Summary

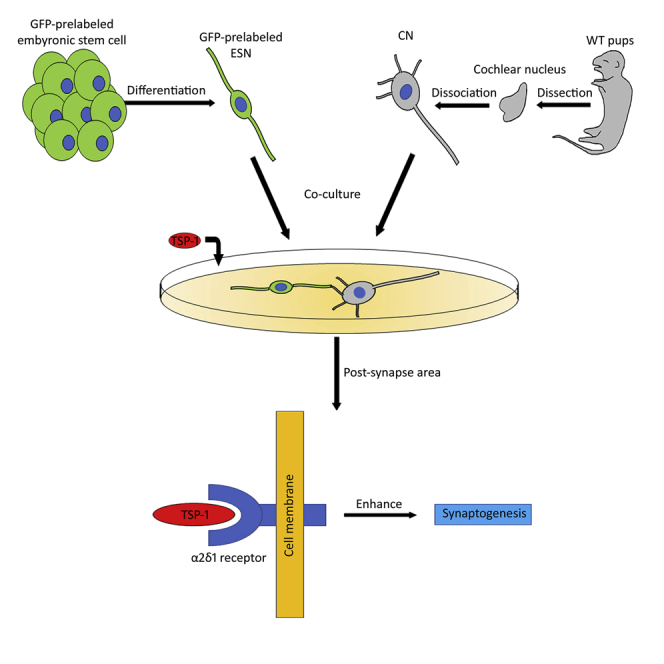

Integration of stem cell-derived neurons into the central nervous system (CNS) remains a challenge. A co-culture system is developed to understand whether mouse embryonic stem cell (ESC)-derived spiral ganglion neuron (SGN)-like cells (ESNs) synapse with native mouse cochlear nucleus (CN) neurons. A Cre system is used to generate Cop-GFP ESCs, which are induced into ESNs expressing features similar to auditory SGNs. Neural connections are observed between ESNs and CN neurons 4–6 days after co-culturing, which is stimulated by thrombospondin-1 (TSP1). Antagonist and loss-of-function small hairpin RNA studies indicate that the α2δ1 receptor is critical for TSP1-induced synaptogenesis effects. Newly generated synapse-like structures express pre- and post-synaptic proteins. Synaptic vesicle recycling, pair recording, and blocker electrophysiology suggest functional synaptic vesicles, transsynaptic activities, and formation of glutamatergic synapses. These results demonstrate the synaptogenesis capability of ESNs, which is important for pluripotent ESC-derived neurons to form functional synaptic connections to CNS neurons.

Keywords: α2δ1 receptor, auditory, cochlear nucleus, embryonic stem cell, regeneration, spiral ganglion neuron, synapse, thrombospondin-1

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Embryonic stem cell-derived neurons form functional synapses with CNS neurons

-

•

Thrombospondin-1 stimulates stem cell-based synaptogenesis via the α2δ1 receptor

-

•

A co-culture system is developed to study stem cell-based synapse formation

-

•

Stem cell-based synaptogenesis exhibits functional synapse features

Integration of stem cell-derived neurons (ESNs) into native cellular environment remains a major challenge. This research develops methods to study ESNs and brain nerve cells in the culture dish. ESNs form functional nerve connections with brain nerve cells in morphology, protein expression, and electrophysiology studies. The results are critical for stem cell-based neural pathway regeneration.

Introduction

In the neural system, signals perceived by the peripheral nervous system (PNS) are transferred to the central nervous system (CNS) via their connection nerves. In neurodegenerative diseases such as spinal cord injury (Ma, 2013) and hearing loss (Sheppard et al., 2014), the PNS and CNS neurons, as well as their connection nerves, are usually damaged. Since embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are pluripotent and can differentiate into ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm, stem cell-based approaches have been studied to replace damaged neurons (Hu et al., 2014, Liu and Hu, 2018). However, how to integrate stem cell-derived neurons into native nervous system remains a challenge. In this research, auditory system regeneration was investigated to address this issue.

In the auditory system, spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs) are PNS neurons that transfer auditory signals to the cochlear nucleus (CN) in the brainstem (Figure 1A). These neural components are usually damaged in hearing loss (Lin et al., 2011). In stem cell-based replacement, SGN-like cells have been generated in vitro using ESCs and tissue-specific stem cells (Li et al., 2016, Reyes et al., 2008). However, for newly generated cells to transfer auditory signals to the brainstem, proper neural connections must be established between new cells and native CN neurons, which at least includes connection, myelination, and tonotopic array of neurite outgrowths. This research focused on the synaptic connections of neurite outgrowths.

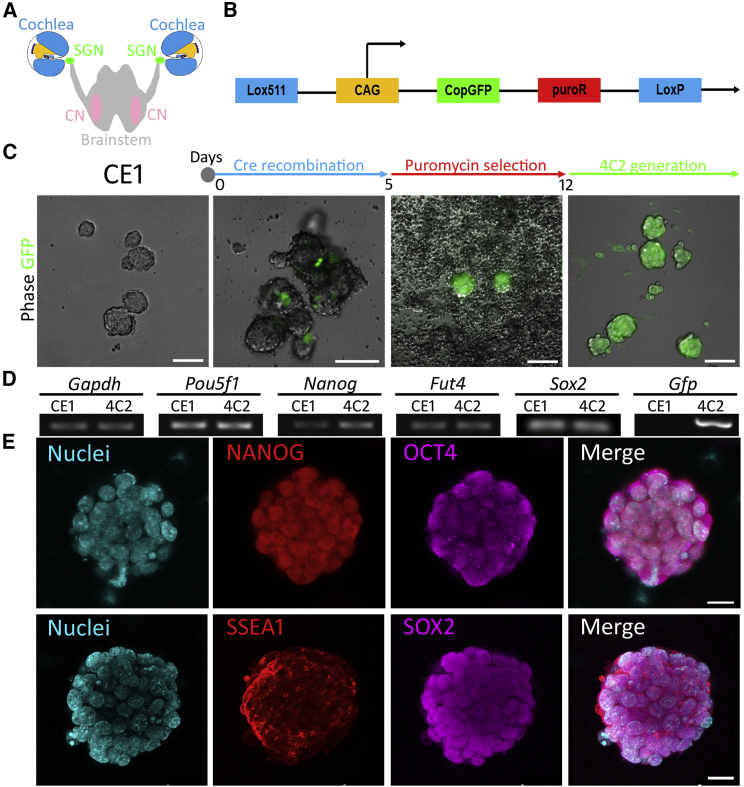

Figure 1.

Establishment and Evaluation of the 4C2 ESC Line

(A) Spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs), cochlear nucleus (CN), and their connections.

(B) The Cre plasmid for 4C2 ESC generation.

(C) Timeline of 4C2 cell generation: Cre recombination, puromycin selection, and 4C2 generation. Differential interference contrast (DIC) and epifluorescence microscopy images demonstrate 4C2 cell line establishment, which includes CE1, Cre recombination, puromycin selection, and 4C2 ESC generation.

(D) RT-PCR shows that both CE1 and 4C2 ESCs express Gapdh, Pou5f1, Nanog, Fut4, and Sox2. Gfp is detected in 4C2 cells but not CE1 cells. Original gel image in Figure S5.

(E) Immunofluorescence exhibits expression of OCT4, NANOG, SSEA1, and SOX2 in 4C2 cell colonies.

Scale bar: 100 μm in (C); 20 μm in (E).

Our recent report indicates that tissue-specific stem cell-derived neurons are able to form synapse-like structures with CNS neurons in a co-culture system (Hu et al., 2017). However, there are several weaknesses in our previous report. First, stem cells were obtained from SGN tissues, and the results may only apply to the auditory system. Second, since SGNs connect to the CN during normal development (Nayagam et al., 2011), SGN stem cell-derived neurons may already have a default development program to connect to CN neurons. Third, the electrophysiology of new synapses was not studied in our previous report. To address these issues, ESCs were used in this research, as ESCs are able to differentiate into all types of neurons, so the neural connections that result may be effective in many neural systems. In addition, pair recording excitatory post-synaptic current (EPSC) electrophysiology was used to evaluate the function of new synapses.

During development, SGNs are generated by neuroblasts derived from otic placodes/otocysts (Stankovic et al., 2004). Stepwise methods were used by previous studies to generate SGN-like cells from ESCs (Chen et al., 2012, Matsuoka et al., 2017). Since pluripotent 4C2 ESCs were used in this research, a stepwise method was used to guide 4C2 to become non-neural ectoderm, otic placode/otocyst, neuroblast, and eventually SGN-like cells, which is similar to the normal SGN development. Retinoic acid was selected for otic placode/otocyst induction, as it is critical for the development of the inner ear (Frenz et al., 2010). Since FGF signaling is essential for neuroblast and SGN development and maintenance (Alsina et al., 2004), a suspension culture system with the supplement of FGF2 was applied to induce neuroblast generation.

