This consortia-based evaluation and replication study shows that higher inflammatory potential of diet and non-O blood type are each associated with increased risk for PC, but the two exposures do not interact to influence PC risk.

Abstract

Diets with high inflammatory potential are suspected to increase risk for pancreatic cancer (PC). Using pooled analyses, we examined whether this association applies to populations from different geographic regions and population subgroups with varying risks for PC, including variation in ABO blood type. Data from six case–control studies (cases, n = 2414; controls, n = 4528) in the Pancreatic Cancer Case–Control Consortium (PanC4) were analyzed, followed by replication in five nested case–control studies (cases, n = 1268; controls, n = 4215) from the Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium (PanScan). Two polymorphisms in the ABO locus (rs505922 and rs8176746) were used to infer participants’ blood types. Dietary questionnaire-derived nutrient/food intake was used to compute energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index (E-DII®) scores to assess inflammatory potential of diet. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using multivariable-adjusted logistic regression. Higher E-DII scores, reflecting greater inflammatory potential of diet, were associated with increased PC risk in PanC4 [ORQ5 versus Q1=2.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.85–2.61, Ptrend < 0.0001; ORcontinuous = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.17–1.24], and PanScan (ORQ5 versus Q1 = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.92–1.66, Ptrend = 0.008; ORcontinuous = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.02–1.15). As expected, genotype-derived non-O blood type was associated with increased PC risk in both the PanC4 and PanScan studies. Stratified analyses of associations between E-DII quintiles and PC by genotype-derived ABO blood type did not show interaction by blood type (Pinteraction = 0.10 in PanC4 and Pinteraction=0.13 in PanScan). The results show that consuming a pro-inflammatory diet and carrying non-O blood type are each individually, but not interactively, associated with increased PC risk.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a major cause of cancer-related death in developed countries (1,2). In the United States, PC has surpassed breast cancer to become the fourth leading cause of cancer death in men and women combined, with a 5-year survival of only 8% (3). Established risk factors for PC include a positive family history of PC, cigarette smoking, pre-existing diabetes mellitus, non-O ABO blood type, chronic pancreatitis and obesity (2,4,5). Because of the extremely poor prognosis of PC, identifying additional modifiable risk factors for PC is crucial for prevention efforts (2). Epidemiological studies suggest that diet plays a plausible role in PC development (6,7). However, the association between dietary habits and PC is unclear, partly because diet is a complex exposure and its impact is probably most relevant a decade or more before PC diagnosis. Additionally, the assessment of individual dietary components or single nutrients in relation to PC risk, which has yielded mixed results (7–10), does not reflect the overall quality of a person’s diet; the absence of this information could obscure important clues about the role of whole diet on PC risk.

Approaches that assess the whole diet have the potential to take into account interactions between dietary components and can provide insight into whether certain food patterns foster favorable or deleterious changes in the intermediate pathway(s) of a disease process (11). On this premise, the dietary inflammatory index (DII®) was developed and construct-validated as a tool to assess inflammatory potential of the diet (12,13). The DII scores up to 45 dietary components based on evidence from published literature showing whether each component increases, decreases or has no relationship to the following circulating inflammatory biomarkers: interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and C-reactive protein (12). The inflammatory potential of a person’s diet is determined by summing inflammatory index scores across the dietary components. Based on the DII, two previous studies reported increased PC risk for individuals with greater dietary inflammatory potential (14,15); however, questions remain as to the validity and consistency of the association, and applicability of the findings to populations from different geographic regions and population subgroups with varying environmental and genetic risks for PC.

ABO blood type is an established genetic risk factor for PC, and is determined by the ABO gene, located on chromosome 9q34.1 (5,16–18). ABO encodes glycosyltransferase enzymes that catalyze the attachment of specific carbohydrate molecules to the H antigen (19). The association of ABO blood type with PC risk was first reported in 1960, with nearly consistent results from studies published since then (18). Individuals with type O blood have a lower risk of developing PC than those with blood types A, B or AB (18). Variation in ABO blood type has been associated also with varying levels of circulating inflammatory markers (e.g. intercellular adhesion molecule-1, E-selectin and TNF-a) (20–23), suggesting that inflammation may link ABO blood type to PC risk. It is therefore plausible that ABO blood type might act in concert with modifiable inflammation modulators, such as cigarette smoking or pro-inflammatory diet, to increase PC risk further.

The primary aim of this study was to examine the association between dietary inflammatory potential, as measured by the DII, and PC risk in a large, multicenter, pooled analysis of individual-level data from six studies in the Pancreatic Cancer Case–Control Consortium (PanC4), followed by replication of findings in five nested case–control studies from the Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium (PanScan). The secondary aim was to investigate whether an association between a pro-inflammatory dietary pattern and PC is modulated by known risk factors of PC, including ABO blood type and cigarette smoking. All initial analyses were performed using data from the retrospective case–control studies in PanC4, followed by replication using data from the prospective cohorts in PanScan.

Materials and methods

For the initial analyses, data on 2450 individuals with incident PC (cases) and 4562 non-cancer controls were obtained directly from PanC4 investigators at Mayo Clinic (14), University of Minnesota (UMN) (24), MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) (25), University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) (26), Yale University (16) and Milan and Pordenone provinces in Italy (27). The cases and controls were obtained through collaboration in PanC4 (28,29). The data from the PanC4 studies were combined into a single dataset following a standardized process for data harmonization (29). For the replication analyses, we obtained prospectively collected dietary data and covariates on 1271 incident PC cases matched to 4249 controls by PanScan investigators (28,30,31) from the following studies: Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial (32); Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene (ATBC) Cancer Prevention Trial (33); New York University Women’s Health Study (NYU-WHS) (34); European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) (35); and Shanghai Men’s and Women’s Health Study (SMWHS) (36). At a minimum, all of the PanScan studies matched controls to cases based on year of birth (in 5-year groups), sex and self-reported race/ethnicity. Some performed more robust matching for age, such as age at baseline or age at blood draw (5-year age groups) and/or additional matching for smoking, date or time of day of fasting blood draw and years of follow-up (37). Data from the PanScan studies also were harmonized following a standardized protocol (37) and combined into a single data set for analysis. Detailed descriptions of each study, including recruitment periods, recruitment methods and design are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online. Structured questionnaires were administered in each study to collect health-related information that included demographics, personal and family health history, smoking history and anthropometry. Summaries of the data obtained from each study are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, available at Carcinogenesis Online. All participating studies previously received ethics approval from their respective Institutional Review Board (IRB). Additional approval was obtained from the Mayo Clinic IRB for the pooled analyses.

Data received from the PanC4 studies included information on age at diagnosis or recruitment (controls); sex; race/ethnicity; usual adult weight and height; smoking status (never, former, current and number of cigarettes smoked per day, and smoking duration for former and current smokers); personal history of diabetes (yes, no); and first-degree family history of PC (yes/no). For this study, participants who reported smoking <100 cigarettes in their lifetime were considered non-smokers. Pack-years of smoking were calculated by multiplying the number of packs smoked per day (20 cigarettes per pack) by the number of years of smoking. Usual adult height and weight were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2. One of the PanC4 studies (UMN) did not have information on height or weight; therefore, we created a separate category for participants with missing information on BMI, and BMI was categorized as <25, 25–29, ≥30 kg/m2 and unknown. Data obtained from the PanScan studies included previously harmonized data on age and date of PC diagnosis for cases, BMI, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, personal history of diabetes and first-degree family history of PC. The data were categorized similarly for the PanC4 and the PanScan studies for analyses (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Assessment of ABO blood type

One tag single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, rs505922) and one functional SNP (rs8176746) in the ABO locus were used to infer participants’ blood types. Four of the PanC4 studies (Mayo, MDACC, UCSF and Yale) had the genotype data required to identify ABO blood type, and while all five PanScan studies had genotype data, not all individuals in the studies had the ABO SNP data (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, available at Carcinogenesis Online). All participants who had ABO SNP data were genotyped in either the PanScan I or PanScan II GWAS (28,30) or the PanC4 GWAS (38). The genotyping methods and quality control measures have been published (28,30,38). The T allele of rs505922 tags the O blood type, while the A allele of rs8176746 determines the B blood type, and a haplotype of the two SNPs identifies the A blood type (39). Thus, participants who carry both the TT genotype of rs505922 and the CC genotype of rs8176746 were coded as having type O blood, and all others were coded as having a non-O blood type, as has been done previously (17,18,39).

