Abstract

Objective: Our objective was to describe the development and evaluation of a course programme in existential communication targeting general practitioners (GPs).

Design: The UK Medical Research Council’s (MRC) framework for complex intervention research was used as a guide for course development and evaluation and was furthermore used to structure this paper. The development phase included: identification of existing evidence, description of the theoretical framework of the course, designing the intervention and deciding for types of evaluation. In the evaluation phase we measured self-efficacy before and after course participation. To explore further processes of change we conducted individual, semi-structured telephone interviews with participants.

Subjects and setting: Twenty practising GPs and residentials in training to become GPs from one Danish region (mean age 49).

Results: The development phase resulted in a one-day vocational training/continuing medical education (VT/CME) course including the main elements of knowledge building, self-reflection and communication training. Twenty GPs participated in the testing of the course, nineteen GPs answered questionnaires measuring self-efficacy, and fifteen GPs were interviewed. The mean scores of self-efficacy increased significantly. The qualitative results pointed to positive post course changes such as an increase in the participants’ existential self-awareness, an increase in awareness of patients in need of existential communication, and an increase in the participants’ confidence in the ability to carry out existential communication.

Conclusions: A one-day VT/CME course targeting GPs and including the main elements of knowledge building, self-reflection and communication training showed to make participants more confident about their ability to communicate with patients about existential issues and concerns.

Key points

Patients with cancer often desire to discuss existential concerns as part of clinical care but general practitioners (GPs) lack confidence when discussing existential issues in daily practice.

In order to lessen barriers and enhance existential communication in general practice, we developed a one-day course programme.

Attending the course resulted in an increase in the participants’ confidence in the ability to carry out existential communication.

This study adds knowledge to how confidence in existential communication can be increased among GPs.

Keywords: Communication, cancer, existential, spiritual, religious, general practitioners, vocational training, continuing medical education

Introduction

Comprehensive evidence demonstrates that cancer patients frequently experience multiple existential problems and concerns that impact negatively on their physical and mental health [1]. In the medical literature, some of the most common existential questions and concerns relate to the need to find meaning and purpose (“why me?”), fear of an insecure future and death, loss of relationships, feelings of regret, guilt and anger, faith in God or some higher power [2].

Studies show that cancer patients in palliative care often desire to discuss existential, spiritual and/or religious concerns with their health care provider [3]. Furthermore, research shows that communicating about these issues, as part of medical care, is associated with an improved ability to cope with disease symptoms, better patient quality of life and increased mental and social wellbeing [3,4]. As a result, communication about existential, spiritual and religious aspects is viewed as an essential element of person-centered medicine [5]. In this research study, we shall use the term “existential communication” as a meta-concept that includes communication about broad existential aspects and potentially, but not mandatorily, communication about spiritual and religious aspects [6].

In the speciality of general practice attention to existential issues in the clinical encounter is highlighted as a central part of general practitioners’ professional and ethical responsibility [7]. However, several barriers have been identified to hinder communication about existential issues. These both include individual physician characteristics as well as contextual and organizational dynamics such as: a) personal insecurity, b) lack of education and training, c) lack of language, d) low self-awareness regarding existential and religious values, d) restricted time resources and general workload, and e) a predominantly one-dimensional biomedical focus on health problems and outcomes [8,9].

Researchers have suggested that offering opportunities for professional development regarding existential communication, e.g. through vocational training (VT) or continuing medical education (CME), is a feasible and effective method to increase health professionals’ confidence in providing this type of care [10]. However, there is no specific knowledge of how such initiatives towards enhancing existential communication can best be developed and structured in a general practice setting. We therefore aimed to develop a course programme in existential communication targeting GPs and to investigate the participants’ evaluations of the impact and significance of the course after attending. In progressively modelling a complex intervention through different research phases we expected to have generated the results needed to decide whether a randomized controlled design would be accurate for measuring the effect of the intervention at a later stage.

