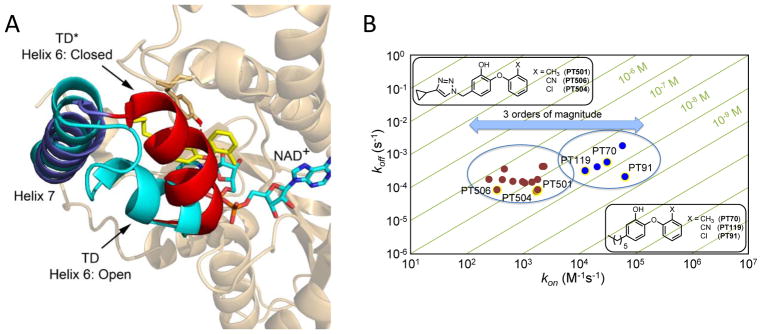

The structural studies were extended to the FabI enzyme from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (mtFabI, InhA) where X-ray crystallography and molecular dynamic (MD) simulations revealed that two-step induced-fit inhibition involved the movement of helix-6, which comprises part of the SBL in this enzyme, from an open conformation to a closed conformation [16]. Multidimensional free energy landscapes were used to build a model of the transition state for the slow step which was interrogated by site-directed mutagenesis and the synthesis of a triazole-based inhibitor designed to selectively destabilize the transition state [37]. Further analysis of a focused library of diphenyl ethers revealed that the triazole substituent reduced kon as well as koff, indicating a specific effect on the transition state, and that larger, more hydrophobic substituents resulted in a further reduction of kon and increase in tRuntil a “steric limit” was reached [17].

2. Kinases

Reversible (non-covalent) inhibitors

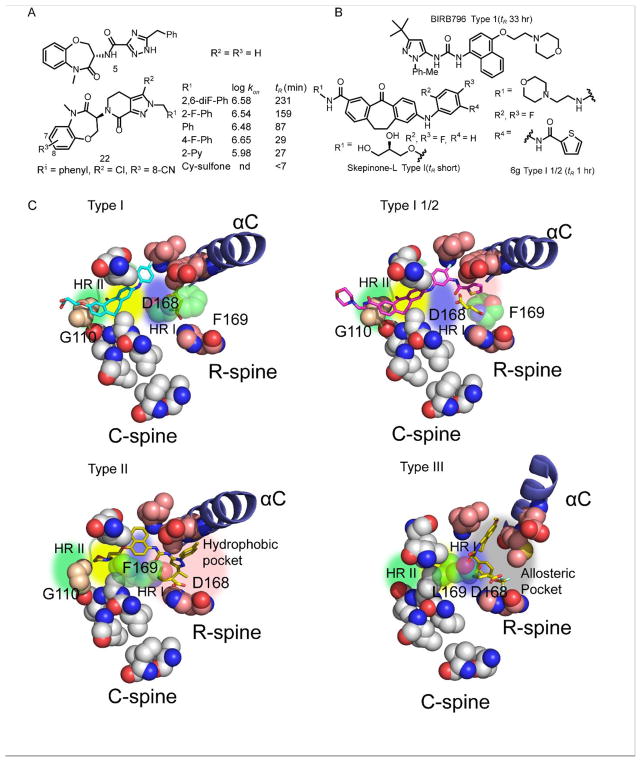

Kinases represent a major focus of drug discovery efforts [38], and a rich source of SKR is available for exploring the mechanism of time-dependent inhibition in this enzyme family. Kinase inhibitor classification generally focuses on the conformation of the DFG motif at the N-terminus of the activation loop: Type I inhibitors bind to the ATP binding pocket in which the DFG motif occupies a position similar to that adopted in the active enzyme (the DFG-In conformation), while Type II inhibitors bind to an extended region in the ATP binding pocket usually with an inactive conformation of the enzyme in which the DGF motif has flipped away from the active site (the DFG-Out conformation). This classification has been supplemented with additional binding modes in which inhibitors bind to a site adjacent to the bound ATP substrate (Type III) or to an allosteric site remote from the ATP binding pocket (Type IV) [39–41].

