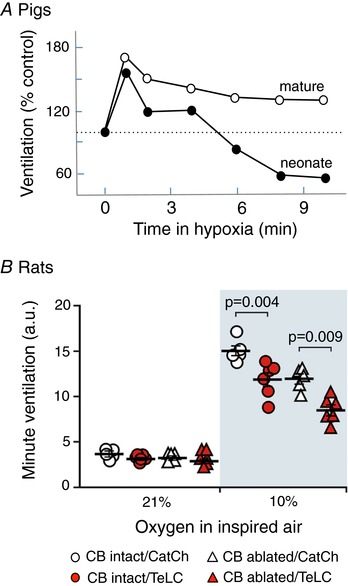

The high‐energy demands of the mammalian brain are met primarily through oxidative metabolism. With minimal capacity for energy storage, the brain depends on a constant supply of oxygen and metabolic substrates to meet these demands. A host of adaptive responses have evolved to protect brain O2 delivery. Prominent among these is the biphasic hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR). The classical view of the HVR is that specialized peripheral chemosensors in the carotid bodies (CBs) (and aortic bodies in some species) detect decreases in the arterial and activate brainstem respiratory centres, causing adaptive increases in ventilation. Ventilation peaks in the first minute and is followed by a secondary hypoxic respiratory depression that is most pronounced in premature mammals and attributed to the central depression of the brainstem respiratory network, decreased CB output or a reduced metabolic rate (Fig. 1 A; Bissonnette, 2000; Teppema & Dahan, 2010). This traditional view posits that the excitatory component of the HVR originates from the CB and that monitoring peripheral arterial is sufficient to ensure brain O2 homeostasis; i.e. the only contribution of the CNS to the HVR is the depression of ventilation. We disagree and here review evidence that the brainstem neuroglial network controlling breathing is specialized through cellular or emergent network properties to orchestrate a homeostatic response to acute hypoxia that includes network excitation and an increase in ventilation that counteracts the hypoxic depression of breathing. Cardiovascular and sympathetic nervous system responses mediated by hypoxia‐sensitive presympathetic neurons (Sun & Reis, 1994), mechanisms of neuronal hypoxia sensing that are not related to the HVR (Haddad & Jiang, 1997), responses to intermittent hypoxia and mechanisms of gasping are beyond the scope of this article.

Figure 1. Attenuation of the hypoxic ventilatory response by disruption of vesicular release mechanisms in preBötC astrocytes.

A, ventilatory responses of young and older (anaesthetized) piglets to hypoxia (6%) (modified with permission from Moss, RA. Respir Physiol (2000) 121, 185–197). B, summary data illustrating hypoxia‐induced changes in minute lung ventilation in carotid body intact and peripherally chemodenervated (10 weeks) conscious rats expressing CatCh (calcium translocating channel rhodopsin variant that was fused with EGFP and used as a control here) or TeLC bilaterally within astrocytes of the preBötC network. Ventilation measurements were obtained during the last 5 min of the 10 min hypoxia period. TeLC caused similar reductions in the HVR of intact and CB‐denervated rats (modified with permission from Angelova et al. 2015).

Maintaining brain metabolic homeostasis is a significant challenge (Marina et al. 2017). O2 profiles vary significantly throughout the brain parenchyma, reflecting complex spatiotemporal differences in local neuronal activities and metabolic demands. These regional differences in brain cannot be detected by the CB chemoreceptors. Neurovascular coupling mechanisms, which do not involve O2 sensing per se, cause changes in regional cerebral blood flow in accordance with changes in neuronal activity that are communicated to the vasculature via astrocytes releasing vasoactive substances (Attwell et al. 2010). Astrocytes are ideally positioned to monitor neuronal activity to adjust blood flow in accordance with local energy demands, but they are equally well‐positioned to modulate neuronal activity in accordance with parenchymal metabolic signals, including brain tissue (Teschemacher et al. 2015). When brain falls acutely, the predominant neurochemical response is an increase in extracellular adenosine, synaptic depression and decreased neuronal activity (Lipton, 1999; Ramirez et al. 2007; Mukandala et al. 2016). This response is adaptive at a local level, as it reduces metabolic demands, enhancing the capacity of brain tissue to survive periods of limited O2 supply, but hypoxic depression of respiratory network activity is maladaptive; i.e. ventilation and sympathetic activity must increase to ensure recovery. There is significant evidence that the brainstem respiratory network can mount an adaptive excitatory response to hypoxia, independent of CB activity.

