Abstract

Mucus is a major component of the intestinal barrier involved both in the protection of the host and the fitness of commensals of the gut. Streptococcus thermophilus is consumed world-wide in fermented dairy products and is also recognized as a probiotic, as its consumption is associated with improved lactose digestion. We determined the overall effect of S. thermophilus on the mucus by evaluating its ability to adhere, degrade, modify, or induce the production of mucus and/or mucins. Adhesion was analyzed in vitro using two types of mucins (from pig or human biopsies) and mucus-producing intestinal HT29-MTX cells. The induction of mucus was characterized in two different rodent models, in which S. thermophilus is the unique bacterial species in the digestive tract or transited as a sub-dominant bacterium through a complex microbiota. S. thermophilus LMD-9 and LMG18311 strains did not grow in sugars used to form mucins as the sole carbon source and displayed weak binding to mucus/mucins relative to the highly adhesive TIL448 Lactococcus lactis. The presence of S. thermophilus as the unique bacteria in the digestive tract of gnotobiotic rats led to accumulation of lactate and increased the number of Alcian-Blue positive goblet cells and the amount of the mucus-inducer KLF4 transcription factor. Lactate significantly increased KLF4 protein levels in HT29-MTX cells. Introduction of S. thermophilus via transit as a sub-dominant bacterium (103 CFU/g feces) in a complex endogenous microbiota resulted in a slight increase in lactate levels in the digestive tract, no induction of overall mucus production, and moderate induction of sulfated mucin production. We thus show that although S. thermophilus is a poor mucus-adhesive bacterium, it can promote mucus pathway at least in part by producing lactate in the digestive tract.

Keywords: mucus, mucin, microbiota, gut, lactic acid bacteria, lactate, gnotobiotic rodent

Introduction

Streptococcus thermophilus is a lactic acid bacterium traditionally used by the food industry because of its ability to ferment and acidify milk. It is one of the two bacteria used in yogurt, defined as “the coagulated milk product obtained by lactic acid fermentation through the action of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (L. bulgaricus) and S. thermophilus from milk and milk products" (FAO/WHO, 2002). S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus are alive and abundant (at least 107CFU/g) in the final product, with S. thermophilus being more abundant (Herve-Jimenez et al., 2009; Ben-Yahia et al., 2012). S. thermophilus is used as a dairy starter because it efficiently converts lactose into lactic acid, which rapidly reduces the pH and coagulates the caseins of milk. This bacterium also confers texture and taste properties to yogurt, such as viscosity, acidity, and water holding capacity (Rul, 2017). Aside from its technological advantages, S. thermophilus can provide health benefits to consumers. The presence of living bacteria in yogurt is associated with a better capacity to digest lactose for individuals with lactose intolerance. This is due to their β-galactosidase activity, which compensates the lactose-degrading deficiency of host intestinal cells. The health benefit conferred by the consumption of yogurt is sufficiently supported by scientific evidence that the claimed effect of aiding lactose digestion associated with live yogurt cultures has been acknowledged by the European Food Safety Authority [Efsa Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA), 2010]. To date, the beneficial physiological effect provided by the two yogurt bacteria is the unique health claim related to the presence of living cultures. It may be worthwhile to explore other beneficial properties of S. thermophilus that could enlarge the health benefits linked to its consumption.

By degrading lactose, S. thermophilus produces lactate that can shape and reinforce endogenous bacterial communities of the intestinal microbiota in the digestive tract (Veiga et al., 2010). Lactate is a powerful antimicrobial factor that inhibits the growth of pathogens and participates in the trophic chain between microbial communities, because it favors the growth of bacteria that consume lactate and subsequently generate secondary short chain fatty acids, such as propionate and butyrate (Louis and Flint, 2017). Lactate is thus an intermediate metabolite used as a substrate by commensals. It may also be involved in the physiology of epithelial cells, although it is yet to be determined whether lactate, in the intestine is preferentially consumed by bacteria or host cells. The role of lactate as a mediator in the dialog between S. thermophilus and the host has been highlighted in an experimental rat model mono-colonized with the strain LMD-9 (Rul et al., 2011). The presence of LMD-9 alone in the digestive tract of these gnotobiotic rats results in the accumulation of high levels of lactate (from >10 to 50 mM) in the lumen, concomitantly with the increase of certain intestinal proteins involved in cell-cycle arrest. The preferential arrest of proliferation and differentiation of eukaryote cells by lactate has also been proposed (Hsiao et al., 2009). Thus, the glycolytic activity of S. thermophilus in vivo sustains health, through the degradation of lactose and the subsequent production of lactate.

Mucus is a major component of the intestinal barrier and is involved in the protection, defense, and homoeostasis between commensals and host (Sicard et al., 2017). A decrease in mucus thickness leads to inflammatory diseases and, hence, a bacterium which promotes mucus formation could reinforce defense (Van Herreweghen et al., 2017). The formation of mucus in the gut is a dynamic process ensured by goblet cells and driven by transcription factors, such as KLF4 (Zheng et al., 2009). The continuous production of mucus, and its thickness, composition, and penetrability are shaped by the intestinal microbiota (Wrzosek et al., 2013; Jakobsson et al., 2015; Johansson et al., 2015). For example, mucus adhesins expressed at the cell surface of Lactobacillus reuteri strains may exert immune regulatory effects in the gut (Bene et al., 2017; de Vos, 2017). Better adhesion of probiotics and bacteria in transition should improve persistence and favor an intimate dialog with epithelial cells. Thus, adhesion to mucus is a factor often ascribed to probiotic characteristics in the gut (FAO/WHO, 2002), but this assumption requires further studies for validation and generalization.

Although adhesion is not a necessary criterion to estimate a potential benefit, it is still an important property, together with mucin/mucin sugar degradation, for understanding the overall effect of a strain in the digestive environment. Little is known concerning the overall mucophilic potential of S. thermophilus, except for one recent study showing that sortase-dependent proteins are involved in its adhesion profile (Kebouchi et al., 2016). The aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of S. thermophilus to adhere, degrade, modify, or induce the production of mucus and/or mucins.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Culture Conditions

The strains S. thermophilus LMD-9 (ATCC BAA-491, United States) and LMG18311 (BCCM collection, Belgium) were used. Stock cultures of S. thermophilus LMD-9 and LMG18311 were prepared in reconstituted 10% (w/v) Nilac skim milk (NIZO, Ede, Netherlands).

