Abstract

Extracellular adenosine is a danger/injury signal that initiates protective physiology, such as hypothermia. Adenosine has been shown to trigger hypothermia via agonism at A1 and A3 adenosine receptors (A1AR, A3AR). Here, we find that adenosine continues to elicit hypothermia in mice null for A1AR and A3AR and investigated the effect of agonism at A2AAR or A2BAR. The poorly brain penetrant A2AAR agonists CGS-21680 and PSB-0777 caused hypothermia, which was not seen in mice lacking A2AAR. MRS7352, a likely non-brain penetrant A2AAR antagonist, inhibited PSB-0777 hypothermia. While vasodilation is probably a contributory mechanism, A2AAR agonism also caused hypometabolism, indicating that vasodilation is not the sole mechanism. The A2BAR agonist BAY60-6583 elicited hypothermia, which was lost in mice null for A2BAR. Low intracerebroventricular doses of BAY60-6583 also caused hypothermia, indicating a brain site of action, with neuronal activation in the preoptic area and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Thus, agonism at any one of the canonical adenosine receptors, A1AR, A2AAR, A2BAR, or A3AR, can cause hypothermia. This four-fold redundancy in adenosine-mediated initiation of hypothermia may reflect the centrality of hypothermia as a protective response.

Keywords: hypothermia, adenosine, A2AAR, A2BAR, preoptic area, paraventricular hypothalamus

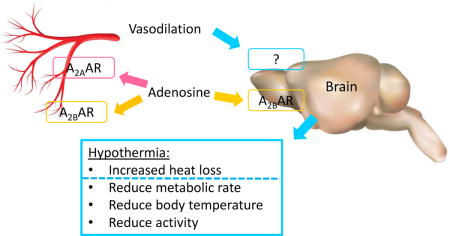

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Maintenance of a warm, regulated core body temperature (Tb) is a defining feature of mammals and birds. In homeotherms, hypothermia can be caused by excessive cold exposure, severe injury or illness, and many drugs. In large mammals, such as adult humans, hypothermia is relatively difficult to achieve. In contrast, small mammals, such as mice, are at risk of hypothermia and expend relatively massive amounts of energy to maintain their Tb, a process in which brown fat has a large role. The high energetic cost of defending Tb means that small mammals have evolved strategies for using Tb reduction to conserve fuel. For example, with cold exposure or fasting, mice let their Tb fall slightly (~1°C). Mice can also enter torpor, during which Tb can fall >10°C, producing huge energetic savings (Gavrilova et al., 1999; Geiser, 2004; Hudson and Scott, 1979; Melvin and Andrews, 2009).

Hypothermia is observed with severe injury (Shafi et al., 2005) and sepsis (Fonseca et al., 2016). It is unknown if the poor prognosis associated with hypothermia is because hypothermia is a marker of clinical severity or if the hypothermia represents a physiologic response to the dire situation (Fonseca et al., 2016). Clinically, therapeutic hypothermia is used after insults such as neonatal hypoxic injury (Azzopardi et al., 2014) and cardiac arrest (Callaway et al., 2015), and prophylactically during certain types of hypoperfusion surgery (Yan et al., 2013). Therapeutic hypothermia is induced by cooling, sometimes with pharmacologic agents to block shivering. Drugs that induce hypothermia through reduction of the central Tb balance point could minimize counterregulatory mechanisms such as shivering and provide clinical benefit.

Extracellular adenosine is one of the body’s danger signals, an indicator of tissue damage or metabolic stress (Borea et al., 2016). Adenosine acts at four G protein-coupled receptors: A1AR, A2AAR, A2BAR, and A3AR. A1AR and A3AR are typically coupled to Gi, while A2AAR and A2BAR are usually coupled to Gs or Gq. Adenosine has many actions that dampen immune and inflammatory responses, one of which is causing hypothermia (Bennet and Drury, 1931). The best studied mechanism of adenosine-induced hypothermia is via agonism of brain A1AR, with proposed sites of action being the anterior hypothalamus and the nucleus of the solitary tract (Anderson et al., 1994; Carlin et al., 2017; Johansson et al., 2001; Muzzi et al., 2013; Shintani et al., 2005; Tupone et al., 2013). However, mouse genetic and pharmacologic evidence suggested that adenosine can cause hypothermia via other mechanisms (Yang et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2010). Hypothermia via A3AR is caused by agonism of peripheral mast cell A3AR, causing histamine release, which produces hypothermia via central histamine H1 receptors (Carlin et al., 2016). Since A1AR agonists must penetrate the brain to produce hypothermia, some compounds used as A1AR agonists may be causing hypothermia via peripheral mast cell A3AR (Carlin et al., 2017).

There is limited information on the role of A2AAR and A2BAR in hypothermia. The A2AAR agonist CGS-21680 produced mild hypothermia with a high i.c.v. dose (Anderson et al., 1994) or with peripheral dosing (Eisner et al., 2017). These effects were smaller than those seen with agonism at other adenosine receptors and were not investigated mechanistically. Intraarterial CGS-21680 caused hypotension in wild type but not Adora2a−/− mice, which may have been accompanied by hypothermia, but Tb was not measured (Ledent et al., 1997). In contrast, the A2AAR agonist PSB-0777 increased energy expenditure by stimulation of brown adipose tissue; effects on Tb were not reported (Gnad et al., 2014). No role for A2BAR in hypothermia has been identified (Fredholm et al., 2011).