The UK Medical Research Council’s (MRC) framework for complex intervention research was used as a guide to course development and evaluation [11]. In the following Methods and Results sections we describe the development- and evaluation phases of the course under the following headings:

1. Development phase, 2. Feasilbility and piloting phase, 3. Evaluation phase and 4. Implementation phase. The first two phases are described under the Methods section whereas the last two sections are described under the Results section.

Methods

Development phase

The development phase included: identification of evidence (secondary research) and needs for further, explorative research (primary research), description of the theoretical framework of the course, and designing the intervention and deciding for types of evaluation.

Identifying the evidence and needs for primary research

No specific studies focusing on the development and evaluation of course programmes in existential communication in general practice were found when searching the databases Scopus, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO and using four groups of terms combined with AND: Existential, Curriculum, Cancer, General practice (the complete search string- and history can be obtained from the first author).

From a broader perspective, training curricula framed within the field of spiritual care (broadly understood as care that attends to existential, spiritual and religious patient needs) have been developed and implemented internationally for professionals in other health care sectors, mostly within palliative care [10]. We reviewed the existing evidence in order to establish if a VT/CME course could be expected to have a worthwhile effect. A number of studies concluded that training and education in communication regarding spiritual issues had a positive effect in terms of making health professionals feel better equipped to handle such issues [10].

The European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) and the International Society for Health and Spirituality (IGGS) surveyed their members in order to gain an overview of the current situation in spiritual care training in Europe [12]. Reviewing the great variety of spiritual care courses that were reported, the authors recommend that future courses consider an appropriate distribution between a) providing knowledge, b) developing attitudes, sensitivity and self-reflection and c) working on participants’ personal and professional skills while preparing them for spiritual care [12]. The authors also recommend developing courses that are adapted to the local society, taking cultural and religious variations into account.

In order to adapt these insights from the literature on spiritual care training to the local Danish society and general practice context, we supplemented the development of the course programme with primary, explorative research. Focus group interviews were conducted with GPs in order to investigate understandings among GPs of the existential dimension and of how and when the existential dimension was integrated in the interaction with patients [13]. Furthermore, we investigated barriers and facilitators to existential communication as perceived by GPs as well as their suggestions for educational initiatives [14]. In the focus group interviews, the GPs acknowledged knowledge deficits regarding patients’ spiritual and religious needs. Self-reflection, understood as providing the opportunity for scrutinizing own beliefs and values, was also suggested as an essential and productive learning activity highlighting the need for an increased awareness of how personal values affect professional practice. All the above results were used to develop the intervention. Furthermore, the GPs voiced a need for training tools that could guide them in communicating about existential issues and concerns. Consequently, we developed a question tool [15] that was incorporated into the final course curriculum.

Theoretical framework of the course

The theoretical base for the training course is to be found within the tradition of existential philosophy and psychology that deal with questions relating to the most basic questions of existence: the meaning of one’s being, freedom, isolation and death [16,17]. According to this framework, these conditions are not only inescapable givens of human existence, but also catalysts for existential distress and growth. To reach authentic and meaningful “being” the individual must actively seek to address and reflect on existential questions related to feelings such as meaninglessness, hopelessness, disruption, anger, loneliness, fear of suffering and death. Likewise, addressing and reflecting on the above existential questions, is said to be a critical process in the preparation of health professionals to care for others [18].

Constructing or finding meaning appears particularly important during illness and crisis, since the onset hereof breaks apart the comprehensible world and challenges former meaning orientations [19]. To gain a sense of meaningfulness and handle the changed existential condition, the person may need to orient her-/himself towards new or renewed meaning orientations to handle the changed existential condition. These new meaning orientations might encompass existential dimensions and perspectives including religious and/or spiritual ones.

Designing the intervention

The intervention was designed as a one-day VT/CME course (eight hours) for practising GPs and residentials in training to become GPs. The course comprised both theoretical and practical elements incorporated into the following three basic elements:

Theoretical input – providing knowledge of overall theoretical frames, patient concerns and needs as well as knowledge of the importance of existential communication within the doctor-patient relationship. The teaching was conducted by the first and last author, both of them having considerable experience as teachers in existential philosophy and psychology and religious/spiritual coping and meaning-making.

