Highlights

-

•

Adrenergic hyperstimulation states can lead to different grades of myocardial dysfunction.

-

•

Cardiomyopathy of unknown origin can be caused by an underlying pheochromocytoma.

-

•

The onset of adrenergic myocardiopathy as cardiogenic shock is exceptional.

-

•

The reversibility of myocardial affection is common after pheochromocytoma resection.

-

•

Delayed phechromocytoma resection may lead to irreversible cardiac affection and death.

Keywords: Catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy, Pheocromocytoma, Adrenergic myocarditis, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Pheochromocytomas are infrequent tumors arised from the chromaphine cells of the adrenal sympathetic system. The excess of circulating catecholamines may lead to different cardiovascular disorders from silent alterations of the myocardial conduction to different forms of cardiomyopathy. The onset as cardiogenic shock is exceptional.

Presentation of case

A 35—year-old male, with a known history of acute myopericarditis of unknown origin which debuted as acute pulmonary edema, was admitted with dyspnea in the context of a new heart failure episode with pulmonary edema. An initial ECG showed segmentary repolarization changes, reversed in subsequent ECGs. The echocardiogram showed severe left ventricular dysfunction and lateral and apical hypokinesia. Subsequent echocardiograms showed partial recovery of alterations and preserved systolic function. A cardiac MRI showed a subepicardial minimum catchment focus and myocardial edema suggestive of adrenergic myocarditis. A solid nodular lesion was found in the left adrenal gland, suggesting a pheochromocytoma. Laparoscopic left adrenalectomy confirmed a 30 mm adrenal tumor without signs of locoregional invasion. The patient had normal catecholamine excretion and heart function a few weeks after surgery. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma.

Discussion and conclusions

Adrenergic cardiomyopathy is a rare entity with a variable clinical presentation. The onset as cardiogenic shock is exceptional. The differential diagnosis of a patient with cardiogenic shock of unknown origin should consider the presence of an underlying pheocromocytoma as well as other states of adrenergic hyperstimulation. The reversibility of the myocardial affection in pheocromocytoma-associated myocardiopathy is common after the tumor resection.

1. Introduction

Pheocromocytomas are cathecolamine-producing tumors arised from the adrenal medulla or the intraabdominal paraganglionic tissue. They produce, secrete and store adrenaline and/or noradrenaline, as well as other peptides such as cromogranine A, somatostatine or PTH-like peptide. Extra-adrenal tumors are generally noradrenaline-secretors, while the exclusive secretion of adrenaline is infrequent and is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasms.

The clinical presentation of pheocromocytomas is highly variable; therefore, the differential diagnosis can become a real challenge. The most frequent manifestation is paroxysmal or maintained hypertension, which is present in more than the 60% of patients. Other symptoms include palpitations, hyperthermia, diaphoresis, headache and abdominal pain.

Elevated circulating catecholamines and its oxidation products can cause cardiovascular alterations of variable severity related to coronary vasospasm, ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias and dilated cardiomyopathy among others. We present a rare case of adrenergic cardiomyopathy and cardiogenic shock as the initial presentation of a pheochromocytoma. This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [1].

2. Presentation of case

A 35—year-old man was admitted in the emergency unit of our hospital with a NYHA Class IV dyspnea in the context of an acute pulmonary edema without hypertension. He was a former smoker and a former morbid obese (at the time of admission he had a BMI of 26 kg/m2 after a year of strict diet and exercise). His past medical history was also relevant for a previous episode of acute myopericarditis seven years before, after an episode of fever and odynophagia, that led to acute pulmonary edema requiring admission to the intensive coronary care unit. At that time, an echocardiogram was performed showing a slightly hypertrophied left ventricle, with an ejection fraction of 30%, akinesia of the interventricular septum and inferolateral hypokinesia, without pericardial effusion. After usual inotropic and depletive treatment, the patient presented an adequate clinical evolution and recovered systolic function. No subsequent cardiac monitoring was performed.

At the current admission, the initial EKG showed sinus tachycardia, short QRS and repolarization alterations with 0,5 mm elevation of the ST segment in DI and aVL, ST depression <1 mm in DII, DIII and aVF, and ST depression >1 mm in V3–V6, reaching of 2,5 mm in V4. A CBC, troponins, arterial blood gasometry and chest X ray were also performed, showing mild anemia and leukocytosis with left deviation; slight elevation of troponins; acute respiratory acidosis; and radiological findings compatible with acute pulmonary edema respectively. And echocardiogram was also performed showing moderate left ventricle dysfunction and apical and lateral hypokinesia.

