Abstract

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is a proinflammatory cytokine that is implicated in many autoinflammatory disorders, but is also important in defense against pathogens. Thus, there is a need to safely and effectively modulate IL-1β activity to reduce pathology while maintaining function. Gevokizumab is a potent anti–IL-1β antibody being developed as a treatment for diseases in which IL-1β has been associated with pathogenesis. Previous data indicated that gevokizumab negatively modulates IL-1β signaling through an allosteric mechanism. Because IL-1β signaling is a complex, dynamic process involving multiple components, it is important to understand the kinetics of IL-1β signaling and the impact of gevokizumab on this process. In the present study, we measured the impact of gevokizumab on the IL-1β system using Schild analysis and surface plasmon resonance studies, both of which demonstrated that gevokizumab decreases the binding affinity of IL-1β for the IL-1 receptor type I (IL-1RI) signaling receptor, but not the IL-1 counter-regulatory decoy receptor (IL-1 receptor type II). Gevokizumab inhibits both the binding of IL-1β to IL-1RI and the subsequent recruitment of IL-1 accessory protein primarily by reducing the association rates of these interactions. Based on this information and recently published structural data, we propose that gevokizumab decreases the association rate for binding of IL-1β to its receptor by altering the electrostatic surface potential of IL-1β, thus reducing the contribution of electrostatic steering to the rapid association rate. These data indicate, therefore, that gevokizumab is a unique inhibitor of IL-1β signaling that may offer an alternative to current therapies for IL-1β–associated autoinflammatory diseases.

Introduction

The interleukin-1 (IL-1) system plays a central role in the regulation of both immune and inflammatory responses (Dinarello, 1994). Initiation of signaling through this pathway occurs through interactions between the cytokines IL-1α or IL-1β and their full-length receptors, IL-1 receptor type I (IL-1RI) and the IL-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RAcP). The complex thus formed triggers recruitment of the adaptor protein MyD88 to the Toll–IL-1 receptor domains with the subsequent phosphorylation of several kinases (Weber et al., 2010). This leads to activation of genes associated with inflammation. IL-1 activity is regulated by several endogenous inhibitors, including the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), IL-1 receptor type II (IL-1RII), as well as the soluble forms of the receptors (Smith et al., 2003; Dinarello, 2011). The IL-1 pathway is highly regulated such that appropriate signaling results from a dynamic balance between these activators and inhibitors. Dysregulation of IL-1β leads to a number of systemic inflammatory diseases, including systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (Pascual et al., 2005), neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease (Lovell et al., 2005), Muckle-Wells syndrome (Hawkins et al., 2004), pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum and acne syndrome, familial Mediterranean fever, and others (Dinarello, 2005; Simon and van der Meer, 2007). Inhibition of IL-1β has been proven to be therapeutically beneficial in the treatment of a several autoinflammatory diseases (Dinarello, 2011).

In developing an optimal modulator of IL-1β for therapeutic use, it is important to take into account the roles and activities of the components of the natural regulatory system. For example, IL-1Ra is a competitive inhibitor that acts by binding to IL-1RI and preventing IL-1β binding. The soluble receptors (sIL-1RI, sIL-1RII, and sIL-1RAcP) are present in circulation and act by sequestering IL-1β, thus preventing its binding to the signaling receptor. Finally, the membrane-bound form of IL-1RII lacks an intracellular Toll–IL-1 receptor domain, and therefore acts as a decoy receptor (Mantovani et al., 2001; Bourke et al., 2003). By binding to IL-1β and allowing recruitment of IL-1RAcP into an unproductive complex, it acts as a sink to compete with the signaling receptor and removes IL-1β from circulation by receptor-mediated internalization. Overall, IL-1β signal activation depends on the distribution of the free and bound cytokine and is dynamically affected by the multiple kinetic parameters of the IL-1β interacting with its different receptors and inhibitors. Therefore, it is critical to evaluate both equilibrium and kinetic aspects of IL-1β antagonism to predict the biological response in this complex multicomponent system.

A variety of therapeutic approaches have been used that inhibit IL-1β activity at different points in the signal pathway, each with limitations based on its mechanism. These include recombinant IL-1Ra (Furst, 2004), an IL-1 binding protein based on the soluble receptors (McDermott, 2009), an anti-IL-1RI antibody that blocks IL-1β binding (Cohen et al., 2011), and an anti–IL-1β antibody that competitively blocks interaction with both IL-1RI and IL-1RII (Church and McDermott, 2009; Lachmann et al., 2009). We propose that a therapeutic agent that reduces IL-1β signaling but does not interfere with IL-1Ra or block IL-1β binding to IL-1RII or the soluble forms of the IL-1 receptors will work in concert with the natural regulatory mechanisms to efficiently regulate and clear IL-1β.

The anti–IL-1β antibody gevokizumab is a monoclonal IgG2 that inhibits IL-1β binding to its receptor via an allosteric mechanism which potently neutralizes IL-1β signal activation without affecting IL-1Ra. Gevokizumab is currently in development to address significant unmet medical needs, including noninfectious uveitis, Behçet's uveitis, cardiovascular disease, and other autoinflammatory diseases (Bhaskar et al., 2011; Gul et al., 2012). We have shown previously that gevokizumab does not block the interaction of IL-1β with the soluble receptors sIL-1RI, sIL-1RII, and sIL-1RAcP (Roell et al., 2010). Herein, we describe detailed binding parameters for the interactions that underlie the mechanistic basis for regulation of IL-1β signaling using two different methods: 1) Schild analysis with an IL-1β reporter cell line, and 2) label-free surface plasmon resonance (SPR) with purified protein components of the system. This study therefore provides new insights into both the kinetics of IL-1β interactions with its receptors as well as the mechanism by which gevokizumab inhibits IL-1β signaling via regulation of its binding kinetics to signaling components.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Recombinant Proteins.

Gevokizumab is a human engineered IgG2 κ antibody with 97% human sequence homology and affinity for IL-1β of 300 femtomolars (Owyang et al., 2011). Gevokizumab antibody binding fragment (Fab) was expressed transiently in human embryonic kidney 293E cells using the corresponding heavy chain and light chain genes encoding the Fab fragment. Control blocking antibody 5 (Ab5) is an IgG1 lambda synthesized by fusing the variable region sequences reported for a receptor-blocking antibody to the appropriate human constant regions (Roell et al., 2010). The isotype control antibody was an anti–keyhole limpet hemocyanin human IgG2 lambda antibody (clone KLH8.G2; generated at XOMA, Berkeley, CA). Recombinant human IL-1Ra, sIL-1RI, sIL-1RII, and sIL-1RAcP-Fc chimera were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Recombinant human IL-1β was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ) or R&D Systems. For biotinylation, proteins were reacted with 5- to 10-fold molar excess of NHS-PEO12-Biotin reagent (Thermo Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL) according to the vendor’s instructions. Excess free biotin was removed by centrifugation of proteins through a desalting column (Zeba Desalt Spin Column; Thermo Scientific).

Nuclear Factor-κB Cell Assay.

HeLa cells stably transfected with a nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) luciferase reporter plasmid (Biomyx, San Diego, CA) were plated in assay buffer (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s/F12 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Activity was assayed as described previously (Roell et al., 2010). In brief, for the IL-1β neutralization assay, increasing amounts of IL-1β were preincubated for 2 hours at room temperature with increasing concentrations of antagonist prior to addition to the reporter cells. IL-1β plus antagonist was incubated with the HeLa reporter cells for 16 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. To assess luciferase expression levels, Bright-Glo (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) was added to the cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and samples were read on a FlexStation 3 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). All samples were set up and assayed in duplicate or triplicate. Individual experiments were analyzed by computer-aided, nonlinear regression analysis using Prism 6.01 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Functional Data Analysis.

