Abstract

Objective

Early Warning Scores (EWSs) are used to monitor patients for signs of imminent deterioration. Although used in respiratory disease, EWSs have not been well studied in this population, despite the underlying cardiopulmonary pathophysiology often present. We examined the performance of two scoring systems in patients with respiratory disease.

Design

Retrospective cohort analysis of vital signs observations of all patients admitted to a respiratory unit over a 2-year period. Scores were linked to outcome data to establish the performance of the National EWS (NEWS) compared results to a locally adapted EWS.

Setting

Nottingham University Hospitals National Health Service Trust respiratory wards. Data were collected from an integrated electronic observation and task allocation system employing a local EWS, also generating mandatory referrals to clinical staff at set scoring thresholds.

Outcome measures

Projected workload, and sensitivity and specificity of the scores in predicting mortality based on outcome within 24 hours of a score being recorded.

Results

8812 individual patient episodes occurred during the study period. Overall, mortality was 5.9%. Applying NEWS retrospectively (vs local EWS) generated an eightfold increase in mandatory escalations, but had higher sensitivity in predicting mortality at the protocol cut points.

Conclusions

This study highlights issues surrounding use of scoring systems in patients with respiratory disease. NEWS demonstrated higher sensitivity for predicting death within 24 hours, offset by reduced specificity. The consequent workload generated may compromise the ability of the clinical team to respond to patients needing immediate input. The locally adapted EWS has higher specificity but lower sensitivity. Statistical evaluation suggests this may lead to missed opportunities for intervention, however, this does not account for clinical concern independent of the scores, nor ability to respond to alerts based on workload. Further research into the role of warning scores and the impact of chronic pathophysiology is urgently needed.

Keywords: thoracic medicine, risk management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data were obtained from a large clinical vital signs database with clear identification of specialty allowing for subgroup analysis. All observations were included in the analysis, regardless of whether there had previously been a high score which may have resulted in a change of management by the clinical team.

Granularity of data collection in the database allowed for reliable identification of patients meeting the exclusion criteria. Only 0.2% of the observations recorded during the study period were identified as being incomplete.

The retrospective nature of study precludes conclusions relating to impact of introducing National Early Warning Score on mortality.

DNACPR (Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) decisions were not linked as part of the analysis.

Inherent inaccuracy in recording time of death in hospital records means 24 hours cut-off may not be always be exact.

Background

Early Warning Scores (EWSs) combine vital sign measures into a composite score in order to identify patients at risk of clinical deterioration, guide early intervention and reduce avoidable mortality. Scores have evolved over the last 30 years following the recognition that patients experiencing a serious adverse event, such as unplanned transfer to intensive care, in-hospital cardiac arrest or death, showed evidence of pathophysiology in their vital signs observations in the hours leading up to overt deterioration. Initially, this information was captured in the form of single parameter scores where significant derangement in a single vital sign or clinical concern triggered a set clinical response. In the UK, this led to the development of aggregate weighted scores, whereby each vital sign is given a weighting depending on how far outside the predetermined normal range it falls; the sum of these scores is then used to guide response.

In 2012 the Royal College of Physicians published the National EWS (NEWS) protocol in an attempt to standardise processes for identifying patients at risk of imminent deterioration.1 EWS protocols guide decisions around patient care by mandating when a patient with evidence of pathophysiology, in the form of deranged vital signs, should be reviewed by a clinical member of staff, and therefore influence overall clinical workload and resource allocation for all inpatients. Patients with respiratory disease make up a large proportion of a hospital’s inpatient population, however, it is recognised that chronic physiological disturbance caused by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may render NEWS less discriminative when compared with an unselected medical population.2 This has significant implications for patients, in terms of increased observations and interventions, and to clinical staff in terms of workload and potential for alert fatigue. Consequently, attempts have been made to improve the score in this population.3

