Abstract

Background

Dual-source computed tomography (CT) can evaluate left ventricular (LV) dyssynchrony, myocardial scar and coronary venous anatomy in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT).

Objective

We aim to determine if dual-source CT predicts clinical CRT outcomes and reduces intra-procedural time.

Methods

In this prospective study, 54 patients scheduled for CRT (age 63±11, 74% male) underwent pre-procedural CT to assess their venous anatomy as well as CT-derived dyssynchrony metrics and myocardial scar. Based on the 1:1 randomization, the implanting physician had pre-implant knowledge of the venous anatomy in half the patients. In blinded analyses, we measured time-to-maximal wall thickness and inward motion to determine 1) CT global and segmental dyssynchrony and 2) concordance of lead location to regional LV mechanical contraction. Endpoints were 6-month CRT response by Heart Failure Clinical Composite Score and 2-year major adverse cardiac events (MACE).

Results

There were 72% CRT responders and 17% with MACE. Two wall motion dyssynchrony indices (global and opposing anteroseptal-inferolateral walls) predicted MACE (p<0.01). Lead location concordant to regions of maximal wall thickness was associated with less MACE (p<0.01). No CT metrics predicted the 6-month CRT response (all p=NS). Myocardial scar (43%), posterolateral wall scar (28%) and total scar burden did not predict outcomes (all p=NS). Pre-knowledge of CT coronary venous anatomy did not reduce implant or fluoroscopy time (both p=NS).

Conclusions

Two CT dyssynchrony metrics predicted 2-year MACE, and LV lead location concordant to regions of maximal wall thickness were associated with less MACE. Other CT factors had little utility in CRT.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

Keywords: computed tomography, dyssynchrony, imaging, coronary veins, cardiac resynchronization therapy

Journal Subject Codes: [30] CT and MRI, [150] Imaging, [106] Electrophysiology

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has worldwide acceptance as adjuvant treatment for patients with refractory severe heart failure (HF), left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction, and wide QRS duration. 1 However, about 1/3 of patients do not demonstrate clinical improvement. 2 Intraventricular (or LV) dyssynchrony, myocardial scar, and their relationship to LV lead location are believed to be major determinants of CRT response. 2, 3 However, there remains no gold standard for dyssynchrony assessment and no proven predictors of CRT response.

Cardiac dual-source computed tomography (CT) may be an ideal noninvasive modality that provides both functional and anatomical information, pertinent to the LV myocardium. CT may be used to measure LV dyssynchrony, quantify and locate myocardial scar, while providing detailed coronary venous information. In an earlier study, we have reported on a reproducible quantitative CT-based method for dyssynchrony assessment using early generation single-source cardiac CT scanners with temporal resolution of 165 milliseconds (ms) that can provide only a rough estimate of the extent of LV dyssynchrony. 4 Dual-source CT, with its improved mean temporal resolution of 60 ms using bi-segment reconstruction, 5 is adequate for dyssynchrony assessment by providing complete 3-dimensional (3D) imaging of the entire heart and excellent delineation of both endocardial and epicardial boundaries for assessing LV wall thickness, wall motion, and volume. CT allows for myocardial scar analysis using wall motion analysis, early first-pass perfusion and late delayed enhancement images. 6 Moreover, dual-source CT has high isotropic spatial resolution and can image the coronary veins with great detail.

Thus, we sought to determine whether dual-source CT-based dyssynchrony and myocardial scar can be used to predict clinical CRT response. Additionally, we evaluated if pre-implant knowledge of the coronary venous anatomy would be useful in reducing intra-procedural time.

