ABSTRACT

The HPV vaccine debuted more than ten years ago in the United States and many strategies have been evaluated to increase HPV vaccination rates, which include not only improving current vaccination behaviors but also sustaining these behaviors. Researchers and practitioners from a variety of backgrounds have engaged in this work, which has included efforts directed at public health and government policies, health education and health promotion programs, and clinical and patient-provider approaches, as well as work aimed to respond to and combat anti-HPV vaccination movements in society. Using a previously developed conceptual model to organize and summarize each of these areas, this paper also highlights the need for future HPV vaccine promotion work to adopt a multi-level and, when possible, integrated approach in order to maximize impact on vaccination rates.

KEYWORDS: adolescent health, attitudes toward health, communication, health promotion, human papilloma virus vaccine

Introduction

Genital human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI), with the CDC estimating that more than 90% of men and more than 80% of women will be infected with at least one type of HPV in their lives.1 Genital HPV strains are categorized as low-risk and high-risk, with the low-risk strains known to cause genital warts and the high risk-strains known to cause several types of cancer.2 Virtually all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV, with 70% of cervical cancer cases linked to just two types of HPV – 16 and 18.2

The introduction of the multi-dose HPV vaccine, however, began a new era in STI and cancer prevention. Alex Azar, the deputy secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services at the time, said the approval of this vaccine was “a major step forward in public health protection.”3 However, many in public health and healthcare also expressed caution, noting that it might be challenging to promote a vaccine for STI prevention. The 9-valent HPV vaccine (9vHPV) is the HPV vaccine currently available in the U.S. and the CDC recommends that all children be vaccinated routinely at 11 or 12 years of age; in other words, prior to sexual initiation and at the same visit when the meningococcal (MenACWY) and tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccines are administered.4 Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine on the eve of the vaccine's introduction, Steinbrook noted:

The acceptance of the HPV vaccine — by physicians, parents, preteens, and the public at large — is also uncertain. As with many issues related to sex, people may have strong views. Increased acceptance is likely to require ongoing discussion and educational efforts.5

In the 11 years since this statement, the diffusion of the HPV vaccine has increased, albeit quite slowly. Data from the 2016 National Immunization Survey-Teen indicates that about 56% of 13–17 year old male adolescents and 65% of females have started the HPV vaccine series, with only 38% of males and 50% of females finishing the vaccine series.6 These current vaccination rates fall well below the Healthy People 2020 objective to reach 80% series completion for all adolescents.7 Despite the modest levels of vaccination, we are reaping some public health benefits; comparisons of pre-vaccine and post-vaccine HPV prevalence reveal a 64% decrease of HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 among females 14–19 years of age.8

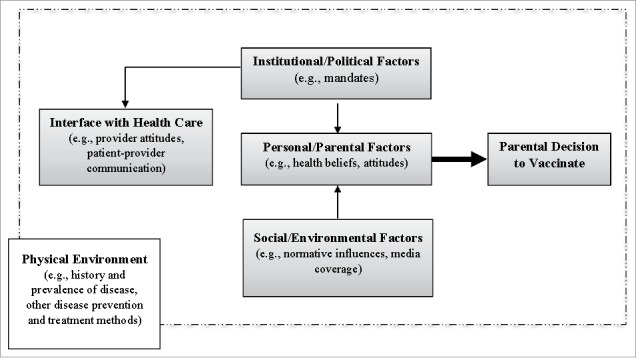

Numerous strategies have been evaluated to increase HPV vaccination rates, to not only improve current vaccination behaviors but also sustain these behaviors. Importantly, the promotion of the HPV vaccine is somewhat unique in a number of ways. First, promotion of this vaccine is complicated in that it is a multi-dose vaccine that is not generally required for school entry, has a broad age range (ages 9–26), and prevents sexually transmitted infections. Second, in addition to public health policies and promotion strategies, there have also been paid advertisement campaigns by Merck, the maker of the Gardasil HPV vaccine, including the well-known “One Less” campaign and the more recent “Did you know?” campaign. While these mass media advertisements have been shown to have an effect on awareness and decision to vaccinate,9 they are not the focus of this review. Instead, we focus on the many efforts directed at public health and government policies, health education and health promotion programs, and clinical and patient-provider approaches, as well as work aimed to respond to and combat anti-HPV vaccination movements in society. Importantly, we have organized this paper according to a previous conceptual model we developed outlining key issues in parental decision-making about child and adolescent vaccination.10 The original article defines the scope of the model in this way:

“when parents consider whether to have their child immunized, their decision or willingness to immunize may be influenced by social-environmental factors, parent-specific or personal factors, the family's interface with the health care system, institutional policies and interventions related to vaccines, and the physical environment of health” (p. 442).

Several years later, the model was critiqued when another scholar argued that it would be improved by including explicit mention of the role of political factors, especially the interplay between government and local/state policies.11 Taking this critique into consideration, the revised model is included here (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Factors affecting parental decisions on childhood/adolescent vaccination.

In this paper, we use this conceptual model to organize our review of strategies and their success in addressing HPV vaccination of adolescents in the United States, and draw attention to potential future intervention approaches for consideration and study.

Institutional and policy factors influencing HPV vaccination

Institutional and policy-based initiatives can and do play a large role in driving uptake of the HPV vaccine. However, this is a relatively complicated area with the need to consider different federal and state initiatives for vaccination, new and changing professional and national disciplinary committees' recommendations and guidelines, and even healthcare-based institutional policies that could affect parental decisions to vaccinate.

School-based policies

In the U.S., perhaps the most effective tool for achieving high vaccination rates involves school entry requirements, often referred to as mandates.12 These requirements, which are determined on a state-by-state basis, have been remarkably successful in improving coverage for many vaccines, including, but not limited to, MenACWY and Tdap.13 Moreover, when exemptions from school entry requirements are easily granted (e.g., on the basis of “personal beliefs”), the result is decreased vaccination rates and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.14,15 Since the introduction of HPV vaccination in the U.S. there has been a good deal of debate around school entry requirements. Intensive efforts to pass legislation in 2006 and 2007, shortly after the HPV vaccine was licensed, led to a backlash in public opinion and a number of critical analyses of these efforts were published.16-20 The first two jurisdictions to pass school entry requirements for HPV vaccine, Virginia and the District of Columbia, enacted legislation that was quite weak, applied only to girls, and had no real enforcement.21 For example, the Virginia HPV vaccination requirement reads as follows:

Effective October 1, 2008, a complete series of 3 doses of HPV vaccine is required for females. The first dose shall be administered before the child enters the 6th grade. After reviewing educational materials approved by the Board of Health, the parent or guardian, at the parent's or guardian's sole discretion, may elect for the child not to receive the HPV vaccine.22

Not surprisingly, when such inherently flawed public health policies are implemented, they have little impact on the intended outcome, HPV vaccination rates.23 While it is difficult to fully evaluate its effects at this point in time, Rhode Island, which has the nation's highest HPV vaccination rates, implemented a stronger, gender neutral school entry requirement in 2015.24 Although enactment of school entry requirements for HPV vaccine is politically challenging and somewhat controversial,25 it remains an important strategy to consider in order to ensure maximum protection against cervical and other HPV-related cancers.