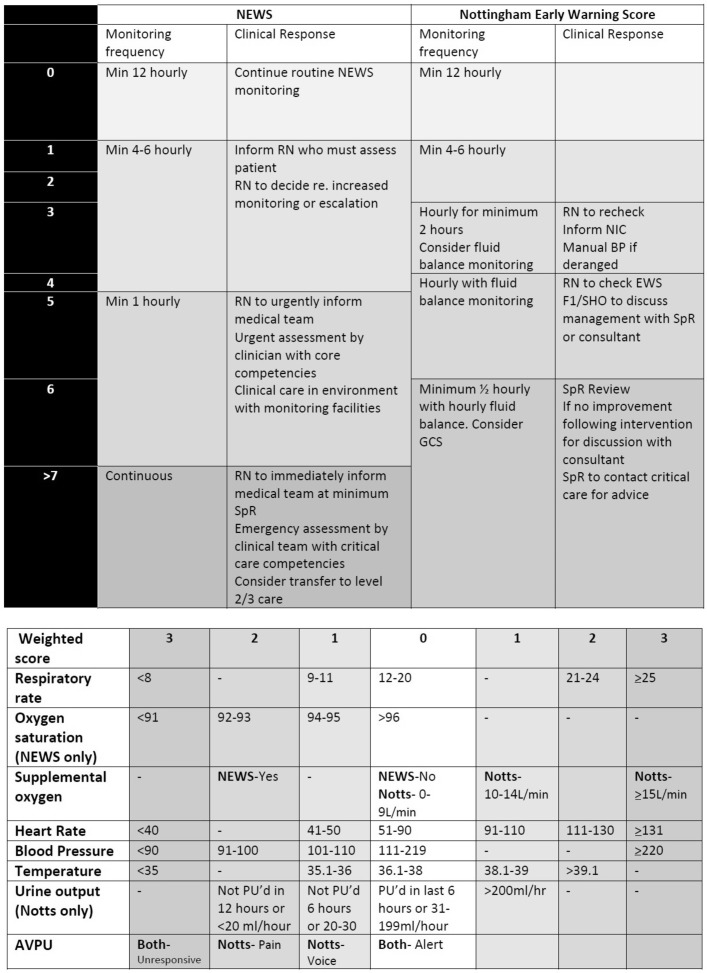

Nottingham University Hospitals National Health Service (NHS) Trust (NUHT) employs an electronic observations system with mandatory escalation based on an adapted EWS. The Nottingham EWS, unlike NEWS, does not score oxygen saturations and has a graduated approach to weighting for both oxygen delivery and level of consciousness. As a more general marker of morbidity, it also employs urine output. We compared the sensitivity and specificity of the two scores in predicting mortality within 24 hours of a set of observations being recorded at the clinical cut points determined by the associated protocols and examined the potential impact in terms of workload of using the locally designed EWS versus NEWS (see figure 1) in patients with respiratory disease based on analysis of the vital signs observations and outcomes of patients admitted to the respiratory department in Nottingham over a 2-year period. We then went on to answer the same questions in a subgroup of patients who were admitted with a diagnosis of COPD to examine the performance of the two scores in this cohort.

Figure 1.

Vital signs weighting and escalation protocol for NEWS and Nottingham University Hospitals EWS. BP, blood pressure; EWS, Early Warning Score; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; NEWS, National Early Warning Score; NIC, Nurse in Charge; PU’d, Passed urine; RN, Registered Nurse; SHO, Senior House Officer; SpR, Specialty Registrar.