Equilibrium dissociation constants of sIL-1RI, sIL-1RII, IL-1Ra, and Ab5 antagonists were estimated using the method of analysis originally described by Arunlakshana and Schild (Gaddum, 1957; Arunlakshana and Schild, 1959). In this method, the term KB is used to describe this value, and is comparable to the KD value in the kinetic analysis field. Nonlinear regression using the Gaddum/Schild EC50 shift Prism model (Colquhoun, 2007) is used to determine the EC50 of IL-1β, pA2 value (the negative logarithm of the concentration of antagonist needed to shift the dose response curve by a factor of 2), Schild slope, and KB. When the Schild slope = 1, –logKB = pA2. In the case of gevokizumab, the data were fit using the Prism allosteric EC50 shift model (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002) to determine the equilibrium dissociation constant KB of gevokizumab and the value of the cooperativity factor α, the constant that quantifies the degree by which binding of gevokizumab alters the binding of IL-1β to its signaling receptor, IL-1RI.

Kinetic Analysis with SPR.

All SPR experiments were performed with triplicate injections on either Biacore2000 (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) or a multi-SPR array system ProteOn XPR36 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using a one-shot kinetics method for generating kinetic data (Bravman et al., 2006; Abdiche et al., 2011) at 25°C. The running buffer was HEPES balanced salt buffer (0.01 M HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05% Surfactant P20, 3 mM EDTA) purchased from Teknova (Hollister, CA) and supplemented with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Immobilization of either IL-1β or sIL-1RI molecules via amine coupling to sensor chip causes heterogeneous binding and a significant loss of activity in the case of IL-1β (data not shown). To minimize heterogeneity on sIL-1RI, a second approach to determine the kinetic and affinity parameters of the interaction between IL-1β and sIL-1RI in the presence or absence of gevokizumab was used using capture via biotin-NeutrAvidin (Thermo Scientific). NeutrAvidin was immobilized at high density (≥6000 response units) to an activated sensor chip surface using ethyl(dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide (EDC/NHS) chemistry according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Different levels of biotinylated sIL-1RI were then captured on different flow channels. Reference channels were prepared similarly, except that no protein was captured. Five concentrations of IL-1β (between 50 and 0.1 nM) in 3-fold serial dilutions in addition to a buffer blank were injected at a flow rate of 30 μl/min over each surface simultaneously (ProteOn XPR36) and in random sequence (Biacore 2000) for 2–4 minutes followed by a 5–10-minute dissociation in running buffer. Between each injection, the signal was allowed to decay to baseline so that no regeneration step was required. Alternatively, faster regeneration of sIL-1RI was achieved by using two 20-second pulses of 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5, at 100 μl/min. Data were double referenced by subtracting the signal obtained from buffer injections and the reference flow channel. A mass transport test indicated that this system was affected by mass transport (data not shown). Accordingly, the data were fit globally using a simple 1:1 binding model (1:1 Langmuir) that incorporates a mass transport component using Scrubber2 software (BioLogic Software, Campbell, Australia) to yield association (ka) and dissociation (kd) rate constants and affinity KD= kd / ka. Constants were calculated for each individual experiment, and these values were used to calculate the averages and standard deviations. To examine the influence of gevokizumab (or its Fab fragment) on IL-1β binding to the IL-1RI receptor, IL-1β was injected in the presence of at least 10-fold molar excess (0.5–1 μM) of gevokizumab to ensure full saturation of IL-1β and to minimize avidity effects due to binding of IL-1β to both arms of gevokizumab. Despite these procedures, and particularly in the case of the bivalent gevokizumab antibody, the binding of the IL-1β-gevokizumab complex to immobilized sIL-1RI was significantly impacted by avidity and rebinding effects. Thus, only low-density surfaces (≤50 RU) of biotinylated sIL-1RI were used to accurately determine the kinetic parameters of the binding of this complex to sIL-1RI. Analyte samples of IL-1β precomplexed with either gevokizumab IgG2 or Fab were serially diluted in running buffer and injected at a flow rate of 30 μl/min for 2–3 minutes followed by 5–10-minute dissociation in running buffer. Surfaces were regenerated as described earlier. Similarly, data were double referenced and fit as described earlier to yield ka, kd, and KD.

Similarly to sIL-1RI, sIL-1RII was immobilized via amine coupling or capture via NeutrAvidin to the SPR sensor surface. In contrast to sIL-1RI, however, the kinetics of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RII using both methods were nearly identical. The same experimental setup previously outlined was used for sIL-1RII kinetics, except that higher concentrations of IL-1β were used and the receptor was regenerated using two 20-second pulses of 3 M MgCl2 solution at 100 μl/min. The data were fit as described to yield ka, kd, and KD.

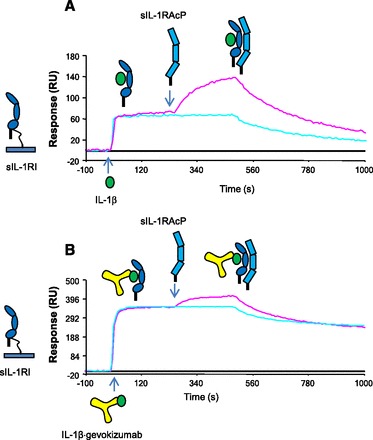

An additional SPR format was used to characterize the influence of gevokizumab on IL-1β binding to IL-1 receptors. In brief, biotinylated gevokizumab was captured via NeutrAvidin on to the SPR sensor surface and followed by a 100 nM injection of IL-1β, which was expected to saturate all gevokizumab binding sites. Due to the very high affinity interaction between gevokizumab and IL-1β and the slow dissociation rate of these molecules (Owyang et al., 2011), the complex was expected to be stable over the duration of the assay, and thus the dissociation observed in the assay reflects dissociation of the receptor from the complex of gevokizumab and IL-1β. Samples of sIL-1RI or sIL-1RII were prepared at final concentrations of (1.2, 3.7, 11, 33, and 100 nM) and (3.7, 11, 33, 100, and 300 nM), respectively, and injected at 30 μl/min randomly (Biacore 2000) or simultaneously (ProteOn XPR36) (Bravman et al., 2006; Abdiche et al., 2011) over IL-1β·gevokizumab or unoccupied gevokizumab surfaces for 2–3 minutes. Dissociation was monitored for 5–10 minutes, and surfaces were regenerated as described earlier (50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5 or 3 M MgCl2 for sIL-1RI or sIL-1RII, respectively). Buffer was injected separately or alongside the other samples to provide an internal blank for double referencing purposes. The ability of receptors to inhibit IL-1β binding to gevokizumab was assessed using the same format, except that IL-1β was injected alone or in combinations of 5-fold molar excess of receptors using the “co-inject” mode of the ProteOn instrument at 30 μl/min. This injection mode consisted of two injections drawn in sequence from separate wells, and then injected consecutively over the chip surface with no running buffer flow in between. The first injection of 240 seconds contained a dilution series of IL-1β (0.4, 1.22, 3.7, 11, and 33 nM) alone or in combination with 165 nM sIL-1RI or sIL-1RII. The second injection lasting 360 seconds contained buffer or the same concentration of sIL-1RI or sIL-1RII. Buffer was injected along the flow channel to provide a blank for double referencing purposes.

Binding of sIL-1RAcP to sIL-1RI·IL-1β or sIL-1RI·IL-1β·gevokizumab complexes was performed as described previously (Roell et al., 2010).

Results

Investigation of Gevokizumab Activity by Schild Analysis with Cultured Cells

Characterization of Gevokizumab’s Mode of Antagonism of IL-1β–Mediated Signaling.

Gevokizumab has been shown to inhibit IL-1β–mediated signaling in functional cell-based assays, resulting in a 20- to 100-fold right shift of the IL-1β dose-response curves, with the inhibition of signaling surmountable at high IL-1β concentrations (Roell et al., 2010). This observation, in conjunction with the observation that gevokizumab did not block the assembly of the IL-1β signaling complex in biophysical studies, suggested that gevokizumab inhibits IL-1β signaling via an allosteric mechanism. We applied Schild analysis to further study the mechanism of gevokizumab’s negative allosteric modulation and to quantify the parameters of modulation. For these studies, we used a NF-κB reporter cell line that is responsive to IL-1β. The inhibitory effects of gevokizumab were also compared with two other antagonists of IL-1β signaling: the competitive antagonistic ligand IL-1Ra and an orthosteric anti–IL-1β antagonist antibody (Ab5) (Roell et al., 2010).