Vaccine policies

Another public policy approach is a reduction in the number of vaccine doses recommended for series completion. With evidence for efficacy of a 2-dose regimen in younger adolescents, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recently changed their recommendation from three to two doses for those who receive the first dose before age 15 years.26 The two doses should be administered six to twelve months apart. This policy change may serve to increase vaccination rates by reducing costs and logistical barriers, and by providing a motivation for initiating vaccination at younger vs. older ages. Furthermore, there is preliminary evidence suggesting that a single dose of HPV vaccine may be sufficient to provide reasonably long-lasting protection.27-29 A future policy shift to a one-dose regimen would likely have a very positive effect on HPV vaccination rates.

Age-based policies

Other public policy initiatives that could impact HPV vaccination rates include implementing a recommendation that vaccination should be initiated at ages 9–10 rather than at ages 11–12 (the vaccine is already licensed down to age 9 years) and harmonizing the recommendations for males and females ages 22–26 years. The earlier initiation of vaccination might help to minimize the association of HPV vaccine with initiation of sexual behavior and may allow for the completion of the two-dose series at the 11–12 year old visit when MenACWY and Tdap are administered. A recent review found that providers typically waited until much later in adolescence, and beyond the target age set by the CDC (11–12 years), to recommend the HPV vaccine to parents and adolescents; this was usually a result of parental preference for waiting to discuss it.30 However, to our knowledge, no research has explicitly examined parent or provider perspectives on the issue of vaccinating at an earlier age.

On the other end of the age spectrum, “catch-up” vaccination is routinely recommended for all women up through age 26, but not for all men. For men ages 22 through 26 years, ACIP only routinely recommends catch-up vaccination for men who have sex with men, transgender persons, and those with immunocompromising conditions.26 These divergent recommendations based on sex add to the complexity of public health messaging and contribute to confusion around HPV vaccination policy.

Provider policies

Another policy approach that could help to improve HPV vaccination rates is implementation of a benchmark that requires providers to achieve a pre-determined level of vaccination in their eligible patients. Health insurance plans that implement such policies can reward providers who reach the designated level and impose consequences on those who fail to achieve the benchmark. Currently, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) issues the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures, which are benchmarks used by many health insurance plans. Included among the HEDIS measures is the expectation that all doses of HPV vaccine be administered by age 13.31

Future directions

In sum, there are a number of institutional and policy strategies to increase HPV vaccination that could have large and lasting effects on uptake rates. Researchers should continue to partner with policy makers to better investigate the potential impact of these policies on actual behavior, as well as how the public may perceive and accept these policies. Gaining support from respected public health and medical organizations like APHA or AMA could also help to increase support for, and realization of, these policy ideas.

Clinical and health care influences on HPV vaccination

A second area in which HPV vaccine promotion has taken place is in the clinical setting, such as primary care clinics, pharmacies, and county health department immunization clinics. With several exceptions (e.g., school-based vaccination programs), most vaccinations take place in such clinical settings, making it an ideal context for promoting HPV vaccine. In this section, we review how parents' and adolescents' interactions with health care providers within the more formal health care system play a role in HPV vaccination behaviors.

Role of provider recommendation

Perhaps not surprisingly, a provider recommendation for HPV vaccination is consistently shown to be one of the most important factors driving vaccination intention and behavior for parents of adolescent girls.32-35 On the other hand, many clinicians do not always make appropriate and timely HPV vaccination recommendations to parents of adolescents, potentially leading to a number of missed opportunities.36-38 For example, providers' quality of HPV vaccine recommendations vary on indicators such as timeliness (i.e., based on patient age), consistency (i.e., using risk-based communication strategies when recommending the vaccine), and urgency (i.e., same day vs. at a later visit).38 While clinicians have provided a number of reasons and rationales for delaying or not recommending the HPV vaccine,30,39 it is clear that interventions are needed at the provider level to equip these clinicians with the confidence and skills to make this important recommendation to parents and patients.

Provider training

Medical educators increasingly recognize that equipping providers with the knowledge and communication skills to promote vaccine acceptance by parents and teens should begin early in professional training of medical students.40 Need for early intervention prior to solidification of negative attitudes toward hesitant or refusing parents was illustrated in a recent study with 132 medical students and pediatric residents.41 Compared to vignettes portraying parents who question evidence- based medical recommendation about pediatric antibiotic use or ear tube placement, a vignette portraying a vaccine- hesitant parent elicited more negative attitudes, less willingness to address parent concern, and a preference to refer rather than continue care. Vaccine-specific curriculums have been developed that target both 3rd year medical students42 and pediatric interns43 and employ a variety of teaching approaches, such as lectures, role-plays, simulated patients, and case-based discussions.

Beyond medical school and residency, there has been limited work in provider training in the clinical setting. One intervention included training providers to talk about HPV vaccination with parents in one of two ways, either as a one-way announcement to parents about the need to vaccinate against HPV or as a conversation/shared-decision making approach in which the parents and clinicians discussed the HPV vaccine.44 Interestingly, the announcement arm of the intervention, which could be seen as a more paternalistic approach, was successful at significantly, though modestly, increasing HPV vaccination initiation in both boys and girls, while the conversation approach did not result in any statistically significant increases. Another approach called Performance Improvement Continuing Medical Education (PI CME) has been used in a variety of clinical settings for different health topics. In the HPV vaccination arena, one intervention utilized a combination of provider education, support to providers, individualized feedback on the providers' vaccination rates, and incentives to improve HPV vaccination.45,46 They found that providers receiving the PI CME program were significantly more likely to vaccinate boys and girls with their first dose and with the follow-up HPV vaccine doses. However, these interventions and others like it can be time and resource intensive and may not be feasible for wide scale dissemination.46