Two Lactococcus lactis bacterial strains were used in this study: L. lactis subsp. lactis TIL448 (NCDO2110), isolated from peas, and TIL1230, a derivative of TIL448 obtained after curing plasmids by acridine orange treatment, devoid of pili and mucus-binding protein (Meyrand et al., 2013). Bacterial stock cultures were maintained at −80°C in M17 broth (Oxoid), containing 0.5% (w/v) glucose and 20% (v/v) glycerol. Bacteria were first sub-cultured overnight at 37°C (S. thermophilus) or 30°C (L. lactis) in M17-lactose [1% (w/v)] (S. thermophilus) or glucose [0.5% (w/v)] (L. lactis) medium (M17Glc). This preculture was then used to inoculate M17Glc at 37 or 30°C. Bacteria were harvested during the exponential growth phase [optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 3] by centrifugation (2000 × g, 20 min, room temperature) and the pellet was washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

LMD-9 ster_0152::kana strain (LMD-9Kana) was constructed as follows. The kanamycin (kana) cassette of the plasmid pKa (Debarbouille et al., 1990) was PCR amplified using Phusionhigh fidelity DNA polymerase (Fermentas) with AphA3F (5′CCAGCGAACCATTTGAG3′) and AphA3R (5′GTTGCGGATGTACTTCAG3′) primers. The DNA fragments flanking the ster_0152 gene were PCR amplified using Phusion DNA polymerase, LMD-9 DNA as template, and A1 (5′CTTACCTATCACCTCAAATGGTTCGCTGGGTTT ATCTTAAAATGATTTATCGTC3′) and A3 (5′GGACAGC CGTAAACTATC3′) primers for the upstream fragment, and A2 (5′AGGGGTCCCGAGCGCCTACGAGGAATTTGTATCGA T3GGGACAGAACATTGTACC3′) and A4 (5′CATCCATTAA GACGCCCC3′) primers for the downstream fragment. The 3′ end of the generated upstream fragment contained a sequence complementary to the 5′ end of the kana cassette, whereas the 5′ end of the generated downstream fragment contained a sequence complementary to the 3′ end of the cassette. This allowed joining of these three fragments after TaqPhusion PCR using primers A3 and A4. After purification with a QIAquick PCR purification kit, 500 ng of the resulting fragment was further used to transform competent natural LMD-9 cells as described by Gardan et al. (2009). LMD-9Kanaclones were selected on M17Lac plates with kanamycin (1 mg/ml) and then verified by two PCRs using oligonucleotides A1 × A3 and A2 × A4. Finally, sequencing of the flanking regions was performed to ensure that no unwanted mutations were introduced. The two strains, LMD-9Kana and native LMD-9, grew similarly in M17 lactose-rich (1%, w/v) medium and milk (data not shown).

Degradation of Mucin Sugars by S. thermophilus

The ability of S. thermophilus LMD-9 and LMG18311 to degrade mucin sugars was evaluated by following their growth in microtiter plates with Yeast Extract medium (YE, Biokar diagnostics A1202 HA) containing 10 g/L of one of the carbon sources to be tested (galactose, mannose, fucose, N-acetyl glucosamine, N-acetyl galactosamine, or lactose) at 42°C. The growth rates are expressed as μMaxmeans ± SD (n = 7).

HT29-MTX Culture

The mucus-secreting cell line HT29-MTX was obtained from Thecla Lesuffleur (INSERM Paris, France). Cells were routinely grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) containing phenol red and 4.5 g/L glucose (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium), supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% (v/v) L-glutamine 200 mM, and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin mixture (10000 U/mL and 10000 μg/mL, respectively) (all from Lonza). Cells were seeded at a concentration of 2.5 × 104 cells/cm2 in six-well tissue-culture plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific - Nunc A/S, Waltham, MA, United States). Two days before the experiments, antibiotics were no longer added to the cell culture medium. Experiments were carried out 20–22 days post seeding to ensure full differentiation of cells. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 10% CO2 and the culture medium was changed daily.

Bacterial Adhesion to HT29-MTX Cells

Adhesion experiments of S. thermophilus LMD-9 to the HT29-MTX cell line were performed according to the method described previously by Turpin et al. (2012), with some modifications. TIL448 and TIL1230 were used as high-adhesive and low-adhesive controls, respectively (Le et al., 2013). Bacterial cells from precultures were used to inoculate cell-culture medium with a reduced FBS concentration [2% (v/v)] at a starting OD600 nm = 0.05. After an adaptation phase, bacteria were washed, suspended in fresh culture medium with 2% FBS, and diluted to obtain a bacterial-cell concentration of 3–4 × 107CFU/mL. HT29-MTX cells were gently washed twice with PBS, pH 7.5 (Lonza) and 2 mL bacterial suspensions added to each well, resulting in a bacterial cell to epithelial cell ratio (MOI) of 10:1. The bacterial and epithelial cells were co-incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 10% CO2. After incubation, HT29-MTX cells were washed twice with PBS to remove unbound bacteria, scraped with 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), filtered five times through a 21-gauge needle, and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The number of viable bacterial cells was determined in the cell pellet (adherent bacterial cells) and bacterial suspension after incubation in empty wells (control input) by the plating method. Results are expressed as the percentage of adherent bacterial cells relative to the number of bacteria added (control input). At least three independent experiments were performed and at least three serial dilutions in duplicate were carried out for each well.

Co-incubation of HT29-MTX Cells With Lactate

Cells were cultivated for 7 days and incubated with 0, 20, or 50 mM lactate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) for 17 h. The pH was verified and adjusted to that of normal culture medium for culture medium containing lactate. Each condition was tested in triplicate and experiments were repeated three times. Cells were scraped off and immediately used for protein extraction.

Binding to Mucins

A solution of type III mucin from porcine stomach (PGM) (cat. no. M1778, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) [10 mg/mL] was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.5 and used to coat 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific - Nunc A/S). Adhesion of S. thermophilus LMD-9 and LMG18311 to PGM-coated polystyrene plates was tested using the technique described for the L. lactis IBB477 strain (Radziwill-Bienkowska et al., 2016). TIL448 and TIL1230 were used as high-adhesive and low-adhesive controls, respectively (Le et al., 2013). Briefly, bacterial suspensions (OD600 nm = 1) were incubated in coated plates for 3 h at room temperature, unbound bacteria washed away, and adherent bacteria stained with crystal violet before solubilization in acetic acid. Adhesion is expressed as the optical density (OD583 nm) of stained cells. Bacterial adhesion was determined in three independent experiments and results are presented as the means ± SD. The average value of at least six measurements was calculated after rejecting extreme results.

Adhesion to Purified Human Mucins

Approval and Accordance for Human Samples

Colorectal tissues from healthy individuals arised from patients with diverticulosis. The use of human tissues for this study was approved by the local hospital ethics committee and French Ministry of Higher Education and Research (DC-2008-242). All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The procedure was adapted from that of Da Silva et al. (2015) to evaluate the binding of S. thermophilus LMD-9 to human colonic mucin. TIL448 and TIL1230 were used as high-adhesive and low-adhesive controls, respectively (Le et al., 2013). In brief, mucin was scraped and purified from human biopsies and spotted (10 μg) on dry nitrocellulose membranes. PGM was used as control. Bacteria (109 CFU/mL in phosphate-buffered saline) were stained with DAPI for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Labeled bacteria were added to the membrane in blocking buffer. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, the fluorescence of adherent bacteria was detected by a ChemiGenius 2 imaging system (Syngene).

Animals and Experimental Design

Approval and Accordance

All procedures for gnotobiotic rats were carried out according to European guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals with permission from the French Veterinary Services dedicated to M. T (78-123) and as previously described by Rul et al. (2011).

All mice experiments were approved by the local Animal Ethics Review Committee of the Faculty/Paris 7 University with permission dedicated to the unit of EOD [EU0543 - Fac Méd X. Bichat – Animal. Centr. - APAFiS - Autor. APAFiS #6424].

