Abstract

Background & Aims

It is unclear how long pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs) are present before diagnosis. Patients with PDAC usually develop hyperglycemia and diabetes before the tumor is identified. If early invasive PDACs are associated with hyperglycemia, the duration of hyperglycemia should associate with the time that they have had the tumor.

Methods

We collected data on patients with PDACs from medical databases in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 2000 through 2015 and from the Mayo Clinic’s tumor registry, from January 1, 1976 through January 1, 2017. We compared glycemic profiles of patients with PDAC (cases) compared to patients without cancer, matched for age and sex (controls). We analyzed temporal fasting blood glucose (FBG) profiles collected for 60 months before patients received a PDAC diagnosis (index date) (n=219) (cohort A), FBG profiles of patients with resected PDAC (n=526) stratified by tumor volume and grade (cohort B), and temporal FBG profiles of patients with resected PDACs from whom long-term FBG data were available (n=103) (cohort C). The primary outcome was to estimate duration of presence of invasive PDAC before its diagnosis based on hyperglycemia, defined as significantly higher (P<.05) FBG levels in cases compared to controls.

Results

In cohort A, the mean FBG did not differ significantly between cases and controls 36 months before the index date. Hyperglycemia was first noted 36–30 months before PDAC diagnosis in all cases, those with or without diabetes at baseline and those with or without resection at diagnosis. FBG level increased until diagnosis of PDAC. In cohort B, the mean FBG did not differ significantly in controls vs cases with PDACs below 1.0 cc. The smallest tumor volume associated with hyperglycemia was 1.1–2.0 cc; FBG level increased with tumor volume. FBG varied with tumor grade: well- or moderately differentiated tumors (5.8 cc) produced the same FBG levels as smaller, poorly differentiated tumors (1.5 cc) (P<.001). In cohort C, the duration of pre-diagnostic hyperglycemia for cases with large-, medium-, or small-volume PDACs was 36–24, 24–12, and 12–0 months, respectively. PDAC resection resolved hyperglycemia, regardless of tumor location.

Conclusions

In a case–control study of patients with PDAC from 2 databases, we associated FBG level with time to PDAC diagnosis and tumor volume and grade. Patients are hyperglycemic for a mean period of 36–30 months before PDAC diagnosis; this information might be incorporated in strategies for early detection.

Keywords: early detection, biomarker, sojourn time, time course study

Background

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) carries a dismal prognosis. Currently the third leading cause of cancer death in the United States, by 2020 PDAC is expected to cause more deaths than breast, colon and prostate cancers1. To address this issue the US Congress passed the Recalcitrant Cancer Act and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) proposed priorities for PDAC research2, foremost among them being the study of the relationship between diabetes and PDAC and developing screening strategies for PDAC2. As 85% of PDAC are un-resectable at diagnosis, early detection of resectable PDAC provides the best hope for prolonging survival3. New-onset diabetes is a harbinger of pancreatic cancer4 and subjects with new-onset diabetes have a ~8-fold higher risk of having PDAC5.

In PDAC, which is rapidly fatal after diagnosis, it is important to know how long invasive cancer has been present prior to diagnosis. The progression of PDAC before its clinical diagnosis starts with first evidence of detectable cancer, progresses through an asymptomatic but potentially detectable phase (lead time), and terminates at clinical cancer diagnosis6. Knowing the duration of this pre-diagnostic stage of PDAC will help determine if early detection is even feasible.

For cancers with a clinical screening program, the duration of this pre-diagnostic stage has been estimated from time to development of interval cancer following a negative screening study, factoring in sensitivity of the screening test and the growth rate of cancer8–14. It is estimated that prostate cancer has a mean pre-diagnostic stage of 11–12 years7, breast cancer 3–4 years8,9, colon cancer 2–6 years10,11 and lung cancer 0.5–2.5 years12,13. As sporadic PDAC does not have an as-yet effective screening program, these approaches cannot be used to estimate its duration of pre-diagnostic stage.

We took a novel approach to estimate the duration of pre-diagnostic stage of sporadic PDAC by following the trail of hyperglycemia that precedes its clinical diagnosis. At PDAC diagnosis ~85% of subjects have hyperglycemia and 50% have diabetes, suggesting that elevation of glucose is a near universal phenomenon in PDAC14. This makes it a suitable marker to study the duration of pre-diagnostic stage, assuming that cancer is detectable at the onset of hyperglycemia, currently an unproven but hopeful premise. For this study we constructed a temporal glycemic profile of PDAC and matched general population controls to determine the duration of pre-diagnostic hyperglycemia.

The challenge with this approach is to show that the earliest glycemic signal is produced by invasive cancer. We postulated that the fading hyperglycemic signal with time observed in the temporal glycemic profile was caused by decreasing tumor volume. We determined if a threshold of tumor volume is required to cause hyperglycemia. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a cross-sectional glycemic profile in a large cohort of resected PDAC and compared mean FBG at each doubling of tumor volume with that of matched controls. We validated some of our key findings in a cohort of resected PDAC who also had longitudinal FBG data. Based on our studies we conclude that the mean hyperglycemia-defined duration of pre-diagnostic stage of PDAC is 30–36 months, providing a sufficient window-of-opportunity for early detection of PDAC.