Technology

eHealth technologies provide an opportunity to address HPV vaccination initiation and completion in the clinical setting. Clinical decision support (CDS) aids, usually in the form of reminders in the electronic health record to the provider, are showing some promise in improving vaccination rates.47-50 Usually based on an algorithm of a limited number of variables which combines CDC guidelines and recommendations with several patient demographic variables (e.g., age, sex), the clinician is given a reminder prompt at the time of the visit to discuss and recommend appropriate vaccines.47,48 In two studies which investigated these clinical decision support aids, results showed significantly higher HPV vaccine initiation49 and both higher initiation and completion rates50 for adolescent females. However, in a prospective intervention study, clinician reminder prompts did not increase initiation or series completion of HPV vaccination.51 Despite their promise, CDS programs still have many limitations (e.g., alert fatigue for clinicians, easy ability to override alerts) and more work is needed to maximize the benefit (e.g., developing alert systems that include both clinician and patient roles) that can be gained from this type of intervention.52

Perhaps the most promising application of eHealth is the use of mobile technology, namely text messaging, to prompt parents and their adolescents to begin or continue the HPV vaccine regimen. Those interventions that have incorporated text messaging have mostly targeted the parents of adolescents and included not only prompting parents to initiate the HPV vaccine series with the first dose,53 but also used texting reminders for getting the follow-up doses of the HPV vaccine at the appropriate time intervals.54-56 Text messaging can also be combined with other intervention elements, such as in-person consultation, to increase the efficacy of the intervention.57 In addition to simple reminders, text messages can also contain particular message features, such as educational messages about HPV and cancer, the source of the health threat, or the role of personal agency, to increase parental intention to vaccinate their children.58,59 Text messaging may be a particularly promising area for increasing uptake of dose 1 and timely completion of the second HPV dose, especially given that the Pew Research Center reports that 73% of American adults are text messaging users, sending and receiving an average of 42 texts per day – and that report was done 6 years ago.60 This is also a technology which is widely used by underserved groups (e.g., racial minorities, low income groups) for health information, making it an ideal intervention strategy for reaching those most at risk.61

Finally, a promising area of eHealth technology for parents in clinics utilizes written educational materials or digital technology to deliver HPV vaccination education and promotion programs. For example, in a clinic feasibility study, parents participated in a self-persuasion tablet-based intervention in which they watched a brief HPV and HPV vaccine educational video and then answered questions which prompted them to generate 3 reasons for vaccinating62 Sixty percent of those parents (n = 15) still undecided about vaccination after viewing the video shifted to endorsing vaccination after participating in the self-persuasion tasks.

Future directions

Despite the success of several eHealth or digital intervention studies, it does not appear that these strategies have been widely disseminated or adopted by a critical mass of clinics to increase HPV vaccination. Many of the strategies that fall under this umbrella are newer and reliant on the development of sophisticated technologies and algorithms for tailored messaging and recommendations based on (often changing) clinical guidelines. Work in this area could benefit from further research and dissemination of successful programs, especially given that some of these programs are potentially scalable and have been shown to be relatively cost effective at improving HPV vaccination rates.63 In tandem with exploring and tracking success of eHealth strategies, providers may need continued training to effectively communicate about the HPV vaccine in order to make appropriate recommendations. As previously mentioned, the majority of HPV vaccination happens in the clinical setting, making it an appropriate and opportune context in which to devote resources and attention to increase vaccine uptake.

Social/environmental factors influencing HPV vaccination

In schools and communities across the country, a number of strategies have been implemented to increase HPV vaccine uptake with varying success. In this section, we discuss different HPV vaccination strategies that have addressed the physical environment and relevant normative and social influences in a community to drive behavior.

School-located vaccination programs

A promising approach to increase HPV vaccination access for adolescents in the United States is receipt of vaccination in schools rather than clinical settings. In the United Kingdom and Australia, implementation of school-located HPV vaccination programs has led to rates of HPV vaccine completion among 11-to-12-year-old girls exceeding 80%.64,65 Although the U.S. has a history of school-located vaccination for other vaccines,66,67 few school-based HPV immunization programs have been implemented, due, perhaps, to political factors, public opinion, and logistical challenges.68 Nonetheless, school-based vaccination, when it can be implemented, may be a viable approach to increase HPV vaccination rates, especially in underserved populations.69

On the other hand, school-located vaccination presents several challenges that must be addressed in any future interventions. Reimbursement remains a consideration with school-located vaccination because schools may not have a mechanism to bill insurance providers and payment for school-located vaccination could be denied by insurers as an out-of-network service.70,71 Other barriers identified in one HPV school located intervention are limitations that may be imposed by state laws and school administrations such as requirements for parents to consent and accompany students for vaccination.72 Parents may never receive consent forms from children, especially middle school aged children,73 and may not be able to accompany students due to work or transportation barriers. Future interventions should consider opt-out consent processes and/or eliminating requirements for parental accompaniment. Additionally, it may be beneficial to consider including Tdap and MenACWY with any school-based HPV vaccine to lessen any resistance to the HPV vaccine given that all three vaccines can be administered at the same age.72 Obtaining buy-in from the local health department and school administrators is critical to increase participation in school-located vaccination because of the messaging and education that they can provide to children and parents about the vaccine. Other considerations for school-located vaccination include vaccination storage, administration, and documentation.

Community-based interventions

Community-based interventions have the potential to increase demand for vaccination. Although several community-based patient education interventions have measured acceptability, attitudes, and intention towards HPV vaccination among adolescents and their parents, few have measured vaccination uptake in adolescent populations.74 Patient navigators and social marketing campaigns show promise in increasing HPV vaccination uptake in the community setting. In one study, adolescents who received education from patient navigators were significantly more likely to receive recommended adolescent vaccines than those who did not.75 Social marketing campaigns seem to demonstrate some effectiveness, with one study showing partial success at driving vaccine uptake in two of four rural counties.76 Despite promise in a few areas, little work has compared different intervention strategies to identify what may be the most effective, including cost-effectiveness.