Stem cell-derived SGN-like cells have been co-cultured with hair cells or CN cells (Matsumoto et al., 2008, Matsuoka et al., 2017). However, signaling pathways critical for the synaptogenesis of ESC-derived neurons have not been ascertained. Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) is a member of TSP family proteins that demonstrates a critical role in promoting synaptogenesis of excitatory native CNS neurons (Lu and Kipnis, 2010). Our recent report suggests that TSP1 stimulates synapse formation of multipotent tissue-specific stem cell-derived neurons (Hu et al., 2017). However, it is unclear whether the synaptogenic effect of TSP1 applies to pluripotent ESC-derived neurons. Moreover, the underlying molecular mechanism of TSP1-induced synaptogenesis of stem cell-derived neurons remains obscure. In this research, we address these issues using pluripotent 4C2-derived neurons by defining the effects of the TSP1 membrane receptor using gain- and loss-of-function studies.

Results

Establishment of 4C2 Cells

Since CE1 ESCs have LoxP and Lox511 Cre-recombinase sites (Adams et al., 2003), a construct containing CAG-GFP-puroR flanked by LoxP and Lox511 was inserted into the CE1 genome (Figure 1B). To generate 4C2 cell lines, the CAG-GFP-puroR and EF1α-Cre pBS513 constructs were added to CE1 culture in the presence of Lipofectamine 2000. Many GFP-positive cells were found 24–72 hr after Cre recombination (Figure 1C), which proliferated and formed colonies. During puromycin antibiotic selection, GFP-expressing cells survived and continued to proliferate to form cell colonies, whereas non-GFP-expressing cells detached from the substrates and died (Figure 1C). After 7–10 days of puromycin treatment, all cells were GFP-positive (Figure 1C). RT-PCR showed that newly generated 4C2 cells expressed ESC genes Pou5f1 (encoding OCT4), Nanog, Fut4 (encoding SSEA1), and Sox2, which was similar to CE1 cells (Figure 1D). In addition, 4C2 expressed the GFP gene, which was not seen in CE1 cells. Immunofluorescence showed that 4C2 cells were immunostained by ESC proteins OCT4, NANOG, SSEA1, and SOX2 (Figure 1E). These results suggest that the GFP-expressing 4C2 cell line with typical ES features has been established.

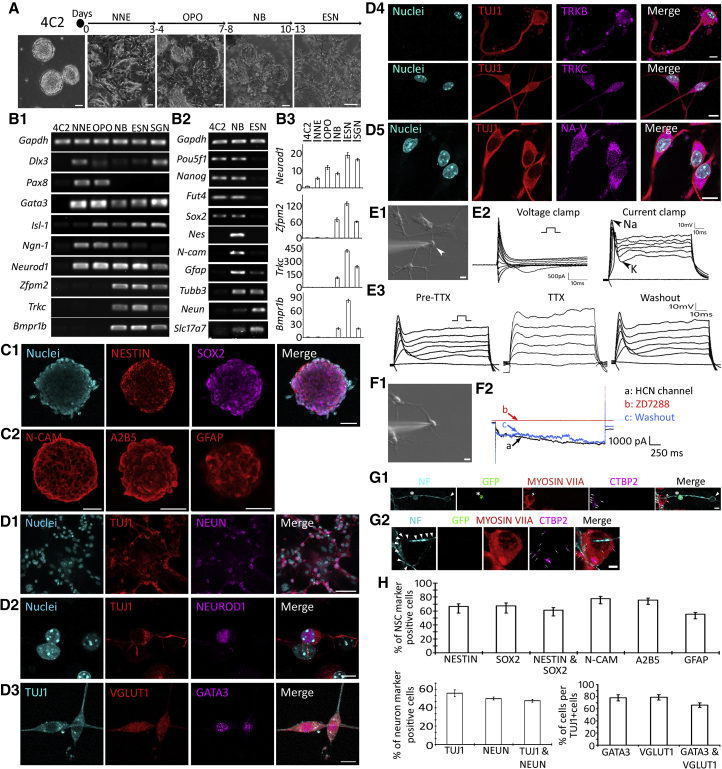

Neural Differentiation of 4C2 Cells

A stepwise method was used for neuronal differentiation (Figure 2A): induction into non-neural ectoderm (3–4 days), otic placode and otocyst (4–5 days), neuroblast (3–5 days), and ESC-derived SGN-like neuron (ESN) (3–6 days). To guide non-neural ectoderm and otic placode/otocyst formation, 4C2 cells were treated with retinoic acid for 7 days, and demonstrated monolayer cell morphology that was different from ESC colonies. Retinoic acid-treated cells expressed non-neural ectoderm marker Dlx3 (Feledy et al., 1999) and otic placode/otocyst markers Pax8 (Pfeffer et al., 1998) and Gata3 (Lillevali et al., 2006). These retinoic acid-treated cells were suspended in the suspension medium to form spherical cell clusters (Figure 2A), which expressed multiple neuroblast markers: Isl-1, Ngn-1, and Neurod1 (Figure 2B) (Fritzsch et al., 2002). In addition, spherical cells expressed general neural stem cell (NSC) genes Nes (encoding NESTIN), N-cam and Gfap, which were not observed in 4C2 cells (Figure 2B2). In the meantime, cell spheres continued to express ESC genes Pou5f1, Nanog, Fut4, Sox2, as well as other genes, including Tubb3 (encoding TUJ1), Neun, and Slc17a7 (encoding VGLUT1) (Figure 2B2). Immunofluorescence showed cell spheres were labeled by multiple NSC proteins: NESTIN, SOX2, A2B5, N-CAM, and GFAP (Figure 2C). Quantitative studies revealed that the majority of cells were immunostained with NSC markers NESTIN (66.44% ± 3.86%), SOX2 (67.39% ± 4.23%), A2B5 (75.79% ± 2.65%), N-CAM (77.85% ± 3.03%), and GFAP (55.38% ± 2.78%) (Figure 2H). These data suggest that 4C2-derived spherical structures are likely neuroblast spheres.

Figure 2.

Neuronal Differentiation of 4C2 ESCs

(A) The timeline for neural differentiation of 4C2 cells. Phase contrast images reveal the neural differentiation of 4C2 cells, which includes 4C2, non-neural ectoderm (NNE), otic placode and otocyst (OPO), neuroblast (NB), and ESC-derived SGN-like neurons (ESNs).

(B1) RT-PCR shows gene expression changes in 4C2 and derivatives. It is noted that SGN-specific genes Zfpm2a, Bmpr1b, and TrkC are expressed in ESNs and native SGNs (positive control). Original gel image in Figure S6.

(B2) RT-PCR reveals that 4C2 cells express pluripotent genes but not neural stem cell (NSC; Nes, N-cam, and Gfap) or neuronal genes (Tubb3, Neun, and Slc17a7). Original gel image in Figure S7.

(B3) Quantitative PCR shows SGN-specific genes Neurod1, Zfpm2a, Bmpr1b, and Trkc are expressed in ESNs and SGNs (positive control).

(C1 and C2) 4C2-induced spheres express NB proteins NESTIN, SOX2, N-CAM, A2B5, and GFAP in immunofluorescence.

(D1–D5) 4C2-induced ESNs express TUJ1/NEUN (D1), NEUROD1 (D2), VGLUT1/GATA3 (D3), TRKB/TRKC (D4), and NA-V (D5) in immunostaining.

(E1 and E2) DIC image shows a clamped 4C2-induced cell (arrowhead in E1). Whole-cell recording using a voltage clamp shows inward currents, and Na+ channel spikes (arrowhead in E2) are observed in response to injected currents in a current configuration.

(E3) Sodium channel spikes are observed in whole-cell recording using a current clamp, which are diminished in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM). The neuronal activities are recovered after TTX washout.

(F1 and F2) In a voltage clamp of ESNs, hyperpolarizing steps result in the development of a slow inward current (a, black arrow). This current is blocked by ZD7288 (b, red arrow), which is recovered after ZD7288 washout (c, blue arrow).