Here we explored whether agonism at A1AR and A3AR completely accounts for the hypothermia potential of adenosine, or if A2AAR and A2BAR can also contribute. We find that agonism of either A2AAR or A2BAR does cause hypothermia, and investigate the pharmacology and mechanisms.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Male C57BL/6J and KitW−sh/W−sh (JAX #012861) (Grimbaldeston et al., 2005; Nigrovic et al., 2008) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Adora1−/− (Sun et al., 2001), Adora3−/− (Salvatore et al., 2000), and Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice were obtained and genotyped as reported (Carlin et al., 2017). Adora2a−/− mice (Chen et al., 1999) on a mixed background were obtained from Dr. Dorian McGavern and genotyped as described (JAX #010685). Adora2b−/− mice (Hua et al., 2007) on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from Dr. Stephen Tilley and genotyped as described (JAX #022499). Mice were singly housed at ∼22°C with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 am). Chow (NIH-07, Envigo Inc, Madison, WI) and water were available ad libitum. Drugs were typically dosed at 10:00 am. Mice were studied ≥7 days after any operation or prior treatment. Reuse of mice tends to reduce physical activity levels, presumably due to acclimatization. No specific effort was made to acclimatize mice to handling in individual experiments. Studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

2.2. Drugs

MRS7352 (4-((4-(3-(5-amino-2-(furan-2-yl)-7H-pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidin-7-yl)propyl)phenoxy)methyl)benzenesulfonate triethylammonium salt) was synthesized and purified by HPLC as described (Duroux et al., 2017). The following compounds (vehicle) were purchased from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN): CGS-21680 (15% DMSO/15% KolliphorEL/70% saline for i.p.; 5% DMSO/95% PBS neutralized with one equivalent of NaOH for i.c.v.); PSB-0777 (saline); BAY60-6583 (25% PEG); SCH442416 (15% DMSO/15% KolliphorEL/70% saline). Adenosine (10% DMSO in water) was obtained from Sigma. APEC (2-[[2-[4-[2-(2-aminoethyl)-aminocarbonyl]ethyl]phenyl]ethylamino]-5′-N-ethyl-carboxamidoadenosine; water) was obtained through NIMH Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply Program, http://nimh-repository.rti.org/. Regadenoson was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Screening of PSB-0777, SCH442416, BAY60-6583, and CGS-21680 for off target activities at 45 human receptors, channels, and transporters with radioligand binding assays was performed by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP) directed by Bryan L. Roth MD, PhD at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

2.3. Adenosine receptor binding affinities

Binding affinity for mouse A1AR, A2AAR, and A3ARs was measured as described (Kreckler et al., 2006) using membranes from human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells stably expressing individual recombinant mouse adenosine receptors and using the agonists [125I]N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-methyluronamide ([125I]AB-MECA; A1AR and A3AR) and [3H]CGS-21680 (A2AAR) as radioligands. Nonspecific binding was defined using 100 μM adenosine-5′N-ethylcarboxamide (NECA). Ki values were obtained using the Cheng-Prusoff equation from IC50 values calculated by non-linear regression analysis of specific binding data using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA).

2.4. Thermal physiology phenotyping

Implantation (coordinates relative to bregma: −0.34 mm anterior, 1.0 mm lateral, and +1.7 mm ventral) and use of chronic intracerebroventricular cannulas are described in (Carlin et al., 2017), as are the following procedures. Continuous telemetric monitoring of Tb and activity were performed using G2 E-mitters (Starr Life Sciences, Oakmont, PA) implanted intraperitoneally. Average Tb response was calculated using 0 to 60 min from agonist dosing and activity from 10 to 60 min. Inhibitors were dosed 20–25 min before agonists. Indirect calorimetry was performed using a 12-chamber CLAMS (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH).

2.5. Drug-induced neuronal activation

Sixty min after i.c.v. infusion, mice were euthanized with 7% chloral hydrate and perfused with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Brains were post fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C overnight. Coronal brain sections (40 μm) were cut, stored at 4°C for up to one week in PBS containing 0.02% sodium azide, washed in 0.1 M PBS, preincubated in blocking buffer (PBS + 0.2 % triton X-100 + 10% normal horse serum (NHS)) for 2 h at room temperature, and incubated with antibody to Fos (1:2000, Cell Signaling, #5348) in 2% NHS blocking buffer for 48 h at 4°C. After washing in PBS, tissue was incubated for 4 h with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:500 in PBS + 2% NHS blocking buffer, ThermoFisher Scientific #A31556). Fos was visualized by fluorescence microscopy with Olyvia software (Olympus Life Sciences). A blinded individual counted the Fos-positive neurons using Image J software (NIH). Display images were adjusted for brightness and contrast. Brain anatomy was defined using (Franklin and Paxinos, 2007).

Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Significance (two-tailed p < 0.05) was determined by t-test or ANOVA followed by post hoc Holm-Sidak multiple comparison tests.

3. Results

3.1 Adenosine Causes Hypothermia via Mechanisms Independent of A1AR and A3AR Receptors

To determine if there are mechanisms in addition to A1AR and A3AR by which adenosine causes hypothermia, we studied Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice, which lack both of these receptors. Handling for dosing with vehicle increased Tb and activity. Treatment with a relatively modest adenosine dose (100 mg/kg, i.p. (Eisner et al., 2017)) produced robust hypothermia in Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice, approaching that seen in C57BL/6J controls (Fig. 1). Thus, adenosine can cause hypothermia independent of A1AR and A3AR.

Fig. 1. Adenosine-mediated hypothermia remains intact in Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice.

(A,B) Tb and activity response to adenosine (ADO, 100 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle (Veh) in C57BL/6J (WT) and Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice. (C,D) Average Tb (0–60 min) and total physical activity (10–60 min). Data are mean ± SEM, n = 5–6/group in a crossover design; ***p < 0.001 vs vehicle within genotype.

3.2 Agonism at A2AAR causes hypothermia

We used CGS-21680, a modestly selective A2AAR agonist (Table 1), to test if A2AAR activation could produce hypothermia. CGS-21680 (0.01–1 mg/kg, i.p.) caused dose-dependent hypothermia and hypoactivity (Fig. 2A–C). CGS-21680 is only ~5-fold selective for A2AAR over A3AR (Table 1); therefore, we tested its specificity using mice lacking A2AAR. Treatment with CGS-21680 did not cause hypothermia in Adora2a−/− mice (Fig. 3A-C). In contrast, CGS-21680 hypothermia was intact in Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice (Fig. 3D-F). Adora2a is expressed in mast cells, but KitW−sh/W−sh mice, which lack mast cells, showed a hypothermic response to CGS-21680 (Fig. 3G-I). Screening of CGS-21680 for off-target activities detected none at <10 μM (see 2.2). Taken together, these data suggest that the hypothermic effects of CGS-21680 (at ≤1 mg/kg, i.p.) are via agonism at A2AAR, with little or no contribution from A1AR, A3AR, or mast cells.

