ABSTRACT

Vaccination has been identified many decades ago as an effective means to prevent several diseases. However, in France, there is an emergence of vaccine hesitancy, that has caused a reduction of vaccination coverage rates. This issue reduces the effectiveness of the immunization process, and represents a real threat to public health that should be urgently addressed. The purpose of this review is to present actions that have been taken to fight against vaccine hesitancy and thus enhance vaccine uptake. The results indicate that different strategies have been proposed to reach this goal, mainly by vaccination campaigns. These findings highlight the strong implication of national health authorities and the medical staff of hospitals and health-care centers. However, actions implemented should be part of a long-term approach, and further studies are required to identify the most effective strategies to address vaccine hesitancy.

KEYWORDS: vaccine hesitancy, vaccine uptake, vaccine acceptance, vaccination program, France, infectious disease, vaccinology

Introduction

Vaccination is considered as one of the greatest advances in health in the 20th century.1 It is known as the most effective means to prevent diseases, with an interesting cost-effectiveness ratio, and has notably led to the eradication of diseases such as smallpox and poliomyelitis, but has also lessened the burden of Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) and measles.2 Despite this huge success, the coverage rates in some European countries are currently insufficient to ensure herd immunity, as vaccination rates are below the coverage threshold of 95% recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for some vaccines.3

The negative perceptions towards vaccination have increased over the past two decades, and have led to an emerging concern named vaccine hesitancy (VH). The Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE Group) has given the following definition of VH: “Vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific varying across time, place and vaccines. It includes factors such as complacency, convenience and confidence”.4 Vaccine hesitant people can be represented by people who refuse or delay vaccination, but also by those who accept them with uncertainty regarding their safety or efficacy.5 VH may not concern all vaccines,6 and includes various determinants that are sometimes linked. These factors can be divided in two main categories: socio-demographic factors (age, gender, level of education, type of work, beliefs, culture, traditions) and non-socio-demographic factors (access to hospitals, financial and non-financial barriers such as lack of time, workload). The latter can be clustered together in the 5A taxonomy which includes access, affordability, awareness, acceptance and activation.7 Doubts about vaccine effectiveness and fear of side effects are the main reasons that explain VH; people express doubts, due to a context of “individual's rights” and a requirement for high quality of drugs.8 According to an international study that measured confidence in vaccination among the general public in 67 countries, France was the country in which people were most doubtful about vaccine safety.9 Worries about vaccine safety and fear of side-effects, along with the perception of a low importance of a given vaccine, are among the frequent reasons explaining a low immunization rate among children.10 In addition, some physicians and parents (known as vaccine hesitant parents, VHPs) consider children as already receiving too many vaccines.11 Importance of vaccination is more often reported in the elderly, who are generally more favorable to vaccination as they personally experienced serious diseases as children, and are thus aware of the impact that vaccination can have on the prevention of these diseases.12

VH can lead to difficulties in eradicating life-threatening infectious diseases, resulting in an increase of case fatality rates and critical complications that are associated with outbreaks and a growth in healthcare expenditures.13 Addressing it is therefore important to continuously improve health-related quality of life of the general population.

The present review aims to summarize all the actions and strategies that have been implemented to address VH issue in France, and more broadly, to enhance vaccine acceptance.

Background

Vaccination coverage rates (VCR) are not satisfactory in France. One of the factors explaining this situation is VH.14 Mistrust and questions about vaccination can be attributed to many factors. First, vaccination is a victim of its success; the fact that many vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs) have been eradicated since the introduction of vaccines has led to the perception of vaccination as unimportant. However, the maintenance of VCR remains necessary to tackle infections due to the propagation of germs coming from regions were they are still circulating.15 The internet also plays an important role in fueling vaccine controversies, and generating hesitant behaviors towards vaccination.16 Online tools allow vaccine-related rumors to spread rapidly all over the world,17 but the information is sometimes published without scientific validation.18 Moreover, before vaccination, people often search for information on the internet,19 and sometimes seek for information in accordance with their beliefs.20 Yet, positive messages regarding vaccination are not often shared in the media, but people can be more tempted to share doubts if they have experienced adverse effects that they attributed to vaccines.21 Vaccine-related controversies have emerged in France since the beginning of the 1990s, and started with controversies regarding the presence of adjuvants in vaccines, and the supposed link to macrophagic myofasciitis.22 The same period saw the onset of controversies related to the hepatitis B vaccine (HBV), which was alleged to be associated with multiple sclerosis. Concerns focused on adjuvants (thimerosal and aluminum hydroxides) contained in the vaccine.23 However, several years later, safety data are reassuring and show a favorable benefit/risk ratio for HBV.24 Controversies also affected the meningococcal C vaccine (Men C), due to quality issues observed in some syringes. However, after assessment, the French Medicines Agency later confirmed that there was no health risk due to this for the children who received the vaccine.25 The human papillomavirus vaccine has also been the subject of controversies, because of the alleged association with auto-immune diseases, but a study recently concluded that such a link does not exist.26 The influenza vaccination campaign management during the H1N1 pandemic of 2009–2010 has also affected confidence in vaccination, as it resulted in a reduction in vaccination rates for seasonal influenza vaccination.8,27 During the pandemic, the majority of the population doubted the safety of the vaccine owing to its rapid marketing and consequent poor evaluation of adverse effects.6 Since then, vaccination rates against seasonal influenza dramatically dropped in WHO member European countries.28 This context of hesitancy is associated with the resurgence of epidemics, as it has recently been the case for measles.29 Another main obstacle to vaccination is the coexistence of mandatory and recommended vaccines in the immunization schedule; recommended vaccines can be in fact considered less important .30 Moreover, the vaccination process is sometimes acknowledged as complex, as many steps are required before vaccination,31 and repetitive vaccine shortages currently observed are responsible for mistrust in pharmaceutical firms and health authorities.32

This context urged health authorities and medical staffs in some care centers to implement approaches with the aim of resolving the issue of VH.

