Abstract

Out-of-pocket cost is an important barrier for utilization of health services and a contributor to health disparities. Medicare beneficiaries may face 20% coinsurance for screening colonoscopy with polyp removal or follow-up colonoscopy after a positive screening fecal test. Using an established microsimulation model, we predicted that waiving this coinsurance would result in 1.7 (-13 percent) fewer colorectal cancer deaths and US $17,000 (+0.6 percent ) higher colorectal cancer-related CMS costs per 1000 65-year-olds, when assuming an increase in colonoscopy screening rate from 60 to 70 percent. Waiving coinsurance would increase total cost by US $51,000 (+1.9 percent) per 1000 65-year-olds if screening participation were unchanged. The estimated screening benefits were comparable if fecal testing were the primary modality. Threshold analyses suggested that waiving coinsurance would already be cost-effective if screening rate increased from 60% to 60.6% (US $50,000 willingness-to-pay threshold), reflecting a likely favorable balance of health and cost impact.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States (US). It is estimated that, in 2017, over 135,000 new cases will be diagnosed, and more than 50,000 deaths due to CRC will occur (1). CRC screening may prevent CRC death and is therefore recommended for people age 50 years through age 75 years by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)(2).

Despite the overwhelming evidence for the effectiveness of screening (3), in 2015, only 61.1% of eligible people reported having received CRC testing consistent with current guidelines (4). Removing financial barriers is an effective approach to enhance the participation in CRC screening (5, 6). Provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 aimed to improve health care access and affordability of preventive services for all Americans (7), and eliminated cost-sharing for services such as CRC screening that are recommended with a Grade A or B by the USPSTF (8–12).

However, financial barriers for receipt of CRC screening persist despite the ACA. Medicare beneficiaries, the group with the highest age-related disease risk, receive full coverage with no deductible or coinsurance for a negative screening colonoscopy or a fecal test such as fecal immunochemical test (FIT). However, those without supplemental insurance face out-of-pocket liabilities when a polyp is detected and removed during the course of a screening colonoscopy, as the service is then classified by Medicare as diagnostic rather than preventive and is subject to a 20% coinsurance (13). Beneficiaries are also responsible for both the part B deductible and the 20% coinsurance for colonoscopy costs when it is performed after a positive fecal test, regardless of the outcome.

In the 2011–2012, 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 US Congressional sessions, bills (H.R. 4120, H.R. 1070 & S. 2348, and H.R. 1220 & S.624) were introduced to amend title XVIII of the Social Security Act to waive colonoscopy screening coinsurance for Medicare beneficiaries regardless of the findings of the procedure. On the basis of Medicare claims, it is estimated that Medicare spending on colonoscopies would increase by US $48 million annually (13). Due to lack of studies determining what the potential impact would be of waiving the coinsurance on screening participation and the corresponding savings in CRC treatment, those bills (14) were rejected.

To help inform future Medicare reimbursement policy, we estimated the potential impact of waiving Medicare coinsurance for screening colonoscopies with polyp removal, and for diagnostic colonoscopies performed after a positive FIT. Using a well-established microsimulation model, we evaluated several scenarios for the effect of such a waiver on take-up of screening to determine whether, and under what circumstances, it could prove cost-effective.

Methods

MISCAN-Colon

We used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis-Colon (MISCAN-Colon) model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of waiving coinsurance for every component of CRC screening from a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) perspective. MISCAN-Colon was developed by the Department of Public Health within Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and has been described extensively elsewhere (15, 16). It is part of the US National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Cancer intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) (17) and has been used to inform screening recommendations of the USPSTF (18, 19). In brief, the model generates, with random variation, the individual life histories for a large cohort to simulate the US population in terms of life expectancy and cancer risk. Each simulated person ages over time and may develop one or more adenomas that can progress from small (≤5 mm), to medium (6–9 mm) to large size (≥10 mm). Some adenomas develop into preclinical cancer, which may progress through stages I to IV. During each disease transition point, CRC may be diagnosed because of symptoms. Survival after clinical diagnosis is determined by the stage at diagnosis, the location of the cancer, and the person’s age. Some simulated life histories are altered by the effect of detecting and removing adenomas or diagnosing CRC in an earlier stage resulting in a better prognosis. Screening also results in over-diagnosis and over-treatment, and may have several complications, which are considered in the modelling. MISCAN-Colon quantifies the effectiveness and associated costs of CRC screening by comparing outcomes with and without a specific screening intervention. Further details about the model and its natural history assumptions are described in the online Appendix (20).