SKR studies have revealed that Type II/III inhibitors generally have longer residence times than Type I inhibitors, and there have been numerous attempts to develop Type II/III kinase inhibitors either with the aim of generating slow-off compounds and/or because of the presumption that Type II/III inhibitors are more selective than Type I inhibitors. A retrospective analysis of the Pfizer database, in which 392 out of 430 slow-off compounds were kinase inhibitors, revealed that compounds with clogP >5, as well as molecular weight >500 and number of rotatable bond >5, were more likely to have a long residence time [42]. The correlation between hydrophobicity and residence time is present in other systems, such as CDK8/CycC where an HTS identified pyrazole-urea-based inhibitors with residence times of up to 32 hr (Table 1) [27]. An exploration of SKR demonstrated that while hydrogen bonding interactions with hinge residues were important for slow dissociation, the very long residence times were achieved through hydrophobic groups binding in the front pocket. This analysis also revealed that although the “DFG” motif (DMG in CDK8) was in the out-conformation, the position of this motif was not thought to correlate with residence time.

Receptor interacting protein 1 (RIP1) kinase: Type III inhibitors

Receptor interacting protein 1 (RIP1) kinase is a target for treating inflammatory diseases. Screening of GlaxoSmithKline’s DNA-encoded libraries followed by optimization led to the discovery of benzoxazepinone 5 (GSK2982772) which has a residence time of 162 min on RIP1 kinase (Figure 3) [43]. Structural studies revealed that 5 occupies the allosteric pocket characteristic of Type III inhibitors but also a portion of the ATP binding site. More recently, Takeda reported the discovery of a brain penetrant RIP1 kinase inhibitor (22) which has a similar binding mode to 5, occupying the allosteric binding pocket and also overlapping with the ATP binding site [29]. Compound 22 has a residence time of 300 min on RIP1 kinase, and binding kinetics were measured for a series of analogs in order to generate SKR for enzyme inhibition (Figure 3). While modifications to R3, which is solvent accessible, had no effect on binding kinetics, changes to the R1 phenyl group, which binds in the allosteric pocket, had the largest impact. In particular, R1 substituents that increased clogP generally resulted in an increase in kon and a decrease in koff. In addition, it was found that kon and koff values were not strongly coupled, suggesting that the rates of formation and breakdown of the drug-target complex could be optimized independently.

Figure 3. Kinase inhibitors and interactions that govern residence time.

A. SKR for RIP1 kinase inhibition. B. p38α MAP kinase inhibitors including SKR for analogs of skepinone. C. Structures of Type I, I½ and II inhibitor complexes with p38α MAP kinase and the Type III inhibitor complex with RIP1 kinase highlighting motifs such as the DFG loop as well two hydrophobic spines, the regulatory spine (R-spine) and the catalytic spine (C-spine) [44]. The Type I inhibitor Skepinone-L binds in the ATP pocket near hinge region II (HRII) (PDB 3QUE) [45]. The Type I½ inhibitor 6g is also competitive with ATP but gains residence time by reaching HRI and a hydrophobic pocket formed by disruption of the R-spine (PDB 5TBE) [46]. The Type II inhibitor BIRB796 (PDB 1KV2) reaches much deeper into this hydrophobic pocket [47]. The Type III necrostatin analog accesses an allosteric pocket adjacent to the ATP site in RIP 1 kinase (PDB 4ITI) [48].

p38a MAP kinase: Type 1½ inhibitors

A second recent system where there has been a specific focus on developing slow-off compounds is p38α MAP kinase which is a target for treating autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Long residence time Type II inhibitors of p38α MAP kinase have been developed, but BIRB796 (tR 33 hr) lacks selectivity. Laufer and colleagues introduced modifications into the short residence time Type I inhibitor Skepinone-L to disrupt the hydrophobic backbone regulatory spine (R-spine), leading to Type 1½ inhibitors such as 6g with an improved residence time of 1 hr [28] (Figure 3).