The use of mass media and digital technologies to deliver interventions is also a promising area. It is well documented that people have difficulty appreciating small safety risks, such as those posed by HPV vaccine side effects. In an online intervention, provision of information comparing HPV vaccine safety to the risk of physical harm posed by a common childhood activity—team sports participation in soccer or basketball— actually improved mothers' willingness to vaccinate their 9–13 year old children.77 Communicative strategies like these, which could consider other vaccine-youth activity comparisons, might help more parents appreciate the very small safety risks posed by HPV vaccine. Although other types of patient education interventions have not measured HPV vaccination uptake among adolescents, DVD and web-based communication approaches could potentially increase HPV vaccination. A DVD-based intervention showed promise in helping Latino and Korean Americans make an informed HPV vaccination decision for their children.78 A web-based program that was tested in adult college students, but not adolescents or their parents, resulted in significantly more positive attitudes in the website group at the end of the intervention.79 Research efforts are expanding on this promising approach by evaluating web-based approaches to reach parents and adolescents with informative and engaging messages about HPV vaccination.80,81 DVDs and web-based programs are an affordable way to communicate to a large group of people and could be developed to target cultural factors that limit vaccination uptake in underserved communities.

Future directions

Overall, more research is needed to determine the best strategies for interventions to increase HPV vaccination access and community demand, and specifically, these interventions should target underserved populations who may be most at risk from HPV-related cancers. More research is necessary to demonstrate whether HPV school-located vaccination is cost effective and feasible. Multiple strategies, such as school-located vaccination to increase access and a DVD to increase community demand, hold promise, but research is needed to identify which components of a multi-faceted approach may best serve these communities. In addition, interventions may have more reach and be more cost effective if they can target multiple behaviors; for example, HPV vaccination could be combined with other vaccinations to increase uptake of multiple immunizations.

Countering the anti-HPV vaccine rhetoric

Environmental and personal/parental factors influencing HPV vaccination

In today's media-saturated world where ideas and stories, regardless of truth, can quickly garner a great deal of attention, any strategy aimed at promoting the HPV vaccine must also take into account anti-vaccination sentiments and messaging. As long as there have been vaccines, there has been resistance to their use; this is of course one of the main reasons that government and institutional policies have been needed to ensure high levels of vaccination in the public and one of the main arguments for implementing school-entry requirements.82 The HPV vaccine fortunately has been immune from the misconception and public conversation around the myth that vaccines cause autism, as much of that debate is centered on infant and early childhood vaccines. However, it has come with its own controversies, including the idea of risk compensation related to increased sexual activity and safety and risks associated with such a “new” vaccine. In this section, we review how the media coverage and public conversations about HPV vaccination contributes to an environment where parents are often left with negative beliefs about the vaccination, as well as highlight work that has sought to address these parental concerns.

Risk compensation

One reason behind opposition to the HPV vaccine was the fear that it would promote earlier sexual initiation or increased sexual activity among the adolescents who received the vaccine.83 Because HPV is a sexually transmitted infection, some parents voiced the opinion that vaccinating children would be equivalent to giving them permission to engage in sexual activity.84,85 Media coverage of the HPV vaccine echoed these concerns, with many newspaper articles86,87 and online news articles88 pushing these ideas. In addition, some religious groups89 and conservative social and political groups90,91 have voiced strong objections to vaccinating girls so young against an STI. Despite this, a recent systematic review of 20 research studies investigating this issue found no evidence for risk compensation following HPV vaccination.92

Safety and vaccine side effects

Another concern that was expressed about HPV vaccine was that it was too “new” and therefore potentially unsafe, despite conclusive research that HPV vaccination is safe and well-tolerated.93,94 A content analysis of U.S. and Canadian newspapers found that while stories did mention the threat of HPV-related disease (e.g., cervical cancer), they often also included “fright factor” messages about HPV vaccine.95 These messages included doubts about the long-term efficacy and safety of the vaccine, as well as the idea that the vaccine was mostly being promoted because of lobbying by pharmaceutical companies, not because it had health benefits. For online coverage, more than 50% of Youtube videos about HPV vaccine were found to be negative in tone; interestingly, these negative videos had more “likes” than positive or ambiguous videos.96

Negative ideas and fears are exacerbated when prominent leaders, like politicians, repeat anecdotes not based in fact to the media. Michelle Bachman, a candidate for the 2012 Republican Presidential Primary, was a particularly outspoken opponent of HPV vaccination. In an interview on the Today Show, she contributed to the vaccine safety and side effect fears by recounting the following story of a mother who came up to her at a rally:

She told me that her little daughter took that vaccine, that injection. And she suffered from mental retardation thereafter…This is the very real concern and people have to draw their own conclusions.97

Her false claim was subsequently refuted by the American Academy of Pediatrics, but statements like hers can remain influential and damaging to efforts at cancer prevention through vaccination. Researchers are increasingly recognizing the importance of not only the role of media in influencing clinical decisions like vaccination, but also the role of everyday interpersonal communication within social networks.98 For example, one study looked at parents' social networks (e.g., friends, fellow parents, healthcare providers) and found that those parents less willing to vaccinate had large social networks of people telling them to not conform to vaccination guidelines (e.g., on time vaccination).99 In addition they tended to consulting more sources of information (e.g., internet, magazine) that also promoted non-adherence to recommended vaccination schedules.99 In other words, mass/public communication about vaccination and interpersonal communication about vaccination go hand-in-hand. While this study was specifically examining parents of young children, it's possible these same patterns exist in parents of older children although more research is needed in this area. More broadly, we know that about 20 percent of individuals caring for loved ones (e.g., parents of children) have gone onto social media sites to gather health information and 38% of them have gone on social media sites to specifically consult others' reviews of medical products (e.g., drugs, vaccines).100 In sum, the role of various mass media and interpersonal influences (and in the case of social media, both) is important in parents' vaccination decisions, suggesting the need to devote more time and attention to not only better understanding the effects of these influences, but also how to account for them in vaccination promotion work.

Work addressing anti-vaccine messaging

Public opposition to vaccines in any form, whether individual stories of patients with claims of adverse side effects or larger initiatives aimed at discounting the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, are important because it can influence individuals' intentions and behaviors to vaccinate. In an experiment in which college students were exposed to either a positive or negative blog post about HPV vaccination, those in the negative group reported lower perceived vaccine efficacy and safety, more negative attitudes, and lower intentions to vaccinate compared to the control and positive blog groups.101 Writing about recent anti-HPV vaccine sentiments, some scholars advise that “the infectious disease and oncology community should be aware of these [stories and ideas in the media]…not corroborated by the evidence base, and they must be able to communicate this to patients and the general public.”102 In other words, not only must we be designing and implementing health promotion programs to encourage vaccination, but practitioners, public health officials, and health communication specialists must also incorporate communication strategies to counter anti-vaccine messaging and sentiments in the general public.