(G1) GFP-ESNs (asterisk) were co-cultured with dissociated wild-type postnatal day 3 mouse cochlear nucleus (CN) neurons and dissociated cochlear hair cells for 4–6 days. GFP indicates cells originated from 4C2 ESCs, whereas CN cells and hair cells are GFP negative. A bipolar GFP-ESN (asterisk) forms NEUROFILAMENT (NF)-positive connections with a native hair cell (MYOSIN VIIA positive; double arrowheads and a native CN neuron (arrowhead). The pre-synaptic protein CTBP2 puncta are observed in the hair cell (arrows).

(G2) Highly magnified z stack images of G1 show the hair cell that is connected by NF-positive neurites (arrowheads) express CTBP2 (arrows).

(H) Quantitative study for the percentage of NSCs and neuronal marker-positive cells. All positive cells were counted against DAPI-labeled cells.

Data shown in all panels represent eight pooled independent biological experiments. Scale bar: 50 μm in (A), (C1), (C2), (D1); 10 μm in (D2–D5), (E1), (F1), (G1); 5 μm in (G2).

4C2-derived neuroblast spheres were cultured in the medium containing 20 nM nerve growth factor (NGF) to guide neuronal differentiation (Zhang et al., 2011). RT-PCR showed expression of general neuronal genes Tubb3, Neun, and Slc17a7 (Figure 2B2) 3–6 days after induction, and more importantly SGN lineage genes Bmpr1b and Zfpm2 (Lu et al., 2011) (Figure 2B1). Quantitative PCR suggests that high expression of SGN lineage genes (Bmpr1b, Trkc, and Zfpm2) was observed in 4C2-derived neuroblasts and neuron-like cells, which was not detectable in the early stages (Figure 2B3). Immunofluorescence demonstrated expression of neuronal proteins TUJ1, NEUN, NEUROFILAMENT, GFAP, and NEUROD1 in newly induced cells (Figures 2D1, D2, and S1). Quantitative study revealed that 35%–45% of induced cells were neuronal marker-positive cells, including NEUN (37.39% ± 1.19%), TUJ1 (41.74% ± 2.74%), and NEUN and TUJ1 double-positive (35.57% ± 1.19%; Figure 2H). Since glutamate is used by SGN afferents to conduct auditory signals, anti-VGLUT1 antibodies were applied, which revealed that 65.95% ± 3.72% of TUJ1-positive cells were also VGLUT1 positive (Figure 2H). GATA3 is expressed in developing inner ear and usually used as a marker for otocyst-derived cells (Luo et al., 2013). GATA3 immunostaining study showed that 78.22% ± 4.96% of TUJ1-positive cells were double labeled by anti-VGLUT1 and anti-GATA3 antibodies (Figures 2D3 and 2H). Of VGLUT1-positive cells, 83.78% ± 2.32% are GATA3 positive. Since SGNs usually express TRKB and TRKC, anti-TRKB and anti-TRKC antibodies were applied to 4C2-induced cells, which demonstrated immunostaining of both TRKB and TRKC (Figure 2D4). Immunostaining shows that all derived neurons expressed CALRETININ (Figure S1D), indicating type I SGN lineage (Liu and Davis, 2014).

Immunofluorescence showed expression of sodium channel protein NA-V in TUJ1-positive cells (Figure 2D5). In patch clamp studies, 12 out of 22 neuronal-like cells demonstrated neuronal activities. It appears that cells of round or oval shape with distinct neurite outgrowths were cells that demonstrated typical neuronal activities in patch clamp studies (Figure 2E1). In a whole-cell patch clamp recording, the resting membrane potential of these cells was −58.73 ± 3.53 mV. In a voltage clamp configuration, the studied cells exhibited inward currents (Figure 2E2). Remarkable spiking activities were observed when the cells were stimulated using a current clamp setup (Figure 2E2). In 9 out of 12 studied cells, cells showed reduced activities in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX), which was recovered after TTX washout (Figure 2E2). In our previous report (Li et al., 2016), tissue-specific stem cell-derived neurons expressed HCN channels and a prominent Ih current that is shown in native SGNs (Mo and Davis, 1997). We thus explored this possibility in a voltage clamp configuration. Hyperpolarizing steps resulted in the development of slow inward relaxations that could be blocked by administration of an HCN channel-specific blocker ZD7288 (100 μM; Figures 2F1 and 2F2), which were recovered after ZD7288 washout. This experiment shows that 4C2-derived neurons expressed NA-V and HCN channels of native SGNs, suggesting that they share the electrophysiology features of native SGNs.

Since native SGNs connect to hair cells and CN neurons, 4C2-derived neurons were co-cultured with dissociated mouse cochlear hair cells and CN neurons. In co-cultures, 4C2-derived neurons formed connections with hair cells (expressing MYOSIN VIIA) and CN neurons (expressing NEUROFILAMENT, Figures 2G1 and 2G2), which is a feature of native SGNs. Further, C-terminal binding protein 2 (CTBP2, a pre-synaptic protein expressed in native hair cells) immunostaining was observed in hair cells, suggesting functional connections at the protein expression level.

The above assays suggest that 4C2-induced cells express many neuron/SGN genes, proteins, and electrophysiology activities. Therefore, these induced cells were defined as ESNs in this study.

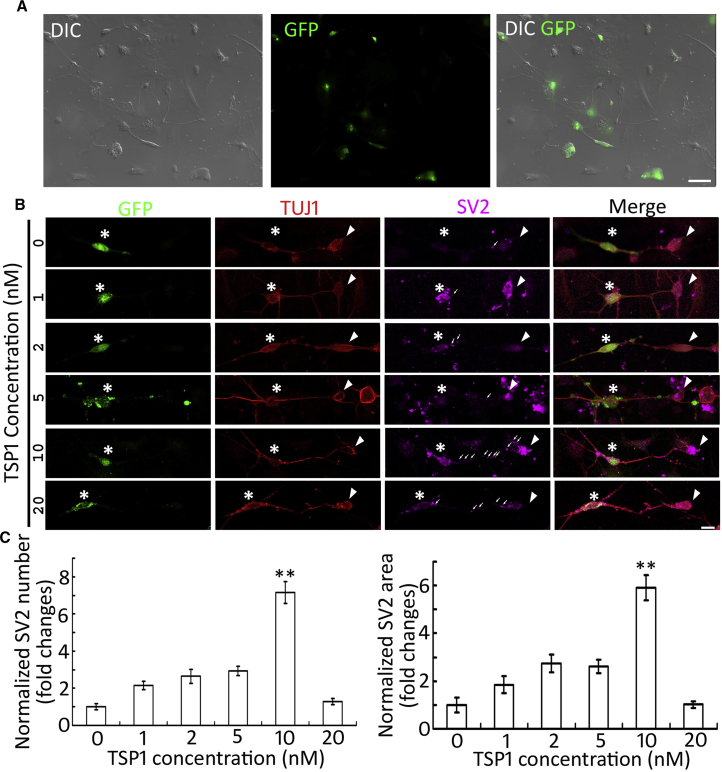

Stimulation of Neural Connection between ESNs and CN Neurons

Primary CN neuron culture was obtained using wild-type mouse CN tissues, followed by ESN co-culturing in serum-free medium containing NGF. To distinguish ESNs and native CN neurons, 4C2 cells and derivatives were pre-labeled by GFP (Figures 1C and S1C). The co-culture can be maintained in vitro for at least 4–6 days. In the co-culture, GFP-ESNs were ready to distinguish from wild-type mouse CN neurons by differential interference contrast (DIC) and epifluorescence microscopy (Figure 3A). Cellular connections were observed between ESN-ESN, CN-CN, and ESN-CN, in which ESN-CN connections were highlighted. Immunofluorescence showed that ESN-CN cellular connections were TUJ1 positive, indicating that neurite connections were formed between ESNs and CN neurons. The synaptic vesicle marker SV2 immunostaining revealed that a few SV2-expressing puncta were observed along ESN-CN connections (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

TSP-1 Stimulates Synaptic Vesicle Expression along ESN-CN Connections in Co-cultures

(A) GFP-ESNs were co-cultured with dissociated wild-type postnatal mouse CN cells for 4–6 days. GFP indicates cells originated from 4C2 cells, whereas CN cells are GFP negative by DIC and epifluorescence microscopy.

(B) TUJ1-positive connections are found between GFP-ESNs (asterisk) and wild-type CN neurons (arrowheads) in the presence of purified TSP1 protein (0–20 nM). SV2 puncta are found along ESN-CN connections (arrows).

(C) Quantitative study for SV2 puncta expression along ESN-CN connections suggests that 10 nM TSP1 exerts significant effects on SV2 puncta formation (mean ± standard error shown in the figure; ∗∗p < 0.01; ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test; see also Table S1).