Analysis

We simulated an average-risk Medicare-eligible US population cohort of 65-year-olds of which 60% was up-to-date with screening according to the USPSTF guidelines (colonoscopy screening at ages 50 and 60 or annual FIT screening from age 50 to 64) at the age of 65 years, and then simulated potential increases in screening rate, benefits and costs due to waiving the Medicare coinsurance from age 65 years onward. Patients with a positive FIT result were referred to diagnostic colonoscopy. Detected adenomas were removed and followed by colonoscopy surveillance every 3–5 years depending on the number and the size of adenomas detected as recommended by current guidelines (21). Test characteristics were based on a study by Knudsen et al. (19). We assumed a FIT reimbursement of US $21.65 (22). Estimates of the costs of colonoscopies for screening, follow-up, and surveillance without lesion removal and any colonoscopy with lesion removal were obtained from an analysis of 2014 Medicare claims data from the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse, and updated to 2015 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index (CPI). CRC care costs were obtained from an analysis of 1998–2003 SEER-Medicare linked data (23) and updated to 2015 US dollars using the CPI. Detailed model assumptions regarding test characteristics, utility losses and costs can be seen in the Appendix Exhibit A1 (20).

Five scenarios were simulated with regards to coinsurance and screening rate, which were evaluated separately for FIT- and colonoscopy-based screening strategies. First, the ‘current state’ was simulated, in which 70% of the total population aged 50–75 years had received at least one screening, 60% is current with screening recommendations (4, 24, 25), 80% adhered to potential diagnostic and surveillance colonoscopy (26, 27), and the 20% coinsurance for screening colonoscopy with polypectomy and colonoscopy after a positive FIT result were intact (no supplemental insurance was taken into account)(see Appendix Exhibit A1 for more details on adherence assumptions as effective in each round (20)). In the second scenario, coinsurance for all participants was waived with no assumed effect on screening rate. In the third scenario, waiving coinsurance was assumed to lead to a 5 percentage point increase in completion of diagnostic colonoscopy after a positive FIT result and surveillance. In the fourth scenario, we simulated a 5 percentage point increase in both screening rate, adherence with diagnostic follow-up and surveillance adherence as a consequence of coinsurance removal. In this scenario, the percentage up-to-date with screening and ever screened increased to 65% and 73.75%, respectively (for similar relative reductions in the number not current with screening and never screened). In the fifth scenario, we simulated a 10-percentage point increase in screening rate, diagnostic follow-up and surveillance due to coinsurance removal, which resulted in 70% and 77.5% being up-to-date with screening and ever screened, respectively (Appendix Exhibit A1 (20)). The levels of increased screening participation simulated in the fourth and the fifth scenario match the effect seen with elimination of coinsurance for screening colonoscopies (11, 12, 28).

For all coinsurance and screening rate scenarios, and both the FIT- and colonoscopy-based screening strategies, we determined as main outcomes: the number of CRC cases and deaths, the number of colonoscopies potentially subject to coinsurance, the life-years (LYs) and the quality-adjusted LYs (QALYs) gained compared to no screening, and the associated costs. We applied the conventional 3% annual discount rate for all outcomes except for the number of CRC cases, deaths and number of colonoscopies with coinsurance requirements. In addition, because the true effect on screening participation from waiving coinsurance is unknown, we determined the threshold increase in screening rate at which full coverage of colonoscopy by CMS is cost-effective compared to the current state based on willingness to pay thresholds of US $100,000 and US $50,000 per QALY gained (29).

