Abstract

The Baltic Sea is one of the world’s largest brackish water bodies and is characterised by pronounced physicochemical gradients where microbes are the main biogeochemical catalysts. Meta-omic methods provide rich information on the composition of, and activities within, microbial ecosystems, but are computationally heavy to perform. We here present the Baltic Sea Reference Metagenome (BARM), complete with annotated genes to facilitate further studies with much less computational effort. The assembly is constructed using 2.6 billion metagenomic reads from 81 water samples, spanning both spatial and temporal dimensions, and contains 6.8 million genes that have been annotated for function and taxonomy. The assembly is useful as a reference, facilitating taxonomic and functional annotation of additional samples by simply mapping their reads against the assembly. This capability is demonstrated by the successful mapping and annotation of 24 external samples. In addition, we present a public web interface, BalticMicrobeDB, for interactive exploratory analysis of the dataset.

Subject terms: Genome informatics, Environmental sciences, Water microbiology, DNA sequencing, Metagenomics

Background & Summary

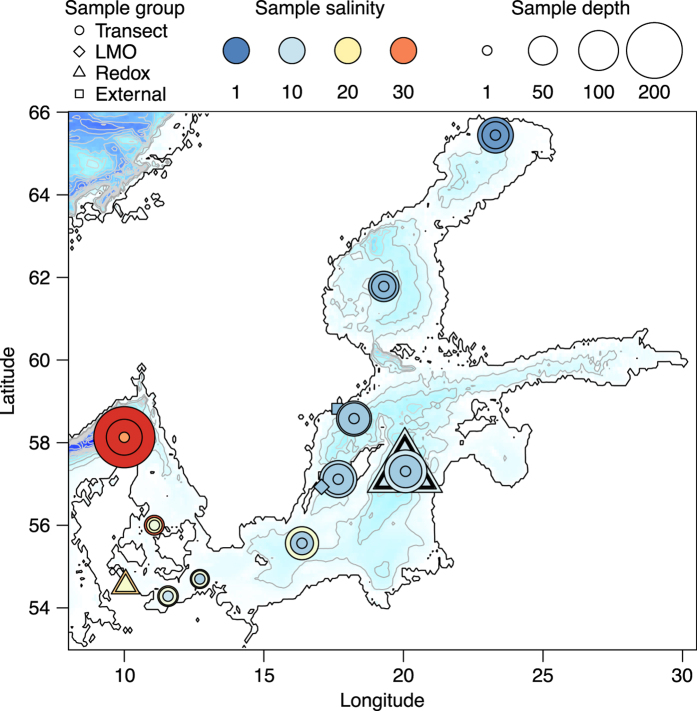

The Baltic Sea is a semi-enclosed inland sea characterized by strong physicochemical gradients, in particular horizontal and vertical salinity and oxygen gradients, and pronounced seasonal dynamics1. This ecosystem is also heavily impacted by anthropogenic eutrophication, manifested in e.g. harmful phytoplankton blooms and large areas with anoxic bottom waters2. Due to their key roles in biogeochemical cycles, microbial communities are particularly interesting to study in this ecosystem3–11. One of the most comprehensive methods to characterize the taxonomic and functional composition of microbial communities is through metagenomics, and specifically by metagenomic assembly, which enables high precision and sensitivity for both taxonomic and functional annotation12. These annotations can be quantified in individual samples by mapping short reads from samples that either were included in the assembly or constitute external samples. For some microbiomes, particularly those associated with the human body, extensive sequencing efforts have been undertaken to construct reference gene catalogues that are publicly available and can be utilized by others13–15. Large-scale metagenomic datasets also exist for the global ocean, such as the Tara Oceans dataset15. However, although the brackish Baltic Sea is composed of a mixture of marine- and freshwater like lineages3,5,7,10, these are genetically distinct from their relatives8, which hinders efficient read mapping to fresh- and marine water metagenomes. We here present a Baltic Sea metagenome co-assembly (BARM; BAltic sea Reference Metagenome) with annotated genes constructed from three sets of samples, selected to cover variation over geography, depth and season (Table 1 (available online only), Fig. 1; Data Citation 1).

Table 1. Sample summary.

| Sample Group | Sample | Station | Sampling Depth (m) | Sampling Date | Filter-size (μm) | Prefiltration size (μm) | Latitude | Longitude | Salinity (psu) | Oxygen (μmol/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Important contextual parameters for the samples, which were used to construct the co-assembly. | ||||||||||

| Lmo | 120314 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-03-14 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.7 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120322 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-03-22 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.9 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120328 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-03-28 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120403 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-04-03 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120416 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-04-16 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.7 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120419 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-04-19 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.7 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120423 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-04-23 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.7 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120507 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-05-07 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.6 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120516 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-05-16 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.4 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120521 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-05-21 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120531 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-05-31 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120604 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-06-04 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120613 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-06-13 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120619 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-06-19 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120628 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-06-28 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.4 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120705 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-07-05 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120709 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-07-09 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120717 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-07-17 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120802 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-08-02 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120806 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-08-06 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120813 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-08-13 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120820 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-08-20 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120823 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-08-23 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120828 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-08-28 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.1 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120903 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-09-03 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120910 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-09-10 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.1 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120920 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-09-20 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.4 | not collected |

| Lmo | 120924 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-09-24 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121001 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-10-01 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.4 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121004 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-10-04 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.3 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121015 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-10-15 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121022 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-10-22 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121028 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-10-28 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121105 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-11-05 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121123 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-11-23 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.5 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121128 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-11-28 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.4 | not collected |

