Abstract

Objectives

We examine the volume–outcome relationship in isolated transcatheter aortic valve implantations (TAVI). Our interest was whether the volume–outcome relationship for TAVI exists on the centre level, whether it occurs equally for different outcomes and how it develops over time.

Design

Secondary data analysis of electronic health records. The comprehensive German Federal Bureau of Statistics Diagnosis Related Groups database was queried for data on all isolated TAVI procedures performed in Germany between 2008 and 2014. Logistic and linear regression analyses were carried out. Risk adjustment was applied using a predefined set of patient characteristics to account for differences in the risk factor composition of the patient populations between centres and over time. Centres performing TAVI were stratified into groups performing <50, 50–99 and ≥100 procedures per year.

Setting

Germany 2008–2014.

Participants

All patients undergoing isolated TAVI in the observation period.

Interventions

None.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

In-hospital mortality, bleeding, stroke, probability of ventilation >48 hours, length of hospital stay and reimbursement.

Results

Between 2008 and 2014, a total of 43 996 TAVI procedures were performed in 113 different centres in Germany with a total of 2532 cases of in-hospital mortality. Risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality decreases over the years and is lower the higher the annual procedure volume at the centre is. The magnitude of the latter effect declines over the observation period. Our results indicate a ceiling effect in the volume–outcome relationship: the volume–outcome relationship is eminent in circumstances of relatively unfavourable outcomes. Alongside improving outcomes, however, the volume–outcome relationship decreases. Also, a volume–outcome relationship seems to be absent in circumstances of constantly low event rates.

Conclusions

The hypothesised volume–outcome relationship for TAVI exists but diminishes and may disappear over time. This should be taken into account when considering mandatory minimum thresholds.

Keywords: valvular heart disease, health economics, cardiology, adult cardiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study based on administrative data; coding errors are inevitable, however cardiovascular diagnosis-related groups are reviewed by independent physicians on behalf of health insurers.

Risk adjustment included a number of parameters whose reliability cannot be fully secured, and we cannot guarantee that all parameters of relevance are included in the model.

Hospital volume was classified into three fixed categories, which is in line with thresholds from official guidelines and previous literature, but might hide possible effects related to very high volumes.

The data set omits baseline diagnoses of pure aortic regurgitation, as well as patients who underwent a concomitant cardiac procedure, which makes sense from a clinical perspective, but complicates comparisons and might cause bias.

The study provides comprehensive data on everyday transcatheter aortic valve implantation practice in a large industrialised country over a multiyear period.

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a rapidly evolving technique for therapy of aortic stenosis, with a very early and pronounced utilisation in Germany.1 Previous studies report hospital-specific learning curves with respect to in-hospital outcomes such as procedural success, mortality and clinical complications of varying lengths and magnitudes.2–6 In general, learning curve effects within and between centres can, to some degree, be explained by the volume of procedures performed at the centre. This relationship can be summed up as the ‘practice-makes-perfect hypothesis’, according to which quality of care either increases with the number of patients as a result of economies of scale, with a competing explanation of ‘selective-referral’, according to which higher quality hospitals attract greater demand and therefore have a greater volume of patients.7 8

There are a number of criticisms on empirical analyses on the volume–outcome relationship: many studies lack appropriate adjustment for differences in the risk factor composition of the patient populations between centres.9 10 Second, most studies focus on in-hospital mortality only,11 which is easy to measure, but it is recommended to include additional quality measurements. Finally, most studies divided patients into groups of equal size for analysing the volume–outcome relationship, which makes it difficult to make use of such results when justifying specific volume thresholds.6 12–14

Although the evidence regarding the existence of an inverse relationship between the number of TAVI procedures and related outcomes is limited,15 16 medical authorities in Germany and several other countries have issued guidelines calling for minimum numbers of procedures for primary operators performing TAVI.17–20 There however remains some question whether, first, the volume–outcome relationship outlined above exists on the centre level regarding TAVI and, second, whether or not it takes place in all outcomes and complications equally, and how an existing volume–outcome relationship might change over the years.

To address these questions, we calculated annual procedure volumes for all German hospitals that performed TAVI procedures between January 2008 and December 2014. In order to account for differences in the patient population between high, medium and low-volume centres and over time, we carried out baseline-adjusted regression analyses for the endpoints in-hospital mortality, bleeding, stroke, probability of ventilation >48 hours, length of hospital stay and reimbursement.