Data shown in all panels represent eight pooled independent biological experiments. Scale bar: 50 μm in (A); 20 μm in (B).

To test whether TSP1 affects synaptogenesis in the co-culture, a series concentration of TSP1 (0–20 nM) was added to the co-culture for 4–6 days. Immunofluorescence showed that a few SV2 puncta were observed along connections between ESNs and CN neurons in 0, 1, 2, 4, and 20 nM TSP1 groups (Figure 3B). In contrast, significantly increased SV2-expressing puncta were detected in the 10 nM TSP1 group by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey post hoc tests (p < 0.01; puncta number, F(5,42) = 27.5234; puncta area, F(5,42) = 21.1483; SV2 puncta along connections were analyzed; Figure 3C and Table S1). This result suggests that 10 nM TSP1 may be the best concentration to promote SV2 expression along ESN-CN connections.

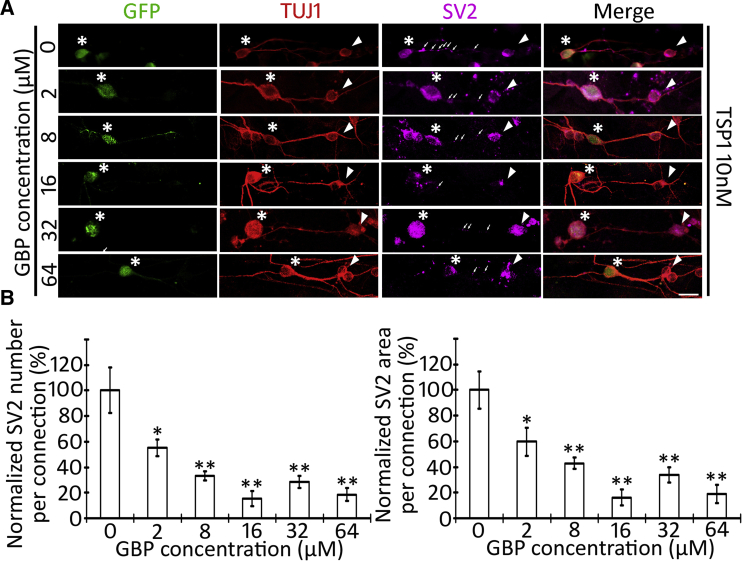

Next, we investigated the molecular mechanisms of TSP1-induced synaptogenesis of stem cell-derived neurons. The neural receptor for TSP1, α2δ1 (encoded by Cacna2d1, gene name α2δ1 in this study), is also the receptor for the anti-epileptic and analgesic drug gabapentin (GBP) (Griggs et al., 2015). To confirm the synaptogenesis effect of TSP1 and understand the underlying molecular mechanisms, the TSP1 antagonist GBP (0, 2, 8, 16, 32, and 64 μM) was added to ESN-CN co-cultures in the presence of 10 nM TSP1 for 4–6 days. SV2 immunostaining was used to evaluate the difference of synaptic vesicle formation among these groups. Immunofluorescence showed that many SV2 puncta were observed along connections between ESN and CN in the 0 μM GBP group (Figure 4A). However, very few SV2 puncta were observed along ESN-CN connections in 2, 8, 16, 32, and 64 μM GBP groups (Figure 4B). In a quantitative analysis, all GBP treatment groups exhibited significantly decreased SV2 immunostaining (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01; puncta number, F(6,65) = 9.6812; puncta area, F(6,66) = 10.498; ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test; SV2 puncta along connections were analyzed; Figure 4B and Table S2). These results indicate that the TSP1 antagonist GBP inhibits TSP1-induced synaptic vesicle formation in ESN-CN co-cultures.

Figure 4.

Gabapentin Antagonizes TSP1-Induced Synaptogenesis between ESNs and CN Neurons

(A) TUJ1-expressing connections are found between GFP-ESNs (asterisks) and wild-type CN neurons (arrowheads) in ESN-CN co-culture in the presence of 10 nM TSP1 and purified GBP protein (0–64 μM). The SV2 puncta (arrows) are localized along ESN-CN connections.

(B) Quantitative study of SV2 puncta along ESNs-CN connections demonstrates that expression of SV2 puncta seems to be inversely proportion to gabapentin supplementation, which is statistically significant (mean ± standard error shown in the figure; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01; ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test; see also Table S2).

Data shown in all panels represent eight pooled independent biological experiments. Scale bar: 20 μm in (A).

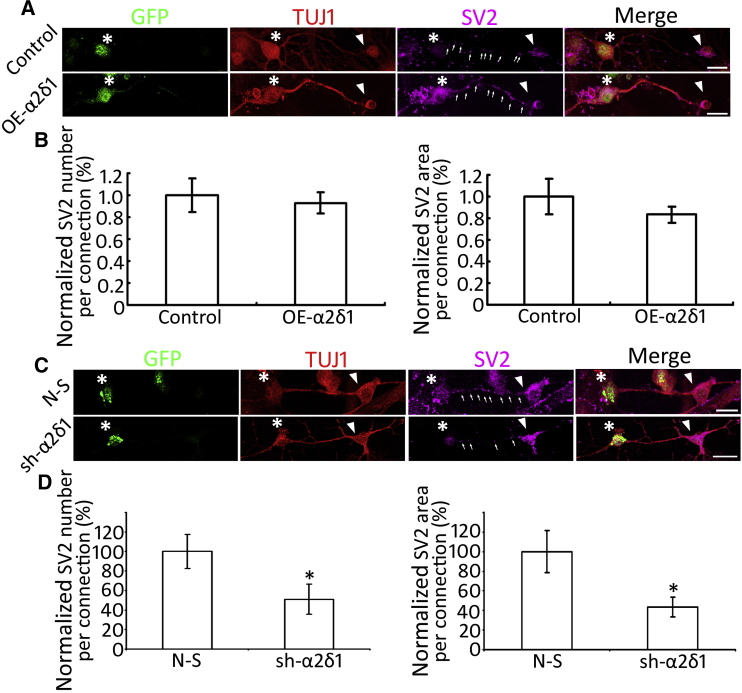

To further confirm the synaptogenesis effect of the α2δ1 receptor, gain- and loss-of-function studies were performed in ESN-CN co-cultures. First, α2δ1 was overexpressed in wild-type mouse CN neurons using Lipofectamine transfection (Lin et al., 2004) with a transfection efficiency of 13.23% ± 4.04%, which showed approximately 30-fold upregulation of α2δ1 expression in quantitative PCR (Figure S2). Quantification corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) study exhibited approximately 3-fold upregulation of α2δ1 protein expression in the α2δ1 overexpression group (Figure S2). GFP-ESNs were co-cultured with CN neurons overexpressing α2δ1 for 4–6 days in the presence of 10 nM TSP1. No significant difference in SV2 expression was observed between the control and overexpression groups (p > 0.05, Student's t test; SV2 puncta along connections were analyzed; Figures 5A and 5B). Next, a lentiviral small hairpin RNA (shRNA) probe targeting the mouse α2δ1 gene (sh-α2δ1) was developed (Figure S3A) and lentivirus containing the sh-α2δ1 construct was produced (Huang and Sinicrope, 2010). Similarly, lentivirus containing the non-silencing vector was generated as control. The efficiency of viral transduction is 14.20% ± 0.79%. Mouse CN tissues treated with sh-α2δ1 lentivirus showed approximately 40% downregulation of α2δ1 gene expression by qPCR (Figure S3C). Quantification CTCF study displayed approximately 40% downregulation of α2δ1 protein expression in the sh-α2δ1 group (Figure S2). sh-α2δ1-treated CN tissues were co-cultured with ESNs in the presence of 10 nM TSP1 for 4–6 days, which exhibited a significantly decreased amount of SV2 puncta in immunofluorescence compared with the non-silencing group (p < 0.05, Student's t test; SV2 puncta along connections were analyzed; Figure 5D). The loss-of-function study revealed a significant reduction in the number of synaptic vesicles in the sh-α2δ1 group, suggesting that the α2δ1 receptor may play an important role in TSP1-induced neural connections.

Figure 5.

Gain- and Loss-of-Function Assays of the α2δ1 Receptor

(A) TUJ1-positive connections are found between GFP-ESNs (asterisks) and wild-type CN neurons (arrowheads), as well as GFP-ESNs (asterisks) and wild-type CN neurons overexpressing α2δ1. SV2 puncta (arrows) are observed along ESNs-CN connections.