Ino-LMD9: All mono-colonized rats were previously described by Rul et al. (2011). Briefly, 2-month-old germ free (GF) rats (male, Fisher 344) were inoculated by a single gavage with 1 mL 5 × 108 CFU/mL S. thermophilus LMD-9 (Ino-LMD9, n = 6). As a control, GF rats (n = 5) were also inoculated with 1 mL sterile Nilac milk (without bacteria). All gnotobiotic rats for which the drinking water was supplemented with lactose (4.5%wt/vol) are designated as +lac (GF+lac, n = 6 and Ino-LMD9+lac, n = 6). All rats were euthanized 30 days after gavage to recover biological samples.

Ino-LMD9Kana mice: Male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. After receipt, mice were acclimated for 1 week and then randomized into control (n = 5) and treated (n = 5) groups. Mice were housed in a conventional animal facility under a 12:12-h light/dark cycle. Food and tap water were provided ad libitum. Five individuals per cage were housed in the same room. At the age of 4 weeks, mice were inoculated by oral gavage (108 CFU/mL in 150 μL/mouse), five times a week (from Monday to Friday), at 10 a.m. for 3 weeks, either with S. thermophilus LMD9Kana (Ino-LMD9Kana, n = 5) or Nilac skim milk (Ctrl, without bacteria) (n = 5). Stool samples were collected two times a week at 4 p.m. All mice were euthanized at the age of 7 weeks by cervical dislocation.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry Assays

Flushed colons of rats and mice were opened longitudinally and cut into 2-cm sections. The samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (4 h, room temperature), dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin, according to standard histological protocols. Four-micrometer thick sections of rat distal colon (proximal, median, and distal for mice) were mounted on SuperFrost® Plus slides (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, United States). Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized and stained with Hematoxylin and Alcian blue (AB) solution pH 2.5 to count the number of total and goblet cells per crypt, respectively. MUC2 immunostaining was performed for rats using the EnVision + System-HRP (Dako-Cytomation, Trappes, France) and anti-MUC2 antibody (1:5000; sc-15334, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany), as previously described (Tomas et al., 2013). Only U-shaped longitudinally cut crypts with open lumina were counted. The reported results are the means obtained by analysis of at least 10 crypts per site using Nanozoomer Digital Pathology view software (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan).

Western Blot Analysis

Colonic epithelial cells were isolated from the whole colon of rats and mice according to the method of Cherbuy et al. (1995). The cell pellet from whole colon or HT29-MTX cell cultures was immediately used for protein extraction (Cherbuy et al., 2010) and Lowry’s procedure was used for protein assays. Western blot analysis was performed using 12% SDS-PAGE and anti-KLF4 (1:500; IMG-6081A, Imgenex, San Diego, CA, United States), with an appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch laboratories, West Grove, PA, United States). For each western blot, protein loads were determined using anti-cullin1 (1:200; sc-17775, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-GAPDH (1:1000; 905-734-100, Stressgen) antibodies. Signals detected on autoradiographic films were quantified by scanning densitometry using a Biovision 1000 and Bio-1D software (Vilber Lourmat, France).

Total RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from colonic epithelial cells isolated from rat tissues by the guanidinium thiocyanate method (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). RNA concentration and purity were determined by absorbance using a Nanodrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Illkirch, France) and the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) determined using an RNA 6000 Nano LabChip® kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) and an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer at the ICE platform (INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France). All RNA had a RIN between 8 and 10, indicating that the RNA of all samples was of high quality. Reverse transcription was performed with 7 μg RNA of each sample using the High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies SAS, Saint Aubin, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. No inhibition was detected for any sample using the TaqMan® Exogenous Internal Positive Control (Applied Biosystems). The cDNA products were analyzed in triplicate by RT-qPCR with an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System and 7000 system software, version 1.2.3 (Applied Biosystems). Muc2 mRNA was analyzed using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Rn01498197_m1, Applied Biosystems. 18S rRNA (Hs99999901_s1) was used as a reference. Results obtained were normalized to the value for 18S rRNA and compared with the mean target gene expression in GF rats as the calibrator sample. The following formula was used: fold change = 2−ΔΔCt, where ΔΔCt threshold cycle (Ct) equals (target Ct – reference Ct) of the sample minus (target Ct – reference Ct) of the calibrator.

Metabolite Analysis

Acetate, propionate, butyrate, valerate, isobutyrate, and isovalerate concentrations were determined in cecum contents of mice after water extraction of acidified samples by gas liquid chromatography (Nelson 1020, Perkin-Elmer, St Quentin en Yvelines, France), as previously described (Lan et al., 2008). Lactate measurements were performed from the cecum content of rats and mice, as previously described (Ben-Yahia et al., 2012). The metabolite concentrations are expressed in mM.

Analysis of Mucin O-glycosylation in Mice

Distal colonic mucosa was scraped and the mucins solubilized and purified by isopycnic density-gradient centrifugation (Beckman Coulter LE80K ultracentrifuge; 70.1 Ti rotor, 308, 500 × g at 15°C for 72 h) (Rossez et al., 2012). The mucin-containing fractions were pooled, dialyzed into water, lyophilized, and further submitted to β-elimination under reductive conditions [0.1 M NaOH, 1 M KBH4 for 24 h at 45°C]. Permethylation of the mixture of oligosaccharide alditols was carried out using the sodium hydroxide procedure. After derivation, the reaction products were dissolved in 200 μL methanol and further purified on a C18 Sep-Pa cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA, United States). Permethylated oligosaccharides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in positive ion reflective mode as [M+Na]+. The relative percent of each oligosaccharide was calculated based on the integration of peaks of MS spectra.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, United States). For in vitro binding experiments, data are reported as the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison test, was performed to compare data groups. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from the high-adhesive L. lactis strain or from low-adhesive L. lactis stain (∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗∗p < 0.01). For animal experiments, data are reported as the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) and t-test or ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s Student range test, were performed to compare the data between different batches of animals (∗p < 0.05).

