Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, accounting for more than 60,000 newly diagnosed cases in the United States. Most cases present at an early stage and can be treated with curative intent; however, those who present with advanced disease or who develop metastatic or recurrent disease, have a poor prognosis. Active standard treatments have been identified in the first‐line or adjuvant settings; however, therapeutic options are limited for second‐ or later‐line treatment of the disease. This has prompted interest in molecular testing, particularly for women with recurrent, advanced, or metastatic endometrial cancers.

Abstract

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the U.S. and, although the majority of cases present at an early stage and can be treated with curative intent, those who present with advanced disease, or develop metastatic or recurrent disease, have a poorer prognosis. A subset of endometrial cancers exhibit mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency. It is now recognized that MMR‐deficient cancers are particularly susceptible to programmed cell death protein 1 (PD‐1)/programmed death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) inhibitors, and in a landmark judgement in 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for these tumors, the first tumor‐agnostic approval of a drug. However, less is known about the sensitivity to PD‐1 blockade among patients with known mutations in double‐strand break DNA repair pathways involving homologous recombination, such as those in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Here we report a case of a patient with an aggressive somatic MMR‐deficient endometrial cancer and a germline BRCA1 who experienced a rapid complete remission to pembrolizumab.

Key Points.

Endometrial cancers, and in particular endometrioid carcinomas, should undergo immunohistochemical testing for mismatch repair proteins.

Uterine cancers with documented mismatch repair deficiency are candidates for treatment with programmed cell death protein 1 inhibition.

Genomic testing of recurrent, advanced, or metastatic tumors may be useful to determine whether patients are candidates for precision therapies.

Patient Story

A 42‐year‐old woman with a history of stage IVB Hodgkin's lymphoma, originally diagnosed in 2010, was treated with bevacizumab plus standard chemotherapy (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, and dexamethasone) but relapsed a year after completion. She was then treated on an autologous stem cell transplant and consolidative proton radiation therapy to her mediastinum, all of which completed in January 2013, and from which she achieved a clinical remission. In January of 2015 she presented with irregular vaginal bleeding and underwent an exam under anesthesia, hysteroscopy, and dilatation and curettage, where a diagnosis of endometrioid‐type endometrial cancer, grade 1, was made. She ultimately underwent a total laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy, and final pathology confirmed a T1B, grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma with evidence of lymphovascular invasion and positive pelvic washings. Her family history at this time was only positive for Hodgkin's disease and ductal carcinoma in situ in a half‐sister (who tested negative for a BRCA mutation), breast cancer in a paternal aunt, and prostate cancer in her maternal and paternal uncles. Prior to the scheduled comprehensive surgical staging, she presented with a firm and tender vaginal nodule.

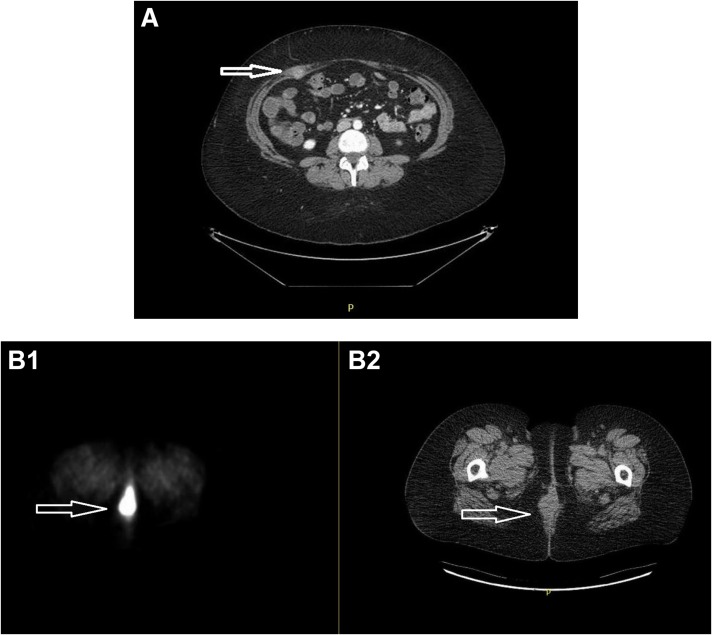

In March 2015, she underwent pelvic and para‐aortic node dissection plus resection of the vaginal mass. The final pathology showed all nodes were negative; the vaginal excision showed endometrioid adenocarcinoma, grade 1, consistent with metastatic disease, with loss of expression of MSH2 and MSH6, consistent with mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency. A month later, she was seen for consultation regarding radiation therapy, at which time a staging positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) was concerning for metastatic disease involving her right rectus muscle (Fig. 1A) and umbilicus. Given her prior treatments for lymphoma, she was started on hormonal therapy using alternating courses of megestrol acetate for 3 weeks followed by tamoxifen for 3 weeks, beginning in May 2015. Unfortunately, 3 months later, she had progression of the right rectus muscle and a second vaginal recurrence. This was treated with radiation therapy to the abdominal wall lesion, vagina, low pelvis, and inguinal basins, all of which completed in November 2015. An attempt to incorporate cisplatin as a radiosensitizer was abandoned due to prolonged myelosuppression. She then underwent resection of the abdominal wall lesion and a radical posterior vulvectomy requiring plastics for reconstruction, all of which completed in January 2016.

