Abstract

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) is widely used as a molecular tool to assess protein expression and localization. In C. elegans, the signal from weakly expressed GFP fusion proteins is masked by autofluorescence emitted from the intestinal lysosome-related gut granules. For instance, the GFP fluorescence from SKN-1 transcription factor fused to GFP is barely visible with common GFP (FITC) filter setups. Furthermore, this intestinal autofluorescence increases upon heat stress, oxidative stress (sodium azide), and during aging, thereby masking GFP expression even from proximal tissues. Here, we describe a triple band GFP filter setup that separates the GFP signal from autofluorescence, displaying GFP in green and autofluorescence in yellow. In addition, yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) remains distinguishable from both the yellowish autofluorescence and GFP with this triple band filter setup. Although some GFP intensity might be lost with the triple band GFP filter setup, the advantage is that no modification of currently used transgenic GFP lines is needed and these GFP filters are easy to install. Hence, by using this triple band GFP filter setup, the investigators can easily distinguish autofluorescence from GFP and YFP in their favorite transgenic C. elegans lines.

Keywords: Microscopy, Filter set, Fluorescent protein, GFP, YFP, Autofluorescence, Gut granules, Lysosome-related organelles, Age-pigments, Lipofuscin, Aging, Transcription factor, SKN-1, HSF-1, C. elegans

Background

Major sources of autofluorescence include intracellular lysosome-derived granules, mitochondria (i.e., autofluorescent molecules such as NAD(P)H and flavins), or extracellular collagen (Hermann et al., 2005; Monici, 2005). During aging, autofluorescent materials such as lipofuscin and advanced glycation end-products (AGE) accumulate. In the nematode C. elegans, the autofluorescence of gut granules starts already during embryogenesis, reflecting the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles (Hermann et al., 2005). This prominent autofluorescence of these lysosome-related gut granules in the intestine continues throughout development and adulthood. The source of the autofluorescence, whether it is lipofuscin, AGE, tryptophan metabolites, or something else, is still unclear. However, this autofluorescence increases during aging and the two main tissues that show the highest autofluorescence are the intestine and the uterus in C. elegans (Pincus et al., 2016). With current fluorescent filter sets (TRITC, DAPI, FITC), three different autofluorescent wavelengths have been characterized in C. elegans. The red autofluorescence (visualized by TRITC) progressively increases with age, the blue autofluorescence (visualized by DAPI) peaks right before death, and the green autofluorescence (visualized by FITC) is a mixture from the red and blue autofluorescence (Pincus et al., 2016).

The multicellular model organism C. elegans is transparent, allowing GFP fluorescence to be assessed in vivo non-invasively (Chalfie et al., 1994). With commonly used GFP filter sets, for instance, FITC with an excitation center wavelength of 470 nm and a full bandwidth of 40 nm (470/40 nm), and emission range of 525/50 nm, the intestinal autofluorescence overlaps with the GFP signal. Previously, knockdowns by RNA interference (RNAi; e.g., tdo-2 RNAi) or gut granule-loss (glo) mutations (Hermann et al., 2005; Coburn et al., 2013), which either diminish or eliminate the intestinal autofluorescence, have been applied to the desired GFP transgenic C. elegans lines to overcome this problem. However, RNAi knockdowns or mutations that help to diminish autofluorescence alter gene function and might cause artifacts. In addition, there are transgenic GFP fusions of several stress response-regulating transcription factors (DAF-16::GFP, HSF-1::GFP, HLH-30::GFP, SKN-1::GFP) that are routinely used to assess cytoplasmic to nuclear translocation in intestinal cells as a proxy for their activation (Henderson and Johnson, 2001; Libina et al., 2003; Kwon et al., 2010; Lapierre et al., 2013; Morton and Lamitina, 2013; Ewald et al., 2015 and 2017b). Particularly, the transgenic SKN-1::GFP fusion is barely visible and is masked by intestinal autofluorescence even in larval C. elegans (Havermann et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2017).

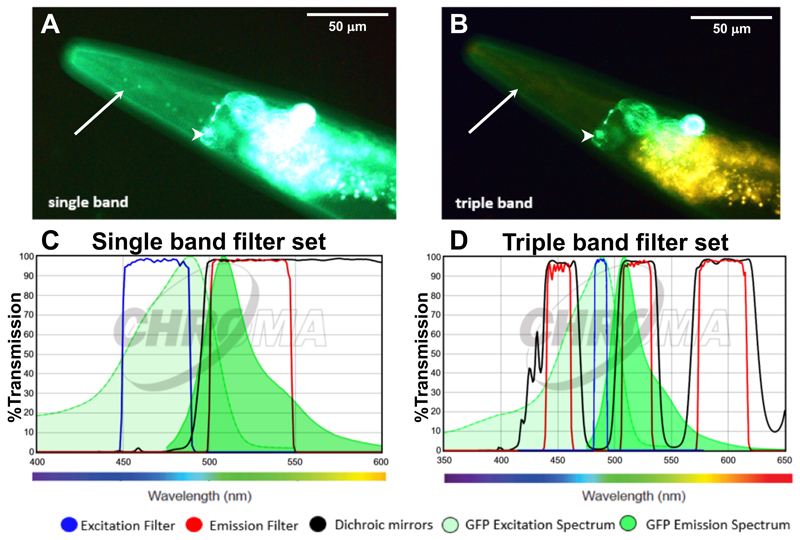

To overcome the problem of autofluorescence masking intestinal GFP, Oliver Hobert (http://www.bio.net/mm/celegans/1998-November/001769.html) and several other investigators in the C. elegans community had proposed the principle of this combination of GFP filter sets. Optimization of these GFP filter sets by the Blackwell lab made it possible to assess the subcellular localization of SKN-1 and other proteins that were difficult to visualize (An and Blackwell, 2003). Unfortunately, these previous filter sets are not on sale anymore. Here, we describe the currently and commercially available filters that can be used to rebuild these GFP-filter settings. In contrast to the single band FITC GFP filter set, the proposed triple band GFP filter set has a very narrow excitation bandwidth of 10 nm, which is right by the maximum peak for the S65C mutant GFP excitation (488 nm) that is commonly used in C. elegans (Boulin et al., 2006; Heppert et al., 2016). More importantly, the emission filter used here has a first pass-through (520/20 nm) for the light emitted close to the GFP emission peak (509 nm) and a second pass-through (595/40 nm) from the light around the autofluorescence emission, allowing the separation of GFP (visible in green) and autofluorescence (visible in yellow).

Materials and Reagents

250 ml glass Erlenmeyer flask

1.5 ml centrifuge tubes

Microscope slides (size: 76 mm x 26 mm, 1 mm thick; VWR, Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog number: 631-1303)

Cover slip (size: 18 mm x 18 mm; VWR, catalog number: 631-1567)

Tape (MILIAN, catalog numbers: 140255B, BA-5419-07)

-

C. elegans strains (available at Caenorhabditis Genetics Center [CGC] https://cbs.umn.edu/cgc/home) or if not available at CGC, can be requested directly from the research labs that generated them: N2 C. elegans wild-type Bristol, LD1 Is007 [Pskn-1::skn-1b/c::gfp; pRF4 rol-6 (su1006)], LSD2022 spe-9(hc88); jgIs5 [Prol-6::rol-6::gfp, Pttx-3::gfp], EQ87 iqIs28 [pAH71 Phsf-1::hsf-1::gfp; pRF4 rol-6 (su1006)], BT24 rhIs23 [gfp::him-4] III, NL5901 pkIs2386 [Punc-54::alpha-synuclein::YFP + unc-119(+)])

Note: For culturing and handling C. elegans, please see Stiernagle (2006).