Methods

Data

Since 2005, data on all hospitalisations in Germany have been available for scientific use via the Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) statistics collected by the Research Data Center of the Federal Bureau of Statistics (DESTATIS). These hospitalisation data, including diagnoses and procedures, are a valuable source of representative nationwide data on the in-hospital treatment of patients. This database represents a virtually complete collection of all hospitalisations in German hospitals that are reimbursed according to the DRG system. From this database,1 we have extracted data on 43 996 cases of isolated TAVI for our analysis.

Our study did not involve direct access by the investigators to data on individual patients but only access to summary results provided by the Research Data Center. Therefore, approval by an ethics committee and informed consent were determined not to be required, in accordance with German law. All summary results were anonymised by DESTATIS. In practice, this means that any information allowing the drawing of conclusions regarding a single patient or a specific hospital is censored by DESTATIS to guarantee data protection. Especially the use of the anonymous, persistent ‘institute indicator of hospitals’ is highly restricted in order not to publish any information directly attributable to a single hospital.

As described previously,1 21 we were able to use the OPS codes (OPS codes: 5-35a.0 in 2007 and 5-35a.00, 5-35a.01 and 5-35a.02 from 2008) to identify all TAVI procedures performed (and reimbursed) in Germany between 2008 and 2014. Patients with a baseline diagnosis of pure aortic regurgitation (main or secondary diagnosis other than I35.0, I35.2, I06.0, I06.2) and those with concomitant cardiac surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention were not included in this analysis. Although some concomitant procedures might be informative (a cardiac surgery procedure during the same hospital stay as TAVI might likely represent a complication following a TAVI procedure), these cases cannot be consistently identified in our data set as, in many cases, concomitant procedures might have taken place in another centre. A complete list of procedure codes can be found in online supplementary table S1; a more detailed discussion of the data source may be found in a previous manuscript.1 21

bmjopen-2017-020204supp001.pdf (133.4KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research question was guided by the intention to provide hospitals and policymakers with empirical evidence that enables them to structure the infrastructure in such a way as to deliver the best possible outcomes to patients. The selected outcome measures represent the most severe complications to the procedure and are of high significance to patient quality of life after the intervention. There was, however, no direct involvement of patients in the design, the recruitment and conduct of the study, nor will the results be disseminated to study participants as the study was based on anonymised administrative data.

Measures

Regarding the in-hospital complications, bleeding was defined as requiring a transfusion of more than 5 units of red cells. For all other comorbidities and complications the existing anamnestic or acute distinctive codes were used (we have discussed OPS and ICD codes in greater detail previously21).

In order to analyse possible effects of the above discussed mandatory minimum quantities, the number of procedures per year and centre was categorised (ie, n<50, 50≤n<100, n≥100) on the basis of an anonymous, persistent ‘institute indicator of hospitals’ provided by DESTATIS. These particular thresholds are applied because the minimum number of 50 procedures is often mentioned in official TAVI guidelines,17–20 and these thresholds are widely applied in the literature.22–24

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes include postprocedural complications such as stroke and bleeding events (transfusion of ≥5 red cells), as well as reimbursement, length of hospital stay and proportion of patients with ventilation >48 hours.

Statistical analysis

In a first step, multivariate regression analyses were carried out for the different endpoints. In a previous study, Reinöhl et al 1 identified 21 baseline patient characteristics to describe risk profiles between procedural groups. For risk adjustment, all of these 21 baseline patient characteristics were included as covariates (all covariates listed in table 1) in the respective regression analyses. In addition, an interaction term between time (in years) and the above mentioned annual volume categories was included in the regression analyses in order to investigate the volume–outcome relationship over the years.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (2008–2014)

| n | 43 996 |

| Female | 55.87% |

| Age in years, mean/SD | 80.95/6.11 |

| Estimated logistic EuroSCORE*, mean/SD | 22.21%/13.57% |

| Aortic valve stenosis as main diagnosis | 68.22% |

| Combined aortic valve diseases as main diagnosis | 26.56% |

| Heart failure | |

| NYHA II | 8.26% |

| NYHA III or IV | 41.66% |

| Hypertension | 62.66% |

| CAD | 46.88% |

| Previous myocardial infarction | |

| Within 4 months | 1.59% |

| Within 1 year | 0.75% |

| After 1 year | 4.35% |

| Previous CABG | 12.75% |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 18.06% |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 12.39% |