Patients and Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Foundation Institutional Review Board and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Cohorts assembled

We compared glycemic profiles of PDAC vs. age- and gender-matched controls in three cohorts: a temporal fasting blood glucose (FBG) profile for 60 months prior to PDAC diagnosis (index date) (Cohort A); a cross-sectional FBG profile of resected PDAC stratified by tumor volume and grade (Cohort B); and a temporal FBG profile in resected PDAC with longitudinal FBG data (Cohort C). Supplementary Figure 1 is a flowchart describing identification of PDAC cases in the various cohorts.

Cohort A: Population-based temporal glycemic profile of all PDAC

Population-based epidemiologic studies can be conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota, because medical care is effectively restricted to 2 major health care providers serving almost the entire population15. Their health records are linked by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), funded by the NIH since 196616. We used diagnostic index codes to identify all PDAC cases in Olmsted County between 2000 and 2015 (n=400), manually reviewed their medical charts to include only those (n=219) with a definite (confirmed by histopathology, n=190) or probable diagnosis of PDAC (pancreatic mass with elevated CA19-9 or obstructive jaundice, n=29). For each PDAC we selected 2 age- (same birth year) and gender-matched Olmsted County residents as controls who were seen at the Mayo Clinic in the same calendar month as the matched case’s date of PDAC diagnosis (index date) (n=440). Control selection was blinded to glycemic status. To construct the temporal glycemic profile we electronically retrieved all outpatient fasting blood glucose (FBG) values at and up to 60 months prior to index date for cases and controls, grouped into 6-month time periods.

Cohort B: Cross-sectional glycemic profile of resected PDAC

To correlate tumor volume with FBG we constructed the glycemic profile of a cohort of resected PDAC. From Mayo Clinic’s prospective tumor registry we identified all resected PDAC between 1/1//1976 and 1/1/2017. We included all tumors with a diameter of <30 mm (n=386) and sub-sampled a representative cohort of 190 patients from among the rest (n=874); we then excluded patients without reported tumor size or those who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy (n=50). All histopathological reports were manually reviewed to verify PDAC diagnosis, tumor size, grade and lymph node (LN) positivity. The tumor slides were re-reviewed in 10% of resected PDAC by an expert pancreatic pathologist (T.C.S) to validate the reported pathologic grade (concordance 85%). Tumors were grouped by doubling tumor volumes starting at <0.5 cc (V1) through V7 (>16.0 cc). We abstracted all outpatient FBG values at the time of PDAC diagnosis and between 4 and 6 weeks after surgical resection. In addition, data on CA 19-9 (IU/L) levels at cancer diagnosis was noted. Vital status was noted from tumor registry and medical records.

For each case, we randomly identified 3 controls blinded to glycemic status and matched for gender and birth year who were seen in the clinic in the same month as the index date (n=1650). Of these, 1023 subjects (62%) had an outpatient FBG value and were included in the study; on average there were 2 controls with FBG per case at each tumor volume.

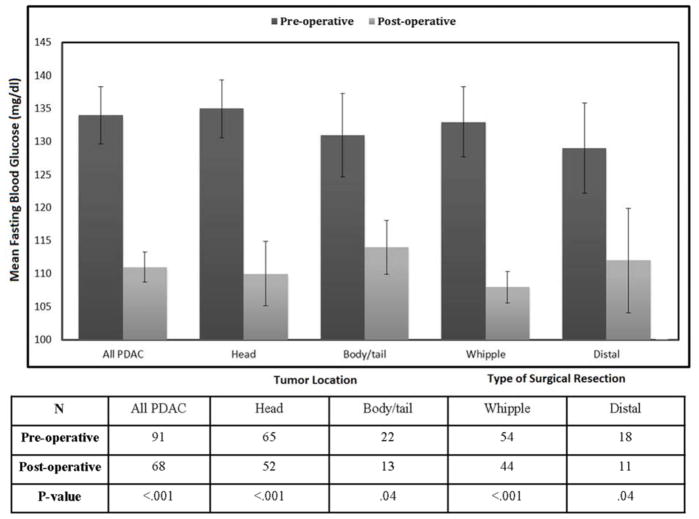

Cohort C: Population-based temporal glycemic profile of all resected PDAC

We constructed a population-based cohort of resected PDAC from a 27-county region of the recently expanded REP catchment area who also had longitudinal FBG data prior to PDAC diagnosis (n=103). Of these, 48 were from Olmsted County and were also included in cohort A. We used the Olmsted County population-based controls for comparison. Cohort C served as a validation cohort for key findings from Cohorts A and B. Pre- and post-operative FBGs were recorded in all subjects and compared to FBG of controls. Subset analyses were performed based on tumor location (head and body/tail) as well as by type of surgery (Whipple [pancreatico-duodenectomy] vs. distal pancreatectomy).