Agarose (Conda, catalog number: 8010)

KH2PO4 (Merck, catalog number: 1048731000)

Na2HPO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: S5136)

NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: S3014)

MgSO4 (Fisher Scientific, catalog number: 10316240)

-

Levamisole hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: L0380000) (2 mM) solved in M9 buffer

Note: Used here to paralyze worms; it is not recommended to use sodium azide (NaN3) (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: S2002-100G) (20 mM, solved in M9 buffer).

Agarose pads (see Recipes)

M9 buffer (see Recipes) (Stiernagle, 2006; He, 2011)

Equipment

-

1

Autoclave

-

2

Microwave to heat up agarose

-

3

Heated water bath or heat block to keep agarose molten

-

4

For loading C. elegans onto agarose pads:

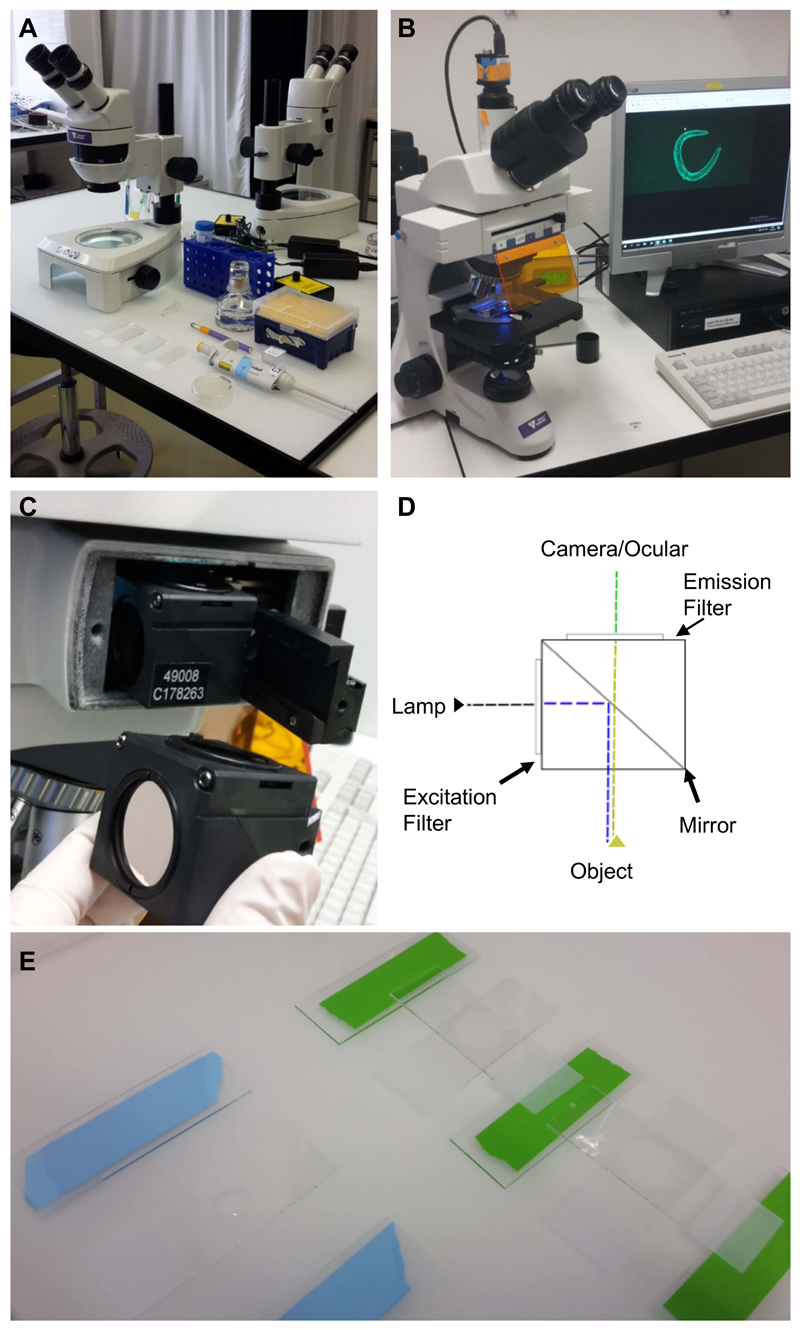

Stereomicroscope, worm pick, pipettes (Figure 1A) (Ewald et al., 2017a)

Figure 1. Equipment and experimental setup.

A. Equipment and utilities for mounting C. elegans on microscope slides. Shown from the top left: a stereoscope, M9 buffer in a falcon tube, levamisole in a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube, a pipette with tips, a worm-pick to mount C. elegans in the liquid droplet, microscope slides with 2% agarose pad, and C. elegans on culturing plate. B. Upright bright field fluorescence microscope setup; C. The filter cube and its position in the microscope; D. A schematic representation of the filter cube. The dashed lines indicate the pathway of the light through the filter cube, while the arrows indicate the filters and the mirror. E. Preparation of the 2% agarose pad slides for microscopy. On the left side is a slide with a drop of 2% agarose dropped between two blue taped slides, while on the right side the agarose drop was already covered by another slide perpendicular to the green taped slides.

-

5.

Upright bright field fluorescence microscope (Tritech Research, model: BX-51-F, Figure 1B)

-

6.

Camera (The Imaging Source, model: DFK 23UX236, with IC Capture 2.4 software)

It is important to use a color camera, since a monochrome camera is unable to distinguish between colors, so the filter set would be ineffective.

-

7.

Triple band filter sets

Note: The triple band filter sets used here are from Chroma Technology Corp., but similar filter sets can be acquired from other manufacturers.

The triple band filter sets consist of the 69000 ET-DAPI/FITC/TRITC (69000x, 69000m, 69000bs, EX/EM 25 mm, ringed, DC 25.5 x 36 x 1 mm) (Chroma Technology, catalog number: 69000). However, the excitation filter 69000x is exchanged with an ET485/10x narrow band excitation filter (25 mm, ringed; Chroma Technology, catalog number: ET485/10x). The interpretation of the filter nomenclature for example for ET485/10x is: “ET” stands for magnetron sputtered exciter, “485” indicates the center wavelength of 485 nm and the “/10” indicates the full bandwidth of 10 nm (i.e., +/- 5 nm from the center), and the “x” stands for excitation. Hence, the triple band filter set consists of the ET485/10x excitation filter, the 69000bs dichroic beam splitter, and the 69000m emission filter. The triple band filters are then assembled in a microscope filter cube. A schematic of this setup is shown in Figures 1C and 1D. A comparison between the filter set properties and the resulting images are shown in Figure 2. In brief, the 69000m emission filter allows light coming through from 520/20 nm (green) and from 595/40 (yellow to orange/red) but blocks the greenish to yellow light (535-572 nm), which is the key feature of the triple band filter set that allows distinguishing GFP from autofluorescence (Figure 2). This is in contrast to a GFP long-pass emission filter (ET500lp, > 500 nm), which allows all the light from green to red to pass through.