Methods

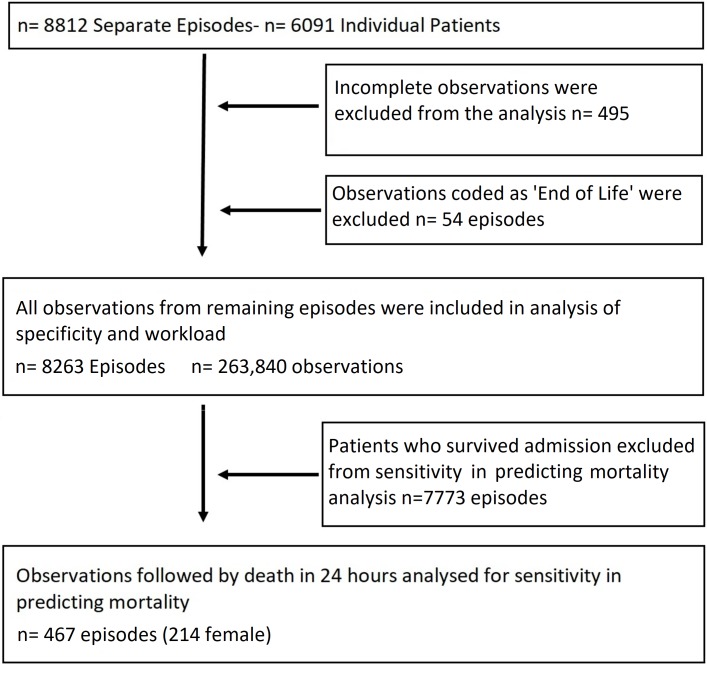

We performed a single centre retrospective analysis of all patients admitted to the respiratory department at NUH NHS Trust between 01 April 2015 and 31 March 2017. This is a tertiary referral centre for respiratory medicine, with one specialist admissions ward and three inpatient wards. The analysis included all adults admitted with respiratory disease not transferred to a higher level of care, that is, high dependency or intensive care, greater than 24 hours before death as these areas are not currently employing electronic observations, long-term ventilator dependent patients were also excluded as hospital policy dictates that these patients are always admitted to the high dependency unit. Following approval from the NHS Information Governance Lead, and in line with existing permissions within the East Midlands Academic Health Sciences Network, data from the integrated electronic observation and communication system comprising respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, conscious level (Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive- AVPU score) and urine output were anonymised by an NHS data analyst prior to extraction from the clinical server. The same system also automatically generates mandated escalation and referral at set scoring thresholds via a predetermined protocol. Scores from the local EWS were linked to demographics and mortality outcomes prior to extraction. NEWS criteria were applied retrospectively to determine how many patients would have been escalated if the NEWS systems were followed. Results were analysed using STATA V.15. The entire data set was analysed for measurement of escalation patterns, analysis of workload and sensitivity and specificity in predicting death within 24 hours of an observation.4 A χ2 analysis was performed to assess whether the difference in escalations was significant. The statistical analysis involved the use of all vital signs observations recorded throughout admission, which were linked to outcome to determine whether they were followed by death within 24 hours of the observation timestamp created by the input devices at the bedside. Observations coded as end-of-life care following clinical decision were excluded from mortality analysis (see figure 2). A further subgroup analysis was then performed on patients coded as having COPD at any point in their admission as per ICD-10 (International Classification of Disease Version 10) codes in order to further assess the statistical performance of the two scores in the presence of chronic pathophysiology.

Figure 2.

Cohort flow diagram of exclusion criteria.

Patient and public involvement

Prior to carrying out this work, a questionnaire was performed among stakeholders, in this case 26 medical registrars working in the East Midlands region. All worked in acute trusts that employed either NEWS or the Nottingham EWS as part of a system to highlight patients felt to be at risk of deterioration. Of the stakeholder responders, 70% believed that using EWS failed to highlight all patients who went on to deteriorate and 88% felt that use of an EWS led to unnecessary reviews. All responders felt there were issues in the setting of chronic disease with some chronic patients scoring even at baseline, and 76% felt that alert fatigue due to high EWS was an issue. These findings guided the interrogation of the data in creating the study detailed in this paper. It is also worth noting that similar work presented to patients with recent inpatient experience at NUHT highlighted the belief that sleep was too often interrupted by observations or reviews. However, patients were not involved directly in the design of this study.

Results

A total of 236 840 observation sets were recorded during 8812 inpatient episodes (53.1% female—see table 1) involving 6091 individuals. In-hospital mortality for respiratory patients was 5.9% (n=521) and median length of stay was 4 days (range 0–175).

Table 1.