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analyses, we evaluated the robustness of our results to seven alternative assumptions: 1) 60% the cohort of 65-year-olds was previously screened once at age 55 using colonoscopy, and received colonoscopy screening at ages 65 and 75; 2) the cohort of 65-year-olds received no screening at all before the age of 65; 3) costs for colonoscopy were 10–75% higher (Appendix Exhibit A1 (20)); 4) treatment cost for the initial phases of stage III and IV disease and for the terminal phase of CRC care (all stages) were 10–75% higher (Appendix Exhibit A1 (20)); 5) the population that only participates in screening if coinsurances are waived (socioeconomically disadvantaged people without supplemental insurance) and the population that never participates have a 1.2-fold higher CRC incidence than the population that participates in CRC screening irrespectively of costs, based on the study of Oliphant et al. (30); 6) Test sensitivities of FIT and colonoscopy were lower (worst-case) or higher (best-case) than our base-case analyses (Appendix Exhibit A1 (20)), and 7) potential increases in screening rate, benefits and costs were simulated from age 50 onward.

Limitations

Our study has a few limitations to consider. First, the effect of waiving coinsurance on participation is not well-known because of paucity of published studies. We therefore evaluated several scenarios based on estimates of the effect of the coinsurance waiver for screening colonoscopies, and determined a threshold increase at which waiving the coinsurance is cost-effective. Second, CRC treatment costs derived from 1998–2003 SEER-Medicare linked data may underestimate treatment costs as therapy with monoclonal antibodies received FDA-approval after the period during which our cost estimates were derived. Therefore, we underestimated cost savings due to averted treatment expenses for cancer cases in our base-case analyses, and thus we explored the impact of higher treatment costs in our sensitivity analyses. Third, no up-to-date information was available on the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with supplemental insurance. Supplemental coverage may vary across packages and states. We assumed a 20% increase in costs for CMS for all colonoscopies with polypectomy and colonoscopies performed after a positive FIT upon waiving the coinsurance. This likely overestimated the increase in cost from CMS’ perspective and therefore the cost-effectiveness threshold of waiving coinsurance, as for people in Medicare Advantage, the private plans that receive premiums from CMS may already cover expenses. Likewise, the health impact from waiving coinsurance may mainly accrue from those without supplemental coverage (an estimated 14% in 2010 (31)), given those with additional insurance may have no financial benefit from the legislation change.

Results

Potential benefits and costs of waiving coinsurance

We estimated that, in the colonoscopy strategy at current adherence, 12.8 CRC deaths occur and 124.1 QALYs were gained per 1,000 65-year-olds compared to no screening (Exhibit 1). The total number of procedures per 1000 Medicare Beneficiaries was 1132, of which 410 (36%) were potentially subject to coinsurance requirements. We estimated the total lifetime costs for CMS, which included CRC screening, surveillance and treatment, to be US $2.675 million per 1000 65-year-olds (Appendix Exhibit A2 (20)).

EXHIBIT 1.

CRC Outcomes from a CMS perspective per 1,000 65-year-old Medicare Beneficiaries, by screening category, coinsurance requirement and screening rate scenario.Source: Authors analysis using MISCAN-Colon.

| Category Scenarioa |

CRC Cases | CRC Deaths | Colonoscopies with coinsurance requirements | LY gained | QALY gained | Total costs (million $) |

Incremental Costs/ QALY gained compared to the current state |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| --------------Undiscounted--------------- | -------------------------3% Discounted------------------------- | ||||||

| No screening | 60.1 | 26.6 | 60.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.276 | - |

| Colonoscopy | |||||||

| With coinsurance | |||||||

| Current state | 34.2 | 12.8 | 410* | 104.1 | 124.1 | 2.675 | - |

| Without coinsurance | |||||||

| No impact on adherence | 34.2 | 12.8 | 410 | 104.1 | 124.1 | 2.726 | - |

| With 5 percentage point increase in adherence diagnostic follow-up and surveillance. | 34.1 | 12.7 | 411 | 104.1 | 124.1 | 2.728 | 1,142,885 |