Increasing concentrations of both IL-1Ra and Ab5 produced concentration-dependent, parallel, rightward shifts in the IL-1β concentration-response curve with no diminution of maximal responses (Fig. 1, A and B). This pattern is indicative of surmountable competitive antagonism. Analysis of the data according to the Gaddum/Schild EC50 shift model yielded Schild slopes close to unity (slope = 1 for IL-1Ra and slope = 0.9 for Ab5); constraining them as such yielded pA2 values (mean ± S.D., n = 3) of 10.22 ± 0.3 for IL-1Ra and 10.6 ± 0.22 for Ab5. The estimated equilibrium dissociation constants KB (−logKB = pA2 when the Schild slope = 1) for the binding of IL-1Ra and Ab-5 to their respective binding partners (IL-1RI and IL-1β) were 45 ± 15 and 23 ± 13 pM, respectively (mean ± S.D., n = 3). These values are similar to the affinity values we determined by SPR for Ab5 (KD = 30 pM, data not shown) and to previously published values of IL1Ra (39 pM, Fredericks et al., 2004). This Schild analysis is consistent with previous characterizations of these IL-1β antagonists as competitive inhibitors of IL-1β signal activation (Arend et al., 1998) and provides a frame of reference for comparison of the mechanism of gevokizumab inhibition.

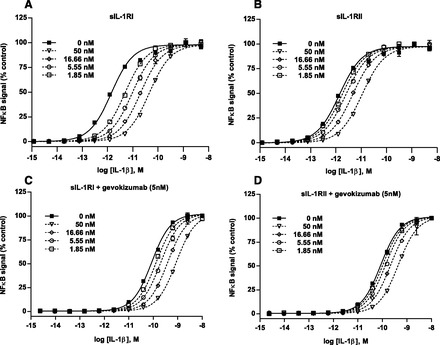

Fig. 1.

Schild analysis of inhibition of IL-1β–mediated NF-κB activation by gevokizumab and other inhibitors. (A–C) Effect of increasing concentrations (dashed lines) of IL-1Ra (A), Ab5 (B), or gevokizumab (C) on IL-1β–induced NF-κB activation via its binding to IL-1RI. Each panel shows a representative experiment for each inhibitor. All measurements were normalized as percentage of maximum response. (A and B) Neutralization of IL-1β functional activity by both IL-1Ra (binding to IL-1RI) and Ab5 (binding to IL-1β) was consistent with competitive inhibition. The curves superimposed on the data represent the best global nonlinear regression fit of a competitive Schild model. These control experiments for comparison with gevokizumab were carried out three times. Points and error bars represent the mean and range of duplicate measurements. (C) Modulation by gevokizumab (binding to IL-1β) was consistent with allosteric inhibition. The curves superimposed on the data represent the best global nonlinear regression fit of an allosteric EC50 shift model. Points represent the mean and SEM of triplicate measurements of a representative of three experiments.

Schild analysis of gevokizumab data also revealed a parallel shift in the IL-1β concentration-response curve with no diminution of the maximum signal that was surmountable with increasing concentrations of IL-1β (Fig. 1C). In contrast to the aforementioned competitive antagonists, however, the displacement of the IL-1β concentration response reached a limiting value. The Schild regression slope differed significantly from 1.0, indicating surmountable allosteric inhibition (Kenakin, 2009). The data were therefore fit to the allosteric EC50 shift model (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002) and yielded an average KB value (mean ± S.D., n = 3) of 4.8 ± 4.4 pM and a cooperativity factor α of 0.032 ± 0.001 for the modulation by gevokizumab of IL-1β action on the IL-1R signaling. Thus, the neutralization of IL-1β by gevokizumab is consistent with an allosteric mechanism, primarily modulating the affinity of IL-1β and its signaling receptor for each other by a factor of 32.

The Impact of Gevokizumab on the Inhibitory Effects Mediated by the Soluble Receptors sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII.

In vivo, gevokizumab could potentially impact the negative regulation of IL-1β signaling by the two circulating soluble IL-1 receptors, sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII. First, we used Schild analysis in the absence of gevokizumab to quantitate the inhibition parameters (pA2 and KB) for the soluble IL-1 receptors. We incubated cells with increasing concentrations of IL-1β and five concentrations of either soluble sIL-1RI or sIL-1RII. This analysis confirmed that both of the soluble receptors antagonize IL-1β–induced NF-κB activation as illustrated by parallel right shifts in IL-1β dose-response curves (Fig. 2, A and B). The Schild analysis yielded binding affinity values (KB) for IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII of 0.8 ± 0.3 and 3.5 ± 2 nM (mean ± S.D.), respectively. This difference in binding affinity was not significant by t test.

Fig. 2.

The impact of gevokizumab on the inhibitory effects of IL-1β–mediated NF-κB activation caused by the soluble receptors, sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII. (A and B) Effect of increasing concentrations (dashed lines) of either sIL-1RI (A) or sIL-1RII (B) on IL-1β–induced NF-κB activation. (C and D) Effect of increasing concentrations (dashed lines) of either sIL-1RI (C) or sIL-1RII (D) on IL-1β–induced NF-κB activation in the presence of a saturating concentration of gevokizumab. The curves superimposed on the data represent the best global nonlinear regression fit of a competitive Schild model. All measurements were normalized as percentage of maximum response. Points represent either single measurements or the mean and range of duplicate measurements for a representative experiment (n = 3).

Next, we investigated the effects of gevokizumab on these two soluble receptor inhibitors. Gevokizumab was added at 5 nM, a saturating concentration which was shown to induce the maximal right shift in the IL-1β dose-response curve (Fig. 1C). In the presence of gevokizumab, both receptors still induced right shifts to the IL-1β dose-response curves (Fig. 2, C and D). However, the Schild analyses revealed that gevokizumab had a significant impact on the inhibition by sIL-1RI (t test, P = 0.006) as observed by a 4-fold change in the affinity of sIL-1RI for IL-1β (KB = 3.3 ± 0.8 nM, mean ± S.D.). In contrast, there was no significant change in the affinity of sIL-1RII for IL-1β (KB = 4.1 ± 0.7 nM, mean ± S.D.). These data indicate that gevokizumab is a selective negative allosteric modulator which reduces the binding affinity of sIL-1RI to IL-1β.

Kinetic Studies of Gevokizumab Impact on the IL-1β Signaling System Using Purified IL-1β Signaling Components

The Effect of Gevokizumab on the Association Rate of IL-1β Binding to sIL-1RI.

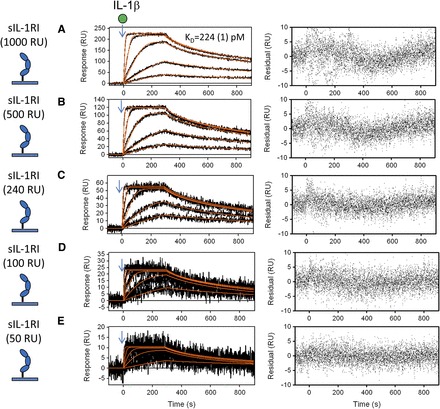

To understand the molecular mechanism of IL-1β inhibition by gevokizumab, we used SPR to determine the impact of this antibody on the binding kinetics of IL-1β to the main purified components of the IL-1β signaling system. First, we determined the kinetics and binding affinity of IL-1β interaction with the sIL-1RI immobilized to biosensor chips. We analyzed sensorgrams of injections of five concentrations of IL-1β over five different surface densities of sIL-1RI (Fig. 3). The data were globally fit with a simple binding model (1:1 Langmuir) incorporating a mass transfer component (Glaser, 1993; Myszka et al., 1998; Kortt et al., 1999). This analysis yielded an association rate constant (ka) (mean ± S.D.) of 1.19 ± 0.44 × 107 M−1 s−1 and a dissociation rate constant (kd) (mean ± S.D.) of 4.6 ± 2 × 10−3 s−1 (Table 1). The red lines (Fig. 3, A–E, left panel) represent the best global fit which overlapped the response data over the entire time course of binding as judged by the low and randomly scattered residuals that had an amplitude comparable to instrument noise (approximately ± 4 RU) (Fig. 3, A–E, right panel). The equilibrium dissociation constant KD value (mean ± S.D.) derived from multiple measurements using various surface densities was 0.39 ± 0.12 nM (Table 1). These binding affinity parameters are in agreement with measurements previously reported for this interaction determined using a variety of cell-based assays (McMahan et al., 1991; Liu et al., 1996).