METHODS

Study Population and Protocol

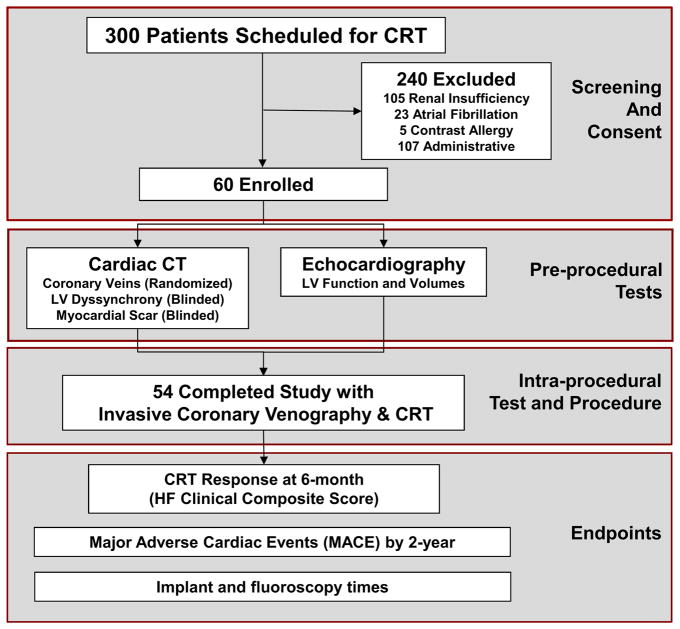

The “Dual-Source Computed Tomography to Improve Prediction of Response to Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy” (DIRECT, clinical trial identifier NCT01097733) study was a prospective double-blind randomized study of 60 refractory HF patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Class II–IV, echocardiographic (Echo) ejection fraction (EF) ≤35%, and electrocardiographic (ECG) QRS duration ≥120 ms undergoing CRT implantation. Supplemental Data 1 details the sample size and power analysis. Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram of DIRECT. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Supplemental Table 1. Study protocol and follow-ups are detailed in Supplemental Data 2. Our institutional review board approved the study protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. Study Design Flow Diagram with Screening, Enrollment, Pre- and Intra-Procedural Tests, and Follow-up of the DIRECT Participants.

CRT denotes cardiac resynchronization therapy; LV, left ventricular; HF, heart failure.

CT Scan Protocol

CT image acquisition was performed on the first and second-generation dual-source CT scanner (Somatom Definition and Definition FLASH; Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany). The imaging protocol was specifically tailored for (1) coronary venous phase imaging without nitrates in the caudo-cranial direction to minimize visual interference from the coronary arteries, (2) retrospective gating using a bi-segment reconstruction acquisition mode to achieve the best temporal resolution for dyssynchrony assessment, and (3) a 10-minute delayed noncontrast prospectively triggered scan for myocardial scar assessment (Supplemental Data 3).

CT Dyssynchrony Analyses

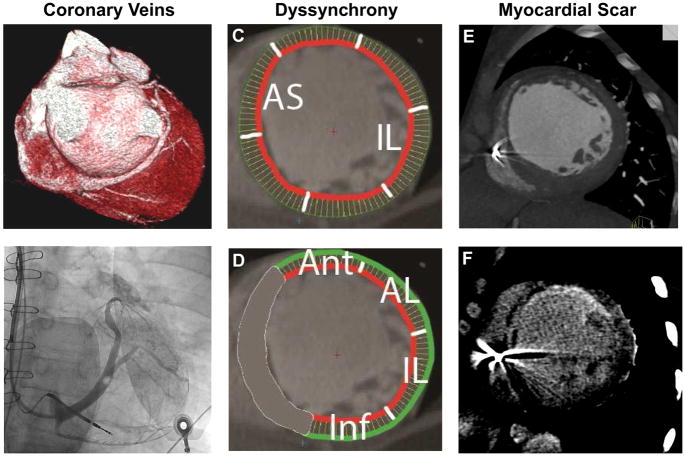

For the CT dyssynchrony measurements, we created the LV short-axis images from the multiphase reformatted reconstructions (8 mm thick, 5% increments, 20 phases) and defined the endocardial and epicardial boundaries throughout the cardiac cycle, excluding the LV outflow tract, using QMassCT 7.1 software (Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, the Netherlands) by methods previously described. 4 CT dyssynchrony indices were measured using global and segmental time to maximal wall thickness, global and segmental time to maximal inward motion, and time to minimum systolic volume (Figure 2). 4 Specifically, we measured time to maximal wall thickness and inward motion to determine CT global and segmental dyssynchrony indices.

Figure 2.

CT (A) and invasive coronary venography (B), CT dyssynchrony by wall motion (C) and wall thickness (D), and CT myocardial scar by first-pass perfusion (E) and delayed enhancement (F).