Figure 2. Applying the triple band filter set to distinguish between GFP signal and C. elegans autofluorescence.

A-B. The LSD2022 C. elegans strain expresses an integrated collagen::GFP transgene (ROL-6::GFP), which is visible in the cuticle (white arrow). In addition, the strain LSD2022 expresses GFP driven by the ttx-3 promoter in the AIY interneuron pair (white arrowhead) (Kim et al., 2010). A C. elegans worm (LSD2022) imaged with a commonly used single band filter set (A). The same animal imaged with the triple band filter set. Green is GFP and yellow is autofluorescence (B). C. Transmission graph of the single band filter set we used in (A) [49002-ET-EGFP (FITC/Cy2) by Chroma]; D. Transmission graph of the triple band filter setup used for (B). The triple band filter setup consists of a narrow band ET485/10x excitation filter, a 69000bs dichroic mirror filter, and a 69000m emission filter, which allows light coming through from 520/20 nm (green) and from 595/40 (yellow to orange/red). However, the 69000m emission filter blocks the greenish to yellow light (535-572 nm), which is the key feature that helps to distinguish GFP from autofluorescence. (C and D) The graphs are both adapted from www.chroma.com.

Software

IC Capture 2.4 software (https://www.theimagingsource.com/support/downloads-for-windows/end-user-software/iccapture/)

ImageJ (https://imagej.net/Image_Stitching)

Procedure

Prepare 2% agarose pads (adapted from http://www.wormatlas.org/agarpad.htm): Place three microscope slides next to each other. Place a piece of tape on the two outer slides (Figure 1E). To obtain a 2% agarose solution, add 1 g of agarose into 50 ml M9 buffer using a 250 ml glass Erlenmeyer flask.

Heat the solution until it is boiling and mix well to get all agarose into solution. To prevent the solution from solidifying, keep it at 65 °C, for example, in a heated water bath (see Note 1). Pipette a drop of the 2% agarose solution onto the middle of a slide and immediately place another microscope slide in a 90° angle on top of it, so that it is secured by the two stickered slides hovering over the middle one resulting in an even thickness of the solidifying agarose (Figure 1E, see Note 2). Wait for 1 min, then carefully remove the top microscope slide by sliding it off. After around 5 min, the pad is dry enough and can be used for microscopy.

Place a drop (10 μl) of 1 mM levamisole (or tetramisole) dissolved in M9 buffer to paralyze C. elegans on the agarose pad. Add 10-20 C. elegans by picking them into the drop. Carefully cover the agarose pad with a coverslip.

Use a fluorescent microscope to take images of the prepared C. elegans (see Note 3).

Data analysis

1. Scoring nuclear localization of SKN-1 transcription factor

The transcription factor SKN-1 is the orthologue of the mammalian Nrf/CNC proteins (Nrf1, 2, 3) and is essential for oxidative stress response, protein and lipid homeostasis, and aging (Blackwell et al., 2015). Assessing the activation of SKN-1 is important to gain insights into these cellular protective mechanisms. The skn-1 gene encodes four protein isoforms (SKN-1a, b, c, d) (Blackwell et al., 2015). The SKN-1b isoform is predominantly expressed in the ASI pair of sensory neurons and is important for dietary restriction-induced longevity in liquid (Bishop and Guarente, 2007). The SKN-1c isoform is predominantly expressed in the intestine and is important for oxidative stress response and longevity through reduced insulin/IGF-1 (Tullet et al., 2008; Ewald et al., 2015) and TOR signaling (Robida-Stubbs et al., 2012).

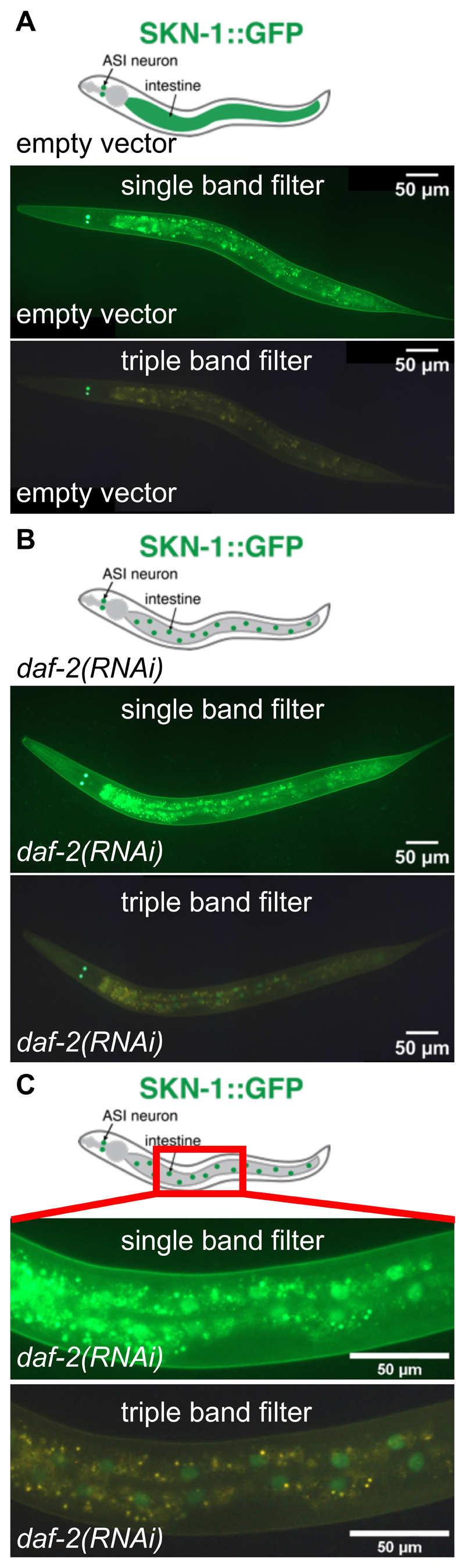

The transgenic C. elegans line LD1 ldIs007 [Pskn-1::skn-1b/c::gfp] (An and Blackwell, 2003) expresses both SKN-1 b and c isoforms. Under unstressed conditions, SKN-1::GFP is visible in ASI neurons, but barely visible in intestinal cells, where it is presumably predominantly localized in the cytoplasm. Under oxidative stress conditions, SKN-1::GFP translocates from the cytoplasm into the nuclei of intestinal cells (An and Blackwell, 2003). A major problem is the scoring of this SKN-1::GFP translocation, since autofluorescence emitted from the intestinal lysosome-related gut granules masks the weakly expressed SKN-1::GFP even during larval stages (Figure 3). The triple band filter sets proposed here allow GFP to appear in green and autofluorescence in yellow (Figures 3B and 3C). This facilitates scoring SKN-1::GFP nuclear localization in the intestinal nuclei.

Figure 3. SKN-1::GFP nuclear localization.