Dietary assessment

Diet was assessed in each study with validated food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) (14,16,24–27,32,34–36) or diet history questionnaires (DHQ) (33). All of the dietary instruments used in the participating studies were designed to measure usual dietary habits; however, the periods of diet assessment differed among studies, particularly among the PanC4 studies (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Three of the PanC4 studies (UMN, MDACC and UCSF) adapted the Willett FFQ (40), which asked participants to recall their dietary intake in the 12 months prior to diagnosis or recruitment (controls) and included questions about usual frequency of intake. In the UMN study, the Willett FFQ was modified slightly to include foods common in the upper Midwestern region of the United States (24). The FFQ used in the Italian study asked about dietary habits in the 2 years prior to diagnosis or recruitment and included questions on usual frequency and usual portion size (27). In the Mayo and Yale studies, cases and controls were asked to recall their usual dietary intake in the previous 5 years or during the previous 1–5 years, respectively. In the Mayo study, there was an additional question asking if participants had changed their diet in the last 5 years; those who indicated they had changed their diet were excluded from the analyses. Both the Mayo and Yale studies included questions on intake frequency but did not ask about portion size; thus, portion size was assumed to be medium intake for all items. The dietary instruments used in the PanScan studies asked participants to recall intake in the 12 months prior to enrollment and asked about usual portion size and frequency of intake. Some of the PanScan studies collected additional follow-up dietary information; however, only the baseline dietary data were used in this study. In both PanC4 and PanScan, participants’ usual nutrient intake from various foods was estimated in each study by linking the FFQ or DHQ responses to regionally appropriate nutrient databases. Dietary supplement use was not assessed in the present analysis.

Calculation of the E-DII Score

Food and nutrient estimates obtained from the dietary questionnaires were used to calculate energy-adjusted DII (E-DII) scores (41). In brief, the DII classifies an individual’s diet from the extremes of anti-inflammatory to pro-inflammatory, with the ability to adapt to various populations across the globe. The DII scores are based on information derived from a review of 1943 studies published between 1950 and 2010, which assessed the associations of various dietary factors on six commonly studied inflammatory biomarkers: IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-1, TNF-α and C-reactive protein. Scores were assigned to each DII component (i.e. food parameter) based on the overall evidence from the publications indicating whether that food parameter increased (+1), decreased (−1) or had no effect (0) on the six inflammatory biomarkers. In total, 45 food parameters that included various micro- and macronutrients and whole foods were identified in the search and scored (41). After weighting by study design, adjusting for the size of the literature pool, and calculating z scores for intake of the food parameters compared with mean energy-adjusted global intakes (based on standard intake of 1000 kcal), all food parameter-specific DII scores were summed to derive an overall E-DII score for each participant, with higher E-DII scores reflecting a more pro-inflammatory diet (42).

Among the PanC4 studies, UMN had the largest number of food parameters (n = 30) used for calculating the E-DII and Yale had the least number (n = 18) (Supplementary Table 5, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Altogether, the PanC4 studies provided 35 unique food parameters out of the 45 parameters included in the development of the DII. Of the 35 unique food parameters derived from FFQs used in the PanC4 studies, nine were pro-inflammatory and were assigned positive inflammatory scores based on the E-DII scoring algorithm (carbohydrate, cholesterol, energy [calories], iron, protein, saturated fat, total fat, trans fat and vitamin B12); 26 were assigned negative inflammatory scores (alcohol, anthocyanidins, β-carotene, caffeine, fiber, flavan-3-ol, flavones, flavonol, flavonones, isoflavones, magnesium, monounsaturated fatty acids, niacin, omega 3 fatty acids, omega 6 fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, riboflavin, selenium, tea, thiamin, vitamins A, B6, C, D and E and zinc). For the PanScan studies, EPIC’s FFQ had the largest number of food parameters (n = 36) available for calculation of the E-DII, while NYU-WHS had the fewest (n = 19) (Supplementary Table 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Of thirty-nine unique food parameters derived from the dietary questionnaires used in the PanScan studies, nine were assigned positive inflammatory scores (carbohydrate, cholesterol, energy, iron, protein, saturated fat, total fat, trans fat and vitamin B12), and 30 were assigned negative inflammatory scores (alcohol, anthocyanidins, b-carotene, caffeine, fiber, flavan-3-ol, flavones, flavonol, flavanone, folate, folic acid, garlic, isoflavones, magnesium, monounsaturated fatty acids, niacin, omega 3 fatty acid, omega 6 fatty acid, onions, polyunsaturated fatty acids, riboflavin, selenium, tea, thiamin, vitamins A, B6, C, D, and E and zinc).

Exclusions

From the 2450 PC cases and 4562 controls in the PanC4 studies, we excluded participants whose FFQ responses resulted in implausible values for energy intake (<500 or >6000 kcal/day for men, 22 cases and 19 controls; <600 or >5000 kcal/day for women, 14 cases and 15 controls), leaving 2414 cases and 4528 controls for the PanC4 analyses. From the 1271 PC cases and 4249 controls in PanScan, we excluded individuals with implausibly high or low levels of energy intake (men, 2 cases and 29 controls; women, 1 case and 5 controls), leaving 1268 cases and 4215 controls for the PanScan analyses. Further details are provided in Supplementary Tables 7 and 8, available at Carcinogenesis Online.

Statistical analysis

Initial analyses were performed using the PanC4 studies, followed by replication analysis using the PanScan studies. For both PanC4 and PanScan, means and proportions were used to compare cases and controls on demographic, lifestyle and clinical characteristics. Unconditional logistic regression was used to calculate study-specific and pooled odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% CIs. The pooled analyses were performed by combining individual-level data from each study into a single, harmonized dataset. Before performing pooled analyses, we examined between-study heterogeneity using likelihood ratio Χ2 statistics between logistic regression models with and without multiplicative interaction terms. We first examined the association between ABO blood type and PC risk in each study by comparing participants with non-O blood type to those with type O blood (referent group). The following pre-determined risk factors of PC were included in the model: age (continuous), sex, race (White, other), self -reported history of diabetes (yes, no), first-degree family history of PC (yes, no), BMI (< 25, 25–29, ≥30 kg/m2, unknown) and pack-years of smoking within smoking category (never, former with <15 pack-years, former with ≥15 pack-years, current with <15 pack-years, current with ≥15 pack-years). All participants in the ATBC trial were current smokers and all had data on pack-years of smoking; thus, smoking was categorized as current with <15 pack-years versus current with ≥15 for this study. In addition to the covariates listed above, additional adjustment for study site was performed in the pooled analyses for the PanC4 and PanScan studies, separately. Results were plotted for visual comparison among studies.