Fig. 3.

Global kinetic analysis of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI immobilized to a biosensor surface. Binding of increasing concentrations of IL-1β (0.6, 1.8, 5.5, 16.6, and 50 nM) to various densities of captured sIL-1RI (50–1000 RU). sIL-1RI was captured at decreasing densities, resulting in maximal IL-1β binding capacity (Rmax) values of 227 (A), 120 (B), 55 (C), 23 (D), and 11 RU (E). The black lines represent the measured data and the red lines represent the global fits to a simple 1:1 model (1:1 Langmuir) including the mass transport parameter using Scrubber2 software (BioLogic Software); the residuals are shown for each overlay plot. The KD value derived from global fit of a single binding experiment is denoted with the fitting error shown in parenthesis. All KD values (Table 1) are averages of multiple independent measurements using various surface densities (n = 7).

TABLE 1.

Effect of gevokizumab on kinetic parameters of IL-1β binding by SPR

The values for kinetic parameters and affinity in this table represent the mean and S.D. for the number of experiments indicated in each row.

| Immobilized Ligand | Binding Interaction | ka | kd | KD | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-1s−1 | s−1 | nM | |||

| sIL-1RI | sIL-1RI + IL-1β ↔ IL-1β·sIL-1RI | (1.2 ± 0.4) × 107 | (4.6 ± 2) × 10−3 | 0.39 ± 0.12 | 7 |

| sIL-1RI + IL-1β·gevokizumab ↔ IL-1β·gevokizumab·sIL-1RI | (1.2 ± 0.3) × 106 | (5.7 ± 1.3) × 10−3 | 4.8 ± 2.4 | 5 | |

| sIL-1RI + IL-1β·gevokizumab Fab ↔ IL-1β·gevokizumab Fab·sIL-1RI | (1.9 ± 0.3) × 106 | (6.6 ± 0.8) × 10−3 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 3 | |

| Gevokizumab·IL-1β | IL-1β·gevokizumab + sIL-1RI ↔ IL-1β·gevokizumab·sIL-1RI | (0.7 ± 0.3) × 106 | (8.0 ± 0.7) × 10−3 | 11 ± 4 | 3 |

| sIL-1RII | sIL-1RII + IL-1β ↔ IL-1β·sIL-1RII | (4.8 ± 2.9) × 104 | (1.4 ± 0.3) × 10−4 | 3.8 ± 2.5 | 5 |

| sIL-1RII + IL-1β·gevokizumab ↔ IL-1β·gevokizumab·sIL-1RII | (1.3 ± 0.4) × 104 | (2.1 ± 3) × 10−4 | 8.8 ± 3.5 | 5 | |

| sIL-1RII + IL-1β·gevokizumab Fab ↔ IL-1β·gevokizumab Fab·sIL-1RII | (2 ± 0.1) × 104 | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 10−4 | 6 ± 0.37 | 2 | |

| Gevokizumab·IL-1β | IL-1β·gevokizumab + sIL-1RII ↔ IL-1β·gevokizumab·sIL-1RII | (7.9 ± 1.9) × 104 | (7.2 ± 2.1) × 10−5 | 1.8 ± 1 | 3 |

| Gevokizumab | Gevokizumab + IL-1β ↔ gevokizumab·IL-1β | (5.6 ± 3) × 105 | (4.41 ± 2) × 10−6 | ≤7.3 ± 3.7a | 2 |

| Gevokizumab + IL-1β·sIL-1RI ↔ gevokizumab·IL-1β·sIL-1RI | (1.8 ± 0.2) × 105 | (3.7 ± 0.7) × 10−6 | ≤17 ± 2.7a | 2 | |

| Gevokizumab + IL-1β·sIL-1RII ↔ gevokizumab–IL-1β·sIL-1RII | (4.4 ± 1) × 105 | (5.0 ± 2) × 10−6 | ≤13 ± 2.1a | 2 | |

| sIL-1RAcP | sIL-1RAcP + IL-1β·sIL-1RI ↔ sIL-1RAcP·IL-1β·sIL-1RI | (1.6 ± 0.22) × 105 | (4.0 ± 0.3) × 10−4 | 25 ± 3 | 3 |

| sIL-1RAcP + IL-1β·gevokizumab·sIL-1RI ↔ sIL-1RAcP·IL-1β·gevokizumab·sIL-1RI | (0.8 ± 0.03) × 105 | (6.6 ± 1.5) × 10−3 | 76.6 ± 15 | 3 |

The kinetics of the interaction between gevokizumab and IL-1β, IL-1β·sIL-1RI, or IL-1β·sIL-1RII are at the limit of measurement by SPR, and therefore the KD values in this table represent upper limits of KD (i.e., lower limits of affinity).

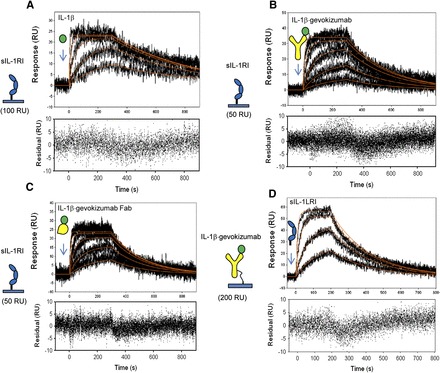

Gevokizumab significantly reduced the affinity of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI (4.8 ± 2 nM) (mean ± S.D., P = 0.00057 by t test; Fig. 4, A and B; Table 1). The primary effect of gevokizumab was to slow the observed association rate constant of IL-1β for sIL-1RI by 10-fold from 1.19 ± 0.44 × 107 to 1.21 ± 0.3 × 106 M-1s−1 (mean ± S.D.). Under these assay conditions, gevokizumab had no detectable impact on the dissociation rate constant of IL-1β from sIL-1RI. Similarly, the Fab fragment of gevokizumab decreased the association rate to a comparable extent (ka = 1.9 ± 0.3 × 106 M−1 s−1, P = 0.0029 by t test) and did not impact the dissociation rate (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Effect of gevokizumab on the kinetics of IL-1β binding to immobilized sIL-1RI. (A) Binding of IL-1β to low-density sIL-1RI captured on a biosensor surface (100 RU) in the absence of gevokizumab. (B and C) Binding of IL-1β preincubated with saturating concentrations of either gevokizumab (B) or gevokizumab Fab (C) to low densities of sIL-1RI (50 RU). The black lines represent the measured data and red curves represent the best fit of the binding response to a simple 1:1 binding model (1:1 Langmuir) using Scrubber2 software. (D) Binding of sIL-1RI to immobilized gevokizumab precomplexed with IL-1β. Binding curves (black lines) for each of the sIL-1RI concentrations are shown. Red curves represent the best fit of the binding response to a simple 1:1 binding model (1:1 Langmuir) using Scrubber2 software. Residuals are shown below each overlay plot.

To confirm that the kinetic parameters for IL-1β–gevokizumab binding to sIL-1RI were not affected by immobilization of the receptor to the biosensor surfaces, an alternate SPR format was used. In this assay, gevokizumab was immobilized and used to capture IL-1β. The binding kinetics of sIL-1RI to the captured IL-1β were measured (Fig. 4D; Table 1). Although the assay format did not allow for a direct comparison of receptor binding to IL-1β in the absence of gevokizumab, the kinetics of sIL-1RI binding to immobilized IL-1β·gevokizumab complexes were comparable to those determined with the prior assay format. Thus, these SPR studies conducted in both formats demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of gevokizumab on the binding of IL-1β to sIL-1RI was due primarily to a slowing of the association rate of this interaction.

