Abstract

Background and Aims:

Analgesic effect of gabapentin and pregabalin is well-defined in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Postoperative pain after lumbar spine surgery limits the function of patients in the postoperative period, for which the search for ideal analgesic goes on. The aim of the present study was to compare pregabalin and gabapentin as a pre-emptive analgesic in elective lumbar spine surgeries.

Material and Methods:

In this randomized prospective study, 75 patients were allocated into three groups of 25 each. Group G, group PG, and group P received two capsules of gabapentin 300 mg each, two capsules of pregabalin 150 mg each, and two multivitamin capsules, respectively, with sip of water 1 hour before the expected time of induction of anesthesia. Time for requirement of first dose of rescue analgesia, reduction in postoperative pain score and total dose of rescue analgesic used in first 24 hours postoperatively, and side effects were compared.

Result:

Time for requirement of first dose of rescue analgesic in PG group was 180.12 min and in G group was 104.16 min, which was statistically significant. Both G and PG group had lower visual analogue scale (VAS) score in comparison to P group, which was statistically significant. Consumption of rescue analgesic was less in G and PG group in comparison to P group. Amount of rescue analgesic requirement were low in PG group in comparison to G group (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Though both study drugs had produced prolonged postoperative analgesia compared to placebo, pregabalin had better analgesic profile in postoperative period than gabapentin.

Keywords: Gabapentin, lumbar spine, pregabalin, surgery

Introduction

Pre-emptive analgesia is an antinociceptive therapy that prevents the central processing of afferent input responsible for postoperative pain and subsequently decreases the incidence of hyperalgesia and allodynia after surgery.[1] Many drugs and techniques have been used to produce analgesia which include epidural analgesia, local anesthetic infiltrations, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids, but each is associated with some side effects.

Gabapentin is a structural analogue of gamma aminobutyric acid. It acts by binding with α2-δ protein subunit of presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels in both central and peripheral nervous system which results in antinociceptive, antihyperalgesic, and antiallodynic properties.[2]

Pregabalin is a structural analogue of gamma aminobutyric acid but has a superior pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile.[3] It is more potent and more effective analogue of gabapentin. It is useful in the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain, postherpetic neuralgia, partial seizures, andgeneralized anxiety disorder.[4,5]

There were very few clinical studies available in the literature comparing analgesic efficacy of pregabalin and gabapentin as pre-emptive analgesic for postoperative pain management for the patients posted for spine surgery. Liu et al. in his recent meta-analysis of the preoperative use of gabapentinoids for the treatment of acute postoperative pain following spinal surgery concluded that preoperative use of gabapentinoids was able to reduce postoperative pain, total morphine consumption, and morphine-related complications following spine surgery. They opined that further studies should be done to determine the optimal dose and whether pregabalin is superior to gabapentin in controlling acute pain after spine surgery.[5] Primary aim of the present study was to comparethe time of requirement for first dose of rescue analgesia. The amount of rescue analgesia needed postoperatively in first 24 hours, postoperative VAS score, side-effects, and hemodynamic parameters were the secondary aim. We hypothesized that the pain would be less and requirement of first dose of rescue analgesic would be delayed in the pregabalin group than that in the gabapentin group.

Material and Methods

After approval from Institutional Ethical Committee, the study was conducted in 75 patients of ASA grade I and II of either sex and of age group between 25 and 70 years. All cases were scheduled for elective spine surgery which includes lumbar discectomy and spinal tumor surgeries under general anesthesia. Patients with epilepsy, impaired liver and renal function, history of drug or alcohol abuse, allergy to gabapentin or pregabalin, history of vertigo, and daily intake of corticosteroids were excluded from study. All patients were randomly divided into the following 3 groups using a computer-generated randomized chart and opaque sealed envelope technique. The anesthesiologist who administered the study drug was not involved in intra and postoperative monitoring and management.

Group-G: Received two gabapentin capsules 300 mg each with a sip of water 1 hour before the expected time of induction of anesthesia.

Group PG: Received two pregabalin capsules 150 mg each with a sip of water 1 hour before the expected time of induction of anesthesia.