Results

In Vitro Mucus-Adhesion and Degradation of Mucin Sugars by S. thermophilus

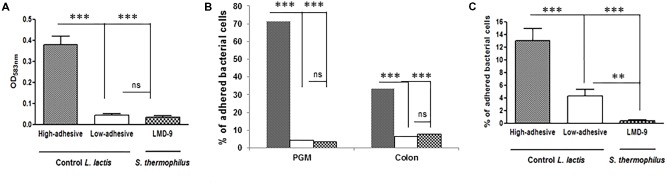

We established various models to assess the ability of S. thermophilus to bind mucus and mucins. We used two types of purified mucins: commercial pig gastric mucin (PGM) and colonic mucin isolated from human biopsies. The LMD-9 strain was co-incubated with PGM coated on polystyrene microplates (Figure 1A) or human mucin vs. PGM spotted on nitrocellulose membranes (Figure 1B). The TIL448 L. lactis strain, known to be highly adhesive (Le et al., 2013; Meyrand et al., 2013), was used as a positive control and indeed bound to PGM. In contrast, S. thermophilus LMD-9 bound as poorly as our negative L. lactis control, TIL1230 (Figures 1A,B). The adhesive profile of L. lactis TIL448 was also high for human samples, whereas that of S. thermophilus LMD-9 was low, identical to that of TIL1230 (Figure 1B). We also used intestinal HT29-MTX cells to mimic the continuous and dynamic production of mucus (Figure 1C). Binding of the S. thermophilus LMD-9 strain to HT29-MTX cells was also low. Thus, S. thermophilus LMD-9 displayed poor binding to mucus and mucins relative to that of the high-adhesive L. lactis TIL448 strain, regardless of the model tested (Figure 1). The low ability of S. thermophilus to bind mucin was confirmed with the other strain tested, LMG18311 (data not shown). We then evaluated the ability of S. thermophilus to use the sugars forming the mucin glycans as their sole carbon source. The growth of S. thermophilus was characterized in microplates with culture medium supplemented with galactose, mannose, fucose, N-acetyl glucosamine, N-acetyl galactosamine, or lactose, which is the preferred substrate of S. thermophilus. The maximal growth rate (μmax) of LMD-9 was 0.27 ± 0.08 h−1 in the presence of lactose, whereas this strain did not grow in any of the sugars forming mucins as their sole carbon source. We obtained similar results with the LMG18311 strain, with a μmax reaching 0.30 ± 0.05 h−1 in the presence of lactose and no growth in the presence of the mucin sugars. Overall, these data show that two strains of S. thermophilus (LMD-9 and LMG18311) adhere poorly to mucus and mucins in vitro, and are unable to grow in vitro with mucin sugars as the sole carbon source.

FIGURE 1.

Invitro adhesion of S. thermophilus LMD-9( ) vs. the high-adhesive L. lactisTIL448 (

) vs. the high-adhesive L. lactisTIL448 ( ) and low-adhesive L. lactisTIL1230 (

) and low-adhesive L. lactisTIL1230 ( ). (A) PGM-coated polystyrene microplates: adhesion is expressed as optical density (OD583

nm) of stained cells. (B) Human colonic mucin spotted on nitrocellulose membranes: adhesion is expressed as the percentage of adherent bacterial cells relative to the number of bacteria added. (C) Mucus-secreting HT29-MTX cells: adhesion is expressed as the percentage of adherent bacterial cells relative to the number of bacteria added. The means ± SEM from three independent experiments are shown (∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ns, not significant).

). (A) PGM-coated polystyrene microplates: adhesion is expressed as optical density (OD583

nm) of stained cells. (B) Human colonic mucin spotted on nitrocellulose membranes: adhesion is expressed as the percentage of adherent bacterial cells relative to the number of bacteria added. (C) Mucus-secreting HT29-MTX cells: adhesion is expressed as the percentage of adherent bacterial cells relative to the number of bacteria added. The means ± SEM from three independent experiments are shown (∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ns, not significant).

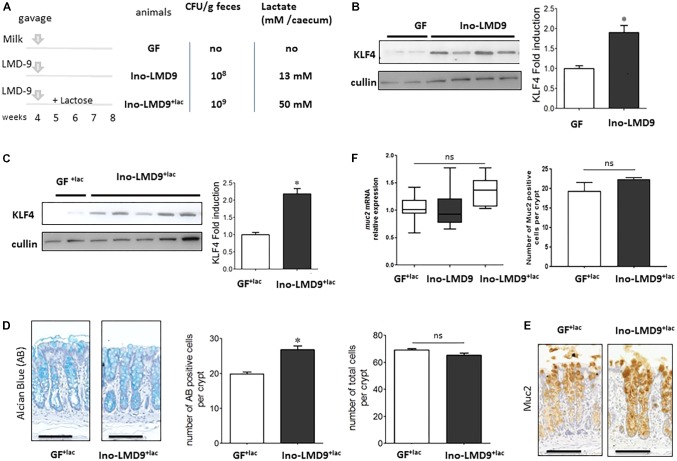

Mucus-Induction by S. thermophilus in a Simplified in Vivo Gnotobiotic Model

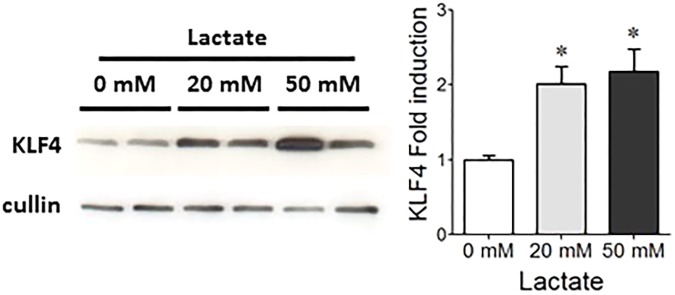

We tested the ability of S. thermophilus to modulate the mucus pathway of intestinal epithelial cells by studying mono-colonized adult rats, harboring LMD-9 as the sole bacterium in their digestive tract. Ino-LMD9 rats, which we previously described (Rul et al., 2011), were colonized by up to 108CFU/g feces and accumulated 13 mM of lactate in the cecum (Figure 2A). When lactose (4.5% w/v) was added in drinking water (Thomas et al., 2011), the level of colonization was 109 CFU/g feces and lactate accumulated up to 50 mM in mono-colonized Ino-LMD9+lacrats (Figure 2A). The presence of S. thermophilus in the digestive tract induced the amount of KLF4 protein in epithelial cells of the colon in two groups without and with lactose (Figures 2B,C). The level of induction is 1.9 (±0.6) in Ino-LMD9 and 2.1(±0.46) in Ino-LMD9+lac in comparison with their respective germ free counterparts (p < 0.05) and the two groups of mono-associated rats (with and without lactose) displayed similar amount of KLF4 protein. There was also a comparable induction of KLF4 in mono-colonized rats carrying the LMG18311 strain (Supplemental Figure 1). Goblet cells stained by Alcian Blue were more abundant in Ino-LMD9+lac than with GF+lac rats (Figure 2D), whereas the number of total cells per crypt was the same. The production of Muc2 protein, the main mucin secreted in the colon, seems to be higher in the Ino-LMD9+lac rats than in GF (Figure 2E), but the mRNA level and the number of Muc2 positive cells were unchanged after colonization of the colon by S. thermophilus LMD9+lac (Figure 2F). Overall, these data show that two strains of S. thermophilus, LMD9 and LMG18311, induced KLF4 protein in mono-colonized rats in the presence or not of a continuous lactose supply, concomitantly with the accumulation of high amount of lactate (from 13 to 50 mM) in their digestive tract. We then evaluated the effect of lactate (20 and 50 mM) on KLF4 protein production by the mucus-producing HT29-MTX cell line (Figure 3). Lactate significantly increased the amount of KLF4 and the level of induction was equivalent regardless of the concentration tested (20 or 50 mM in vitro). Overall, S. thermophilus can induce KLF4 protein and the number of Alcian-Blue positive goblet cells when it is the only bacterium in the digestive tract of rats. Based on our observations in HT29-MTX cell line, we can suppose that lactate may be involved in the induction of KLF4.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of the colonic epithelial response in S. thermophilusLMD-9 mono-colonized rats. Germfree (GF) rats were inoculated with sterile milk (GF, n = 5) or with 5 × 108 CFU of a culture of S. thermophilus LMD-9 (Ino-LMD9, n = 6) and euthanized 30 days after inoculation. Similar groups GF+lac (n = 6) and Ino-LMD9+lac (n = 6) were given tap water containing 4.5% (w/v) lactose (A) Experimental design: establishment of S. thermophilus LMD-9 (with or without lactose) in the gastrointestinal tract was monitored by enumeration of the bacterial counts in the feces. The lactate concentration was measured in the cecum. (B) Representative western blot and densitometric analyses of KLF4 protein in GF and Ino-LMD9 samples. (C) Representative western blot and densitometric analyses of KLF4 protein in GF+lac and Ino-LMD9+lac samples. (D) Representative images, counts of goblet cells stained with Alcian Blue (indicated as AB) and counts of total number of cells per crypt stained with Hematoxylin from in GF+lac and Ino-LMD9+lac samples; scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Representative images, Muc2 immunostaining in GF+lac and Ino-LMD9+lac rats; scale bar: 50 μm. (F) muc2 mRNA expression level in GF+lac, Ino-LMD9 and Ino-LMD9+lac rats, and counts of the number of muc2 positive cells per crypt GF+lac and Ino-LMD9+lac rats. The asterisk indicates a statistical difference relative to GF rats (p < 0.05); ns: not significant.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of lactate on KLF4 protein levels in HT29-MTX cells. Representative western blot and densitometric analyses of KLF4 protein in HT29-MTX cells incubated with 0, 20, or 50 mM lactate. The means ± SEM from three independent experiments are shown (∗p < 0.05).

