Frequent and Relevant Everywhere

No matter which country in the World is evaluated, the prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) is very high. In fact, this is the most frequent cause of gastroenterological consultation. Nevertheless, many patients suffering from FGID never ask for medical assistance, so what physicians see is probably only the tip of the iceberg.

FGID have a significant impact on patients' everyday activities and quality of life, inducing emotional distress because of their chronic symptoms. Moreover, disorders such as functional dyspepsia (FD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) result in heavy economic burdens through direct medical expenses and loss of productivity.

Like other diseases that disturb life's activities, IBS is accompanied by a sphere of biopsychosocial implications. The WHO introduced the concepts of disability, impairment, and handicap to accurately define the impact of diseases on quality of life so that the different designed scales reflect all aspects of life restrictions caused by diseases. Impairment is defined as the signs and symptoms that are a direct consequence of the disease [1]. Disability is the boundary or the loss of ability to perform activities that would be considered normal for a human being (limitations of daily activities caused by a disease). Handicap represents the effects of disease in terms of avoiding patients' development in a social structure (social and environmental limitations because of disease). The impact of FD and IBS include every aspect of life (sleep, sexual activity, diet, work, etc.), and therefore there is a significant disability, impairment, and handicap.

A Simple but Thoughtful Diagnosis

The diagnosis of FGID is, and will be, the result of the evolution of the pathophysiological knowledge. At the moment, there is no biological marker for most of these disorders and diagnosis is mainly based on symptoms. Clinical criteria for FGID diagnosis have been recently reviewed, resulting in the so-called Rome IV criteria [2]. Fulfilling the criteria is mandatory to establish the diagnosis of FD or IBS, but it is also crucial to exclude (in a cost-effective way) any organic disease that might explain the symptoms. The depth of this evaluation will mainly depend on clinical suspicion, evolution time, presence/absence of alarm symptoms, and patient's age.

FD is characterized by one or more of the following symptoms: postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning that are unexplained after a routine clinical evaluation [3]. The broad term FD comprises patients from three diagnostic categories: (1) postprandial distress syndrome, which is characterized by meal-induced dyspeptic symptoms; (2) epigastric pain syndrome, which refers to epigastric pain or epigastric burning that does not occur exclusively postprandially, can occur during fasting, and can even be improved by meal ingestion; and (3) overlapping postprandial distress syndrome and epigastric pain syndrome, which is characterized by meal-induced dyspeptic symptoms and epigastric pain or burning.

Large-scale studies reported a 10–30% prevalence of FD worldwide [4]. The reported prevalence of dyspepsia varies considerably in different populations, due to different interpretations and expressions of symptoms, diagnostic criteria adopted, environmental factors, and local prevalence of organic diseases, such as peptic ulcer and gastric cancer.

IBS is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain associated with defecation or a change in bowel habits. Disordered bowel habits are typically present (i.e., constipation, diarrhea, or a mix of constipation and diarrhea), as are symptoms of abdominal bloating/distention [5]. For both, IBS and FD, symptom onset should occur at least 6 months before diagnosis and symptoms should be present during the last 3 months.

The worldwide prevalence of IBS is 11.2% based on a meta-analysis of 80 studies involving more than 250,000 subjects [6].

Complex Pathophysiology

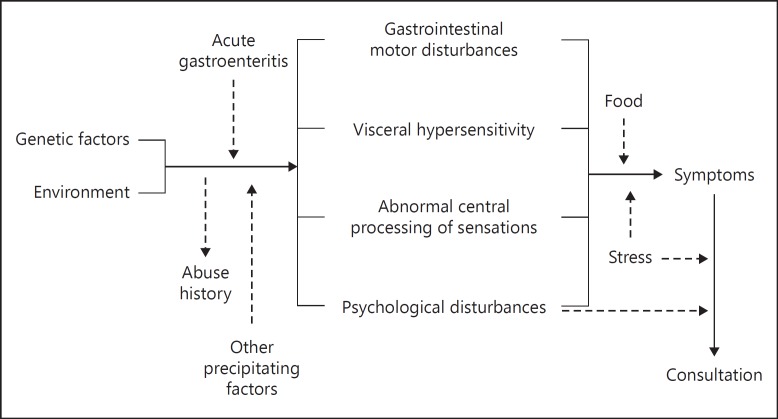

As with any other problem in life, diseases, sometimes (not very frequently) have a single cause, but others - in most of the cases - are multifactorial. For example, anatomical lesions are easy to understand and treatment is obvious: to repair (surgically) the damaged organ. FGID pathophysiology is extremely complex, with digestive, neural, and microbiota interplays. Several mechanisms are involved including intestinal dysmotility, increased visceral sensitivity, disturbed intestinal reflexes (intrinsic and extrinsic), psychological disorders, and dysbiosis (Fig. 1). The predominance and combination of these mechanisms are most probably responsible for the different manifestations of FD and IBS. Therefore, Rome IV defines FGID as disorders of the gut-brain interaction, being symptoms related to any combination of the following: motility disturbance, visceral hypersensitivity, altered mucosal and immune function, altered gut microbiota, and altered central nervous system (CNS) processing [2].

Fig. 1.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders pathophysiology is extremely complex, with digestive, neural, and microbiota interplays.

This multifactorial origin of symptoms can only be (partially) explained under the biopsychosocial model: early in life, genetics, sociocultural influences, and environmental factors may affect one's psychosocial development in terms of personality traits, susceptibility to life stresses, psychological state, and cognitive and coping skills; these factors also influence the susceptibility to gut dysfunction (abnormal motility or sensitivity, altered mucosal immune dysfunction or inflammation), and the microbial environment, as well as the effect of food and nutritional substances; furthermore, these brain-gut variables reciprocally influence the CNS expression [2, 7, 8].