(B) Quantitative study reveals that there is no significant difference in SV2 puncta expression between the α2δ1 overexpression and control groups (mean ± standard error shown in the figure; p > 0.05, Student's t test).

(C) TUJ1-labeling connections are found between GFP-ESNs (asterisks) and wild-type CN neurons treated with either sh-α2δ1 (arrowheads) or non-silencing (N-S) vectors. SV2 puncta (arrows) are located along ESN-CN connections.

(D) Quantitative study reveals that remarkably less SV2 expression is observed along connections in the sh-α2δ1 group, which is statistically significant (mean ± standard error shown in the figure; ∗p < 0.05, Student's t test).

Data shown in all panels represent six pooled independent biological experiments. Scale bar: 20 μm in (A) and (C).

Characterization of New Synapses in Co-cultures

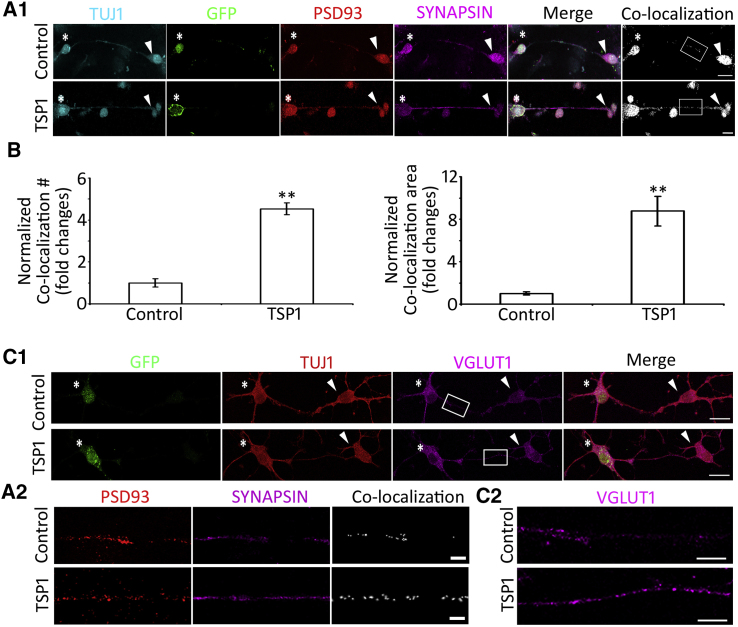

To characterize neural connections in co-cultures, pre- and post-synaptic markers, SYNAPSIN and PSD93 respectively, were used to determine whether TSP1-induced synapse-like structures expressed synaptic proteins. Immunofluorescence showed that both control and TSP1 treatment groups expressed SYNAPSIN and PSD93 in the soma and their neurite outgrowths. The expression of these synaptic proteins was analyzed along ESN-CN connections. Confocal microscopy-based co-localization exhibited apposition of pre- and post-synaptic proteins (Pearson's correlation 0.701 ± 0.025, Pearson's R test, Leica LAS AF Lite co-localization software; Figures 6A1 and 6A2), indicating that these pre- and post-synaptic proteins are co-localized. In the quantitative study, the TSP1 group showed significantly increased co-localization of PSD93 and SYNAPSIN puncta expression (p < 0.01, Student's t test, co-localization along connections was analyzed; Figure 6B). Since auditory afferents use glutamate for auditory signal transfer, newly formed synapse-like structures were tested by VGLUT1, a marker for glutamatergic synapses. Newly formed synapse formations were labeled by anti-VGLUT1 antibodies in control and TSP1 groups (Figures 6C1 and 6C2), suggesting that these synapse formations are likely glutamatergic.

Figure 6.

Synaptic and Glutamatergic Protein Expression in ESN-CN Connections

(A1) TUJ1-positive connections are observed between ESNs (asterisks) and CN neurons (arrowheads). Pre-synaptic marker SYNAPSIN and post-synaptic marker PSD93 are expressed in the control and TSP1 groups. Obvious apposition of SYNAPSIN and PSD93 are shown along ESN-CN connections by confocal microscopy-based co-localization in both groups (Pearson's correlation 0.701 ± 0.025, Pearson's R test, Leica LAS AF Lite Co-localization software).

(A2) High-magnification images display the puncta staining of PSD93 and SYNAPSIN, as well as their co-localization in the regions of interest along ESN-CN connections of control and TSP1 groups (white box in A1).

(B) Quantitative study of PSD93 and SYNAPSIN co-localization along ESN-CN connections demonstrates that more SYNAPSIN/PSD93 apposition is observed in the TSP1 group, which is statistically significant (mean ± standard error shown in the figure; ∗∗p < 0.01, Student's t test).

(C1) TUJ1-expressing connections are seen between GFP-ESN (asterisks) and wild-type CN neurons (arrowheads), which also express the glutamatergic marker VGLUT1 in the control and TSP1 groups.

(C2) High-magnification images show the puncta staining of VGLUT1 in the regions of interest along ESN-CN connections of both groups (white box in c1).

Data shown in all panels represent eight pooled independent biological experiments. Scale bar: 20 μm in (A) and (C).

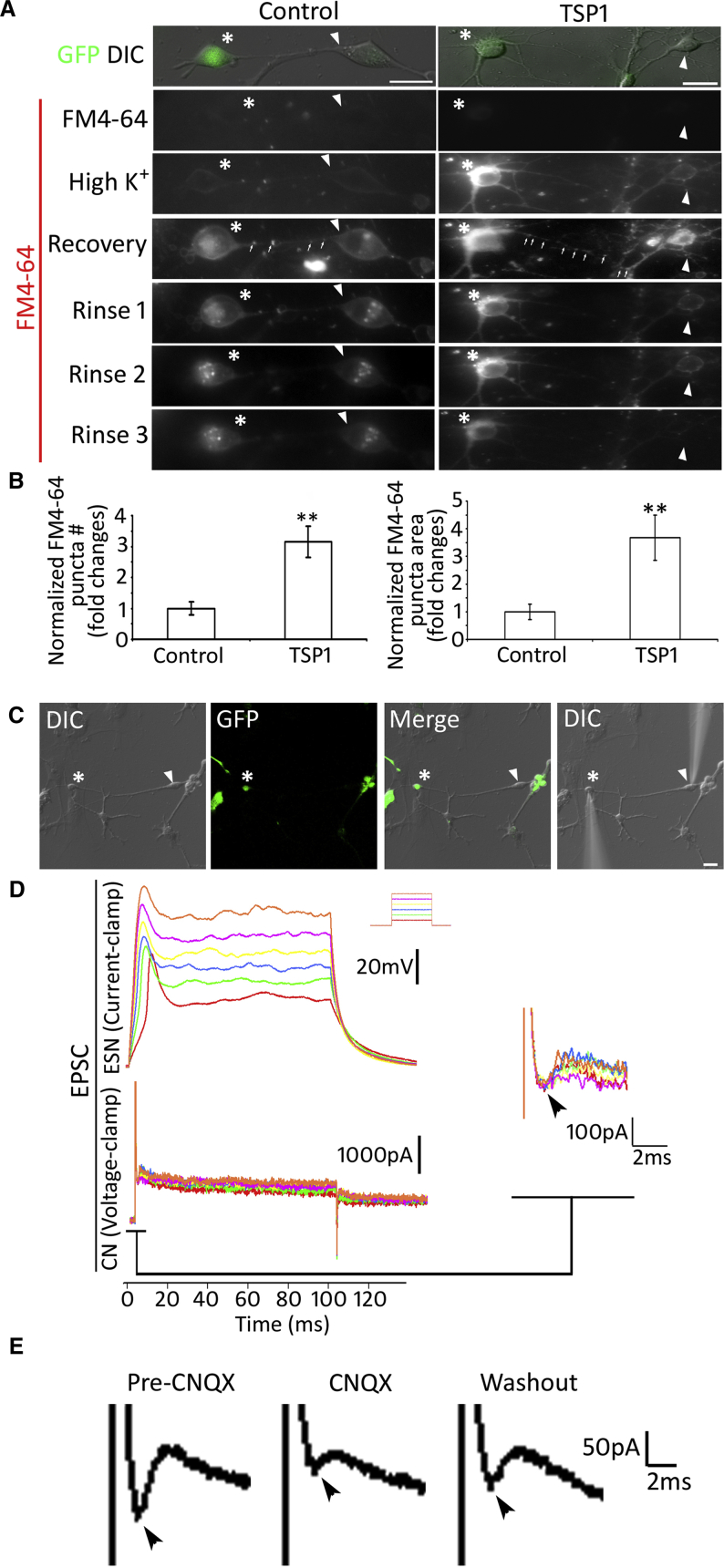

Synaptic vesicle recycling was assayed using a red fluorescence format FM dye FM4-64 (Li et al., 2009). In initial exposure to FM4-64 dye for 60 s, very few stained puncta were found in TSP1 and control groups (Figure 7A). In response to high potassium stimulation, obvious FM-stained puncta were observed in soma and along ESN-CN neurite outgrowths. During the recovery stage, the puncta along neurite connections remained distinct and consistent. Compared with the control group, significantly more puncta were observed in the TSP1 group (p < 0.01, Student's t test, FM4-64 puncta along connections were analyzed; Figure 7B). During the rinse stage, puncta along the neurites diminished gradually in both groups. Some FM dye staining remained in the soma at the end of the experiment (Figure 7A). This study suggests that synaptic vesicles along ESN-CN connections could be stained by the FM dye and transported to nerve terminals, indicating that the new synaptic vesicles are functional.