Reflection in groups as well as self-reflective exercises (e.g. “What is the existential to me?”).

Communication training on how to listen, how to ask questions that facilitate dialogue, how to help the patient formulate problems, needs and resources using the method of theatre improvisation [20] that allows going back and forth between the following circular steps: improvising a scene, reflecting together on what happened, playing the scene anew incorporating the feed-back and sharing reflections in plenum. Two professional actors initiated the scenes and engaged in temporal moment-to-moment interactions with the audience. Subsequently, the GPs were invited to take the role of either patient or GP, and the feedback from the audience was moderated by a facilitator.

Deciding on types of evaluations

According to intervention researchers within health science, the evaluation and implementation of an intervention can be strengthened by incorporating consideration of the social mechanisms and processes through which an intervention works [11]. We therefore decided to evaluate the intervention on a smaller scale using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods.

To evaluate the impact of the course quantitatively, we decided to use self-efficacy as outcome as it has been widely used for self-assessment of the outcome of communication skills training [21]. The construct of self-efficacy was introduced by the psychologist Albert Bandura [22] and refers to a person’s estimate of his/her ability to perform a specific task or behaviour successfully.

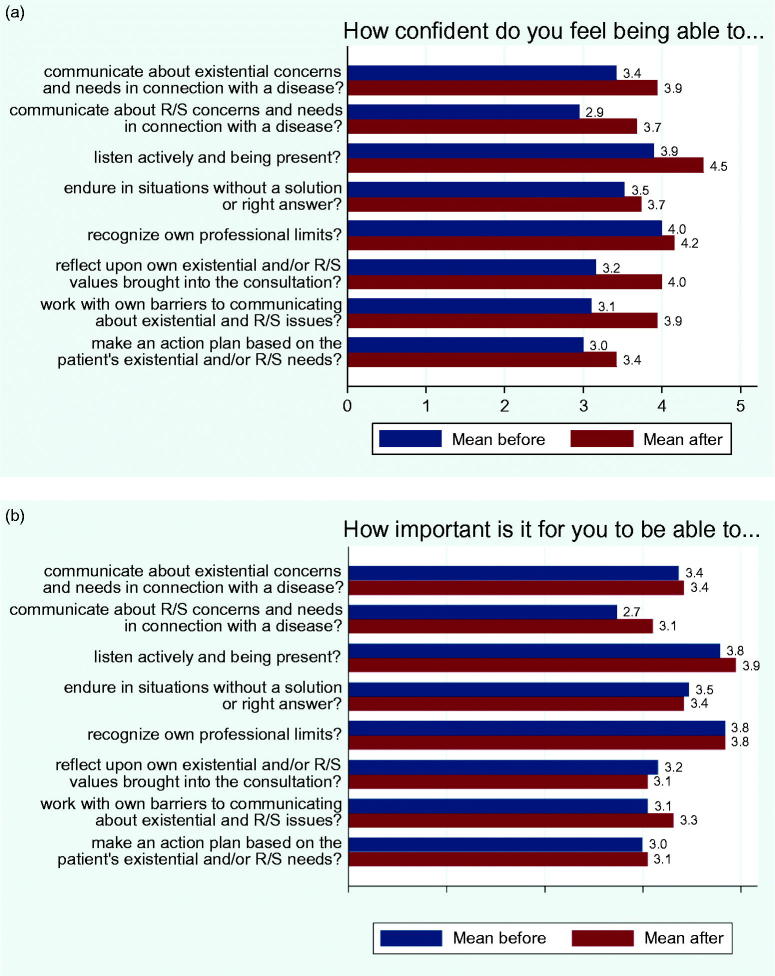

In constructing the questionnaire for measurement of self-efficacy regarding existential communication skills, we were inspired by Bandura’s guide for constructing self-efficacy scales [23] and a recently validated self-efficacy questionnaire (SE-12) measuring health care professionals’ clinical communication skills [24]. We further developed this questionnaire by adjusting the items to reflect the tasks and objectives of the course. Each question began with the words: “How confident do you feel being able to…” followed by eight different skills and competencies (listed in Figure 1(a)). Furthermore, in order to assess whether attending the course caused any changes in participants’ perceived importance of being able to manage each of the eight communication skills and competencies we added the following question: “How important is it for you to be able to…in your daily professional work?” (see Figure 1(b)). Ratings of the strength of self-efficacy and the perceived importance were made using a Likert scale from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (totally confident).