| Lmo | 121220 | LMO | 2.0 | 2012-12-20 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 56.9384 | 17.062 | 6.2 | not collected |

| Redox | P2236_101 | TF0271 | 110.0 | 2014-10-26 | 3.0 | - | 57.3222 | 20.0506 | 10.9796 | 23.96521144 |

| Redox | P2236_102 | TF0271 | 110.0 | 2014-10-26 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 57.3222 | 20.0506 | 10.9796 | 23.96521144 |

| Redox | P2236_103 | TF0271 | 120.0 | 2014-10-26 | 3.0 | - | 57.3222 | 20.0506 | 11.282 | 5.9394045 |

| Redox | P2236_104 | TF0271 | 120.0 | 2014-10-26 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 57.3222 | 20.0506 | 11.282 | 5.9394045 |

| Redox | P2236_105 | TF0271 | 140.0 | 2014-10-26 | 3.0 | - | 57.3222 | 20.0506 | 11.7535 | 0.0 |

| Redox | P2236_106 | TF0271 | 140.0 | 2014-10-26 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 57.3222 | 20.0506 | 11.7535 | 0.0 |

| Redox | P2236_107 | TF0271 | 200.0 | 2014-10-26 | 3.0 | - | 57.3222 | 20.0506 | 12.1052 | 0.0 |

| Redox | P2236_108 | TF0271 | 200.0 | 2014-10-26 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 57.3222 | 20.0506 | 12.1052 | 0.0 |

| Redox | P2236_109 | Boknis Eck | 10.0 | 2014-09-23 | 3.0 | - | 54.5381 | 10.0478 | 16.276 | 276 |

| Redox | P2236_110 | Boknis Eck | 10.0 | 2014-09-23 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 54.5381 | 10.0478 | 16.276 | 276 |

| Redox | P2236_111 | Boknis Eck | 25.0 | 2014-09-23 | 3.0 | - | 54.5381 | 10.0478 | 25.082 | 0 |

| Redox | P2236_112 | Boknis Eck | 25.0 | 2014-09-23 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 54.5381 | 10.0478 | 25.082 | 0 |

| Redox | P2236_113 | TF0271 | 139.0 | 2014-10-18 | 0.2 | - | 57.3228 | 20.0606 | 11.7173 | 0 |

| Redox | P2236_114 | TF0271 | 100.0 | 2014-10-18 | 0.2 | - | 57.3228 | 20.0606 | 10.5491 | 41.53 |

| Transect | P1994_116 | MO7 | 2.8 | 2014-06-04 | 0.2 | - | 54.6979 | 12.7047 | 8.325 | 333.16 |

| Transect | P1994_117 | MO7 | 12.7 | 2014-06-04 | 0.2 | - | 54.6979 | 12.7047 | 14.969 | 268.41 |

| Transect | P1994_118 | MO7 | 19.3 | 2014-06-04 | 0.2 | - | 54.6979 | 12.7047 | 16.415 | 240.72 |

| Transect | P1994_101 | AT1 | 1.8 | 2014-06-05 | 0.2 | - | 58.1323 | 10 | 28.05 | 288.5 |

| Transect | P1994_102 | AT1 | 80.1 | 2014-06-05 | 0.2 | - | 58.1323 | 10 | 34.914 | 281.36 |

| Transect | P1994_103 | AT1 | 241.7 | 2014-06-05 | 0.2 | - | 58.1323 | 10 | 35.081 | 273.77 |

| Transect | P1994_110 | MO3 | 2.9 | 2014-06-06 | 0.2 | - | 56.867 | 11.4339 | 14.526 | 303.69 |

| Transect | P1994_111 | MO3 | 11.4 | 2014-06-06 | 0.2 | - | 56.867 | 11.4339 | 17.613 | 308.15 |

| Transect | P1994_112 | MO3 | 20.8 | 2014-06-06 | 0.2 | - | 56.867 | 11.4339 | 31.943 | 190.7 |

| Transect | P1994_113 | MO6 | 1.7 | 2014-06-07 | 0.2 | - | 54.2821 | 11.568 | 10.28 | 316.64 |

| Transect | P1994_114 | MO6 | 16.3 | 2014-06-07 | 0.2 | - | 54.2821 | 11.568 | 14.676 | 283.14 |

| Transect | P1994_115 | MO6 | 22.6 | 2014-06-07 | 0.2 | - | 54.2821 | 11.568 | 20.323 | 194.72 |

| Transect | P1994_119 | S6 | 3.0 | 2014-06-08 | 0.2 | - | 55.5659 | 16.3665 | 7.577 | 342.54 |

| Transect | P1994_120 | S6 | 30.3 | 2014-06-08 | 0.2 | - | 55.5659 | 16.3665 | 7.661 | 339.86 |

| Transect | P1994_121 | S6 | 66.6 | 2014-06-08 | 0.2 | - | 55.5659 | 16.3665 | 15.73 | 16.52 |

| Transect | P1994_104 | AT3 | 1.4 | 2014-06-09 | 0.2 | - | 57.3057 | 20.0766 | 6.744 | 380.95 |

| Transect | P1994_105 | AT3 | 65.4 | 2014-06-09 | 0.2 | - | 57.3057 | 20.0766 | 7.226 | 317.98 |

| Transect | P1994_106 | AT3 | 116.5 | 2014-06-09 | 0.2 | - | 57.3057 | 20.0766 | 10.862 | 9.38 |

| Transect | P1994_125 | S10 | 2.4 | 2014-06-10 | 0.2 | - | 61.7829 | 19.2952 | 5.456 | 391.22 |