Calculating tumor volume

The most common method of reporting tumor size is by its largest diameter. This assumes that the tumor is spherical in shape and that growth occurs uniformly in all directions. We, however, observed that very few tumors (<10%) were spherical and most had 3 different reported dimensions. Therefore, we calculated tumor volume as for a scalene ellipsoid (4/3Π r1xr2xr3) factoring in all 3 tumor dimensions. For each category of an ellipsoid volume, there was a wide range of the largest tumor diameter (Supplementary Table 1).

Sensitivity analysis

Exclusion of subjects with diabetes at baseline

We compared the temporal glycemic profile of cases and controls after excluding subjects with a diagnosis of diabetes or with FBG of >126 mg/dl at baseline (60 to 54 months) in Cohort A and re-evaluated the temporal glycemic progression between cases and controls.

Resected vs. Un-resected PDAC

We compared the temporal glycemic profile of Olmsted County population-based controls with that of all resected PDAC subjects in Cohort C and all un-resected PDAC subjects in Cohort A. We further compared the temporal glycemic profile of Olmsted County population-based controls with that of PDAC subjects with large resected tumors (>16.0 cc), intermediate and small resected tumors (<16.0 cc) in Cohort C and all un-resected PDAC subjects in Cohort A.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using commercial software (JMP, version 10.0, SAS Institute Inc.). All the results are expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) as appropriate. The Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. The two-tailed t test was used to compare continuous variables. Polynomial regression analyses were used to model the observed mean FBG (± standard error of mean) in each time interval/volume category between cases and controls. A p value of ≤.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Cohort A: Temporal glycemic profile of population-based PDAC

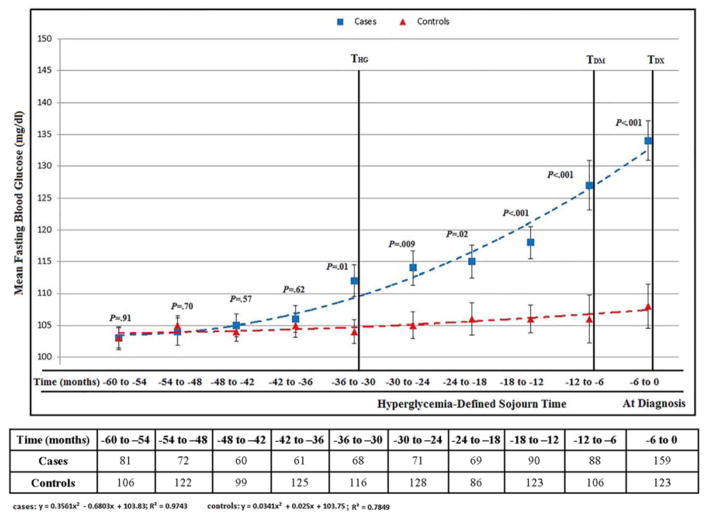

In Cohort A the baseline demographic and clinical profiles of cases and controls were comparable (Supplementary Table 2) with 159/219 (73%) of PDAC having FBG at diagnosis and an average of 3.5 (±2) measurements in previous 60 months. The mean FBG was similar in cases and controls in the 60 to 54, 54 to 48, 48 to 42 and 42 to 36-month intervals prior to index date (Supplementary Table 3). Relative hyperglycemia (mean FBG in cases higher than mean FBG in controls, p≤0.05) was seen starting 36 to 30 months prior to index date (THG) and progressively worsened in the subsequent time intervals until diagnosis (TDX). FBG in PDAC cohort peaked above diabetes level (≥126mg/dl) (TDM) 6 months prior to TDX (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort A: Temporal glycemic profile of population-based controls and pancreatic cancer up to 60 months before index date (see also supplementary table 3)

Abbreviations: THG, onset of hyperglycemia; TDM, onset of diabetes; TDX, cancer diagnosis

Cohort B: Cross-sectional glycemic profile of resected PDAC

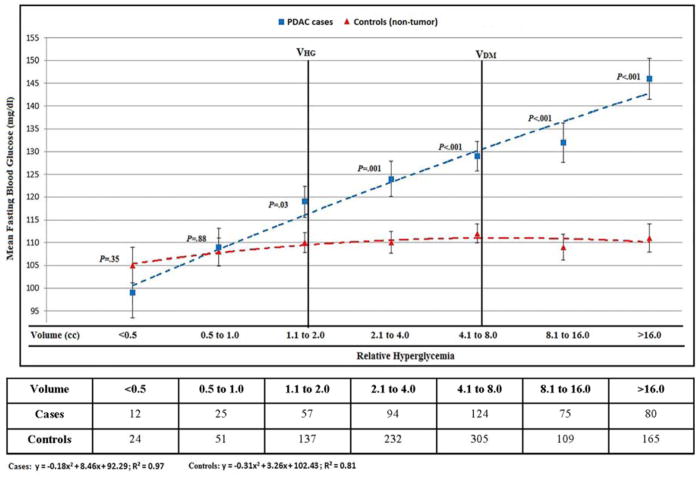

The details of demographic, clinical and pathologic features of resected PDAC in Cohort B are in Table 1. Of PDAC patients in Cohort B 466/526 (90%) had FBG values at TDX. The mean FBG was similar in cases and controls for V1 (<0.5 cc) and V2 (0.5–1.0 cc) tumor volumes. Relative hyperglycemia was first noted at V3 (1.1–2.0 cc) (VHG) and progressively worsened with subsequent tumor volume doublings (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4). The cohort mean FBG peaked above diabetes level (≥126mg/dl) at V5 (4.1 to 8.0 cc) tumor volume (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Cohort B: Profile of resected pancreatic cancer patients