| With 5 percentage point increase in adherence first screening, diagnostic follow-up and surveillance. | 32.9 | 11.9 | 439 | 111.0 | 132.2 | 2.708 | 4,086 |

| With 10 percentage point increase in adherence first screening, diagnostic follow-up and surveillance. | 31.6 | 11.1 | 470 | 117.9 | 140.4 | 2.692 | 1,035 |

| FIT | |||||||

| With coinsurance | |||||||

| Current state | 39.5 | 14.0 | 357 | 99.4 | 115.9 | 2.743 | - |

| Without coinsurance | |||||||

| No impact on adherence | 39.5 | 14.0 | 357 | 99.4 | 115.9 | 2.785 | - |

| With 5 percentage point increase in adherence diagnostic follow-up and surveillance. | 39.2 | 13.9 | 368 | 100.1 | 116.7 | 2.783 | 48,606 |

| With 5 percentage point increase in adherence first screening, diagnostic follow-up and surveillance. | 38.5 | 13.2 | 391 | 106.2 | 123.7 | 2.772 | 3,747 |

| With 10 percentage point increase in adherence first screening, diagnostic follow-up and surveillance. | 37.3 | 12.4 | 427 | 112.9 | 131.6 | 2.758 | 974 |

Notes: In the current state, we assumed a 60% screening rate, an 80% adherence to diagnostic follow-up after a positive FIT, and an 80% adherence to surveillance. In the second scenario, coinsurance is waived without an effect on screening rate. In the third scenario, waiving coinsurance is assumed to lead to a 5 percentage point increase in adherence to diagnostic follow-up and surveillance. In the fourth and the fifth scenario, we simulated a 5 percentage point and 10 percentage point increase in screening rate, diagnostic follow-up and surveillance as a consequence of coinsurance removal, respectively.

The total number of colonoscopies in this scenario is 1132.

Abbreviations: LY = life-years; QALY = quality-adjusted life-years; CRC= colorectal cancer

The benefits of waiving coinsurance for a screening colonoscopy in which a polyp is removed varied with the assumed increase in participation. For the colonoscopy strategy, if there is no change in screening rate from waiving the coinsurance, the benefits of screening would not change, but the total costs of screening and treatment would increase to US $2.726 million (+ US $51,000; +1.9%) per 1000 65-year-olds (Exhibit 1). In contrast, a 5 percentage point increase in assumed screening rate with colonoscopy screening and surveillance decreased the number of CRC deaths by 0.9 (-6.4%), accompanied by an increase of US $33,000 (+1.2%) in total cost per 1000 65-year-olds, with a cost-effectiveness ratio of US $4,086 compared to the current state. A 10 percentage point increase in screening and surveillance rate decreased deaths even further by a total 1.7 (-13%), increased cost by only US $17,000 (+0.6%), resulting in a cost-effectiveness ratio of US $1,035 compared to the current state.

The potential benefits and costs of waiving all coinsurance for CRC screening were comparable between a FIT-based strategy and a colonoscopy-based strategy (Exhibit 1). Of special interest is the scenario in which a 5 percentage point increase in adherence to diagnostic follow-up and surveillance was assumed as a consequence of waiving coinsurance. This resulted in a cost-effectiveness ratio of US $48,606 compared to the current state (Exhibit 1), suggesting that even if only adherence to diagnostic follow-up and surveillance would increase by 5 percentage point while adherence to primary FIT screening is unaffected, waiving the coinsurance would be cost-effective.

Waiving coinsurance was estimated to initially increase costs, but led to cost savings after a decade due to averted CRC cases (Appendix Exhibit A3 (20)). The estimated increase in per person costs was slightly higher for the colonoscopy strategies compared to FIT strategies (Appendix Exhibit A3 (20)).