Search strategy

To identify relevant articles from the literature, a search was performed by the author, in May 2017, and using the following electronic databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of science, International pharmaceutical abstracts, Pascal and Francis, Banque de données en santé publique (BDSP), ScienceDirect, and Embase. As the beginning of the controversies about vaccines in France started in the 1990s,22 the databases were searched for English and French articles published from 1990 up to May 2017. The search was performed using keywords combined with the Boolean search operators. The vocabulary thesaurus of the databases were also used if available (Mesh in PubMed, Emtree in Embase, thesaurus of the BDSP). Selection criteria for articles was: focusing on any mean to promote vaccination in mainland France, including educational programs and immunization programs. Key words used are presented in.Table 1. Additional research through the Google search engine was also performed with the phrase “hésitation vaccinale France”.

Table 1.

Key words used for the research.

| In English | In French | Key words used in the vocabulary thesaurus of databases |

|---|---|---|

| “immunization campaign” OR “vaccination program” OR “vaccination campaign” OR “vaccination awareness” OR “vaccination promotion” OR “vaccination uptake” OR “vaccine hesitant” OR “vaccine hesitancy” OR “immunization program” OR “advertising campaign” OR “education” OR “knowledge” OR “attitude” OR “behavior” OR “behaviour” OR “beliefs” AND (frenc* OR french* OR France) | (“campagne de vaccination” OU “programme vaccination” OU “hésitation vaccinale”) ET Franc* | In PubMed: “Immunization Programs”[Mesh]) AND “France”[Mesh]; In Embase: “public health campaign” AND “vaccination” AND “France”; In the BDSP: ([campagne information] OU [programme élargi vaccination]) ET [France]) |

Review results

Overview of study characteristics

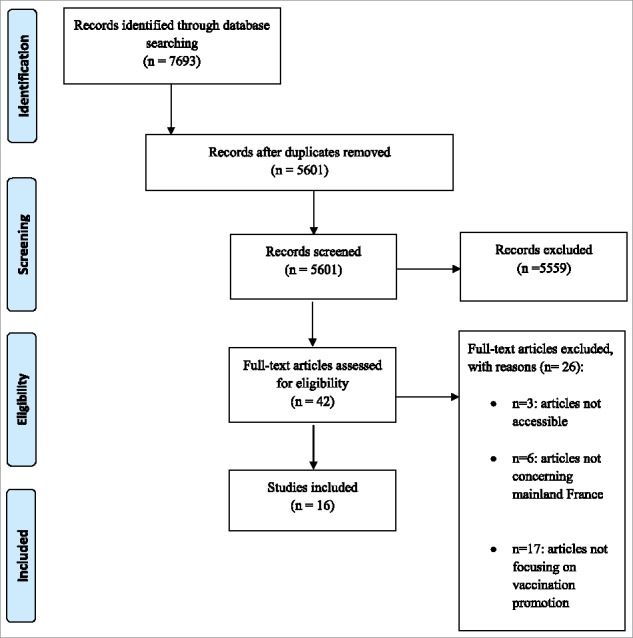

Of 7693 articles screened, 16 articles qualified for inclusion. The search performed through Google allowed for the inclusion of six guidelines published by national health authorities and medical associations. The process for inclusion and exclusion of articles is shown on the flow diagram reported in Figure 1. Different means have been used to promote vaccination (Table 2). Most have consisted in the deployment of vaccination campaigns. Guidelines regarding main recommendations published by national health authorities and medical associations are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Flow chart diagram of study inclusion and exclusion.

Table 2.

Summary of published articles on strategies to address vaccine hesitancy in France.

| Description of articles |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author/ title/year of publication | Location | Period | General setting | Outcomes | Main conclusions |

| Location Period General setting | |||||

| Jean Beytout, Enseignements de la campagne de vaccination anti-méningococcique dans le Puy-de-Dôme [Lessons from the anti-meningococcal immunization campaignin the Puy-de-Dôme], 200233 | Clermont-Ferrand | January 2002 | Purpose: vaccinate 70000 persons in the agglomeration and the neighboring municipalities; Targeted population: young under 21, adults more than 25, in close contact with the at-risk population | Concerns from parents, because of the adverse effects registered during Phase III trial of the vaccine in Great Britain; Occurrence of side effects (flu symptoms, gastro-enteritis), which caused a delay in the administration of the first dose in some cases | Successful campaign with a great mobilization of HCPs, teaching and administrative staff; More than 80% of the targeted vaccinated |

| D. Lévy-Bruhl, Vaccination campaign following an increasein incidence of serogroup C meningococcaldisease in the department of Puy-de-Dôme69 | Department of Puy-De-Dôme | From January, 16th 2002 to March 9th, 2002 | Purpose: vaccinate 100000 people; Targeted population: young adults, from 2 months-20 years old, studying in a limited area of the department, geographically defined as including all reported cases of invasive Men C disease since March 2001; Use of the Men C conjugate vaccine; Vaccination recommended for young people aged 2–24, living in boarding schools, communities, or working with children; New arrivals in the county for a period of more than 1month were also targeted; 1390 adverse effects identified (mostly migraines and dizziness: 1.73% of all vaccinated) | 80000 persons vaccinated | Successful campaign (80% of the target population were vaccinated) |

| D. Lévy-Bruhl, Campagne de vaccinationcontre le méningogoque C dans le Sud-Ouest, un premier bilan [Vaccination campaign against meningococcal C in the South-West, an initial assessment], 200334 | South-West region, 3 departments | October 21 to December 21, 2002 | Purpose: vaccinate 315000 persons; Targeted population: children from 2 months-20 years old, some people aged 20–24, particularly those living in children's communities | Four cases of MD diagnosed: one person was not vaccinated, 2 persons received the vaccine 3 days before (the vaccine needs much more time to be effective), 2 persons were aged 25 and 29 years old, and were not among the population targeted by the campaign; Local and immediate adverse reactions were mostly not worse, with a favorable evolution35 | Successful campaign,good deployment; No case of MD observed in the 0–18years old; 70% of the target population were vaccinated |