Mucus-Related Properties of Streptococcus thermophilus in Mice Harboring a Complex Microbiota

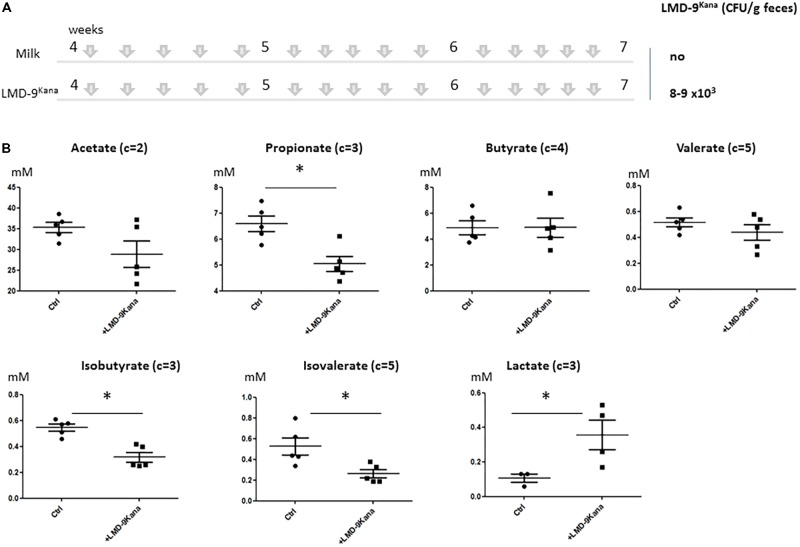

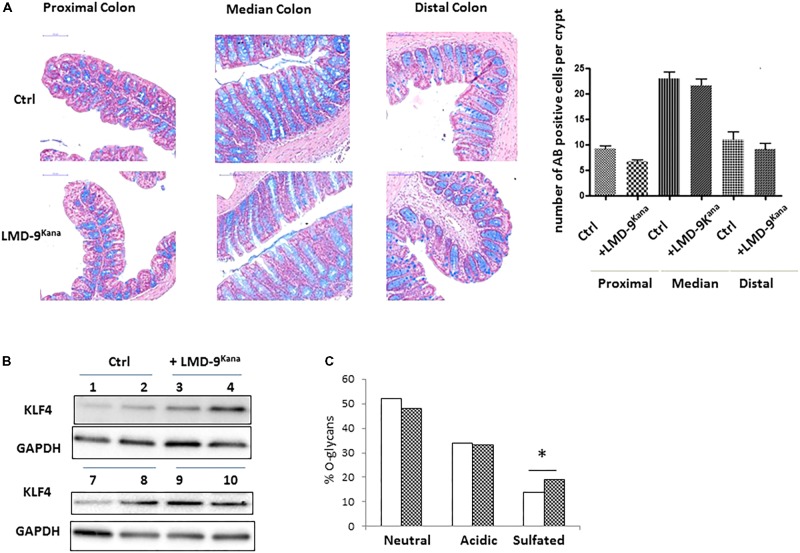

The use of mono-colonized rodents allowed us to assess several mucus-related functions in an over-simplified digestive system. We next characterized the effect of S. thermophilus in mice harboring a complex microbiota by constructing an LMD-9 mutant strain resistant to kanamycin (LMD-9Kana), enabling the evaluation of the colonization level of S. thermophilus in a complex bacterial community. The adult mice received either milk fermented with LMD-9Kana or only milk (Ctrl) five times per week for 3 weeks (Figure 4A). We detected 8–9 103 CFU/g feces of LMD-9Kana (Figure 4A), showing that live bacteria transited through the digestive tract, whereas no LMD-9Kana was present in the Ctrl group, as expected. We assessed the fermentative profile of the microbial community by measuring the levels of short chain fatty acids and lactate in the cecum (Figure 4B). Mice receiving LMD-9Kana had significant levels of lactate (up to 0.5 mM) in the cecum and lower levels of propionate, isobutyrate, and isovalerate than the Ctrl group (p < 0.05). Thus, the transiting of S. thermophilus as sub-dominant bacteria, may orientate the activity of the resident and abundant microbiota. The number of goblet cells and KLF4 protein levels in the colon were not different in the mice that received LMD-9Kana than in Ctrl mice (Figures 5A,B). Probiotic or commensal bacteria are known to modulate the composition and physical properties of mucus through changes in mucin O-glycans (Wrzosek et al., 2013; Da Silva et al., 2014). We thus profiled the O-glycosylation pattern of colonic mucins. The number of sulfated mucins was significantly higher in mice receiving LMD-9Kana than in Ctrl mice (Figure 5C). Thus, transit of S. thermophilus as a sub-dominant bacterium through the microbiota resulted in modification of some bacterial metabolite levels, with lactate levels, no induction of the mucus pathway, and a moderate induction of sulfated mucin.

FIGURE 4.

Impact of S. thermophilus LMD-9 on the fermentative profile of the gut microbiota in conventional mice. C57BL/6J mice were inoculated by oral gavage (150 μL of 108 CFU/mL/mouse), five times a week, for 3 weeks, with either S. thermophilus LMD9Kana (Ino-LMD9Kana, n = 5) or sterile milk (Ctrl, n = 5). (A) Experimental design; establishment of S. thermophilusLMD-9 in the gastrointestinal tract was monitored by enumeration of the bacterial counts in the feces. (B) Cecal composition of acetate, propionate, butyrate, valerate, isobutyrate, isovalerate, and lactate. The number of carbon parts per substrate is indicated for each metabolite. The asterisk indicates a statistical difference compared to Ctrl mice (p < 0.05).

FIGURE 5.

Characterization of the colonic epithelial response to S. thermophilus LMD-9 in conventional mice. (A) Representative pictures and counts of goblet cells stained with Alcian Blue (indicated as AB) in proximal, median, and distal colon of Ctrl (n = 5) and Ino-LMD9Kana (n = 5) samples; scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Representative western blot of KLF4 protein (involved in the mucus pathway) in Ctrl and Ino-LMD9Kana samples. (C) Proportion of neutral, acidic, and sulfated O-glycans in Ctrl ( , n = 5) and Ino-LMD9Kana (

, n = 5) and Ino-LMD9Kana ( , n = 5) samples. The asterisk indicates a statistical difference relative to Ctrl mice (p < 0.05).