Gevokizumab Does Not Impact Kinetics of IL-1β Binding to Soluble IL-1RII.

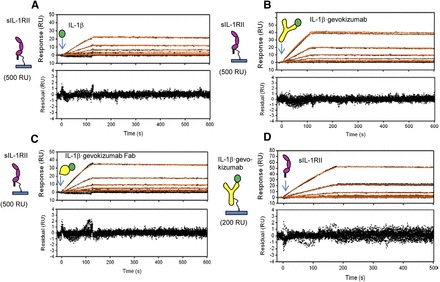

We next assessed the influence of gevokizumab on IL-1β binding to the soluble form of the decoy receptor, sIL-1RII, immobilized on biosensor chips. To study this interaction, we first quantitated the kinetic parameters for IL-1β binding to sIL-1RII. The observed association rate constant for IL-1β binding to sIL-1RII was ∼300-fold slower than that observed for IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI (Fig. 5A; Table 1), and the rate of dissociation of IL-1β from sIL-1RII was ∼30-fold slower than that of IL-1β from sIL-1RI. In contrast to its large impact on the association rate of IL-1β to sIL-1RI, neither gevokizumab nor its Fab fragment reduced the association rate constant of IL-1β to sIL-1RII by more than 2-fold (Fig. 5, B and C; Table 1). Moreover, gevokizumab had no impact on the rate of dissociation of IL-1β from sIL-1RII.

Fig. 5.

Effect of gevokizumab on the kinetics of IL-1β binding to immobilized sIL-1RII. (A) Increasing concentrations of IL-1β (1.9, 3.9, 7.8, 15.6, 31.2, and 62.5 nM) were injected over immobilized sIL-1RII. Representative binding curves (black lines) for each of the IL-1β concentrations are shown. Red curves represent the best fit of the binding response to a simple 1:1 binding model (1:1 Langmuir) using Scrubber2 software. (B and C) Same experimental setup outlined in (A) but with IL-1β precomplexed with saturating concentrations of either gevokizumab (B) or gevokizumab Fab (C). Red curves represent the best fit of the binding response to a simple 1:1 binding model (1:1 Langmuir) using Scrubber2 software. (D) Binding of increasing concentrations of sIL-1RII (3.7, 11.1, 33.3, 100, and 300 nM) to immobilized gevokizumab precomplexed with IL-1β. Representative binding curves (black lines) for each of the sIL-1RII concentrations are shown. Red curves represent the best fit of the binding response to a simple 1:1 binding model (1:1 Langmuir) using Scrubber2 software. Residuals are shown below each overlay plot.

To confirm that the binding kinetics measured for IL-1β and sIL-1RII were not affected by immobilization of the receptor to the biosensor surfaces, an alternate SPR format was used in which IL-1β was captured by immobilized gevokizumab, as described for sIL-1RI earlier. Consistent with the aforementioned results, this SPR assay format yielded similar kinetic parameters, indicating a lack of effect of the antibody on IL-1β binding to sIL-1RII (Fig. 5D; Table 1).

Influence of sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII Receptors on IL-1β Binding to Gevokizumab.

The principle of allosteric linkage (Gregory et al., 2007; Wyman and Gill, 1990) requires that allosteric inhibition be reciprocal. Thus, this principle predicts that the binding of sIL-1RI to IL-1β should inhibit the binding of the cytokine to gevokizumab. Accordingly, this same type of reciprocal inhibition should be exhibited by sIL-1RII, although to a lesser extent. To explore whether the binding of sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII receptors to IL-1β could allosterically alter the binding of IL-1β to gevokizumab, we immobilized the antibody to biosensor chips and injected IL-1β in the presence or absence of soluble receptors (Fig. 6). In the absence of the soluble receptors, the dissociation rate of IL-1β from gevokizumab approached the limit of SPR quantitation (10−6 s−1) in the 4000-second dissociation time course used. Taking into account this limitation, the off-rate of IL-1β from gevokizumab was estimated to be ≤3.9 × 10−6 s−1 (Supplemental Fig. 1). This result is consistent with a previously published analysis of this interaction (Owyang et al., 2011).

Fig. 6.

Reciprocal relationship between inhibition of IL-1β·receptor binding by gevokizumab and inhibition of IL-1β·gevokizumab binding by receptors. (A) Short time-course kinetics of IL-1β binding to captured gevokizumab. The kinetic data were fit with Scrubber2 software using a simple 1:1 Langmuir binding model. For the curve fit, the fixed off-rate obtained from the long time-course dissociation kinetics (Supplemental Fig. 1) was used (3.9 × 10−6). The fit of the data are shown as a solid red line (n = 2). (B and C) Kinetic parameters of preformed IL-1β·receptor complex binding to captured gevokizumab antibody using sequential step injections (coinject mode). To perform the sequential injections, preformed complexes of IL-1β (33, 11, 3.66, 1.22, and 0.4 nM) combined with 5 molar excess of either sIL-1RI (B) or sIL-1RII (C) were first injected followed by a second injection of buffer containing the same concentration of receptors only. Binding curves (black lines) for each of the IL-1β·receptor concentrations are shown. Red curves represent the best fit of the binding response to a simple 1:1 binding model (1:1 Langmuir) using Scrubber2 software. Residuals are shown below each overlay plot.

Because of the limitations of the assay with respect to measuring changes in the dissociation rate, the effects of sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII on the association kinetics of IL-1β binding to gevokizumab were the focus of the initial studies. In these assays, a sequential injection method using the “co-inject” mode of the SPR instrument was used. During the association phase, IL-1β combined with 5-fold molar excess of either sIL-1RI or sIL-1RII was injected. For the dissociation phase, buffer containing the same concentration of either sIL-1RI or sIL-1RII was injected to maintain saturation of IL-1β with receptor and ensure that the observed kinetics only resulted from the dissociation of IL-1β from gevokizumab.

Comparison of association rates of IL-1β in the presence and absence of sIL-1RI (Fig. 6, A and B) shows that the observed association rate constant was 5-fold slower in presence of sIL-1RI. In contrast, the presence of a saturating amount of sIL-1RII (Fig. 6C) decreased the association rate constant of IL-1β for gevokizumab to a lesser extent (<2-fold).

To better assess the impact of sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII on the dissociation of IL-1β from gevokizumab, additional SPR kinetic experiments were conducted with a 3-hour dissociation time course (Supplemental Fig. 2, A–C). In these assays, the running buffer contained 5-fold molar excess of either sIL-1RI or sIL-1RII to maintain saturating concentrations of the soluble receptors. In this assay, no apparent effect was seen on the off-rate but, as observed in the shorter time course assays, the association rates of IL-1β to gevokizumab decreased significantly in the presence of saturating sIL-1RI (P = 0.022 by t test) and to a much lesser extent with sIL-1RII (not significant). These results indicate that sIL-1RI inhibits IL-1β binding to gevokizumab primarily by slowing the association rate, and that sIL-1RII does not have a large impact on the binding of the cytokine to the antibody (Table 1).

Gevokizumab Decreases Kinetics and Affinity IL-1β·sIL-1RI Binary Complex Binding to sIL-1RAcP.

The binding of IL-1β to IL-1RI initiates the subsequent binding of IL-1RAcP to form a ternary signaling complex (IL-1RI·IL-1β·IL-1RAcP). Our prior SPR study suggested that the assembly of the ternary IL-1β receptor complex occurs in a stepwise manner in the presence and absence of gevokizumab (Roell et al., 2010). In that study, we immobilized gevokizumab on the biosensor surface. In the present study, we used an alternate assay format where sIL-1R was immobilized on the biosensor surface. Initially, we injected IL-1β alone followed by an injection of sIL-1RAcP. Next, we injected IL-1β in complex with gevokizumab followed by an injection of sIL-1RAcP (Fig. 7, A and B). The increase in response (RU) resulting from sIL-1RAcP binding was approximately 60 RUs in the absence and presence of gevokizumab. This result confirmed our previous observation that gevokizumab does not prevent the formation of the ternary complex. However, gevokizumab was shown to impact the affinity of sIL-1RAcP binding to the sIL-1RI·IL-1β binary complex (Roell et al., 2010).