| S. Laurence, Measles vaccination campaign among vulnerable populationsduring the peak of the 2011 epidemic in Marseille, 201236 | Marseille | May to September 2011 | Targeted population: The Roma population, non-vaccinated or with unknown vaccination status (n = 720) | 326/720 people reached by the first injection (45.28%); Campaign prematurely interrupted, because the population was evicted from its places of life, and the follow-up couldn't be efficient | The campaign didn't have a great success; Only 37 persons received the second dose of the vaccine, as Roma people were evicted from their location |

| J. Belmin, Educational vaccine tools: the French initiative, 200943J. Belmin, Vaccination in older adults: development of an educational tool, Vaxisenior, in France, 201464 | 2000, update in 2008 | Targeted population: geriatricians, physicians who teach geriatrics, internal medicine or infectious diseases; Tool organized in 8 sections including general information, immunity and oldness, and some specific vaccines (DTP, influenza, pertussis, pneumococcus, herpes zoster, and vaccines for travelers); Organized in slides collected into a CD; Content: Information about VPDs, consequences, benefits and adverse effects of vaccination; national immunization programs and recommendations also included; First set up in 200043, update in 2008 with the recommendation schedule for immunization64 | |||

| S. Krypciak,Improvement of pneumococcal immunization coverage in older patients, 201470 | Department of Val de Marne | November 2009 to August 2010 | Targeted population: elderly aged more than 75, in short geriatric stay, mainly affected by cardiac insufficiency (75.5% of cases); 2 actions used: sensitization of the attending physician and proposal of vaccination during the hospital stay | The sensitization of the attending physician improved VCR from 15.9 to 18.2%; A systemic proposal of vaccination during the hospital stay improved VCR from 6.1 to 84.5% | Both actions improved VCR |

| A Chamoux, Impact study of an active antiflu vaccination program on the Clermont-Ferrand teaching hospital staff, 200641 | Clermont-Ferrand university Hospital | October 14 to October 20, 2003 | Targeted population: hospital staff; Letters sent to participants to make them aware of the campaign; Medical information meetings planned to discuss about the way of transmission of influenza, vaccination and its benefits, the risk for the most fragile patients, and also for HCPs and their surroundings | VCR multiplied by 2.6, in comparison with the previous year: (4.8→12.6%) Post-vaccination, reactions observed in one third of cases (1/3) | Successful campaign, increase of the VCR |

| F Baudier, Pilot campaign to promote vaccination:description and preliminary results of a regional French program, 200771 | Franche-Comté region | Launch in 2003, consisted in a one-week immunization campaign every year during 3 years | Targeted population: the general population; Lot of activities proposed: trainings, writing materials (posters, brochures); exhibitions, media campaign; Actions mphasized on schools and pharmacies in the second year | The reimbursement data showed, 2 months after the week-immunization, an increase in VCR of 5% for 2004, and more than 10% in 2005 | The results after two years were satisfactory; An increase of vaccination-related discussion between physicians and their patients was observed |

| A. Decréquy, Cocooning strategy: Effectiveness of a pertussis vaccination program for parents in the maternity unit of a university hospital, 201639 | Caen university hospital | 2012 | Vaccination of parents: vaccination of fathers during the pregnancy, and vaccination of mothers after the birth, before the discharge from the hospital, or prescription given to them to practice vaccination in town | VCR multiplied by 4 | Successful campaign; lack of time was the main reason for non-vaccination |

| S. Laurence, Campagne de vaccination rougeole des populations précaires, retour d'expérience[Measles vaccination campaign for precarious populations, feedback], 201337 | Department of Seine-Saint-Denis | January to June 2012 | Purpose: increase VCR against measles in precarious population (The Roma population); 22 shantytown targeted | 250/720 persons vaccinated(34.7%); Only 5% received the second dose | Low success; Reasons for low success: two shantytowns previously targeted by a similar campaign, expulsions, other health concerns in the shantytown (scabies epidemy), refusal |

| A Bone, Population and risk group uptake of H1N1 influenza vaccine in mainland France 2009–2010: Results of a national vaccination campaign, 201038 | The whole France | End of 2009 to the beginning of 2010 | Purpose: lower the burden of H1N1 disease in France; Targeted population: the whole French population; Vaccination made by mobile medical teams and vaccination centers | High vaccine uptake among children (20.7%), with a decrease in adults aged 18–24 (3.1% vaccinated) | Low overall vaccine uptake; VCR lower than those observed with the seasonal influenza vaccine for people aged 65 or over (3.9% vaccinated) |

| B Leboucher, Impact of postpartum information about pertussis booster to parents in a university maternity hospital, 201240 | Angers university hospital | Two periods: Period A: January 1st toMarch 31st, 2008; Period B: January 19th to April 19th, 2009 | Use of a protocol that combined information about the booster dose, and a prescription of pertussis vaccine, prior discharge from the hospital; Deployment of a telephone survey during two periods of 3 months (corresponding to periods A and B), 2 months after the delivery | VCR in period A: 67,9% (mothers), 63.1% (fathers); VCR in period B: 68.9% (mothers), 62.4% (fathers); The vaccination was mainly done in the first month after the delivery | The majority of mothers reported that the documents delivered to them helped them understand the benefits and importance of vaccination; Reasons for non-vaccination were lack of time, vaccination already received less than 2 years before, forgetting, breastfeeding |

| M Rothan-Tondeur,Randomised active programs on healthcare workers’ flu vaccination in geriatrics healthcare settings in France: the VESTA study, 201072 | Geriatrics healthcare settings, long term care and rehabilitation care, throughout the whole France | 2 programs both conducted in flu seasons; Program 1: 2005–2006 flu seasons; Program 2: 2006–2007 flu season; | Purpose: identify obstacles to influenza vaccination for HCPs, and develop specific actions to counteract this; Targeted population: HCPs; Program 1 aimed to give information to the HCPs, and remove fears and doubts; it was organized in 52 slides and 4 short movies; Program 2 was incentive, with a reward in case of an increase of vaccination coverage | Program 1 failed to increase VCR; In program 2, VCR increased by 44% in the interventional group, compared to the control group (27%), only in non-previously vaccinated subgroup | The program 1 didn't show any significant difference in term of VCR during the 2005– 2006 influenza season: it was inefficient; Non-vaccinated nursing auxiliaries and non-vaccinated nurses were mainly receptive to the program |