, n = 5) samples. The asterisk indicates a statistical difference relative to Ctrl mice (p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the overall interactions between the food-borne bacterium S. thermophilus and mucus, using a battery of tests on in vitro and in vivo models. Two strains of S. thermophilus, LMD-9 and LMG18311, poorly adhered to mucus and mucins (Figure 1) and were unable to degrade various sugars used in mucin synthesis. S. thermophilus is thus a poor adhesive bacterium relative to other well-described mucus-adhesive lactic-acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus plantarum (Mackenzie et al., 2010; Turpin et al., 2012). Adhesion is clearly not the most determinant trait of S. thermophilus.

We have administrated S. thermophilus in recipient germ free rats and in conventional mice to characterize its effect on mucus pathway in two complementary animal models. The rats received 1ml of pure S. thermophilus culture (5∗108 CFU/ml), equivalent to the amount of S. thermophilus in ≈50 g of yogurt. In mice, we have administrated 5 times per week for 3 weeks 0.15 ml of pure S. thermophilus culture of 108 CFU/ml, equivalent to ≈1.5 g of yogurt per gavage.

The number of Alcian-Blue positive goblet cells and the level of KLF4 protein were induced in the simplified Ino-LMD9 model, in which S. thermophilus is the only bacterial species in the digestive tract (Figure 2). Mucus reinforcement is one of the mechanisms responsible for the beneficial effects of several lactic-acid bacteria. For example, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG up-regulates mucin gene expression and mucus production in intestinal epithelial cell lines through two actors: p40-derived soluble protein of the bacteria and the EGF receptor of host cells (Mattar et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2014). Adhesion to mucus has also, often been proposed to favor colonization and thus exchanges between bacteria and host. But, it has been recently shown that a key factor involved in in vitro adhesion of the Lactococcus lactis IBB477 strain did not confer a selective advantage in the intestinal tract of conventional mice (Radziwill-Bienkowska et al., 2017). The ability of lactic-acid bacteria to colonize the gut in animal models harboring a simplified microbiota is not determined by their ability to bind mucus (Turpin et al., 2013). The assumption that high adhesion confers a selective advantage in the gut and provides health benefits is thus not implicit. The transit time and metabolic activity in the gut result from multiple complex parameters, including resistance to bile salts and acidity, endogenous immune defense, microbial competitive advantage, and the availability of energy sources. The activity and metabolism of commensals that are highly specialized in the consumption of mucins or complex polysaccharides are associated with the amount of fiber in the diet (Martens et al., 2011). Genomic analysis suggests that LMD-9 lacks polysaccharide-degrading loci. We have shown that lactose boosts the metabolic activity and colonization of S. thermophilus in a simplified model, Ino-LMD9 (Thomas et al., 2011; Ben-Yahia et al., 2012), which correlated with its well-known efficient lactose permease and high β-galactosidase activities (Hols et al., 2005). Thus, the amount of mono and di-saccharides in the diet should determine the activity of S. thermophilus in the gut, especially in the upper part of the gut, in which high levels of free simple sugars are present.

Our in vitro co-incubation experiments (Figure 3) suggest that lactate produced by S. thermophilus in gnotobiotic model may sustain at least in part the stimulation of KLF4, involved in differentiation of secretive cells. This is consistent with the stimulation of cell-cycle arrest proteins and the anti-proliferative effect described for lactate in vivo and in vitro (Rul et al., 2011; Matsuki et al., 2013). However, we have previously reported that lactate accumulation produced by a mixture of three lactobacilli has no effect on mucus production in gnotobiotic rodents (Turpin et al., 2013). Thus, it is likely that the induction of the mucus pathway requires lactate and additional factors brought by S. thermophilus during its transit through the gut. It is possible that bioactive muco-inducer peptides may be produced by S. thermophilus in the gut as in yogurt. Indeed, Plaisancie et al. (2013, 2015) and Bruno et al. (2017) have shown that lactic acid bacteria of yogurt form small and functional peptides by hydrolyzing milk caseins, and some, such as peptide β-CN(94-123), significantly induce mucus production in vitro and in vivo. It may be informative to purify small peptides produced by S. thermophilus in the lumen that may act in synergy with lactate to induce mucus and reinforce the innate barrier and assess their function in relevant models.

We no longer observed induction of the mucus pathway in conventional mice harboring an endogenous microbiota in which S. thermophilus was sub-dominant (Figure 4). Regular gavage of these mice with S. thermophilus LMD-9Kana did not alter the number of goblet cells nor KLF4 protein levels in the colon (Figure 5) or ileum (data not shown). The O-glycosylation pattern of mucins plays an important role in intestinal homeostasis (Bergstrom and Xia, 2013) and we found that administration of S. thermophilus LMD-9Kana induced subtle changes in mucin O-glycan content in the colon. Indeed, we detected more sulfated structures in treated mice than in control animals. Of note, sulfated mucin-type O-glycans can exert a protective effect against colonic inflammation, as shown in chemically induced experimental colitis in mice (Tobisawa et al., 2010). It may thus be informative to evaluate whether and how S. thermophilus contributes to mucus maintenance in intestinal diseases or pathophysiological conditions in which the mucus barrier is altered. Indeed, it has been observed that the supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 has no effect on mucus in conventional mice, but prevents the deterioration of the colonic mucus layer associated with aging (van Beek et al., 2016).

Supplementation of conventional mice with S. thermophilus led to slight modifications of the levels of several short chain fatty acids (propionate, isobutyrate and isovalerate) and lactate was detectable in the cecum at higher levels than in non-treated animals, although the difference was small. Under normal conditions, lactate does not accumulate in the intestinal lumen of adults, because other bacteria consume it (Belenguer et al., 2011; Munoz-Tamayo et al., 2011). Higher lactate concentrations are found in exclusively breast-fed infants (Bridgman et al., 2017). In the gut, lactate has anti-microbial activity by acidifying the luminal fluid and through indirect mechanisms that influence the expression of colonization factors necessary for the commensalism of pathogens. Notably, lactate lowers the transcription of genes required for in vivo growth and catabolism of Campylobacter jejuni (Luethy et al., 2017). A lactate-rich environment inside the gut may also promote tolerance to commensal bacteria (Angelin et al., 2017) and attenuate pro-inflammatory pathways (Iraporda et al., 2015; Iraporda et al., 2016). Therefore, lactate possesses a wide panel of beneficial activities inside the gut that may feed microbial communities, fight pathogens, alleviate inflammatory processes, and strengthen the intestinal barrier through mucus production. We suggest that lactate production by S. thermophilus in the digestive tract may contribute to the microbiota trophic chain and stimulate the mucus pathway and mucus formation under specific conditions (old age, inflammation, etc.).