The association between E-DII scores and PC risk was examined in two ways. First, the E-DII scores were modeled as a continuous variable for study-specific and pooled analyses, and results were plotted for visual comparison. We then categorized the E-DII scores into quintiles based on sex-specific control distribution categorized separately in each study. The sex- and study-specific quintiles were then pooled from each study into a single data set for the pooled analyses. In modeling the E-DII quintiles, we used the lowest quintile as the referent group to estimate ORs and 95% CIs for the higher quintiles. All E-DII association analyses were adjusted for the above-listed risk factors, with additional adjustment for study site in the pooled analyses. We also examined whether the association between E-DII quintiles and PC was homogenous across strata of selected risk factors of PC: smoking status (never, former, current), ABO blood type (O, non-O), age (< 65, ≥65 years), sex, race (White, other), BMI (<25, ≥25 kg/m2, unknown), personal history of diabetes (yes, no) and first-degree family history of PC (yes, no). We examined also interaction between the E-DII and these risk factors (e.g. continuous E-DII variable [or E-DII quintile] by age group) using likelihood ratio Χ2-tests. Further, we adjusted for pack-years of smoking (continuous) among former and current smokers in the stratified analysis by smoking status.

Results

Characteristics of the incident PC cases and controls included in the analyses are presented in Tables 1 and 2 for the six PanC4 and the five PanScan studies, respectively. The 2414 cases and 4528 controls in the PanC4 studies were roughly similar in distributions of age, sex and race, but the cases were more frequently obese than the controls (BMI ≥30 kg/m2, 22% versus 18%) (Table 1). Higher proportions of current smokers and individuals with personal histories of diabetes or first-degree family histories of PC were noted for cases compared with controls. In the PanScan studies, the 1268 cases were, on average, older than the 4215 controls (67 versus 63 years, respectively) at baseline (Table 2). The cases had also higher percentages of women, racial minorities, current smokers and a slightly greater percentage of individuals with personal histories of diabetes than controls, but the cases and controls did not differ substantially regarding family history of PC.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the six retrospective case–control studies from the Pancreatic Cancer Case–Control Consortium (PanC4)

| Case (N = 2414) | Control (N = 4528) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | % | N | % |

| Mayo | 925 | 38.3 | 1976 | 43.6 |

| UMN | 185 | 7.7 | 548 | 12.1 |

| MDACC | 388 | 16.1 | 426 | 9.4 |

| UCSF | 262 | 10.9 | 283 | 6.3 |

| Yale | 332 | 13.8 | 643 | 14.2 |

| Italy | 322 | 13.3 | 652 | 14.4 |

| Age, years | ||||

| <49 | 179 | 7.4 | 422 | 9.3 |

| 49–54 | 210 | 8.7 | 427 | 9.4 |

| 55–59 | 308 | 12.8 | 610 | 13.5 |

| 60–64 | 408 | 16.9 | 695 | 15.3 |

| 65–69 | 425 | 17.6 | 771 | 17.0 |

| 70–74 | 408 | 16.9 | 806 | 17.8 |

| ≥75 | 476 | 19.7 | 797 | 17.6 |

| Mean (SD) | 65.1 (10.4) | 64.3 (10.7) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 1357 | 56.2 | 2452 | 54.2 |

| Women | 1057 | 43.8 | 2076 | 45.8 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2316 | 95.9 | 4417 | 97.5 |

| Other | 98 | 4.1 | 111 | 2.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| <25 | 790 | 32.7 | 1375 | 30.4 |

| 25–29 | 902 | 37.4 | 1714 | 37.9 |

| ≥30 | 535 | 22.2 | 829 | 18.3 |

| Unknowna | 187 | 7.7 | 610 | 13.5 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 943 | 39.1 | 2343 | 51.7 |

| Former | 1031 | 42.7 | 1749 | 38.6 |

| Current | 440 | 18.2 | 436 | 9.6 |

| Pack-years of smoking within smoking category | ||||

| Never smoker | 943 | 39.1 | 2343 | 51.7 |

| Former | ||||

| <15 pack-years | 368 | 15.2 | 768 | 17.0 |

| ≥15 pack-years | 663 | 27.5 | 981 | 21.7 |

| Current | ||||

| <15 pack-years | 77 | 3.2 | 94 | 2.1 |

| ≥15 pack-years | 363 | 15.0 | 342 | 7.6 |

| Case (N = 2414) | Control (N = 4528) | |||

| Personal history of diabetes | N | % | N | % |

| No | 1814 | 75.1 | 4068 | 89.8 |

| Yes | 579 | 24.0 | 460 | 10.2 |

| Unknown | 21 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| First-degree family history of PC | ||||

| No | 2247 | 93.1 | 4347 | 96.0 |

| Yes | 159 | 6.6 | 165 | 3.6 |

| Unknown | 8 | 0.3 | 16 | 0.4 |

aInformation on body mass index (BMI) was not collected in the UMN study (n = 733). The remaining (n = 64) were missing from other studies.

Abbreviations: Mayo, Mayo Clinic, MDACC, MD Anderson Cancer Center; PC, pancreatic cancer, UCSF, University of California, San Francisco; UMN, University of Minnesota; Yale, Yale University.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants in the five prospective studies from the Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium (PanScan)

| Case (N = 1268) | Control (N = 4215) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | N | % | N | % |

| ATBC | 322 | 25.4 | 427 | 10.1 |

| EPIC | 533 | 42.0 | 381 | 9.0 |

| NYU-WHS | 11 | 0.9 | 13 | 0.3 |

| PLCO | 212 | 16.7 | 3313 | 78.6 |

| SMWHS | 190 | 15.0 | 81 | 1.9 |

| Age, years | ||||

| <49 | 28 | 2.2 | 58 | 1.4 |

| 49–54 | 65 | 5.1 | 172 | 4.1 |

| 55–59 | 129 | 10.2 | 998 | 23.7 |

| 60–64 | 240 | 18.9 | 1357 | 32.2 |

| 65–69 | 276 | 21.8 | 1064 | 25.7 |

| 70–74 | 288 | 22.7 | 538 | 12.8 |

| ≥75 | 242 | 19.1 | 28 | 0.7 |

| Mean (SD) | 67.2 (8.3) | 62.7 (5.9) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 889 | 70.1 | 3726 | 88.4 |

| Women | 379 | 29.9 | 489 | 11.6 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1050 | 82.8 | 4049 | 96.1 |

| Other | 218 | 17.2 | 166 | 3.9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| <25 | 497 | 39.2 | 1234 | 29.3 |

| 25–29.9 | 543 | 42.8 | 2019 | 47.9 |

| ≥30 | 218 | 17.2 | 929 | 22.0 |

| Unknown | 10 | 0.8 | 33 | 0.8 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 447 | 35.3 | 1543 | 36.6 |

| Former | 247 | 19.5 | 1860 | 44.1 |

| Current | 562 | 44.3 | 806 | 19.1 |

| Unknown | 12 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.1 |

| Pack-years of smoking within smoking category | ||||

| Never smoker | 447 | 35.3 | 1543 | 36.6 |

| Former | ||||

| <15 pack-years | 133 | 10.5 | 602 | 14.3 |

| ≥15 pack-years | 114 | 9.0 | 1258 | 29.8 |

| Current | ||||

| <15 pack-years | 105 | 8.3 | 82 | 1.9 |

| ≥15 pack-years | 457 | 36.0 | 724 | 17.2 |

| Unknown | 12 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.1 |

| Case (N = 1268) | Control (N = 4215) | |||

| Personal history of diabetes | N | % | N | % |

| No | 1088 | 85.8 | 3836 | 91.0 |

| Yes | 121 | 9.5 | 337 | 8.0 |

| Unknown | 59 | 4.7 | 42 | 1.0 |

| First-degree family history of PC | ||||

| No | 590 | 46.5 | 3656 | 86.7 |

| Yes | 24 | 1.9 | 70 | 1.7 |

| Unknown | 654 | 51.6 | 489 | 11.6 |

ATBC, alpha-tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Trial; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; NYU-WHS, New York University Women’s Health Study; PLCO, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; SMWHS, Shanghai Men’s and Women’s Health Study.