| Characteristics | V1 (n=37) | V2 (n=67) | V3 (n=108) | V4 (n=136) | V5 (n=88) | V6 (n=90) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume groupings (cc) | <1.0 | 1.1 to 2.0 | 2.1 to 4.0 | 4.1 to 8.0 | 8.1 to 16.0 | >16.0 | |

| Longest dimension (mm), [Median (IQR)] | 14 (12–16) | 18 (15–20) | 22 (20–25) | 26 (25–28) | 34 (30–39) | 48 (42–59) | |

| Clinical characteristics | Age, y (mean ±SD) | 62 (±12.3) | 64 (±10.9) | 67 (±10.4) | 65 (±11.8) | 65 (±10.5) | 67 (±11.2) |

| Gender, male (%) | 19 (51) | 30 (45) | 58 (54) | 58 (43) | 51 (58) | 51 (57) | |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 | 26.9 | 26.9 | 26.2 | 26.1 | 26.2 | |

| Mean weight (kg) | 76 | 86 | 85 | 101 | 86 | 80 | |

| Tumor Differentiation (%) | Well/Moderate | 11 (32) | 26 (42) | 34 (32) | 38 (28) | 24 (27) | 19 (21) |

| Poor | 16 (47) | 31 (50) | 64 (60) | 78 (58) | 53 (60) | 58 (64) | |

| Undifferentiated | 7 (21) | 5 (8) | 8 (8) | 19 (14) | 11 (13) | 13 (14) | |

| Lymph Nodes + (%) | 11/34 (32) | 28/63 (44) | 56/106 (53) | 83/135 (61) | 57/88 (65) | 64/88 (73) | |

| CA19-9>50 IU/L (%) | 3/11 (27) | 9/34 (37) | 12/34 (35) | 27/48 (56) | 12/16 (75) | 25/32 (78) | |

| Diabetes | Overall (%) | 15 | 31 | 35 | 36 | 46 | 48 |

| Mean FBG (mg/dl) | 105 | 118 | 124 | 128 | 132 | 137 | |

| Survival | Median (months) | 29 | 27 | 24 | 21 | 19 | 15 |

| Range (months) | 4–316 | 1.7–276 | 0.5–215 | 0.8–281 | 0.5–170 | 2–158 | |

| Tumor location (%) | Head/neck | 32 (86%) | 56 (84%) | 96 (89%) | 116 (85%) | 73 (83%) | 60 (67%) |

| Body | 1 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 7 (6%) | 8 (6%) | 5 (6%) | 11 (12%) | |

| Tail | 1 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 8 (6%) | 7 (8%) | 19 (21%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (8%) | 6 (9%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (3%) | 3 (3%) | … | |

| Resection type (%) | Whipple | 3 (8%) | 7 (10%) | 10 (9%) | 10 (7%) | 16 (18%) | 30 (33%) |

| Distal | 18 (48%) | 46 (69%) | 73 (68%) | 86 (63%) | 63 (72%) | 44 (49%) | |

| Total | 4 (11%) | 1 (2%) | 9 (8%) | 18 (13%) | 6 (7%) | 7 (8%) | |

| Extended | 1 (3%) | 0 | 5 (5%) | 6 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (30%) | 13 (19%) | 11 (10%) | 11 (8%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (7%) | |

| Symptoms (%) | Abdominal pain | 12 (32%) | 31 (46%) | 46 (43%) | 75 (55%) | 53 (60%) | 52 (58%) |

| Back pain | 3 (8%) | 5 (7%) | 7 (6%) | 15 (11%) | 11 (12%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Jaundice | 28 (76%) | 48 (72%) | 77 (71%) | 87 (64%) | 61 (69%) | 47 (52%) | |

| Anorexia | 2 (5%) | 7 (10%) | 12 (11%) | 49 (36%) | 42 (48%) | 44 (49%) | |

| Appetite loss | 4 (11%) | 5 (7%) | 18 (17%) | 39 (29%) | 38 (43%) | 23 (26%) | |

| Weight loss | 17 (46%) | 34 (51%) | 63 (58%) | 79 (58%) | 56 (64%) | 57 (63%) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood glucose; IQR, inter-quartile range; SD, standard deviation

Figure 2.