To determine whether there was concordance of lead location to regional LV mechanical contraction, we first calculated the mean times to (1) maximum wall thickness and (2) maximal wall motion of each segment based on an 8-segment model (basal and mid anterior, inferior, anterolateral, inferolateral segments). From these 8 basal and mid segments, which are deemed most optimal for LV lead placement, 3 we determine the segment with the latest mean times to either maximal wall thickness or wall motion. Final LV lead location was determined by region (basal, mid or apical) and coronary vein from the invasive coronary venography. We compared the segment of latest regional LV mechanical contraction (wall thickness or wall motion) to the site of final lead location. The final lead location was deemed as concordant (same segment), adjacent (one segment apart), or remote (at least two segments apart) to the segment of latest regional LV mechanical contraction.

CT Myocardial Scar Analyses

We performed both qualitative and quantitative CT myocardial scar analyses. For qualitative analysis, myocardial scar was defined as regions of akinesis or dyskinesis on wall motion analysis, hypoenhancement on early first-pass perfusion, wall thickness of <6 mm during maximal systole, or hyperenhancement on late delayed enhancement using the American Heart Association 17-segment LV model (Figure 2). We evaluated for the presence of myocardial scar, presence of scar in the posterolateral wall (defined as segments 4, 5, 10, 11, 15, 16), and relationship of LV lead location and scar. For quantitative analysis, the extent of total scar burden was quantified as a percentage of left ventricular mass (regions of interest [ROIs] drawn over the hypoenhanced area on early first-pass perfusion and hyperenhanced area on late delayed enhancement for myocardial scar mass, with LV mass determined from endocardial and epicardial contours, as previously described.6

Coronary Vein Analysis by CT and Invasive Coronary Venography

A total of 54 patients underwent both CT venography preoperatively and invasive coronary venography (ICV) intraoperatively prior to LV lead placement. For CT venography and ICV, the coronary venous anatomy classification was based on the different venous territories draining the left ventricular myocardium (Supplemental Data 4). 7

2D Echocardiography Metrics

Baseline and follow-up 2D Echo examinations were performed by the MGH Echo Laboratory (Supplemental Data 5).

Endpoints

For the endpoint of 6-month CRT response, we used the HF Clinical Composite Score (CCS, Supplemental Data 6). An outcome panel consisting of two cardiologists, blinded to the CT analysis, determined the clinical response of each subject based on review of the medical record, with disagreement resolved by a third cardiologist.

For the endpoint of 2-year major adverse cardiac event (MACE), we included the composite endpoint of death, left ventricular assist device (LVAD), cardiac transplantation, and heart failure hospitalization. Endpoints for the randomized pre-knowledge of CT venous anatomy included implant and fluoroscopy times.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range [IQR] for continuous variables and as frequency and percentages for nominal variables. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test; continuous variables are compared using a t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Additional statistical analyses are in Supplemental Data 7. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline patient characteristics are typical of CRT patients and are shown in Table 1 and as stratified by CRT response (Supplemental Table 2). The temporal resolution of the bi-segment CT scans was 63.8±6.1ms (dual-source CT 1st generation 72.5±2.7 ms; 2nd generation 62.2±5.2 ms). The effective radiation dose of the retrospective CT scan was 11.7±5.0 mSv, and total radiation dose with delayed imaging was 13.5±5.0 mSv. The median follow-up period was 23.6 months [range 9–24 months].

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Total (n=54) | |

|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |

| Age, years | 63±11 |

| Male, n (%) | 40 (74%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.4 ± 5.8 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 13 (24%) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 27 (50%) |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 20 (37%) |

| History of atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 8 (15%) |

| History of MI, n (%) | 13 (24%) |

| History of CABG, n (%) | 10 (19%) |

| History of stent, n (%) | 14 (26%) |

| Coronary disease (composite), n (%) | 21 (39%) |

| Prior Device, n (%) | 27 (50%) |

| PPM, n (%) | 4 (7%) |

| ICD, n (%) | 23 (43%) |

| NYHA, | |

| I, n (%) | 0 (0%) |

| II, n (%) | 9 (17%) |

| III, n (%) | 44 (81%) |

| IV, n (%) | 1 (2%) |

| Minnesota Quality of Life Score | 34 [17, 59] |

| Six-minute walk test, feet | 988±404 |

| Medications | |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 42 (78%) |

| BB, n (%) | 50 (93%) |

| Spironolactone, n (%) | 20 (37%) |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 36 (67%) |

| Laboratory | |

| Cr, mg/dL | 1.1±0.2 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 893 [370, 1683] |