Figure 1.

(a) Changes in GPs’ self-efficacy regarding the eight listed communication skills and competences from before the course (T1) to immediately after the course (T2). (b) Changes in GPs’ perceived importance of the eight communication skills from T1 to T2.

With the aim of gaining a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences with attending the course, individual telephone interviews were conducted with participants. An interview guide with broad, open-ended questions and prompts were used to encourage participants to reflect on all stages of the intervention and to provide insight into what they experienced as bringing about change (if any).

Feasibility and piloting phase

Recruitment, participants and setting

The intervention was tested on a small scale (piloting). Participation was voluntary, in response to promotional material (a flyer) sent to randomly selected primary care clinics in the Southern Denmark Region and advertisements in a Facebook group for GPs in the region. Twenty participants attended the one-day training course at a regional conference venue (see Table 1). GPs were remunerated for participating in the course.

Table 1.

Demographic and professional characteristics of course participants.

| Baseline characteristics | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 19 (100) | |

| Age (mean age 49) | < 50 | 12 (63) |

| ≥ 50 | 7 (37) | |

| Gender | Male | 6 (32) |

| Female | 13 (68) | |

| Have you participated in communication courses after having completed your medical education? | Yes | 14 (74) |

| No | 4 (21) | |

| Don’t know | 1 (5) | |

| Years of experience as a GP | Is currently in education | 5 (26) |

| 1 year–less than 2 years | 0 (0) | |

| 2 years–less than 5 years | 1 (5) | |

| 5 years–less than 10 years | 5 (26) | |

| 10 years or more | 8 (42) | |

| Are you a believer? | Yes | 9 (47) |

| No | 7 (37) | |

| Don’t know | 3 (16) | |

| Nationality | Danish | 18 (95) |

| Danish and other nationality | 1 (5) |

The GPs were asked to answer the questionnaire electronically using SurveyXact before (T1) and just after the course (T2). The post-course questionnaire was expanded with ad hoc questions evaluating the participants’ perceived relevance of the course, the participants’ overall satisfaction with the content of the course, and the participants’ evaluation of their competencies in existential communication after having attended the course compared to before attending the course. Finally, participants were encouraged to write positive as well as negative criticism and to propose concrete changes for future courses.

Telephone interviews with fifteen participants were conducted up to four weeks after the course. The interviews lasted from twenty to sixty minutes and were transcribed verbatim by a secretary and validated by the first and last authors.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to clean data, determine if assumptions for parametric statistics were met, and to analyse the background variables (Table 1). The distribution for self-efficacy and perceived importance variables is given as mean standard deviation. The measurement at T1 was used as a baseline for comparisons with those made at T2. Paired samples t-tests were used to determine if before- and after-test scores differed significantly. P values ≤ .05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (v. 12.1.).

For the qualitative data analysis we used a hermeneutically inspired thematic content analysis [25]. Methodological rigor of the qualitative analysis was maintained through periodic debriefing with the research team.

Results

Evaluation phase

In the evaluation phase the following results from the quantitative and the qualitative evaluations were generated.

Quantitative evaluation

Nineteen course participants answered the questionnaire at T1 and T2. Demographic and professional characteristics of course participants are presented in Table 1.

Mean scores of self-efficacy at T1 and T2, respectively, are presented in Table 2(a). The mean scores of self-efficacy that increased the most were related to: The ability to communicate with patients about religious/spiritual (R/S) concerns, The ability to work with own barriers and The ability to reflect upon own existential/spiritual values brought into the consultation. Figure 1(a) illustrates the changes over time.

Table 2(a).

