Description

A 10-month-old male infant was brought to us with developmental stagnation since 5 months of age. He attained age-appropriate developmental milestones until 5 months of age, however over the next 2 months, he did not gain any new milestones followed by subsequent developmental regression in the form of loss of neck holding ability, social smile, mother regard, visual fixation and cooing. He was a first born to non-consanguineous parents, at term by caesarean delivery (due to non-progression of labour). The antenatal and perinatal periods were normal. There was no history of seizures, exaggerated startle response and extrapyramidal symptoms. The family history was unremarkable. On examination, he had normal head size (46.2 cm, 50th centiles), dysmorphic facial features (flat nasal bridge, hypertelorism, thick upper lip and upturned nose), bilateral cherry-red spots, extensive Mongolian spots (figure 1) and hepatomegaly. He also had generalised hypotonia, hyperactive muscle stretch reflexes and bilateral extensor plantar response. In view of infantile onset neuroregression, dysmorphic facial features, extensive Mongolian spots and bilateral cherry-red spots, clinical diagnosis of GM1 and GM2 gangliosidosis, galactosialidosis, sialidosis and α-fucosidosis were considered.

Figure 1.

Extensive Mongolian spots over the back, lumbosacral region and buttocks.

Skeletal radiographs did not reveal any abnormality. MRI of the brain showed T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence hyperintense signal changes in bilateral cerebral, basal ganglia and bilateral cerebellar white matter with few punctate foci of diffusion restriction (figure 2). Next-generation sequencing revealed a compound heterozygous variant in exon 4 (c. 535_536delGT) and exon 13 (c. 1591dupA) of HEXB gene, confirming a diagnosis of Sandhoff’s disease.

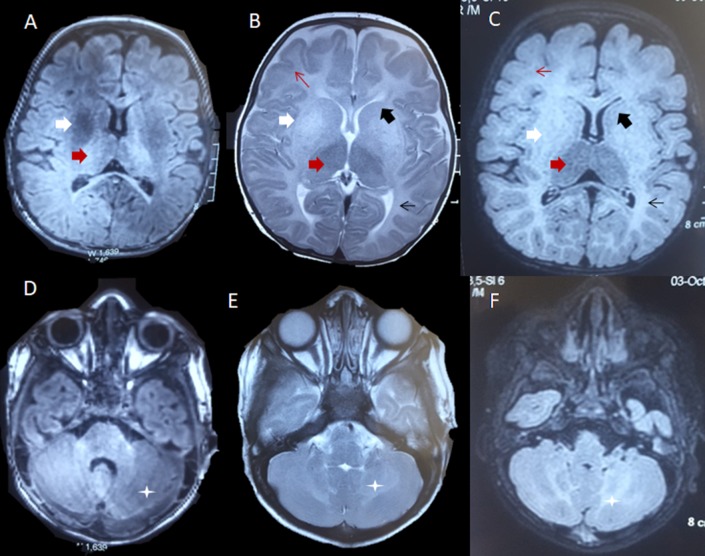

Figure 2.

MRI of the brain. T1-weighted axial images (A, D) showing heterogeneous hyperintense signal changes in thalami (red arrow) and hypointense signal changes in bilateral putamen (white arrow) and cerebellar white matter (asterisk). T2-weighted (B, E) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence (C, F) sequences showing bilateral symmetrical diffuse hyperintensities in periventricular (thin black arrow) and subcortical white matter (thin red arrow), as well as the bilateral cerebellar white matter (asterisk). These signal changes were also noted in bilateral caudate nuclei (black arrow) and putamen (white arrow).

Sandhoff’s disease is a rare autosomal-recessive, lysosomal storage disorder secondary to enzyme hexosaminidase A and B deficiency (due to an abnormal β-subunit). The infantile form is characterised by subtle dysmorphism, macrocephaly, progressive neuroregression, central hypotonia, bilateral macular cherry-red spots, hyperacusis and organomegaly secondary to systemic accumulation of sphingolipids.1 Mongolian spots are dark blue-coloured marks, usually present over the lumbosacral and gluteal regions, commonly found in dark-skinned infants. Most Mongolian spots are hereditary or developmental in nature, but rarely may be associated with a widespread systemic disorder like GM1 gangliosidosis, Hurler’s syndrome, mucolipidosis, mannosidosis, Niemann-Pick disease and very rarely with the Sandhoff’s disease.2 Majority of patients with Sandhoff’s disease presents with macrocephaly, however small proportion may have normocephaly or even microcephaly, and this may be due to significant neuronal loss in early infancy.3 Extensive Mongolian spots coupled with dysmorphic facial features, normocephaly, bilateral cherry-red spots and organomegaly suggest a diagnosis of GM1 gangliosidosis. Our case highlights that presence of normal head size and extensive Mongolian spots should not deter a paediatric neurologist from suspecting a diagnosis of Sandhoff’s disease in the presence of other clinical manifestations.

Learning points.

Presence of extensive Mongolian spots with dysmorphism and developmental delay should raise a suspicion of storage disorder.

Bilateral cherry-red spots coupled with characteristic MRI changes are an important clue to the diagnosis.

Dysostosis multiplex may not be present in the early stage of the disease.

Footnotes

Contributors: IKS: patient management, literature review and initial draft manuscript preparation. LS: clinician-in-charge, critical review of manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. MSR: patient management, literature review and initial draft manuscript preparation. CKA: analysis of the radiological data, critical review of manuscript and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Beker-Acay M, Elmas M, Koken R, et al. Infantile type sandhoff disease with striking brain mri findings and a novel mutation. Pol J Radiol 2016;81:86–9. 10.12659/PJR.895911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloch LD, Matsumoto FY, Belda W, et al. Dermal melanocytosis associated with GM1-gangliosidosis type 1. Acta Derm Venereol 2006;86:156–8. 10.2340/00015555-0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karimzadeh P, Jafari N, Nejad Biglari H, et al. GM2-Gangliosidosis (sandhoff and tay sachs disease): diagnosis and neuroimaging findings (an iranian pediatric case series). Iran J Child Neurol 2014;8:55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]