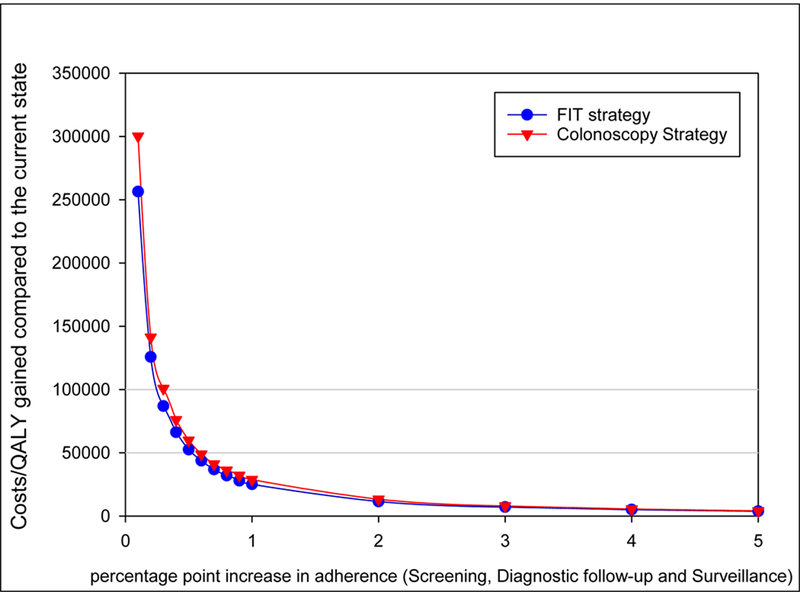

Threshold determination

Using a willingness to pay threshold of US $100,000, it was estimated that waiving all coinsurance would be cost-effective if it increases screening participation from 60% to 60.4% in a colonoscopy-based screening protocol and from 60% to 60.3% in a FIT-based screening protocol (Exhibit 2). When a willingness to pay threshold of US $50,000 was applied, the thresholds for both the colonoscopy and the FIT strategy were 0.6 percentage point, suggesting that if the screening rate would increase from 60% to 60.6%, waiving coinsurance would be cost-effective.

EXHIBIT 2.

Predicted increases in costs per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained if coinsurance for colorectal cancer screening were waived, by percentage-point increase in adherence to screening, diagnostic follow-up, and surveillance.

Sensitivity analyses

As shown in Exhibit 3, several sensitivity analyses affected the percentage point increase in screening rate at which waiving all coinsurance is cost-effective. First, in the sensitivity analysis that assumed one previous colonoscopy screening at age 55 or no screening before the age of 65, the thresholds at which waiving coinsurance was cost-effective increased to 0.9 and 1.8 percentage point, respectively. Second, in the sensitivity analysis that assumed higher colonoscopy costs, the threshold was increased up to 1.3 percentage point. Third, if we simulated potential increases in screening rate, benefits and costs from age 50 years rather than age 65 years onward, this approximately doubled the threshold. Sensitivity analyses evaluating the effect of alternative assumptions for treatment costs, higher CRC risk in additional participants and test sensitivities demonstrated that these assumptions minimally affected the percentage point increase in screening rate at which waiving all coinsurance is cost-effective. The increase in screening rate that is needed to make waiving the coinsurance cost-effective did not exceeded 1.8 percentage point in any of the sensitivity analysis.

EXHIBIT 3.

Threshold percentage point increase in CRC screening rate, diagnostic follow-up and surveillance at which waiving coinsurance for Medicare Beneficiaries is cost-effective from a CMS perspective for a colonoscopy-based strategy and a FIT-based strategy with alternative model assumptions (3% discounted).

| Colonoscopy |

FIT |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to pay Threshold | US $100,000 | US $50,000 | US $100,000 | US $50,000 |

| Base-Case | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| One previous screening at age 55a | 0.5 | 0.9 | - | - |

| Without Previous Screeningab | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Higher Colonoscopy costs | ||||

| 10% | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| 25% | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| 50% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| 75% | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Higher Treatment costsc | ||||

| 10% | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| 25% | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| 50% | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| 75% | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Higher CRC risk in additional participants | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Worst-case test sensitivity | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Best-case test sensitivity | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Population of 50 year olds | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

Source: Authors analysis using MISCAN-Colon

Notes: We assumed a 60% current screening rate and an 80% adherence to diagnostic follow-up and surveillance in the current state. a. Screening at ages 65 and 75. b. No screening before the age of 65 was assumed. c. a 10%, 25%, 50% or 75% higher treatment costs for initial phase stage III and IV and for Terminal phase CRC care (all stages) was simulated.