Scholars in health communication have begun to address this need with respect to HPV vaccination. In a study using inoculation messaging techniques, unvaccinated adult individuals who were exposed to messages that inoculated them against attacks on the HPV vaccine or attacks on vaccines in general were less vulnerable to these attack messages in a video experiment compared to the control condition.103 Applying sound communication principles, such as inoculation theory, could be an effective method for countering anti-HPV vaccine sentiments. However, to our knowledge, no research examining this strategy with parents of adolescents has been done. In addition, continued surveillance of public and media concerns circulating in the news and popular press is important in order to inform what informational gaps should be addressed with public health education and health promotion strategies.

Future directions

Unfortunately, as Dube´ and colleagues note, there are “few, if any, public health strategies [that] have effectively and long-lastingly succeeded in countering anti-vaccination movements”,82 suggesting a need for renewed attention and innovative strategizing to address vaccine resistance in the general public in lasting ways. Efforts to combat anti-HPV vaccine messaging is an area where health communication and persuasion scholars may be particularly adept at developing intervention strategies for counter-messaging. For example, the HPV vaccine promotion community may benefit from a well-known or celebrity champion (e.g., a celebrity endorsement) as part of the overall strategy for combating anti-vaccine sentiments.104 More rigorous evaluation of which targeted messaging strategies actually drive vaccine acceptance and uptake for vaccine-hesitant individuals can help drive success in this area.105 Perhaps most important is that anyone working on increasing HPV vaccine uptake – whether in the clinic, state or federal government, community, schools, or media-based work – must take into account that parents' decision-making around this vaccine may be shadowed by personal beliefs such as the sexually transmitted nature of HPV and safety concerns about the vaccine itself.

Conclusion

This review highlights some of the major strategies that have been used to promote HPV vaccination, focusing specifically on policy, clinical training and interventions, community and school-based programs, and an increased awareness of the need to counter anti-vaccine rhetoric. In addition, we draw attention to promising areas for future policy and research efforts in key areas, many of which are consistent with those identified during the 2016 meeting of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.106 Researchers, practitioners, politicians, educators, and pro-vaccination groups are making great strides in increasing the HPV vaccination rate, but there is much progress that remains to be made.

Moving forward, it is essential to recognize that no single strategy or focus will lead to success. Instead, we should work simultaneously on multiple levels (e.g., public health policy, mass media communication, clinical practice, and health education) to ensure that we move towards the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% HPV vaccine series completion. The factors within the conceptual model used to guide our analysis should not be seen as separate parts, but rather as individual pieces of the larger puzzle for increasing HPV vaccination and reducing HPV-related disease. We challenge those in the field to begin working to better integrate multiple approaches for maximum success, something echoed by other scholars as well.107

In fact, most public health issues benefit from a, multi-level, integrated approach. For example, recent statistics show smoking rates in the United States are at an all-time low, which the CDC credits to a variety of “strategies proven to work…like funding tobacco control programs at the CDC-recommended levels, increasing prices of tobacco products, implementing and enforcing comprehensive smoke-free laws, and sustaining hard-hitting media campaigns.”108 This example illustrates that over time and with sustained efforts on multiple fronts, significant and sustained population health behavior change is possible. In addition, an integrated, multi-faceted approach to address vaccination promotion and vaccine concerns also maximizes potential success because a “one size fits all” intervention approach will never address all concerns nor be equally effective with all people.105 This is particularly true for the U.S., which does not have a national health insurance system or the ability to implement uniform national HPV vaccination policies across states and jurisdictions.

But what does this look like for HPV vaccination? Ultimately, it will require integrated efforts to: 1) influence sound public health policy; 2) develop effective media messaging strategies that incorporate health promotion and education as well as counter-messaging for anti-vaccination rhetoric; 3) evaluate and implement strong clinic-based communication and support systems; and 4) minimize logistical barriers in order to maximize HPV vaccination rates and protect our children from the pain, suffering, and expenses associated with HPV-related diseases. We can now promote this vaccine as important for both sexes and for several types of cancer, which may help the general public support HPV vaccine as an incredible public health innovation. While some individual puzzle pieces are in place for increasing HPV vaccine uptake in our country, the next step is putting these pieces together in a comprehensive approach to educate and persuade parents to vaccinate, thereby increasing uptake of this life-saving vaccine.

Funding Statement

Erika Biederman's work on this paper was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA117865.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Chesson HW, Dunne EF, Hariri S, Markowitz LE. The estimated lifetime probability of acquiring human papillomavirus in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(11):660–4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000193. PMID:25299412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute HPV and Cancer. 2015. [accessed 2017September17]. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-fact-sheet#q2.

- 3.Rubin R. First-ever cancer vaccine approved. USA Today 2006 June 9 [accessed 2017September17]. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/2006-06-08-cervical-cancer-vaccine_x.htm.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016 HPV Vaccine Recommendations 2016. December 15 [accessed 2017September17]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html.

- 5.Steinbrook R. The potential of human papillomavirus vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1109–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058305. PMID:16540608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Fredua B, Williams CL, Meyer SA, Stokley S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:874–82. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6633a2. PMID:28837546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – Office of Disease Prevention and a Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020: Immunization and infectious diseases. 2017. [accessed 2017September17]. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives.