Cohort B: Cross-sectional glycemic profile of controls (non-tumor bearing) and resected pancreatic cancer subjects stratified by tumor volume (see also supplementary table 4)

Abbreviations: VHG, volume associated with hyperglycemia; VDM, volume associated with diabetes; VDX, median volume at diagnosis

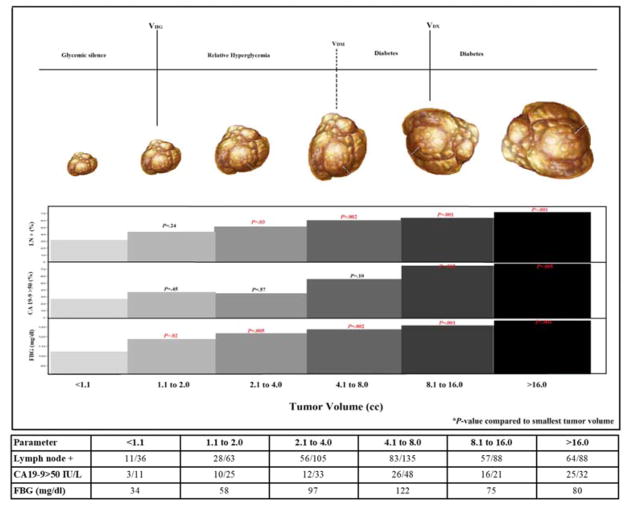

When compared to tumor volume not associated with hyperglycemia (V1; ≤1.0 cc) these features were first noted at following tumor volumes: relative hyperglycemia at V2 (1.1–2.0 cc) (105 vs. 118; p=.02), CA19-9 (>50 IU/L) at V5 (8.1–16.0 cc) (27% vs. 75%; p=.002) and LNs involvement at V3 (2.1–4.0 cc) (31% vs. 53%; p=.03) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Fasting blood glucose, CA19-9 and lymph node involvement with increasing tumor volume of pancreatic cancer

Abbreviations: VHG, volume associated with hyperglycemia; VDM, volume associated with diabetes; VDX, median volume at diagnosis

Cohort C: Temporal glycemic profile of population-based resected PDAC

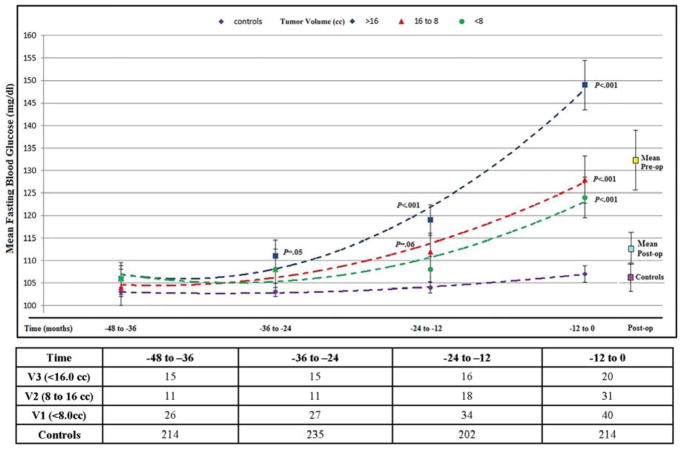

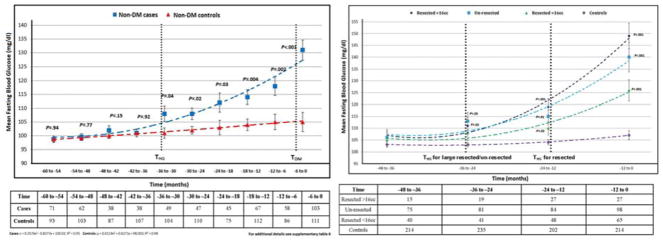

PDAC subjects in Cohort C had a mean age (years) of 67 (±11.8), 50% were women and had a median tumor volume of 11.5 cc (IQR, 5.4 to 17.5). Of PDAC patients in Cohort C 91/103 (88%) had FBG values at diagnosis with 83 (81%) having ≥3 measurements in previous years (mean 3.5 [±1.2]/subject). For PDAC cases with large tumor volume (>16.1 cc) mean FBG (mg/dl) similar to controls was noted at 48 to 36 month interval prior to index date with progressively worsening relative hyperglycemia in the 36 to 24, 24 to 12 and 12 to 0 months intervals prior to index date. For PDAC with medium tumor volumes (8.1 to 16.0 cc) mean FBG (mg/dl) similar to controls was noted in the 48 to 36 and 36 to 24 month intervals prior to index date with progressively worsening relative hyperglycemia in 24 to 12 and 12 to 0 month intervals prior to index date. For PDAC with small tumor volumes (<8.1cc) mean FBG (mg/dl) similar to controls was noted in 48 to 36, 36 to 24 and 24 to 12-month intervals prior to index date with relative hyperglycemia seen only in 12 to 0 month interval prior to index date (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 5). In PDAC subjects resolution of hyperglycemia was noted post-resection and was independent of tumor location or type of surgery (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 4.

Cohort C: Temporal glycemic profile of population-based controls and resected pancreatic cancer subjects stratified by tumor volume up to 48 months before index date (see also supplementary table 5)

Figure 5.