Covalent inhibitors

Covalent inhibitors usually have an electrophilic group that reacts with electron rich amino acid such Cys, Ser or Thr forming an irreversible enzyme-inhibitor complex with infinitely long residence time [49]. Although concerns about off-target activity have limited the use of covalent inhibitors as drugs [50], active progress has been made by incorporating moderately reactive groups into compounds with intrinsically high specific affinity for the target and by accurately positioning the reactive group close to the nucleophilic residue [51,52]. Well-known irreversible inhibitors of kinases include afatinib and ibrutinib, which react with a conserved Cys in the active sites of EGFR and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk), respectively. More recently, the butynone-based Btk inhibitor acalabrutinib has been reported, which is thought to have improved selectivity over ibrutinib due to reduced electrophilicity of the warhead [31]. A second strategy to improve selectivity of covalent kinase inhibitors has involved the introduction of the electron-withdrawing nitrile group at the Cα carbon of the acrylamide electrophile so that Michael addition is now reversible [30]. While the equilibrium for thiol addition in solution lies in favor of the intact electrophile, it was found that the introduction of bulky groups into the inhibitor decreased the acidity of the α-proton, thus reducing the rate of thiol elimination and stabilizing the covalent enzyme-inhibitor complex. This strategy was used to develop inhibitors that had residence times of up to 167 hr on Btk (Table 1).

3. GPCRs

Like kinases, there are also several well-known examples of long residence time drug-target complexes in the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family such as the interaction of tiotropium with the muscarinic receptor family and the binding of antagonists to CCR5 (Table 1). In addition, empirical SKR studies have also attempted to dissect the molecular properties that control the interaction of ligands with GPCRs, such as the analysis of >1800 compounds that bind to the dopamine D2 receptor, which revealed that that smaller, more polar and less lipophilic compounds tend to have shorter residence times [53], again highlighting the role of hydrophobicity in slow off rates. While empirical SKR will likely be the main driver for med chem campaigns in the short term, the development of computational approaches that can accurately predict on and off rates will have a transformative impact on the application of binding kinetics to drug discovery. Thus, we close this opinion by briefly describing two systems where MD simulations have been used to investigate the mechanism of ligand binding to GPCRs.

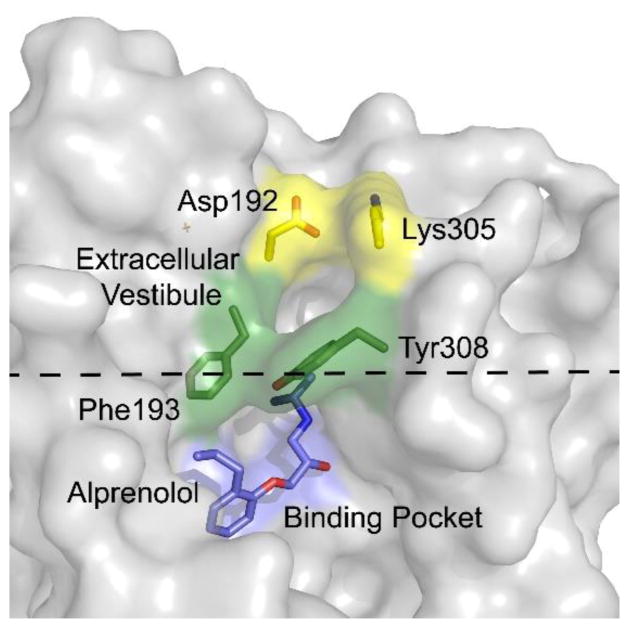

The β2-adrenergic receptor

The β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) is a GPCR drug target for treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. β2AR has been a focus of several MD studies aimed at modeling the mechanism of binding and unbinding of several antagonists. A study by Wang and Duan focused on the unbinding of carazolol from β2AR using random acceleration molecular dynamics (RAMD) [54]. A random force was applied to carazolol to break interactions in the binding pocket after which the antagonist was allowed to find the optimal pathway to exit the receptor, which was found to involve loss of a salt bridge near the extracellular surface of the receptor. More recently, Dror et al. described the binding of the β-blocker alprenolol to β2AR using an approach in which the inhibitor was blind to the location of the binding pocket and therefore minimizing bias towards a specific binding site or pose [34]. The MD studies showed that the rate limiting step for formation of the receptor-antagonist complex involved desolvation of the ligand upon entering the β2AR extracellular vestibule (Figure 4).

Figure 4. MD simulations of alprenolol binding to β2AR.

Binding of alprenolol to the extracellular vestibule disrupts a salt bridge between Asp192 and Lys305 and results in desolvation of the ligand. Subsequent entry of the ligand into the binding pocket involves disruption of a πstacking interaction between Phe193 and Tyr308 [34].