| Carotid disease | 6.17% |

| COPD | 15.14% |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 22.32% |

| Renal disease | |

| GFR <15 mL/min | 2.95% |

| GFR <30 mL/min | 4.90% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 45.93% |

| Diabetes | 33.30% |

*For calculation of the logistic EuroSCORE, we were able to populate all fields except for critical preoperative state and left ventricular function. In these we assumed an inconspicuous state (ie, no critical preoperative state and no left ventricular dysfunction) and thus calculated a best‐case scenario.

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; NYHA, New York Heart Association Functional Classification.

Please note that in comparison to the data published by Reinöhl et al, one transapical TAVI procedure (in 2010) needed to be removed from the data set due to incomplete information.

Logistic and linear regression analyses are applied for dichotomous and continuous endpoints, respectively. The question of how to account for patients treated in the same hospital was discussed previously.13 25 26 As recommended in a previous study that also used data from the German DRG statistic,13 we used cluster-robust SEs to account for this dependency.

Risk-adjusted rates and means within each year and hospital volume category were obtained by computing the corresponding predicted probabilities or means, respectively, for an artificial subject with each confounder set to its mean value (prediction at the means, see table 1 for mean values of all confounders). Thereby, risk-adjusted rates and means are taking two aspects into account: (1) change in the patients’ risk factor compositions over the years, and (2) differences in the patients’ risk factor compositions within different hospital volume categories. Risk-adjusted rates and means are therefore interpreted as the ‘true’ procedure-related outcomes independent of changes in the patient population over the years and differences between low, medium and high-volume centres. Please note that this implies the assumption that all outcome relevant parameters are used for risk adjustment. Unfortunately, we cannot guarantee that all parameters of relevance are included in the model. In fact, the administrative data set lacks relevant clinical information (such as echocardiographic findings or anatomical characteristics).

The visualisation of these risk-adjusted rates or means together with their 95% CIs constitutes the main analytical approach in this paper. To assess the statistical significance of the observed volume–outcome relationship, of the time trend and a potential change of the volume–outcome relationship over time, we applied to the estimated rates or means a random effects meta-regression (command metareg27) with time and volume as continuous covariates. A model with an interaction term was used to assess the change in the volume–outcome relationship. A model without an interaction was used to assess the main effects.

Standardised reimbursement data are only available starting in 2010 due to a change in the reimbursement system making previous data difficult to compare. In Germany, reimbursement is based on DRGs which are defined by the patients' diagnoses, gender and age, treatment procedures, complications or comorbidities and further attributes. Based on these data, a predetermined reimbursement rate per case is calculated. Hospitals receive additional reimbursement for long-stay outlier cases.28 Furthermore, additional reimbursement is possible for very complex intensive care treatments, which have to be proven by documentation of illness severity and treatment effort during intensive care unit stay.29

All analyses were carried out using Stata V.13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Between 2008 and 2014, a total of 43 996 TAVI procedures were performed in 113 different centres in Germany. The total number of TAVI procedures performed per year increased markedly over the observation period, from 1122 in 2008 to 11 559 in 2014 (see table 2).

Table 2.

Number of procedures with regard to the performed TAVI volume of a distinct centre in a given year

| TAVI volume in centre | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

| <50 procedures, n | 613 (40) | 1234 (61) | 1155 (51) | 1107 (43) | 960 (36) | 765 (31) | 617 (30) |

| 50–99 procedures, n | 236 (3) | 658 (10) | 1875 (26) | 1957 (27) | 1569 (20) | 1930 (25) | 1135 (16) |

| ≥100 procedures, n | 273 (NA*) | 707 (NA) | 1776 (3) | 3459 (7) | 5711 (16) | 6452 (9) | 9807 (20) |

| Total number, n | 1122 (≥44) | 2599 (≥72) | 4806 (80) | 6523 (77) | 8240 (72) | 9147 (65) | 11 559 (66) |

Please note that the numbers of procedures performed per year at a given centre were not constant over the observation period, so that it is possible for a centre to fall into a different volume group in a different year. Number of centres in parentheses.

