Introduction

Topical anesthesia with lidocaine is one of the cornerstones of performing a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) exam in awake patients. There are a number of different techniques of oropharyngeal topicalization with lidocaine including the direct application of viscous lidocaine or lidocaine ointment or the nebulization and/or atomization of lidocaine solution. Rapid administration of large doses of local anesthetics such as lidocaine are known to cause toxicity. Guidelines for the use of subcutaneous lidocaine suggest a maximum dose of 4.5 mg/kg but do not specify maximal doses for topical anesthesia with lidocaine.(1) Because the majority of the lidocaine dose administered during oropharyngeal topicalization is either swallowed or inhaled, the pharmacokinetics and potential for toxicity likely differ than that of intravenous or subcutaneous lidocaine, and maximal doses to prevent toxicity are unknown. We present a case of a patient who developed local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) after oropharyngeal topical anesthesia with lidocaine prior to TEE and her subsequent treatment with extracorporeal life support (ECLS).

Case Presentation

A 76 year old female with history of heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction, moderate mitral regurgitation, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity (BMI=35), and hypothyroidism was scheduled to undergo outpatient transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and cardioversion for atrial fibrillation. Nine days prior to the procedure, the patient was admitted to the hospital for shortness of breath, lower extremity edema, and fatigue and was found to have new-onset atrial fibrillation. The patient was treated with warfarin, enoxaparin, carvedilol, and intravenous furosemide for heart failure exacerbation, then underwent synchronized electrical cardioversion. She remained in sinus rhythm for 12 hours but converted back to atrial fibrillation. Rate control was achieved with beta-blockade, anticoagulation was arranged, and the patient was discharged on hospital day 3 with plans for outpatient cardioversion.

On the day of the procedure, consent for TEE and cardioversion were obtained. During preparation for the TEE, the patient was given approximately three doses of 25–30 mL 4% topical lidocaine and two additional doses of 20–30 mL 2% topical lidocaine for an approximate total of 3000 mg (36 mg/kg) of lidocaine. Importantly, she did not receive any other medications for sedation at this time. About 45 minutes after the administration of lidocaine, she developed slurred speech and confusion. She became bradycardic with a heart rate in the 40s, and hypoxic with oxygen saturations of 80%. Supplemental oxygen was given and the rapid response team was called, after which the patient was rapidly transported to the Emergency Department (ED). During transport, the patient’s confusion progressed to combativeness and she eventually became unresponsive.

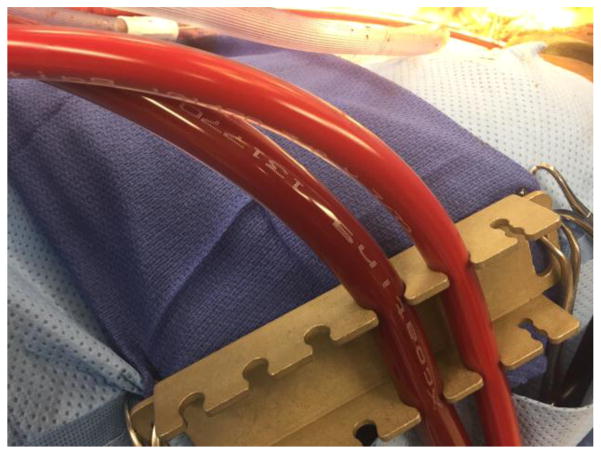

Upon arrival in the ED the patient was unresponsive, hemodynamically stable with normal vitals except for agonal breaths that required bag-valve-mask ventilation. Shortly after arrival, she began to display seizure activity and her pupils were noted afterwards to be dilated. She was intubated, given lorazepam for seizures, and 10% intravenous fat emulsion (Intralipid) for lidocaine toxicity, which was titrated up to the maximum recommended dose of 10mL/kg. Despite this, bradycardia and hypotension progressed to pulselessness, and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) including chest compressions was started. The patient underwent multiple rounds of resuscitation and was treated with atropine, magnesium, calcium, and bicarbonate. After 60 minutes, return of spontaneous circulation was achieved with HR 20–30 bpm and mean arterial pressures (MAPs) ~50mmHg. Transcutaneous pacing was attempted with poor capture and the patient again became pulseless. A transvenous pacer was placed with good capture but hypotension and intermittent pulselessness persisted. Cardiothoracic surgery was consulted for ECMO placement. A CT scan was performed to rule out intracranial hemorrhage. The patient was taken to the operating room (OR) for cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), hemofiltration and possible extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Cardiopulmonary bypass cannulation was uneventful, but during CPB, it was noted that the blood had a distinctively milky appearance due to the intra-lipid, most appreciable in the arterial cannula (Figure 1, right side). After 64 minutes, an attempt was made to wean the patient from CPB but severe right ventricular dysfunction and respiratory failure persisted. The patient was therefore placed on VA-ECMO and transported to the Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit in critical condition.