| B Dunais, Influenza vaccination: impact of an intervention campaign targeting hospital staff, 200642 | Nice university hospital | October 16th to December 5th, 2002 | Active intervention led by a mobile medical team, to raise awareness about the importance to be vaccinated against flu, combined to an on-site vaccination; Targeted population: HCPs working in Nice University Hospital: staff of 6 departments responsible for the care of patients with higher risk of getting influenza during an epidemic period, or patients at risk of complications related to influenza; Information sessions with all the staff in close contact with patients: consisted in slideshow that explain the matters related to the disease, responses to doubts and questions regarding the vaccination | 35% of the total targeted staff decided to receive the vaccination | Main reason to explain low coverage rates was lack of time; Reasons for non-adherence to the program: fear of side effects, doubts about vaccination safety, polemics concerning HBV in France |

| O Launay, Impact of free on-site vaccine and/or healthcare workers training on hepatitis B vaccination acceptability in high-risk subjects: a pre-post cluster randomized study, 2014(Launay et al., 2014) | Anonymous HIV and HBV testing centers | September 2009 to March 2011 | Purpose: assess the impact of free on-site hepatitis B vaccine availability and/or HCPs training, on vaccination acceptability in high risk groups, with 3 different interventions (training of HCPs, availability of a free hepatitis B vaccine, or both interventions); Vaccination offered on the spot | Increase of vaccine acceptability and vaccine coverage, mainly in the group that received both interventions; No significant change in the group for which the solely intervention was the training of HCPs | Both interventions combined were more effective; Training of HCPs as a single strategy was not effective |

Table 3.

Summary of main recommendations from health authorities and medical associations on strategies to address vaccine hesitancy in France.

| Title/Author/year | Main recommendations |

|---|---|

| La vaccination : un acte individuel pour un bénéfice collectif [Vaccination: an individual act for a collective benefit], Academy of pharmacy, 201247 |

For HCPs: reinforce initial and continuous vaccination trainings empowerment of pharmacists to practice vaccination use of electronic booklets use of a single term to describe mandatory vaccines and recommended vaccines |

| Programme national d'amélioration de la politique vaccinale 2012–2017 [National Program for Improving Immunization Policy 2012-2017], National direction of health, 201251 | Simplify the vaccination schedule Improve access to vaccination Redefine the terms of “mandatory vaccines” and “recommended vaccines” |

| Avis relatif à la politique vaccinale et à l'obligation vaccinale en population Générale (hors milieu professionnel et règlement sanitaire international) et à la levée des obstacles financiers à la vaccination [Opinion on immunization policy and mandatory vaccination in the general population (outside the professional environment and international health regulations) and to the removal of financial obstacles to vaccination], High Council of Public Health, March 13th, 2013 and March, 6th, 201415 |

Organization of a debate about the lift of mandatory vaccines, within the frame of health authorities Extend vaccinations places to life communities Full coverage of the fees engaged into the vaccination act Empowerment for other HCPs to practice vaccination |

| Rapport sur la politique de vaccination [Report on Immunization policy], S. Hurel, 201650 | Set up of a website dedicated to vaccination, with a Questions & Answers section Monitor the content of social media Publication of a periodic electronic bulletin of information for HCPs, on the latest developments concerning vaccines and immunization policies, with limitless access Use of new technologies that combined an increase in life duration of vaccines and shortens the time needed to expand production, to avoid vaccine shortages Facilitate the deployment of information tools for HCPs |

| Rapport sur la vaccination [Report on immunization], Citizens' consultation committee on immunization, 201631 |

Implementation of a website to inform HCPs and the public on immunization matters Full coverage of the purchasing costs of vaccines through compulsory health insurance schemes Temporary extension of the child's immunization obligations with the possibility of invoking an exemption clause Development of research programs covering different aspects of immunization Facilitate vaccination in all prevention, care or shelter settings, by putting the vaccines available for physicians, pediatricians, specialists, by enabling nurses to make revaccinations, by giving a financial support to centers and nursing homes Empowerment of pharmacists in vaccination, after adequate training, to promote access to vaccination, in collaboration with physicians |

| Avis relatif à la vaccination anti- Méningococcique C [Opinion on the vaccination against Meningococcal C], High Council on Public Health, 2016.68 |

Recommendation of Men C vaccination for children under 1, with one dose at 5 months followed by a booster dose at 12 months |

Vaccination campaigns against Men C

Many campaigns targeting serogroup C of Neisseria meningitis were implemented, owing to the high number of Men C cases in the Auvergne and South-Western administrative regions of France. The target population was mainly constituted of young adults and persons in close contact with the at-risk population. Various means were used to conduct the campaigns. In the Clermont-Ferrand city administrative area (located in the Auvergne region), vaccination was performed by school and university medical teams, reinforced by other physicians. Information was given to the public via the local and national press. On February 7, 2002, more than 80% of the target population were vaccinated.33 The Men C campaign conducted in the South-West region was also successful; no case of meningococcal disease (MD) occurred in the 0–18 years old,34 and the vaccine was broadly well tolerated.35

Vaccination campaigns targeting precarious populations

Precarious populations were part of immunization strategies, in different regions of the country. Due to the 2008 to late 2011 Measles Mumps Rubella (MMR) outbreak in Europe, the humanitarian organization Medecins du monde led a vaccination campaign targeting the Roma population living in shantytowns, in many areas.36,37 Roma people were targeted because they mostly come from Bulgaria and Romania where as in France, the number of cases of measles was elevated. Nevertheless, the instability of this population, their eviction, and other health concerns that occurred during the immunization period made it difficult to reach adequate VCR.

National immunization campaign against H1N1 pandemic

Negative outcomes were reported for the national influenza immunization campaign during the occurrence of the H1N1 influenza pandemic as low immunization rates were observed.38 Vaccination performed by mobile teams failed to strengthen vaccine uptake. Moderate success was reported in infants, but poor success was reported in adults and elderly.