In (A) and (B), the same transgenic LD1 ldIs007 [Pskn-1::skn-1b/c::gfp] C. elegans (anterior to the left, ventral side down) at larval stage 4 (L4) is imaged with the single band filter set (middle panel; 1/30 sec exposure time) or the triple band filter set (bottom panel; 1/30 sec exposure time). Top panel shows schematic representation of SKN-1::GFP depicted in green. A. Transgenic LD1 C. elegans imaged at L4 larval stage fed with control RNAi bacteria carrying an empty vector (L4440), starting from the L1 larval stage. SKN-1::GFP is diffuse and barely visible in the intestine. Note that green signal observed in the intestine here is mainly gut autofluorescence. B. Transgenic LD1 C. elegans imaged at L4 larval stage treated with daf-2 RNAi (which reduces insulin/IGF-1 signaling), starting from the L1 larval stage. SKN-1::GFP is localized in the intestinal nuclei and prominently visible with the triple band filter sets by displaying the GFP in green and the autofluorescence in yellow.

Note: Treatment of daf-2(RNAi) does not increase skn-1 expression levels (Tullet et al., 2008; Ewald et al., 2015). (C) shows a magnified section (1/30 sec exposure time) indicated by the red box in the schematic (top panel). For (A) and (B), images were stitched together using ImageJ (https://imagej.net/Image_Stitching) (Preibisch et al., 2009).

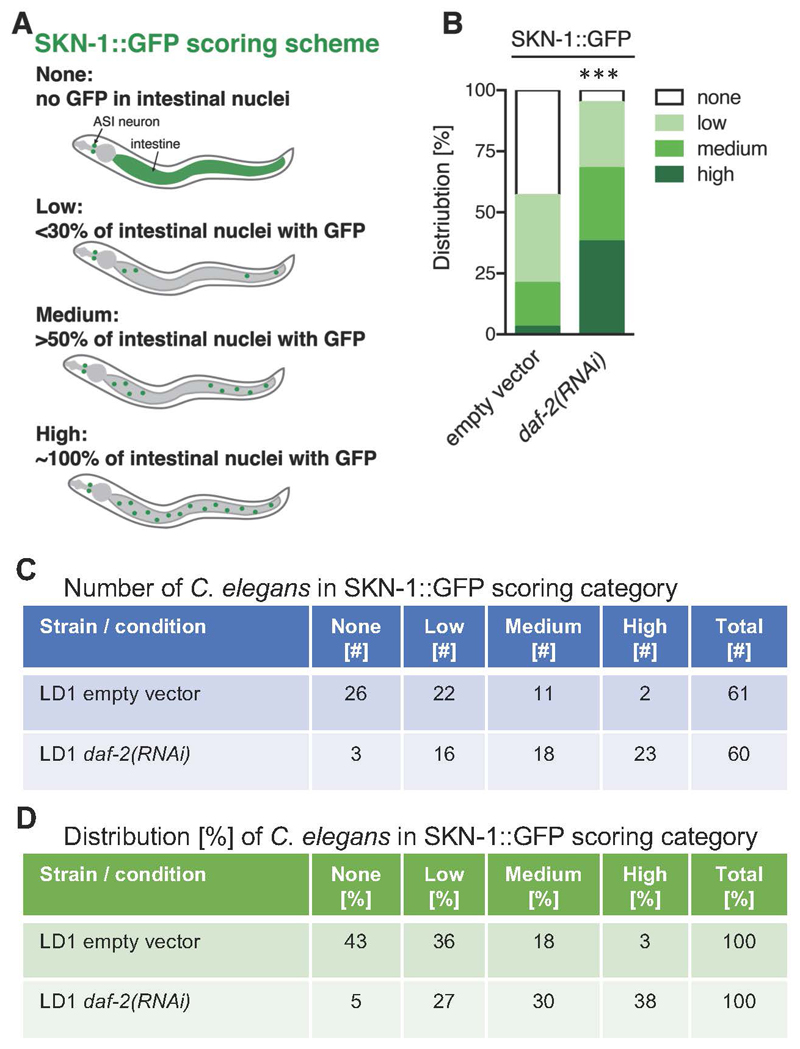

The SKN-1::GFP scoring scheme as described in Robida-Stubbs et al. (2012) and Ewald et al. (2017b) is divided into four categories:

None: no GFP observed in intestinal nuclei;

Low: up to one-third of intestinal nuclei show GFP;

Medium: more than half of the intestinal nuclei show GFP;

High: all intestinal nuclei show GFP (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Quantification of SKN-1::GFP nuclear localization.

A. Schematic representation of SKN-1::GFP (green) scoring categories; B. Graphical representation of distribution of C. elegans found in the individual SKN-1::GFP scoring categories. LD1 transgenic L4 animals expressing a translational fusion of SKN-1 protein tagged with GFP [ldIs007 (Pskn-1::skn-1b/c::gfp)] were scored. C. Table of scoring data of the number of C. elegans in the SKN-1::GFP scoring categories; D. The data from (C) was used to calculate the distribution of the C. elegans found in SKN-1::GFP scoring categories represented in percent, which is also graphical represented in (B). N > 60, one trial. *** < 0.0001 P value was determined by Chi2-test.