Fig. 7.

Effect of gevokizumab on the formation of the IL-1β·sIL-1RI·sIL-1RAcP complex. (A) sIL-1RI was initially immobilized on the biosensor surface; IL-1β (50 nM) was injected next followed by a second injection of either running buffer or sIL-1RAcP (100 nM). (B) Same experimental setup as outlined in (A) except IL-1β was prebound to gevokizumab.

To assess the impact of gevokizumab on the kinetics of the formation of the ternary complex, kinetic analyses of sIL-1RI·IL-1β binary complex binding to immobilized sIL-1RAcP were conducted in the presence and absence of the antibody, as described previously (Roell et al., 2010) (Supplemental Fig. 3; Table 1). A 1.9-fold reduction in the association rate constant (1.63 ± 0.22 × 105 vs. 8.52 ± 0.27 × 104 M−1 s−1, mean ± S.D.) and a 1.6-fold increase in the dissociation rate constant were observed for sIL-1RAcP binding in the presence of gevokizumab. The changes to the kinetic parameters in the presence of gevokizumab resulted in a 3-fold decrease in binding affinity (KD) for this interaction. Taking into account the observed reduction in the binding affinity of IL-1β for sIL-1RI (10-fold), the subsequent inhibition of sIL-1RAcP resulted in a total affinity reduction of 30-fold. Thus, gevokizumab affects signaling by negatively modulating both the affinity of Il-1β binding to IL-RI and the subsequent binding of IL-1RAcP to the signaling complex.

Discussion

In the present study, we present a detailed kinetic analysis of the influence of gevokizumab on IL-1β binding to its receptors in vitro. Because all nucleated cells express IL-1 receptors, and soluble receptors are present at relatively high concentrations in the circulation (Mantovani et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2003), it is unlikely that the interactions of IL-1β with its binding partners ever reach equilibrium. Instead, IL-1β release and clearance are a dynamic and rapid process, and thus, binding kinetics are as important as equilibrium parameters in regulating IL-1β signaling in vivo. Therefore, we used both Schild analyses with cultured cells and SPR-based kinetic studies with purified components to measure the effect of gevokizumab on the binding of IL-1β to its receptors. Both studies demonstrated that gevokizumab decreases the binding affinity of IL-1β for its signaling receptor, IL-1RI, and the subsequent binding of IL-1RAcP, resulting in an approximately 30-fold reduction in both binding and signaling. Also, these studies demonstrated that gevokizumab has little to no effect on the binding affinity of IL-1β for the soluble form of the decoy receptor, sIL-1RII.

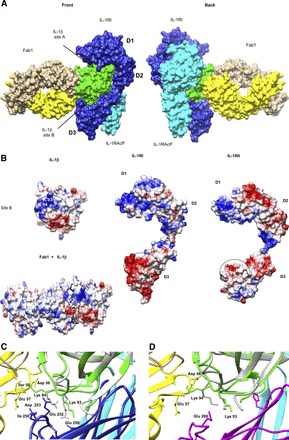

In addition to comparing gevokizumab’s effect on two different receptors, we also compared it to two competitive inhibitors of IL-1 signaling, IL-1Ra and an anti–IL-1β antibody (Ab5). Schild analysis revealed that both of these inhibitors, unlike gevokizumab, behave as classic orthosteric inhibitors. Key amino acids involved in the contacts between IL-1β and gevokizumab were previously identified by mutational analysis and found to be outside of the receptor binding region of IL-1β (Owyang et al., 2011), leading to the suggestion that the binding epitope for gevokizumab was allosteric. This hypothesis was confirmed by the X-ray crystal structure of a Fab fragment based on the gevokizumab variable region sequence (Fab1) complexed to human IL-1β (Blech et al., 2013) (Fig. 8A). Blech et al. also determined the crystal structure of a Fab fragment of canakinumab (from which the sequence of Ab5 was derived) in complex with IL-1β, in which they verified that the epitope for canakinumab overlaps the receptor binding region, consistent with its behavior as a competitive antagonist of IL-1β.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representations of IL-1β binding to Fab1 (based on gevokizumab sequences) and the interactions of this complex with both IL-1RI and IL-1RII receptors. (A) Surface representation of the superimposed IL-1β·Fab1 structure (Protein Data Bank code 4GTM) onto the IL-1β·IL-1RI·IL-1RAcP ternary complex (Protein Data Bank code 4DEP). Alignment was based on the IL-1β molecules from both complexes. Depicted are two rotated views (back and front). IL-1β from 4GTM is colored in green, Fab1 heavy chain in yellow, Fab1 light chain in sandy brown, sIL-1RI in blue, and IL-1RAcP in cyan. D1, D2, and D3 are the immunoglobulin-like domains of sIL-1RI. Sites A and B of IL-1β are also indicated. (B) The electrostatic potential surface representations of IL-1β, Fab1 in complex with IL-1β, IL-1RI, and IL-1RII-free receptors. Site B of IL-1β and D3 domains of IL-1RI and IL-1RII involved in binding interaction are highlighted with circles. (C and D) Close-up views of the binding interfaces between IL-1β·Fab1 and between IL-1β·IL-1RI·IL-1RAcP (C) or IL-1β·IL-1RII·IL-1RAcP (D), aligned using UCSF Chimera software (Pettersen et al., 2004), showing details of these interactions. The IL-1β molecule bound to Fab1 is shown in green, and the IL-1β molecules bound to the receptors are shown in gray. The other molecules are colored as described earlier. Key contact residues are indicated, including lysine 94 in IL-1β that is contacted by both Fab1 and IL-1RI receptor in their separate complexes. The D3 domain of IL-1RII receptor (magenta) has less contact with IL-1β and is extended away from the binding interface of IL-1β·Fab1, in contrast to that of IL-1RI, which has more extensive contact and folds up over the side chain of Lys93.

To understand the mechanistic basis of the observed decrease in ligand/receptor affinity mediated by gevokizumab binding, we investigated the kinetics of IL-1β binding to its receptors in the presence and absence of this antibody. SPR analysis of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI demonstrated that the association rate is very rapid, approaching 107 M−1 s−1. Evaluation of the surface electrostatic potentials of IL-1β and IL-1RI leads us to propose that the rapid association kinetics of this interaction are being driven by electrostatic steering (described later). The dissociation rate also is rapid, resulting in an equilibrium affinity in the low nanomolar range for this interaction. This property of IL-1RI makes IL-1β a very potent cytokine that can efficiently act locally at picomolar and femtomolar concentrations.

Because efficient removal of excess cytokines is important for the regulation of their signaling, especially with a very potent cytokine such as IL-1β, we also determined the kinetic parameters of IL-1β binding to its decoy receptor sIL-1RII, which plays a major role in IL-1β clearance. Analysis of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RII also demonstrated a nanomolar affinity, which is consistent with previous reports (Symons et al., 1995; Smith et al., 2003). The association rate constant for IL-1β binding to sIL-1RII is notably slower (104 M−1 s−1) than its binding to sIL-1RI. However, the equilibrium binding constant is comparable to that of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI because the slower association rate is accompanied by a slower dissociation rate. This property of sIL-1RII, together with its relatively higher concentration in the circulation, makes this negative regulator an “ideal” sink for IL-1β. The difference between binding kinetics for sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII is not completely surprising given that the extracellular domains of these receptors share only 28% amino acid homology. The difference between the association rates of IL-1β binding to the signaling and decoy receptors is likely to be an important property that contributes to the physiological regulation of IL-1β activity.