Table 1.

Binding affinity of adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists used in this study.

| mouse Ki, nM (or % inhibition at 10 μM)*

|

rat Ki, nM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonists | A1AR | A2AAR | A2BAR | A3AR | A1AR | A1AR rat: mouse ratio | LogPS** or brain penetrant |

| CGS-21680 | 193a | 10a | >10,000b | 48a | 16c | 0.083 | nod |

| regadenoson | 7.75 ± 0.05e | 77.2 ± 6.3e | >100,000 (h)f | 7 ± 2%e | >16,000 (h)f | −4.37** | |

| PSB-0777 | 18.4 ± 1.1e | 193 ± 28e | >10,000 (h)g | 26 ± 1%e | ≥10,000g | >500 | nog |

| APEC | 4.17 ± 0.15e | 3.57 ± 0.22e | inactive (r)h | 55.1 ± 4.3e | 400i | 95 | yesd |

| BAY60-6583 | 351*** b | >10,000b | 136*** b | 3920*** b | 514b | 1.5 | −2.77** |

| Antagonists | |||||||

| SCH442416 | 765a | 1.3a | >10,000 (h)j | >10,000a | 1815j | 2.4 | yesj |

| MRS7352 | 21 ± 4%k | 64.1 ± 5.3k | 4 ± 1%k | −3.89** | |||

Data are for mouse, except if denoted (r) rat or (h) human.

The logPS is the blood-brain permeability-surface area product, calculated using http://bleoberis.bioc.cam.ac.uk/pkcsm/prediction. A logPS >-2 is considered penetrating, while logPS < −3 is non-penetrating (Pires et al., 2015).

BAY60-6583 may be an antagonist at A1 and A3AR and a partial agonist at A2BAR.

Superscripts indicate data source. SEM s are included for experimental results.

Current results

Fig. 2. Systemic CGS-21680 administration causes hypothermia and decreases physical activity.

(A) Tb response to the indicated i.p. CGS-21680 doses in C57BL/6J mice. (B,C) Effect of CGS-21680 on average Tb (0–60 min) and physical activity (10–60 min). Data are mean ± SEM, n = 3-7/group; **p<0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs vehicle.

Fig. 3. Systemic CGS-21680 causes hypothermia through A2AAR, not involving A1AR, A3AR, or mast cells.

(A-C) Tb and activity response to CGS-21680 (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle in C57BL/6J (WT) and Adora2a−/− mice. (D-F) Tb and activity response to CGS-21680 (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle in C57BL/6J (WT) and Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice. (G-I) Tb and activity response to CGS-21680 (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle in C57BL/6J (WT) and KitW−sh/W−sh mice. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 3–7/group; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs vehicle within genotype, *p < 0.05 or ***p =0.001 vs vehicle.

Given the modest adenosine receptor selectivity of CGS-21680, we examined the binding affinities of other commonly used A2AAR agonists on mouse receptors. In humans, regadenoson is used as a selective A2AAR agonist (Gao et al., 2001). However, in mouse it is not selective, binding to A1AR 10-fold more tightly than to A2AAR (Table 1), and we did not study it further. PSB-0777 is a selective A2AAR agonist in rat (El-Tayeb et al., 2011) and had few off-target activities, binding only human β1 (Ki 4.4 μM) and β3 (Ki 3.3 μM) adrenergic receptors. However, PSB-0777 bound mouse A1AR ≥1000-fold better than rat A1AR (Table 1), so in mouse PSB-0777 is a better ligand for A1AR than for A2AAR. Despite this lack of binding selectivity, in vivo, PSB-0777 caused dose-dependent hypothermia and hypoactivity (Fig. S1A-C) that was abolished in Adora2a−/− mice (Fig. S1D-F). This effective selectivity of PSB-0777 for A2AAR in causing hypothermia may be due to its poor CNS penetration (El-Tayeb et al., 2011), which precludes PSB-0777 from reaching the brain A1AR that trigger hypothermia. These data demonstrate that the hypothermic effects of PSB-0777 (at ≤3 mg/kg, i.p.) in mice occur via agonism at peripheral A2AAR.

APEC is readily brain penetrant, unlike CGS-21680 (Nikodijevic et al., 1990) and PSB-0777. APEC binds mouse A2AAR at 3.6 nM, but also binds mouse A1AR with high affinity (4.2 nM in mouse vs 400 nM in rat) (Table 1). Low peripheral doses of APEC caused hypothermia, blunting the handling hyperthermia at 1.7 μg/kg i.p. and producing robust hypothermia and hypoactivity at 50 μg/kg (Fig. S1G-I). APEC-induced hypothermia was attenuated in both Adora2a−/− and Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice but fully intact in Adora2b−/− mice (Fig. S1J-L). To specifically test if central A2AAR activation can induce hypothermia, we dosed CGS-21680 i.c.v. No hypothermia was observed with 0.01 mg/kg, while 0.1 mg/kg i.c.v. produced similar hypothermia to 0.25 mg/kg i.p. (Fig. 4). These data are consistent with CGS-21680, PSB-0777, and APEC each causing hypothermia via peripheral but not central A2AAR, with APEC but not CGS-21680 or PSB-0777 also causing hypothermia via central A1AR.

Figure 4. No hypothermic response to intracerebroventricular CGS-21680.

(A–C) Tb and activity response to i.c.v. CGS-21680 (0.01 or 0.1 mg/kg) or vehicle in C57BL/6J mice. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 4–6/group in a crossover design.