Associations of non-O blood type and continuous E-DII variable, and PC risk

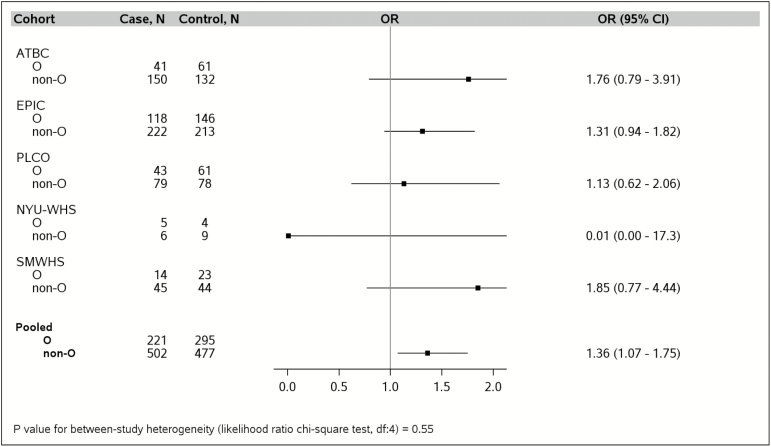

As shown in Figure 1, participants in the PanC4 studies with non-O blood type had increased PC risk compared with those with blood type O. Nearly all the study-specific ORs for the four PanC4 studies with genotype data showed a directionally consistent association, with the exception of MDACC. In the pooled analysis of the PanC4 studies, having a non-O blood type was associated with a 28% increased PC risk (pooled ORnon-O versus O = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.13–1.44; Pheterogeneity = 0.34). Similar results were observed for individuals in the PanScan studies with genotype data (cases n = 723, controls n = 772; pooled ORnon-O versus O = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.07–1.75; Pheterogeneity = 0.55) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Non-O blood type is associated with increased pancreatic cancer risk compared with blood type O in the Pancreatic Cancer Case–Control (PanC4) studies, after adjusting for age (continuous), sex, race (White, other), personal history of diabetes (yes, no), family history of pancreatic cancer (yes, no), BMI (<25, 25-29, ≥30 kg/m2, unknown), pack-years of smoking within smoking category (never, former with <15 pack-years, former with ≥15 pack-years, current with <15 pack-years, current with ≥15 pack-years), and with additional adjustment for study site (Mayo, MDACC, UCSF, Yale) in the pooled estimate. Genotype data were not available in the UMN and the Italian studies. Mayo, Mayo Clinic; MDACC, MD Anderson Cancer Center; UCSF, University of California at San Francisco; Yale, Yale University.

Figure 2.

Increased odds of pancreatic cancer risk among individuals with non-O blood type compared with those with blood type O in the Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium (PanScan) studies, after adjusting for age (continuous), sex, race (White, other), personal history of diabetes (yes, no), family history of pancreatic cancer (yes, no), BMI (<25, 25–29, ≥30 kg/m2, unknown), pack-years of smoking within smoking category (never, former with <15 pack-years, former with ≥15 pack-years, current with <15 packyears, current with ≥15 pack-years), and with additional adjustment for study site (ATBC, EPIC, PLCO, NYUWHS and SMWHS) in the pooled estimate. Analyses were restricted to individuals with genotype data. ATBC, Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Trial; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; NYU-WHS, New York University Women's Health Study; PLCO, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; SMWHS, Shanghai Men's and Women's Health Study.

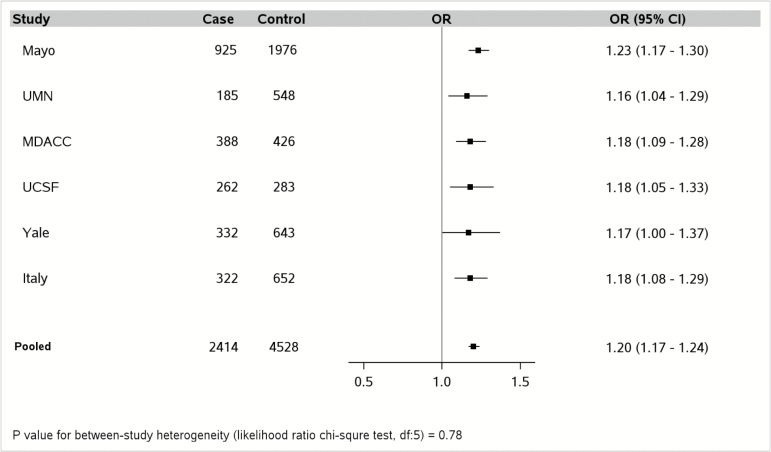

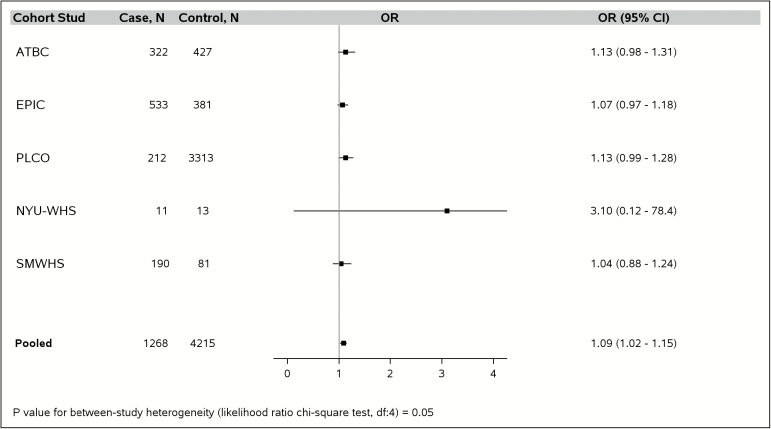

The E-DII scores in the pooled PanC4 data (cases and controls combined) ranged from a maximum anti-inflammatory score of −5.51 to a maximum pro-inflammatory score of 5.07, with mean of −0.86 (standard deviation [SD], 1.87) (Supplementary Table 5, available at Carcinogenesis Online). For the PanScan studies, the E-DII scores in the pooled data ranged from −5.58 to 5.45, with a mean (SD) of −0.17 (1.72) (Supplementary Table 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). All of the PanC4 studies showed similar positive associations between a continuous E-DII score variable and PC risk (Figure 3), with an overall 20% increase in risk for every 1.87 unit increment (corresponding to the SD) in E-DII score (pooled ORcontinuous = 1.20, 95 % CI = 1.17–1.24, Pheterogeneity = 0.78). None of the individual PanScan studies showed a statistically significant association between continuous E-DII score and PC risk; but the pooled analysis showed a significant association with a significantly smaller estimated magnitude of risk (ORcontinuous = 1.09, 95 % CI = 1.02–1.15, Pheterogeneity = 0.05) (Figure 4); difference in effect estimate between-consortium, P-value = 0.0047.

Figure 3.