Figure 1.

Recurrence identified by Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT). (A): Recurrence involving rectus abdominis on right side following second surgery for node dissection and resection of a vaginal recurrence. (B): Recurrence involving the vagina showing fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity (B1) and demonstrated on CT (B2).

In May 2016, she developed a symptomatic perineal lesion that was intensely FDG avid by PET/CT (Fig. 1B1). Because the lesion recurred following both exposure to chemotherapy (albeit briefly) and radiation therapy, we repeated a biopsy, which showed her tumor had dedifferentiated into a high‐grade Mullerian adenocarcinoma. Given the more aggressive histology in this recurrence, immunohistochemical stains for MMR proteins were repeated and confirmed loss of expression of MSH2 and MSH6 once more, consistent with her primary tumor. Given these findings, she was referred for genetic testing and her tumors sent for genomic analysis.

Molecular Tumor Board

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, accounting for over 60,000 newly diagnosed cases in the U.S. [1]. Although the majority of cases present at an early stage and can be treated with curative intent, those who present with advanced disease, or develop metastatic or recurrent disease, have a poorer prognosis. Although active standard treatments have been identified in the first‐line (or adjuvant setting), to date, there are limited therapeutic options for second‐ or later‐line treatment of this disease. This has prompted interest in molecular testing, particularly for women with recurrent, advanced, or metastatic endometrial cancers, and the utilization of novel strategies and the accompanying search for predictive biomarkers.

Genotyping and General Interpretation

Tumor genomic sequencing performed at the Center for Integrated Diagnostics (Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital) used Anchored Multiplex PCR (AMP) and targeted mutational hotspots and exons from 91 genes (REF: see reference section below). This analysis detected multiple variants, including pathogenic nonsense and frameshift mutations in BRCA2 (p.N1784fs*3, c.5351dupA), TP53 (p.R306*, c.916C>T), and in PTEN (p.R233*, c.697C>T; p.K267fs*9, c.800delA), a well‐described missense variant in FBXW7 (p.R465C, c.1393C>T) that results in loss of function of this tumor suppressor, and a hotspot‐activating mutation in PIK3CA (p.R88Q, c.263G>A). Rare variants of uncertain clinical significance included the following: TP53 p.R267W (c.799C>T), PIK3CA p.R93Q (c.278G>A), APC p.H1349R (c.4046A>G), ARID1A p.T1514M, and p.F2141fs*59 (c. c.4541C>T and 6420delC, respectively), and AURKA splice region variant (c.567‐4G>A). Of these 12 variants, 11 involved C>T (or G>A) transitions or small insertions/deletions at mononucleotide repeats, consistent with the mutational signature associated with defective DNA mismatch repair and microsatellite‐unstable tumors.

Germline testing for BRCA1 and MSH2 was performed at GeneDx (Comprehensive Cancer Panel and MSH2 Exons 1–7 Inversion Analysis) and detected a pathogenic deletion in BRCA1 (p.E23Vfs*17, c.68_69delAG). This variant, also known as BRCA1 185delAG, causes Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome and is one of three main founder mutations in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Testing of the patient's endometrial cancer using the AMP‐based genotyping assay described above detected the BRCA1 germline variant in a heterozygous state, with no evidence of a second hit or of BRCA1 copy loss or loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the tumor.

The patient was negative for germline variants in MSH2, suggesting she did not have Lynch syndrome. Additional tumor sequencing was carried out for the assessment of somatic variants in MSH2 (ColoSeq Tumor Gene Panel, University of Washington). The analysis detected two somatic pathogenic frameshift mutations in MSH2 (p.E56Afs*10, c.161_162insCCGGG; and p.M729Cfs*16, c.2185del) that disrupt the reading frame and result in the insertion of a premature termination codon. These alterations are predicted to compromise protein function and affect DNA mismatch repair, consistent with the loss of MSH2 expression and with the microsatellite instability observed in the tumor.