Population characteristics of study cohort

| Characteristics of the patients in this study | |

| Numbers (%) | |

| Male | 3824 (47) |

| Female | 4438 (53) |

| Total | 8812 |

| Mean age in years | |

| Male | 63.7 |

| Female | 62.7 |

| Total | 63.1 |

| Vital signs | Mean (±SD) |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 87 (16) |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 19 (3) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 130 (22) |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.6 (1) |

| Oxygen saturations (%) | 94 (6) |

A total of 59 434 (25.1%) observations sets were recorded between the hours of 09:00 and 17:00, Monday to Friday (excluding bank holidays). A total of 177 406 (74.9%) were recorded outside of these hours. The local EWS and escalation protocol led to a median of 36 (range 1–148, calculated from the raw data of scores between 3 and 5 each day) scores per day that triggered a medical review (table 2). This included a median of 5 (range 0–41) automated referrals to the resident on call senior clinician (medical registrar) every day. Direct comparison of workload generated for other members of the clinical team was not possible as the escalation protocol for both scores is only directly comparable at registrar level, however, the workload generated at each of the clinically applied cut points can be seen in tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Workload predictions and sensitivity and specificity in predicting death within 24 hours for National Early Warning Score (NEWS) and local EWS for unselected respiratory population

| NEWS band | Mandated escalation to: | % of observations in each band | Median no per day (range) | Sensitivity for predicting death within 24 hours | Specificity for predicting death within 24 hours |

| 0 | Nil | 17.86 | 32 (3–75) | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| 1–4 | Nurse | 67.34 | 180 (21–457) | 99.44 | 15.09 |

| 5–6 | Doctor | 8.82 | 60 (10–184) | 88.64 | 74.51 |

| 7 or more | Registrar | 5.97 | 38 (2–158) | 68.53 | 91.16 |

| NUH EWS band | Mandates escalation to: | % of observations in each band | Median no per day (range) | Sensitivity for predicting death within 24 hours | Specificity for predicting death within 24 hours |

| 0 | Nil | 56.11 | 174 (20–409) | 100.00 | 0 |

| 1–2 | Nurse | 31.83 | 99 (16–300) | 95.49 | 56.32 |

| 3 | Nurse/doctor | 5.39 | 16 (1–116) | 76.65 | 88.24 |

| 4–5 | Doctor | 4.74 | 14 (1–55) | 63.33 | 93.58 |

| 6 or more | Registrar | 1.94 | 5 (0–41) | 41.91 | 98.24 |

NUH, Nottingham University Hospital.

Table 3.

Workload predictions and sensitivity and specificity in predicting death within 24 hours for National Early Warning Score (NEWS) and local EWS for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

| NEWS band | Mandated Escalation | % of observations in each band | Median no (range) | Sensitivity for death within 24 hours | Specificity for death within 24 hours |

| 0 | Nil | 7.96 | 5 (0–23) | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| 1–4 | Nurse | 59.3 | 43 (4–112) | 100.00 | 7.99 |

| 5–6 | Doctor | 22.2 | 16 (1–59) | 89.85 | 67.47 |

| 7 or more | Registrar | 10.54 | 6 (0–47) | 71.07 | 89.68 |

| NUH EWS band | Mandated Escalation | % of observations in each band | Median no (range) | Sensitivity for death within 24 hours | Specificity for death within 24 hours |

| 0 | Nil | 53.89 | 39 (1–101) | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| 1–2 | Nurse | 35.05 | 26 (4–90) | 92.39 | 54.06 |

| 3 | Nurse/doctor | 5.46 | 3 (0–30) | 70.56 | 88.50 |

| 4–5 | Doctor | 4.31 | 2 (0–18) | 58.38 | 94.20 |

| 6 or more | Registrar | 1.28 | 0 (0–19) | 38.07 | 98.75 |

NUH, Nottingham University Hospital.

If NEWS criteria were applied to the same population, it would have generated a median of 98 (range 12–270) escalations to a doctor per day (p<0.001 for difference between scores), with 38 (range 2–158) scores generating automatic referral to the registrar (p<0.001 for difference between scores) per day.

Sensitivity and specificity for predicting in-hospital mortality based on death within 24 hours of a set of vital signs observations point are shown in table 2. At each clinically equivalent band, the sensitivity and specificity in predicting mortality of all patients scoring at and above that cut point are shown. At each cut point, NEWS would have had a higher sensitivity than the local EWS (ie, a higher percentage of patients who went on to die were flagged as requiring escalation), but a lower specificity.