*NA, not available, exact number censored by the Research Data Center of the Federal Bureau of Statistics (DESTATIS) due to data protection concerns.

TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantations.

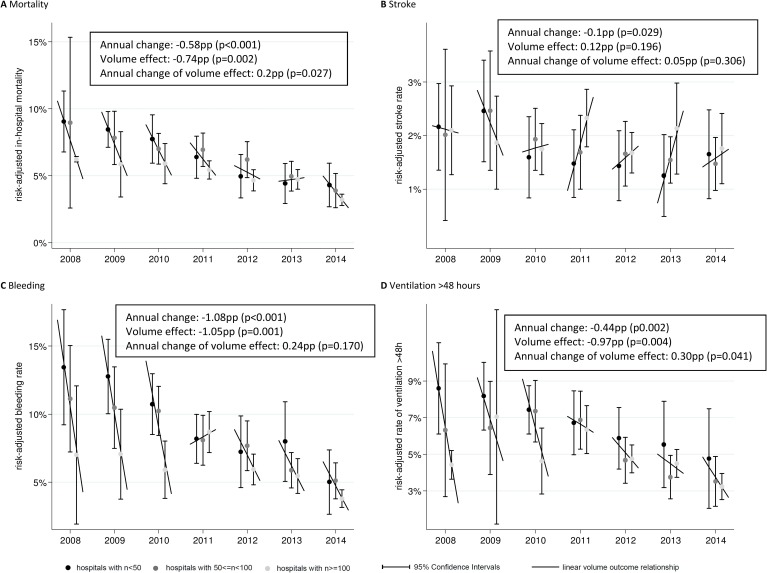

As reported previously,1 substantial reductions in in-hospital mortality have been achieved between 2008 and 2013, and we find this trend to continue into 2014. Regarding centre-specific procedure volumes of all TAVI procedures, it appears that the differences in unadjusted in-hospital mortality between the procedure volume groups (<50, 50–99 and ≥100) steadily decline over the years (see table 3). Figure 1A provides risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality rates allowing for comparison despite possible differences in the patient selection process and consequently the risk factor composition between hospitals in the different procedure volume groups and over time (see online supplementary tables S1–S7 for details of the process used to generate the results shown in figure 1A). These results indicate that risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality rates (1) steadily decrease over the years (annual change: −0.58 percentage points (pp), p<0.001), are (2) lower the higher the procedure volume at the hospital is (volume effect: −0.74 pp, p=0.002), but that (3) this volume effect declines over the 7-year observation period (p value of interaction term: p=0.027; annual change of volume effect: 0.2 pp).

Table 3.

Unadjusted in-hospital outcomes with regard to the performed TAVI volume of a distinct centre in a given year

| Mortality (%) | Stroke (%) | Bleeding (%) | Length of stay (mean in days) | Reimbursement (mean) | Proportion of patients with ventilation >48 hours (%) |