| Transect | P1994_126 | S10 | 33.9 | 2014-06-10 | 0.2 | - | 61.7829 | 19.2952 | 5.462 | 393.45 |

| Transect | P1994_127 | S10 | 55.8 | 2014-06-10 | 0.2 | - | 61.7829 | 19.2952 | 5.566 | 364.87 |

| Transect | P1994_107 | AT4 | 1.8 | 2014-06-12 | 0.2 | - | 65.446 | 23.2973 | 2.442 | 389.88 |

| Transect | P1994_108 | AT4 | 42.3 | 2014-06-12 | 0.2 | - | 65.446 | 23.2973 | 3.04 | 414.89 |

| Transect | P1994_109 | AT4 | 78.7 | 2014-06-12 | 0.2 | - | 65.446 | 23.2973 | 3.146 | 401.05 |

| Transect | P1994_122 | S7 | 1.9 | 2014-06-16 | 0.2 | - | 58.5849 | 18.2327 | 6.742 | 345.22 |

| Transect | P1994_123 | S7 | 60.5 | 2014-06-16 | 0.2 | - | 58.5849 | 18.2327 | 7.248 | 338.08 |

| Transect | P1994_124 | S7 | 76.5 | 2014-06-16 | 0.2 | - | 58.5849 | 18.2327 | 9.221 | 17.42 |

| Transect | P1994_128 | TF245 | 3.0 | 2014-06-17 | 0.2 | - | 57.1162 | 17.6642 | 7.05 | 339.42 |

| Transect | P1994_129 | TF245 | 55.9 | 2014-06-17 | 0.2 | - | 57.1162 | 17.6642 | 7.304 | 343.44 |

| Transect | P1994_130 | TF245 | 85.7 | 2014-06-17 | 0.2 | - | 57.1162 | 17.6642 | 8.902 | 27.69 |

Figure 1. A map showing the locations for all stations where samples were taken.

The three sample groups included in the assembly (Transect, LMO and Redoxcline) are displayed together with the external sample set20 (External), all groups indicated with different markers. The colour of the marker indicates the salinity of the water sample while the size indicates the depth at which it was taken. The background color indicates depth (from white to dark blue), with contour lines drawn with 50 m intervals. The map was generated using the Marmap package36 in R37 with bathymetric data from the ETOPO1 dataset hosted on the NOAA server38.

After preprocessing of the reads, the 81 samples combined contained 586 billion bases in 2.6 billion read pairs. To allow the assembly of genes also from genomes having low abundance in individual samples, data from all samples were co-assembled. The resulting co-assembly consisted of 14 billion bases distributed over 22 million contigs. Out of these contigs, 2.4 million contigs were longer or equal to 1 kilobase. Functional and taxonomic annotation of genes is computationally demanding. For this reason, and since longer contigs were deemed to be more trustworthy, only genes found on the contigs >1 kilobase were subjected to functional and taxonomic annotations; 6.8 million genes were found on these.

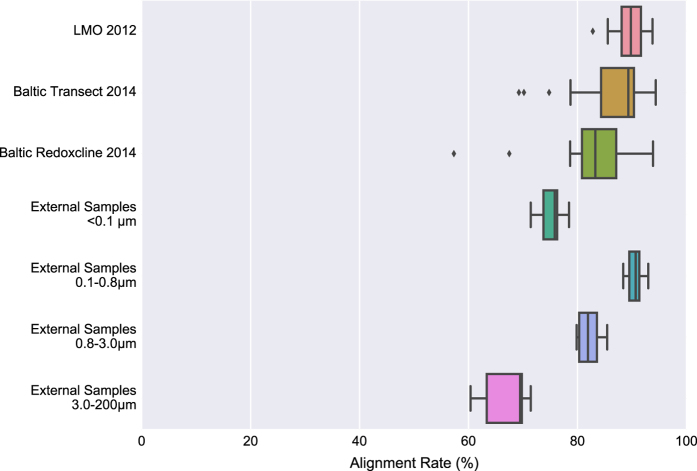

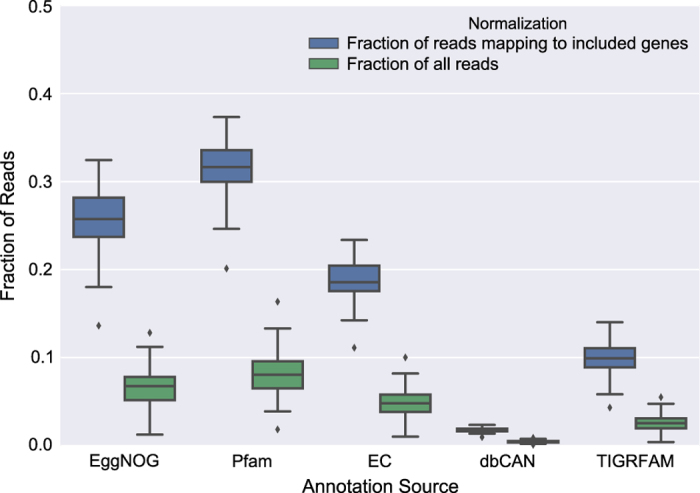

For functional analysis, several database sources were chosen; Pfam16, TIGRFAM (http://www.jcvi.org/cgi-bin/tigrfams/index.cgi), EggNOG17 and dbCAN18. Additionally, enzyme commission (EC) numbers19 were extracted based on the EggNOG assignments. Through mapping, the short reads were then used to quantify the individual genes over all the different samples, which were summarized per annotation identifier (ID) for each respective annotation source. The mapping rates for the different sample groups and annotation sources are summarized in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, where in Fig. 2 also 24 samples from a published metagenomic study20 (Data Citation 2) of the Baltic Sea are included to illustrate the capabilities for BARM to work as a reference gene catalogue for the Baltic Sea.