Our current study shows that gevokizumab reduces the affinity of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI by 10-fold and subsequent binding of sIL-1RAcP by another 2- to 3-fold, as previously suggested (Roell et al., 2010). We show that this differential is primarily due to decreases in both the association rate of IL-1β to IL-1RI (i.e., less favorable steering) and the association rate of IL-1RAcP to the cytokine/receptor complex. In contrast, gevokizumab has much less effect on the dissociation rates of these interactions. The Fab fragment of gevokizumab affects IL-1β association with sIL-1RI to a degree comparable to that of the intact IgG2, suggesting that the on-rate effects are not due to changes in the rotation correlation rate resulting from a mass differential that would impact diffusion and molecular rotation in solution. In contrast, we also show that gevokizumab has much less of an effect on the binding of IL-1β to the soluble form of the decoy receptor sIL-1RII, with a less than 2-fold difference in association rate and no measurable difference in dissociation rate. The finding that gevokizumab does not appreciably impact sIL-1RII binding kinetics is important, since the soluble form of this receptor serves as a natural circulating inhibitor of IL-1β in the blood. Furthermore, the membrane-associated IL-1RII (IL-1 decoy RII), found predominantly on lymphoid and myeloid cells, including monocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, and B cells, acts as a negative attenuator of IL-1 signaling, and is thought to mediate clearance of IL-1β from systemic circulation (Mantovani et al., 2001; Bourke et al., 2003).

To further understand the mechanistic basis of gevokizumab’s kinetic modulation of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI at the molecular level, it is instructive to consider both the differences and similarities of IL-1β binding to sIL-1RI and sIL-1RII. Both receptors consist of three immunoglobulin-like domains (D1, D2, and D3) (Fig. 8A) which wrap around IL-1β by contacting two discrete regions on this cytokine, designated as site A and site B (Evans et al., 1995; Dinarello, 1996). Binding site A makes contacts with domains 1 and 2 on both receptors, primarily through Van der Waals contacts and hydrogen bonds with receptor main-chain atoms rather than side chains. In contrast, site B makes contact only with domain 3 of both receptors, and is believed to be more dependent on the complementary hydrophilic/hydrophobic profiles of IL-1β and the receptors. Both sites on IL-1β also form extensive salt bridges and hydrogen bonds with the receptors (Vigers et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2010). The receptor binding sites on IL-1β for the two receptors overlap partially, but not completely, as shown by extensive mutagenesis studies and X-ray crystal structures (Grutter et al., 1994; Vigers et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2010).

Although the architecture of the two IL-1β–soluble receptor complexes is very similar, the proportion of binding energy contributed by each of the two sites may differ. Inspection of the crystal structures of the two soluble receptors reveals that the charge distribution is markedly different in the region of domain 3 contacting the IL-1β site (Fig. 8B). Site B on IL-1β is highly charged, with multiple basic residues. This charged area is immediately adjacent to the region in contact with Fab1 in the Fab1·IL-1β complex. (Fig. 8B, left panel). The presence of multiple oppositely charged acidic regions on domain 3 of sIL-1RI (Fig. 8B, middle panel) may play a role in the very rapid association rate of IL-1β through electrostatic steering. The long-range electrostatic attraction of acid and base pairs can lead to remarkably rapid binding formation and high binding probability (Valtiner et al., 2012). In contrast, there are fewer acidic residues in this region of sIL-1RII domain 3, which may explain the slower association rate kinetics of IL-1β·sIL-1RII (Fig. 8B, right panel).

Binding of Fab1 to IL-1β, expected to be similar to that of gevokizumab, confirms that the binding epitope is adjacent to (and slightly overlapping) the highly charged, interacting region included in site B on IL-1β (Blech et al., 2013). Binding of gevokizumab to this highly charged region on IL-1β that interacts with a complementary area on IL-1RI may reduce the rapid association rate by interfering with long-range electrostatic steering. Analysis of the X-ray crystal structure of the IL-1β·sIL-1RI complex suggests that residue Lys94 of IL-1β interacts with Glu252 of sIL-1RI (Wang et al., 2010), whereas both NMR and X-ray crystal structure of IL-1β·Fab1 suggest that this same residue (Lys94 of IL-1β) interacts with residues Asp56, Glu57, and Ser58 of the antibody heavy chain (Blech et al., 2013) (Fig. 8C). Moreover, NMR data suggest that Lys94 of IL-1β is perturbed by Fab1 binding (Blech et al., 2013), which may be significant because this residue is believed to interact with Ile250, Glu252, and Glu259 of sIL-1RI (Wang et al., 2010). This is in contrast to the case with the IL-1β bound to sIL-1RII, as analysis of the crystal structure of the IL-1β·sIL-1RII·sIL-1RAcP ternary complex does not suggest interactions between Lys94 and domain 3 of IL-1RII (Wang et al., 2010). This is consistent with the lack of significant impact of gevokizumab on IL-1β binding to IL-1RII (Fig. 8D).

Although Blech et al. (2013) found that superposition of the IL-1β·Fab1 binary complex with the IL-1RII decoy receptor complex suggests a small steric overlap between Fab1 and the D3 domain of IL-1RII, it is likely that this region does not contribute significantly to the binding of IL-1β to this receptor, and that flexibility of the receptor may allow movement of this domain away from the residues in the interface of the ligand/antibody. In addition to the potential effects on the charge interactions between IL-1β and its receptors, the structural analysis suggests binding of Fab1 to IL-1β induces a minor conformation change in the β4–β5 loop region on IL-1β (site B) that is involved in binding to domain 3 of the receptor, and thus may result in the reduction of IL-1β binding affinity for both IL-1RI and IL-1RAcP (Blech et al., 2013).

There is increasing recognition that many receptor-ligand systems are composed of multiple ligands and receptors, generating complex and context-dependent cellular effects. The ability to use allosteric antibodies therapeutically as “rheostats” rather than “switches” introduces an additional level of subtlety in therapeutic antibody design for regulating the activity of disease-relevant targets. This subtlety is especially important for systems with critical functions, such as IL-1β and its receptors, which play an essential role in the innate immune response. Re-establishment of homeostatic balance may not require dramatic changes such as complete neutralization, but rather it is possible that attenuation of IL-1β activity will provide an advantageous therapeutic approach over complete blockade of the pathway. The data presented in this paper demonstrate that gevokizumab reduces IL-1β activity in a context-dependent manner that allows its regulation by endogenous processes, including clearance by receptor-mediated mechanisms.

Although gevokizumab can be described as a negative allosteric modulator which can be studied using the classic allosteric ternary complex model, it differs from the more commonly studied types of negative allosteric modulators in that it binds to the ligand, and not the receptor, and thus the allosteric and orthosteric sites are on different molecules. Therefore, we propose a new term for this type of modulator, allosteric ligand–modifying antibody, to distinguish it from the classic negative allosteric modulators, in which case both the orthosteric and allosteric sites are found on the receptor.

On the basis of its high potency, novel mechanism of action, long half-life, and high affinity, gevokizumab represents an alternative strategy for the treatment of a number of metabolic, autoimmune, and systemic inflammatory diseases in which the role of IL-1β is central to pathogenesis. Establishment of the therapeutic benefits of gevokizumab’s novel mechanism of action for treatment of IL-1β–mediated diseases is under further investigation in animal models and clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark White, Toshi Takeuchi, Diane Wilcock, Dan Bedinger, David Bohmann, Dan Cafaro, Padma Bezwada, Joel Freeberg, Arnie Horwitz, Susan Kramer, Nikki Hull-Campbell, Niels Jansen, Isabelle Boterman, Marie-Dominique Servais, Christine Miro-Moulet, and Arthur Christpoulous for critical reviews of the manuscript and insightful comments. Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the UCSF Chimera package (Pettersen et al., 2004). Chimera is developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, and is funded by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources [Grant 2P41RR001081] and National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant 9P41GM103311].

Abbreviations

- Ab5

antibody 5

- Fab

antibody binding fragment

- IL-1

interleukin-1

- IL-1Ra

IL-1 receptor antagonist

- IL-1RI

interleukin-1 receptor type I

- IL-1RII

interleukin-1 receptor type II

- IL-1RAcP

interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- sIL-1RI

soluble interleukin-1 receptor type I

- sIL-1RII

soluble interleukin-1 receptor type II

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Issafras, Corbin.

Conducted experiments: Issafras.

Performed data analysis: Issafras, Corbin, Roell.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Issafras, Corbin, Roell, Goldfine.