Figure 7.

Synaptic Vesicle Recycling Study and Electrophysiology for ESN-CN Connections

(A) ESN and CN neurons were co-cultured for 6 days in the presence or absence of TSP1, followed by FM4-64 staining. Connections are observed between GFP-ESN (asterisks) and wild-type CN neurons (arrowheads). No obvious FM staining was found when TSP1 and control group samples were incubated in FM4-64 for 1 min, whereas a dramatic increase of stained puncta was found in soma and axon in both groups following 90 s of high-K+ stimulation. In the recovery stage, FM-dye-labeled puncta (arrows) were found along ESN-CN connections in both groups. During rinse stages, FM staining along connections diminished gradually in both groups.

(B) Quantitative study of FM4-64 puncta along ESN-CN connections in the recovery stage demonstrates significantly more FM puncta in the TSP1 group (mean ± standard error shown in the figure; ∗∗p < 0.01, Student's t test).

(C) A connection was identified between a GFP-ESN (asterisks) and a wild-type mouse CN neuron (arrowheads) that were co-cultured for 6 days in the presence of TSP1.

(D) Pair recording electrophysiology was used to study the function of new synapses. The GFP-ESN was depolarized with 0–300 pA current for 200 ms. Responses of the CN neuron were simultaneously recorded, in which inward currents (arrowhead) were observed (enlarged on the right panel). After ESN stimulation, CN neurons usually demonstrate inward currents in a few milliseconds.

(E) In the presence of CNQX (5 μM), the inward current (arrowhead) recorded from CN neurons is reduced following ESN depolarization. After CNQX washout, inward current (arrowhead) of CN neurons partially recovers following ESN depolarization.

Data shown in all panels represent six pooled independent biological experiments. Scale bar: 20 μm in (A) and (C).

Pair recording of EPSC electrophysiology was employed to further determine the activities of ESN, CN neurons, and their transsynaptic activities. Both ESNs and CN neurons showed inward currents and action potentials in response to the voltage and current stimulation separately (Figure 7C). To study the transsynaptic function, pair recording was performed, in which GFP-ESNs were depolarized to observe the changes in CN neurons. It was observed that ESNs exhibited action potentials in response to depolarization, and CN neurons subsequently showed inward currents (Figure 7D). This study shows that excitatory signals were transferable from ESNs to CN neurons, indicating that new synapses were functional by electrophysiology. To determine whether the neural signal transfer is directional, we depolarized CN neurons to observe current changes in ESNs. However, no inward currents were observed from ESNs following CN depolarization (Figure S4), suggesting that ESNs were pre-synaptic and CN neurons were post-synaptic neurons. Since glutamate is the neurotransmitter of the afferent auditory system, we next explored the possibility of glutamatergic synapse formation. In the presence of the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)/kainate antagonist CNQX (6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, 5 μM), inward currents were not observed from CN neurons in response to ESN depolarization, which recovered following CNQX washout (Figure 7E), suggesting the formation of glutamatergic synapses.

Discussion

A stepwise neuronal generation method was employed to guide 4C2 ESCs to become non-neural ectoderm, otic placode/otocyst, neuroblast, and SGN-like ESN, which is similar to the normal development. ESNs expressed general neuronal markers TUJ1, NEUN, NEUROD1, and NEUROFILAMENT, as well as multiple auditory SGN-like genes and proteins (Bmpr1b, Zfpm2, TRKB, TRKC, and GATA3), indicating that they are likely SGN-like neurons. Moreover, ESNs exhibited neuronal-specific sodium channel protein NA-V by immunofluorescence, which was further confirmed by patch clamp electrophysiology. In addition, ESNs expressed HCN channels usually shown in native SGNs, which was reversely blocked by the HCN channel blocker ZD7288. Taken together, 4C2 ESCs were induced into functional ESNs that demonstrate SGN-like features.

Since bipolar SGNs relay auditory signals from cochlear hair cells to the CN in the auditory system, stem cell-derived neurons must be co-cultured with these two types of cells to test their authenticity. However, co-culturing of these three types of cells has not been reported previously. To address this issue, ESNs were co-cultured with dissociated mouse hair cells and CN neurons. It was observed that bipolar ESNs formed connections with dissociated hair cells and CN neurons simultaneously (Figure 2G), a typical feature of native SGNs. CTBP2 is a pre-synaptic protein that is usually expressed in native innervated hair cells. CTBP2 immunostaining was observed in hair cells that were connected to ESNs (Figures 2G1 and 2G2), suggesting functional connections at the protein expression level. These studies suggest that ESNs are bipolar neurons that are able to form neural connections with native hair cells and CN neurons.

TSPs are a family of multimetric extracellular matrix glycoproteins that play a variety of roles in regulating cell behavior, including modulating synapse formation and activity via the α2δ1 receptor (Eroglu et al., 2009). TSP family proteins are found to stimulate synaptogenesis and neurite outgrowing of human umbilical tissue-derived cells (Koh et al., 2015). Our recent report shows that TSP1 stimulates synapse formation of tissue-specific stem cell-derived neurons (Hu et al., 2017). However, it is obscure whether TSP1 stimulates synapse formation of pluripotent ESC-derived neurons. To address this issue, TSP1 was applied to ESN-CN co-culture. It was found that, compared with controls, TSP1 promotes SV2 puncta formation between ESN and CN neurons. Further, the synaptogenic effect of TSP1 is concentration dependent. These results suggest that TSP1 may be involved in synaptogenesis between pluripotent ESC-derived neurons and native CNS neurons.

To understand the molecular mechanism of synapse formation of ESNs, the α2δ1 receptor (the neuronal receptor of TSP1) was investigated. The competitive antagonist GBP significantly reduces TSP1-induced synapse formation between ESNs and CN neurons, which is likely due to its powerfully binding to the α2δ1 receptor to antagonize TSP1-α2δ1 interaction, and subsequently affects TSP1-induced effects. To further confirm the synaptogenic role of the α2δ1receptor, gain- and loss-of-function studies were performed. Overexpression of α2δ1 in CN neurons did not significantly stimulate synaptogenesis in ESN-CN co-cultures. The reason for this insignificant change is complicated but it may be related to relatively high expression of α2δ1 in wild-type CN tissue that may have reached a “saturated” level of α2δ1 effects. However, in the loss-of-function study, α2δ1 silencing in CN neurons significantly decreases synaptogenesis in ESN-CN co-cultures. These results suggest that the α2δ1 receptor is critical for TSP1-induced synaptogenesis of stem cell-based co-cultures.

The newly generated synapses exhibit a variety of synaptic properties. The ESN-CN connections express synapse vesicle protein SV2, the pre-synaptic protein SYNAPSIN, and the post-synaptic protein PSD93. Confocal microscopy-based co-localization assay suggests apposition of pre- and post-synaptic proteins. Excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate is used by SGNs to conduct sound signals. Immunofluorescence showed VGLUT1 staining along the new ESN-CN connections, suggesting that new connections may express VGLUT1 for possible glutamate conduction. Two settings were applied to examine the function of new synapses. In the synaptic vesicle recycling assessment, ESNs and CN neurons were labeled by FM dye in response to high potassium stimulation, and stained vesicles moved to the nerve terminals during the recovery and rinse stages, suggesting that new neural connections may possess functional synapse vesicles. In pair recording of EPSC electrophysiology, CN neurons showed inward currents in response to depolarization of ESNs, suggesting that depolarized ESNs transfer the neural signals to CN neurons via their connections. Interestingly, inward currents were not observed from ESNs following CN neuron depolarization, indicating that neural signal transfer is directional and that ESNs are pre-synaptic and CN neurons are post-synaptic neurons. The AMPA blocker test demonstrated that EPSCs were reversely blocked by CNQX, which suggests that new synapse formations are glutamatergic. These pair recording functional experiments reveal the transsynaptic functionality of newly generated connections between ESNs and CN neurons.