Every 1.87 units (i.e., standard deviation) increase in energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index (DII) score (continuous variable) is associated with incremental risk of pancreatic cancer in each of the six Pancreatic Cancer Case–Control Consortium (PanC4) studies, in models that adjusted for age (continuous), sex, race (White, other), diabetes (yes, no), family history of pancreatic cancer (yes, no), BMI (< 25, 25-29, ≥30 kg/m2, unknown), pack-years of smoking within smoking category (never, former with <15 pack-years, former with ≥15 pack-years, current with <15 pack-years, current with ≥15 pack-years) and with additional adjustment for study site (Mayo, UMN, MDACC, UCSF, Yale, and Italy) in the pooled estimate. Mayo, Mayo Clinic; MDACC, MD Anderson Cancer Center; UCSF, University of California at San Francisco; UMN, University of Minnesota; Yale, Yale University; Italy, Italian Case control Study.

Table 4.

Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for association between quintiles of the dietary inflammatory index (DII)a and pancreatic cancer in the five nested case–control studies, and stratified by risk factors of pancreatic cancer; the Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium (PanScan)

| DII Scores | P trend | P interaction § | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |||

| Pooled Overall N, case: control |

239: 844 | 267: 845 | 227: 841 | 303: 843 | 232: 842 | ||

| Age- and study-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.08 (0.82–1.43) | 1.09 (0.82–1.44) | 1.64 (1.25–2.15) | 1.39 (1.05–1.85) | 0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 1.04 (0.78–1.38) | 1.03 (0.77–1.38) | 1.47 (1.11–1.95) | 1.23 (0.92–1.66) | 0.008 | |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never | |||||||

| N, case: control | 100: 349 | 106: 368 | 80: 301 | 100: 278 | 61: 247 | ||

| Multivariable-adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 0.70 (0.45–1.09) | 0.82 (0.51–1.30) | 1.31 (0.83–2.07) | 0.86 (0.52–1.43) | 0.57 | |

| Former | |||||||

| N, case: control | 63: 367 | 45: 333 | 44: 388 | 58: 387 | 37: 385 | ||

| Multivariable-adjustedb,c | 1.00 (ref) | 1.36 (0.73–2.54) | 1.01 (0.54–1.87) | 1.44 (0.78–2.65) | 0.98 (0.49–1.96) | 0.86 | |

| Current | |||||||

| N, case: control | 73: 127 | 114: 144 | 102: 149 | 144: 176 | 129: 210 | ||

| Multivariable-adjustedb,c | 1.00 (ref) | 1.68 (0.98–2.89) | 1.70 (0.99–2.93) | 2.26 (1.33–3.84) | 2.20 (1.29–3.74) | 0.003 | 0.62, 0.70 |

| Among individuals with genotype data |

|||||||

| DII Scores d | |||||||

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |||

| Pooled Overall N, case: control |

131: 154 | 143: 155 | 132: 154 | 166: 156 | 151: 152 | ||

| Age- and study-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.09 (0.76–1.58) | 1.15 (0.79–1.66) | 1.54 (1.08–2.21) | 1.58 (1.10–2.28) | 0.003 | |

| Multivariable-adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 1.01 (0.69–1.47) | 1.07 (0.73–1.56) | 1.40 (0.96–2.03) | 1.44 (0.99–2.12) | 0.02 | |

| ABO blood type | |||||||

| O | |||||||

| N, case: control | 48: 56 | 46: 61 | 45: 56 | 46: 59 | 36: 63 | ||

| Multivariable-adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 0.83 (0.45–1.54) | 0.94 (0.50–1.74) | 1.07 (0.57–1.99) | 1.04 (0.39–1.43) | 0.64 | |

| Non-O | |||||||

| N, case: control | 83: 98 | 97: 94 | 87: 98 | 120: 97 | 115: 89 | ||

| Multivariable-adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 1.14 (0.71–1.85) | 1.14 (0.70–1.85) | 1.62 (1.01–2.61) | 2.05 (1.26–3.35) | 0.002 | 0.13, 0.07 |

ATBC, Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Trial; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; NYU-WHS, New York University Women’s Health Study; PLCO, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; SMWHS, Shanghai Men’s and Women’s Health Study.

aThe dietary inflammatory index (DII) scores were energy-adjusted per 1000 calories consumed to account for differing levels of energy intake among participants and categorized into quintiles based on sex-specific distribution among controls in each cohort separately.

bAdjusted for age (continues), sex, race (White, other), diabetes (yes, no), family history of pancreatic cancer (yes, no), BMI (< 25, 25–29, ≥30 kg/m2, unknown) and pack-years of smoking within smoking category (never, former with <15pack-years, former with >15 pack-years, current with <15 pack-years, current with ≥15 pack-years) and study site (ATBC, EPIC, PLCO, NYU-WHS, and SMWHS). No adjustment was done for a particular risk factor in the model that was stratified by the respective factor (e.g. no adjustment for cigarette smoking in smoking stratified analyses).

cAdditional adjustment for pack-years of smoking among former and current smokers.

dThe DII variable was categorized into quintiles among controls with genotype data and the analyses were restricted to individuals with genotype data.

§The first interaction P-value was derived from use of the DII quintiles (df = 4) and the second represent use of DII as a continuous variable.

We also evaluated an a priori hypothesis that an association between the E-DII scores and PC risk might reflect reverse causation, wherein subclinical PC may cause individuals to consume more easily digestible pro-inflammatory foods (e.g. diets rich in carbohydrate and fat). The possibility of reverse causation was examined by excluding cases diagnosed <2 years after recruitment into the PanScan studies. The results from this restricted pooled analysis (cases n = 1115; controls, n = 4215) is very similar to the results of the overall pooled analysis in PanScan (ORcontinuous = 1.09, 95% CI=1.03–1.17, Pheterogeneity = 0.05). Because Asian diets are substantially different from Western diets, we performed a separate subanalysis that excluded the SMWHS data; the association remained essentially the same but with significant heterogeneity between studies (cases n = 1078; controls n = 4134; ORcontinuous = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.04–1.19; Pheterogeneity = 0.02). The SMWHS data were included in remaining analyses. In a post hoc sensitivity analysis, we examined the association between continuous E-DII variable and PC risk (1) with and without additional adjustment for alcohol intake and (2) with exclusion of alcohol from calculation of the E-DII but adjusted for alcohol intake in the model; the results did not differ materially from the results presented above (data not presented).

Associations of E-DII quintiles and stratified analyses by risk factors of PC

The E-DII scores were categorized into quintiles separately in each individual study based on sex-specific control distribution and then pooled after the sex- and study-specific categorization for analyses in PanC4 and PanScan, separately. For the PanC4 studies, we found a dose-dependent association between increasing E-DII quintiles and PC risk (ORQ5 versus Q1 = 2.20, 95% CI = 1.85–2.61, Ptrend < 0.001) (Table 3). Results from stratified analysis by smoking status in PanC4 showed a consistent pattern of increasing PC risk across quintiles of the E-DII in strata of never, former and current smokers. Because not all participating PanC4 studies had genotype data, we performed a separate analysis between E-DII quintiles and PC risk for studies with genotype data (Mayo, MDACC, UCSF and Yale), followed by stratified analysis by genotype-inferred ABO blood type. The association for these four studies is similar to that observed in the overall PanC4 analysis (ORQ5 versus Q1=2.29, 95% CI = 1.88–2.80, Ptrend < 0.001), and the association was evident in both individuals with type O blood (ORQ5 versus Q1=2.04, 95% CI = 1.49–2.81, Ptrend < 0.001) and those with non-O blood type (ORQ5 versus Q1 = 2.51, 95% CI = 1.94–3.26, Ptrend < 0.001); P for interaction by genotype-inferred blood type = 0.10 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for association between quintiles of the dietary inflammatory index (DII)a and pancreatic cancer in the six retrospective case–control studies, and stratified by smoking and ABO blood type; the Pancreatic Cancer Case–Control Consortium (PanC4)