Figure 1.

Tubing connected to the Venous cannula (left) and arterial cannula (right) of the patient on VA-ECMO. The milky appearance of the arterial blood is noted after receiving the recommended maximum dose of Intralipid of 10mL/kg.

The following day the patient remained on ECMO with intact brain stem function, including cough and gag reflexes. However, she was minimally responsive with fixed and dilated pupils despite receiving no sedation. Electroencephalogram demonstrated no evidence of epileptiform activity. The first lidocaine level was drawn on post arrest day 1 and was 1.8μg/mL, well within safe therapeutic range (1.2–5μg/mL). By the end of day 1 post arrest, the patient had regained pupillary responses and by post arrest day 2, the patient was awake and interactive with an unremarkable neurological exam. A turndown was performed with TEE demonstrating continued atrial fibrillation, atrial enlargement, and biventricular function. On post arrest day 3, the patient was taken to the OR for ECMO de-cannulation. Acute kidney injury secondary to acute tubular necrosis was the only persistent sequelae and this resolved prior to discharge. The patient was discharged to a skilled nursing facility on post arrest day 11 for continued rehabilitation with no apparent major neurologic deficits.

Discussion

Lidocaine is a procaine class anesthetic that is widely used in healthcare for procedures involving pain or discomfort. In addition to its anesthetic properties, lidocaine is also a class IB antiarrhythmic because of its function as a potent sodium channel blocker. Thus conduction is inhibited both in the nervous system and in cardiac myocardium, hence the potential for both neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity in excessive doses.

Lidocaine is metabolized and cleared primarily by the liver with approximately 70% of the drug undergoing first pass clearance when absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract. Several of the metabolites have antiarrhythmic properties and are thought to act on the central nervous system as well. The drug exhibits biphasic kinetics due in part to its lipophilicity with a short primary half-life of approximately 17 min as concentrations build up in the adipose tissue and then a second longer half-life is around 2 hours (2).

Local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) is a rare syndrome classically characterized by CNS excitatory symptoms such as auditory changes, circumoral numbness, metallic taste, and agitation leading to seizures and/or CNS depression, followed by cardiotoxicity and arrest (3). First described by Mayer in 1928 (4), the exact incidence is unknown. Studies have shown the incidence of LAST during peripheral nerve blockade was 2.5–9.8 per 10,000 (5–7). Another study reported a 6.3% overdose rate of IV lidocaine when used as an antiarrhythmic, and 25% of those cases were life-threatening (8). The incidence of LAST after oropharyngeal topicalization is unknown.

Signs and symptoms of lidocaine toxicity vary by the concentration levels of the drug. At low levels (5–7μg/mL), dizziness, disorientation, excitement, speech changes, nystagmus, hypertension, tachycardia, tachypnea, and loss of consciousness can be seen. At moderate to high concentrations (>7μg/mL) the symptoms progress to generalized tonic-clonic seizures, CNS depression and apnea, depressed cardiovascular function, hypoxia, hypercarbic acidosis, hypotension, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest (2). The recommended maximum dose for subcutaneous lidocaine is 4.5mg/kg(1), but when lidocaine is applied topically for oropharyngeal anesthesia during awake TEE or awake fiber optic intubation, the majority of the dose is ingested and cleared during first pass metabolism. The maximum safe dose of topicalized lidocaine in the oropharynx, is therefore unknown. Williams et al applied topical lidocaine of up to 9mg/kg (twice the maximum recommended subcutaneous dose) in patients having awake fiber optic intubation and found that plasma lidocaine concentrations in these patients all were below 5 mcg/ml (the minimal concentration to trigger minor symptoms of lidocaine toxicity).(9) The dose of topical lidocaine in this patient, however, greatly exceeded even these doses.