Mean scores of self-efficacy for (T1) and (T2).

| How confident do you feel being able to… | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) |

p Values |

Number of participants whose score after the course was |

||||||

| Questions | Before | After | t-test | One point less than before | The same as before | One point more than before | Two points more than before | Three points more than before |

| communicate about existential concerns and needs in connection with a disease? | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.6) | 0.001 | 0 (0) | 10 (53) | 8 (42) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| communicate about R/S concerns and needs in connection with a disease? | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.7 (0.7) | 0.002 | 1 (5) | 8 (42) | 6 (32) | 3 (16) | 1 (5) |

| listen actively and being present? | 3.9 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.6) | 0.000 | 0 (0) | 7 (37) | 12 (63) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| endure in situations without a solution or a right answer? | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.8) | 0.130 | 3 (16) | 10 (53) | 5 (26) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| recognize own professional limits? | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.6) | 0.165 | 3 (16) | 10 (53) | 6 (32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| reflect upon own existential and/or R/S values brought into the consultation? | 3.2 (0.9) | 4.0 (0.7) | 0.000 | 0 (0) | 7 (37) | 8 (42) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) |

| work with own barriers to communicating about existential and R/S issues? | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.6) | 0.000 | 0 (0) | 8 (42) | 7 (37) | 3 (16) | 1 (5) |

| make an action plan with the patient based on his/her existential and/or R/S needs? | 3.0 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.7) | 0.014 | 2 (11) | 8 (42) | 8 (42) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

The mean scores of perceived importance of the following eight questions at T1 and T2 are illustrated in Table 2(b). The GPs’ perceived importance of the eight communication skills did not change significantly from T1 to T2 except for their experiences of the questions: “Communication about R/S concerns” and “Active listening and being present”. Figure 1(b) shows the change from before the course (T1) to immediately after the course (T2).

Table 2(b).

Mean scores of perceived importance for the eight questions at (T1) and (T2).

| How important is it for you to be able to ….in your daily professional work? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants whose score after the course was |

||||

| Questions | One point less than before | The same as before | One point more than before | Two points more than before |

| communicate about existential concerns and needs in connection with a disease? | 4 (21) | 10 (53) | 5 (26) | 0 (0) |

| communicate about R/S concerns and needs in connection with a disease? | 1 (5) | 11 (58) | 6 (32) | 1 (5) |

| listen actively and being present? | 0 (0) | 16 (84) | 3 (16) | 0 (0) |

| endure in situations without a solution or right answer? | 3 (16) | 14 (74) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) |

| recognize own professional limits? | 2 (11) | 15 (79) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) |

| reflect upon own existential and/or R/S values brought into the consultation? | 4 (21) | 13 (68) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) |

| work with own barriers to communicating about existential and R/S issues? | 3 (16) | 8 (42) | 8 (42) | 0 (0) |

| make an action plan with the patient based on his/her existential and/or R/S needs? | 3 (16) | 12 (63) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) |

The participants’ evaluations of the training are presented in Table 3. A majority of the participants (74%) were “very satisfied” with the content of the course, and most participants (89%) assessed their competences in communicating about existential issues to be “better” than before attending the course.

Table 3.

Participants’ evaluations of the training.

| To what degree have you obtained new relevant knowledge? (N = 19) | N (%) |

| High degree | 7 (37) |

| Some degree | 10 (53) |

| Less degree | 2 (11) |

| Not at all | 0 |

| How satisfied were you with the overall content of the training course? (N = 19) | |

| Very satisfied | 14 (74) |

| Satisfied | 5 (26) |

| Less satisfied | 0 |

| Not at all satisfied | 0 |

| Compared to before you participated in the training course do you perceive your competences in communicating about existential issues to be (N = 19) | |

| Much better | 1 (5) |

| Better | 17 (89) |

| Unchanged | 1 (5) |

| Worse | 0 |

The responses to the open-ended questions were mainly positive with comments such as: “Inspiring course that motivates you to continue as a GP”, “Lovely to be able to share an interest in existential communication with colleagues” and “Fantastic course! Lovely to go beyond ‘factual knowledge’ and engage in self-reflection and theatre”. However, a few respondents commented that more time should be spent on communication training (the theatre improvisation method) and less time on theoretical knowledge.