In summary, ESC-derived ESNs form neural connections with native CN neurons in vitro. These new neural connections exhibit the properties of functional synapses. TSP1 stimulates synaptogenesis between ESNs and CN neurons via the α2δ1 receptor. These results suggest that pluripotent ESC-derived ESNs are able to form synapses with native CN neurons, which is a critical step for integration of these ESNs into the native auditory system to rebuild the auditory circuit. Since pluripotent ESCs are used in this study, these results may be applicable to the other neural systems. These discoveries may suggest the possibility of developing novel strategies to utilize pluripotent ESC-derived neurons to replace damaged PNS neurons to reconnect to the corresponding CNS neurons for the treatment of a variety of peripheral neurodegenerative diseases.

Methods

Generation of 4C2 Cells

The 4C2 plasmid was constructed by inserting the fragment containing the CAG-CopGFP-PuroR construct using unique flanking restriction enzyme subcloning (Figure 1B). CE1 cells were maintained in the ESC culture medium (45% DMEM high glucose [Hyclone], 45% DMEM/F12 GlutaMAX, 10% knockout fetal bovine serum [FBS], 1% minimum essential medium [MEM], non-essential amino acids [NEAA], 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol [2-ME]; all from Invitrogen), and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF; 1,000 unit/mL, Millipore). The CAG-CopGFP-PuroR construct and pBS513-EF1α-Cre plasmid (Addgene) were added to the CE1 ESC culture in the presence of Lipofectamine 2000 for 2–4 hr. Puromycin (0.7 μg/mL) was added to the cell culture for antibiotic selection for 7–10 days to obtain pure GFP-expressing 4C2 cells.

Neural Differentiation of 4C2 Cells

4C2 cells were dissociated with TryplE (Invitrogen) and cultured in LIF-free ESC culture medium for 10 hr. All-trans retinoic acid (10−7M, Sigma) was added to the culture medium for 7–8 days, and cells were passaged using TryplE at 60%–70% confluence, followed by suspension culture (97% DMEM/F12 GlutaMAX, 1% N2, 2% B27, 55 nM 2-ME, 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor, and 20 ng/mL FGF-2; all from Invitrogen) for 3–5 days for NSC sphere formation. For neuronal differentiation, cell spheres were dissociated with TrypIE and seeded in the differentiation culture medium (45% Neurobasal, 45% DMEM/F12 GlutaMAX, 10% FBS, 55 nM 2-ME, and 20 ng/mL NGF) for 3–6 days.

Co-culture of ESN-CN and ESN-Hair Cells-CN

The care and use of the animals have been approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Postnatal day 3 mouse cochlear hair cell epithelium and CN tissues were dissected, dissociated with trypsin (Gibco), and cultured in the differentiation culture medium overnight. 4C2-induced NSCs were dissociated with TryplE, followed by seeding into culture wells containing either dissociated CN tissues only or dissociated CN tissues together with dissociated hair cell epithelium in the co-culture medium (50% DMEM/F12 GlutaMAX, 48% Neurobasal medium, 1% N2, 55 nM 2-ME, 0.1% Pen/Strep, and 20 ng/mL NGF) for 4–6 days. Purified TSP1 proteins (0–20 nM) (R&D Systems) were added to co-cultures to test the effect of TSP1. In the antagonist study, 0–64 μM purified GBP proteins (R&D) were supplemented to the co-culture medium. Co-cultures were observed and fixed for immunofluorescence and analyzed at the end of the experiment.

Overexpression and Silencing of the α2δ1 Gene

The plasmid containing the mouse α2δ1 gene (Lin et al., 2004) (Addgene) was added to the CN primary culture in the presence of Lipofectamine LTX reagent (Invitrogen) for 24 hr, followed by 0.4 mM hygromycin (R&D) antibiotic selection for 24–48 hr. Samples of CN tissues overexpressing α2δ1 were collected for RT-PCR study. The co-culture containing ESNs and CN overexpressing α2δ1 was set up as above.

Advanced shRNA design algorithms were used by the manufacturer (Sigma) to produce the shRNA probe targeting the mouse α2δ1 gene. The sh-α2δ1 was subcloned into a pSIH vector (Huang and Sinicrope, 2010) (Addgene) using unique flanking restriction enzymes. Viral production was carried out according to the protocols approved by the local biosafety committee. Lentivirus was generated by HEK293 cells using packing plasmids pMD2.BSBG, pMD2Lg/pRRE, and pRSV-REV. The non-silencing plasmid and lentivirus were generated accordingly. Lentivirus containing either sh-α2δ1 or non-silencing constructs was added to the CN culture in the presence of Polybrene (10 μg/mL, Thermo Fisher) for 24 hr, followed by 5 μg/mL puromycin antibiotic selection. After 24–48 hr, the medium was changed to the co-culture medium and ESNs were seeded for co-culture.

RNA Extraction, RT-PCR, and Real-Time qPCR

Total RNAs of CE1, 4C2, retinoic acid-treated 4C2 (day 3 for non-neural ectoderm and day 7 for otic placode/otocyst), neuroblast spheres (day 3–5 in suspension), induced ESNs (day 3–6 for induction), and postnatal day 3 Swiss Webster mouse SGNs were extracted by RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), followed by cDNA conversion using a QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturers' protocols. A thermal cycler (Eppendorf) was used for RT-PCR with GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega) with primers listed in Table S3. PCR products were electrophoresed and imaged using a ChemiDoc-It imaging system (UVP). A Bio-Rad CFX system was applied for qPCR using SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad; n = 3). The mean of quantification cycle (Cq) was calculated by Bio-Rad CFX Manager software using a regression mode. The relative expression levels of studied genes were delta/delta Cq values normalized with internal control gene Gapdh.

Immunofluorescence

After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, cell samples were treated with PBS containing 5% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were incubated in primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, followed by corresponding secondary antibodies incubation at room temperature for 2 hr. Primary and secondary antibodies are listed in Tables S4 and S5. DAPI (Invitrogen) was used to label all nuclei. Samples were observed and imaged by Leica 3000B epifluorescence microscopy and/or Leica SPE confocal microscopy.

FM4-64 Synaptic Recycling Study

ESN-CN co-culture samples were treated with either 10 nM TSP1 or DMEM/F12 GlutaMAX (control) for the synaptic recycling assay using previous methods (Hu et al., 2017). FM4-64 (Invitrogen) was diluted to 10 μM in Tyrode's solution. Co-cultures were incubated in FM4-64 solution for 60 s, followed by 90 s of high-potassium solution. Samples were recovered in FM4-64 solution for 15 min. The dye was rinsed with ice-cold HBSS every 3 min for 4–6 times. Samples were imaged by Leica DMi8 epifluorescence microscopy.

Electrophysiology

Co-culture samples were studied in a recording chamber on the stage of a Leica DM 6000 FS microscope containing extracellular solution maintained at 30°C ± 1°C (in mM: 144 NaCl, 5.8 KCl, 0.7 NaH2PO4, 0.9 MgCl2, 1.3 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 5.6 D-glucose. pH 7.4, 320 mOsmol/kg). GFP-ESNs were visualized and targeted for recording based upon their morphology and GFP labeling; wild-type CN neurons were visualized and targeted for recording by their morphology. Electrical signals were recorded using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and a Digidata 1550 digitizer under control of the pCLAMP 10 software (all from Molecular Devices). Recording pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass using a horizontal puller (Sutter Instrument) to give resistance ranging from 3 to 8 MΩ when filled with intracellular recording solution containing (in mM) 135 K-gluconate, 3.5 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 4 Na2ATP, 5 EGTA, and 5 HEPES, and a pH of 7.2–7.4 in voltage and dynamic clamps. Junction potentials were applied offline during analysis. For the voltage clamp, voltages ranging between −60 mV and +20 mV in 10 mV increments with a holding potential of −60 mV were delivered to the cells. For the current clamp, cells of interest were stimulated by currents (−50 to +300 pA in 50 pA increments). To study HCN channels, clamped cells were hyperpolarized from −60 mV to −120 mV for 1–2 s in the absence or presence of HCN blocker ZD7288 (100 μM, Tocris). The protocol was repeated after ZD7288 washout. For EPSC study, connections between GFP-ESNs and wild-type CN neurons were identified. The GFP-ESNs were depolarized by currents (−50 to +300 pA in 50 pA increments), and inward currents of wild-type CN neurons were simultaneously recorded for 200 ms. The protocol was repeated in the presence and absence of an AMPA/kainate blocker CNQX (6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, 5 μM, Alomone lab).