The treatment of LAST is primarily supportive. Noninvasive monitors, if not already on the patient, should be applied. Airway control may be needed in cases of respiratory insufficiency. Ventilation with 100% oxygen with slight hyperventilation is used to prevent acidosis. Neurologic effects such as seizures can often be suppressed with benzodiazepines. Basic and advanced life support may need to be instituted to manage cardiac arrhythmias and arrest due to LAST, but these algorithms should be modified in this setting. Epinephrine is still recommended as the drug of choice for LAST induced cardiac arrest, but because of the increased disposition for arrhythmia, bolus doses of epinephrine should remain start at 10 – 100 mcg rather than the 1 mg recommended with standard ACLS. In animal studies of LAST, vasopressin resulted in poor outcomes and is not recommended in these patients.(10) Finally, drugs that delay conduction through the AV node are avoided (lidocaine, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone).(3)

Current American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) recommendations include initiating lipid rescue therapy at the first signs of LAST after securing the airway (3). The lipid emulsion comes in a 20% concentration (200mg/mL). An initial bolus of 1.5 mL/kg is given followed by an infusion of 0.25 mL/kg/min. The bolus can be repeated up to two additional times for refractory arrhythmias, and the infusion can be increased to 0.5 mL/kg/min. The upper limit dose over the first 30 minutes is 10mL/kg.

In patients with cardiopulmonary instability despite intralipid, consideration should be given to alerting the nearest facility capable of extracorporeal life support (ECLS). The use of extracorporeal life support ECLS—most commonly VA-ECMO—for cardiopulmonary collapse due to medication overdose has been well described (11–13), and appears to be cost effective (14), though large series are limited (15). In a recent review of emergency department ECMO for cardiopulmonary collapse due to cardio toxic drugs by Johnson et al, the most common medications were calcium channel blockers and antiarrhythmics (16). The use of ECMO as a rescue strategy for severe local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) was first described in dogs in the early 1980s, but has yet to be described in humans (17).

The effect of the ECMO circuit on drug adsorption has been studied, and is highly variable (18–22). Additionally, as LAST is treated with Intralipid, the effect of lipid heavy solutions on the ECMO circuit has been described (18, 23). In in vitro studies and clinical cases, the most common complications include fat deposition and earlier clot formation, which would be expected to both shorten the life of the oxygenator and potentially increase the risk of thrombotic stroke. To our knowledge, the clinical use of ECMO for lidocaine induced cardiopulmonary collapse has not been described.

Conclusion

We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with ECMO after cardiac arrest secondary to LAST from approximately 3000mg (34.5mg/kg) of topical lidocaine prior to transesophageal echocardiography (the highest reported single dose of lidocaine in an adult) (2, 24–27). While reports of LAST are rare, the profound refractory cardiac arrest associated with significant toxicity may not respond to first line therapies, and extracorporeal life support may be required in severe cases.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This investigation was supported by the University of Utah Population Health Research (PHR) Foundation, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 5UL1TR001067-05 (formerly 8UL1TR000105 and UL1RR025764).

We are grateful the nurses and staff of the University of Utah Cardiovascular ICU, the Emergency Department and the Operating Room for their excellent care.

List of abbreviations

- ACLS

Advanced Cardiac Life Support

- ASRA

American Society of Regional Anesthesia

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- CPB

Cardiopulmonary Bypass

- ECLS

Extracorporeal Life Support

- ECMO

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

- ED

Emergency Department

- LAST

Lidocaine Associated Systemic Toxicity

- OR

Operating Room

- VA-ECMO

Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

Footnotes

Declarations

Ethics approval to participate

This case report was covered under University of Utah Institutional Review Board # IRB_00084463.

Consent for publication

Written consent from the patient was attained to use their case for publication and to use the photograph of their apparatus.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

DB, EH, JH and JT conceived the idea. BB performed the literature review, authored the manuscript and compiled the final manuscript from the other authors. MK, EH, JH, DB, NS and JT all contributed to writing and editing sections of the manuscript. JT oversaw the literature review, and edited the compilation of the work by BB. JT takes full responsibility for the integrity of the manuscript from start to finish.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Brandon Bacon, University of Utah School of Medicine, 30 N. 1900 E, Salt Lake City, Utah 84132.

Natalie Silverton, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Utah, 30 N 1900 E, Salt Lake City, Utah 84132.

Micah Katz, Department of Surgery, University of Utah, 30 N 1900 E, Salt Lake City, Utah 84132.

Elise Heath, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Utah, 30 N 1900 E, Salt Lake City, Utah 84132.

David A. Bull, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Utah, 30 N 1900 E, Salt Lake City, Utah 84132.

Jason Harig, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Utah, 30 N 1900 E, Salt Lake City, Utah 84132.

Joseph E. Tonna, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Surgery, University of Utah, 30 N 1900 E, Salt Lake City, Utah 84132.