Figure 2. Mapping rates divided on different sample groups.

Mapping rates are calculated by Bowtie2 (ref. 30) as the “overall alignment rate”. The three first sample groups; LMO 2012 (N=37, 0.2–3.0 μm), Baltic Transect 2014 (N=30, >0.2 μm) and Baltic Redoxcline 2014 (N=6, 0.2–3.0 μm; N=6, >3.0 μm; N=2, >0.2 μm) were included in the assembly, while the four last sample groups; External Samples <0.1 μm (N=6), External Samples 0.1–0.8 μm (N=6), External Samples 0.8–3.0 μm (N=6) and External Samples 3.0–200 μm (N=6) were not. The size intervals of the external samples indicate filter pore sizes used to tentatively separate viruses, free-living prokaryotes, and small and larger particles as well as Eukaryotic cells, respectively34. Created using Matplotlib39 and Seaborn40.

Figure 3. Fraction of reads mapping to genes annotated with respective database.

Only genes identified on contigs longer than 1 kilobase were subjected to annotation, defining the ‘included genes’ category. N=81 for all categories. Created using Matplotlib39 and Seaborn40.

Along with the dataset, a public web interface (BalticMicrobeDB) was constructed to facilitate exploratory analysis of the data (https://barm.scilifelab.se). Through this it is possible to view counts of functional and taxonomic annotations over the different sample groups. Moreover, it is possible to search for functional annotations based on their descriptive texts and choose to view or download the counts for only those matching the search query.

The annotated assembly presented here is a rich resource for further exploitation of the published datasets, facilitated through the web interface, but could also function as a reference metagenome assembly for the Baltic Sea, decreasing the computational demands for the analysis of new metagenome and metatranscriptome samples, and serve as reference for metaproteome analyses.

Methods

Sampling, DNA Extraction and Sequencing

The thirty seven surface-water (2 m depth) samples from the 2012 time series (March to December) from the Linneaus Microbial Observatory (LMO), station located 10 km off the east coast of Öland, and where the maximum depth is 47 m, have been described in Hugerth et al. (2015)8 (Data Citation 3). Briefly, after prefiltration through 3.0 μm, DNA was extracted from 0.2 μm Sterivex™ cartridge filters (Millipore) using the protocol described in Riemann et al. (2000)21 and sequenced on one HiSeq high-output flowcell with an average of 31.9 million pair-end reads per sample.

The 30 transect samples were taken during a cruise initiated by Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research, Warnemünde on the R/V Alkor, carried out for the BONUS BLUEPRINT project from June 4 to June 17 2014. Samples for DNA analyses were collected using a compact CTD (profiling instrument that records conductivity, oxygen, temperature and depth) SBE 911 Plus with a SBE-rosette SBE32 (Sea Bird Electronics Inc., USA) equipped with 18×10 L FreeFlow-PWS-samplers (HYDRO-BIOS, Kiel, Germany). Water was sampled from oxic zones, in the range from 2 to 242 m depth, within the salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. For DNA analysis, 1 L of seawater was directly filtered onto a 47 mm Durapore membrane filter with 0.2 μm pore size (GVWP04700, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) by a vacuum of <300 mbar. Subsequently, the filters were folded, flash frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further processing. DNA was extracted using a modified protocol of the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (51304, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with an initial bead-beating step and a cleanup and concentration process using the Zymo gDNA Clean and Concentrator Kit (D4010, Zymo Research Europe, Freiburg, Germany). The concentration and quality of the eluted DNA was assured by gel electrophoresis and Bioanalyzer DNA 12000 kit (5067-1508, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). The samples were sequenced at the National Genomics Infrastructure at Science for Life Laboratory, Stockholm, Sweden, using a full HiSeq 2500 high-output flowcell producing an average of 69.5 million pair-end reads per sample.

The redoxcline samples consist of samples from station Boknis Eck (Data Citation 4), located at the entrance of the Eckernforde Bay in the southwestern Baltic Sea, and from station TF0271 at the Gotland Deep in the eastern Gotland Basin. The Boknis Eck station was sampled on September 23, 2014 on the R/V Littorina during routine monitoring activities performed monthly by the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel. Due to windy conditions before the sampling day, the water at the Boknis Eck station was mixed over most of the water column and only the bottom water was sulfidic. Water was sampled from the mixed oxygenated layer and from the sulfidic bottom water, which was captured on a 3 μm pore size membrane filters (Whatman, Maidstone, UK) followed by 0.2 μm pore size Sterivex-GV filters (Millipore Billerica, Massachusetts, USA). The Gotland Basin was sampled during the cruise EMB087 on the R/V Elisabeth Mann Borgese on October 18 and October 26, 2014. The samples from October 18 were taken in the context of an experiment close to the oxic-anoxic interface from suboxic and anoxic water layers and were captured directly on 0.2 μm pore size Durapore membrane filters (Whatman, Maidstone, UK). The samples from October 26 were taken to cover different zones in the redox gradient (suboxic, oxic-anoxic interface, upper sulfidic, lower sulfidic) and were captured first on a 3 μm pore size membrane filters (Whatman, Maidstone, UK) followed by 0.2 μm pore size Sterivex-GV filters. DNA from water captured on 3 μm pore size membrane filters and 0.2 μm Sterivex-GV filters was extracted using the QIAmp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany): ATL buffer was added to filter pieces together with 200 μm low-binding Zirconium beads (OPS Diagnostics, Lebanon, NY, USA) and the suspension was vortexed for 5 minutes at maximum speed. Subsequently proteinase K was added and the suspension was incubated for approximately 1h at 56 °C before continuing DNA extraction by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleic acids from Gotland Basin water sampled on October 18 on 0.2 μm pore size membrane filters were extracted using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Similar as before, filters were vortexed together with Zirconium beads in RTL buffer before continuing nucleic acid extraction by following the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration and quality of the eluted DNA was assured by gel electrophoresis. The samples were sequenced on a single HiSeq 2500 lane producing an average of 20.7 million pair-end reads per sample.