| DII Scores | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | P trend | P interaction§ | |

| Overall N, case: control |

313: 905 | 378: 908 | 468: 904 | 561: 906 | 694: 905 | ||

| Age- and study-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.21 (1.01–1.45) | 1.53 (1.29–1.82) | 1.81 (1.53–2.14) | 2.40 (2.04–2.84) | <0.0001 | |

| Multivariable- adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 1.20 (1.00–1.45) | 1.51 (1.27–1.81) | 1.71 (1.44–2.04) | 2.20 (1.85–2.61) | <0.0001 | |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never | |||||||

| N, case: control | 132: 489 | 163: 477 | 200: 489 | 209: 467 | 239: 421 | ||

| Multivariable- adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 1.37 (1.04–1.80) | 1.58 (1.22–2.07) | 1.66 (1.27–2.17) | 2.30 (1.77–3.00) | <0.0001 | |

| Former | |||||||

| N, case: control | 148: 371 | 172: 353 | 198: 338 | 241: 348 | 272: 339 | ||

| Multivariable- adjustedb,c | 1.00 (ref) | 1.21 (0.92–1.60) | 1.50 (1.14–1.96) | 1.77 (1.35–2.30) | 2.12 (1.62–2.77) | <0.0001 | |

| Current | |||||||

| N, case: control | 33: 45 | 43: 78 | 70: 77 | 111: 91 | 183: 145 | ||

| Multivariable- adjustedb,c | 1.00 (ref) | 0.75 (0.41–1.37) | 1.26 (0.71–2.23) | 1.66 (0.96–2.88) | 1.70 (1.00–2.89) | 0.001 | 0.60, 0.92 |

| Among studies with genotype data | |||||||

| DII Scores d | |||||||

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |||

| Overall N, case: control |

235: 666 | 308: 667 | 359: 664 | 460: 668 | 545: 663 | ||

| Age- and study-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.33 (1.09–1.63) | 1.59 (1.30–1.94) | 2.02 (1.66–2.45) | 2.62 (2.16–3.17) | <0.0001 | |

| Multivariable- adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 1.30 (1.06–1.61) | 1.52 (1.23–1.86) | 1.86 (1.52–2.27) | 2.29 (1.88–2.80) | <0.0001 | |

| ABO blood type | |||||||

| O | |||||||

| N, case: control | 88: 276 | 127: 271 | 115: 274 | 172: 292 | 198: 296 | ||

| Multivariable- adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 1.49 (1.07–2.08) | 1.29 (0.92–1.80) | 1.83 (1.33–2.52) | 2.04 (1.49–2.81) | <0.0001 | |

| Non-O | |||||||

| N, case: control | 147: 390 | 181: 396 | 244: 390 | 288: 376 | 347: 367 | ||

| Multivariable- adjustedb | 1.00 (ref) | 1.20 (0.91–1.57) | 1.66 (1.28–2.15) | 1.88 (1.45–2.44) | 2.51 (1.94–3.26) | <0.0001 | 0.10, 0.12 |

Mayo, Mayo Clinic; MDACC, MD Anderson Cancer Center; UCSF, University of California at San Francisco; UMN, University of Minnesota; Yale, Yale University; Italy, Italian Case control Study.

aThe dietary inflammatory index (DII) scores were energy-adjusted per 1000 calories consumed and categorized into quintiles based sex-specific distribution among controls separately in each of the six studies (Mayo, UMN, MDACC, UCSF, Yale, Italy).

bAdjusted for age (continuous), sex, race (White, other), diabetes (yes, no), family history of pancreatic cancer (yes, no), BMI (<25, 25–29, ≥30 kg/m2, unknown), pack-years of smoking within smoking category (never, former with <15 pack-years, former with >15 pack-years, current with <15 pack-years, current with ≥15 pack-years), and study site (Mayo, UMN, MDACC, UCSF, Yale, Italy). No adjustment was done for a particular risk factor in the model that was stratified by that risk factor (e.g., no adjustment for cigarette smoking in smoking stratified analyses).

cAdditional adjustment for pack-years of smoking among former and current smokers.

dThe energy-adjusted DII variable was categorized into quintiles among controls in the four studies that had genotype data (Mayo, MDACC, UCSF, Yale) and the analysis was restricted to participants in these studies.

§The first interaction P-value was derived from use of the DII quintile variable (df = 4) and the second was derived from use of a continuous DII variable.

For the five PanScan studies, we found a non-significant increased OR for PC risk in the highest, compared with the lowest, E-DII quintile (ORQ5 versus Q1 = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.92–1.66), with a statistically significant association comparing quintile 4 to quintile 1 (ORQ4 versus Q1 = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.11–1.95), and a significant linear trend across quintiles (Ptrend = 0.008) (Table 4). Unlike the PanC4 results, the stratified analysis by smoking status in PanScan did not show homogenous association across strata of never, former and current smokers; a significant association was found only among current smokers (ORQ5 versus Q1 = 2.20, 95% CI = 1.29–3.74; Ptrend = 0.003) but no interaction by smoking history was observed (Pinteraction = 0.62) (Table 4). Analyses restricted to individuals with genotype data in the PanScan studies also showed elevated OR in the highest E-DII quintile (ORQ5 versus Q1=1.44, 95% CI = 0.99–2.12) with significant linear trend (Ptrend = 0.02). Again, unlike the PanC4 results, when individuals in the PanScan studies were stratified by blood type, higher E-DII scores were associated with increased PC risk only among individuals with non-O blood type (ORQ5 versus Q1 = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.26–3.35, Ptrend = 0.002), but not those with type O blood. Nonetheless, in both PanScan and PanC4, no interaction was observed by genotype-inferred blood type or smoking status (all interaction P-values >0.05). Results for stratified analyses by age, sex, race, BMI, diabetes and family history of PC did not show interaction by any of these factors, except for personal history of diabetes in PanScan, but not PanC4 (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Discussion

We assessed associations of inflammatory potential of diet (measured by E-DII scores) and ABO blood type in relation to PC risk by pooling individual-level data from six retrospective case–control studies in PanC4, followed by replication using five case–control studies nested within prospective cohorts in PanScan. We found that consumption of a pro-inflammatory diet, reflected by higher E-DII scores, is associated with increased PC risk; the association was stronger for the retrospective PanC4 studies than for the prospective PanScan studies. In secondary analyses, we confirmed that genotype-inferred non-O blood type is associated with increased risk of PC, but did not find evidence of interaction between ABO blood type and E-DII scores on risk for PC in PanC4 or PanScan. Moreover, no consistent evidence of interaction by other risk factors of PC, including cigarette smoking, was observed. Together, the findings suggest that a pro-inflammatory dietary pattern and genotype-derived non-O blood type are each individually associated with increased PC risk, and that the two exposures do not interact to influence PC risk.

Two previous case–control studies conducted at Mayo Clinic (14) and in Italy (15) by our collaborators found that a higher E-DII score was associated with a 2.5-fold increased odds of PC risk. In this study, we replicated those findings in a large, multicenter retrospective case–control sample that included the two prior studies, followed by replication with prospectively collected dietary data from PanScan. In previous studies, the DII was construct-validated as a predictor of dietary inflammatory potential (12,13). The E-DII has been associated with serum levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and TNF-α receptor 2, which reflects activation of the TNF-α system (12,13). A previous version of the DII was adapted by an independent group and was associated with plasma levels of IL-6, TNF-α, C-reactive protein and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) (43). The mechanisms for the impact of diet-derived inflammation on PC risk might include increasing systemic levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may reach the pancreas via the bloodstream. Furthermore, some pro-inflammatory food constituents, such as cholesterol and fat, are metabolized in the liver and can form reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, leading to DNA damage, dysregulation of tumor suppressor proteins and ultimately, neoplasia. Related to this, a higher inflammatory potential of diet has been associated with increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (44) and greater degree of liver damage (45).