| ECG parameters | |

| QRS duration, ms | 162±22 |

| QRS duration > 150 ms | 38 (70%) |

| LBBB, n (%) | 40 (74%) |

| Paced rhythm, n (%) | 5 (9%) |

| Echocardiography parameters | |

| LVEF, % | 27±7 |

| LV dimensions, mm | |

| End-diastole (EDD) | 63±10 |

| End-systole (ESD) | 54±10 |

| LV volumes, cm3, n=53 | |

| End-diastole (EDV) | 231±93 |

| End-systole (ESV) | 170±81 |

| LV Lead Type | |

| Unipolar, n (%) | 1 (2%) |

| Bipolar, n (%) | 43 (80%) |

| Quadripolar, n (%) | 10 (19%) |

Abbreviations in Supplemental Data 8.

For our endpoint of 6-month CRT response, defined as improvement of adjudicated HF Clinical Composite Score, there were 39 (72%) CRT responders and 15 (28%) nonresponders. There were no differences in baseline demographics, medication history, laboratory values of renal function and NT-proBNP, ECG or Echo parameters including EF and LV volumes, or LV lead types between CRT responders and nonresponders (Supplemental Table 2, all p=NS).

For our endpoint of 2-year MACE, there were 9 (17%) patients who a MACE by two years: death (n=5), LVAD (n=1), or HF hospitalization (n=9). No participant underwent heart transplantation by end of the study period.

CT Dyssynchrony and CRT Outcomes

Supplemental Table 3 shows the differences in the CT dyssynchrony metrics and CRT outcomes. None of the CT dyssynchrony metrics predicted CRT response at 6-months (all p=NS). Two wall motion dyssynchrony indices (global wall motion [GWMDI] and segmental anteroseptal-inferolateral wall motion [AS-IL WMDI]) were associated with two-year MACE (age-adjusted p<0.01; Table 2). The survival c statistics of GWMDI was 0.65 for MACE; while the c statistics of AS-IL WMDI was 0.75.

Table 2.

CT Dyssynchrony Metrics and CRT Outcomes

| 6-month CRT Response | 2-Year MACE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| CT Dyssynchrony Indices (DI) | Age-adjusted OR* (95% CI) | p-value | Age-adjusted HR* (95% CI) | p-value |

| Time-to-Maximal Wall Thickness | ||||

| Global Wall Thickness [GWTDI] | 1.2 (0.24–5.8) | 0.85 | 0.82 (0.15–4.6) | 0.82 |

| Segmental Opposing Wall Thickness | ||||

| Anterior-Inferior [A-I WTDI] | 1.1 (0.27–4.3) | 0.92 | 0.93 (0.24–3.6) | 0.92 |

| Inferoseptal-Anterolateral [IS-AL WTDI] | 0.87 (0.28–2.7) | 0.80 | 0.60 (0.17–2.1) | 0.43 |

| Anteroseptal-Inferolateral [AS-IL WTDI] | 1.6 (0.38–6.5) | 0.53 | 0.63 (0.14–2.8) | 0.54 |

| Time-Peak Inward Wall Motion | ||||

| Global Wall Motion [GWMDI] | 0.34 (0.07–1.6) | 0.17 | 0.09 (0.02–0.55) | 0.009 |

| Segmental Opposing Wall Motion | ||||

| Anterior-Inferior [A-I WMDI] | 1.1 (0.53–2.5) | 0.74 | 0.65 (0.30–1.4) | 0.28 |

| Inferoseptal-Anterolateral [IS-AL WMDI] | 1.0 (0.28–3.9) | 0.95 | 0.40 (0.10–1.7) | 0.21 |

| Anteroseptal-Inferolateral [AS-IL WMDI] | 0.40 (0.13–1.2) | 0.10 | 0.15 (0.05–0.50) | 0.002 |

| Time-Minimum Systolic Volume | ||||

| Global Systolic Volume [GSVDI] | 0.47 (0.16–1.4) | 0.17 | 0.30 (0.09–1.1) | 0.06 |

All CT metrics were log-transformed milliseconds.

Abbreviations in Supplemental Data 9.

There were no differences in any of the CT dyssynchrony metrics when analyzing by subgroups of ischemic vs nonischemic, left bundle branch block (LBBB) vs non-LBBB, QRS duration >150 ms, median QRS duration, paced vs nonpaced, male vs female, primary de novo device vs device upgrade; NYHA II vs NYHA III–IV for any of the endpoints (all p=NS).