|

| 2008 | ||||||

| <50 procedures | 10.11 | 3.26 | 14.36 | 19.2 | 9.79 | |

| 50–99 procedures | 9.32% | 2.12 | 11.44 | 21.8 | 6.78 | |

| ≥100 procedures | 6.59 | 2.56 | 7.33 | 14.7 | 4.76 | |

| 2009 | ||||||

| <50 procedures | 9.81 | 3.57 | 14.18 | 21.6 | 9.48 | |

| 50–99 procedures | 8.36 | 3.34 | 11.25 | 18.5 | 7.14 | |

| ≥100 procedures | 6.08 | 2.12 | 7.21 | 18.0 | 7.36 | |

| 2010 | ||||||

| <50 procedures | 9.00 | 2.51 | 12.12 | 21.0 | €37 071 | 8.74 |

| 50–99 procedures | 8.11 | 2.56 | 11.41 | 19.1 | €36 173 | 8.69 |

| ≥100 procedures | 6.14 | 2.20 | 6.25 | 17.0 | €35 074 | 5.01 |

| 2011 | ||||||

| <50 procedures | 7.68 | 2.35 | 9.39 | 20.0 | €35 984 | 8.04 |

| 50–99 procedures | 8.02 | 2.35 | 9.04 | 19.3 | €35 424 | 8.28 |

| ≥100 procedures | 5.87 | 3.01 | 9.31 | 17.3 | €35 046 | 7.29 |

| 2012 | ||||||

| <50 procedures | 6.15 | 2.29 | 8.44 | 18.7 | €35 294 | 7.29 |

| 50–99 procedures | 7.07 | 2.42 | 8.41 | 18.9 | €34 798 | 5.48 |

| ≥100 procedures | 5.03 | 2.10 | 6.30 | 16.7 | €34 233 | 5.39 |

| 2013 | ||||||

| <50 procedures | 5.49 | 2.09 | 9.28 | 20.2 | €35 808 | 6.93 |

| 50–99 procedures | 5.85 | 2.33 | 6.53 | 18.2 | €34 650 | 4.56 |

| ≥100 procedures | 5.29 | 2.70 | 5.98 | 16.3 | €34 456 | 5.29 |

| 2014 | ||||||

| <50 procedures | 5.34 | 2.75 | 5.99 | 19.9 | €35 993 | 6.15 |

| 50–99 procedures | 4.58 | 2.20 | 5.73 | 18.3 | €34 904 | 4.32 |

| ≥100 procedures | 3.70 | 2.28 | 4.22 | 15.3 | €34 771 | 3.92 |

Please note that the numbers of procedures performed per year at a given centre were not constant over the observation period, so that it is possible for a centre to fall into a different volume group in a different year.

TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantations.

Figure 1.

(A-D) Risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality, stroke, bleeding and ventilation rates and their association with centre-specific procedure volumes in a given year. Estimates are based on risk-adjusted logistic regression analysis including all available patient characteristics as confounders (see table 1). Predicted probabilities are calculated by setting each confounder to its mean value (prediction at the means, see table 1 for means). Annual and volume effects were calculated using random effects meta-regression based on the estimated rates. A separate model with an interaction term was used to assess the change in the volume–outcome relationship. pp, percentage points.

Over the 7 years of data we analysed, a slight decreasing trend was visible in the risk-adjusted in-hospital stroke rate, which started out at 2%–2.5% in 2008–2009 and ranged from 1.5% to 2% in 2013–2014 (figure 1B). Volume–outcome relationship was actually negative for years following 2010, with higher volume centres having higher stroke rates.

Risk-adjusted bleeding rates (figure 1C), in contrast, showed a clear beneficial effect of higher centre procedure volumes for all years but 2011. The magnitude of the effect was distinct from 2008 to 2010 and decreased in the following years in parallel with an ongoing marked decrease in the general likelihood of bleeding complications, but still was present in 2013/2014.

For risk-adjusted in-hospital ventilation rate (>48 hours) (figure 1D), a pronounced beneficial effect of higher centre procedure volumes persisted throughout the observation period. In addition, risk-adjusted in-hospital ventilation rates decreased substantially over the years. As for bleeding, the magnitude of the volume effect was distinct in the first years but steadily declined over the 7-year period (annual change of the volume effect: 0.30 pp, p=0.041).

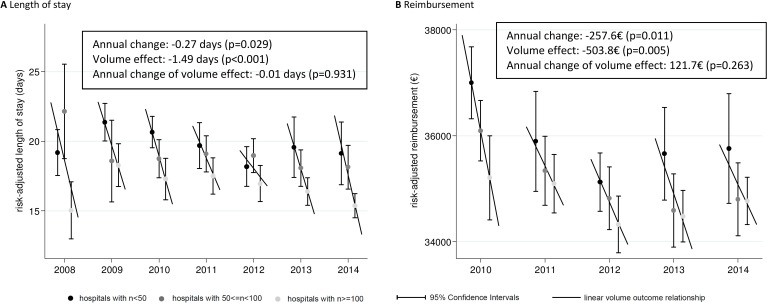

Risk-adjusted in-hospital length of stay shows a strong beneficial effect of centre procedure volume (figure 2A). Unlike the situation found for the endpoints mortality and bleeding, the magnitude of the effect did not decrease much over the observed time frame. There also is a slight reduction in average length of stay over the years.

Figure 2.

(A-B) Risk-adjusted in-hospital length of stay and reimbursement and their association with centre-specific procedure volumes in a given year. Estimates are based on risk-adjusted linear regression analyses including all available patient characteristics as confounders (see table 1). Predicted probabilities are calculated by setting each confounder to its mean value (prediction at the means, see table 1 for means). Annual and volume effects were calculated using random effects meta-regression based on the estimated means. A separate a model with an interaction term was used to assess the change in the volume–outcome relationship.