Qualitative evaluation

The following themes were identified: one main theme: “understanding change” with two subthemes: a) “self-reflection and sharing with peers” and b) “increasing awareness and confidence”.

All course participants (n = 20) were invited to participate in the follow-up evaluation interviews within four weeks after the communication course. One participant did not respond to the invitation, four responded after the deadline given resulting in fifteen participants being interviewed by EAH.

In the accounts embedded in the theme “Self-reflection and sharing with peers”, the reflective course element (both individually and in groups) was much valued by the participants. Several participants recognized that, in order to be able to carry out existential communication with patients, one needs to be aware of” what one associates with the existential oneself”. Becoming aware of one’s barriers to communicating with patients about existential issues was also experienced as an important reflective endeavour. One participant expressed it as follows: “One has to become aware of one’s own barriers before being able to enter “the existential room”. As voiced by several of the participants, the reflective exercises prepared them for a more dedicated involvement in the subsequent communication training during the course.

In the accounts embedded in the theme “Increasing awareness and confidence”, the GPs described how attending the course raised their awareness of how religious and spiritual needs and resources might be experienced and lived by patients and of the significance of existential communication as a part of patient care. As a result of gaining more knowledge of existential, religious and spiritual patient needs, several participants mentioned that they had become better at “spotting the patients” in need of existential communication and at “picking up the patients’ cues”. Several of the participants talked about having gained communicative confidence through the communication training. Thanks to the theatre improvisation method, communicating with patients about religious and spiritual issues did not appear an impossible task anymore. One participant reported: “I experienced peace in doing it. I learned to endure in it. So, I felt that I left the course with considerable strength to carry it out myself”. Another participant said: “It’s okay! It’s okay! We are also capable of doing this. I can handle this as a physician”. Clearly, the boundaries of the GP’s role had been pushed for several of the participants, and existential communication had been reexamined with respect to its feasibility. In line with this, several participants reported that they had taken new actions in the time following the course and stepped out of their comfort zone.

Implementation phase

The results gained from the project raise issues as to what can be optimized in a future implementation phase. Several of the participants commented that the course could with advantage be longer by incorporating more time to communication training through theatre improvisation. Furthermore, participants demanded a more systematic integration of the supportive communication tool developed for the course [15] and providing them with a broader vocabulary and suggestions for key questions to ask.

Other ways to improve the intervention could involve a more specific focus on how to promote less solution-oriented approaches to the patient. The fact that self-efficacy in the ability to endure in situations without a solution or right answer did not increase considerably over time might indicate that more reflection on and training in enduring in meaningless and powerless situations are needed.

Discussion

Principal findings and relation to other studies

Both the quantitative and the qualitative results of this study show that the chosen design of the course with the three main elements (providing knowledge, reflective exercises and communication training) was positively evaluated by the GPs. Firstly, it raised their awareness of existential, religious and spiritual patient needs. Secondly, the course provided them with the opportunity to reflect individually and with colleagues on personal values and convictions and on how these could be included in their own everyday health care practice. Lastly, the course resulted in increased confidence in the GPs’ ability to carry out existential communication.

When looking at the quantitative results, we find that attending the course appears to have specifically effected an increase in the participants’ confidence in their ability to communicate with patients about religious and spiritual concerns and needs. Informed by studies showing improved self-efficacy and communication skills after training in existential support and spiritual care [10,26], increased scores of self-efficacy could be expected. However, given that the course participants are embedded in a highly secular culture where a large majority of people experience religious and spiritual orientations as either unfamiliar or relegated to the private realm [27], a non-significant increase in communication about these issues could also have been expected. Possibly, highlighting and demonstrating during the course that communication about religious and spiritual beliefs and values may be carried out meaningfully even though the patient’s beliefs and convictions seem foreign or irrational to the physician may have contributed to these results. The qualitative data supports this interpretation in that several participants voiced their relief when discovering that existential communication is not about having to “fix” the patients’ problems and concerns by saying the “right” things, but much more about non-verbal skills and competences such as active listening and being present with the patient. A significant increase in perceived importance regarding active listening and being present was also seen from T1 to T2.