Monotarget versus Multitarget Treatments

The close relationship between the CNS and the enteric nervous system (the so-called brain-gut axis), or even more, the bidirectional correlation among the CNS, the enteric nervous system, and the microbiota (the brain-gut-microbiota axis), is the basis of most of the actual research on FD and IBS, not only concerning pathophysiology but also treatment. Whether therapy has to be aimed at the gut, the neural pathways controlling bowel motility and perception, or the processing mechanisms of symptoms and disease behavior, is still unclear. It is conceivable that in the near future better understanding of IBS pathophysiology will help us to tailor treatment for different FGID patients. At the moment, subclassification of the diverse patterns of symptomatology allows adjustment of new treatments for FGID according to the clinical symptom predominance for each patient only. The knowledge of motor and sensory responses to different stimuli in IBS patients, and the pathways to the CNS is an important source of information for the development of new molecules.

However, it is not likely that one single treatment will help every patient with FD or IBS, and many of them will need a more complex approach with a multidisciplinary therapy (diet, psychotherapy, medications). On the contrary, medications with just a single mechanism of action will help only a subset of patients (suffering this specific pathophysiological abnormality). Prokinetics, antispasmodics, antinociceptives, selective antibiotics, and probiotics, among others, are used in patients with FGID, each being effective is some cases. Nevertheless, very frequently, they have to be used in combination to get a more pronounced and general effect.

Herbal Medications

Herbal drugs have a long history of use in the treatment of functional disorders. Their mechanisms of action are not completely understood, but it has been known for centuries that they contain, for example, essential oils, which are known for their spasmolytic, carminative, and local anesthetic actions. However, in the past, little attention has been paid to the evaluation of herbal remedies in the therapy of patients with FGID [9]. The herbal medicinal product STW 5 (Iberogast, Steigerwald, Darmstadt, Germany) is a fixed combination of nine different herbal extracts, each contained in a very low concentration compared with dosages used in single drug treatment. Its clinical efficacy for both FD and IBS has been demonstrated in well-designed double blind, placebo-controlled, trials [10, 11].

The extracts exert different proven pharmacological effects on different regions of the gastrointestinal tract and thus address the whole symptom complex of FD and IBS [12].

In vitro studies of gastric motility have shown that ethanol-free lyophilisates of STW 5 exert pleiotropic effects on the muscles of different gastric regions [13]. Remarkably, individual components produce differential effects on the myogenic action of the proximal and distal stomach, that is, calcium-mediated actions of the constituents can be converse between the fundic and the antral regions. FD has been shown to be associated with an impairment of gastric accommodation in the fundus region accompanied by antral hypomotility. Consequently, STW 5 seems to improve gastric dysmotility by the relaxation of the proximal stomach and an enhancement of antral motility [13]. Data in healthy volunteers confirmed that this herbal preparation increased the proximal gastric volume, a surrogate marker for gastric accommodation and elevated antral pressure at the same time [14].

An additional effect of STW 5 may result from a modulation of visceral nociception, resulting from the antinociceptive effect of STW 5 to both mechanical and chemical stimuli [15]. Moreover, therapeutic benefits might be related to its anti-inflammatory properties, as shown in animals using TNBS and DDS induced colitis models [16, 17].

The tolerability of STW 5 was favorable, both in clinical studies and in post-marketing use [18]. Various studies evaluated the tolerability profile of STW 5: the incidence of adverse drug reactions was 0.04%. The worldwide spontaneous reporting system confirmed this profile. STW 5 has a favorable tolerability which is relevant for long-term treatment.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980. International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1262–1279. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, Malagelada JR, Suzuki H, Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380–1392. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2661–2666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1393–1407. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712–721.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossman DA. Presidential address: gastrointestinal illness and biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258–267. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson Coon J, Ernst E. Systematic review: herbal medicinal products for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1689–1699. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melzer J, Rösch W, Reichling J, Brignoli R, Saller R. Meta-analysis: phytotherapy of functional dyspepsia with the herbal drug preparation STW 5 (Iberogast) Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1279–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madisch A, Holtmann G, Plein K, Hotz J. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with herbal preparations: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Aziz H, Kelber O, Lorkowski G, Storr M. Evaluating the multitarget effects of combinations through multistep clustering of pharmacological data: the example of the commercial preparation Iberogast. Planta Med. 2017;83:1130–1140. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-116852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schemann M, Michel K, Zeller F, Hohenester B, Rühl A. Region-specific effects of STW 5 (Iberogast) and its components in gastric fundus, corpus and antrum. Phytomedicine. 2006;13((suppl 5)):90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilichiewicz AN, Horowitz M, Russo A, Maddox AF, Jones KL, Schemann M, Holtmann G, Feinle-Bisset C. Effects of Iberogast on proximal gastric volume, antropyloroduodenal motility and gastric emptying in healthy men. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1276–1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller SF, Klement S. A combination of valerian and lemon balm is effective in the treatment of restlessness and dyssomnia in children. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael S, Kelber O, Hauschildt S, Spanel-Borowski K, Nieber K. Inhibition of inflammation-induced alterations in rat small intestine by the herbal preparations STW 5 and STW 6. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadie W, Abdel-Aziz H, Zaki HF, Kelber O, Weiser D, Khayyal MT. STW 5 is effective in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in rats. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1445–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1473-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottillinger B, Storr M, Malfertheiner P, et al. STW 5 (Iberogast®) - a safe and effective standard in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2013;163:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s10354-012-0169-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]