- 8.Markowitz LE, Liu G, Hariri S, Steinau M, Dunne EF, Unger ER. Prevalence of HPV after introduction of the vaccination program in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016; 137(3):e20151968. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1968. PMID:26908697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grantham S, Ahern L, Connolly-Ahern C. Merck's One Less Campaign: using risk message frames to promote the use of Gardasil® in HPV prevention. Comm Res Rep. 2011;28(4):318–26. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2011.616243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sturm LA, Mays RM, Zimet GD. Parental beliefs and decision making about child and adolescent immunization: from polio to sexually transmitted infections. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(6):441–452. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200512000-00009. PMID:16344662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callreus T. Perceptions of vaccine safety in a global context. ACTA Paediatrica. 2010;99(2):166–171. PMID:19889101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orenstein WA, Hinman AR. The immunization system in the United States — The role of school immunization laws. Vaccine. 1999;17(Supplement 3):S19–S24. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00290-X. PMID:10559531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bugenske E, Stokley S, Kennedy A, Dorell C. Middle school vaccination requirements and adolescent vaccination coverage. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):1056–63. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2641. PMID:22566425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omer SB, Pan WY, Halsey NA, Stokley S, Moulton LH, Navar AM, Pierce M, Salmon DA. Nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements: secular trends and association of state policies with pertussis incidence. JAMA. 2006; 296(14):1757–63; doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1757. PMID:17032989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atwell JE, Van Otterloo J, Zipprich J, Winter K, Harriman K, Salmon DA, Halsey NA, Omer SB. Nonmedical vaccine exemptions and pertussis in California, 2010. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):624–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colgrove J. The ethics and politics of compulsory HPV vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2389–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068248. PMID:17151362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haber G, Malow RM, Zimet GD. The HPV vaccine mandate controversy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007; 20(6):325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2007.03.101. PMID:18082853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart AM. Mandating HPV vaccination — private rights, public good. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1998–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc071068. PMID:17494936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vamos CA, McDermott RJ, Daley EM. The HPV vaccine: framing the arguments FOR and AGAINST mandatory vaccination of all middle school girls. J Sch Health. 2008;78(6):302–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00306.x. PMID:18489462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opel DJ, Diekema DS, Marcuse EK. A critique of criteria for evaluating vaccines for inclusion in mandatory school immunization programs. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e504–e10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3218. PMID:18676536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart A. Childhood vaccine and school entry laws: the case of HPV vaccine. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(6):801–3. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300617. PMID:19711662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virginia Department of Health School and Day Care Minimum Immunization Requirements. 2017. [accessed 2017September17]. http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/immunization/requirements/.

- 23.Perkins RB, Lin M, Wallington SF, Hanchate AD. Impact of school-entry and education mandates by states on HPV vaccination coverage: analysis of the 2009–2013 National Immunization Survey-Teen. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1615–22. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1150394. PMID:27152418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhode Island Department of Health Immunization Information for Schools and Child Care Workers. 2017. [accessed 2017September17]. http://www.health.ri.gov/immunization/for/schools/.

- 25.National Conference of State Legislatures HPV Vaccine: State Legislation and Statutes. 2017. [accessed 2017September17]. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/hpv-vaccine-state-legislation-and-statutes.aspx.

- 26.Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination — updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1405–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5. PMID:27977643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreimer AR, Struyf F, Del Rosario-Raymundo MR, Hildesheim A, Skinner SR, Wacholder S, Garland SM, Herrero R, David M-P, Wheeler CM, et al.. Efficacy of fewer than three doses of an HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: combined analysis of data from the Costa Rica Vaccine and PATRICIA trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):775–86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00047-9. PMID:26071347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuschieri K, Kavanagh K, Moore C, Bhatia R, Love J, Pollock KG. Impact of partial bivalent HPV vaccination on vaccine-type infection: a population-based analysis. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(11):1261–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.97. PMID:27115467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sankaranarayanan R, Prabhu PR, Pawlita M, Gheit T, Bhatla N, Muwonge R, Nene BM, Esmy PO, Joshi S, Poli URR, et al.. Immunogenicity and HPV infection after one, two, and three doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine in girls in India: a multicentre prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):67–77. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00414-3. PMID:26652797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilkey MB, McRee A-L.. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016; 12(6):1454–68. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1129090. PMID:26838681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NCQA HEDIS® & Performance Measurement. 2017. [accessed 2017September17] http://www.ncqa.org/hedis-quality-measurement.