3.3 Effect of A2AAR antagonist on hypothermia

Treatment with the selective, brain-penetrant A2AAR antagonists SCH442416 (3 mg/kg, i.p.) or preladenant (1 mg/kg, i.p.) caused increased locomotor activity (data not shown), probably from activation of the A2AAR on striatal neurons. The increased activity likely explains (Lateef et al., 2014) the observed increase in Tb (data not shown). Screening SCH442416 for off-target activities by the PDSP detected binding to the human 5HT2B receptor (Ki 0.91 μM), M3 acetylcholine receptor (Ki 6.8 μM), translocator protein (TSPO, Ki 4.1 μM), and serotonin transporter (SERT, Ki 6.1 μM). A lower dose of SCH442416 (0.6 mg/kg, i.p.) trended to increase activity (p=0.078) and Tb (p=0.10) by itself and largely blocked the hypothermia caused by PSB-0777 (1 mg/kg i.p.) (Fig. 5A-E). To distinguish a central vs peripheral site of action for A2AAR antagonism, we tested MRS7352 (Duroux et al., 2017), a polar derivative of SCH442416 that is unlikely to reach brain parenchymal A2AAR. Although less potent than SCH442416, MRS7352 retains selectivity for A2AAR (Table 1). MRS7352 (3 mg/kg, i.p.) completely blocked PSB-0777-induced hypothermia, without affecting physical activity (Fig 5F-J). These data further support a peripheral site of action of A2AAR agonists to cause hypothermia.

Fig. 5. Effect of A2AAR antagonists on PSB-0777-induced hypothermia.

(A–D) Tb and activity response to SCH442416 (0.6 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle at-15 min and then PSB-0777 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline at 0 min. (E) Structure of SCH442416. (F-I) Tb and activity response to MRS7352 (3 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle at-15 min and then PSB-0777 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline at 0 min. (J) Structure of MRS7352. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 5–12/group, *p < 0.05 or ***p <0.001 indicates significance at this level or better vs the other three groups by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparison testing.

3.4 A2AAR agonist-induced hypothermia is preceded by hypometabolism

A2AAR agonist-induced hypothermia (CGS-21680, 0.25 mg/kg, i.p.) was accompanied by a marked reduction in metabolic rate, with the hypometabolism preceding the hypothermia (energy expenditure nadir at ~26 vs ~65 minutes for Tb) (Fig. 6A-B). The hypothermia and hypoactivity were accompanied by reduced food intake, which likely contributes to the lower respiratory exchange ratio, indicating relatively more fatty acid oxidation (Fig. 6C-E).

Fig. 6. CGS-21680 reduces metabolic rate prior to Tb.

The effect of CGS-21680 (0.25 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle in C57BL/6J (WT) on (A) Tb, (B) total energy expenditure (TEE), (C) respiratory exchange ratio (RER), (D) physical activity, and (E) food intake. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 11/group, *p < 0.05.

3.5 Agonism at A2BAR causes hypothermia

We next examined if A2BAR agonism can also cause hypothermia. The non-nucleoside A2BAR agonist BAY60-6583 (0.5–2 mg/kg, i.p.) caused dose-dependent hypothermia and hypoactivity (Fig. 7A–C). BAY60-6583 shows modest adenosine receptor binding selectivity in mouse (Table 1) but appears to activate only mouse A2BAR and not mouse A1AR, A2AAR, or A3AR (van der Hoeven et al., 2011). BAY60-6583 also has a 5.6 μM Ki for SERT, from the PDSP screen. The BAY60-6583-induced hypothermia was abolished in Adora2b−/− mice (Fig. 7D-F), intact in Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice (not shown), and also intact in KitW−sh/W−sh mice (Fig. 7G-I). These results indicate that the hypothermia caused by BAY60-6583 is via A2BAR with little or no contribution from A1AR, A3AR, or mast cells.

Fig. 7. BAY60-6583 causes hypothermia and decreased physical activity via A2BAR.

(A-C) Tb and physical activity response to the indicated i.p. BAY60-6583 doses in C57BL/6J mice. (D-F) Tb and activity response to BAY60-6583 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle in C57BL/6J (WT) and Adora2b−/− mice. (G-I) Tb and activity response to BAY60-6583 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle in C57BL/6J (WT) and KitW−sh/W−sh mice. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 3–8/group; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs vehicle within genotype.

To further probe the sites of A2BAR agonist action, BAY60-6583 was given intracerebroventricularly, initially in Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice to avoid possible actions at A1AR or A3AR. A dose of 0.04 mg/kg produced profound, prolonged hypothermia, while 0.004 mg/kg had more modest effects (Fig. 8A-C). The lower dose (0.004 mg/kg, i.c.v.) caused hypothermia in C57BL/6J (wild type, WT) but not Adora2b−/− mice (Fig. 8D-F). These data suggest that the hypothermic effects of BAY60-6583 are via agonism at central (or central and peripheral) A2BAR.

Fig. 8. Intracerebroventricular BAY60-6583 causes hypothermia.

(A–C) Tb and physical activity response to BAY60-6583 (0.04 or 0.004 mg/kg, i.c.v.) in Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 7/group (vehicle, 0.004 mg/kg) or n =2 for 0.04 mg/kg. (D-F) Tb and physical activity response to BAY60-6583 (0.004 mg/kg, i.c.v.) or vehicle in Adora2b−/− or C57BL/6J (WT) mice. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 5–8/group in a crossover design; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs vehicle within genotype.

3.6 A2BAR agonist-induced hypothermia is driven by hypometabolism

The effect of BAY60-6583 was studied using indirect calorimetry, where it lowered metabolic rate, respiratory exchange ratio, and food intake, in addition to Tb and physical activity (Fig. 9A–E). The kinetics indicate that the reduction in metabolic rate is helping drive, not simply responding to the hypothermia.

Fig. 9. BAY60-6583 reduces metabolic rate before Tb.

The effect of BAY60-6583 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle in C57BL/6J (WT) mice on (A) Tb, (B) total energy expenditure (TEE), (C) respiratory exchange ratio (RER), (D) physical activity, (E) food intake. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 11/group, *p < 0.05.

3.7 A2BAR agonist induced hypothermia is accompanied by Fos induction in the preoptic area and the paraventricular hypothalamus

To identify candidate sites of BAY60-6583 action, we assessed neuronal activation after i.c.v. infusion (0.004 mg/kg, using Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice to preclude any effects via A1AR or A3AR). BAY60-6583, but not vehicle, increased Fos immunostaining in the preoptic area (POA) and paraventricular hypothalamus (PVH) (Fig. 10). Fos immunoreactivity was not significantly different in the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) or the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH), including subregions of the DMH (Wanner et al., 2017). These results indicate that A2BAR agonist causes neuronal activation in the PVH and POA, suggesting that these nuclei are involved in hypothermia.