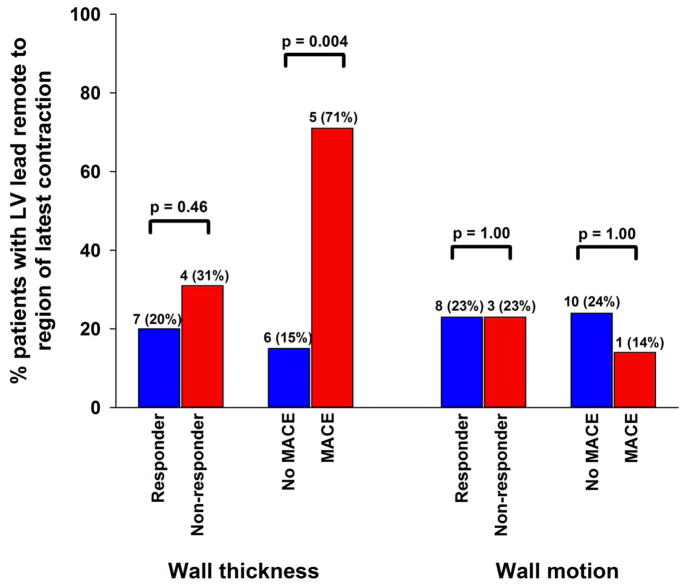

Importantly, in regional LV mechanical contraction analysis, patients with lead location remote from regions of maximal wall thickness had more MACE, while those with lead location concordant or adjacent to regions of maximal wall thickness had less MACE (p=0.004, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Regional LV Mechanical Contraction and CRT Outcomes

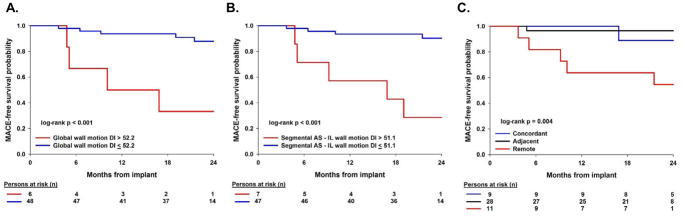

Figure 4 depicts the Kaplan-Meier curves of the 3 CT predictors of MACE: GWMDI optimal cutpoint of 52.2 ms (c-statistic 0.69), segmental AS-IL WMDI optimal cutpoint of 51.1 ms (c-statistic 0.73), and regional wall thickness LV contraction relationship to LV lead location (c-statistic 0.64).

Figure 4.

Kaplan Meier of (A) global inward wall motion optimal cutpoint, (B) segmental inward wall motion optimal cutpoint and (C) regional mechanical contraction using wall thickness.

Myocardial Scar and CRT Outcomes

We performed qualitative assessment for myocardial scar with CT using early first pass rest perfusion, wall motion abnormalities, wall thinning (<6 mm) and delayed hyperenhancement (Supplemental Table 4). Overall, there were 23 (43%) patients identified as having myocardial scar and 15 (28%) with posterolateral wall scar. Neither presence of myocardial scar or posterolateral scar was predictive of CRT response or MACE (all p=NS).

In examining LV lead location over scar and posterolateral wall scar for predicting CRT response or MACE, only 1 (2%) patient had LV lead tip over scar, and while this patient was a CRT nonresponder, we are underpowered to assess the association CRT response and LV lead tip over scar.

There were no significant difference in overall scar burden in examining extent of scar to CRT response and MACE (all p=NS, Supplemental Table 5). In those with scar, CRT nonresponders and those with MACE had higher scar burden by first pass perfusion and delayed enhancement, though the difference was statistically non-significant.

Preknowledge of CT Coronary Venous Anatomy

In assessing if pre-procedural knowledge of CT coronary venous anatomy reduced implant and fluoroscopy time, 26 (48%) patients were randomized to the pre-knowledge CT strategy while the implanting physicians for 28 (52%) patients remained blinded to the CT venous anatomy. Pre-knowledge of CT coronary venous anatomy did not reduce implant time (160 [130, 180] minutes vs 145 [125, 190] minutes, p=0.54) or fluoroscopy time (26.8 [20.0, 45.6] minutes vs 22.5 [17.1, 30.7] minutes, p=0.28) as compared to standard implantation strategy.