Studies have shown that germline variation in ABO blood type is associated with risk of certain infectious diseases, cardiovascular disorders and cancer susceptibility (19). The observed increased PC risk associated with non-O blood type is consistent with findings from previous studies (18). However, the precise mechanism(s) underlying the association between blood type and PC is not clear, but might be partly explained by data from two non-cancer GWAS suggesting that antigens of the ABO blood type modulate systemic inflammatory processes (20,23). ABO blood type could thus be hypothesized to influence susceptibility to PC through this mechanism (17,19).

However, despite suggestions that ABO blood type may influence PC risk by modulating inflammation (5,17,19,30), we did not observe interaction between inflammatory potential of diet, and ABO blood type or cigarette smoking (a pro-inflammatory substance) in relation to PC risk. The lack of interaction suggests that these exposures may influence PC risk through different pathways, but could also be due to measurement error in the assessment of the exposures, particularly diet and smoking. Moreover, a common constraint for detection of interaction is the requirement of large sample sizes. While we had adequate sample sizes for the overall primary analyses, the sample sizes reduced substantially in the stratified groups. We sought to mitigate this by using a continuous E-DII variable which reduces the number of parameters (i.e. degrees of freedom) required in the statistical models for detection of interaction, but this also did not show significant interaction between inflammatory potential of diet with either ABO blood type or smoking history.

Limitations of this study include the potential for differential recall of dietary intake between cases and controls in the retrospective studies, which is reflected by higher ORs obtained from the retrospective PanC4 studies compared with the prospective PanScan studies. Since up to 30 different dietary components were used in the retrospective case–control studies to calculate the E-DII, variation in recall from study to study could have influenced the results to some extent. Furthermore, the case–control studies’ recall-based questionnaire on dietary intake could have reflected dietary changes induced by subclinical disease (i.e. reverse causation). Although the 2-year lag analysis performed among the nested case–control studies in PanScan did not confirm this bias, it is plausible, nevertheless, that it exists in the retrospective case–control studies. Another observation was that some of the results from the stratified analyses were not entirely consistent between the PanC4 and PanScan data. Although trends of association were generally similar, there was more modest magnitude of association in PanScan compared to PanC4; this could be due to the inherent limitation of retrospective studies, including information and selection biases, or the relatively smaller sample sizes of the stratified groups in the prospective PanScan studies. One study (UMN) did not collect information on BMI, and information on diabetes, smoking, BMI, and in many of the participating studies, family history of PC were all based on self-report; thus, residual confounding by these factors is possible. Confounding by unmeasured factors also is a possible limitation. Most of the dietary questionnaires asked about food intake in the 12 months prior to enrollment in the studies. While the questionnaires were generally designed to measure usual diet, the 12-month timeframe may not adequately capture usual dietary patterns in the periods in a person’s life that are most relevant to pancreatic tumorigenesis. Major strengths of the study include the use of data from a large, multicenter endeavor through our collaboration in PanC4, followed by replication analysis in PanScan. The large sample sizes made it possible to evaluate interaction by ABO blood type and cigarette smoking and other established risk factors for PC.

In summary, this study confirms and extends previous associations of higher inflammatory potential of diet and increased risk of PC. The results further show that while genotype-inferred non-O blood type is associated with increased PC risk, blood type and dietary inflammatory potential do not interact to influence PC risk. Reducing consumption of pro-inflammatory diet (e.g. high-fat, high-calorie diets) or pro-inflammatory food items may help reduce risk of PC in addition to other health benefits.

Figure 4.

Association between every 1.72 units (i.e. standard deviation) increase in energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index (DII) score (continuous variable) and pancreatic cancer risk among five Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium (PanScan) studies, in models that adjusted for age (continuous), sex, race (White, other), diabetes (yes, no), family history of pancreatic cancer (yes, no), BMI (<25, 25–29, ≥30 kg/m2, unknown), pack-years of smoking within smoking category (never, former with <15 pack-years, former with ≥15 pack-years, current with <15 pack-years, current with ≥15 pack-years) and with additional adjustment for study (ATBC, EPIC, PLCO, NYU-WHS and SMWHS) in the pooled estimate. ATBC, Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Trial; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; NYU-WHS, New York University Women's Health Study; PLCO, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; SMWHS, Shanghai Men's and Women's Health Study.

Funding

This PanC4 studies were supported by funding from multiple sources. The Mayo Clinic Biospecimen Resource for Pancreas Research was supported by The National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant (P50 CA102701 and R25 CA092049). The University of Minnesota Study was supported by NIH/ NCI grant (RO1 CA58697). The MD Anderson Pancreatic Cancer study was supported by the NIH Research Project Grant Program (RO1 CA98380). The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) study was supported in part by NCI grants (RO1s CA59706, CA108370, CA109767, CA89726, and CA098889), and by the Rombauer Pancreatic Cancer Research Fund. Cancer incidence data collection in the UCSF study was supported by the California Department of Public Health, the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (contract N01-PC-35136) awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center. The Yale University Pancreatic Cancer Study was supported by NIH/NCI grant (5R01CA098870). The Italy and Milan studies were supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC, project N. 13203) and within the COST Action (BM1214) EU-Pancreas. N.S. and J.R.H. were supported by the United States National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R44DK103377). The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial was sponsored by National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Prevention, in collaboration with the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics and supported by contracts from the National Cancer Institute [University of Colorado Denver, NO1-CN-25514, Georgetown University NO1-CN-25522, Pacific Health Research Institute NO1-CN-25515, Henry Ford Health System NO1-CN-25512, University of Minnesota, NO1-CN-25513, Washington University NO1-CN-25516, University of Pittsburgh NO1-CN-25511, University of Utah NO1-CN-25524 Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation NO1-CN-25518, University of Alabama at Birmingham NO1-CN-75022, Westat, Inc. NO1-CN-25476, University of California, Los Angeles NO1-CN-25404]. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Trial was supported by funding provided by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, and the U.S. Public Health Service contracts [(N01-CN-45165, N01-RC-45035, N01-RC-37004]. The New York University Women’s Health Study is supported by the National Cancer Institute research grants (R01CA034588,R01CA098661, P30CA016087) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Center grant (ES000260). The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition was supported by the European Commission: Public Health and Consumer Protection Directorate 1993–2004; Research Directorate-General 2005; Ligue contre le Cancer; Societé 3 M; Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale; Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) (France); German Cancer Aid, German Cancer Research Center, Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Germany); Danish Cancer Society (Denmark); Health Research Fund (FIS) of the Spanish Ministry of Health, The participating regional governments and institutions (Spain); Cancer Research UK, Medical Research Council, Stroke Association, British Heart Foundation, Department of Health, Food Standards Agency, the Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom); Greek Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity, Hellenic Health Foundation and Stavros Niarchos Foundation (Greece); Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC) (Italy); Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports, Dutch Prevention Funds, LK Research Funds, Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland) (the Netherlands); Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Scientific Council, Regional Government of Skane and Västerbotten (Sweden); World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF). The Shanghai Men’s and Women’s Health Studies were supported by the National Cancer Institute extramural research grants (R01CA82729, R01CA70867, R01CA124908). The PanScan project is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services.