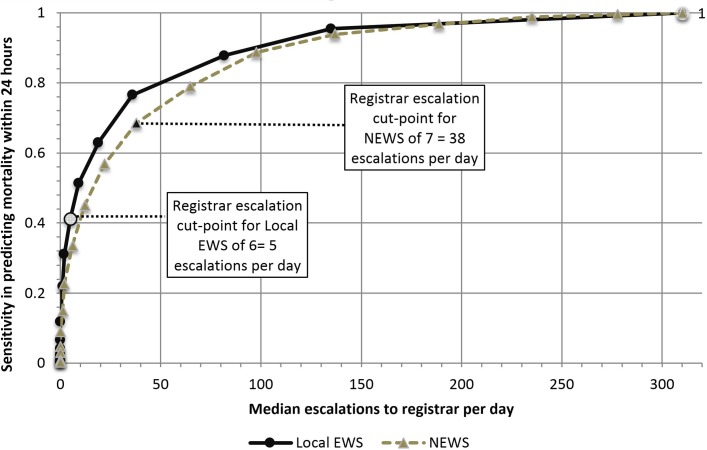

Figure 3 plots sensitivity in predicting mortality, against median number of mandated clinician alerts per day for both EWS types. It demonstrates that for a sensitivity of 0.7, NEWS generates a higher number of mandated escalations. At both extremes of sensitivity (0 and 1) the number of escalations is the same, that is, mandating an escalation at a NEWS or EWS of 0 would mean all patients were escalated, and each score would have 100% sensitivity for predicting mortality (as everyone who died would have been reviewed). Likewise only escalating patients with a maximum EWS or NEWS score would lead to very few patients being escalated.

Figure 3.

Graph of sensitivity versus alerts created for NEWS and local EWS. EWS, Early Warning Score; NEWS, National Early Warning Score.

Further subgroup analysis was performed on admissions with an ICD-10 code for COPD at any point. This yielded 56 345 observations from 2207 episodes by 1365 individual patients. Using the local EWS protocol led to median of 0 (range 0–19) escalations to the registrar, while applying NEWS would have generated a median of 6 (0–47) scores being escalated to the registrar each day. As in the unselected respiratory cohort, NEWS was more sensitive in predicting imminent mortality than the local EWS but with a significantly inferior specificity at each clinical cut point applied (see table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the effect of two different EWS systems in patients admitted with respiratory disease to a tertiary referrals centre. The respiratory department at NUHT manages patients in line with national guidelines and has outcomes comparable with other similar units; consequently linking of raw observations to outcomes prior to analysis enables conclusions which are applicable to other centres.

We analysed the number of mandatory escalations generated and the sensitivity and specificity of both of the scores in predicting imminent in-hospital mortality in an unselected respiratory population and in a subgroup analysis of patients with COPD. Our data show that at the scores’ cut points for escalation, NEWS would have generated a significantly higher workload due to a lower specificity, with a higher sensitivity for predicting imminent deterioration, when compared with the locally used EWS. This was accentuated in patients with COPD, an observation we believe is due to chronic changes in the underlying physiology which influences the way in which these patients respond to acute pathological processes.

Although NEWS may become less relevant with the publication of NEWS2 in December 2017, our study remains relevant. First, it highlights the wider impact of the different approaches to designing a scoring system and the paucity of evidence in relation to how this is evaluated. Second, as it is currently unclear how widely NEWS2 has been adopted by hospitals across the NHS and what the likely roll-out will be, NEWS remains a current clinical tool in many trusts.

Previous work has suggested that NEWS was less discriminative in predicting deterioration in patients with respiratory disease, compared with a population of unselected medical admissions,2 however, NEWS has not previously been studied in large numbers of respiratory patients across an entire admission.

Our study faced similar limitations to others published in this area. These include retrospective study design preventing analysis of the real terms impact of introducing different scores into the study environment on outcomes including length of stay, cardiac arrest rate and mortality; the low prevalence of mortality in the patient population and the subsequent impact on observed effect size; and the difficulty in recording accurate time of death in a general ward setting for use in mortality analysis.