DISCUSSION

In the DIRECT study, while we did not find any CT parameters to predict 6-month CRT response, we found two CT dyssynchrony metrics using inward wall motion (one global and the other opposing wall of anteroseptal-inferolateral) to be associated with two-year MACE. Additionally, concordance of lead location to regional LV mechanical contraction by maximal wall thickness was associated with less MACE. In the CT analysis with myocardial scar, the presence of myocardial scar, posterolateral scar or total scar burden were not predictive of CRT response or MACE. Finally, there was no difference in either implant or fluoroscopy times when comparing patients randomized to pre-knowledge of CT coronary venous anatomy to standard implantation strategy.

Previous work from our group using single-source CT, with poorer temporal resolution of 165 ms, showed that CT may provide a rough estimate of CT dyssynchrony when comparing HF patients to normal controls. 4 In the DIRECT study, we examined whether dual-source CT with its improved temporal resolution of 64 ms can discern a difference in dyssynchrony between CRT responders, who should have a greater degree of LV dyssynchrony, as compared to nonresponders. 2 While our results found no CT metrics predicted 6-month CRT response using the HF CCS, our findings are congruous with the negative results of the 12 established Echo-derived metrics from the PROSPECT trial. 8 For our endpoint of 6-month CRT response, we selected the HF CCS, which is the most accepted measure for defining CRT response as it uses both subjective and objective parameters of HF outcomes.

In converse to the HF CCS, the 2-year composite endpoint of MACE (which includes HF hospitalization, LVAD, cardiac transplant, and death) is a “harder” longitudinal objective endpoint, and arguably provides more important definitive prognostic information. When examining the endpoint of 2-year MACE, we found that two CT metrics (global wall motion and opposing AS-IL wall motion indices) were associated with this more objective and clinically robust MACE endpoint. For the global indices, wall motion analysis of dyssynchrony which uses endocardial borders only was associated with MACE, while wall thickness which uses both endocardial and epicardial borders were not. These findings are not surprising since endocardial-based wall motion metrics have been previously reported with Echo metrics 8 as an established intraventricular dyssynchrony measure, while endo- and epicardial based wall thickness has not been previously validated as a dyssynchrony metric. This reinforces our findings that the opposing AS-IL wall motion CT dyssynchrony metric portends a worse prognosis with 2-year MACE as compared to the other segmental wall pairs.

The impact of LV lead location and its relationship to the site of latest mechanical activation has emerged as a determinant of CRT response, 9 with optimal lead positioning in the region of latest mechanical delay (typically basal or mid segments of the lateral or posterolateral wall) for the highest yield of reverse remodelling, in contrast to LV apical pacing which is associated with detrimental CRT outcomes. 10 However, there is significant variation in the final LV pacing site among patients undergoing CRT, 11 and thus a more individualized approach using image guidance to target the optimal LV lead pacing site is desirable. 12 In the regional mechanical contraction analysis of the DIRECT study, we found that LV lead location concordant or adjacent to regions of maximal wall thickness was associated with less MACE. Our finding is consistent with previous data using Echo-guided CRT placement from the TARGET trial, where the greatest benefit for the combined endpoint of death and heart failure-related hospitalization was found in patients with a concordant LV lead, with substantially lower rates in patients with an LV lead remote from the latest site of contraction. 3 Similar results were observed in smaller pilot studies of less than 18 patients each using CT13 and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).14

Of note, lower MACE was associated with regional mechanical contraction using maximal wall thickness but not wall motion. Whereby the wall motion analysis only includes the endocardial border, the wall thickness analysis incorporates the entire LV myocardium and its intrinsic wall mechanics and myocardial contractile force. Our data provides compelling evidence that further larger studies geared towards a targeted imaging-guided approach using CT-based regional mechanical contraction analysis by wall thickness to determine the region of most delayed contraction are warranted.

With respect to the effect of myocardial scar on CRT outcomes, we found no association between the presence, location or extent of CT-based myocardial scar to CRT outcomes. This is in contrast to other studies where scar was examined by nuclear or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. 6, 15 One explanation may be that cardiac CT is inferior to the other imaging modalities for the detection of myocardial scar. Additionally, we may be underpowered for the scar analysis due to the low MACE rates. Interestingly, when examining the relationship of lead tip location over scarred myocardium, we did observe one patient who had the lead tip positioned directly over scar and was deemed a CRT nonresponder. It would be interesting to see if there was a true association between lead placement over scar and CRT outcomes with a larger sample size.