Disclosures

The DII® is owned solely by the University of South Carolina. J.R.H. owns controlling interest in Connecting Health Innovations LLC (CHI), a company planning to license the right to his invention of the DII from the University of South Carolina in order to develop computer and smart applications for patient counseling and dietary intervention in clinical settings. N.S. is an employee of CHI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants and dedicated staff of the participating studies; The Mayo Clinic Biospecimen Resource for Pancreas Research, the University of Minnesota Pancreatic Cancer study, the MD Anderson Pancreatic Cancer study, The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Pancreatic Cancer Study, the Yale University Pancreatic Cancer Study, and The Italy and Milan Pancreatic Cancer Studies, the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Trial, the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition, and the Shanghai Men’s and Women’s Health Studies.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All participating studies were previously approved by their local Institutional Review Board (IRB). Additional ethics approval was obtained from the Mayo Clinic IRB for this pooled analysis.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- DHQ

diet history questionnaire

- E-DII

energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index

- FFQ

food frequency questionnaire

- IL

interleukin

- OR

odds ratio

- PanC4

Pancreatic Cancer Case–Control Consortium

- PanScan

Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium

- PC

pancreatic cancer

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

References

- 1. Jemal A., et al. (2011)Global cancer statistics. CA. Cancer J. Clin., 61, 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antwi S.O., et al. (2017)Cancer of the pancreas. In Thun M. Linet M.S. Cerhan J.R. Haiman C.A. and Schottenfeld D (eds) Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention, 4th Edition Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 611–634. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siegel R.L., et al. (2017)Cancer statistics, 2017. CA. Cancer J. Clin., 67, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raimondi S., et al. (2009)Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: an overview. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 6, 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wolpin B.M., et al. (2009)ABO blood group and the risk of pancreatic cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 101, 424–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bosetti C., et al. (2013)The role of Mediterranean diet on the risk of pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer, 109, 1360–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nöthlings U., et al. (2007)Flavonols and pancreatic cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol., 166, 924–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Larsson S.C., et al. (2006)Fruit and vegetable consumption in relation to pancreatic cancer risk: a prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 15, 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vrieling A., et al. (2009)Fruit and vegetable consumption and pancreatic cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int. J. Cancer, 124, 1926–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stolzenberg-Solomon R.Z., et al. (2002)Prospective study of diet and pancreatic cancer in male smokers. Am. J. Epidemiol., 155, 783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lopez-Garcia E., et al. (2004)Major dietary patterns are related to plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 80, 1029–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shivappa N., et al. (2014)A population-based dietary inflammatory index predicts levels of C-reactive protein in the Seasonal Variation of Blood Cholesterol Study (SEASONS). Public Health Nutr., 17, 1825–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tabung F.K., et al. (2015)Construct validation of the dietary inflammatory index among postmenopausal women. Ann. Epidemiol., 25, 398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Antwi S.O., et al. (2016)Pancreatic cancer: associations of inflammatory potential of diet, cigarette smoking and long-standing diabetes. Carcinogenesis, 37, 481–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shivappa N., et al. (2015)Dietary inflammatory index and risk of pancreatic cancer in an Italian case-control study. Br. J. Nutr., 113, 292–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Risch H.A., et al. (2010)ABO blood group, Helicobacter pylori seropositivity, and risk of pancreatic cancer: a case-control study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 102, 502–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wolpin B.M., et al. (2010)Pancreatic cancer risk and ABO blood group alleles: results from the pancreatic cancer cohort consortium. Cancer Res., 70, 1015–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Risch H.A., et al. (2013)ABO blood group and risk of pancreatic cancer: a study in Shanghai and meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol., 177, 1326–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liumbruno G.M., et al. (2013)Beyond immunohaematology: the role of the ABO blood group in human diseases. Blood Transfus., 11, 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paré G., et al. (2008)Novel association of ABO histo-blood group antigen with soluble ICAM-1: results of a genome-wide association study of 6,578 women. PLoS Genet., 4, e1000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barbalic M., et al. (2010)Large-scale genomic studies reveal central role of ABO in sP-selectin and sICAM-1 levels. Hum. Mol. Genet., 19, 1863–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qi L., et al. (2010)Genetic variants in ABO blood group region, plasma soluble E-selectin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes. Hum. Mol. Genet., 19, 1856–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melzer D., et al. (2008)A genome-wide association study identifies protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs). PLoS Genet., 4, e1000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang J., et al. (2009)Physical activity, diet, and pancreatic cancer: a population-based, case-control study in Minnesota. Nutr. Cancer, 61, 457–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tang H., et al. (2010)Antioxidant genes, diabetes and dietary antioxidants in association with risk of pancreatic cancer. Carcinogenesis, 31, 607–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zablotska L.B., et al. (2011)Vitamin D, calcium, and retinol intake, and pancreatic cancer in a population-based case-control study in the San Francisco Bay area. Cancer Causes Control, 22, 91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bravi F., et al. (2011)Dietary intake of selected micronutrients and the risk of pancreatic cancer: an Italian case-control study. Ann. Oncol., 22, 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Petersen G.M., et al. (2010)A genome-wide association study identifies pancreatic cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 13q22.1, 1q32.1 and 5p15.33. Nat. Genet., 42, 224–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bosetti C., et al. (2014)Diabetes, antidiabetic medications, and pancreatic cancer risk: an analysis from the International pancreatic cancer case-control consortium. Ann. Oncol., 25, 2065–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amundadottir L., et al. (2009)Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the ABO locus associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Nat. Genet., 41, 986–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wolpin B.M., et al. (2014)Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pancreatic cancer. Nat. Genet., 46, 994–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gohagan J.K., et al. ; Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial Project Team (2000)The prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial of the national cancer institute: history, organization, and status. Control. Clin. Trials, 21(6 Suppl), 251S–272S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Albanes D., et al. (1996)Alpha-Tocopherol and beta-carotene supplements and lung cancer incidence in the alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene cancer prevention study: effects of base-line characteristics and study compliance. J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 88, 1560–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A., et al. (2005)Postmenopausal levels of sex hormones and risk of breast carcinoma in situ: results of a prospective study. Int. J. Cancer, 114, 323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Riboli E., et al. (2002)European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr., 5, 1113–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xu W.H., et al. (2007)Joint effect of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption on mortality. Prev. Med., 45, 313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elena J.W., et al. (2013)Diabetes and risk of pancreatic cancer: a pooled analysis from the pancreatic cancer cohort consortium. Cancer Causes Control, 24, 13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Childs E.J., et al. (2015)Common variation at 2p13.3, 3q29, 7p13 and 17q25.1 associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Nat. Genet., 47, 911–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao S.X., et al. ; China Consortium for the Genetics of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease (2013)Robust evidence for five new Graves’ disease risk loci from a staged genome-wide association analysis. Hum. Mol. Genet., 22, 3347–3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Willett W.C., et al. (1987)Validation of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire: comparison with a 1-year diet record. J. Am. Diet. Assoc., 87, 43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shivappa N., et al. (2014)Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr., 17, 1689–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harmon B.E., et al. (2017)The dietary inflammatory index is associated with colorectal cancer risk in the multiethnic cohort. J. Nutr., 147, 430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Woudenbergh G.J., et al. (2013)Adapted dietary inflammatory index and its association with a summary score for low-grade inflammation and markers of glucose metabolism: the Cohort study on Diabetes and Atherosclerosis Maastricht (CODAM) and the Hoorn study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 98, 1533–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shivappa N., et al. (2016)Inflammatory potential of diet and risk for hepatocellular cancer in a case-control study from Italy. Br. J. Nutr., 115, 324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cantero I., et al. (2017)Dietary Inflammatory Index and liver status in subjects with different adiposity levels within the PREDIMED trial. Am J Clin Nutr., 17, 30238–30238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.