All sequencing libraries (including LMO) were prepared with the Rubicon ThruPlex kit (Rubicon Genomics, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Preprocessing and Assembly

The quality of the reads were checked and visualized with FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) through MultiQC22 and trimmed from low quality bases with cutadapt23 using Phred score 15 as a cutoff. Adapter sequences were also removed using cutadapt, keeping only read pairs where both reads in the pair were longer than 31 bases. Preprocessed reads were then assembled using Megahit24 version 1.0.2 with default parameters including kmers 21,41,61,81 and 99.

Exclusively to the 30 samples from the transect cruise, genomic material (20 ng per L of seawater) from a known genome of Thermus thermophilus (strain HB8), which is not expected to be present in the Baltic Sea naturally, was added after filtration but prior to the DNA extraction, serving as internal standard to enable absolute quantifications. Aligning all contigs from the metagenome assembly against this reference genome showed that 84.1% of the genome was recovered within contigs aligning with average 99.82% identity. These additional genome contigs were kept in the reference assembly but reads aligning to the reference genome were filtered out before the quantification steps, and before uploading the processed reads to the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (Data Citation 5).

Functional Annotation

Genes were predicted on all contigs using Prodigal25 version 2.6.3 with the ‘--meta’ tag which potentially uses different coding tables for different contigs. Genes located on contigs longer or equal to 1 kilobase, identified with the script toolbox/scripts/fasta_lengths.py, were used for functional and taxonomic annotation. For functional annotation, the databases EggNOG17, Pfam16, TIGRFAM (http://www.jcvi.org/cgi-bin/tigrfams/index.cgi) and dbCAN18 were chosen. Furthermore, EC-numbers19 were extracted from the EggNOG annotations.

To annotate genes with EggNOG17 IDs, the EggNOG hmm file for all organisms, NOG.hmm.tar.gz, version 4.5 was downloaded from http://eggnogdb.embl.de/download/eggnog_4.5/data/NOG/. For performance reasons, hmmsearch was used instead of hmmscan26, initially removing all hits with an E-value >0.0001. To select a maximum of one annotation per gene, the hit with highest score was chosen using the script toolbox/scripts/hmmer_filtering/keep_top_score.py. Information about each annotation was downloaded from http://eggnogdb.embl.de/download/eggnog_4.5/data/NOG/NOG.annotations.tsv.gz.

An Enzyme Commision (EC) number19 was assigned to each EggNOG through the Uniprot27 proteins included in the EggNOG model, if a majority of its EC-assigned members were assigned to that EC. Note that proteins could have multiple EC numbers assigned and therefore some EggNOGs were assigned multiple EC numbers. The files needed for the conversion were eggnog4.protein_id_conversion.tsv.gz (downloaded from http://eggnogdb.embl.de/download/eggnog_4.5/ on January 9th 2017) and NOG.members.tsv.gz (downloaded from http://eggnogdb.embl.de/download/eggnog_4.5/data/NOG/ on January 9th 2017). The protein ID conversion file gives EC numbers per reference protein and the members file gives the reference proteins that build each model. The protein with taxaid 400682 and protein ID “PAC” was removed from the protein ID conversion file since it had 695 EC entries. Likewise for taxaid 7070 and protein ID “TCOGS2”, with 686 EC entries. The protein ID with the third most entries had 6 entries and therefore the two others were deemed as outliers. The suspected reason is that these entries belong to different genes for these genomes but there were no way to resolve this and the EC-number assignment for each EggNOG was deemed to not be affected by this. Given the assignment of EC-numbers per EggNOG, the assignment per gene was done with toolbox/scripts/assign_ec_from_nog.py.

Annotation against the dbCAN18 (DataBase for automated Carbohydrate-active enzyme ANnotation) database was performed using version 5 (downloaded from http://csbl.bmb.uga.edu/dbCAN/download.php). Following the instructions from dbCAN (downloaded from http://csbl.bmb.uga.edu/dbCAN/download/readme.txt), hmmscan26 was used with the option --domtblout and the result was further treated with the recommended script hmmscan-parser.sh (reference of used script available within toolbox/third_party_scripts/dbcan/hmmscan-parser.sh) from dbCAN requiring a covered fraction of the HMM larger than 0.3 and keeping long alignments (>80 amino acids) if the E-value was less than 1e-5 and short alignments if the E-value was less than 1e-3. An additional script toolbox/hmmer_filtering/dbcan_strict_filtering.py was applied, choosing to follow recommendations for bacteria from dbCAN, keeping annotations with e-value less than 1e-18 and alignment coverage greater than 0.35. To allow for more than a single domain within a gene, any annotation which fulfilled these criteria was kept. Information about each annotation was collected (downloaded from http://csbl.bmb.uga.edu/dbCAN/download/FamInfo.txt).