Fig. 10. Neuronal activation after intracerebroventricular infusion of BAY60-6583.

(A) BAY60-6583 (0.004 mg/kg, i.c.v.) or vehicle was infused into in Adora1−/−;Adora3−/− mice, with brains removed 1 h later and stained for Fos. (A-D) Representative coronal Fos immunofluorescence images following vehicle (left) or BAY60-6583 (right) treatment. Nuclei are: POA, preoptic area; PVH, paraventricular hypothalamus; Arc, arcuate; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamus; and DMH, dorsomedial hypothalamus. (E) Quantitation of Fos-positive neurons. Means and p values are indicated.

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate that agonism of either peripheral A2AAR or central A2BAR causes hypothermia (Fig. S2). Thus, agonism at any one of the four canonical adenosine receptors, A1AR, A2AAR, A2BAR, or A3AR can cause hypothermia. The clear evidence demonstrating four mechanisms notwithstanding, our experiments do not rule out additional mechanisms of adenosine-induced hypothermia, such as intracellular depletion of ATP causing AMPK activation (Eisner et al., 2017; Melvin and Andrews, 2009).

4.1 Mechanism of A2AAR hypothermia

A2AAR are widely expressed in the cardiovascular, immune, and nervous systems. Brain-penetrant A2AAR antagonists acting on striatal neurons increase physical activity and are sometimes used clinically to treat Parkinson’s disease (Dungo and Deeks, 2013; Kulisevsky and Poyurovsky, 2012). However, our results suggest that brain A2AARs are not where A2AAR agonists initiate hypothermia. Supporting data include the observations that two poorly brain penetrant agonists, CGS-21680 and PSB-0777, cause hypothermia, that infusion of CGS-21680 into the brain did not produce hypothermia, and that MRS7352, a presumably non-brain penetrant A2AAR antagonist, inhibited the hypothermia. These data are consistent with the observation that the hypotensive effects of CGS-21680 in rats are mediated by peripheral A2AARs (Schindler et al., 2005).

The hypoactivity caused by treatment with an A2AAR agonist will reduce heat generation, but this probably makes a limited contribution to the reduced metabolic rate and hypothermia (Abreu-Vieira et al., 2015; Virtue et al., 2012). A peripheral mechanism that could contribute to A2AAR agonist-induced hypothermia is vasodilation, increasing heat loss. A2AAR agonists cause vasodilation in cerebral, mesenteric, renal, and coronary arteries (Al Jaroudi and Iskandrian, 2009; Hansen et al., 2005; Kleppisch and Nelson, 1995; Phillis, 2004), but the evidence for cutaneous vasodilation is modest (Fieger and Wong, 2010). In addition, heat loss from isolated vasodilation should elicit compensatory hypermetabolism for heat generation (Warner et al., 2013). In contrast, A2AAR agonist-induced hypothermia is accompanied by the opposite, severe hypometabolism. Thus, while A2AAR agonists cause vasodilation, they also trigger hypotension, hypoactivity, and hypometabolism. This coordinated response is likely a larger contributor to the hypothermia than heat loss from vasodilation.

The CGS-21680 doses causing hypothermia (e.g., 0.25 mg/kg, i.p.) are in the typical range of in vivo dosages used. Thus, the possible role of hypothermia and hypometabolism must be considered, as they could contribute to observed phenotypes. For example, the hypoactivity caused by peripheral CGS-21680 (El Yacoubi et al., 2000; Ledent et al., 1997) is likely peripherally initiated not due to agonism at brain A2AAR.

A2AAR are also present in multiple immune system cell types, which could contribute to driving the hypothermia. Our data rule out a role for mast cells. Further research is needed to define the cells (presumably in addition to vascular smooth muscle cells) on which A2AAR agonists act to cause hypothermia and how the panoply of physiology needed to achieve hypothermia is choreographed.

4.2 Mechanism of A2BAR hypothermia

A2BAR has a lower affinity for adenosine and more divergent synthetic ligand selectivity compared to the other three adenosine receptors. A2BAR are widely distributed, including in various hematopoietic cells, blood vessels, lung, astrocytes, and neurons (Fredholm et al., 2011; Goncalves et al., 2015; Lemos et al., 2015; Ohta and Sitkovsky, 2014). Hypothermia was produced by BAY60-6583 with an i.c.v. dose only 1/150th the amount of a similarly hypothermic i.p. dose. This suggests that A2BARs causing hypothermia are in the brain (or in both the brain and periphery). To identify where A2BAR agonists might act in the brain, we mapped the neurons activated during BAY60-6583-induced hypothermia, with drug given i.c.v. to preclude effects from peripheral A2BAR activation. A2BAR is coupled to Gs/q, so neurons are activated by BAY60-6583 action. The preoptic area of the hypothalamus (POA), a known thermoregulatory site (Morrison, 2016; Tan et al., 2016), was activated, as was the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH), which can inhibit thermogenesis (Madden and Morrison, 2009; Nakamura et al., 2017). The experiment was underpowered to detect lower levels of activation in the other regions studied. While neuronal activation could occur with rewarming the body to reverse the hypothermia, the 1-hour time point might minimize later contributions. Our data do not address whether the relevant A2BARs are on neurons or if the neuronal activation is indirect, due to agonist activation of astrocytes, vascular, immune system, or other cells (Sun and Huang, 2016).

4.3 A2AAR ligand selectivity

To identify adenosine receptor ligands as suitable tools for our in vivo mouse studies, we selected candidates based on rat or human affinity data and measured their binding affinity at mouse receptors. There can be profound species differences in adenosine receptor ligand affinities (Alnouri et al., 2015), and our results expand this literature. Examples of ligands binding more tightly to mouse A1AR than other species include: APEC, which is ~100-fold better than for rat (Kim et al., 1994), PSB-0777 which is >500-fold better than for rat (El-Tayeb et al., 2011), and regadenoson, which is >1000-fold better than for human (Gao et al., 2001). Thus, both PSB-0777 and regadenoson, which are A2AAR-selective in other species, are not selective in mouse, having both A1AR and A2AAR activity. Some of these differences might be due to the molecular environment of the binding measurement. For example, a 57-fold difference in ligand affinity for human A2AAR was observed, depending on which G-protein β subunit was present (Murphree et al., 2002). These examples underscore the risks of extrapolating ligand binding affinities across species, even between rat and mouse.