As shown in figure 2B, there is a drop in the overall reimbursement level from 2010 to 2012, but reimbursement stays roughly the same thereafter. In much the same way as found for length of hospital stay, risk-adjusted amount of reimbursement decreased only slightly over time, and showed a large volume effect which did not change over the 5-year period.

Conclusions

Our study shows mixed results regarding a volume–outcome relationship in TAVI procedures in German hospitals. First of all, TAVI-related in-hospital mortality decreased substantially between 2008 and 2014 and was lower the higher the procedure volume at the respective hospital is. The magnitude of this volume–outcome relationship, however, declines over the observation period. Especially in later years (2012–2014) differences in mortality between low, medium and high-volume centres are small.

Regarding in-hospital mortality and secondary endpoints, a volume–outcome relationship is eminent in circumstances of relatively unfavourable outcomes (see early years of mortality, bleeding and ventilation) and decreases as outcomes improve (later years of mortality, bleeding and ventilation), but is not present in circumstances of constantly low event rates (see stroke). In addition, in most of the cases when we observe a distinct annual decrease, we also observe a decreasing volume effect over time. Presumably, the small centres succeed in participating at the system-level learning curve to a degree which allows them to catch up to some degree to the group of high volume. Unfortunately, our data do not allow addressing the question whether this is due to exchange of expertise or to increasing cumulative experience. The group of small centres may also benefit from there being only a reduced capacity for improvement even in large-volume centres some years after the introduction of a new procedure.

Interestingly, decreases in the volume effect over time were not observed for the endpoints of in-hospital length of stay and reimbursement. Presumably, this might be due to the fact that high-volume centres are at a major advantage in streamlining clinical workflows before and after the procedure.

Two recent studies showed volume–outcome relationships for TAVI procedures performed in US hospitals in 2012.15 16 In both studies, patients were divided into groups of equal sample size. Disregarding the accompanying problems regarding the external validity of the results,12 13 the results shown in these studies are similar to ours: among others, inverse volume–outcome relationships were shown for the endpoints death and bleeding.15 16 One of the two studies also included the endpoints length of stay and hospitalisation costs and identified significant differences between the observed hospital volume quartiles (TAVI/year cut-offs ≤5, 6–10, 11–20 and >20).16 The other study also included the endpoint stroke and did not show significant differences between volume groups (TAVI cut-offs: 20 or 10 cases for different access routes).15

As stated before, medical authorities in several countries have issued guidelines calling for minimum numbers of procedures for primary operators performing TAVI.17–20 In Germany, such mandatory minimums are not yet implemented, but a mandatory number of 50 TAVI procedures annually is officially recommended,20 and this number is also mentioned in guidelines from the UK, Canada and Portugal.17–19 Our results confirm the existence of a volume–outcome relationship for TAVI procedures between 2008 and 2014 and these effects are in line with existing evidence from TAVI procedures performed in US hospitals.6 15 16 The above discussed weakening of the volume–outcome relationship over time, however, relativises the rationale behind mandatory minimum numbers of procedures: the volume–outcome relationship may be considerable in the years following the introduction of a new procedure when there still is a lot of room for improvement (in the two of the cited studies,15 16 ie, 2012). After a few years, then, the association between procedure numbers and better performance may diminish (see our results regarding the year 2014 and presumably thereafter). In the worst case, the volume effect is already gone by the time mandatory minimums are finally implemented, or the implementation hinders the system to reach optimal health service without restrictions. It should be, however, noted that the average number of TAVI procedures per hospital is larger in Germany compared with most other countries, and that hence the time span until such a point is reached may be longer in other countries.