Annotation against Pfam16 version 30.0 was conducted with the script pfam_scan.pl supplied from the ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/Pfam/Tools for version 28.0, using hmmer version 3.1b1 (ref. 26). To allow for more than a single domain within a gene, any annotation which fulfilled these criteria was kept. Information about each annotation was collected as columns 1,2 and 4 from the file pfamA.txt.gz downloaded from ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/Pfam/releases/Pfam30.0/database_files/ on January 11th 2017.

Annotation against TIGRFAM version 15, was performed using hmmsearch (v. 3.1b2)26 with --cut_tc argument to filter models by trusted cutoff. For each protein sequence, the best scoring HMM was selected using hmmparse.py available at https://github.com/johnne/biotools/blob/master/scripts/hmmparse.py

Taxonomic annotation

The method used to assign taxonomy was chosen in order to assign as many contigs as possible to a taxonomy while still keeping false positives to a low level. As the number of sequences in reference databases closely related to the genomes in our samples was expected to be low8, amino acid sequences from the assembly were used to compare against other amino acid sequences in the reference database, enabling higher sensitivity (due to the more conserved nature of amino acid sequences). This comparison was done using Diamond version 0.8.26 (ref. 28) with the parameters “--seg yes”,”--sensitive” and “--top 10” against the NCBI nr database downloaded December 2nd 2016.

The code used to assign taxonomy from the Diamond search was based on an original available in the DESMAN package29 and the modified version of the code is available as the script toolbox/scripts/taxonomy_from_genes_to_contigs/lca_per_contig.py. The assignment was done as follows: all reported hits from the Diamond search were given a weight based on the aligned fraction of the query and the percentage identity of the alignment. At each taxonomic level, if the sum of the weights for one taxon was greater than half the sum of all weights, the gene was assigned to that taxon as long as the percentage identity was high enough. The levels for the percentage identity were set to 40% at superkingdom level, 50% at phylum level, 60% at class level, 70% at order level, 80% at family level, 90% at genus level and 95% at species level.

Taxonomic assignments were set per contig to the most detailed level where consensus for at least 50% of the weights of the preliminary gene assignments could be achieved. Genes without taxonomic annotation were ignored. The shared assignment was propagated to all genes present on that contig. In this way, all genes present on one contig will always share the taxonomic assignment. If no single superkingdom accounted for a majority of the gene assignment weights for a contig, the contig was left unassigned.

Quantification and Normalization

To use the metagenome assembly as a reference assembly, individual samples are functionally and taxonomically annotated by quantifying the different annotations present in the assembly. This is done by mapping all short reads against the assembly and quantifying genes, and thereby any associated annotation, with the number of reads mapping to them. More specifically bowtie2 (ref. 30) version 2.2.6 was used with the parameter “--local” for mapping, duplicated reads were removed with picard version 1.118, bam-file sorting was done with Samtools31 version 1.3, and the htseq-count script from htseq32 version 0.6.1 was used to get raw counts per gene. Counts per annotation was achieved by summing all counts for genes annotated with each respective annotation.

When quantifying annotation types where multiple annotations were allowed for a single gene (dbCAN and Pfam), some genes contributed several times to the quantities. This was kept in order to facilitate analysis of differential abundance for the individual annotations.

Along with raw counts of reads for each annotation type and taxonomy, a count normalized by gene length and number of mapped reads was also calculated. Analogously to the formula for Transcripts Per Million used in transcriptomics (ref 33), we calculate TPM for gene counts:

Where rg is the number of reads mapped to gene g from the sample, rl is the average read length for the sample, flgis the length of the gene and G is the set of all genes. T is a convenience variable for the indicated sum over all genes.

Code availability

Code used to preprocess reads, assemble contigs and annotate genes is publicly available at https://github.com/EnvGen/BLUEPRINT_pipeline, containing the pipeline definition of the workflows used, https://github.com/EnvGen/snakemake-workflows, where the snakemake rules are specified in order to build the command used for each step, and the branch BARM_publication of https://github.com/EnvGen/toolbox, for custom scripts. Scripts within the latter repository that have been used have been indicated throughout the text.

Data Records

The preprocessed sequencing reads from the Transect and Redoxcline samples were submitted to ENA hosted by EMBL-EBI under the study accession number PRJEB22997 (Data Citation 5). The raw reads from LMO were published elsewhere8 and are accessible at NCBI (Data Citation 3). Contig, gene and protein sequences from the co-assembly of the Transect, Redoxcline and LMO samples, as well as quantification tables, contextual data for the samples, and the annotations for each gene are accessible on Figshare (Data Citation 1). The raw sequencing reads from the external samples used for evaluation were also published elsewhere34 and are accessible at NCBI (Data Citation 2).

Technical Validation

The mapping rates for all samples included in the reference assembly are shown in Fig. 2, where the majority of samples included in the assembly reaches a level above 80%. This serves as a validation of the completeness of the metagenome assembly. The fraction of reads that did not map to the coassembly, and were hence not assembled past the 200 bases length cutoff most likely originate from low abundance species, or species with high intraspecies diversity generating fragmented assemblies. The mapping rate of the external samples shows the capability for this assembly to serve as a reference metagenome assembly for the Baltic Sea. These external samples34 were collected in a different year (2011) and a station (58.82 N 17.63 E) separate from where the samples included in the assembly were taken. This represents a realistic scenario where BARM is used as a reference metagenome for the Baltic Sea. The mapping rates vary with the filter fractions, where reads originating from the largest (3.0–200 μm) and smallest (<0.1 μm) fractions displayed lower rates than the two intermediate fractions (0.1–0.8 μm and 0.8–3.0 μm), indicating that picoplankton are better represented in BARM than larger eukaryotic plankton and viruses.