However, our observed findings of an increase workload generated are both novel and important as, when used as part of a system which employs automatic escalation of threshold scores, NEWS leads to a significant impact on workload in a resource pressured environment, with little evidence of improved clinical outcome. While there is a difference in the workload generated when comparing the scoring systems both in a general respiratory population and in patients with COPD, this relates to the cut points for escalation mandated by the protocols, rather than the scores themselves; unsurprisingly overall both scores perform similarly when the individual scores are plotted (they are based on similar clinical observations), however, the mandated cut points differ. The difference created by the protocol design relates to the way in which the scores are used clinically, and can be explained as follows:

The first approach is seen in the scoring thresholds dictated by NEWS. Its cut points for each layer of clinical intervention, that is, escalation to nurse, clinician or registrar, have a higher sensitivity which acts to rule out imminent clinical deterioration in those patients whose vital signs do not meet scoring thresholds, meaning clinicians can be confident that patients with a low score are very unlikely to be at imminent risk. This is akin to a d-dimer where a low value in an individual with low clinical suspicion effectively excludes a venous thromboembolism.5 6 This high sensitivity approach works well in a setting with less highly trained staff delivering the first layer of monitoring. However, if this approach is applied in an unfiltered and automated manner, the workload generated by escalations from patients who never go on to deteriorate will have significant resource and operational implications, as well as increasing the likelihood of unnecessary intervention for patients.

The second approach, used by the local EWS, is one of high specificity in the cut points for escalation, with a relatively lower sensitivity. This approach acts to highlight potential imminent clinical deterioration in those meeting the escalation criteria, but does not always rule out deterioration in those who score under the cut point. This may seem a less preferable approach. However, a recent study of rapid response systems indicated that staff clinical concern in the absence of a qualifying score was responsible for escalation in 47% of calls,7 highlighting the role of staff education and empowerment, over and above EWS protocols. The variability in physiological normal baselines created by patient-specific factors such as comorbidity or fitness means that using vital signs observations alone as the basis for a score leading to mandatory escalation will always require a trade-off between sensitivity in accurately identifying patients potentially at risk of deterioration and staff alarm fatigue generated by patients who do not go onto deteriorate. This is particularly pertinent in resource-limited environments (such as during out of hours care),

Despite the mandated and widespread uptake of EWS, there has been minimal prospective validation of their use. Efforts to improve precision in predicting outcome through scrutiny of large datasets has largely employed analyses utilising area under the receiver operating characteristic curves which are limited by the low prevalence of mortality in the population.8 Before and after studies have largely, but not universally9–11 highlighted the efficacy of EWS, however, no randomised controlled trials have been performed. Consequently, evidence of the scores’ real impact on clinical outcomes, such as mortality, transfer to higher level of care or length of stay, or on workforce outcomes such as workload from excessive task generation and alarm fatigue, has only been obtained from observational studies. These are all limited by significant confounders.

This evidence gap around the clinical and workforce implications of EWS systems will become increasingly important as hospitals move towards automated systems with mandated referral of patients who reach a threshold score. Continuing integration of more data into digital healthcare systems via continuous monitoring, dynamic measures of fitness and electronic health records will further highlight this gap, as without an understanding of how these data can be applied, it will be difficult to differentiate the signal from the noise. Given the growing complexity of the inpatient population more work is urgently required to understand the wider impact of EWS on outcomes such as mortality and length of stay, task burden, working patterns and cost. There is also need to reconsider the role of clinical concern in monitoring patients and how this can be further promoted to prevent future systems depending purely on scores rather than integrating staff skills and intuition into the decision-making process. EWSs should not be developed in isolation based on statistical performance as this fails to recognise that they are a component within the complex clinical environment and therefore need to be designed to enhance, not complicate, the clinical decision-making process. This is particularly important in patients with respiratory disease where physiology is often chronically deranged and less responsive to intervention and a greater understanding of the contributory clinical factors and more individualised approach is required. Although NEWS2 has been developed to address concerns regarding the altered physiology of patients with respiratory disease, the new score was not based on any significant development in the evidence base. Therefore, the same questions currently remain regarding the real terms impact of introducing any EWS, including NEWS2, and the associated software platforms on the patients being monitored, the staff and resources required to deploy it and react to it, and the associated opportunity cost.