A drug’s utility strongly depends on pharmacokinetics in addition to binding affinity. Adenosine is useful for coronary vasodilation since intravenous dosing gives the high exposure to vascular tissue and the very short half-life limits adverse effects from wider exposure (Al Jaroudi and Iskandrian, 2009). Although not tested, intravenous regadenoson might appear selective in mouse vascular assays, since it should not reach brain A1AR. Similarly, pharmacokinetic considerations (lack of brain penetration) nullified N6-cyclopentyladenosine’s 2000-fold advantage in binding affinity (A1AR vs A3AR), so that this “A1AR” agonist initiated hypothermia via peripheral A3ARs (Carlin et al., 2017).

4.4 A2BAR ligands

BAY60-6583 is the most commonly used A2BAR agonist. It is a partial A2BAR agonist with a modest affinity (Ki at A2BAR =136 nM). BAY60-6583 also binds A1AR and, less well, A3AR, and is an antagonist at these receptors (Alnouri et al., 2015). Interestingly, in a cell-based assay BAY60-6583 had a 2.8 nM EC50 at mouse A2BAR, 50-fold better than the binding affinity (van der Hoeven et al., 2011). Notably, the hypothermia induced by BAY60-6583 was due to A2BAR, being completely abolished in the Adora2b−/− mouse. Thus, BAY60-6583 is a valid tool to study induction of hypothermia in mice by A2BAR.

4.5 Significance of A2AAR- and A2BAR-agonist induced hypothermia

Extracellular adenosine is a danger/injury signal, a general inducer of protective and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Combined with previous data, our results demonstrate that agonism at any adenosine receptor, A1AR, A2AAR, A2BAR, or A3AR, can cause hypothermia. Thus, the body has redundant ways to sense adenosine and triggers multiple mechanisms to achieve a common response, hypothermia. Of the four receptors, A1AR is the best studied and most directly implicated in the regulation of Tb, possibly having direct actions on brain thermoregulatory centers (Shintani et al., 2005; Tupone et al., 2013). The adenosine receptors probably do not have a major role in regulation of Tb in the non-challenged state: knockout of any one of the four receptors does not affect baseline Tb, its diurnal rhythm, or the ability to enter fasting-induced torpor ((Carlin et al., 2017; Carlin et al., 2016) and unpublished observations in Adora2a−/− and Adora2b−/− mice; but see (Yang et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2010)). The multiplicity of mechanisms that can sense adenosine and evoke hypothermia likely reflects the importance and centrality of the protective/anti-inflammatory effects of hypothermia.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Adenosine A2A agonists cause hypothermia via peripheral receptors

Adenosine A2B agonists cause hypothermia via central action

Adenosine A2B agonism activates preoptic area and paraventricular hypothalamic neurons

Acknowledgments

We thank Naili Liu, Anna Panyutin, Ramón Piñol, Atreyi Saha, Lex Kravitz, and Alice Franks for experimental contributions and advice, and the National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program and its Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply Program. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [ZIA DK075063; ZIA DK031117]

Abbreviations

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.c.v.

intracerebroventricular

- A×AR

adenosine × receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Chemical compounds

APEC, 2-[[2-[4-[2-(2-aminoethyl)-aminocarbonyl]ethyl]phenyl]ethylamino]-5′-N-ethyl-carboxamidoadenosine

BAY60-6583, 2-[6-amino-3,5-dicyano-4-[4-(cyclopropylmethoxy)phenyl]pyridin-2-ylsulfanyl]acetamide

CGS-21680, 2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

MRS7352, 4-((4-(3-(5-amino-2-(furan-2-yl)-7H-pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidin-7-yl)propyl)phenoxy)methyl)benzenesulfonate triethylammonium salt

PSB-0777, 4-[2-[(6-Amino-9-b-D-ribofuranosyl-9H-purin-2-yl)thio]ethyl]benzenesulfonic acid ammonium salt

Regadenoson, 1-[6-amino-9-[(2R,3R,4S,5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]purin-2-yl]-N-methylpyrazole-4-carboxamide

SCH442416, 2-(2-furyl)-7-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propyl]-7H-pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidin-5-amine