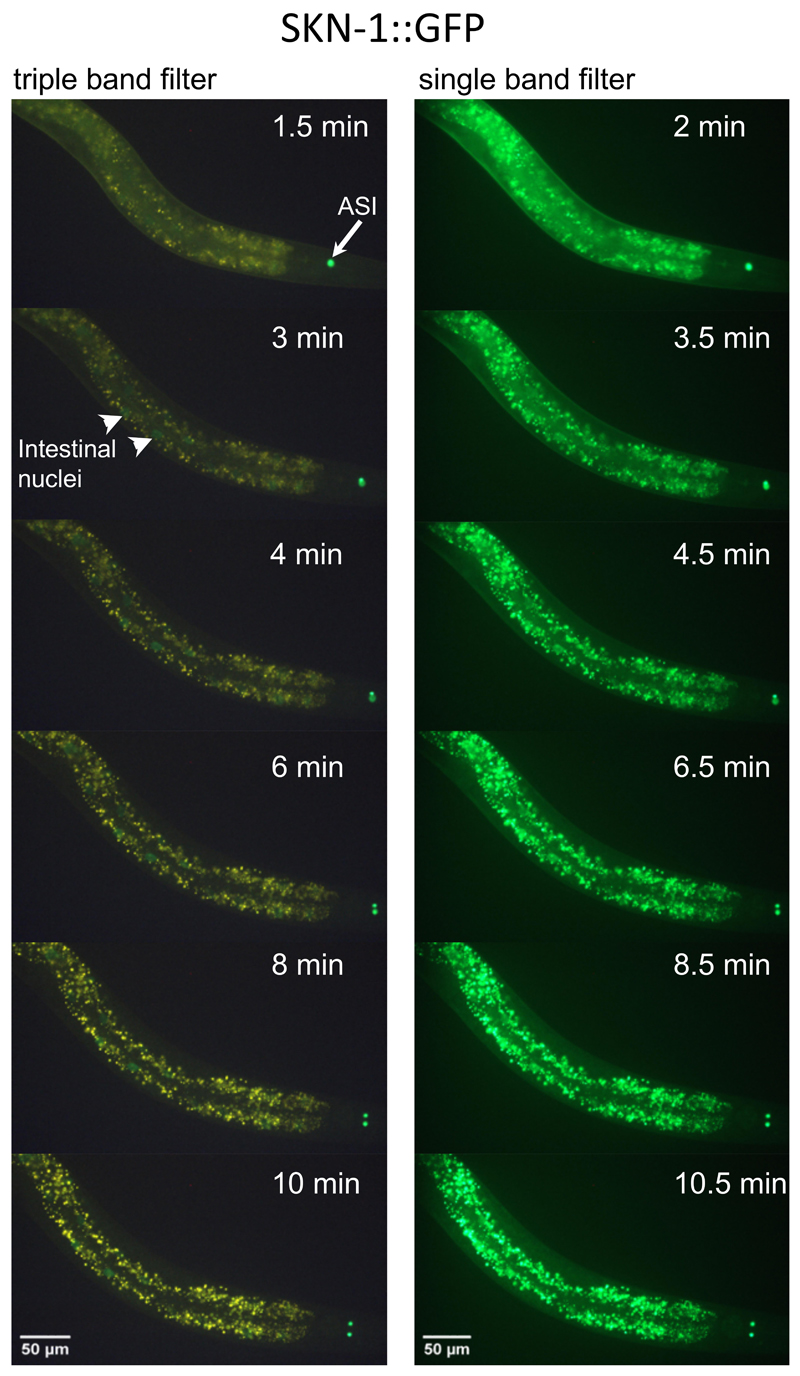

An example result for scoring SKN-1::GFP localization under control (empty vector) and under reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling conditions [daf-2(RNAi)] is shown in Figure 4B, and the corresponding number and percent distribution of C. elegans in each SKN-1::GFP scoring category is shown in Figures 4C and 4D, respectively. C. elegans has about 30-34 intestinal nuclei (McGee et al., 2011) and in Figure 3B SKN-1::GFP is visible in all 34 nuclei when treated with daf-2(RNAi). For each condition, it is recommended to score at least 60 C. elegans (see Note 4). For statistical comparison, the Chi-square test can be applied. Importantly, upon oxidative stress, SKN-1::GFP can move into the nucleus within minutes (An and Blackwell, 2003; Kell et al., 2007). For instance, sodium azide (NaN3), an inhibitor of cytochrome oxidase and a compound commonly used to paralyze C. elegans, drives SKN-1::GFP into the nucleus within 3-6 min (Figure 5), depending on the concentration used (5-10 mM) (An and Blackwell, 2003). In addition, the intestinal autofluorescence increases within 10 min exposure to 10 mM sodium azide (Figure 5). Therefore, we recommend using either levamisole or tetramisole (a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist that causes prolonged contraction of nematode muscles) to paralyze these transgenic SKN-1::GFP C. elegans.

Figure 5. Time-course of SKN-1::GFP nuclear localization during oxidative stress.

Shown is the same transgenic LD1 C. elegans (head to the right, ventral side down) at larval stage 4 (L4) imaged with the triple band filter set (left panel; 1/30 sec exposure time) and the single band filter set (right panel; 1/30 sec exposure time) over the time-course of 10.5 min treated with 10 mM sodium azide (NaN3). After 3 min, SKN-1::GFP (white arrowhead) starts to become visible in intestinal nuclei when imaged with the triple band filter set (left panel). The white arrow indicates constitutively expressed SKN-1::GFP in the ASI neuron pair. Note that over time the intestinal autofluorescence also increases.

2. Scoring HSF-1 transcription factor activation

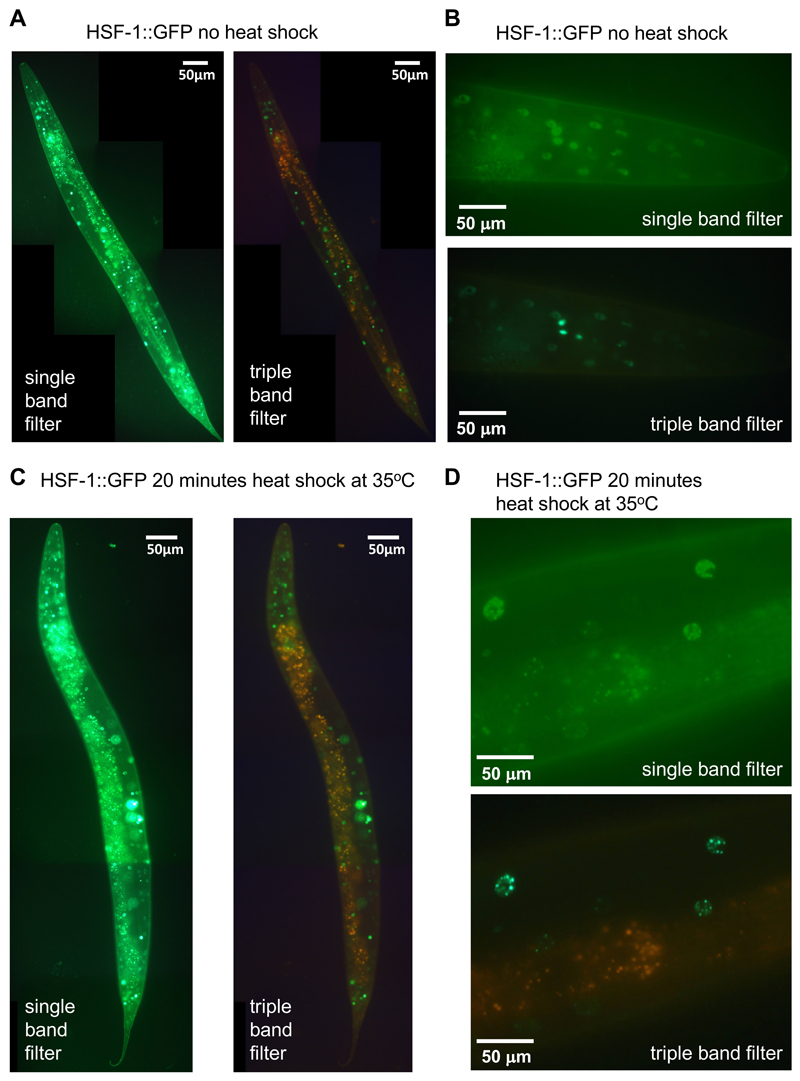

Similarly, this triple band filter set can be used for scoring the activation of other transcription factors, such as HSF-1, DAF-16, HLH-30, and others. For the HSF-1 transcription factor, autofluorescence also plays an interfering role since heat shock increases autofluorescence of intestinal cells (Figure 6). Upon heat shock (1-20 min at 35 °C), HSF-1 tagged GFP (HSF-1::GFP) forms foci in the hypodermal nuclei, but the HSF-1::GFP foci are difficult to score in the intestinal nuclei (Chiang et al., 2012; Morton and Lamitina, 2013). Figure 7 shows that the triple band filter set facilitates scoring of HSF-1::GFP foci in the intestinal nuclei, since autofluorescence appears yellowish. The HSF-1::GFP foci scoring is described elsewhere (Chiang et al., 2012; Morton and Lamitina, 2013).