Group-P: Received two placebo (multivitamin) capsules with a sip of water 1 hour before the expected time of induction of anesthesia.

Preanesthetic check-up was done and informed consent was obtained from all the patients on the day before surgery. They were physically examined and laboratory investigations were reviewed. VAS (0–100 mm) was explained to all the patients. Tab alprazolam 0.5 mg and tab ranitidine 150 mg was given as a premedication on the night before the day of the surgery. On the day of surgery, study drug was given orally 1 hour before the time of induction of anesthesia. In the operation theatre, baseline heart rate, oxygen saturation, and blood pressure were recorded. After insertion of a 18-G IV cannula, inj. glycopyrrolate 0.004 mg/kg, midazolam 0.04 mg/kg, and inj. fentanyl 2 mcg/kg was given intravenously. Preoxygenation was done with 100% oxygen for 3 minutes prior to induction. Induction was done with inj. propofol (1.5–2 mg/kg) and intubation was done after giving inj. vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg with appropriate sized cuffed endotracheal tube. Anesthesia was maintained with 66% N2O in oxygen with isoflurane (0.5% to 1% in vaporizer dial setting). Electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure, SpO2, heart rate, systolic (SBP), diastolic (DBP) and mean arterial pressure (MAP), end tidal CO2 concentration (EtCO2), temperature and bispectral index (BIS) was monitored. Fluids such as ringers lactate was administered at 60–80 ml/h. Intravenous paracetamol 15 mg/kg IV was given to all patients in group G, PG, and P approximately 30 min before the end of the surgery. Amount of blood loss and urine output was recorded intraoperatively. At the end of surgery, reversal was done with inj. neostigmine and inj. Glycopyrrolate, and the patients were extubated and shifted to postanesthesia care unit.

Immediately after shifting the patients to postanesthesia care unit, heart rate, respiratory rate, NIBP, VAS score, and sedation score were recorded. VAS and sedation scores were measured at each 1 hour for the first 4h, every 2h for the next 4h, 4 h upto 24 h.

Rescue analgesic (Inj. tramadol 1.5 mg/kg) was given when VAS score was more than 40 mm. Time to first rescue analgesic was recorded. Total dose of rescue analgesic needed in first 24 h of postoperative period was recorded. Sedation was assessed by Ramsay sedation scale. Any side effects such as dizziness, sedation, nausea, vomiting, headache, and respiratory depression were noted.

Sample size calculation was based on an initial pilot study involving 12 patients with “time needed for first rescue analgesic” as the primary end point of the study. Time to first analgesic request was 106.14 ± 11.35 min in group G,178.28 ± 12.64 min in group PG and 17.54 ± 12.15 min in group P. With an α error of 0.05 and power of the study (1− β) at 80%, to detect a minimum of 60 min difference in time needed for rescue analgesia between the three groups, the sample size was calculated to be approximately 23 in each group. Statistical analysis was done by using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson's Chi-square test. Parametric numerical variables were analyzed across the three groups using ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test as post hoc analysis between group variables. Data were analyzed using independent sample t-test as applicable. Nonparametric variables across the three groups were analyzed using Kruskal–WallisH-test between the three groups. All tests were two-tailed and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

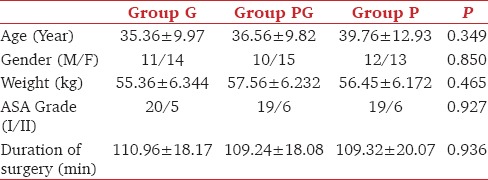

There was no statistically significant difference amongst the three groups regarding age, sex, weight, duration of surgery, and ASA status [Table 1]. There was no significant difference in hemodynamic parameters both intraoperatively and postoperatively among the groups.

Table 1.

Demographic data

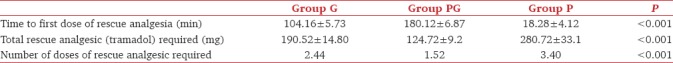

Demand for first dose of rescue analgesia was late in group PG than group G and group P. Similarly, group P required first dose of rescue analgesia earlier than other groups, which was statistically significant [Table 2]. Total dose of rescue analgesia requirement was highest in group P and lowest in group PG. Table 2 showed that total dose of rescue analgesic requirementin the postoperative period for 24 hours between the groups and their statistical comparison. Number of doses of rescue analgesic was lowest in pregabalin group compared with gabapentin and control group, and it was highest in control group which was statistically significant (P < 0.001)[Table 2].