- 32.Mohammed KA, Vivian E, Loux TM, Arnold LD. Factors associated with parents' intent to vaccinate adolescents for human papillomavirus: findings from the 2014 National Immunization Survey–Teen. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E45. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160314. PMID:28595031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahman M, Laz TH, McGrath CJ, Berenson AB. Provider recommendation mediates the relationship between parental human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine awareness and HPV vaccine initiation and completion among 13-to 17-year-old U.S. adolescent children. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54(4):371–5. doi: 10.1177/0009922814551135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ylitalo KR, Lee H, Mehta NK. Health care provider recommendation, human papillomavirus vaccination, and race/ethnicity in the US National Immunization Survey. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):164–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300600. PMID:22698055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sturm L, Donahue K, Kasting M, Kulkarni A, Brewer NT, Zimet GD. Pediatrician-parent conversations about human papillomavirus vaccination: an analysis of audio recordings. J Adolesc Health. 2017; 61(2):246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.006. PMID:28455129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vadaparampil ST, Malo TL, Sutton SK, Ali KN, Kahn JA, Casler A, Salmon D, Walkosz B, Roetzheim RG, Zimet GD, et al.. Missing the target for routine human papillomavirus vaccination: consistent and strong physician recommendations are lacking for 11–12 year old males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(10):1435–46. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1294. PMID:27486020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieger JL, Katz ML, Kam JA, Roberto A. Appalachian and non-Appalachian pediatricians' encouragement of the human papillomavirus vaccine: implications for health disparities. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(1):e19–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.005. PMID:21907591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, Hall ME, Brewer NT. quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1673–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0326. PMID:26494764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perkins RB, Clark JA, Apte G, Vercruysse JL, Sumner JJ, Wall-Haas CL, Rosenquist AW, Pierre-Joseph N. missed opportunities for hpv vaccination in adolescent girls: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e666–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0442. PMID:25136036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown AEC, Suryadevara M, Welch TR, Botash AS “Being Persistent without Being Pushy”: student reflections on vaccine hesitancy. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2017;7(1):59–70. doi: 10.1353/nib.2017.0018. PMID:28713146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Philpott SE, Witteman HO, Jones KM, Sonderman DS, Julien A-S, Politi MC. Clinical trainees' responses to parents who question evidence-based recommendations. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(9):1701–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.002. PMID:28495389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coleman A, Lehman D. A flipped classroom and case-based curriculum to prepare medical students for vaccine-related conversations with parents. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2017;13(10582). doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morhardt T, McCormack K, Cardenas V, Zank J, Wolff M, Burrows H. Vaccine curriculum to engage vaccine-hesitant families: didactics and communication techniques with simulated patient encounter. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2016;12(10400). doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161764. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1764. PMID:27940512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorman T, Miller BM. Continuing medical education: the link between physician learning and health care outcomes. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1339. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182308d49. PMID:22030638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine 2015;33(9):1223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.021. PMID:25448095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaspers MWM, Smeulers M, Vermeulen H, Peute LW. Effects of clinical decision-support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a synthesis of high-quality systematic review findings. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(3):327–34. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000094. PMID:23807361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stockwell MS, Fiks AG. Utilizing health information technology to improve vaccine communication and coverage. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1802–11. doi: 10.4161/hv.25031. PMID:21422100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fiks AG, Grundmeier RW, Mayne S, Song L, Feemster K, Karavite D, Hughes CC, Massey J, Keren R, Bell LM, et al.. Effectiveness of decision support for families, clinicians, or both on HPV vaccine receipt. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1114–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruffin MT, Plegue MA, Rockwell PG, Young AP, Patel DA, Yeazel MW. Impact of an electronic health record (EHR) reminder on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine initiation and timely completion. J Am Borad Fam Med. 2015;28(3):324–33. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.03.140082. PMID:23650297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szilagyi PG, Serwint JR, Humiston SG, Rand CM, Schaffer S, Vincelli P, Dhepyasuwan N, Blumkin A, Albertin C, Curtis CR. effect of provider prompts on adolescent immunization rates: a randomized trial. Acad Pediatr. 2015; 15(2):149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.006. PMID:25748976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roshanov PS, Fernandes N, Wilczynski JM, Hemens BJ, You JJ, Handler SM, Nieuwlaat R, Souza NM, Beyene J, Spall HGCV, et al.. Features of effective computerised clinical decision support systems: meta-regression of 162 randomised trials. BMJ. 2013;346:f657. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f657. PMID:23412440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rand CM, Brill H, Albertin C, Humiston SG, Schaffer S, Shone LP, Blumkin AK, Szilagyi PG. Effectiveness of centralized text message reminders on human papillomavirus immunization coverage for publicly insured adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(5):S17–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.273. PMID:25863549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kharbanda EO, Stockwell MS, Fox HW, Andres R, Lara M, Rickert VI. Text message reminders to promote human papillomavirus vaccination. Vaccine. 2011; 29(14):2537–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.065. PMID:2400295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matheson EC, Derouin A, Gagliano M, Thompson JA, Blood-Siegfried J. Increasing HPV vaccination series completion rates via text message reminders. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(4):e35–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2013.09.001. PMID:21300094.27836533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rand CM, Vincelli P, Goldstein NP, Blumkin A, Szilagyi PG. Effects of phone and text message reminders on completion of the human papillomavirus vaccine series. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(1):113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.011. PMID:27836533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aragones A, Bruno DM, Ehrenberg M, Tonda-Salcedo J, Gany FM. Parental education and text messaging reminders as effective community based tools to increase HPV vaccination rates among Mexican American children. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:554–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.06.015. PMID:26844117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee HY, Koopmeiners JS, McHugh J, Raveis VH, Ahluwalia JS. mHealth pilot study: text messaging intervention to promote HPV vaccination. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(1):67–76. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.40.1.8. PMID:26685815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGlone MS, Stephens KK, Rodriguez SA, Fernandez ME. Persuasive texts for prompting action: agency assignment in HPV vaccination reminders. Vaccine. 2017;35(34):4295–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.080. PMID:28673483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith A. 2011 Americans and Text Messaging. Pew Research Center; 2011 September 19 [accessed 2017Sepetember 17]. http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/09/19/americans-and-text-messaging.

- 61.Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baldwin AS, Denman DC, Sala M, Marks EG, Shay LA, Fuller S, Persaud D, Lee SC, Skinner CS, Wiebe DJ, et al.. Translating self-persuasion into an adolescent HPV vaccine promotion intervention for parents attending safety-net clinics. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):736–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.11.014. PMID:24161087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noar SM, Harrington NG, eHealth applications: promising strategies for behavior change. New York: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Public Health England Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage in adolescent females in England: 2015/2016. 2016. [accessed 2017September20]. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/578729/HPV_vaccination-_2015-16.pdf.

- 65.National HPV Vaccination Program Register HPV vaccination coverage by dose number (Australia) for females by age group in mid 2014. 2017. [accessed 2017September20]. http://www.hpvregister.org.au/research/coverage-data/HPV-Vaccination-Coverage-by-Dose-2014.