Immunization programs targeting children

Specific actions also targeted children, with the implementation of the “cocooning” strategy to prevent young infants from getting pertussis. This approach resulted in the increase of VCR in both mothers and fathers of newborn infants.39,40

Vaccination campaigns for medical staff

Vaccination campaigns targeting medical staffs increased VCR, in the cities of Clermont-Ferrand and Nice. Organization of meetings with the medical staff, prior the start of the campaigns, to deliver scientific messages on the importance of vaccination and remove doubts by answering to queries, resulted in improvement of vaccine uptake, and contributed to develop a positive attitude towards vaccination.41,42

Tools to promote vaccination for the elderly

A tool called Vaxisenior and designed for use by physicians was created to promote vaccination in the elderly. It consisted of slides collected into a CD. Slides contained generalities on immunization, importance of vaccination, and the national immunization schedule. The tool was made for physicians.43,64

Discussion

Vaccination programs launched in France so far show encouraging results, but VH remains a complex issue that is difficult to tackle, as no effective strategy has shown striking evidence to address it65 multiple strategies are however acknowledged by some authors as having potential impact to counter VH.22

No previous study reviewing all the methods launched in France to address VH has been published to date. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first review focusing on that point. Vaccination campaigns were the means most used to promote vaccination, but complementary actions, such as developing educational tools to promote immunization, meetings with the delivery of scientific messages and exchanges to facilitate vaccination were also implemented. To improve the overall VCR, specific actions towards general practitioners (GPs) can be implemented, as they have a close contact with patients regarding health matters; Physicians are seen as models for their patients, through their own health behaviors.45 Vaccination acceptance of healthcare providers (HCPs) can be improved if they are well informed about the benefits and importance of vaccination, not only for them, but also for patients they are in charge of. In that regard, initial training and continuing education appear important.18 As some physicians may have questions related to the immunization process, a platform on which they can rely on in such cases can be proposed. This is already the case in Switzerland, with the academic network INFOVAC.46 Furthermore, to simplify the immunization process, HCPs other than physicians can be empowered for vaccination.47,31 The Social Security Financing Act published on December 24, 2016, referred to the possibility for pharmacists, on a three-year experimental basis, to administer the seasonal influenza vaccine to adults. This experimentation started in two regions in early October 2017. The first results are satisfactory.48

Facilitating access to vaccination is also a key element,46 with the extension, for instance, of vaccination at more convenient business hours (weekends and evenings). Vaccination can also be considered in “non-traditional” settings such as nursing homes, home visits, childcare centers,49 and can be carried out in environments such as schools, university preventive medicine settings, or occupational settings for workers. Two vaccination campaigns have targeted the Roma population living in France. Nevertheless, improvement of VCR was not observed but this strategy underlines the need to target precarious populations who are often far from the prevention mechanisms.37

Availability of vaccines is necessary to ensure a rapid access to vaccination services and facilitate public adherence to vaccination50; but there are recurrent vaccine shortages. The reasons for these shortages vary,32 and need appropriate communication campaigns. Establishing stocks of some important vaccines may help address supply pressures.50 To increase availability of new vaccines the research and the industrial production of vaccines must be enhanced.31,51

Underscoring the importance of vaccination for the elderly to their relatives and caregivers is a way to optimize vaccination rates in this population.44 French health authorities can rely on recommendations published by the European geriatric societies to improve VCR rates in this subgroup. Regarding pediatric immunization, fear of pain is known to be one of the main barriers to vaccination most often reported52; thus, injection pain should be appropriately managed.1 To this end, pre-administration of topical anesthetics, distraction, or the feeling of protection expressed by parents can be helpful.22 For parents with high workload who could more often forget to update the immunization status of their children, the use of postal and telephone reminders appears to be the most effective means to enhance pediatric vaccine uptake.53 The use of SMS reminders can also be part of the strategies employed.54

To simplify access to vaccine-related information, a toll-free phone number, established to provide vaccine-hesitant persons with any information they may require prior to vaccination can be useful.

This is already the case for many other health matters such as infectious disease caused by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), hepatitis, asthma, allergies, and drug addiction.

Considering that trust in institutions is significantly associated with low VH, it is important to implement actions in order to restore the confidence in health policies. To avoid the feeling that governments are influenced by the pharmaceutical industry, transparency regarding the conflicts of interests of those involved in vaccination policy should be clearly provided to the public.31,18 The “Bertrand Law” published in May 2013 requires pharmaceutical companies to disclose all relationships that they might have with all stakeholders engaged in health matters, including vaccination. Measure such as this, which is already effective, can help build and sustain general confidence. Some guides are available to help governments reestablish confidence in health institutions among HCPs. The guide from the European centre for disease prevention and control,17 the “Communicate to vaccinate” guide,55 and the Tailoring Immunization Programs guide56 have been published for this purpose. The latter underlines the importance of segmenting the population to define subgroups at risk of developing VH. In this way, different groups can be constituted (adolescents, parents, the elderly, at-risk patients with chronic diseases, people living with toddlers) to set up suitable action plans.49

As mandatory vaccines are sometimes perceived as a restriction of individual liberty, suggestions have been made to transfer the current mandatory vaccines to the list of recommended vaccines.18 It should be noted, however, that such an action with tuberculosis vaccine has resulted in a decrease of VCR in the new targets of the vaccine.57 The possibility of such a reaction should be thoroughly evaluated. The issue is emphasized by the existence of vaccines that combine mandatory and recommended ones: they were most used to respect mandatory schedules for infants, especially for diphtheria tetanus and poliomyelitis (DTP) vaccine which was the unique mandatory immunization in France until January 2018. A solution to this issue was brought by the French ministry of health, which decided to extend immunization obligation to 11 vaccines, including the DTP vaccine, for infants born as of January 1st, 2018. The 11 vaccines should be administered during the first 18 months of life.67

A new immunization schedule for toddlers with fewer doses of vaccines began to be implemented in France in April 2013 for diphtheria, tetanus, poliomyelitis, pertussis and invasive infections due to Hib.66 This schedule consists of 2 primary doses of vaccine followed by a booster dose (2+1 schedule), replacing the 3+1 schedule. However, it is difficult to confirm whether this simplified schedule has affected VCR for infants as VCR have increased only for some vaccines.58 The impact of new mandatory immunization schedule for infants on VCR is now to be assessed.