Footnotes

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Abdiche YN, Lindquist KC, Pinkerton A, Pons J, Rajpal A. (2011) Expanding the ProteOn XPR36 biosensor into a 36-ligand array expedites protein interaction analysis. Anal Biochem 411:139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend WP, Malyak M, Guthridge CJ, Gabay C. (1998) Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: role in biology. Annu Rev Immunol 16:27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunlakshana O, Schild HO. (1959) Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br Pharmacol Chemother 14:48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar V, Yin J, Mirza AM, Phan D, Vanegas S, Issafras H, Michelson K, Hunter JJ, Kantak SS. (2011) Monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-1 beta reduce biomarkers of atherosclerosis in vitro and inhibit atherosclerotic plaque formation in Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 216:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blech M, Peter D, Fischer P, Bauer MM, Hafner M, Zeeb M, Nar H. (2013) One target-two different binding modes: structural insights into gevokizumab and canakinumab interactions to interleukin-1β. J Mol Biol 425:94–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke E, Cassetti A, Villa A, Fadlon E, Colotta F, Mantovani A. (2003) IL-1 beta scavenging by the type II IL-1 decoy receptor in human neutrophils. J Immunol 170:5999–6005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravman T, Bronner V, Lavie K, Notcovich A, Papalia GA, Myszka DG. (2006) Exploring “one-shot” kinetics and small molecule analysis using the ProteOn XPR36 array biosensor. Anal Biochem 358:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos A, Kenakin T. (2002) G protein-coupled receptor allosterism and complexing. Pharmacol Rev 54:323–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church LD, McDermott MF. (2009) Canakinumab, a fully-human mAb against IL-1beta for the potential treatment of inflammatory disorders. Curr Opin Mol Ther 11:81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB, Proudman S, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, Donohue JP, Burstein D, Sun YN, Banfield C, Vincent MS, Ni L, et al. (2011) A randomized, double-blind study of AMG 108 (a fully human monoclonal antibody to IL-1R1) in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Res Ther 13:R125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D. (2007) Why the Schild method is better than Schild realised. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28:608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. (1994) The interleukin-1 family: 10 years of discovery. FASEB J 8:1314–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. (1996) Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood 87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. (2005) The many worlds of reducing interleukin-1. Arthritis Rheum 52:1960–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. (2011) Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 117:3720–3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RJ, Bray J, Childs JD, Vigers GPA, Brandhuber BJ, Skalicky JJ, Thompson RC, Eisenberg SP. (1995) Mapping receptor binding sites in interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist and IL-1 β by site-directed mutagenesis. Identification of a single site in IL-1ra and two sites in IL-1 β. J Biol Chem 270:11477–11483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks ZL, Forte C, Capuano IV, Zhou H, Vanden Bos T, Carter P. (2004) Identification of potent human anti-IL-1RI antagonist antibodies. Protein Eng Des Sel 17:95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst DE. (2004) Anakinra: review of recombinant human interleukin-I receptor antagonist in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 26:1960–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddum JH. (1957) Theories of drug antagonism. Pharmacol Rev 9:211–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser RW. (1993) Antigen-antibody binding and mass transport by convection and diffusion to a surface: a two-dimensional computer model of binding and dissociation kinetics. Anal Biochem 213:152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory KJ, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. (2007) Allosteric modulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Curr Neuropharmacol 5:157–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grütter MG, van Oostrum J, Priestle JP, Edelmann E, Joss U, Feige U, Vosbeck K, Schmitz A. (1994) A mutational analysis of receptor binding sites of interleukin-1 beta: differences in binding of human interleukin-1 beta muteins to human and mouse receptors. Protein Eng 7:663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gül A, Tugal-Tutkun I, Dinarello CA, Reznikov L, Esen BA, Mirza A, Scannon P, Solinger A. (2012) Interleukin-1β-regulating antibody XOMA 052 (gevokizumab) in the treatment of acute exacerbations of resistant uveitis of Behcet’s disease: an open-label pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis 71:563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, Aganna E, McDermott MF. (2004) Spectrum of clinical features in Muckle-Wells syndrome and response to anakinra. Arthritis Rheum 50:607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin TP. (2009) A pharmacology primer: theory, applications, and methods, Academic Press/Elsevier, Amsterdam, Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Kortt AA, Nice E, Gruen LC. (1999) Analysis of the binding of the Fab fragment of monoclonal antibody NC10 to influenza virus N9 neuraminidase from tern and whale using the BIAcore biosensor: effect of immobilization level and flow rate on kinetic analysis. Anal Biochem 273:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Leslie KS, Hachulla E, Quartier P, Gitton X, Widmer A, Patel N, Hawkins PN, Canakinumab in CAPS Study Group (2009) Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med 360:2416–2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Hart RP, Liu XJ, Clevenger W, Maki RA, De Souza EB. (1996) Cloning and characterization of an alternatively processed human type II interleukin-1 receptor mRNA. J Biol Chem 271:20965–20972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell DJ, Bowyer SL, Solinger AM. (2005) Interleukin-1 blockade by anakinra improves clinical symptoms in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease. Arthritis Rheum 52:1283–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Locati M, Vecchi A, Sozzani S, Allavena P. (2001) Decoy receptors: a strategy to regulate inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Trends Immunol 22:328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott MF. (2009) Rilonacept in the treatment of chronic inflammatory disorders. Drugs Today (Barc) 45:423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahan CJ, Slack JL, Mosley B, Cosman D, Lupton SD, Brunton LL, Grubin CE, Wignall JM, Jenkins NA, Brannan CI, et al. (1991) A novel IL-1 receptor, cloned from B cells by mammalian expression, is expressed in many cell types. EMBO J 10:2821–2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myszka DG, He X, Dembo M, Morton TA, Goldstein B. (1998) Extending the range of rate constants available from BIACORE: interpreting mass transport-influenced binding data. Biophys J 75:583–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owyang AM, Issafras H, Corbin J, Ahluwalia K, Larsen P, Pongo E, Handa M, Horwitz AH, Roell MK, Haak-Frendscho M, et al. (2011) XOMA 052, a potent, high-affinity monoclonal antibody for the treatment of IL-1β-mediated diseases. MAbs 3:49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual V, Allantaz F, Arce E, Punaro M, Banchereau J. (2005) Role of interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the pathogenesis of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and clinical response to IL-1 blockade. J Exp Med 201:1479–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. (2004) UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roell MK, Issafras H, Bauer RJ, Michelson KS, Mendoza N, Vanegas SI, Gross LM, Larsen PD, Bedinger DH, Bohmann DJ, et al. (2010) Kinetic approach to pathway attenuation using XOMA 052, a regulatory therapeutic antibody that modulates interleukin-1beta activity. J Biol Chem 285:20607–20614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A, van der Meer JW. (2007) Pathogenesis of familial periodic fever syndromes or hereditary autoinflammatory syndromes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292:R86–R98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, Hanna R, Della Friend, Moore H, Chen H, Farese AM, MacVittie TJ, Virca GD, Sims JE. (2003) The soluble form of IL-1 receptor accessory protein enhances the ability of soluble type II IL-1 receptor to inhibit IL-1 action. Immunity 18:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons JA, Young PR, Duff GW. (1995) Soluble type II interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor binds and blocks processing of IL-1 beta precursor and loses affinity for IL-1 receptor antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:1714–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtiner M, Donaldson SH, Jr, Gebbie MA, Israelachvili JN. (2012) Hydrophobic forces, electrostatic steering, and acid-base bridging between atomically smooth self-assembled monolayers and end-functionalized PEGolated lipid bilayers. J Am Chem Soc 134:1746–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigers GP, Anderson LJ, Caffes P, Brandhuber BJ. (1997) Crystal structure of the type-I interleukin-1 receptor complexed with interleukin-1beta. Nature 386:190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Zhang S, Li L, Liu X, Mei K, Wang X. (2010) Structural insights into the assembly and activation of IL-1β with its receptors. Nat Immunol 11:905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Wasiliew P, Kracht M. (2010) Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Sci Signal 3:cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman J, Gill SJ. (1990) Binding and Linkage: Functional Chemistry of Biological Macromolecules, University Science Books, Mill Valley, CA. [Google Scholar]