Healthcare is becoming increasingly individualised, with significant amounts of digital healthcare data collected. In recognition of this, a possible future direction would be to create scores which, rather than being based solely on observations, integrate other more patient-specific factors such as comorbidity, premorbid fitness and age to apply specific weighting to observations. For example, through applying a lower score to a high respiratory rate in someone who had chronic respiratory disease and could mobilise 5 metres as a baseline as opposed to a young marathon runner, it would be possible to maintain the same scoring thresholds at which a response was triggered, while making those thresholds more meaningful through an evidence-based application of risk of deterioration based on what a clinical observation represents in a particular individual.

Analysis of big data is the first stage to making this possible. However, the ability to demonstrate the significance of changing either scoring thresholds or the scores themselves on patient and system outcomes, driven by an attempt to compensate for changes to existing baseline physiology, will require considerable numbers, novel prospective study design and collaboration across multiple sites and research disciplines.

These points need to be addressed before any meaningful advances are made to ensure the most effective use of resources in the pursuit of improving the safety and efficiency of patient care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SF was first author and performed initial data analysis, literature review and created initial document and revisions. GH is an NHS data analyst who extracted the data for the article and provided editorial input. TMM is a University of Nottingham Statistician who provided statistical advice and oversight with editorial input. DES is the supervising author. In collaboration with the first author, he developed the protocol, advising on data sources and research question while providing editorial input at all stages of the manuscript’s development.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Unpublished metadata from the dataset analysed for this work is available through contacting the authors. However, due to the nature of the raw data, it is not possible to make it freely available due to the limitations placed on the use of the dataset by NHS Information Governance procedures and approvals.

Collaborators: Mark Simmonds was instrumental in delivering the electronic observations system at Nottingham University Hospitals Trust and has liaised with our group in relation to our work on EWS.

References

- 1. Physicians RCo. National Early Warning Score (NEWS): standardising the assessment of acute illness severity in the NHS: Royal College of Physicians, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hodgson LE, Dimitrov BD, Congleton J, et al. . A validation of the National Early Warning Score to predict outcome in patients with COPD exacerbation. Thorax 2017;72:23–30. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eccles SR, Subbe C, Hancock D, et al. . CREWS: improving specificity whilst maintaining sensitivity of the National Early Warning Score in patients with chronic hypoxaemia. Resuscitation 2014;85:109–11. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.08.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jarvis SW, Kovacs C, Briggs J, et al. . Are observation selection methods important when comparing early warning score performance? Resuscitation 2015;90:1–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stein PD, Hull RD, Patel KC, et al. . D-dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:589–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Owaidah T, AlGhasham N, AlGhamdi S, et al. . Evaluation of the usefulness of a D dimer test in combination with clinical pretest probability score in the prediction and exclusion of Venous Thromboembolism by medical residents. Thromb J 2014;12:28 10.1186/s12959-014-0028-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGaughey J, O’Halloran P, Porter S, et al. . Early warning systems and rapid response to the deteriorating patient in hospital: A systematic realist review. J Adv Nurs 2017;73:3119–32. 10.1111/jan.13367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Romero-Brufau S, Huddleston JM, Escobar GJ, et al. . Why the C-statistic is not informative to evaluate early warning scores and what metrics to use. Crit Care 2015;19:285 10.1186/s13054-015-0999-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Subbe CP, Davies RG, Williams E, et al. . Effect of introducing the Modified Early Warning score on clinical outcomes, cardio-pulmonary arrests and intensive care utilisation in acute medical admissions. Anaesthesia 2003;58:797–802. 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Booth C. Effect on outcome of an early warning score in acute medical admissions. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2003;90:1.12488368 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moon A, Cosgrove JF, Lea D, et al. . An eight year audit before and after the introduction of modified early warning score (MEWS) charts, of patients admitted to a tertiary referral intensive care unit after CPR. Resuscitation 2011;82:150–4. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.09.480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.