Pre- and post-operative fasting blood glucose in resected pancreatic cancer patients by location of tumor and type of surgical resection (see also supplementary table 6)

Cross-sectional glycemic profile of resected PDACs by tumor grade

Of the resected PDAC 300/526 (57%) were poorly differentiated, 152 (29%) were well/moderate and 63 (12%) were undifferentiated; 11 (2%) were of undetermined grade. The mean FBG of well to moderately differentiated tumors was lower than that of poorly differentiated tumors (118 vs. 134; p=.01). There was no significant difference in the average tumor volume (cc) of the well/moderate vs. poorly differentiated tumors (8.3 vs. 10.6; p=.09). The VHG of poorly differentiated tumors occurred at smaller tumor volumes (1.1 to 2.0 cc; mean 1.5 [±0.3]) in comparison to moderately differentiated tumors (4.1 to 8.0 cc; mean 5.8 [±1.1]).

Sensitivity analysis

Subjects with diabetes at baseline

The THG of the Cohort A after excluding subjects with baseline (60 to 54 months) FBG of ≥126 mg/dl or a diagnosis of diabetes was similar to that of the entire Cohort A, viz., 36-30 months (Figure 6A, Supplementary Table 7)

Figure 6.

A. Cohort A: Temporal glycemic profile of population-based controls and pancreatic cancer after excluding subjects with diabetes at baseline (60 to 54 months) (see also supplementary table 7). Figure 6.B: Temporal glycemic profile of population-based controls and large resected (>16.0 cc), intermediate and small resected (<16.0 cc) and un-resected pancreatic cancer subjects up to 48 months before index date (see also supplementary table 8)

Abbreviations: THG, onset of hyperglycemia; TDM, onset of diabetes

Resected vs. un-resected

Compared to controls, the THG of resected PDAC subjects was similar to that of un-resected PDAC subjects (Supplementary Figure 2). Compared to controls, the glycemic profile of un-resected tumors and large (>16.0 cc) resected tumors was similar, with both groups having THG at 36 to 24 months prior to index date compared to intermediate and small (<16.0 cc) resected tumors, THG occurred at 24 to 12 months prior to index date (Figure 6B, Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

The goal of our study was to estimate the mean duration of pre-diagnostic progression of sporadic PDAC, an important but unknown parameter that is key to developing early detection strategies for PDAC. For this we took advantage of the fact that the cancer causes hyperglycemia that predates its diagnosis. By constructing glycemic profiles of multiple large longitudinal and cross-sectional PDAC cohorts, both population- and clinic-based, and matched controls, we have made multiple novel observations in addition to confirming many previous observations. We show that the hyperglycemic signal in PDAC is strongest at diagnosis and fades over the preceding 30–36 months, is associated with tumor volume threshold of >1.1 cc, and is caused by invasive cancer. Based on these data we estimate the mean hyperglycemia-defined duration of pre-diagnostic progression of PDAC to be 30–36 months.

Previous studies, by others and us, have shown that new-onset diabetes is a harbinger of PDAC 17. To study this phenomenon further we constructed the first population-based glycemic profile of PDAC, a 60-month temporal FBG profile of all PDAC diagnosed in Olmsted County over a 16-year period and matched controls. There were mean of 3.5 FBG measurements for each subject in the 5-year study period. This density of FBG data allowed us to analyze it by 6-month intervals. The temporal glycemic profile shows that hyperglycemia first occurs 36–30 months before PDAC diagnosis, rapidly progresses with decreasing lead time and crosses the diabetes threshold 12–6 months prior to cancer diagnosis.

To determine if there is tumor volume threshold (VHG) associated with relative hyperglycemia we constructed a cross-sectional glycemic profile in a cohort of resected PDAC and matched controls. This large cohort had strong representation of tumors in every volume category, from very small (<1 cc) to very large (>16 cc). We observed that the hyperglycemic signal was strongest in larger tumors and faded with decreasing tumor volume. Importantly, we noted mean FBG (mg/dl) similar to age- and gender-matched controls in invasive PDAC <1 cc in volume and after PDAC resection, confirming that invasive PDAC with a certain volume threshold is the cause of hyperglycemia. Interestingly, we did not note a difference between the pre- and post-resected mean FBG levels based on location of tumor or type of surgical resection (Figure 5).

PDAC Cohort C allowed us to study the temporal glycemic profile of tumors of known volume at diagnosis. In this cohort, we could show that larger resected tumors have longer hyperglycemia-defined sojourn time compared to smaller tumors as was seen in cross-sectional profile of resected PDAC. Both temporal and cross-sectional glycemic profiles showed an average of 3 years between T/VHG and an average volume of PDAC at diagnosis (~11.5 cc). Thus, both temporal and cross-sectional glycemic profiles suggest a 3-year hyperglycemia-defined duration of pre-diagnostic stage.