As specified by the WHO, convenience is one of the determinants of vaccine hesitancy.4 Its refers to many factors that may have an effect on vaccine uptake, and includes “ability to understand (language and health literacy)”.12 Health literacy is defined as the “specific capacity to retrieve, understand, apply and use medical information, interacting with the health system”.59

Those with insufficient health literacy can have less healthy behaviors, as they have difficulties in understanding and using health information provided to them to make appropriate health decisions.60 Evaluation of health literacy has already been done in France for diabetes.61,62 Nevertheless, the more specific evaluation of vaccine literacy should be conducted and its results taken into account to implement adequate interventions aiming to strengthen vaccination advocacy. Improving vaccine literacy skills can have a positive impact on immunization rates.

Because people increasingly rely on social media, online tools can be used to promote vaccination.21 However, in such case, the content needs to be well monitored,49 and the language used should be clear1;the delivery of scientific information to the public is an indispensable way to reduce the impact of vaccine controversies.63

This review aimed to be exhaustive, as it has included multiple strategies implemented in different areas of France to fight against VH and thus enhance vaccine uptake. Although it clearly demonstrates the use of various means to address VH, leading to great results for most studies, some limitations are to be considered. First, only vaccination programs conducted in mainland France were included, due to the application of the principle that action plans launched in French overseas departments and territories are likely to be the same, as the same national health policies apply. However, this bias, even if of minor importance, could have generated missing data. Additionally, three articles on the BDSP were not be accessible, as the link was non-functional. However, as a relative high number of articles and guidelines were included in the review, it can be considered that they represent well the methods launched to address vaccine hesitancy issue in mainland France.

Second, most of the strategies concerned only specific subgroups of the population (e.g., HCPs working in hospitals, patients attending infectious diseases centers). As these patients represent a minority of the population, such findings may not accurately reflect the impact of these strategies on the general population.

Lack of access may have a negative impact on vaccination uptake with the potential to increase VH. For this reason, strategies launched to enhance vaccine uptake were included in the review, because such approaches can indirectly contribute to reduce VH among the population. These data could help health authorities in considering more immunization programs focusing on enhancing global vaccine uptake to effectively address VH.

However, Addressing VH issue requires interventions and actions implemented on a regular basis, and needs collaboration between the main actors of the immunization process, including health authorities, HCPs and patients. Qualitative studies may be of great help in understanding determinants of vaccine uptake at the individual level, as this can lead to creating tailored interventions for at-risk groups.

Conclusion

Several actions have been implemented to address the issue of VH in France. Supplying vaccine-hesitant people with appropriate information seems insufficient to overcome their hesitancy; further studies are therefore needed to identify the most effective strategies to address VH. Moreover, action plans previously launched should be part of a long-term approach.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Philip Robinson (DRCI, Hospices Civils de Lyon) for help in manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.MacDonald N. E., Smith J., Appleton M. Risk perception, risk management and safety assessment: what can governments do to increase public confidence in their vaccine system? Biologicals: Journal of the International Association of Biological Standardization. 2012;40(5):384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goulenok T. Vaccination anti-pneumococcique chez l'adulte : comment améliorer la couverture vaccinale ? Journal Des Anti-Infectieux. 2014;16(2):89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.antinf.2014.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Guide to tailoring immunization programmes. 2017, March 18 Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/2013/guide-to-tailoring-immunization-programmes

- 4.WHO | Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy 2016, June 7 Retrieved March 29, 2017, from http://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/vaccine_hesitancy/en/

- 5.Peretti-Watel P., Verger P. L'hésitation vaccinale : une revue critique. J. Des Anti-Infectieux. 2015;17(3):120–4. doi: 10.1016/j.antinf.2015.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward J. K. Rethinking the antivaccine movement concept: A case study of public criticism of the swine flu vaccine's safety in France. Soc. Sci. Med. (1982). 2016;159:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson A., Robinson K., Vallée-Tourangeau G. The 5As: A practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2016;34(8):1018–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loulergue P., Floret D., Launay O. Strategies for decision-making on vaccine use: the French experience. Ex. Rev Vaccine. 2015;14(7):917–22. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.1035650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larson H. J., Figueiredo A., de Xiahong Z., Schulz W. S., Verger P., Johnston I. G., Cook AR, Jones NS. The State of Vaccine Confidence 2016: Global Insights Through a 67-Country Survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ECDC Conducting health communication activities on MMR vaccination. 2010. Retrieved from https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/1008_TED_conducting_health_communication_activities_on_MMR_vaccination.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams S. E. What are the factors that contribute to parental vaccine-hesitancy and what can we do about it? Human Vaccine. Immunother. 2014;10(9), 2584–96. doi: 10.4161/hv.28596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SAGE group Report of the SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. 12 November 2014 2014, November 12. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szucs, T., Quilici, S., Panfilo, M. From population to public institutions: what needs to be changed to benefit from the full value of vaccination. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2015;3(1):26965. doi: 10.3402/jmahp.v3.269657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lévy-Bruhl D. Hésitation vaccinale: données françaises. 2016, July 6. Retrieved from http://www.rencontressantepubliquefrance.fr/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/LEVY_BRUHL.pdf