Table 2.

Timing, number and total doses of rescue analgesia needed postoperatively

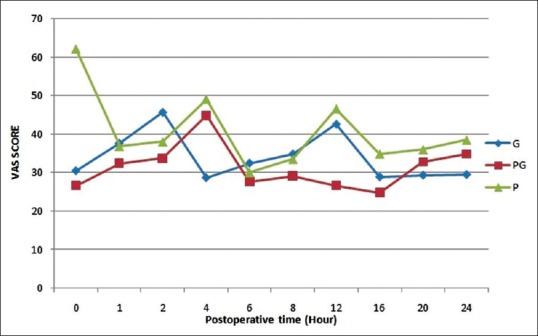

Mean VAS scores were low in pregabalin group in comparison to gabapentin and control group. Intergroup analysis revealed that both pregabalin and gabapentin groups had significantly lesser VAS scores in comparison to the control group [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Postoperative visual analogue scale score in different groups

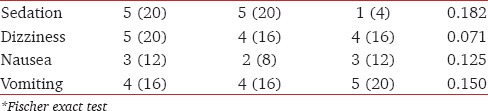

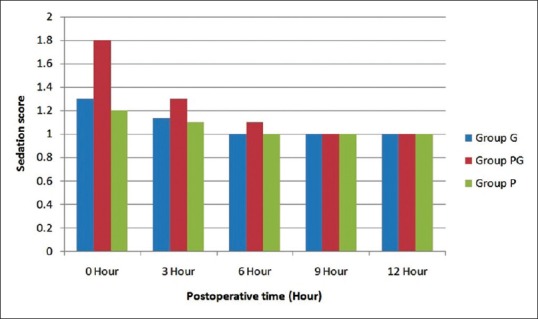

Table 3 showed various side effects that occurred in the three groups. There was no statistical significance between the groups for side effects (P > 0.05). Figure 2 showed the sedation score between the groups in the first 12 hours postoperatively. Pregabalin group had more sedation score than other two groups for the first 6 h. Similarly, gabapentin had higher sedation score than placebo group, however, there was no statistical difference in sedation score among the groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of incidence of side effects

Figure 2.

Postoperative sedation score in different groups

Discussion

Gabapentin and pregabalin are useful for treating neuropathic pain and may be beneficial in acute postoperative pain.[6] Our study concluded that though both drugs had produced prolonged postoperative analgesia; pregabalin (300 mg) had better analgesic profile in postoperative period than gabapentin (600 mg).

Pandey et al. in their study between gabapentin (300 mg) and tramadol (100 mg) in patients posted for laparoscopic cholecystectomy concluded that the pre-emptive use of gabapentin significantly decreases postoperative pain and requirement of rescue analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy which was similar to our finding.[7] Pandey et al. compared different doses of gabapentin for postoperative pain relief following lumbar discectomy and found that pre-emptive dose of 600mg gabapentin was an efficient analgesic compared to 300 mg of gabapentin; 900 mg and 1200 mg of gabapentinhave no added advantage. Therefore, we used 600 mg of gabapentin.[8]