Our data show that glycemic profile of un-resected tumors is similar to that of large (≥16 cc) resected tumors, with both groups having similar THG at 36 to 24 months prior to cancer diagnosis (Figure 6b). The profile of un-resected tumors is intermediate between that of large resected (≥16 cc) and medium-sized (8–16 cc) resected tumors, which have a THG at 24 to 12 months (Figure 6B). Un-resected tumors, like resected ones, are likely a mixture of tumors of different volumes, but collectively have a profile similar to that of the largest resected tumors. It is unclear if and how much metastases contribute to rising FBG in PDAC. It is also unclear if increasing hyperglycemia causes increasing tumor volume and so a self-perpetuating cycle is established. However, whether hyperglycemia is the cause or effect of increasing tumor volume is difficult to prove, at least in humans.

Clinico-pathological 18, transcriptomic 19, 20 and molecular 21 data show tumor heterogeneity. We see this in the hyperglycemic profiles as well, with poorly differentiated tumors having smaller VHG and higher FBG at diagnosis compared to moderate/well differentiated tumors. This novel observation likely reflects metabolic reprogramming in poorly differentiated tumors to cope with a harsh microenvironment 22, 23. The mechanism(s) of PDAC-induced hyperglycemia still remains unknown, though others 24, 25 and we 17, 26 have postulated possible mediators of the paraneoplastic DM in PDAC. The current efforts to find potential mediator(s) of PDAC-induced diabetes have been focused on PDAC cells. However, the fact that increasing volume of a predominantly desmoplastic tumor causes increasing hyperglycemia raises the possibility that the mediators of hyperglycemia may be produced by the stroma or cancer associated fibroblasts.

From an early detection stand point it is clear from our data that distinguishing PDAC-induced hyperglycemia from pre-diabetes of type 2 DM could lead to early detection of PDAC. However, this will require enrichment of the pre-diabetes cohort for PDAC as nearly half the population at the age of 60 has elevated FBG 27. Efforts are underway to identify blood-based biomarkers of PDAC 28, 29. Efforts to develop algorithms that can distinguish new-onset DM due to PDAC from new-onset type 2 DM 30 are also ongoing. If these algorithms could be extended to subjects with new-onset rapidly worsening prediabetes, it could potentially detect PDAC even earlier. This is supported by our findings that tumor volume (cc) at VHG (1.1 to 2.0) was markedly lower than at VDM (4.1 to 8.0).

An important finding of our study is the estimate of smallest tumor volume that is associated with hyperglycemia and with diabetes. At these volumes, the range of largest tumor diameter of these irregularly shaped tumors is quite broad (Supplementary Table 1), but provides hope that such tumors can be detected by endoscopic ultrasound or a novel imaging modality. Between the volume of smallest tumor associated with hyperglycemia and typical volume of cancer at diagnosis we estimate that the tumor doubles in volume 4–5 times. This provides ample opportunity for early diagnosis of PDAC.

Our study has some limitations. It is a retrospective study based on review of medical records; however such a study would be very difficult to perform prospectively. The glycemic profiles constructed are that of the cohort; individual glycemic profiles vary. Hyperglycemia-defined duration of pre-diagnostic progression is applicable only to tumors that develop hyperglycemia; however only 10% of the subjects with sporadic PDAC have normal FBG at diagnosis 14. Thus, this estimated duration of pre-diagnostic progression is relevant to majority of the sporadic PDAC patients.

In summary, our study shows that hyperglycemia is a marker of invasive PDAC and allows estimation of its preclinical dwell time. Hyperglycemia-defined duration of pre-diagnostic stage of 36-30 months is long enough to allow opportunity for early diagnosis of PDAC at earlier stages.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Longest tumor dimension (Median and Range) for various volume categories

Supplementary Table 2. Cohort A: Baseline characteristics of Olmsted County patients (cases and controls) during the period of glycemic silence (60 to 36 months prior to index date)

Supplementary Table 3. Cohort A: Mean FBG at various time intervals in PDAC and Controls (Figure 1)

Supplementary Table 4. Cohort B: Mean FBG at various tumor volumes of resected pancreatic cancer and Controls (Figure 2)

Supplementary Table 5. Cohort C: Mean FBG at various time intervals in resected pancreatic cancer stratified by tumor volume and corresponding Controls (Figure 4)

Supplementary Table 6. Pre- and post-operative mean fasting blood glucose (FBG) in population-based resected pancreatic cancer cases by tumor location and type of surgical resection (Figure 5)

Supplementary Table 7. Temporal glycemic profile of population-based controls and pancreatic cancer after excluding subjects with diabetes at baseline (60 to 54 months) in Cohort A (Figure 6A)

Supplementary Table 8. Temporal glycemic profile of population-based controls and large resected (>16.0 cc), intermediate and small resected (<16.0 cc) and un-resected pancreatic cancer subjects up to 48 months before index date (Figure 6B)

Acknowledgments

Grant support

This work was supported by the NIH U01 Consortium for Study of Chronic Pancreatitis, Diabetes and Pancreatic cancer (CPDPC) (Chari and Topazian), Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (Chari), Kenner Family Research Fund (Chari), Prokopanko Gift to Mayo Foundation (Sharma and Chari). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any other funding source.