At the ER, intensive depletive treatment was initiated. Two hours after admission, the patient presented severe hypotension (systolic BP of 60 mmHg), bradycardia and oliguria, requiring vasoactive amines for hemodynamic stabilization. The patient was admitted to the Coronary Intensive Care Unit, where the systolic dysfunction and ECG alterations were reversed a few hours later. A new echocardiogram realized 48 h after the acute phase revealed partial recovery of the segmental contractility alterations, mild septal hypokinesia and a systolic function of 54%. In addition, mild left ventricular hypertrophy and moderate dilatation of the left atrium (that were not present on a previous echocardiography performed years before) were detected. A coronary angiography was carried out three days after admission, showing no significant coronary abnormalities.

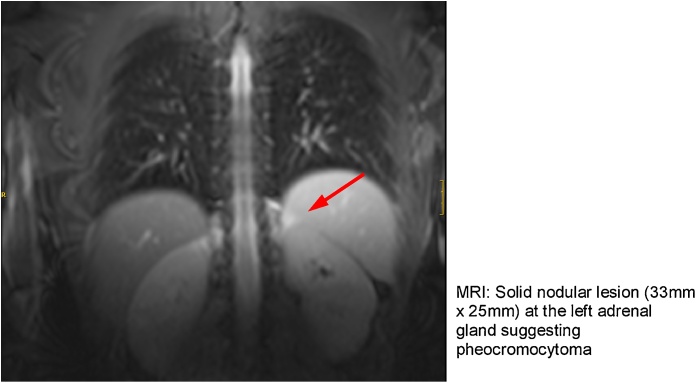

Suspecting the etiological possibility of an adrenergic crisis due to the fast and spontaneous recovery of the evidenced non-ischemic cardiac alterations, a cardiac and suprarenal MRI was performed. The exploration showed a preserved systolic function (EF 58%) and a slight inferobasal hypocinesia. A solid nodular lesion of 33 mm × 25 mm in size was identified at the left adrenal gland, confirming the presence of a pheochromocytoma. The delayed enhancement study after contrast administration showed a focus of supbepicardial and inferobasal contrast uptake of non-ischemic origin and faint myocardial edema in pre-contrast sequences, suggesting adrenergic myocarditis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Radiologic Findings.

MRI: Solid nodular lesion (33 mm x 25 mm) at the left adrenal gland suggesting pheocromocytoma.

After his clinical improvement, the patient was admitted to the Endocrinology Unit for evaluation, and elevated catecholamine excretion in 24 h urine was demonstrated. No pathologic noradrenergic activity was detected in the gammagraphic exploration with MIBG-123I.

The patient received alpha and beta medical blockage for 20 days, and 30 days after the initial ER admission, he underwent a laparoscopic anterior left adrenalectomy. A 30 mm tumor without sings of invasion of adjacent structures was identified during surgery. The postoperative course was favorable, and the patient remained hemodynamically stable with normal tensional controls. The patient was discharged at the third postoperative day.

During the follow up, the patient maintained a normalized catecholamine excretion. A MRI realized six weeks after surgery showed a significant decrease of the subepicardic enhancement without segmentary alterations of the contractibility and a preserved ejection function of 63%. The pathology was conclusive and confirmed the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma without signs of malignancy.

3. Discussion

Pheochromocytomas are infrequent tumors, with an incidence of 1–2 cases per 1,000,000 adults [2]. They are usually sporadic; however, they can appear in the context of multiple endocrine neoplasms or other diseases such as neurofibromatosis or the Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. They usually present a benign course; however, around 10% present signs of malignancy [2].

Regarding clinical presentation, the overproduction of catecholamines is associated with the presence of hypertension in about 60% of patients, but only 1 in 4 patients present the classic triad with headache, palpitations and diaphoresis [3]. A recent review has reported even a lower rate of triad symptoms (around 4%) in patients with diagnoses of adrenergic cardiomyopathy [4]. The absence of hypertension or suggestive symptoms is found in more than 30% of the cases of pheochromocytoma [3,4]. Indeed, results from autopsies suggest a non-depreciable proportion of undiagnosed cases, with the consequent associated morbi-mortality [5]. This infradiagnosis could be related with the great variability in the presentation of this clinical entity, also known as “the great masquerader”.

The elevated circulating catecholamines can lead to different cardio-vascular effects. It’s been reported that 25% of patients with a pheochromocytoma have some grade of myocardial dysfunction [6]. However, diagnosis of pheocromocytoma-related cardiomyopathies is often delayed due to the atypical presentation of this heterogeneous entity.

The pathogenesis of catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy is multifactorial [7]. Persistent high levels of catecholamines have been related with the dysregulation of beta-adrenergic receptors, myofibril dysfunction and reduction of the contractile units [8]. Actually, direct myocardial damaged of catecholamines and its oxidation products have also been related to increased sarcolemma permeability, with increased cytosolic concentration of calcium, and with even direct myocardial necrosis [9]. In addition, the maintained adrenergic stimulation also generates an intense vasoconstriction and coronary spasm, which aggravates the myocardial damage [10]. In fact, focal myocardial necrosis and inflammatory cells are present in 50% of patients who die with a pheochromocytoma, and these findings could be related to clinically significant ventricular dysfunction [11].