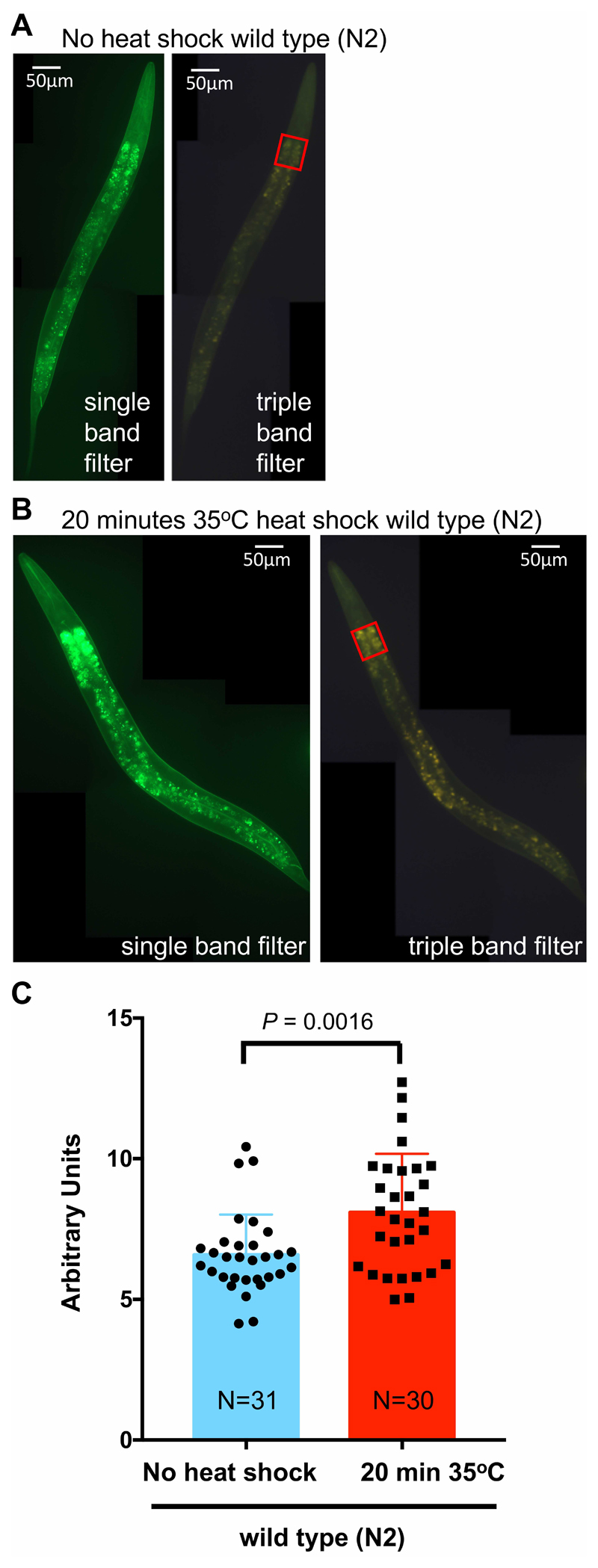

Figure 6. Heat shock increases intestinal autofluorescence.

A. Wild-type (N2) L4 C. elegans without heat shock, imaged with the single band filter set (left panel) and the triple band filter set. Anterior to the top, ventral side to the right. B. Wild-type (N2) L4 C. elegans with a 20 min heat shock at 35 °C, imaged with the single band filter set (left panel) and the triple band filter set. Anterior to the top, ventral side to the right. C. Using the triple band filter set, about 30 wild-type (N2) L4 C. elegans either not subjected to heat shock or treated with a 20 min heat shock at 35 °C were imaged. To quantify the intestinal autofluorescence, the pixel values of the same region of interest at the anterior intestine [red rectangle shown in (A) and (B)] were measured and background was subtracted by placing the same rectangular area next to the C. elegans using ImageJ. The arbitrary unit was derived by first weighting each pixel and then normalizing to the measured area. In ImageJ, each pixel is given a value from 0 to 255 (dark to bright), which was multiplied with the number of pixels measured for a given pixel value. Then the sum of these weighted pixels was divided by the total number of pixels in the measured area. Data is represented as scatter dot plot (individual C. elegans) with the mean shown as a bar with standard deviation. P value was derived from an unpaired two-tailed t-test. For (A) and (B), images were stitched together using ImageJ (https://imagej.net/Image_Stitching) (Preibisch et al., 2009).

Figure 7. HSF-1::GFP nuclear foci formation upon heat shock.

A. Transgenic EQ87 iqIs28 [hsf-1::gfp] L4 C. elegans without heat shock, imaged with the single band filter set (left panel) and the triple band filter set (right panel). Anterior to the top, ventral side left. 1/30 sec exposure time). B. Head region of a transgenic animal without heat shock, imaged at a higher magnification with the single band filter set (left panel) and the triple band filter set (right panel; 1/55 sec exposure time). C. With a 20 min heat shock at 35 °C, imaged with the single band filter set (top panel) and the triple band filter set (bottom panel; 1/30 sec exposure time). D. Head region of a transgenic animal with a 20 min heat shock at 35 °C, imaged at a higher magnification with the single band filter set (left panel) and the triple band filter set (right panel; 1/55 sec exposure time). For (A) and (C), images were stitched together using ImageJ (https://imagej.net/Image_Stitching) (Preibisch et al., 2009).