- 15.HCSP Politique vaccinale et obligation vaccinale en population générale. Paris: Haut Conseil de la Santé Publique; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.hcsp.fr/explore.cgi/avisrapportsdomaine?clefr = 455 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward J. K., Peretti-Watel P., Larson H. J., Raude J., Verger P. Vaccine-criticism on the internet: New insights based on French-speaking websites. Vaccine. 2015;33(8):1063–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ECDC Communication on immunization-building trust. 2012;2012 Retrieved from https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/TER-Immunisation-and-trust.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaudelus J., Pontual L. Vaccins refusés ou discutés par les parents. Que faire ? Médecine Thérapeutique/Pédiatrie. 2015;18(3):119–25. doi: 10.1684/mtp.2015.0568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moyroud L., Hustache S., Goirand L., Hauzanneau M., Epaulard O. Negative perceptions of hepatitis B vaccination among attendees of an urban free testing center for sexually transmitted infections in France. Human Vaccine. Immunother.. 2016;0(0):1–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1264549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kestenbaum L. A., Feemster K. A. Identifying and addressing vaccine hesitancy. Pediatric Annals. 2015;44(4):e71–75. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20150410-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stahl J.-P., Cohen R., Denis F., Gaudelus J., Martinot A., Lery T., Lepetit H. The impact of the web and social networks on vaccination. New challenges and opportunities offered to fight against vaccine hesitancy. Medecine ET Maladies Infectieuses. 2016;46(3):117–22. 10.1016/j.medmal.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verger P., Collange F., Fressard L., Bocquier A., Gautier A., Pulcini C., Peretti-Watel P. Prevalence and correlates of vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners: a cross-sectional telephone survey in France, April to July 2014. Eurosurveillance. 2016;21(47). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.47.30406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balinska M. A. Hepatitis B vaccination and French Society ten years after the suspension of the vaccination campaign: how should we raise infant immunization coverage rates? Journal of Clinical Virology: The Official Publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2009;46(3):202–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boazis M. Vaccin contre l'hépatite B et sclérose en plaques : bilan des dernières études épidémiologiques. J Pharm Clin. 2003;21(4):228–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sécurité du vaccin contre la méningite C Meningite… – MesVaccins.net 2016, July 9 Retrieved March 30, 2017, from https://www.mesvaccins.net/web/news/9262-securite-du-vaccin-contre-la-meningite-c-meningitec-c-etait-une-fausse-alerte

- 26.Grimaldi-Bensouda L., Guillemot D., Godeau B., Bénichou J., Lebrun-Frenay C., Papeix C., Labauge P, Berquin P, Penfornis A, Benhamou PY, PGRx-AID Study Group, et al. . Autoimmune disorders and quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination of young female subjects. J Intern Med. 2014;275(4):398–408. doi: 10.1111/joim.12155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peretti-Watel P., Verger P., Raude J., Constant A., Gautier A., Jestin C., Beck F. Dramatic change in public attitudes towards vaccination during the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in France. Eurosurveillance. 2013;18(44):20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raude J., Fressard L., Gautier A., Pulcini C., Peretti-Watel P., Verger P. Opening the “Vaccine Hesitancy” black box: how trust in institutions affects French GPs’ vaccination practices. Ex. Rev. Vaccine. 2016;15(7):937–48. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2016.1184092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rougeole : 4 fois plus de cas qu'au premier quadrimestre 2016 Vers une vaccination ROR obligatoire ? 2017, June 22. Retrieved June 22, 2017, from https://www.vidal.fr/actualites/21595/rougeole_4_fois_plus_de_cas_qu_au_premier_quadrimestre_2016_vers_une_vaccination_ror_obligatoire/

- 30.Les Français et la Vaccination : pourquoi tant d'h… – MesVaccins.net 2016, October 4. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from https://www.mesvaccins.net/web/news/9598-les-francais-et-la-vaccination-pourquoi-tant-d-hesitation

- 31.Comité d'orientation de la concertation citoyenne sur la vacination Rapport sur la vaccination. 2016, November 30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medqual La lettre d'actualités N° 170. 2017, Février [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beytout, J., Laurichesse, H Enseignements de la campagne de vaccination anti-méningococcique dans le Puy-de-Dôme. Med ET Mal Infect. 2002(6):259–60. doi: 10.1016/s0399-077x(02)00368-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruhl D. L. Campagne de vaccination contre le méningocoque C dans le Sud-Ouest: un premier bilan. Journal de Pédiatrie et de Puériculture. 2003;16(4):224–226. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bagheri H., Gony M., Montastruc J.-L. A propos d'une campagne de vaccination contre la méningite C dans les Hautes-Pyrénées : réflexions de pharmacovigilance. Thérapie. 2005;60(3):287–94. doi: 10.2515/therapie:2005038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurence S., Chappuis M., Rodier P., Labaume C., Corty J.-F. Campagne de vaccination hors centre contre la rougeole des populations précaires en période de pic épidémique, Marseille 2011. Revue d’Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique. 2013;61(3):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2012.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laurence Sophie, Chappuis M., Lucas D., Duteurtre M., Corty J.-F. Campagne de vaccination rougeole des populations précaires : retour d'expérience, Ambulatory Measles Immunization for deprived populations: lessons learned. Santé Publique. 2013;25(5), 553–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bone A., Guthmann J.-P., Nicolau J., Lévy-Bruhl D. Population and risk group uptake of H1N1 influenza vaccine in mainland France 2009–2010: results of a national vaccination campaign. Vaccine. 2010;28(51):8157–61. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Decréquy A., de Vienne C., Bellot A., Guillois B., Dreyfus M., Brouard J. Stratégie du cocooning : efficacité d'une politique de promotion de la vaccination anticoquelucheuse des parents à la maternité d'un CHU. Arch Pediatr. 2016;23(8):787–91. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leboucher B., Sentilhes L., Abbou F., Henry E., Grimprel E., Descamps P. Impact of postpartum information about pertussis booster to parents in a university maternity hospital. Vaccine. 2012;30(37):5472–81. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chamoux A., Denis-Porret M., Rouffiac K., Baud O., Millot-Theis B., Souweine B. Étude d'impact d'une campagne active de vaccination antigrippale du personnel hospitalier du CHU de Clermont-Ferrand. Med ET Mal Infect. 2006;36(3):144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunais B., Saccomano C., Mousnier A., Roure M.-C., Dellamonica P., Roger P.-M. Influenza vaccination: impact of an intervention campaign targeting hospital staff. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27(5):529–31. doi: 10.1086/504453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belmin Joel, Bourée P., Camus D., Guiso N., Jeandel C., Trivalle C., Veyssier P. Educational vaccine tools: the French initiative. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21(3):250–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03324906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belmin J. Improving the vaccination coverage of geriatric populations. J Comp Pathol. 2010;142 Suppl 1:S125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2009.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collange F., Verger P., Launay O., Pulcini C. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors of general practitioners/family physicians toward their own vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(5):1282–92. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1138024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegrist C., Desgrandchamps D., Heininger U., Vaudaux B. How to improve communication on vaccine issues at the national level? INFOVAC-PED: an example from Switzerland. Vaccine. 2001;20 (Suppl 1):S98–S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Académie nationale de pharmacie. La vaccination: un acte individuel pour un bénéfice collectif. 2012, October 17. Retrieved from http://www.acadpharm.org/dos_public/Recommandations_SEance_vaccination_17_10_2012_VF_du_24.10_2012_Conseil.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 48.Expérimentation de la vaccination contre la grippe en pharmacie : les premiers chiffres (2017, June 12). Retrieved February 18, 2018, from https://www.ameli.fr/pharmacien/actualites/experimentation-de-la-vaccination-contre-la-grippe-en-pharmacie-les-premiers-chiffres