The adenosine A2A receptor

Very recently, Guo et al applied temperature accelerated MD (TAMD) to the dissociation of ZM241385 from the adenosine A2A receptor [35]. In this approach residues were identified that contacted the inhibitor upon exiting the binding site, which were then tested using site directed mutagenesis and a radioligand kinetics assay. A triad was identified involving Glu, Thr, and His residues that interact with ZM241385 transiently on exit from the binding cavity. When mutated to Gln, Ala, and Ala, respectively, the residence time is reduced to <5 min compared to a residence time of 84 min in the wild-type receptor [24]. This example, together with the studies on the binding of carazolol and alprenolol to β2AR described in the preceding section highlight some of the advances that are being made in the use of computational methods to understand the molecular factors that control drug-target binding kinetics.

Summary

Time-dependent target occupancy is controlled by both the kinetics and thermodynamics of drug-target interactions, as well as drug pharmacokinetics (PK) which controls drug concentration at the target site. Thus, drug selectivity contains both thermodynamic and kinetic components. In a limiting situation where a drug binds to two targets with the same affinity, kinetic selectivity can provide discrimination between on and off target proteins. For example, where continued target occupancy is required for the desired pharmacological outcome, a drug with a long residence time of the target can be dosed less frequently and/or at lower doses leading to an increase in the therapeutic window. Although attractive, the ability to take full advantage of kinetic selectivity requires knowledge to guide the design of compounds with altered binding kinetics. In this opinion we provide a few examples to highlight some of the approaches that are being used to rationally modulate residence time and to understand the molecular factors that control the lifetime of the drug-target complex. Protein conformational change is clearly a key factor in time-dependent drug binding, for instance in the two-step induced-fit mechanism [55], and there are numerous examples where structural data reveal significant ligand induced protein motions that correlate with the time dependent inhibition in targets including HIV integrase [56,57], methionine adenosyltransferase [58] and HCV NS3 protease [59,60]. However, in only a very few cases is explicit knowledge available on the structure of the transition state on the binding reaction coordinate, such as the example we give for mtFabI. In many other cases the understanding of drug-target kinetics relies on SKR either of the ligands alone or, as is the case for kinases, with detailed knowledge of changes in protein structure as well. While experimental SKR data will likely be the mainstay for developing ligands with altered kinetic profiles, it is very encouraging to see the upsurge in the use of computational methods for calculating on and off rates. Significant progress has been made for targets such as GPCRs and the authors look forward to additional enhancements in computational methods for understanding and predicting drug-target binding kinetics.

Figure 2. Time-Dependent Inhibition of mtFabI (InhA).

A. Two-step slow-onset inhibition of InhA involves the movement of helix-6 from an open position in TD to a closed position in TD*. B. 2-D kinetic map of koff vs kon, with diagonal lines showing Ki*, the dissociation constant of TD*, for a series of diphenyl ether mtFabI inhibitors. The triazole analogues have longer residence times than the alkyl-diphenyl ethers but bind either with similar potency or less tightly with kon values that are ~100–1000-fold smaller than the kon values for the corresponding alkyl diphenyl ethers: thus, the increase in residence time of the triazole-based inhibitors results from destabilization of the transition state on the reaction coordinate between TD to TD*.

Highlights.

Drug selectivity has both thermodynamic and kinetic components.

Kinases and GPCRs are a rich source of structure-kinetic relationships.