References

- 1.Kouba DJ, LoPiccolo MC, Alam M, et al. Guidelines for the use of local anesthesia in office-based dermatologic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1201–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mofenson HC, Caraccio TR, Miller H, et al. Lidocaine toxicity from topical mucosal application. With a review of the clinical pharmacology of lidocaine. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1983;22(3):190–192. doi: 10.1177/000992288302200306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neal JM, Bernards CM, Butterworth JF, et al. ASRA practice advisory on local anesthetic systemic toxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(2):152–161. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181d22fcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruetsch YA, Böni T, Borgeat A. From cocaine to ropivacaine: the history of local anesthetic drugs. Curr Top Med Chem. 2001;1(3):175–182. doi: 10.2174/1568026013395335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L, et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline Service. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(5):1274–1280. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200211000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrington MJ, Watts SA, Gledhill SR, et al. Preliminary results of the Australasian Regional Anaesthesia Collaboration: a prospective audit of more than 7000 peripheral nerve and plexus blocks for neurologic and other complications. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(6):534–541. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181ae72e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrington MJ, Kluger R. Ultrasound guidance reduces the risk of local anesthetic systemic toxicity following peripheral nerve blockade. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38(4):289–299. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e318292669b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfeifer HJ, Greenblatt DJ, Koch-Weser J. Clinical use and toxicity of intravenous lidocaine. A report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. Am Heart J. 1976;92(2):168–173. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(76)80252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams KA, Barker GL, Harwood RJ, et al. Combined nebulization and spray-as-you-go topical local anaesthesia of the airway. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95(4):549–553. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Gregorio G, Schwartz D, Ripper R, et al. Lipid emulsion is superior to vasopressin in a rodent model of resuscitation from toxin-induced cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):993–999. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181961a12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escajeda JT, Katz KD, Rittenberger JC. Successful treatment of metoprolol-induced cardiac arrest with high-dose insulin, lipid emulsion, and ECMO. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(8):1111e1111–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heise CW, Skolnik AB, Raschke RA, et al. Two Cases of Refractory Cardiogenic Shock Secondary to Bupropion Successfully Treated with Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J Med Toxicol. 2016;12(3):301–304. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0539-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maskell KF, Ferguson NM, Bain J, et al. Survival After Cardiac Arrest: ECMO Rescue Therapy After Amlodipine and Metoprolol Overdose. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12012-016-9362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St-Onge M, Fan E, Mégarbane B, et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for patients in shock or cardiac arrest secondary to cardiotoxicant poisoning: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Crit Care. 2015;30(2):437e437–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daubin C, Lehoux P, Ivascau C, et al. Extracorporeal life support in severe drug intoxication: a retrospective cohort study of seventeen cases. Crit Care. 2009;13(4):R138. doi: 10.1186/cc8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson NJ, Gaieski DF, Allen SR, et al. A review of emergency cardiopulmonary bypass for severe poisoning by cardiotoxic drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(1):54–60. doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0281-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedman MD, Gal J, Freed CR. Extracorporeal pump assistance--novel treatment for acute lidocaine poisoning. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;22(2):129–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00542457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers GJ, Voorhees C, Eke B, et al. The effect of Diprivan (propofol) on phosphorylcholine surfaces during cardiopulmonary bypass--an in vitro investigation. Perfusion. 2009;24(5):349–355. doi: 10.1177/0267659109353819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preston TJ, Hodge AB, Riley JB, et al. In vitro drug adsorption and plasma free hemoglobin levels associated with hollow fiber oxygenators in the extracorporeal life support (ECLS) circuit. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2007;39(4):234–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spriet I, Annaert P, Meersseman P, et al. Pharmacokinetics of caspofungin and voriconazole in critically ill patients during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(4):767–770. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tron C, Leven C, Fillatre P, et al. Should we fear tubing adsorption of antibacterial drugs in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation? An answer for cephalosporins and carbapenems. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;43(2):281–283. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner D, Pasko D, Phillips K, et al. In vitro clearance of dexmedetomidine in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 2013;28(1):40–46. doi: 10.1177/0267659112456894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HM, Archer JR, Dargan PI, et al. What are the adverse effects associated with the combined use of intravenous lipid emulsion and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the poisoned patient? Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53(3):145–150. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1004582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tierney KJ, Murano T, Natal B. Lidocaine-Induced Cardiac Arrest in the Emergency Department: Effectiveness of Lipid Therapy. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(1):47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanawuttiwat T, Thisayakorn P, Viles-Gonzalez JF. LAST (local anesthetic systemic toxicity) but not least: systemic lidocaine toxicity during cardiac intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2014;26(1):E13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown DL, Skiendzielewski JJ. Lidocaine toxicity. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9(12):627–629. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(80)80475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamashita S, Sato S, Kakiuchi Y, et al. Lidocaine toxicity during frequent viscous lidocaine use for painful tongue ulcer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(5):543–545. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]