Cost per QALY gained compared to the current state remained below US $25,000 in every scenario if waiving coinsurance resulted in an increase in screening rate (Appendix Exhibit A3 (20)). Strikingly, in the sensitivity analysis that assumed at least 25% higher CRC care costs, the increase in costs of waiving coinsurance was totally offset by savings in CRC care costs if it would result in a 10% point increase in screening rate, such that waiving coinsurance would be cost saving (Appendix Exhibits A4 & A5 (20)).

Discussion

Colorectal cancer screening is an effective prevention method, and removing financial barriers has been identified as a promising intervention for enhancing the participation in CRC screening (5, 6). While we did not estimate the effect on participation of waiving coinsurance for screening colonoscopies with polyp removal or colonoscopies performed after a positive FIT, we showed that the policy may be cost-effective if it would increase the screening rate from 60% to 60.6% in Medicare beneficiaries, using a willingness to pay threshold of US $50,000. Even if waiving all coinsurance for CRC screening would not result in an increase in screening rate, total costs for Medicare would increase by only 1.9% for the colonoscopy strategy and 1.5% for the FIT strategy (3% discounted). Strikingly, our sensitivity analyses demonstrated that if the actual costs are 25% higher for initial phases of care for stage III and IV and for terminal disease than our base-case estimates, waiving coinsurance would be cost saving if it would increase screening rates to 70%.

Literature on cost and health impact of waiving coinsurance

We are aware of one previous study that examined the potential budget impact of waiving coinsurance for all screening-related colonoscopies. Howard et al. reported a 10% increase in total colonoscopy costs from waiving coinsurance for a diagnostic colonoscopy after a positive FIT and a positive screening colonoscopy (13). The increases in total colonoscopy costs in our analyses were 7.3% (costs screening, diagnostic, surveillance and associated complications) in the colonoscopy strategy and 11.8% (costs diagnostic, surveillance and associated complications) for the FIT strategy if waiving coinsurance does not increase screening rate. However, the study by Howard et al. focused only on colonoscopy costs and did not consider cost savings from averted CRC cases (13). The strength of our study is that we also considered the potential impact of waiving coinsurance on screening behavior and estimated costs of the entire CRC screening process, including screening, diagnosis, surveillance, complications and care, thereby placing the increase in costs from waiving coinsurance in a more complete context.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the potential benefits of waiving coinsurance for a colonoscopy with polypectomy and for a follow-up colonoscopy after a positive FIT. The predicted health benefits of the waiver depend on the assumed impact on screening rate. As a potential source of information for the expected impact, several studies have looked at the effect of similar legislation changes in which coinsurances were removed for screening colonoscopies. Khatami et al. reported that waiving coinsurance for a negative screening colonoscopy resulted in an annual increase in colonoscopy use of 8.0% to 9.5% in employees of the University of Texas System (28), a relative increase of 18%. Hamman and Kapinos found a 4.0 percentage point increase in annual colonoscopy rates in 66–75-year-old men within one year of enacting the ACA. They found even larger increases among socioeconomically disadvantaged men (12). Fedewa et al. described a 9.8 percentage point increase in CRC screening prevalence after mandates on coverage of preventive care from the ACA came into effect in Medicare beneficiaries by comparing 2013 to 2008 NHIS data (11). However, it is important to note that the ACA impacted more factors than cost-sharing alone, that may also influence screening participation, such as a free annual wellness visit and a temporary primary care bonus for physicians.

In contrast, some studies found no effect of the elimination of cost-sharing for screening colonoscopies on participation in CRC screening (32–34), despite the fact that financial concerns is one of the most reported barriers for CRC screening. Substantial financial barriers may persist despite ACA provisions (a predicted 36% of procedures is still subject to coinsurance requirements), reflecting the complexity of current reimbursement policy for both patients and providers. Other factors such as the need for time off work, family responsibilities, transportation, and fear or other perceptions of the screening test also affect screening participation (35, 36).