This might be especially problematic since mandatory minimum quantities on the centre level are not free of further disadvantages. They are thought to lead to centralisation of procedures in large hospitals, necessitating costly patient transfers and potentially worse aftercare. In addition, it is unclear how an optimal threshold could be set (and adjusted yearly) and by whom, how effects of physician volume and hospital volume should be combined, whether low-volume hospitals and their surgeons perceive the thresholds as new incentives to operate and how new and innovative hospitals might be able to enter the market.30 The latter question is especially relevant for TAVI since a recent study showed that between 2010 and 2015 a new centre entering the TAVI market needed to perform 54 procedures to achieve clinical outcomes comparable to those reported in high-volume centres.31 According to the authors of the study, this represents more than 2 years of continuous activity.31

In addition, the question remains how to integrate the observed volume effects into the existing theory. The ‘practice-makes-perfect hypothesis’ implies a contrary causal relationship than the theory of ‘selective-referral’,7 8 and we cannot answer the question whether volume generates quality (practice makes perfect), quality generates volume (selective referral) or both.

Furthermore, Gandjour and Lauterbach differentiated the ‘practice-makes-perfect hypothesis’ into learning curve effects, economies of scope and the concept of a focused factory.32 Improved outcomes may result from economies of scale: every time doctors perform a procedure, they gain experience. Economies of scope, in contrast, would occur from the simultaneous performance of dissimilar procedures. In the TAVI context, this means that a high-volume centre might see improved TAVI outcomes as a result of the performance of high numbers of other procedures. Accordingly, Epstein already raised the question whether similar procedures should also be counted towards a set volume threshold.30 The focused factory concept, in contrast, assumes that focusing on a small number of procedures could also be favourable.32 Unfortunately, none of the existing approaches analysed whether the volume–outcome relationship differs in accordance with the number of other (closely related) procedures conducted in the respective centre.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. First of all, it is based on administrative data, and coding errors are inevitable. However, about 20% of all cardiovascular diagnosis-related groups are reviewed by independent teams of physicians on behalf of the health insurers, which should ensure a generally good reliability of the data.

Second, our risk adjustment included a number of parameters whose reliability cannot be fully secured, and we cannot guarantee that all parameters of relevance are included in the model. A major limitation is that the data source does not include information on the type of device used in individual TAVI procedures. Therefore, information regarding the type of device and access route was not used for risk adjustment. In addition, information regarding the experience of surgeons at each centre would be highly relevant for the analysis but is also unavailable.

Third, in terms of the categories used, hospital volume was classified into three fixed categories (<50, 50–99, ≥100), which is in line with thresholds mentioned in official guidelines and previously applied in the literature, but might result in possible effects related to very high volumes being hidden in the analysed group of patients treated in hospitals with ≥100 cases per year.

Lastly, the data set omits patients with a baseline diagnosis of pure aortic regurgitation, as well as those who underwent TAVI with any other concomitant cardiac procedure. This makes sense from a clinical perspective, but further complicates direct comparisons with other administrative data sets and possibly caused bias in the measurement of hospital volume and outcome.

A major strength of the study is that it provides comprehensive data on everyday TAVI practice in a large industrialised country over a multiyear period.

We conclude that the hypothesised volume–outcome relationship for TAVI exists but diminishes and may disappear over time. This should be taken into account when considering mandatory minimum thresholds.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KK and JR developed the research question and designed the methodology. VO, HR, LF, CvzM, CB, MZ and JR provided the medical knowledge of German TAVI practice informing the study design. KK defined the categories, outcomes and measures and developed and implemented the formal analysis and statistical data with support from WV and CS. KK and JR collected the data and evidence. KK, VO and WV interpreted and contextualised the results. KK and PH wrote the initial draft of the article, with JR contributing. All authors participated in the critical revision of the article and provided final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The article processing charge was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the University of Freiburg in the funding programme Open Access Publishing