The quantitative data furthermore showed a significant increase in perceived importance from T1 to T2 regarding communication about religious and spiritual concerns. Increases in communicative confidence are also reflected in the qualitative finding that the course was experienced as increasing awareness among participants and as having an “eye-opening” effect in terms of understanding how important communication with the GP about religious and spiritual concerns was to patients.

Both the quantitative and qualitative results reveal that the course promoted beneficial self-reflective processes. In the literature about curriculum development both within communication and spiritual care, it is argued that self-reflective practices are a necessary and an effective part of the training [10]. This is in line with our qualitative results indicating that the reflective practice of identifying, reflecting on and challenging personal barriers to this type of communication was perceived as a necessary prerequisite for existential communication. Research shows that low self-awareness regarding existential, spiritual and religious meaning orientations constitutes a large barrier [14,28]. It can be argued that low self-awareness is particularly characteristic of modern health professionals being prone to becoming socialized into a bio-medical culture that attends to disease, technology and biology, rather than meeting the patient emotionally and existentially [29]. Therefore, as several studies have shown, working with health professionals’ existential, religious and spiritual self-awareness through individual and group exercises is a prerequisite for health professionals wanting to gain confidence in existential communication.

According to Maguire and Pitceathly [30] and Bandura’s social learning theory [21], communication skills are most effectively taught and behavioral changes obtained in problem-focused training workshops in which other people’s behavior and their consequences are observed and cognitively processed. Based on these theories, the course was designed to ensure that knowledge acquired about concepts and patient needs together with reflection were immediately operationalized into improvised communication training. Our study indicated that the theatre improvisation method employed was a significant contributor to increases in communicative confidence.

The qualitative data revealed that the improvised theatre, in which GPs’ communication behavior was observed and reflected upon, resonated with real life clinical scenarios to a degree that the GPs felt prepared for real life clinical communication and were confident that they had acquired the needed skills (verbal and non-verbal) to carry out the task. Furthermore, the fact that the increase in the perceived ability to recognize own professional limits was non-significant might be due to the fact that the communication training had opened up to a broadening of the professional role and responsibility as reported in the qualitative data where the participants expressed that their concern over transgressing the profession’s area of expertise had been reduced as a result of attending the course.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study may be limited due to different types of bias. The course participants may want to show that the course activity was useful and improved their skills. Therefore, the GPs’ self-rating of self-efficacy can be considered a methodological weakness because of the risk of response bias. Furthermore, a course activity based on voluntary participation includes the risk of selection bias due to over-representation of participants open-minded to communication training as well as to themes relating to existential, spiritual and religious issues, although not necessarily confident in religious matters or religious themselves. A finding that support this interpretation is the lack of increase in perceived importance of most of the skills (see Table 2(b)). This could be interpreted as due to a response bias indicating that the GPs attending the course already had experienced and reflected on the importance of these existential issues.

The small number of participants in this study is another central shortcoming of the quantitative data since it reduces the possibility that an association shows to be statistically significant. Thus only tendencies can be drawn from the quantitative findings of this study. However, as mentioned earlier, we deliberately decided to test the intervention on a smaller scale in order to gain an understanding of contextual and situational issues surrounding the implementation and evaluation of the intervention, prior to a planned future large-scale RCT-study.

Practice implications

With this study, we add important knowledge to how confidence in the ability to communicate with patients about existential, religious and spiritual aspects can be increased. Devoting attention and time to this kind of VT/CME is important to patients and supports core medical values and ideologies such as patient-centered medicine and the bio-psychosocial disease model. Future research should include an evaluation in a randomised controlled trial of both long- and short-term effects on GPs’ self-efficacy and patient perspectives and outcomes, e.g. satisfaction and quality of life. Although cancer and general practice in Denmark have constituted our empirical starting point, the course has also been developed to outreach these boundaries in that it deals with broad and universal existential themes that play a central role to many individuals who suffer from serious or life-threatening illnesses or impairments.