Notably, the pre-knowledge of the coronary venous anatomy by cardiac CT did not impact the implant or fluoroscopy time in comparison to the randomized group, without any prior information of the patients’ venous anatomy. This may be attributable to the skilled operators at our large tertiary medical center, whose extensive clinical experience may confound any potential differences. Also, the implant approach at our institution is often individualized with an attempt to target the region with greatest electrical delay. Less experienced operators and the use of a purely anatomical implant approach could benefit from pre-procedural knowledge of the coronary venous tree and thereby opt to pursue CT imaging beforehand. While there was no difference in implantation or fluoroscopy time, factors such as physician’s confidence with pre-knowledge of CT coronary venous anatomy, are unaccounted for and may make pre-imaging of the coronary venous system by CT still desirable. Moreover, pre-knowledge of coronary veins by cardiac CT remains an appropriate indication based prior to placement of a biventricular pacemaker, particularly in cases of unsuccessful LV lead attempts due to coronary venous stenosis or challenging anatomy as well as LV lead revision to assess whether there are appropriate veins to target.

The issue of radiation exposure from CT merits discussion. The mean cumulative radiation dose for the CT scan in DIRECT, which includes both a functional cine and delay acquisitions, was 13.5 mSv, which is comparable to the ubiquitous nuclear stress test.16 In our study, both first-generation 64-slice and second-generation 128-slice dual-source CT scanners were used. Newer third-generation 192-slice dual-source scanners, which has larger detectors and even faster temporal resolution, are now available and allow for similar scanning of the heart with functional cine and delay scans with a 40% reduction of radiation dose to 8 mSv.17 While alternative imaging strategies with echocardiography and CMR portends no radiation exposure, the benefit of CT is its quick imaging time (typically <15 minutes for an entire study) and excellent spatial resolution for 4-dimensional imaging of the heart that is least prone to operator-dependency and patient-related factors such as inadequate acquisition windows, varying angle planes, long scan time of complex protocols, and metal artifacts or incompatibility. CT technology continues to advance to faster scanners with even less radiation and continued research in the CRT cohort may lead to a favorable benefit-risk profile for these end-stage NYHA Functional Class II–IV patients to have an imaging-guided approach for LV lead placement.

Limitations

There are several notable limitations to our study. Despite our small sample size and MACE rate, we found an association with 2-year MACE and CT metrics, though our analyses related to global and regional wall motion indices and myocardial scar should be interpreted with caution. Our results are limited to a single large tertiary center as well as a single CT vendor, and thus may not be applicable to smaller hospitals or to facilities using CT scanners with poor temporal resolution or different CT vendors. Our results cannot be extrapolated to patients with atrial fibrillation or renal impairment as these comorbidities met exclusion criteria for our study. Because we did not want to influence the CRT response rate from our power calculation, we elected to not guide operators with the CS anatomy and LV lead placement. Thus, a limitation in the design of the study is that the information regarding the CS anatomy and latest areas of LV activation were not given to the operators. Multisite or multipoint pacing were not available at the time we conducted our study. Future larger studies designed to examine imaging-guided targeted approach for LV lead location at site of latest activation and its adjacent sites with multisite or multipoint pacing would be of interest.