Both ground and transition state energies control binding kinetics.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health GM102864 and the PhRMA Foundation. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health GM102864 and the PhRMA Foundation. JNI was supported by the National Institutes of Health GM092714 and a Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need (GAANN) Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:40–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrowsmith J. Trial watch: Phase II failures: 2008–2010. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:328–329. doi: 10.1038/nrd3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrowsmith J. Trial watch: phase III and submission failures: 2007–2010. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:87. doi: 10.1038/nrd3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nomura DK, Dix MM, Cravatt BF. Activity-based protein profiling for biochemical pathway discovery in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:630–638. doi: 10.1038/nrc2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Cvijic ME, Lippy J, Myslik J, Brenner SL, Binnie A, Houston JG. Case study: technology initiative led to advanced lead optimization screening processes at Bristol-Myers Squibb, 2004–2009. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang R, Monsma F. Binding kinetics and mechanism of action: toward the discovery and development of better and best in class drugs. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2010;5:1023–1029. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2010.520700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7**.Swinney DC. Biochemical mechanisms of drug action: what does it take for success? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:801–808. doi: 10.1038/nrd1500. An early discussion of non-equilibrium binding mechanisms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8**.Copeland RA, Pompliano DL, Meek TD. Drug-target residence time and its implications for lead optimization. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:730–739. doi: 10.1038/nrd2082. A key review that defined drug-target residence time and highlighted the importance of residence time in prolonged drug activity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang R, Monsma F. The importance of drug-target residence time. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:488–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Lu H, Tonge PJ. Drug-target residence time: critical information for lead optimization. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.176. A review that highlights the connection between residence time and drug activity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11**.Tonge PJ. Drug-Target Kinetics in Drug Discovery. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2018;9:29–39. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00185. A review that discusses the importance of kinetic selectivity and target vulnerability. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuetz DA, de Witte WEA, Wong YC, Knasmueller B, Richter L, Kokh DB, Sadiq SK, Bosma R, Nederpelt I, Heitman LH, et al. Kinetics for Drug Discovery: an industry-driven effort to target drug residence time. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22:896–911. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison JF, Walsh CT. The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1988;61:201–301. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states, transition-state analogs, dynamics, thermodynamics, and lifetimes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:703–732. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100742. A combination of X-ray structural studies and MD simulations was used to determine the structure of the transition state on the inhibition reaction cooridnate. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang A, Schiebel J, Yu W, Bommineni GR, Pan P, Baxter MV, Khanna A, Sotriffer CA, Kisker C, Tonge PJ. Rational optimization of drug-target residence time: insights from inhibitor binding to the Staphylococcus aureus FabI enzyme-product complex. Biochemistry. 2013;52:4217–4228. doi: 10.1021/bi400413c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li HJ, Lai CT, Pan P, Yu W, Liu N, Bommineni GR, Garcia-Diaz M, Simmerling C, Tonge PJ. A structural and energetic model for the slow-onset inhibition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enoyl-ACP reductase InhA. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:986–993. doi: 10.1021/cb400896g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spagnuolo LA, Eltschkner S, Yu W, Daryaee F, Davoodi S, Knudson SE, Allen EK, Merino J, Pschibul A, Moree B, et al. Evaluating the Contribution of Transition-State Destabilization to Changes in the Residence Time of Triazole-Based InhA Inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:3417–3429. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cramer J, Krimmer SG, Fridh V, Wulsdorf T, Karlsson R, Heine A, Klebe G. Elucidating the Origin of Long Residence Time Binding for Inhibitors of the Metalloprotease Thermolysin. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:225–233. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decherchi S, Berteotti A, Bottegoni G, Rocchia W, Cavalli A. The ligand binding mechanism to purine nucleoside phosphorylase elucidated via molecular dynamics and machine learning. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6155. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Gebre ST, Cameron SA, Li L, Babu YS, Schramm VL. Intracellular rebinding of transition-state analogues provides extended in vivo inhibition lifetimes on human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:15907–15915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.801779. A cellular study where prolonged occupancy of purine nucleoside phosphorylase by a transition state analogue inhibitor is shown to be a combination of residence time and rebinding effects. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amaral M, Kokh DB, Bomke J, Wegener A, Buchstaller HP, Eggenweiler HM, Matias P, Sirrenberg C, Wade RC, Frech M. Protein conformational flexibility modulates kinetics and thermodynamics of drug binding. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2276. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02258-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang F, Travins J, DeLaBarre B, Penard-Lacronique V, Schalm S, Hansen E, Straley K, Kernytsky A, Liu W, Gliser C, et al. Targeted inhibition of mutant IDH2 in leukemia cells induces cellular differentiation. Science. 2013;340:622–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1234769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basavapathruni A, Jin L, Daigle SR, Majer CR, Therkelsen CA, Wigle TJ, Kuntz KW, Chesworth R, Pollock RM, Scott MP, et al. Conformational adaptation drives potent, selective and durable inhibition of the human protein methyltransferase DOT1L. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2012;80:971–980. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lotz SD, Dickson A. Unbiased Molecular Dynamics of 11 min Timescale Drug Unbinding Reveals Transition State Stabilizing Interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:618–628. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuetz DA, Richter L, Amaral M, Grandits M, Gradler U, Musil D, Buchstaller HP, Eggenweiler HM, Frech M, Ecker GF. Ligand Desolvation Steers On-Rate and Impacts Drug Residence Time of Heat Shock Protein 90 (Hsp90) Inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2018;61:4397–4411. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayaz P, Andres D, Kwiatkowski DA, Kolbe CC, Lienau P, Siemeister G, Lucking U, Stegmann CM. Conformational Adaption May Explain the Slow Dissociation Kinetics of Roniciclib (BAY 1000394), a Type I CDK Inhibitor with Kinetic Selectivity for CDK2 and CDK9. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:1710–1719. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider EV, Bottcher J, Huber R, Maskos K, Neumann L. Structure-kinetic relationship study of CDK8/CycC specific compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8081–8086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305378110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walter NM, Wentsch HK, Buhrmann M, Bauer SM, Doring E, Mayer-Wrangowski S, Sievers-Engler A, Willemsen-Seegers N, Zaman G, Buijsman R, et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Type I1/2 p38alpha MAP Kinase Inhibitors with Excellent Selectivity, High Potency, and Prolonged Target Residence Time by Interfering with the R-Spine. J Med Chem. 2017;60:8027–8054. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshikawa M, Saitoh M, Katoh T, Seki T, Bigi SV, Shimizu Y, Ishii T, Okai T, Kuno M, Hattori H, et al. Discovery of 7-Oxo-2,4,5,7-tetrahydro-6 H-pyrazolo[3,4- c]pyridine Derivatives as Potent, Orally Available, and Brain-Penetrating Receptor Interacting Protein 1 (RIP1) Kinase Inhibitors: Analysis of Structure-Kinetic Relationships. J Med Chem. 2018;61:2384–2409. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30**.Bradshaw JM, McFarland JM, Paavilainen VO, Bisconte A, Tam D, Phan VT, Romanov S, Finkle D, Shu J, Patel V, et al. Prolonged and tunable residence time using reversible covalent kinase inhibitors. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:525–531. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1817. An important advance in the development of long residence time inhibitors in which the lifetime of the enzyme-inhibitor complex is tuned by altering the stability of a reversible covalent adduct. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barf T, Covey T, Izumi R, van de Kar B, Gulrajani M, van Lith B, van Hoek M, de Zwart E, Mittag D, Demont D, et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196): A Covalent Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor with a Differentiated Selectivity and In Vivo Potency Profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;363:240–252. doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.242909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watson C, Jenkinson S, Kazmierski W, Kenakin T. The CCR5 receptor-based mechanism of action of 873140, a potent allosteric noncompetitive HIV entry inhibitor. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1268–1282. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.008565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33*.Tautermann CS, Kiechle T, Seeliger D, Diehl S, Wex E, Banholzer R, Gantner F, Pieper MP, Casarosa P. Molecular basis for the long duration of action and kinetic selectivity of tiotropium for the muscarinic M3 receptor. J Med Chem. 2013;56:8746–8756. doi: 10.1021/jm401219y. Site-directed mutagensis and MD simulations are used in concert to reveal the interactions that control the residence time of tiotropium on the M3 receptor. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dror RO, Pan AC, Arlow DH, Borhani DW, Maragakis P, Shan Y, Xu H, Shaw DE. Pathway and mechanism of drug binding to G-protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13118–13123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104614108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo D, Pan AC, Dror RO, Mocking T, Liu R, Heitman LH, Shaw DE, APIJ Molecular Basis of Ligand Dissociation from the Adenosine A2A Receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2016;89:485–491. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.102657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu H, England K, am Ende C, Truglio JJ, Luckner S, Reddy BG, Marlenee NL, Knudson SE, Knudson DL, Bowen RA, et al. Slow-onset inhibition of the FabI enoyl reductase from francisella tularensis: residence time and in vivo activity. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:221–231. doi: 10.1021/cb800306y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai CT, Li HJ, Yu W, Shah S, Bommineni GR, Perrone V, Garcia-Diaz M, Tonge PJ, Simmerling C. Rational Modulation of the Induced-Fit Conformational Change for Slow-Onset Inhibition in Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA. Biochemistry. 