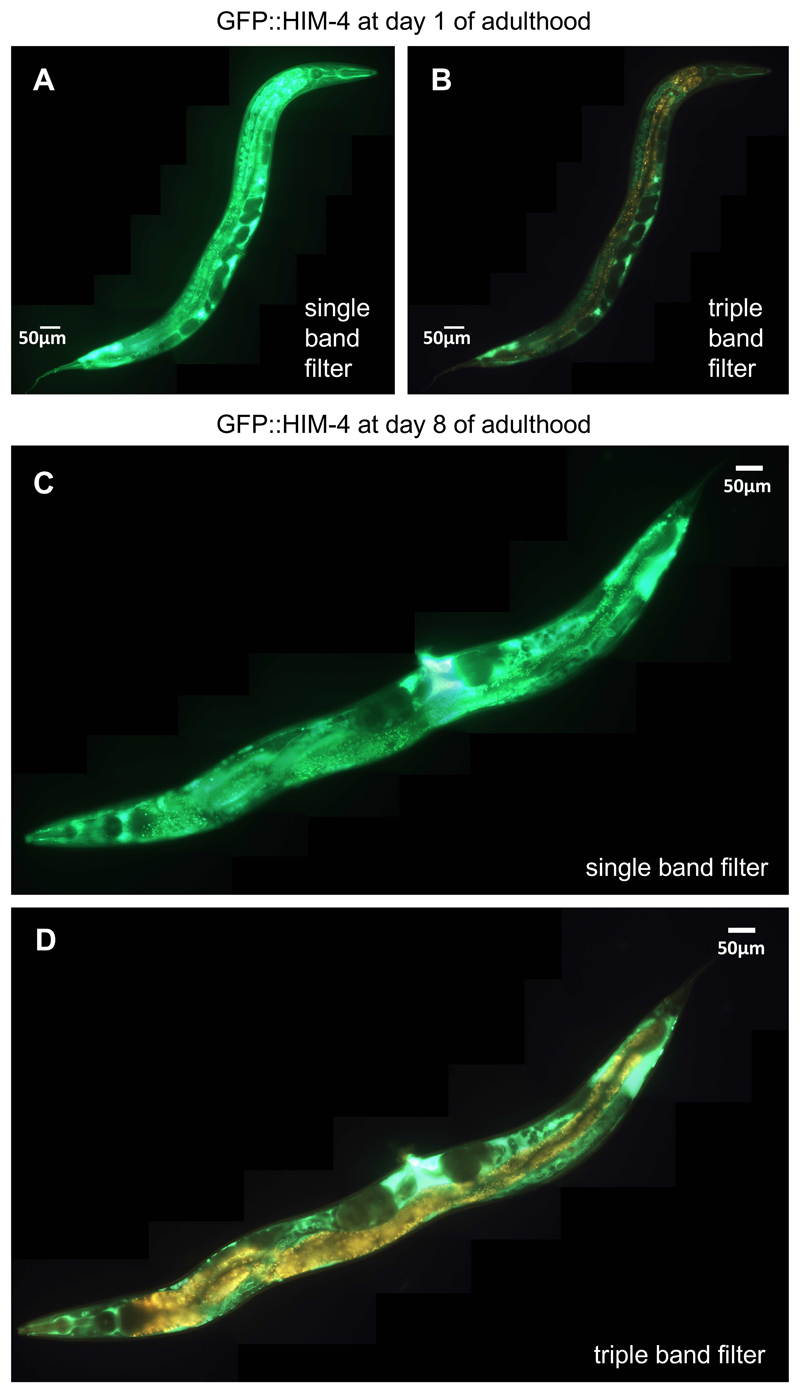

3. Scoring GFP-tagged proteins during old age

During aging, the C. elegans autofluorescence increases (Pincus et al., 2016), making it more difficult to score levels and localization of GFP-fused proteins. Figure 8 shows transgenic animals that express a GFP-tagged HIM-4 fusion, which is localized to the basement membrane, either imaged with standard filter sets or with the triple band filter sets (on day 1 and day 8 of adulthood). Although some of the GFP signal might be lost with the triple band filter set, the GFP signal can be easily distinguished from the age-dependent autofluorescence.

Figure 8. Autofluorescence increases with age masking GFP signal even from proximal tissues.

In (A) and (B), the same transgenic BT24 rhIs23 [gfp::him-4] C. elegans (anterior to the top, ventral side right) at day 1 of adulthood is imaged with the single band filter set (A; 1/30 sec exposure time) or the triple band filter set (B; 1/30 sec exposure time). In (C) and (D), another transgenic animal (anterior to the bottom, ventral side up) at day 8 of adulthood is imaged with the single band filter set (C; 1/30 sec exposure time) or the triple band filter set (D; 1/30 sec exposure time). For (A)-(D), images were stitched together using ImageJ (https://imagej.net/Image_Stitching) (Preibisch et al., 2009).

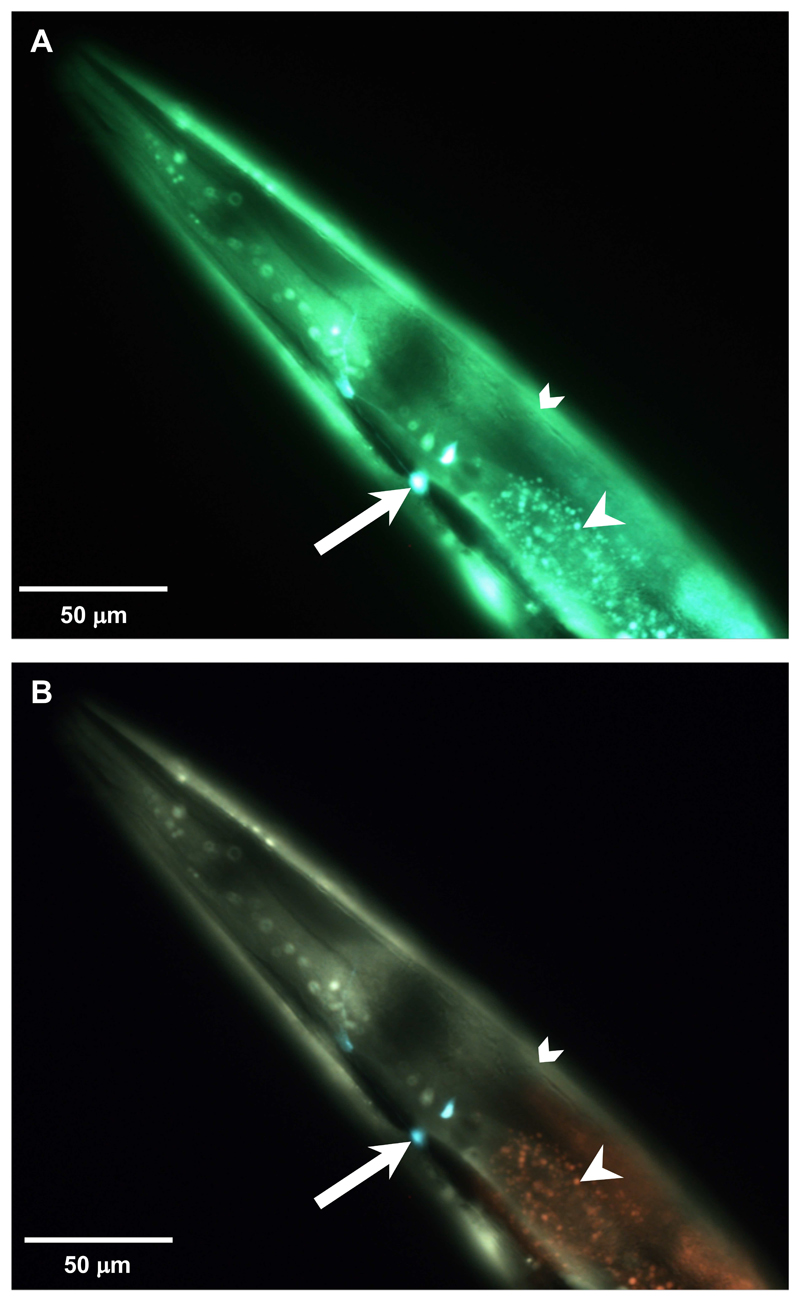

4. Distinguishing YFP, GFP, and autofluorescence in a single image

We wondered whether the triple band filter set would be able to distinguish the fluorescence of YFP and GFP from the intestinal autofluorescence. To test this, we crossed transgenic NL5901 animals that express an α-synuclein-tagged YFP in body wall muscles with the LSD2022 animals, which express GFP in the AIY interneuron pair. Remarkably, YFP in the body wall muscles appears yellowish-green, GFP in the neuron appears aqua marine, and autofluorescence in the intestine appears yellowish (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Triple band filter set allows a clear distinction of YFP from autofluorescence and from GFP.

(A and B) Head region of a double transgenic C. elegans at the eighth day of adulthood that expresses GFP driven by the ttx-3 promoter in the AIY interneuron pair (white arrow) and α-synuclein-tagged YFP driven by the unc-54 promoter in body wall muscles (chevron). The white arrowhead indicates intestinal autofluorescence. A. Imaged with the single band filter set. B. The same animal imaged with the triple band filter set. 1/120 sec exposure time.