Quantification Study and Statistical Analysis

For this research, samples for statistical analyses were collected from at least 3–5 independent experiments. Cells were analyzed and counted by the ImageJ software (NIH) using the cell counter plugin module. SV2 puncta were analyzed using a previously reported method (Hu et al., 2017, Li et al., 2016). Briefly, the number and area of SV2 puncta along ESN and CN neuron connections, which was determined as 0.4–3 μm2, were quantified by ImageJ using the particle analyze feature with color threshold (n = 10–12 samples per group).

To quantify the efficiency of overexpression and silencing of α2δ1, a 10× objective was used to capture cell images by phase contrast microscopy. The number of neuron-like cells was determined in each sample before antibiotic selection (n = 4 samples). Cell samples were imaged again and the number of neuron-like cells was identified 24 hr after antibiotic selection. The transfection efficiency was calculated as: (number of neuron-like cells before antibiotics treatment/the number of neuron-like cells after antibiotics treatment) × 100%.

To quantify the relative fluorescence intensity of α2δ1 immunostaining, ImageJ software was used to determine the fluorescence intensity of α2δ1-positive cells using the polygon selection module (n = 30 cells per group). The same module was used to identify the background fluorescence level by selection of three regions adjacent to target cells. CTCF was calculated as: α2δ1 immunofluorescence density – (studied region × background fluorescence). Normality test was performed by Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Either Student's t test or ANOVA was applied for analysis. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Z.L., X.L., Y.J., and Z.H. designed the project, performed experimental work, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully received antibodies from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) and NeuroMab, and plasmid from Addgene. The study was supported by an NIH grant to Z.H. (R01DC013275).

Published: June 7, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes seven figures and five tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.05.006.

Supplemental Information

References

- Adams L.D., Choi L., Xian H.Q., Yang A., Sauer B., Wei L., Gottlieb D.I. Double lox targeting for neural cell transgenesis. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2003;110:220–233. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00651-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsina B., Abello G., Ulloa E., Henrique D., Pujades C., Giraldez F. FGF signaling is required for determination of otic neuroblasts in the chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 2004;267:119–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Jongkamonwiwat N., Abbas L., Eshtan S.J., Johnson S.L., Kuhn S., Milo M., Thurlow J.K., Andrews P.W., Marcotti W. Restoration of auditory evoked responses by human ES-cell-derived otic progenitors. Nature. 2012;490:278–282. doi: 10.1038/nature11415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu C., Allen N.J., Susman M.W., O'Rourke N.A., Park C.Y., Ozkan E., Chakraborty C., Mulinyawe S.B., Annis D.S., Huberman A.D. Gabapentin receptor alpha2delta-1 is a neuronal thrombospondin receptor responsible for excitatory CNS synaptogenesis. Cell. 2009;139:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feledy J.A., Beanan M.J., Sandoval J.J., Goodrich J.S., Lim J.H., Matsuo-Takasaki M., Sato S.M., Sargent T.D. Inhibitory patterning of the anterior neural plate in Xenopus by homeodomain factors Dlx3 and Msx1. Dev. Biol. 1999;212:455–464. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenz D.A., Liu W., Cvekl A., Xie Q., Wassef L., Quadro L., Niederreither K., Maconochie M., Shanske A. Retinoid signaling in inner ear development: a “Goldilocks” phenomenon. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010;152A:2947–2961. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsch B., Beisel K.W., Jones K., Farinas I., Maklad A., Lee J., Reichardt L.F. Development and evolution of inner ear sensory epithelia and their innervation. J. Neurobiol. 2002;53:143–156. doi: 10.1002/neu.10098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griggs R.B., Bardo M.T., Taylor B.K. Gabapentin alleviates affective pain after traumatic nerve injury. Neuroreport. 2015;26:522–527. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Zhang B., Luo X., Zhang L., Wang J., Bojrab D., 2nd, Jiang H. The astroglial reaction along the mouse cochlear nerve following inner ear damage. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2014;150:121–125. doi: 10.1177/0194599813512097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Liu Z., Li X., Deng X. Stimulation of synapse formation between stem cell-derived neurons and native brainstem auditory neurons. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13843. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13764-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Sinicrope F.A. Sorafenib inhibits STAT3 activation to enhance TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:742–750. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh S., Kim N., Yin H.H., Harris I.R., Dejneka N.S., Eroglu C. Human umbilical tissue-derived cells promote synapse formation and neurite outgrowth via thrombospondin family proteins. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:15649–15665. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1364-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Herault K., Oheim M., Ropert N. FM dyes enter via a store-operated calcium channel and modify calcium signaling of cultured astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:21960–21965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909109106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhou H., Fu X., Xiao R. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into keratinocyte progenitors in vitro: an attempt with promise of clinical use. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2016;52:885–893. doi: 10.1007/s11626-016-0024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillevali K., Haugas M., Matilainen T., Pussinen C., Karis A., Salminen M. Gata3 is required for early morphogenesis and Fgf10 expression during otic development. Mech. Dev. 2006;123:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., McDonough S.I., Lipscombe D. Alternative splicing in the voltage-sensing region of N-Type CaV2.2 channels modulates channel kinetics. J. Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2820–2830. doi: 10.1152/jn.00048.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F.R., Thorpe R., Gordon-Salant S., Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2011;66:582–590. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Davis R.L. Calretinin and calbindin distribution patterns specify subpopulations of type I and type II spiral ganglion neurons in postnatal murine cochlea. J. Comp. Neurol. 2014;522:2299–2318. doi: 10.1002/cne.23535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Hu Z. Aligned contiguous microfiber platform enhances neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:6087. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24522-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Kipnis J. Thrombospondin 1–a key astrocyte-derived neurogenic factor. FASEB J. 2010;24:1925–1934. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C.C., Appler J.M., Houseman E.A., Goodrich L.V. Developmental profiling of spiral ganglion neurons reveals insights into auditory circuit assembly. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:10903–10918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2358-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X.J., Deng M., Xie X., Huang L., Wang H., Jiang L., Liang G., Hu F., Tieu R., Chen R. GATA3 controls the specification of prosensory domain and neuronal survival in the mouse cochlea. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:3609–3623. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M. Role of calpains in the injury-induced dysfunction and degeneration of the mammalian axon. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013;60:61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M., Nakagawa T., Kojima K., Sakamoto T., Fujiyama F., Ito J. Potential of embryonic stem cell-derived neurons for synapse formation with auditory hair cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86:3075–3085. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka A.J., Morrissey Z.D., Zhang C., Homma K., Belmadani A., Miller C.A., Chadly D.M., Kobayashi S., Edelbrock A.N., Tanaka-Matakatsu M. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells toward placode-derived spiral ganglion-like sensory neurons. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017;6:923–936. doi: 10.1002/sctm.16-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z.L., Davis R.L. Endogenous firing patterns of murine spiral ganglion neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1294–1305. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayagam B.A., Muniak M.A., Ryugo D.K. The spiral ganglion: connecting the peripheral and central auditory systems. Hear. Res. 2011;278:2–20. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer P.L., Gerster T., Lun K., Brand M., Busslinger M. Characterization of three novel members of the zebrafish Pax2/5/8 family: dependency of Pax5 and Pax8 expression on the Pax2.1 (noi) function. Development. 1998;125:3063–3074. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J.H., O'Shea K.S., Wys N.L., Velkey J.M., Prieskorn D.M., Wesolowski K., Miller J.M., Altschuler R.A. Glutamatergic neuronal differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells after transient expression of neurogenin 1 and treatment with BDNF and GDNF: in vitro and in vivo studies. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:12622–12631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0563-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard A., Hayes S.H., Chen G.D., Ralli M., Salvi R. Review of salicylate-induced hearing loss, neurotoxicity, tinnitus and neuropathophysiology. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2014;34:79–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic K., Rio C., Xia A., Sugawara M., Adams J.C., Liberman M.C., Corfas G. Survival of adult spiral ganglion neurons requires erbB receptor signaling in the inner ear. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8651–8661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0733-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Jiang H., Hu Z. Concentration-dependent effect of nerve growth factor on cell fate determination of neural progenitors. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1723–1731. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.