Funding Statement

The study has received funding from the Danish Cancer Society, The Committee of Psychosocial Cancer Research [grant numbers: R114-A7131-14-S3], from The Novo Nordisk Foundation [grant number: 13986], from The Committee of Quality and Continuing Education Region of Southern Denmark [EU Appl. 02/15] and from The Foundation for General Practice [grant number: 15/2092].

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the GPs participating in this study for their time and interest.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest in connection with this paper. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. no.: 2015-41-3859) and all participants gave their written informed consent.

References

- 1. Henoch I, Danielson E.. Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: an integrative literature review. Psychooncology. 2008;18:225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee V, Loiselle CG.. The salience of existential concerns across the cancer control continuum. Pall Supp Care. 2012;10:123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kristeller JL, Rhodes M, Cripe LD, et al. Oncologist Assisted Spiritual Intervention Study (OASIS): patient acceptability and initial evidence of effects. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35:329–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. Jco. 2010;28:445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stewart M, Belle J, Weston W, McWhinney I, McWilliam C, Freeman T.. Patient-centred Medicine. Transforming the clinical method. Abingdon (UK): Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6. La Cour P, Hvidt NC.. Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. WONCA The European definition of general practice/family medicine. Wonca Europe 2012 Edition, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Slort W, Schweitzer BP, Blankenstein AH, et al. Perceived barriers and facilitators for general practitioner-patient communication in palliative care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2011;25:613–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vermandere M, Choi YN, De Brabandere H, et al. GPs’ views concerning spirituality and the use of the FICA tool in palliative care in flanders: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:718–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paal P, Helo Y, Frick E.. Spiritual care training provided to healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2015;69:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paal P, Leget C, Goodhead A.. Spiritual care education: results from an EAPC survey. Eur J Palliat Care. 2015;22:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Assing Hvidt E, Søndergaard J, Ammentorp J, et al. The existential dimension in general practice: identifying understandings and experiences of general practitioners in Denmark. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34:385–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Assing Hvidt E, Søndergaard J, Hansen DG, et al. ‘We are the barriers’: Danish general practitioners’ interpretations of why the existential and spiritual dimensions are neglected in patient care. Cam. 2017;14:108–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Assing Hvidt E, Hansen DG, Ammentorp J, et al. Development of the EMAP tool facilitating existential communication between general practitioner and cancer patients. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017;23:261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frankl V. Man’s search for meaning. Boston: Beacon Press; 1969/2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yalom ID. Existential psychotherapy. Newyork: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lauterbach SS, Becker PH.. Caring for self: becoming a self-reflective nurse. Holist Nurs Pract. 1996;10:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Park CL, Folkman S.. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Rev Gen Psych. 1997;1:115–144. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larsen H, Friis P.. Theatre, improvisation and social change In: Shaw P, Stacey R, editors. Experiencing risk, spontaneity and improvisation in organizational change: working live. London: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ammentorp J, Sabroe S, Kofoed PE, et al. The effect of training in communication skills on medical doctors’ and nurses’ self-efficacy: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psych Rev. 1977;84:191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales In: Pajares F, Urdan T, editors. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Newwork: Information Age Publishing; 2006. p. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Axboe MK, Christensen KS, Kofoed PE, et al. Development and validation of a self-efficacy questionnaire (SE-12) measuring the clinical communication skills of health care professionals. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data. Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. London: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henoch I, Danielson E, Strang S, et al. Training intervention for health care staff in the provision of existential support to patients with cancer: a randomized, controlled study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andersen PB, Lüchau P.. Individualisering og aftraditionalisering af danskernes religiøse vaerdier. [The individualization and detraditionalization of the religious values of the danes] In: Gundelach P, editor. Små og Store Forandringer Danskernes Vaerdier siden 1981 [Small and big changes the values of the danes since 1981]. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vermandere M, De Lepeleire J, Smeets LF, et al. Spirituality in general practice: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:749–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Coulehan J, Williams PC.. Conflicting professional values in medical education. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2003;12:7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maguire P, Pitceathly C.. Managing the difficult consultation. Clin Med (Lond). 2003;3:532–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]