We gratefully acknowledge the critical review of the manuscript by Dr. David Ahlquist, Mayo Clinic Rochester and Dr. Rahul Suresh, University of Texas Medical Branch

Abbreviations

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- FBG

fasting blood glucose

- HG

hyperglycemia

- PDAC

pancreatic cancer

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Study concept and design: STC and AS

Acquisition of data: AS

Analysis and interpretation of data: AS and STC

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scientific Framework for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) National Cancer Institute; 2014. [accessed October 22, 2017]. Available from: http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/ctac/workgroup/pc/PDACframework.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chari ST, Kelly K, Hollingsworth MA, et al. Early detection of sporadic pancreatic cancer: summative review. Pancreas. 2015;44:693–712. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pannala R, Basu A, Petersen GM, et al. New-onset diabetes: a potential clue to the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:88–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chari ST, Leibson CL, Rabe KG, et al. Probability of pancreatic cancer following diabetes: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:504–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draisma G, van Rosmalen J. A note on the catch-up time method for estimating lead or sojourn time in prostate cancer screening. Stat Med. 2013;32:3332–41. doi: 10.1002/sim.5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pashayan N, Duffy SW, Pharoah P, et al. Mean sojourn time, overdiagnosis, and reduction in advanced stage prostate cancer due to screening with PSA: implications of sojourn time on screening. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1198–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy SW, Chen HH, Tabar L, et al. Sojourn time, sensitivity and positive predictive value of mammography screening for breast cancer in women aged 40–49. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:1139–45. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.6.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Brock G, Wu D. Estimating key parameters in periodic breast cancer screening-application to the Canadian National Breast Screening Study data. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010;34:429–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu D, Erwin D, Rosner GL. Estimating key parameters in FOBT screening for colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes & Control. 2009;20:41–46. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9215-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng W, Rutter CM. Estimated mean sojourn time associated with hemoccult SENSA for detection of proximal and distal colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2012;21:1722–1730. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu D, Erwin D, Rosner GL. Sojourn time and lead time projection in lung cancer screening. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:322–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chien CR, Chen TH. Mean sojourn time and effectiveness of mortality reduction for lung cancer screening with computed tomography. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2594–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pannala R, Leirness JB, Bamlet WR, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:981–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, et al. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sah RP, Nagpal SJ, Mukhopadhyay D, et al. New insights into pancreatic cancer-induced paraneoplastic diabetes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:423–33. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:567–79. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus R, Maitra A, Roszik J. Recent advances in genomic profiling of adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas. J Pathol. 2017;243:271–272. doi: 10.1002/path.4959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akakura N, Kobayashi M, Horiuchi I, et al. Constitutive expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha renders pancreatic cancer cells resistant to apoptosis induced by hypoxia and nutrient deprivation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6548–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Zhao S, Nakada K, et al. Dominant-negative hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha reduces tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer cells through the suppression of glucose metabolism. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1283–91. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63924-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Permert J, Larsson J, Westermark GT, et al. Islet amyloid polypeptide in patients with pancreatic cancer and diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:313–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402033300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding X, Flatt PR, Permert J, et al. Pancreatic cancer cells selectively stimulate islet beta cells to secrete amylin. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:130–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aggarwal G, Ramachandran V, Javeed N, et al. Adrenomedullin is up-regulated in patients with pancreatic cancer and causes insulin resistance in beta cells and mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1510–1517. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Control CfD, Prevention. National diabetes statistics report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang H, Dong X, Kang MX, et al. Novel blood biomarkers of pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus identified by peripheral blood-based gene expression profiles. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1661–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J, Bamlet WR, Oberg AL, et al. Detection of early pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with thrombospondin-2 and CA19-9 blood markers. Sci Transl Med. 2017:9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah5583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boursi B, Finkelman B, Giantonio BJ, et al. A Clinical Prediction Model to Assess Risk for Pancreatic Cancer Among Patients With New-Onset Diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:840–850. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Longest tumor dimension (Median and Range) for various volume categories

Supplementary Table 2. Cohort A: Baseline characteristics of Olmsted County patients (cases and controls) during the period of glycemic silence (60 to 36 months prior to index date)

Supplementary Table 3. Cohort A: Mean FBG at various time intervals in PDAC and Controls (Figure 1)

Supplementary Table 4. Cohort B: Mean FBG at various tumor volumes of resected pancreatic cancer and Controls (Figure 2)

Supplementary Table 5. Cohort C: Mean FBG at various time intervals in resected pancreatic cancer stratified by tumor volume and corresponding Controls (Figure 4)

Supplementary Table 6. Pre- and post-operative mean fasting blood glucose (FBG) in population-based resected pancreatic cancer cases by tumor location and type of surgical resection (Figure 5)

Supplementary Table 7. Temporal glycemic profile of population-based controls and pancreatic cancer after excluding subjects with diabetes at baseline (60 to 54 months) in Cohort A (Figure 6A)

Supplementary Table 8. Temporal glycemic profile of population-based controls and large resected (>16.0 cc), intermediate and small resected (<16.0 cc) and un-resected pancreatic cancer subjects up to 48 months before index date (Figure 6B)