Overall, the lactose-degrading probiotic S. thermophilus adheres poorly to mucus and poorly degrades mucin sugars in vitro. We propose that lactate, produced in the gut by S. thermophilus may potentially induce pathways involved in mucus induction, as revealed using gnotobiotic rodents to study the novel functions of transient food-borne bacteria. This suggests that the consumption of fermented dairy products may reinforce mucosal integrity of the intestine. Although we did not observe mucus induction in a more sophisticated physiological context with a complex microbiota, we believe that this newly revealed S. thermophilus-driven function may be protective under certain conditions in which the mucus barrier is altered.

Author Contributions

MC-B, FR, EO-D, MT, and MM-B designed the project, obtained the financial support, and supervised the experiments. NF, LW, JR-B, BR-D, M-PD, M-LN, VL, VR, CC, M-LD-M, RL, and CR-M produced and/or analyzed the results. MT and MM-B wrote the article. All the authors have read and approved the last version of manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work is a part of the project BLaMI that was supported by Syndifrais-CNIEL (Paris, France).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.00980/full#supplementary-material

References

- Angelin A., Gil-de-Gomez L., Dahiya S., Jiao J., Guo L., Levine M. H., et al. (2017). Foxp3 reprograms T cell metabolism to function in low-glucose, high-lactate environments. Cell Metab. 25 1282–1293.e7. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenguer A., Holtrop G., Duncan S. H., Anderson S. E., Calder A. G., Flint H. J., et al. (2011). Rates of production and utilization of lactate by microbial communities from the human colon. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 77 107–119. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bene K. P., Kavanaugh D. W., Leclaire C., Gunning A. P., MacKenzie D. A., Wittmann A., et al. (2017). Lactobacillus reuteri surface mucus adhesins upregulate inflammatory responses through interactions with innate C-type lectin receptors. Front. Microbiol. 8:321. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yahia L., Mayeur C., Rul F., Thomas M. (2012). Growth advantage of Streptococcus thermophilus over Lactobacillus bulgaricus in vitro and in the gastrointestinal tract of gnotobiotic rats. Benef. Microbes 3 211–219. 10.3920/BM2012.0012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom K. S., Xia L. (2013). Mucin-type O-glycans and their roles in intestinal homeostasis. Glycobiology 23 1026–1037. 10.1093/glycob/cwt045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgman S. L., Azad M. B., Field C. J., Haqq A. M., Becker A. B., Mandhane P. J., et al. (2017). Fecal short-chain fatty acid variations by breastfeeding status in infants at 4 months: differences in relative versus absolute concentrations. Front. Nutr. 4:11. 10.3389/fnut.2017.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno J., Nicolas A., Pesenti S., Schwarz J., Simon J. L., Leonil J., et al. (2017). Variants of beta-casofensin, a bioactive milk peptide, differently modulate the intestinal barrier: in vivo and ex vivo studies in rats. J. Dairy Sci. 100 3360–3372. 10.3168/jds.2016-12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherbuy C., Darcy-Vrillon B., Morel M. T., Pegorier J. P., Duee P. H. (1995). Effect of germfree state on the capacities of isolated rat colonocytes to metabolize n-butyrate, glucose, and glutamine. Gastroenterology 109 1890–1899. 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90756-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherbuy C., Honvo-Houeto E., Bruneau A., Bridonneau C., Mayeur C., Duee P. H., et al. (2010). Microbiota matures colonic epithelium through a coordinated induction of cell cycle-related proteins in gnotobiotic rat. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 299 G348–G357. 10.1152/ajpgi.00384.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. (1987). Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162 156–159. 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90021-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva S., Robbe-Masselot C., Ait-Belgnaoui A., Mancuso A., Mercade-Loubiere M., Salvador-Cartier C., et al. (2014). Stress disrupts intestinal mucus barrier in rats via mucin O-glycosylation shift: prevention by a probiotic treatment. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 307 G420–G429. 10.1152/ajpgi.00290.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva S., Robbe-Masselot C., Raymond A., Mercade-Loubiere M., Salvador-Cartier C., Ringot B., et al. (2015). Spatial localization and binding of the probiotic Lactobacillus farciminis to the rat intestinal mucosa: influence of chronic stress. PLoS One 10:e0136048. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos W. M. (2017). Microbe profile: Akkermansia muciniphila: a conserved intestinal symbiont that acts as the gatekeeper of our mucosa. Microbiology 163 646–648. 10.1099/mic.0.000444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debarbouille M., Arnaud M., Fouet A., Klier A., Rapoport G. (1990). The sacT gene regulating the sacPA operon in Bacillus subtilis shares strong homology with transcriptional antiterminators. J. Bacteriol. 172 3966–3973. 10.1128/jb.172.7.3966-3973.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efsa Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). (2010). Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to live yoghurt cultures and improved lactose digestion (ID 1143, 2976) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 8:1763 10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO. (2002). Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Rome: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- Gardan R., Besset C., Guillot A., Gitton C., Monnet V. (2009). The oligopeptide transport system is essential for the development of natural competence in Streptococcus thermophilus strain LMD-9. J. Bacteriol. 191 4647–4655. 10.1128/JB.00257-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herve-Jimenez L., Guillouard I., Guedon E., Boudebbouze S., Hols P., Monnet V., et al. (2009). Postgenomic analysis of streptococcus thermophilus cocultivated in milk with Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus: involvement of nitrogen, purine, and iron metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 2062–2073. 10.1128/AEM.01984-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hols P., Hancy F., Fontaine L., Grossiord B., Prozzi D., Leblond-Bourget N., et al. (2005). New insights in the molecular biology and physiology of Streptococcus thermophilus revealed by comparative genomics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29 435–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao Y. P., Huang H. L., Lai W. W., Chung J. G., Yang J. H. (2009). Antiproliferative effects of lactic acid via the induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in a human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT). J. Dermatol. Sci. 54 175–184. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iraporda C., Errea A., Romanin D. E., Cayet D., Pereyra E., Pignataro O., et al. (2015). Lactate and short chain fatty acids produced by microbial fermentation downregulate proinflammatory responses in intestinal epithelial cells and myeloid cells. Immunobiology 220 1161–1169. 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iraporda C., Romanin D. E., Bengoa A. A., Errea A. J., Cayet D., Foligne B., et al. (2016). Local treatment with lactate prevents intestinal inflammation in the TNBS-induced colitis model. Front. Immunol. 7:651. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson H. E., Rodriguez-Pineiro A. M., Schutte A., Ermund A., Boysen P., Bemark M., et al. (2015). The composition of the gut microbiota shapes the colon mucus barrier. EMBO Rep. 16 164–177. 10.15252/embr.201439263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M. E., Jakobsson H. E., Holmen-Larsson J., Schutte A., Ermund A., Rodriguez-Pineiro A. M., et al. (2015). Normalization of host intestinal mucus layers requires long-term microbial colonization. Cell Host Microbe 18 582–592. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebouchi M., Galia W., Genay M., Soligot C., Lecomte X., Awussi A. A., et al. (2016). Implication of sortase-dependent proteins of Streptococcus thermophilus in adhesion to human intestinal epithelial cell lines and bile salt tolerance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100 3667–3679. 10.1007/s00253-016-7322-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan A., Bruneau A., Bensaada M., Philippe C., Bellaud P., Rabot S., et al. (2008). Increased induction of apoptosis by Propionibacterium freudenreichii TL133 in colonic mucosal crypts of human microbiota-associated rats treated with 1,2-dimethylhydrazine. Br. J. Nutr. 100 1251–1259. 