Assignment rates for different annotation types, as shown in Fig. 3, are in the majority of cases below 10% of the total number of reads, which is expected since only genes on long contigs (representing 40% of the bases of the total assembly) were predicted and subjected to annotation. The fraction of reads annotated among reads mapping to genes included in the annotation procedure reaches well over 30% for Pfam and shows the generality of that database as compared to i.e. dbCAN, a much more niched resource, which reaches only around 2% of reads mapping to genes included in the annotation.

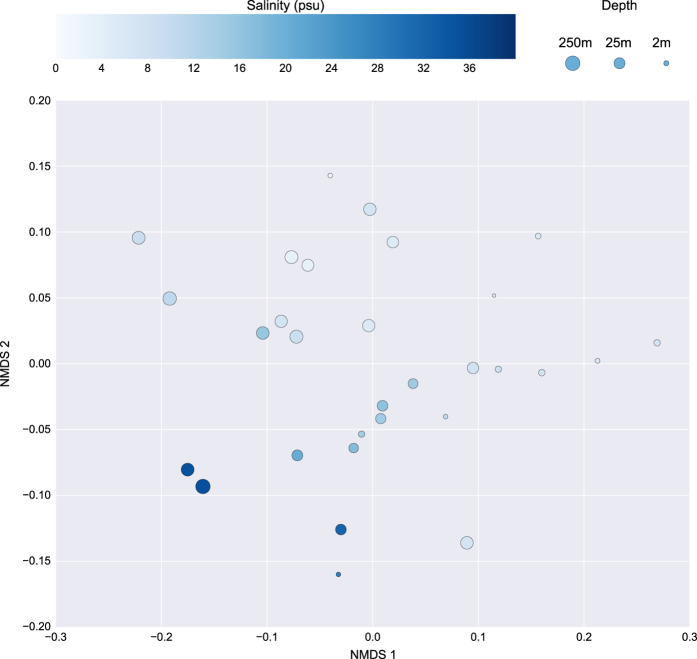

The functional annotation was further validated through an NMDS plot (Fig. 4) based on the EggNOG annotations of the transect data. Depth was found to be negatively correlated with the first dimension (Spearman’s rank correlation ρ=−0.73, P=5.4−06) and salinity was negatively correlated with the second dimension (Spearman’s rank correlation ρ=−0.77, P=2.4−06). These two environmental parameters have previously been found to correlate strongly with the microbial community in the Baltic Sea5 which strengthens our trust in the EggNOG annotations. Furthermore, analyzing a single annotation with a known function, namely the photosynthetic reaction centre protein (PF00124), we could see a strong negative correlation with sampling depth over the thirty transect samples (Spearman correlation coefficient ρ=−0.87, P=3.1-10).

Figure 4. Non-metric dimensional scaling (NMDS) of the 30 samples included in the Transect sample group based on EggNOG annotation.

Samples are colored and sized according to salinity and depth, respectively. Created using Matplotlib39 and Seaborn40.

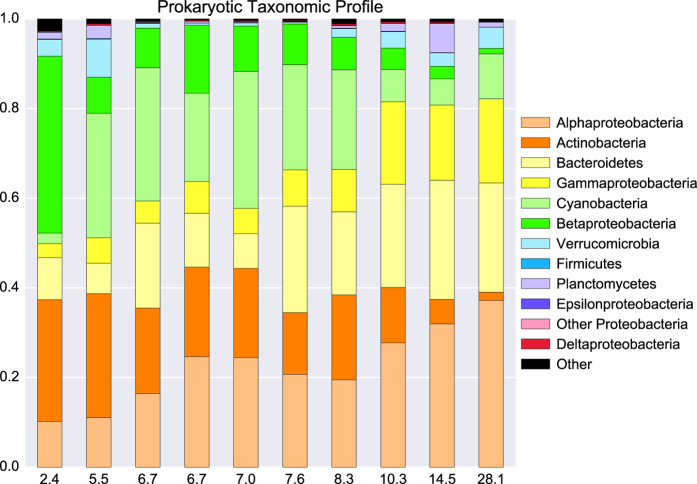

The taxonomic annotation was validated by inspecting the taxonomic profile of the transect samples. The same dominant prokaryotic taxonomic groups were observed as in previous pan-Baltic amplicon sequencing and metagenomic studies5,7,10,11, and the overall trends were conserved with an increase in Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria and a decrease in Actinobacteria and Betaproteobacteria with increasing salinity levels (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Taxonomic profiles of the 10 transect samples obtained from surface waters.

Numbers on x-axis indicate salinity, given in practical salinity units (PSU), and are sorted with increasing salinity to the right. Created using Matplotlib39 and Seaborn40.

Among the predicted proteins in BARM, 98% lacked hits with amino acid identities above 95%, hence potentially representing species for which sequenced genomes are lacking35. 31% of the sequences lacked significant hits (E-value >1) and potentially correspond to novel protein families.

Usage Notes

A publicly available repository at https://github.com/EnvGen/BARM_tools hosts instructions and a pipeline on how to quantify genes and their annotations within BARM for any kind of Baltic Sea metagenomic and metatranscriptomic samples.