Turan et al. in their study found that pain scores were significantly lower in the gabapentin (1200 mg) group compared to the placebo group in spinal surgery. They concluded that preoperative oral gabapentin decreased pain scores in the early postoperative period and reduced postoperative morphine consumption, there by decreasing morphine-related side effects.[9] Agarwal et al. in their study found that single preoperative oral dose of pregabalin 150 mg was effective in reducing postoperative pain and reduced fentanyl consumption in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[10] We had used pregabalin 300 mg in our study and concluded the same. Mishriky et al. in their study concluded that pregabalin provided better postoperative analgesia but more sedation and visual disturbances compared to placebo but there was no significant difference in 100 mg and 300 mg of pregabalin.[11] Saraswat et al. in their study between pre-emptive gabapentin (1200 mg) and pregabalin (300 mg) for acute postoperative pain after surgery under spinal anesthesiafound that gabapentin and pregabalin both provided prolonged postspinal analgesia, but pregabalin was more potent than gabapentin.[12] This was similar to our finding. Hill et al. conducted a study to compare 300 mg pregabalin and 400 mg of ibuprofen for dental pain and observed that pregabalin group had significantly longer duration of analgesia than the ibuprofen group.[13] Yilmaz et al. compared the efficacy of gabapentin and pregabalin in the treatment of neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury andfound no statistically significant difference between the two drugs.[14] Bafna et al. conducted a study to compare the effect of oral gabapentin and pregabalin with the control group for postoperative analgesia. They concluded that pre-emptive use of gabapentin 600 mg and pregabalin 150 mg orally significantly increased the duration of postoperative analgesia and reduced the postoperative rescue analgesic requirement in patients undergoing elective gynecological surgeries under spinal anesthesia.[15] Kim et al. studied the efficacy of pregabalin in septoplasty and suggested that the perioperative administration of oral pregabalin (300 mg) was an effective and safe drug to reduce postoperative pain in patients undergoing septoplasty.[16]

Ghai et al. performed a randomized controlled trial to compare pregabalin with gabapentin for postoperative pain in patients posted for abdominal hysterectomy. They concluded that a single dose of pregabalin 300 mg given 1–2 hours prior to surgery was superior to gabapentin 900 mg and placebo.[17] These finding were similar to ours. Zhang et al. evaluated the analgesic efficacy and opioid sparing effect of pregabalin in acute postoperative pain and concluded that perioperative pregabalin administration reduced opioid consumption and opioid-related adverse effects after surgery which was similar to our findings.[18] Alayed et al. examined the evidences in various databases and concluded that preoperative gabapentin not only decreased the visual analogue score but also reduced the incidence of nausea and vomiting.[19]

Burke et al. conducted a study to evaluate the use of perioperative pregabalin and concluded that perioperative pregabalin administration was associated with less pain and better functional outcomes 3 months after lumbar discectomy.[20] George et al.compared two doses of pregabalin (75 mg and 150 mg) in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy and concluded that low doses of pregabalin was not efficient in reducing opioid use postoperatively.[21] We also used 300 mg pregabalin in our study.

Sarakatsianou et al. in their study concluded that 600 mg of pregabalin had reduced the postoperative pain and consumption of opioids. They reported increased occurrence of dizziness which may be related to high dosage. Incidence of dizziness was less in our study as we had used lower dose.[22]

Balaban et al. in a randomized placebo-controlled study concluded that pregabalin (150 mg and 300 mg) reduced the postoperative pain and consumption of opioids after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which was similar to our findings.[23] Peng et al. compared low dose of pregabalin (50 mg, 75 mg vs placebo) and concluded that rescue analgesic consumption was similar in all three groups. Hence, higher doses must be used. Therefore, we used 300 mg pregabalin.[24]

Rajshree et al. studied 150 mg pregabalin and 900 mg gabapentin as pre-emptive analgesic in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. They found lower visual analogue scale (VAS) score, prolonged time of first rescue analgesic, and less opioid consumption in pregabalin group compared to gabapentin group. However, both gabapentin and pregabalin group had better analgesic profile than placebo group which was similar to our finding.[25] Sedation and dizziness were the two most common side-effects associated with gabapentin and pregabalin reported in almost all studies.