2015;54:4683–4691. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferguson FM, Gray NS. Kinase inhibitors: the road ahead. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:353–377. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Z, Wu H, Wang L, Liu Y, Knapp S, Liu Q, Gray NS. Exploration of type II binding mode: A privileged approach for kinase inhibitor focused drug discovery? ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1230–1241. doi: 10.1021/cb500129t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roskoski R., Jr Classification of small molecule protein kinase inhibitors based upon the structures of their drug-enzyme complexes. Pharmacol Res. 2016;103:26–48. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kooistra AJ, Kanev GK, van Linden OP, Leurs R, de Esch IJ, de Graaf C. KLIFS: a structural kinase-ligand interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D365–371. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller DC, Lunn G, Jones P, Sabnis Y, Davies NL, Driscoll P. Investigation of the effect of molecular properties on the binding kinetics of a ligand to its biological target. MedChemComm. 2012;3:449–449. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris PA, Berger SB, Jeong JU, Nagilla R, Bandyopadhyay D, Campobasso N, Capriotti CA, Cox JA, Dare L, Dong X, et al. Discovery of a First-in-Class Receptor Interacting Protein 1 (RIP1) Kinase Specific Clinical Candidate (GSK2982772) for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. J Med Chem. 2017;60:1247–1261. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim J, Ahuja LG, Chao FA, Xia Y, McClendon CL, Kornev AP, Taylor SS, Veglia G. A dynamic hydrophobic core orchestrates allostery in protein kinases. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1600663. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koeberle SC, Romir J, Fischer S, Koeberle A, Schattel V, Albrecht W, Grutter C, Werz O, Rauh D, Stehle T, et al. Skepinone-L is a selective p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;8:141–143. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wentsch HK, Walter NM, Buhrmann M, Mayer-Wrangowski S, Rauh D, Zaman GJR, Willemsen-Seegers N, Buijsman RC, Henning M, Dauch D, et al. Optimized Target Residence Time: Type I1/2 Inhibitors for p38alpha MAP Kinase with Improved Binding Kinetics through Direct Interaction with the R-Spine. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:5363–5367. doi: 10.1002/anie.201701185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pargellis C, Tong L, Churchill L, Cirillo PF, Gilmore T, Graham AG, Grob PM, Hickey ER, Moss N, Pav S, et al. Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase by utilizing a novel allosteric binding site. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:268–272. doi: 10.1038/nsb770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie T, Peng W, Liu Y, Yan C, Maki J, Degterev A, Yuan J, Shi Y. Structural basis of RIP1 inhibition by necrostatins. Structure. 2013;21:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powers JC, Asgian JL, Ekici OD, James KE. Irreversible inhibitors of serine, cysteine, and threonine proteases. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4639–4750. doi: 10.1021/cr010182v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalgutkar AS, Dalvie DK. Drug discovery for a new generation of covalent drugs. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2012;7:561–581. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.688744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh J, Petter RC, Baillie TA, Whitty A. The resurgence of covalent drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nrd3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mah R, Thomas JR, Shafer CM. Drug discovery considerations in the development of covalent inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tresadern G, Bartolome JM, Macdonald GJ, Langlois X. Molecular properties affecting fast dissociation from the D2 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:2231–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang T, Duan Y. Ligand entry and exit pathways in the beta2-adrenergic receptor. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:1102–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tummino PJ, Copeland RA. Residence Time of Receptor– Ligand Complexes and Its Effect on Biological Function. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8465. doi: 10.1021/bi8002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langley DR, Samanta HK, Lin Z, Walker Ma, Krystal MR, Dicker IB. The terminal (catalytic) adenosine of the HIV LTR controls the kinetics of binding and dissociation of HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13481–13488. doi: 10.1021/bi801372d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garvey EP, Schwartz B, Gartland MJ, Lang S, Halsey W, Sathe G, Carter HL, Weaver KL. Potent inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase display a two-step, slow-binding inhibition mechanism which is absent in a drug-resistant T66I/M154I mutant. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1644–1653. doi: 10.1021/bi802141y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez B, Pajares MA, Hermoso JA, Alvarez L, Garrido F, Sufrin JR, Sanz-Aparicio J. The crystal structure of tetrameric methionine adenosyltransferase from rat liver reveals the methionine-binding site. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:363–375. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Y, Stoll VS, Richardson PL, Saldivar A, Klaus JL, Molla A, Kohlbrenner W, Kati WM. Hepatitis C NS3 protease inhibition by peptidyl-alpha-ketoamide inhibitors: kinetic mechanism and structure. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;421:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garvey EP. Structural Mechanisms of Slow-Onset, Two-Step Enzyme Inhibition. Curr Chem Biol. 2010;4:64–73. [Google Scholar]