Policy implications

We showed that waiving coinsurances will be cost-effective even with a modest increase in screening rate of 0.6 percentage points, assuming a current screening rate of 60%. By fully reimbursing all colonoscopies used in screening regardless of findings or indication, a clear and consistent message can be communicated, which may be a stimulus in itself for screening participation besides reducing financial barriers. In general, FIT screening was associated with a lower number of procedures subject to coinsurance. If FIT screening becomes more popular in the United States similar to trends observed in several settings (37, 38), the costs of waiving the coinsurance will be even lower.

It is likely that the waiver would primarily affect the out-of-pocket costs of Medicare beneficiaries from low socioeconomic status background, who more often lack Medigap and supplemental insurance. Medicare beneficiaries from a very low socioeconomic status background are eligible for Medicaid and may be protected from coinsurance in the 32 states that expanded Medicaid coverage (39). However, in the remaining 19 states, people from low socioeconomic groups are neither dual-eligible nor have supplemental insurance. This means that waiving coinsurance may also contribute to reducing CRC health disparities in the US (40). Health disparities are larger for the US than many other Western countries (41) and reducing health disparities is an important Healthy People 2020 objective (42).

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study informs the public debate and policy on the balance of costs and benefits of waiving Medicare coinsurance for colonoscopy screening in instances where a polyp is removed or the procedure is a follow-up to a positive FIT result. Our analyses estimates that waiving coinsurance is cost-effective at a willingness to pay threshold of US $50,000 if screening rates increase from 60% to 60.6%, suggesting a likely very favorable balance of health and cost impact.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.American Cancer Society, Cancer Statistics Center. 2017 [cited 2017 February 21]; Available from: https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/?_ga=1.33682849.1877282425.1465291457#/cancer-site/Colorectum.

- 2.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW Jr, .arcia FA, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016. June 21;315(23):2564–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holme O, Bretthauer M, Fretheim A, Odgaard-Jensen J, Hoff G. Flexible sigmoidoscopy versus faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. October 01(9):CD009259.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health interview Survey (NHIS) 2015; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

- 5.Senore C, Inadomi J, Segnan N, Bellisario C, Hassan C. Optimising colorectal cancer screening acceptance: a review. Gut. 2015. July;64(7):1158–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RM, Woolf SH, Cunningham TD, Johnson RE, Krist AH, Rothemich SF, et al. The relative importance of patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2010. May;38(5):499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, Musco T. Changes in Self-reported Insurance Coverage, Access to Care, and Health Under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015. July 28;314(4):366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamman MK, Kapinos KA. Colorectal Cancer Screening and State Health Insurance Mandates. Health Econ. 2016. February;25(2):178–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richman I, Asch SM, Bhattacharya J, Owens DK. Colorectal Cancer Screening in the Era of the Affordable Care Act. J Gen Intern Med. 2016. March;31(3):315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wharam JF, Zhang F, Landon BE, LeCates R, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Nationwide High-deductible Health Plan Before and After the Affordable Care Act. Med Care. 2016. May;54(5):466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fedewa SA, Goodman M, Flanders WD, Han X, Smith RA, E MW, et al. Elimination of cost-sharing and receipt of screening for colorectal and breast cancer. Cancer. 2015. September 15;121(18):3272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamman MK, Kapinos KA. Affordable Care Act Provision Lowered Out-Of-Pocket Cost And Increased Colonoscopy Rates Among Men In Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015. December;34(12):2069–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard DH, Guy GP Jr,Ekwueme DU Eliminating cost-sharing requirements for colon cancer screening in Medicare. Cancer. 2014. December 15;120(24):3850–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.H.R. 1220 — 114th Congress: Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act of 2015. www.GovTrack.us.2015; [cited 2016 October 24]; Available from: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/hr1220.