10.1017/S0007114508978284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le D. T., Tran T. L., Duviau M. P., Meyrand M., Guerardel Y., Castelain M., et al. (2013). Unraveling the role of surface mucus-binding protein and pili in muco-adhesion of Lactococcus lactis. PLoS One 8:e79850. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis P., Flint H. J. (2017). Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 19 29–41. 10.1111/1462-2920.13589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luethy P. M., Huynh S., Ribardo D. A., Winter S. E., Parker C. T., Hendrixson D. R. (2017). Microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids modulate expression of Campylobacter jejuni determinants required for commensalism and virulence. mBio 8:e00407-17. 10.1128/mBio.00407-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie D. A., Jeffers F., Parker M. L., Vibert-Vallet A., Bongaerts R. J., Roos S., et al. (2010). Strain-specific diversity of mucus-binding proteins in the adhesion and aggregation properties of Lactobacillus reuteri. Microbiology 156 3368–3378. 10.1099/mic.0.043265-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens E. C., Lowe E. C., Chiang H., Pudlo N. A., Wu M., McNulty N. P., et al. (2011). Recognition and degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides by two human gut symbionts. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001221. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki T., Pedron T., Regnault B., Mulet C., Hara T., Sansonetti P. J. (2013). Epithelial cell proliferation arrest induced by lactate and acetate from Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium breve. PLoS One 8:e63053. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattar A. F., Teitelbaum D. H., Drongowski R. A., Yongyi F., Harmon C. M., Coran A. G. (2002). Probiotics up-regulate MUC-2 mucin gene expression in a Caco-2 cell-culture model. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 18 586–590. 10.1007/s00383-002-0855-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyrand M., Guillot A., Goin M., Furlan S., Armalyte J., Kulakauskas S., et al. (2013). Surface proteome analysis of a natural isolate of Lactococcus lactis reveals the presence of pili able to bind human intestinal epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12 3935–3947. 10.1074/mcp.M113.029066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Tamayo R., Laroche B., Walter E., Dore J., Duncan S. H., Flint H. J., et al. (2011). Kinetic modelling of lactate utilization and butyrate production by key human colonic bacterial species. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 76 615–624. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01085.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisancie P., Boutrou R., Estienne M., Henry G., Jardin J., Paquet A., et al. (2015). beta-Casein(94-123)-derived peptides differently modulate production of mucins in intestinal goblet cells. J. Dairy Res. 82 36–46. 10.1017/S0022029914000533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisancie P., Claustre J., Estienne M., Henry G., Boutrou R., Paquet A., et al. (2013). A novel bioactive peptide from yoghurts modulates expression of the gel-forming MUC2 mucin as well as population of goblet cells and Paneth cells along the small intestine. J. Nutr. Biochem. 24 213–221. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziwill-Bienkowska J. M., Le D. T., Szczesny P., Duviau M. P., Aleksandrzak-Piekarczyk T., Loubiere P., et al. (2016). Adhesion of the genome-sequenced Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris IBB477 strain is mediated by specific molecular determinants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100 9605–9617. 10.1007/s00253-016-7813-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziwill-Bienkowska J. M., Robert V., Drabot K., Chain F., Cherbuy C., Langella P., et al. (2017). Contribution of plasmid-encoded peptidase S8 (PrtP) to adhesion and transit in the gut of Lactococcus lactis IBB477 strain. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101 5709–5721. 10.1007/s00253-017-8334-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossez Y., Maes E., Lefebvre Darroman T., Gosset P., Ecobichon C., Joncquel Chevalier Curt M., et al. (2012). Almost all human gastric mucin O-glycans harbor blood group A, B or H antigens and are potential binding sites for Helicobacter pylori. Glycobiology 22 1193–1206. 10.1093/glycob/cws072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rul F. (2017). Fermented Foods. Yogurt: Microbiology, Organoleptic Properties and Probiotic Potential. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rul F., Ben-Yahia L., Chegdani F., Wrzosek L., Thomas S., Noordine M. L., et al. (2011). Impact of the metabolic activity of Streptococcus thermophilus on the colon epithelium of gnotobiotic rats. J. Biol. Chem. 286 10288–10296. 10.1074/jbc.M110.168666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicard J. F., Le Bihan G., Vogeleer P., Jacques M., Harel J. (2017). Interactions of intestinal bacteria with components of the intestinal mucus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7:387 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M., Wrzosek L., Ben-Yahia L., Noordine M. L., Gitton C., Chevret D., et al. (2011). Carbohydrate metabolism is essential for the colonization of Streptococcus thermophilus in the digestive tract of gnotobiotic rats. PLoS One 6:e28789. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobisawa Y., Imai Y., Fukuda M., Kawashima H. (2010). Sulfation of colonic mucins by N-acetylglucosamine 6-O-sulfotransferase-2 and its protective function in experimental colitis in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 285 6750–6760. 10.1074/jbc.M109.067082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas J., Wrzosek L., Bouznad N., Bouet S., Mayeur C., Noordine M. L., et al. (2013). Primocolonization is associated with colonic epithelial maturation during conventionalization. FASEB J. 27 645–655. 10.1096/fj.12-216861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpin W., Humblot C., Noordine M. L., Thomas M., Guyot J. P. (2012). Lactobacillaceae and cell adhesion: genomic and functional screening. PLoS One 7:e38034. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpin W., Humblot C., Noordine M. L., Wrzosek L., Tomas J., Mayeur C., et al. (2013). Behavior of lactobacilli isolated from fermented slurry (ben-saalga) in gnotobiotic rats. PLoS One 8:e57711. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek A. A., Sovran B., Hugenholtz F., Meijer B., Hoogerland J. A., Mihailova V., et al. (2016). Supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 prevents decline of mucus barrier in colon of accelerated aging Ercc1-/Delta7 mice. Front. Immunol. 7:408. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Herreweghen F., Van den Abbeele P., De Mulder T., De Weirdt R., Geirnaert A., Hernandez-Sanabria E., et al. (2017). In vitro colonisation of the distal colon by Akkermansia muciniphila is largely mucin and pH dependent. Benef. Microbes 8 81–96. 10.3920/BM2016.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga P., Gallini C. A., Beal C., Michaud M., Delaney M. L., DuBois A., et al. (2010). Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis fermented milk product reduces inflammation by altering a niche for colitogenic microbes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 18132–18137. 10.1073/pnas.1011737107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Cao H., Liu L., Wang B., Walker W. A., Acra S. A., et al. (2014). Activation of epidermal growth factor receptor mediates mucin production stimulated by p 40, a Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-derived protein. J. Biol. Chem. 289 20234–20244. 10.1074/jbc.M114.553800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrzosek L., Miquel S., Noordine M. L., Bouet S., Joncquel Chevalier-Curt M., Robert V., et al. (2013). Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii influence the production of mucus glycans and the development of goblet cells in the colonic epithelium of a gnotobiotic model rodent. BMC Biol. 11:61. 10.1186/1741-7007-11-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., Pritchard D. M., Yang X., Bennett E., Liu G., Liu C., et al. (2009). KLF4 gene expression is inhibited by the notch signaling pathway that controls goblet cell differentiation in mouse gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 296 G490–G498. 10.1152/ajpgi.90393.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.