Notes

The remaining of the 2% agarose kept at 65 °C in the heat bath can be aliquoted and stored for later re-use. Once the imaging session is completed, we usually aliquot the rest of molten agarose in 1 ml aliquots into 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes for storage at room temperature for at least 2 months. These aliquots can be re-used by placing on a heating block at 95 °C for several minutes and then kept at 65 °C during the imaging session.

To pipet a drop of 2% agarose onto the microscope slide, cut the end of a pipetting tip to allow easier pipetting of the viscous agarose.

In general, C. elegans should not be kept longer than 15 min on the agar pad during an imaging session.

For the transgenic C. elegans line LD1 ldIs007 [Pskn-1::skn-1b/c::gfp], nuclear localization of the fusion protein is preferably scored at the fourth larval stage (L4).

Recipes

-

Agarose pads for C. elegans immobilization and imaging

Add agarose in M9 buffer to obtain a final 2% agarose solution

Heat to dissolve agarose in solution and keep molten by placing it on a heat block at 65 °C

-

M9 buffer (Stiernagle, 2006; He, 2011)

Add 3 g KH2PO4, 7.52 g Na2HPO4, 5 g NaCl, 0.0493 g MgSO4 to 1 L ddH2O, then autoclave

Acknowledgments

We thank Keith Blackwell, Bob Goldstein, Andrew Papp, and Ewald lab members for her helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. The triple band filter set configurations were adapted from the Blackwell lab. We thank Jaegal Shim for the jgIs5 and Ao-Lin Hsu for the EQ87 C. elegans strain. Some C. elegans strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation [PP00P3 163898] to A.C.T. and C.Y.E. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding:

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation [PP00P3 163898] to A.C.T. and C.Y.E.

References

- 1.An JH, Blackwell TK. SKN-1 links C. elegans mesendodermal specification to a conserved oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. 2003;17(15):1882–1893. doi: 10.1101/gad.1107803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop NA, Guarente L. Two neurons mediate diet-restriction-induced longevity in C. elegans. Nature. 2007;447(7144):545–549. doi: 10.1038/nature05904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwell TK, Steinbaugh MJ, Hourihan JM, Ewald CY, Isik M. SKN-1/Nrf, stress responses, and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88(Pt B):290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulin T, Etchberger JF, Hobert O. Reporter gene fusions. Worm Book. 2006:1–23. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.106.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263(5148):802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang WC, Ching TT, Lee HC, Mousigian C, Hsu AL. HSF-1 regulators DDL-1/2 link insulin-like signaling to heat-shock responses and modulation of longevity. Cell. 2012;148(1–2):322–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coburn C, Allman E, Mahanti P, Benedetto A, Cabreiro F, Pincus Z, Matthijssens F, Araiz C, Mandel A, Vlachos M, Edwards SA, et al. Anthranilate fluorescence marks a calcium-propagated necrotic wave that promotes organismal death in C. elegans. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(7):e1001613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ewald CY, Landis JN, Porter Abate J, Murphy CT, Blackwell TK. Dauer-independent insulin/IGF-1-signalling implicates collagen remodelling in longevity. Nature. 2015;519(7541):97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature14021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ewald CY, Hourihan JM, Blackwell TK. Oxidative stress assays (arsenite and tBHP) in Caenorhabditis elegans. Bio-protocol. 2017a;7(13):e2365. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewald CY, Hourihan JM, Bland MS, Obieglo C, Katic I, Moronetti Mazzeo LE, Alcedo J, Blackwell TK, Hynes NE. NADPH oxidase-mediated redox signaling promotes oxidative stress resistance and longevity through memo-1 in C. elegans. Elife. 2017b;6:e19493. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havermann S, Chovolou Y, Humpf HU, Watjen W. Caffeic acid phenethylester increases stress resistance and enhances lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans by modulation of the insulin-like DAF-16 signalling pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He F. Common worm media and buffers. Bio-protocol. 2011;1(7):e55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson ST, Johnson TE. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11(24):1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heppert JK, Dickinson DJ, Pani AM, Higgins CD, Steward A, Ahringer J, Kuhn JR, Goldstein B. Comparative assessment of fluorescent proteins for in vivo imaging in an animal model system. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27(22):3385–3394. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-01-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermann GJ, Schroeder LK, Hieb CA, Kershner AM, Rabbitts BM, Fonarev P, Grant BD, Priess JR. Genetic analysis of lysosomal trafficking in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(7):3273–3288. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Q, D'Amora DR, MacNeil LT, Walhout AJM, Kubiseski TJ. The oxidative stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans requires the GATA transcription factor ELT-3 and SKN-1/Nrf2. Genetics. 2017;206(4):1909–1922. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.198788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kell A, Ventura N, Kahn N, Johnson TE. Activation of SKN-1 by novel kinases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43(11):1560–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim TH, Kim DH, Nam HW, Park SY, Shim J, Cho JW. Tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase regulates collagen secretion in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cells. 2010;29(4):413–418. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon ES, Narasimhan SD, Yen K, Tissenbaum HA. A new DAF-16 isoform regulates longevity. Nature. 2010;466(7305):498–502. doi: 10.1038/nature09184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lapierre LR, De Magalhaes Filho CD, McQuary PR, Chu CC, Visvikis O, Chang JT, Gelino S, Ong B, Davis AE, Irazoqui JE, Dillin A, et al. The TFEB orthologue HLH-30 regulates autophagy and modulates longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2267. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell. 2003;115(4):489–502. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGee MD, Weber D, Day N, Vitelli C, Crippen D, Herndon LA, Hall DH, Melov S. Loss of intestinal nuclei and intestinal integrity in aging C. elegans. Aging Cell. 2011;10(4):699–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monici M. Cell and tissue autofluorescence research and diagnostic applications. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2005;11:227–256. doi: 10.1016/S1387-2656(05)11007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton EA, Lamitina T. Caenorhabditis elegans HSF-1 is an essential nuclear protein that forms stress granule-like structures following heat shock. Aging Cell. 2013;12(1):112–120. doi: 10.1111/acel.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pincus Z, Mazer TC, Slack FJ. Autofluorescence as a measure of senescence in C. elegans: look to red, not blue or green. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8(5):889–898. doi: 10.18632/aging.100936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, Tomancak P. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1463–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robida-Stubbs S, Glover-Cutter K, Lamming DW, Mizunuma M, Narasimhan SD, Neumann-Haefelin E, Sabatini DM, Blackwell TK. TOR signaling and rapamycin influence longevity by regulating SKN-1/Nrf and DAF-16/FoxO. Cell Metab. 2012;15(5):713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. Worm Book. 2006:1–11. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tullet JM, Hertweck M, An JH, Baker J, Hwang JY, Liu S, Oliveira RP, Baumeister R, Blackwell TK. Direct inhibition of the longevity-promoting factor SKN-1 by insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. Cell. 2008;132(6):1025–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Ma X, Li J, Cui X. Peptides from sesame cake extend healthspan of Caenorhabditis elegans via upregulation of skn-1 and inhibition of intracellular ROS levels. Exp Gerontol. 2016;82:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]