- 49.Schmitt H.-J., Booy R., Aston R., Van Damme P., Schumacher R. F., Campins M., Rodrigo C, Heikkinen T, Weil-Olivier C, Finn A, et al. . How to optimise the coverage rate of infant and adult immunisations in Europe. BMC Medicine. 2007;5;11. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-5-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hurel S. Rapport sur la politique vaccinale [rapport public]. 2016, January. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/rapports-publics/164000033/index.shtml

- 51.HCSP Pour une amélioration de la politique vaccinale en France. Paris: Haut Conseil de la Santé Publique; 2012, Retrieved from http://www.hcsp.fr/explore.cgi/avisrapportsdomaine?clefr = 271 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taddio A., Appleton M., Bortolussi R., Chambers C., Dubey V., Halperin S., Hanrahan A, Ipp M, Lockett D, MacDonald N, et al. . Reducing the pain of childhood vaccination: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2010;182(18):E843–E855. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harvey H., Reissland N., Mason J. Parental reminder, recall and educational interventions to improve early childhood immunisation uptake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2015;33(25):2862–80. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Domek G. J., Contreras-Roldan I. L., O'Leary S. T., Bull S., Furniss A., Kempe A., Asturias E. J. SMS text message reminders to improve infant vaccination coverage in Guatemala: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2016;34(21):2437–43. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willis N., Hill S., Kaufman J., Lewin S., Kis-Rigo J., De Castro Freire S. B., Bosch-Capblanch X, Glenton C, Lin V, Robinson P, et al. . “Communicate to vaccinate”: the development of a taxonomy of communication interventions to improve routine childhood vaccination. BMC Int. Health Human Right. 2013;13:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization The guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guthmann J.-P., Fonteneau L., Desplanques L., Lévy-Bruhl D. Couverture vaccinale BCG chez les enfants nés après la suspension de l'obligation vaccinale et suivis dans les PMI de France : enquête nationale 2009. Arch Pediatr. 2010;17(9):1281–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2010.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinot A., Cohen R., Denis F., Gaudelus J., Lery T., Lepetit H., Stahl J.-P. Évolution du taux de couverture vaccinale des enfants de moins de 7ans en France après publication du calendrier vaccinal 2013. Archives de Pédiatrie. 2014;21(12):1389–90. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2014.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biasio L. R., Carducci A., Fara G. M., Giammanco G., Lopalco P. Health Literacy, Emotionality, Scientific Evidence Elements Of An Effective Communication In Public Health. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;0. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1434382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Biasio L. R. Vaccine hesitancy and health literacy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;13(3):701–2. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1243633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Debussche X., Corbeau C., Caroupin J., Fassier M., Ballet D., Balcou-Debussche M., Boegner C. Littératie en santé et précarité : optimiser l'accès à l'information et aux services en santé. L'expérience de Solidarité Diabète. Médecine Des Maladies Métaboliques. 2017;11(8):739–44. doi: 10.1016/S1957-2557(17)30179-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Debussche X., Balcou-Debussche M., Osborne R. CA-090: La littératie en santé : un outil pour une meilleure accessibilité dans le diabète de type 2. Diabetes Metab. 2016;42:A59–A60. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(16)30222-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karafillakis E., Dinca I., Apfel F., Cecconi S., Wűrz A., Takacs J., Suk J, Celentano LP, Kramarz P, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: A qualitative study. Vaccine. 2016;34(41):5013–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Belmin Joel, Bourée P., Camus D., Guiso N., Jeandel C., Trivalle C., Veyssier P. Vaccination in older adults: development of an educational tool, Vaxisenior, in France. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9(sup3):15–20. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dubé E., Gagnon D., MacDonald N. E., SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: Review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simplification et évolution majeure du calendrier … – MesVaccins.net 2013, April 18. Retrieved February 1, 2018, from https://www.mesvaccins.net/web/news/4037-simplification-et-evolution-majeure-du-calendrier-vaccinal-francais-2013

- 67.Vaccination des nourrissons : quels changements en 2018 ? 2018, May 1. Retrieved February 18, 2018, from https://www.ameli.fr/assure/actualites/vaccination-des-nourrissons-quels-changements-en-2018

- 68.HCSP. Avis relatif à la vaccination anti- Méningococcique C. Paris: Haut Conseil de la santé publique. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Levy-Bruhl, D., Perrocheau, A., Mora, M., Taha, M. K., Dromell-Chabrier, S., Beytout, J., Quatresous, I. Vaccination campaign following an increase in incidence of serogroup C meningococcal diseases in the department of Puy-de-Dôme (France). Euro Surveill. 2002;7(5):74–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krypciak, S., Liuu, E., Vincenot, M., Landelle, C., Lesprit, P., Cariot, MA., Mézière, A, Taillandier-Hériche, E, Leroux, JL, Canoui-Poitrine, F, et al. Improvement of pneumococcal immunization coverage in older patients. Rev Med Interne. 2015;36(4):243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baudier, F., Tarrapey, F., Leboube, G. Pilot campaign to promote vaccination: description preliminary results of a regional French program. Med Mal Infect. 2007;37(6):331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rothan-Tondeur, M., Filali-Zegzouti, Y., Golmard, J. L., De Wazieres, B., Piette, F., Carrat, F., Lejeune, B., Gavazzi, G. Randomised active programs on healthcareworkers' flu vaccination in geriatric health care settings in France: The VESTA study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(2):126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]