The web interface BalticMicrobeDB, available to the public at http://barm.scilifelab.se, can be used to explore and access data for the three sample sets that the assembly is based upon. At the index page, the user can choose whether to access functional annotations or taxonomic annotations. For the functional annotations, the user can select specific annotation sources and identifiers and select the sample groups for which the counts will be displayed. Furthermore, a text search over the identifiers and the descriptions of the annotations can be used to create a custom table of counts over the selected samples. For taxonomic annotations, counts for the top level superkingdom are first presented but the user can unfold a taxonomic tree to select any taxon to view counts for.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Alneberg, J. et al. BARM and BalticMicrobeDB, a reference metagenome and interface to meta-omic data for the Baltic Sea. Sci. Data 5:180146 doi: 10.1084/sdata.2018.146 (2018).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work resulted from the BONUS Blueprint project supported by BONUS (Art 185), funded jointly by the EU and the Swedish Research Council FORMAS, The Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), Estonian Research Council, and Danish Council for Independent Research. It was also funded by the Swedish Research Council VR (grant 2011-5689) through a grant to A.F.A. Computations were performed on resources provided by the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) through the Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science (UPPMAX). DNA sequencing was conducted at the Swedish National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI) at Science for Life Laboratory (SciLifeLab) in Stockholm. The Redoxcline samples were made possible through generous support from the Boknis Eck coastal time series station (http://www.bokniseck.de) run by the Chemical Oceanography Research Unit at GEOMAR.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Citations

- Alneberg J., Andersson A. F. 2018. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.3831631

- 2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP077551

- 2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP058493

- Bange H. W., Malien F. 2015. PANGAEA. https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.855693

- 2017. European Nucleotide Archive. ERP104730

References

- Snoeijs-Leijonmalm P. & Andrén E. in Biological Oceanography of the Baltic Sea 23–84 (Springer: Dordrecht, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Blenckner T., Österblom H., Larsson P., Andersson A. & Elmgren R. Baltic Sea ecosystem-based management under climate change: Synthesis and future challenges. Ambio 44(Suppl 3): 507–515 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann L. et al. The native bacterioplankton community in the central Baltic Sea is influenced by freshwater bacterial species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 503–515 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson A. F., Riemann L. & Bertilsson S. Pyrosequencing reveals contrasting seasonal dynamics of taxa within Baltic Sea bacterioplankton communities. ISME J. 4, 171–181 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlemann D. P. et al. Transitions in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. ISME J. 5, 1571–1579 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thureborn P. et al. A metagenomics transect into the deepest point of the Baltic Sea reveals clear stratification of microbial functional capacities. PLoS ONE 8, e74983 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont C. L. et al. Functional tradeoffs underpin salinity-driven divergence in microbial community composition. PLoS ONE 9, e89549 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugerth L. W. et al. Metagenome-assembled genomes uncover a global brackish microbiome. Genome Biol. 16, 279 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindh M. V. et al. Disentangling seasonal bacterioplankton population dynamics by high-frequency sampling. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 2459–2476 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y. O. O., Karlson B., Charvet S. & Andersson A. F. Diversity of Pico- to Mesoplankton along the 2000 km Salinity Gradient of the Baltic Sea. Front. Microbiol 7, 679 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlemann D. P. R., Lundin D., Andersson A. F., Labrenz M. & Jürgens K. Phylogenetic Signals of Salinity and Season in Bacterial Community Composition Across the Salinity Gradient of the Baltic Sea. Front. Microbiol 7, 1883 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzi Y., Falony G., Vieira-Silva S. & Raes J. Towards biome-specific analysis of meta-omics data. ISME J. 10, 1025–1028 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207–214 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. et al. An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 834–841 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunagawa S. et al. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 348, 1261359 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D. et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D279–D285 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Cepas J. et al. EGGNOG 4.5: A hierarchical orthology framework with improved functional annotations for eukaryotic, prokaryotic and viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D286–D293 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y. et al. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W445–W451 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb E. C. Others. Enzyme nomenclature 1992. Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enzymes (Academic Press, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Asplund-Samuelsson J. et al. Diversity and Expression of Bacterial Metacaspases in an Aquatic Ecosystem. Front. Microbiol 7, 1043 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann L., Steward G. F. & Azam F. Dynamics of bacterial community composition and activity during a mesocosm diatom bloom. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 578–587 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewels P., Magnusson M., Lundin S. & Käller M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 17, 10–12 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Liu C.-M., Luo R., Sadakane K. & Lam T.-W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 119 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy S. R. Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D204–D212 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B., Xie C. & Huson D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quince C. et al. DESMAN: a new tool for de novo extraction of strains from metagenomes. Genome Biol. 18, 181 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B. & Salzberg S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P. T. & Huber W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G. P., Kin K. & Lynch V. J. Measurement of mRNA abundance using RNA-seq data: RPKM measure is inconsistent among samples. Theory Biosci 131, 281–285 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson J. et al. Picocyanobacteria containing a novel pigment gene cluster dominate the brackish water Baltic Sea. ISME J. 8, 1892–1903 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis K. T. & Tiedje J. M. Towards a genome-based taxonomy for prokaryotes. J. Bacteriol. 187, 6258–6264 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pante E. & Simon-Bouhet B. marmap: A package for importing, plotting and analyzing bathymetric and topographic data in R. PLoS ONE 8, e73051 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The R Core-team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Amante C. & Eakins B. W. ETOPO1 1 arc-minute global relief model: procedures, data sources and analysis (US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service, National Geophysical Data Center, Marine Geology and Geophysics Division Colorado, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Waskom M. et al. seaborn v0. 7.0. Zenodo, doi 10 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Alneberg J., Andersson A. F. 2018. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.3831631

- 2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP077551

- 2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP058493

- Bange H. W., Malien F. 2015. PANGAEA. https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.855693

- 2017. European Nucleotide Archive. ERP104730