Functional Significance of the Molecular Alteration

The Cancer Genome Atlas in endometrial cancer suggests that the disease is quite heterogeneous, with recognition of four distinct molecular subtypes: (a) POLE associated with mutation in the DNA polymerase gene E marked by ultramutation; (b) microsatellite instability (MSI) associated with mutations in the DNA mismatch repair machinery, marked by hypermutation; (c) microsatellite stable with low level of DNA copy number changes, marked by endometrioid histology; and (d) DNA copy number high tumors, mostly associated with serous‐like histology but also observed in 25% of high‐grade endometrioid tumors [2].

Defects in any of the key components of the DNA mismatch repair machinery (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2 proteins) leads to the accumulation of large numbers of mutations, due to the inability of the cell to correct mismatched DNA bases arising during replication, recombination, or DNA damage. Microsatellites are highly repetitive sequences of DNA consisting of mono‐ or polynucleotide repeats. These regions are particularly susceptible to mutation during cell division, due to slippage of the DNA polymerase, with resulting insertion or deletion of repeating units. Such errors are corrected by the MMR machinery, but in tumors with defective MMR, microsatellite regions incur many mutations often referred.

Clinical Significance and Utility of the Molecular Alteration

Much has been published about the responsiveness of tumors with MMR deficiency to immune checkpoint inhibitors, including for women with endometrial cancer. As such, patients with tumors harboring multiple genetic alterations that result in a high mutational burden would experience a benefit to PD‐1 blockade. Indeed, although the predictors of response to PD‐1 blockade are not completely established across all tumor types, multiple molecular determinants have been evaluated, including PD‐L1 expression, mutational burden, lymphocytic infiltration, and mutation‐associated neoantigens [3]. In the seminal paper by Diaz et al., the objective response rate among 86 patients with MMR deficiency was 53% (21% complete responses), without discrimination of whether MMR was Lynch or non‐Lynch associated. This report ultimately led to U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of pembrolizumab for MSI tumors, regardless of their site of origin [4].

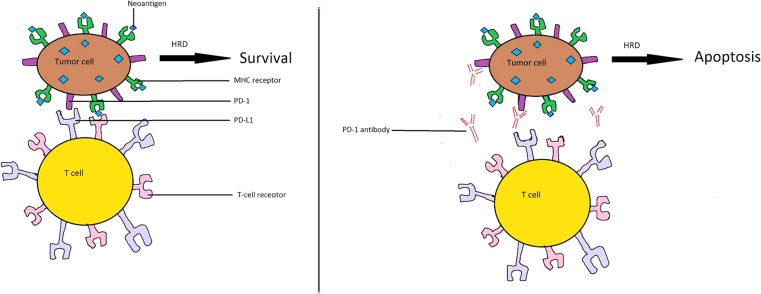

Mutations involving BRCA1 and BRCA2 are associated with homologous recombination deficiency, making them susceptible to apoptosis after exposure to chemotherapy (e.g., platinum agents) and other DNA‐damaging agents, as well as PARP inhibitors. However, less is known about the sensitivity to PD‐1 blockade among patients with known mutations in double‐strand break DNA repair pathways involving homologous recombination, such as those in BRCA1 or BRCA2 [5]. Similar to MMR‐deficient tumors, mutations in BRCA also lead to a higher mutational burden, which may also render tumor cells susceptible to immune‐mediated cytotoxicity resultant from immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sequencing data indicated that the patient's endometrial tumor harbored pathogenic mutations in BRCA1 (germline) and BRCA2 (somatic). Because both variants appear to be heterozygous, we do not anticipate complete inactivation of either tumor suppressor. However, it is tempting to speculate that partial loss of the two genes may result in decreased activity of the BRCA repair pathway and further contribute to the production of tumor neoantigens (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism of increased sensitivity to pembrolizumab. (A): Tumor cell showing PD‐L1 and MHC receptor attached to microsatellite instability‐generated neoantigen. Even in the presence of BRCA mutation‐associated HRD, binding of the T‐cell receptor to tumor‐associated PD‐L1 escapes immune surveillance via binding of PD‐1 to PD‐L1. (B): In the presence of pembrolizumab, binding of PD‐1 to PD‐L1 is blocked, leading to immune‐mediated cytotoxicity generated by binding of the T‐cell receptor to the MHC‐neoantigen complex. This immune‐mediated cytotoxicity may be heightened if HRD is compromised, resulting in increased apoptosis.

Abbreviations: HRD, homologous recombination deficiency; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; PD‐1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD‐L1, programmed death‐ligand 1.