References

- Abreu-Vieira G, Xiao C, Gavrilova O, Reitman ML. Integration of body temperature into the analysis of energy expenditure in the mouse. Mol Metab. 2015;4:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Jaroudi W, Iskandrian AE. Regadenoson: a new myocardial stress agent. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alnouri MW, Jepards S, Casari A, Schiedel AC, Hinz S, Muller CE. Selectivity is species-dependent: Characterization of standard agonists and antagonists at human, rat, and mouse adenosine receptors. Purinergic Signal. 2015;11:389–407. doi: 10.1007/s11302-015-9460-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R, Sheehan MJ, Strong P. Characterization of the adenosine receptors mediating hypothermia in the conscious mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:1386–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi D, Strohm B, Marlow N, Brocklehurst P, Deierl A, Eddama O, Goodwin J, Halliday HL, Juszczak E, Kapellou O, Levene M, Linsell L, Omar O, Thoresen M, Tusor N, Whitelaw A, Edwards AD. Effects of hypothermia for perinatal asphyxia on childhood outcomes. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371:140–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet DW, Drury AN. Further observations relating to the physiological activity of adenine compounds. J Physiol. 1931;72:288–320. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1931.sp002775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borea PA, Gessi S, Merighi S, Varani K. Adenosine as a Multi-Signalling Guardian Angel in Human Diseases: When, Where and How Does it Exert its Protective Effects? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:419–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway CW, Donnino MW, Fink EL, Geocadin RG, Golan E, Kern KB, Leary M, Meurer WJ, Peberdy MA, Thompson TM, Zimmerman JL. Part 8: Post-Cardiac Arrest Care: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2015;132:S465–482. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin JL, Jain S, Gizewski E, Wan TC, Tosh DK, Xiao C, Auchampach JA, Jacobson KA, Gavrilova O, Reitman ML. Hypothermia in mouse is caused by adenosine A1 and A3 receptor agonists and AMP via three distinct mechanisms. Neuropharmacology. 2017;114:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin JL, Tosh DK, Xiao C, Pinol RA, Chen Z, Salvemini D, Gavrilova O, Jacobson KA, Reitman ML. Peripheral Adenosine A3 Receptor Activation Causes Regulated Hypothermia in Mice That Is Dependent on Central Histamine H1 Receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356:474–482. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Huang Z, Ma J, Zhu J, Moratalla R, Standaert D, Moskowitz MA, Fink JS, Schwarzschild MA. A(2A) adenosine receptor deficiency attenuates brain injury induced by transient focal ischemia in mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9192–9200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09192.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dungo R, Deeks ED. Istradefylline: first global approval. Drugs. 2013;73:875–882. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duroux R, Ciancetta A, Mannes P, Yu J, Boyapati S, Gizewski E, Yous S, Ciruela F, Auchampach JA, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. Bitopic fluorescent antagonists of the A2A adenosine receptor based on pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidin-5-amine functionalized congeners. Med Chem Commun. 2017;8:1659–1667. doi: 10.1039/c7md00247e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner C, Kim S, Grill A, Qin Y, Hoerl M, Briggs J, Castrop H, Thiel M, Schnermann J. Profound hypothermia after adenosine kinase inhibition in A1AR-deficient mice suggests a receptor-independent effect of intracellular adenosine. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1925-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Tayeb A, Michael S, Abdelrahman A, Behrenswerth A, Gollos S, Nieber K, Muller CE. Development of Polar Adenosine A2A Receptor Agonists for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Synergism with A2B Antagonists. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2:890–895. doi: 10.1021/ml200189u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Yacoubi M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Costentin J, Vaugeois J. SCH 58261 and ZM 241385 differentially prevent the motor effects of CGS 21680 in mice: evidence for a functional ‘atypical’ adenosine A(2A) receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;401:63–77. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00399-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieger SM, Wong BJ. Adenosine receptor inhibition with theophylline attenuates the skin blood flow response to local heating in humans. Exp Physiol. 2010;95:946–954. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.053538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca MT, Rodrigues AC, Cezar LC, Fujita A, Soriano FG, Steiner AA. Spontaneous hypothermia in human sepsis is a transient, self-limiting, and nonterminal response. J Appl Physiol. 2016;120:1394–1401. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00004.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, IJ AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Muller CE. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors–an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Li Z, Baker SP, Lasley RD, Meyer S, Elzein E, Palle V, Zablocki JA, Blackburn B, Belardinelli L. Novel short-acting A2A adenosine receptor agonists for coronary vasodilation: inverse relationship between affinity and duration of action of A2A agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:209–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilova O, Leon LR, Marcus-Samuels B, Mason MM, Castle AL, Refetoff S, Vinson C, Reitman ML. Torpor in mice is induced by both leptin-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14623–14628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser F. Metabolic rate and body temperature reduction during hibernation and daily torpor. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:239–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnad T, Scheibler S, von Kugelgen I, Scheele C, Kilic A, Glode A, Hoffmann LS, Reverte-Salisa L, Horn P, Mutlu S, El-Tayeb A, Kranz M, Deuther-Conrad W, Brust P, Lidell ME, Betz MJ, Enerback S, Schrader J, Yegutkin GG, Muller CE, Pfeifer A. Adenosine activates brown adipose tissue and recruits beige adipocytes via A2A receptors. Nature. 2014;516:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature13816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves FQ, Pires J, Pliassova A, Beleza R, Lemos C, Marques JM, Rodrigues RJ, Canas PM, Kofalvi A, Cunha RA, Rial D. Adenosine A2b receptors control A1 receptor-mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission in the mouse hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2015;41:878–888. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbaldeston MA, Chen CC, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Tam SY, Galli SJ. Mast cell-deficient W-sash c-kit mutant Kit W-sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:835–848. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62055-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen PB, Hashimoto S, Oppermann M, Huang Y, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Vasoconstrictor and vasodilator effects of adenosine in the mouse kidney due to preferential activation of A1 or A2 adenosine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:1150–1157. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hide I, Padgett WL, Jacobson KA, Daly JW. A2A adenosine receptors from rat striatum and rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells: characterization with radioligand binding and by activation of adenylate cyclase. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:352–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Kovarova M, Chason KD, Nguyen M, Koller BH, Tilley SL. Enhanced mast cell activation in mice deficient in the A2b adenosine receptor. J Exp Med. 2007;204:117–128. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JW, Scott IM. Daily torpor in the laboratory mouse, mus musculus var. albino. Physiol Zool. 1979;52:205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MF, Schulz R, Hutchison AJ, Do UH, Sills MA, Williams M. [3H]CGS 21680, a selective A2 adenosine receptor agonist directly labels A2 receptors in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B, Halldner L, Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA, Poelchen W, Gimenez-Llort L, Escorihuela RM, Fernandez-Teruel A, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu XJ, Hardemark A, Betsholtz C, Herlenius E, Fredholm BB. Hyperalgesia, anxiety, and decreased hypoxic neuroprotection in mice lacking the adenosine A1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9407–9412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161292398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HO, Ji XD, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5′-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleppisch T, Nelson MT. Adenosine activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in arterial myocytes via A2 receptors and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:12441–12445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreckler LM, Wan TC, Ge ZD, Auchampach JA. Adenosine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha release from mouse peritoneal macrophages via A2A and A2B but not the A3 adenosine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:172–180. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulisevsky J, Poyurovsky M. Adenosine A2A-receptor antagonism and pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease and drug-induced movement disorders. Eur Neurol. 2012;67:4–11. doi: 10.1159/000331768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lateef DM, Abreu-Vieira G, Xiao C, Reitman ML. Regulation of body temperature and brown adipose tissue thermogenesis by bombesin receptor subtype-3. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306:E681–687. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00615.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent C, Vaugeois JM, Schiffmann SN, Pedrazzini T, El Yacoubi M, Vanderhaeghen JJ, Costentin J, Heath JK, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Aggressiveness, hypoalgesia and high blood pressure in mice lacking the adenosine A2a receptor. Nature. 1997;388:674–678. doi: 10.1038/41771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos C, Pinheiro BS, Beleza RO, Marques JM, Rodrigues RJ, Cunha RA, Rial D, Kofalvi A. Adenosine A2B receptor activation stimulates glucose uptake in the mouse forebrain. Purinergic Signal. 2015;11:561–569. doi: 10.1007/s11302-015-9474-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden CJ, Morrison SF. Neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus inhibit sympathetic outflow to brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R831–843. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91007.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin RG, Andrews MT. Torpor induction in mammals: recent discoveries fueling new ideas. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SF. Central control of body temperature. F1000Res. 2016;5 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7958.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphree LJ, Marshall MA, Rieger JM, MacDonald TL, Linden J. Human A(2A) adenosine receptors: high-affinity agonist binding to receptor-G protein complexes containing Gbeta(4) Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:455–462. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.2.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzi M, Blasi F, Masi A, Coppi E, Traini C, Felici R, Pittelli M, Cavone L, Pugliese AM, Moroni F, Chiarugi A. Neurological basis of AMP-dependent thermoregulation and its relevance to central and peripheral hyperthermia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:183–190. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Yanagawa Y, Morrison SF, Nakamura K. Medullary Reticular Neurons Mediate Neuropeptide Y-Induced Metabolic Inhibition and Mastication. Cell Metab. 2017;25:322–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigrovic PA, Gray DH, Jones T, Hallgren J, Kuo FC, Chaletzky B, Gurish M, Mathis D, Benoist C, Lee DM. Genetic inversion in mast cell-deficient (Wsh) mice interrupts corin and manifests as hematopoietic and cardiac aberrancy. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1693–1701. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikodijevic O, Daly JW, Jacobson KA. Characterization of the locomotor depression produced by an A2-selective adenosine agonist. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80638-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Extracellular adenosine-mediated modulation of regulatory T cells. Front Immunol. 2014;5:304. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillis JW. Adenosine and adenine nucleotides as regulators of cerebral blood flow: roles of acidosis, cell swelling, and KATP channels. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2004;16:237–270. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v16.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires DE, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. pkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J Med Chem. 2015;58:4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore CA, Tilley SL, Latour AM, Fletcher DS, Koller BH, Jacobson MA. Disruption of the A(3) adenosine receptor gene in mice and its effect on stimulated inflammatory cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4429–4434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Karcz-Kubicha M, Thorndike EB, Muller CE, Tella SR, Ferre S, Goldberg SR. Role of central and peripheral adenosine receptors in the cardiovascular responses to intraperitoneal injections of adenosine A1 and A2A subtype receptor agonists. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:642–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafi S, Elliott AC, Gentilello L. Is hypothermia simply a marker of shock and injury severity or an independent risk factor for mortality in trauma patients? Analysis of a large national trauma registry. J Trauma. 2005;59:1081–1085. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000188647.03665.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani M, Tamura Y, Monden M, Shiomi H. Characterization of N(6)-cyclohexyladenosine-induced hypothermia in Syrian hamsters. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97:451–454. doi: 10.1254/jphs.sc0040178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Samuelson LC, Yang T, Huang Y, Paliege A, Saunders T, Briggs J, Schnermann J. Mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback by adenosine: evidence from mice lacking adenosine 1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9983–9988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171317998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Huang P. Adenosine A2B Receptor: From Cell Biology to Human Diseases. Front Chem. 2016;4:37. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2016.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CL, Cooke EK, Leib DE, Lin YC, Daly GE, Zimmerman CA, Knight ZA. Warm-Sensitive Neurons that Control Body Temperature. Cell. 2016;167:47–59 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todde S, Moresco RM, Simonelli P, Baraldi PG, Cacciari B, Spalluto G, Varani K, Monopoli A, Matarrese M, Carpinelli A, Magni F, Kienle MG, Fazio F. Design, radiosynthesis, and biodistribution of a new potent and selective ligand for in vivo imaging of the adenosine A(2A) receptor system using positron emission tomography. J Med Chem. 2000;43:4359–4362. doi: 10.1021/jm0009843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupone D, Madden CJ, Morrison SF. Central activation of the A1 adenosine receptor (A1AR) induces a hypothermic, torpor-like state in the rat. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14512–14525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1980-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoeven D, Wan TC, Gizewski ET, Kreckler LM, Maas JE, Van Orman J, Ravid K, Auchampach JA. A role for the low-affinity A2B adenosine receptor in regulating superoxide generation by murine neutrophils. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:1004–1012. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.181792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtue S, Even P, Vidal-Puig A. Below thermoneutrality, changes in activity do not drive changes in total daily energy expenditure between groups of mice. Cell Metab. 2012;16:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner SP, Almeida MC, Shimansky YP, Oliveira DL, Eales JR, Coimbra CC, Romanovsky AA. Cold-Induced Thermogenesis and Inflammation-Associated Cold-Seeking Behavior Are Represented by Different Dorsomedial Hypothalamic Sites: A Three-Dimensional Functional Topography Study in Conscious Rats. J Neurosci. 2017;37:6956–6971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0100-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner A, Rahman A, Solsjo P, Gottschling K, Davis B, Vennstrom B, Arner A, Mittag J. Inappropriate heat dissipation ignites brown fat thermogenesis in mice with a mutant thyroid hormone receptor alpha1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16241–16246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310300110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan TD, Bannon PG, Bavaria J, Coselli JS, Elefteriades JA, Griepp RB, Hughes GC, LeMaire SA, Kazui T, Kouchoukos NT, Misfeld M, Mohr FW, Oo A, Svensson LG, Tian DH. Consensus on hypothermia in aortic arch surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2:163–168. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.03.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JN, Tiselius C, Dare E, Johansson B, Valen G, Fredholm BB. Sex differences in mouse heart rate and body temperature and in their regulation by adenosine A1 receptors. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;190:63–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2007.01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JN, Wang Y, Garcia-Roves PM, Bjornholm M, Fredholm BB. Adenosine A(3) receptors regulate heart rate, motor activity and body temperature. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;199:221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.