- 15.van Hees F, Habbema JD, Meester RG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG. Should colorectal cancer screening be considered in elderly persons without previous screening? A cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014. June 3;160(11):750–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, Habbema JD, Kuipers EJ. Effect of rising chemotherapy costs on the cost savings of colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009. October 21;101(20):1412–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET). Colorectal cancer model profiles. National Cancer Institute. 2015. [cited 2016 November 24]; Available from: https://cisnet.cancer.gov/colorectal/profiles.html.

- 18.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Wilschut J, van Ballegooijen M, Kuntz KM. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008. November 4;149(9):659–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, Naber SK, Doria-Rose VP, Pabiniak C, et al. Estimation of Benefits, Burden, and Harms of Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies: Modeling Study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016. June 21;315(23):2595–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 21.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012. September;143(3):844–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.2015. Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files.html.

- 23.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, Warren JL, Topor M, Meekins A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008. May 7;100(9):630–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabatino SA, White MC, Thompson TD, Klabunde CN,Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Cancer screening test use - United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015. May 8;64(17):464–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use--United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013. November 8;62(44):881–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colquhoun P, Chen HC, Kim JI, Efron J, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, et al. High compliance rates observed for follow up colonoscopy post polypectomy are achievable outside of clinical trials: efficacy of polypectomy is not reduced by low compliance for follow up. Colorectal Disease. 2004;6(3):158–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, Lederle FA, Bond JH, Mandel JS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013. September 19;369(12):1106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khatami S, Xuan L, Roman R, Zhang S, McConnel C, Halm EA, et al. Modestly increased use of colonoscopy when copayments are waived. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012. July;10(7):761–6 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grosse SD. Assessing cost-effectiveness in healthcare: history of the $50,000 per QALY threshold. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008. April;8(2):165–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliphant R, Brewster DH, Morrison DS. The changing association between socioeconomic circumstances and the incidence of colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2011. May 24;104(11):1791–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 2010 Cost and Use file. [cited 2017 July 4]; Available from: http://kff.org/report-section/a-primer-on-medicare-what-types-of-supplemental-insurance-do-beneficiaries-have/.

- 32.Han X, Robin Yabroff K, Guy GP Jr, Zheng Z, Jemal A. Has recommended preventive service use increased after elimination of cost-sharing as part of the Affordable Care Act in the United States? Prev Med. 2015. September;78:85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper GS, Kou TD, Schluchter MD, Dor A, Koroukian SM. Changes in Receipt of Cancer Screening in Medicare Beneficiaries Following the Affordable Care Act. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016. May;108(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta SJ, Polsky D, Zhu J, Lewis JD, Kolstad JT, Loewenstein G, et al. ACA-mandated elimination of cost sharing for preventive screening has had limited early impact. Am J Manag Care. 2015. July;21(7):511–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medina GG, McQueen A, Greisinger AJ, Bartholomew LK, Vernon SW. What would make getting colorectal cancer screening easier? Perspectives from screeners and nonscreeners. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:895807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meissner HI, Klabunde CN, Breen N, Zapka JM. Breast and colorectal cancer screening: U.S. primary care physicians’ reports of barriers. Am J Prev Med. 2012. December;43(6):584–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta SJ, Jensen CD, Quinn VP, Schottinger JE, Zauber AG, Meester R, et al. Race/Ethnicity and Adoption of a Population Health Management Approach to Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Community-Based Healthcare System. J Gen Intern Med. 2016. November;31(11):1323–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramanian S, Bobashev G, Morris RJ. When budgets are tight, there are better options than colonoscopies for colorectal cancer screening. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010. September;29(9):1734–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser Family Foundation Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision [cited 2017 July 4]; Available from: http://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act.

- 40.Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Zauber AG. Colorectal Cancer Health Disparities and the Role of US Law and Health Policy. Gastroenterology. 2016. May;150(5):1052–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM. Access, affordability, and insurance complexity are often worse in the United States compared to ten other countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013. Dec;32(12):2205–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Healthy People 2020. [cited 2017 February 21]; Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.