CONCLUSIONS

CT dyssynchrony wall motion metrics and regional mechanical contraction analysis, with LV lead location concordant to regions of maximal wall thickness were associated with 2-year MACE but not 6-month CRT response. CT-based myocardial scar was not associated with CRT response or MACE, but this may be limited to small sample size. Pre-knowledge of coronary venous anatomy did not significantly reduce implant or fluoroscopy time. Our study provides additional insight into the issue of CRT nonresponse and suggests that an imaging-guided approach for LV lead concordance needs further prospective evaluation with larger studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: The study was supported by NIH/NHLBI K23HL098370 and Abbott (formerly St. Jude Medical). Dr. Truong also received support from the NIH L30HL093896 and in-kind support from Medis Medical Imaging Systems.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Truong received grant support from Ziosoft, USA, and was consultant to American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Aralez Pharmaceuticals, and HeartFlow. Dr. Cheung has received speaker honoraria from Biotronik and Medtronic, research grant support from Biotronik and fellowship grant support from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Heist receives grant support from Boston Scientific and St. Jude Medical; and serves as consultant for Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Pfizer, and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Hoffmann receives grant support from Heart Flow and is a consultant for Abbott. Dr. Singh receives grant support from St. Jude Medical, and Boston Scientific Corp. JS consults for LivaNova, St. Jude Medical, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Impulse dynamics, Biotronik and EBR Inc. All other authors have no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vardas PE, Auricchio A, Blanc JJ, et al. Guidelines for cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force for cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2256–2295. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bax JJ, Abraham T, Barold SS, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: Part 1--issues before device implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2153–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan FZ, Virdee MS, Palmer CR, Pugh PJ, O’Halloran D, Elsik M, Read PA, Begley D, Fynn SP, Dutka DP. Targeted left ventricular lead placement to guide cardiac resynchronization therapy: the TARGET study: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1509–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truong QA, Singh JP, Cannon CP, et al. Quantitative analysis of intraventricular dyssynchrony using wall thickness by multidetector computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2008;1:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flohr TG, McCollough CH, Bruder H, et al. First performance evaluation of a dual-source CT (DSCT) system. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:256–268. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2919-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieman K, Shapiro MD, Ferencik M, Nomura CH, Abbara S, Hoffmann U, Gold HK, Jang IK, Brady TJ, Cury RC. Reperfused myocardial infarction: contrast-enhanced 64-Section CT in comparison to MR imaging. Radiology. 2008;247:49–56. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2471070332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blendea D, Shah RV, Auricchio A, Nandigam V, Orencole M, Heist EK, Reddy VY, McPherson CA, Ruskin JN, Singh JP. Variability of coronary venous anatomy in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy: a high-speed rotational venography study. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung ES, Leon AR, Tavazzi L, et al. Results of the Predictors of Response to CRT (PROSPECT) Trial. Circulation. 2008;117:2608–2616. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ypenburg C, van Bommel RJ, Delgado V, Mollema SA, Bleeker GB, Boersma E, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ. Optimal left ventricular lead position predicts reverse remodeling and survival after cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1402–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh JP, Klein HU, Huang DT, et al. Left ventricular lead position and clinical outcome in the multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial-cardiac resynchronization therapy (MADIT-CRT) trial. Circulation. 2011;123:1159–1166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derval N, Steendijk P, Gula LJ, et al. Optimizing hemodynamics in heart failure patients by systematic screening of left ventricular pacing sites: the lateral left ventricular wall and the coronary sinus are rarely the best sites. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:566–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saba S, Marek J, Schwartzman D, Jain S, Adelstein E, White P, Oyenuga OA, Onishi T, Soman P, Gorcsan J. Echocardiography-guided left ventricular lead placement for cardiac resynchronization therapy: results of the Speckle Tracking Assisted Resynchronization Therapy for Electrode Region trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:427–434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behar JM, Rajani R, Pourmorteza A, et al. Comprehensive use of cardiac computed tomography to guide left ventricular lead placement in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:1364–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen UC, Mafi-Rad M, Aben JP, Smulders MW, Engels EB, van Stipdonk AM, Luermans JG, Bekkers SC, Prinzen FW, Vernooy K. A novel approach for left ventricular lead placement in cardiac resynchronization therapy: Intraprocedural integration of coronary venous electroanatomic mapping with delayed enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ypenburg C, Schalij MJ, Bleeker GB, Steendijk P, Boersma E, Dibbets-Schneider P, Stokkel MP, van der Wall EE, Bax JJ. Impact of viability and scar tissue on response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in ischaemic heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:33–41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truong QA, Hayden D, Woodard PK, Kirby R, Chou ET, Nagurney JT, Wiviott SD, Fleg JL, Schoenfeld DA, Udelson JE, Hoffmann U. Sex differences in the effectiveness of early coronary computed tomographic angiography compared with standard emergency department evaluation for acute chest pain: the rule-out myocardial infarction with Computer-Assisted Tomography (ROMICAT)-II Trial. Circulation. 2013;127:2494–2502. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faure ME, Swart LE, Dijkshoorn ML, Bekkers JA, van Straten M, Nieman K, Parizel PM, Krestin GP, Budde RPJ. Advanced CT acquisition protocol with a third-generation dual-source CT scanner and iterative reconstruction technique for comprehensive prosthetic heart valve assessment. Eur Radiol. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.