The prognosis of patients with pheocromocytoma-associated adrenergic cardiomyopathy depends greatly on an early diagnosis and a prompt treatment, which are often delayed because of the challenging diagnosis in many cases.

The reversibility of the myocardial affection after adrenalectomy has been described in cases of mild myocardial damage [[12], [13], [14]], but it is not possible in case of massive necrosis or extensive myocardial fibrosis [12], where the prognosis becomes poor. According to a recent review published by Zhang et al. [4], there are 161 cases of adrenergic cardiomyopathy found in the literature in the last thirty years (63 dilated cardiomyopathy, 38 Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, 30 inverted Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, 10 HOCM, 8 myocarditis, and 14 unspecified cardiomyopathy). As stated in this review, resection of the pheochromocytoma led to improvement of the cardiomyopathy in 96% of patients, while lack of resection was associated with dead or cardiac transplantation in 44% of cases.

Apart from the presence of a pheocromocytoma, other states of catecholamines excess can cause some grade of adrenergic cardiomyopathy such as: stress (Takotsubo’s syndrome), prolonged use of inhalers with sympathomimetic agents, abuse of methamphetamines, certain scorpion venoms and septic states [7]. Therefore, in the evaluation of non-ischemic, non-valvular cardiomyopathy, or cardiogenic shock of unknown origin, the differential diagnosis should consider the presence of an underlying pheocromocytoma as well as other states of adrenergic hyperstimulation, even in the absence of symptoms of catecholamine excess.

4. Conclusion

Adrenergic cardiomyopathy is a rare entity with a variable clinic presentation, where patients can present different grades of acute ventricular dysfunction. The presentation as adrenergic myocarditis is rare, and the onset with cardiogenic shock is exceptional.

Pheochromocytoma and other adrenergic hyperstimulation states must be considered in the evaluation of cardiomyopathy of unknown origin, even in the absence of classic symptoms.

Given the potential reversibility of the cardiac dysfunction, early diagnosis and resection of the pheochromocytoma is crucial. Delayed diagnosis and treatment may lead to irreversible cardiac affection and death.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

This study is exempt from ethnical approval in our institution.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author’s contribution

Esther Gil-Barrionuevo: study concept and design, data collection and analysis, writing the paper.

José Maria Balibrea: study concept and design, data analysis.

Enric Caubet, Oscar Gonzalez, Ramón Vilallonga, José Manuel Fort, Andrea Ciudin, Manel Armengol: data analysis.

Registration of research studies

None.

Guarantor

Esther Gil-Barrionuevo.

Aknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34(October):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oleaga A., Goñi F. Feocromocitoma: Actualización diagnóstica y terpéutica. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2008;55(5):202–216. doi: 10.1016/S1575-0922(08)70669-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopetsche R. Frequent incidental discovery of phaeochromocytoma: data from a German cohort of 201 phaeochromocytoma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2009;161(August (2)):355–361. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang R., Gupta D., Albert S.G. Pheochromocytoma as a reversible cause of cardiomyopathy: analysis and review of the literature. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017;15(December (249)):319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheps S.G., Jiang N.S., Klee G.G., Van Heerden J.A., Mayo Recent developments in the diagnosis and treatment of pheochromocytoma. Clin. Proc. 1990;65:88–95. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schürmeyer T.H., Engeroff B., Dralle H., von zur Mühlen A. Cardiological effects of catecholamine secreting tumours. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;27:189–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1997.850646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassim T.A., Clarke D.D., Mai V.Q., Clyde P.W., Shakir K.M.M. Catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy. Endocr. Pract. 2008;14(December (9)):1137–1149. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.9.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fripp R.R., Lee J.C., Downing S.E. Inotropic responsiveness of the heart in catecholamine cardiomyopathy. Am. Heart J. 1981;101:17–21. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleckenstein A., Janke J., Doring H.J., Pachinger O. Ca overload as the determinant factor in the production of catecholamine induced myocardial lesion. In: Bajusz E., Rona G., Brink A.J., Lochner A., editors. vol. 2. University Park Press; Baltimore, MD: 1973. pp. 455–466. (Recent Advances in Studies on Cardiac Structure and Metabolism). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downing S.E., Chen V. Myocardial injury following endogenous catecholamine release in rabbits. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1985;17:377–387. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roghi A. Adrenergic myocarditis in pheochromocytoma. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2011;11(January (13)):4. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadowski D., Cujec B., McMeekin J.D., Wilson T.W. Reversibility of catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy in a woman with pheochromocytoma. CMAJ. 1989;141:923–924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood R., Commerford P.J., Rose A.G., Tooke A. Reversible catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy. Am. Heart J. 1991;121(2 (Pt. 1)):610–613. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90740-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quezado Z.N., Keiser H.R., Parker M.M. Reversible myocardial depression after massive catecholamine release from a pheochromocytoma. Crit. Care Med. 1992;20:549–551. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199204000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]