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Reinöhl J, Kaier K, Reinecke H, et al. Effect of availability of transcatheter aortic-valve replacement on clinical practice. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2015;373:2438–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa1500893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gurvitch R, Tay EL, Wijesinghe N, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: lessons from the learning curve of the first 270 high-risk patients. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2011;78:977–84. 10.1002/ccd.22961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cerillo AG, Murzi M, Glauber M, et al. Quality control and the learning curve of transcatheter aortic valve implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:456 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alli OO, Booker JD, Lennon RJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:72–9. 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arai T, Lefèvre T, Hovasse T, et al. Evaluation of the learning curve for transcatheter aortic valve implantation via the transfemoral approach. Int J Cardiol 2016;203:491–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carroll JD, Vemulapalli S, Dai D, et al. Procedural experience for transcatheter aortic valve replacement and relation to outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:29–41. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaynor M, Seider H, Vogt WB. The volume–outcome effect, scale economies, and learning-by-doing. Am Econ Rev 2005;95:243–7. 10.1257/000282805774670329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luft HS, Hunt SS, Maerki SC. The volume-outcome relationship: practice-makes-perfect or selective-referral patterns? Health Serv Res 1987;22:157–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:511–20. 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shahian DM, Normand SL. The volume-outcome relationship: from Luft to Leapfrog. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1048–58. 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04308-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barker D, Rosenthal G, Cram P. Simultaneous relationships between procedure volume and mortality: do they bias studies of mortality at specialty hospitals? Health Econ 2011;20:505–18. 10.1002/hec.1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Christian CK, Gustafson ML, Betensky RA, et al. The Leapfrog volume criteria may fall short in identifying high-quality surgical centers. Ann Surg 2003;238:140–50. 10.1097/01.sla.0000089850.27592.eb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hentschker C, Mennicken R. The volume-outcome relationship and minimum volume standards--empirical evidence for Germany. Health Econ 2015;24:644–58. 10.1002/hec.3051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reames BN, Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg 2014;260:244–51. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim LK, Minutello RM, Feldman DN, et al. Association between transcatheter aortic valve implantation volume and outcomes in the United States. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:1910–5. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Badheka AO, Patel NJ, Panaich SS, et al. Effect of hospital volume on outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:587–94. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Webb J, Rodés-Cabau J, Fremes S, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement. Can J Cardiol 2012;28:520–8. 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) and the Society of Cardiothoracic Surgeons (SCTS). A position statement of the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) and the Society of Cardiothoracic Surgeons (SCTS). 2013. http://www.bcis.org.uk/resources/documents/BCIS%20SCTS%20position%20statement.pdf (cited 12 Nov 2015).

- 19. Campante Teles R, Gama Ribeiro V, Patrício L, et al. Position statement on transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol 2013;32:801–5. 10.1016/j.repc.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuck K-H, Eggebrecht H, Figulla HR, et al. Qualitätskriterien zur Durchführung der transvaskulären Aortenklappenimplantation (TAVI). Der Kardiologe 2015;9:11–26. 10.1007/s12181-014-0622-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reinöhl J, Kaier K, Reinecke H, et al. Effect of availability of transcatheter aortic-valve replacement on clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2438–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa1500893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fedeli U, Alba N, Schievano E, et al. Diffusion of good practices of care and decline of the association with case volume: the example of breast conserving surgery. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:167 10.1186/1472-6963-7-167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nguyen NT, Paya M, Stevens CM, et al. The relationship between hospital volume and outcome in bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Ann Surg 2004;240:184–92. 10.1097/01.sla.0000140752.74893.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hollenbeak CS, Rogers AM, Barrus B, et al. Surgical volume impacts bariatric surgery mortality: a case for centers of excellence. Surgery 2008;144:736–43. 10.1016/j.surg.2008.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Farley DE, Ozminkowski RJ. Volume-outcome relationships and in-hospital mortality: the effect of changes in volume over time. Med Care 1992;30:77–94. 10.1097/00005650-199201000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamilton BH, Hamilton VH. Estimating surgical volume--outcome relationships applying survival models: accounting for frailty and hospital fixed effects. Health Econ 1997;6:383–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harbord RM, Higgins JP. Meta-regression in Stata. Stata J 2008;8:493–519. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Quentin W, Geissler A, Scheller-Kreinsen D, et al. DRG-type hospital payment in Germany: The G-DRG system. Euro Obs 2010;12:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Braun JP, Bause H, Bloos F, et al. Peer reviewing critical care: a pragmatic approach to quality management. Ger Med Sci 2010;8:Doc23 10.3205/000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Epstein AM. Volume and outcome--it is time to move ahead. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1161–4. 10.1056/NEJM200204113461512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lunardi M, Pesarini G, Zivelonghi C, et al. Clinical outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation: from learning curve to proficiency. Open Heart 2016;3:e000420 10.1136/openhrt-2016-000420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gandjour A, Lauterbach KW. The practice-makes-perfect hypothesis in the context of other production concepts in health care. Am J Med Qual 2003;18:171–5. 10.1177/106286060301800407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020204supp001.pdf (133.4KB, pdf)