Conclusion

Pregabalin and gabapentin have a proven role in postoperative analgesia. Pregabalinhas a better analgesic profile and delays the time for requirement of first dose of rescue analgesic compared to gabapentin following spinal surgery. Both gabapentin and pregabalin can be used as pre-emptive analgesic in lumbar spine surgeries. There were no changes in the intraoperative hemodynamics, and the incidence of side-effects was not significant.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kissin I. Preemptive analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2000;99:1138–43. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kong VK, Irwin Mg. Gabapentin: A multimodal perioperative drug? Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:775–86. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Menachem E. Pregabalin pharmacology and its relevance to clinical practice. Epilepsia. 2004;45:13–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.455003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennet MI, Simpson KH. Gabapentin in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Palliat Med. 2004;18:5–11. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm845ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu B, Liu R, Wang L. A meta-analysis of the preoperative use of gabapentinoids for the treatment of acute postoperative pain following spinal surgery. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8031. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiippana EM, Hamunen K, Kontinen VK, Kalso E. Do surgical patients benefit from perioperative gabapentin/pregabalin? A systematic review of efficacy and safety. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1545–56. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000261517.27532.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandey CK, Priye S, Singh S, Singh U, Singh RB, Singh PK. Preemptive use of gabapentin significantly decreases postoperative pain and rescue analgesic requirements in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:358–63. doi: 10.1007/BF03018240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandey CK, Navkar DV, Giri PJ, Raza M, Behari S, Singh RB, et al. Evaluation of the optimal preemptive dose of gabapentin for postoperative pain relief after lumbar diskectomy: A randomized, double-blind placebo controlled study. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2005;17:65–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ana.0000151407.62650.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turan A, Karamanlioglu B, Memis D Hamamcioglu MK, Tükenmez B, Pamukçu Z, et al. Analgesic effects of gabapentin after spinal surgery. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:935–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200404000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal A, Gautam S, Gupta D, Agarwal S, Singh PK, Singh U. Evaluation of a single preoperative dose of pregabalin for attenuation of postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:700–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishriky BM, Waldron NH, Habib AS. Impact of pregabalin on acute and persistent postoperative pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2015:10–31. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saraswat V, Arora V. Pre emptive use of Gabapentine vs. Pregabalin for Acute Postoperative Pain after Surgery under Spinal Anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2008;52:829–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill CM, Balkenohl M, Thomas DW, Walker R, Mathe H, Murray G. Pregabalin in patients with postoperative dental pain. Eur J Pain. 2001;5:119–24. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yilmaz B, Yasar E, Koroglu Omac O, Goktepe AS, Tan AK. Gabapentin vs Pregabalin for the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain in patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Crossover Study. Turk J Phys Med Rehab. 2014;61:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bafna U, Khandelwal M, Rajarajeshwaran K, Verma AP. A comparison of effect of preemptive use of oral gabapentin and pregabalin for acute post operative pain after surgery under spinal anesthesia. J Anaesthesiol Clinical Phrmacol. 2014;30:373–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.137270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joon HK, Min YS, Sang DH, Jungbok L, Seung-KC, Hyo YK, et al. The efficacy of Preemptive Analgesia with Pregabalin in Septoplasty. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;7:102–5. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2014.7.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghai A, Gupta M, Hooda S, Singla D, Wadhera R. A randomized controlled trial to compare pregabalin with gabapentin for postoperative pain in abdominal hysterectomy. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:252–7. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.84097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Ho Ky, Wang Y. Efficacy of pregabalin in acute postoperative pain: A meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2011:454–62. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alayed N, Alghanaim N, Tan X, Tulandi T. Preemptive use of Gabapentin in abdominal hysterectomy: A systematic review and meta analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1221–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke SM, Shorten GD. Perioperative pregabalin improves pain & functional outcomes 3 months after lumbar discectomy. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1180–5. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cf949a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George RB, McKeen DM, Andreou P, Habbib AS. A randomized placebo controlled trial of two doses of pregabalin for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61:551–7. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarakatsianou C, Theodorou E, Georgopoulou S, Stamatiou G, Tzovaras G. Effect of pre emptive pregabalin on pain intensity and postoperative morphine consumption after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endos. 2013;27:2504–11. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balaban F, Yagar S, Ozgok A, Koc M, Gullapoglu H. A randomized placebo-controlled study of pregabalin for postoperative pain intensity after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24:175–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng PW, Li C, Farcas E, Haley A, Wong W, Bender J, et al. Use of low-dose pregabalin in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:155–61. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra R, Tripathi M, Chandola HC. Comparative clinical study of gabapentin and pregabalin for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:201–6. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.176409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]