Patient Update

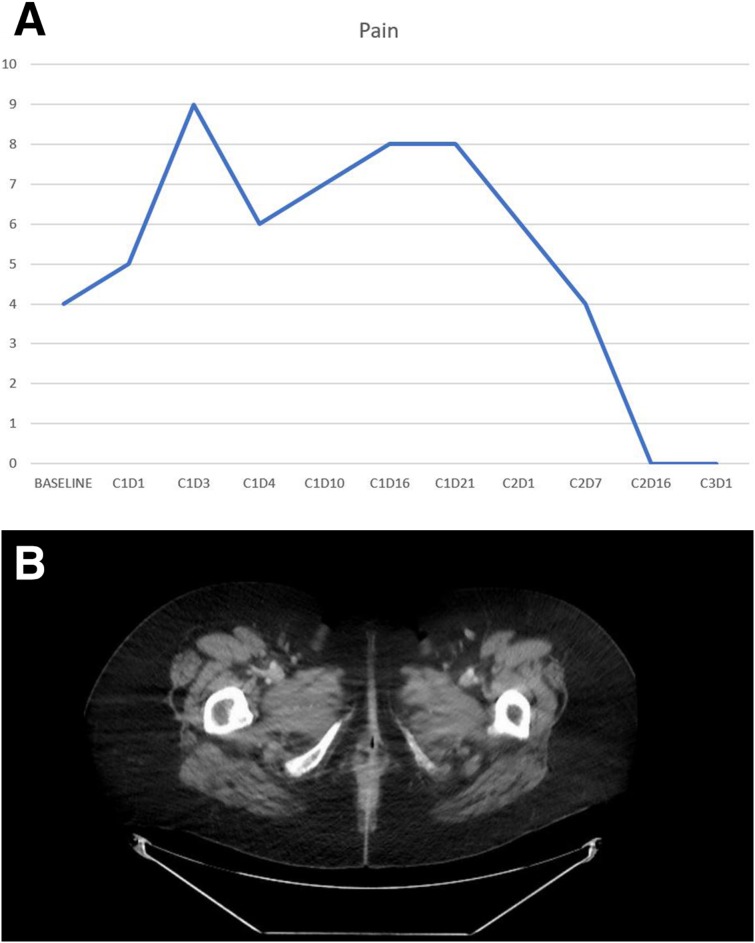

Given the patient was not able to tolerate cisplatin as a radiosensitizer, the team did not feel systemic therapy was a safe option. Unfortunately, her disease had also proven resistant to radiation therapy, and attempts for surgical control proved ineffective. In a final attempt to treat her symptomatic disease, she began pembrolizumab in June 2016 (2 mg/kg administered every 3 weeks). Following one dose of treatment, she had a 30% shrinkage of her tumor on exam, and by the start of her third cycle, her pain completely resolved (Fig. 3A). Repeat imaging after four cycles showed complete resolution of her perineal mass, consistent with a complete response. She remains in remission 13 months after initiation of treatment (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Clinical and radiologic evidence of benefit on pembrolizumab. (A): Patient‐reported pain scores during the first three cycles of pembrolizumab. Note the dramatic resolution of pain by C2D16. (B): Computed tomography scan after four cycles of pembrolizumab, showing a complete remission, which continues 13 months after start of treatment.

Conclusion

We report the case of a BRCA1‐mutation carrier with an aggressive endometrial carcinoma. The curious occurrence of a pathogenic BRCA2 variant in her MMR‐deficient tumor might have led to partial impairment of the BRCA repair pathway. This combination may explain her expeditious and sustained response to PD‐1 inhibition.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: See the related commentary, “Implementing Keytruda/Pembrolizumab Testing in Clinical Practice,” by Dmitry Ratner and Jochen K. Lennerz, on page 647 of this issue.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Don S. Dizon, Dora Dias‐Santagata, Amy Bregar, Leif Ellisen, Michael Birrer, Marcela DelCarmen

Provision of study material or patients: Don S. Dizon, Laura Sullivan, Jennifer Filipi, Elizabeth DiTavi, Lucy Miller, Leif Ellisen, Marcela DelCarmen

Collection and/or assembly of data: Don S. Dizon, Dora Dias‐Santagata, Amy Bregar, Laura Sullivan, Marcela DelCarmen

Data analysis and interpretation: Don S. Dizon, Dora Dias‐Santagata, Leif Ellisen, Michael Birrer

Manuscript writing: Don S. Dizon, Dora Dias‐Santagata, Amy Bregar, Laura Sullivan, Jennifer Filipi, Elizabeth DiTavi, Lucy Miller, Leif Ellisen, Michael Birrer, Marcela DelCarmen

Final approval of manuscript: Don S. Dizon, Dora Dias‐Santagata, Amy Bregar, Laura Sullivan, Jennifer Filipi, Elizabeth DiTavi, Lucy Miller, Leif Ellisen, Michael Birrer, Marcela DelCarmen

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013;497:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD‐1 blockade. Science 2017;357:409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication. Available at https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm560040.htm. Accessed November 20, 2017.

- 5. Muggia F, Safra T. ‘BRCAness’ and its implications for platinum action in gynecologic cancer. Anticancer Res 2014;34:551–556. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]