- 66.Deuson RR, Hoekstra EJ, Sedjo R, Bakker G, Melinkovich P, Daeke D, Hammer AL, Goldsman D, Judson FN. The Denver school-based adolescent hepatitis B vaccination program: a cost analysis with risk simulation. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(11):1722–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.11.1722. PMID:10553395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cawley J, Hull HF, Rousculp MD. Strategies for Implementing school‐located influenza vaccination of children: a systematic literature review. J Sch Health. 2010;80(4):167–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00482.x. PMID:20433642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nodulman JA, Starling R, Kong AS, Buller DB, Wheeler CM, Woodall WG. Investigating stakeholder attitudes and opinions on school-based human papillomavirus vaccination programs. J Sch Health. 2015;85(5):289–98. doi: 10.1111/josh.12253. PMID:25846308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vanderpool RC, Breheny PJ, Tiller PA, Huckelby CA, Edwards AD, Upchurch KD, Phillips CA, Weyman CF. Implementation and evaluation of a school-based human papillomavirus vaccination program in rural Kentucky. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 49(2):317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.001. PMID:26190806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Daley MF, Kempe A, Pyrzanowski J, Vogt TM, Dickinson LM, Kile D, Fang H, Rinehart DJ, Shlay JC. School-located vaccination of adolescents with insurance billing: cost, reimbursement, and vaccination outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2014; 54(3):282–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.011. PMID:24560036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hayes KA, Entzel P, Berger W, Caskey RN, Shlay JC, Stubbs BW, Smith JS, Brewer NT. Early lessons learned from extramural school programs that offer HPV vaccine. J Sch Health. 2013;83(2):119–126. doi: 10.1111/josh.12007. PMID:23331272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stubbs BW, Panozzo CA, Moss JL, Reiter PL, Whitesell DH, Brewer NT. Evaluation of an intervention providing HPV vaccine in schools. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(1):92–102. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.1.10. PMID:24034684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cawley J, Hull HF, Rousculp MD. Strategies for implementing school‐located influenza vaccination of children: a systematic literature review. J Sch Health. 2010;80(4):167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00482.x. PMID:20433642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fu LY, Bonhomme L-A, Cooper SC, Joseph JG, Zimet GD. Educational interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptance: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014;32(17):1901–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.091. PMID:24530401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Szilagyi PG, Humiston SG, Gallivan S, Albertin C, Sandler M, Blumkin A. Effectiveness of a citywide patient immunization navigaotr program on improving adolescent immunizations and preventive care visit rates. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(6):547–53. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.73. PMID:21646588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cates JR, Shafer A, Diehl SJ, Deal AM. Evaluating a county-sponsored social marketing campaign to increase mothers' initiation of HPV vaccine for their preteen daughters in a primarily rural area. Soc Mar Q. 2011;17(1):4–26. doi: 10.1080/15245004.2010.546943. PMID:21804767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Donahue K, Hendrix K, Sturm L, Zimet G. Provider communication and mothers' willingness to vaccinate against HPV and influenza: a randomized health messaging trial. Acad Pediatr. 2017, in press. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.07.007. PMID:28754504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Valdez A, Stewart SL, Tanjasari SP, Levy V, Garza A. Design and efficacy of a multilingual, multicultural HPV vaccine education intervention. J Commun Healthc. 2015;8(2):106–18. doi: 10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000015. PMID:27540413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Doherty K, Low KG. The effects of a web-based intervention on college students' knowledge of human papillomavirus and attitudes toward vaccination. Int J Sex Health. 2008;20(4):223–32. doi: 10.1080/19317610802411177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Starling R, Nodulman JA, Kong AS, Wheeler CM, Buller DB, Woodall WG. Beta-test results for an HPV information web site: GoHealthyGirls.org – increasing HPV vaccine uptake in the United States. J Consum Health Internet. 2014;18(3):226–37. doi: 10.1080/15398285.2014.931771. PMID:25221442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Starling R, Nodulman JA, Kong AS, Wheeler CM, Buller DB, Woodall WG. Usability testing of an HPV information website for parents and adolescents. Online J Commun Media Technol. 2015;5(4):184–203. PMID:26594313 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dubé E, Vivion M, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14(1):99–117. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.964212. PMID:25373435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zimet GD, Rosberger Z, Fisher WA, Perez S, Stupiansky NW. Beliefs, behaviors and HPV vaccine: correcting the myths and the misinformation. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):414–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.05.013. PMID:23732252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(2):107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013. PMID:17628649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marlow LA, Forster AS, Wardle J, Waller J. Mothers' and adolescents' beliefs about risk compensation following HPV vaccination. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(5):446–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.09.011. PMID:19380091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Casciotti DM, Smith KC, Tsui A, Klassen AC. Discussions of adolescent sexuality in news media coverage of the HPV vaccine. J Adolesc. 2014;37(2):133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.004. PMID:24439619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Forster A, Wardle J, Stephenson J, Waller J. Passport to promiscuity or lifesaver: press coverage of HPV vaccination and risky sexual behavior. J Health Commun. 2010;15(2):205–17. doi: 10.1080/10810730903528066. PMID:20390987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Habel MA, Liddon N, Stryker JE. The HPV vaccine: a content analysis of online news stories. J Womens Health. 2009;18(3):401–7. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Touyz SJJ, Touyz LZG. The kiss of death: HPV rejected by religion. Curr Oncol. 2013;20(1):e52–e3. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1186. PMID:23443919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Casper MJ, Carpenter LM. Sex, drugs, and politics: the HPV vaccine for cervical cancer. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30(6):886–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01100.x. PMID:18761509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gabriel T, Grady D. In Republican race, a heated battle over the HPV vaccine. The New York Times. 2011. September 14;A16. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kasting ML, Shapiro GK, Rosberger Z, Kahn JA, Zimet GD. Tempest in a teapot: a systematic review of HPV vaccination and risk compensation research. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1435–50. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1141158. PMID:26864126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stokley S, Jeyarajah J, Yankey D, Cano M, Gee J, Roark J, Curtis R, Markowitz L. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents, 2007–2013, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006-2014–United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(29):620–4. PMID:25055185 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Van Damme P, Olsson SE, Block S, Castellsague X, Gray GE, Herrera T, Huang L-M, Kim DS, Pitisuttithum P, Chen J, et al.. Immunogenicity and safety of a 9-valent HPV vaccine. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e28–39. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3745. PMID:26101366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Abdelmutti N, Hoffman-Goetz L. Risk messages about HPV, cervical cancer, and the HPV vaccine Gardasil: a content analysis of Canadian and U.S. national newspaper articles. Women Health. 2009;49(5):422–40. doi: 10.1080/03630240903238776. PMID:19851946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Briones R, Nan X, Madden K, Waks L. When vaccines go viral: an analysis of HPV vaccine coverage on YouTube. Health Commun. 2012;27(5):478–85. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.610258. PMID:22029723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hensley S. Pediatricians fact-check Bachmann's bashing of HPV vaccine. National Public Radio (NPR). 2011. September 13. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Head KJ, Bute JJ. The influence of everyday interpersonal communication on the medical encounter: an extension of street's ecological model. Health Commun. 2017;(in press). doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1306474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Brunson EK. The impact of social networks on parents' vaccination decisions. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1397–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2452. PMID:23589813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fox S. The social life of health information. Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project. 2011. http://www.pewinternet.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nan X, Madden K. HPV vaccine information in the blogosphere: how positive and negative blogs influence vaccine-related risk perceptions, attitudes, and behavioral intentions. Health Commun. 2012;27(8):829–36. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.661348. PMID:22452582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Head MG, Wind-Mozley M, Flegg PJ. Inadvisable anti-vaccination sentiment: human papilloma virus immunisation falsely under the microscope. npj Vaccines. 2017;2(1):6–7. doi: 10.1038/s41541-017-0004-x. PMID:29263867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wong NCH. “Vaccinations are Safe and Effective”: inoculating positive hpv vaccine attitudes against antivaccination attack messages. Commun Rep. 2016;29(3):127–38. doi: 10.1080/08934215.2015.1083599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gowda C, Dempsey AF. The rise (and fall?) of parental vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1755–62. doi: 10.4161/hv.25085. PMID:23744504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041. PMID:25896385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reiter PL, Gerend MA, Gilkey MB, Perkins RB, Saslow D, Stokley S, Tiro JA, Zimet GD, Brewer NT. Advancing HPV vaccine delivery: 12 priority research gaps. Acad Pediatr. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fernández ME, Allen JD, Mistry R, Kahn JA. Integrating clinical, community, and policy perspectives on human papillomavirus vaccination. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31(1):235–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103609. PMID:20001821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Adult cigarette smoking rate overall hits all-time low. 2014. November 26 [accessed 2017September20]. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p1126-adult-smoking.html. [Google Scholar]