The literature describing the expression of the HVR after CB denervation (or silencing) is confusing. The majority of mammalian studies show that hypoxia‐induced increases in ventilation are abolished following acute CB denervation (Bissonnette, 2000; Teppema & Dahan, 2010). However, we argue that data interpretation is confounded by the inhibitory effects of anaesthesia on central hypoxia‐sensing mechanisms, and incomplete understanding of how central and peripheral chemosensory inputs are integrated (Smith et al. 2010; Gourine & Funk, 2017). CB denervation could also have an impact on other mechanisms that minimize brain hypoxaemia (e.g. increases in cerebral blood flow and arterial blood pressure, hypometabolism), such that a specific hypoxic stimulus could produce a lower parenchymal in CB‐denervated compared to intact (control) animals. Direct assessment of brain is needed to resolve the significance of this issue. Nevertheless, when allowed to recover from CB denervation and studied without anaesthetic, mice (Soliz et al. 2005), rats (Martin‐Body et al. 1986; Roux et al. 2000; Angelova et al. 2015), cats (Miller & Tenney, 1975; Gautier & Bonora, 1980), dogs (Davenport et al. 1947), goats (Daristotle et al. 1991) and ponies (Bisgard et al. 1976) show partial or almost complete recovery of the HVR. This might reflect compensatory plasticity of non‐CB peripheral chemoreceptors (Hodges & Forster, 2012), or recovery from the disruption of brainstem chemosensory/respiratory network excitability following CB denervation. The latter is supported by experiments in unanaesthetized dogs (Curran et al. 2000) and goats (Daristotle et al. 1991) with intact, isolated and separately perfused CBs. Animals responded to central hypoxia with an increase in ventilation, but denervation of the normoxic/normocapnic CBs abolished/attenuated the ventilatory response to central hypoxia, suggesting that brain O2 sensing mechanisms require permissive/facilitatory inputs from the periphery.

In humans, CB denervation consistently abolishes the HVR (Timmers et al. 2003b; Teppema & Dahan, 2010), but again data interpretation is challenging. Denervation studies commonly involve subjects with chronic lung disease who may have altered chemoreflex function. Thus, it may be significant that some CB‐denervated individuals (2/8) without a history of lung disease showed a HVR under hypercapnic conditions (Timmers et al. 2003a). CB‐resected asthma subjects showed a similar dependence of the HVR on systemic hypercapnia (Swanson et al. 1978), possibly suggesting an interaction between a central hypoxia‐sensitive mechanism and other chemosensory inputs (Gourine & Funk, 2017). Finally, failure to record an increase in ventilation in response to hypoxia does not exclude the existence of a centrally mediated excitatory HVR. Maintenance of ventilation during hypoxia (i.e. no depression) following chronic CB denervation (Swanson et al. 1978) may be evidence of an excitatory HVR.

Brainstem astrocytes (especially those in the preBötzinger complex; preBötC) are emerging as important in coordinating the central component of the HVR. A key observation in anaesthetized rats was the slow‐onset release of the gliotransmitter ATP from the ventral surface of the medulla oblongata during hypoxia (Gourine et al. 2005). A reduction of the steady‐state component of the HVR following microinjections of P2 receptor antagonists into the preBötC (Gourine et al. 2005; Rajani et al. 2018) led to the hypothesis that hypoxia evokes ATP release from astrocytes, which stimulates breathing and attenuates the hypoxic respiratory depression (Gourine et al. 2005). Consistent with this, astrocytes cultured from the brainstem respond to physiologically relevant levels of hypoxia with an increase in [Ca2+]i and vesicular release of ATP (Angelova et al. 2015). Astrocytes are known to change their properties in culture, but accumulating evidence supports the physiological relevance of these observations. First, the HVR is reduced in anaesthetized, mechanically‐ventilated, neuromuscularly blocked rats following unilateral pharmacological inhibition of P2Y1 receptors in the preBötC (Gourine et al. 2005; Rajani et al. 2018), and in CB‐denervated awake rats in conditions of virally induced expression of transmembrane prostatic acid phosphatase (TMPAP) in the preBötC to facilitate rapid degradation of extracellular ATP (Angelova et al. 2015; Sheikhbahaei et al. 2018). Second, viral approaches that expressed the light chain of tetanus toxin (TeLC) or dnSNARE to disrupt vesicular release mechanisms selectively in preBötC astrocytes reduced the HVR in (i) anaesthetized rats; (ii) awake CB‐denervated rats; and (iii) most importantly, awake rats with intact peripheral chemoreceptors, as this addressed the potentially confounding effects of anaesthesia and removal of "permissive" CB input (Fig 1B; Angelova et al. 2015; Rajani et al. 2018; Sheikhbahaei et al. 2018). It will be important to demonstrate that the reduced HVR following TeLC or dnSNARE expression in preBötC astrocytes is not due to non‐specific disruption of glial function and impaired ability of the preBötC to increase ventilation. However, this possibility is unlikely because TeLC and dnSNARE expression specifically target astrocytic vesicular release mechanisms. They do not severely disrupt baseline breathing as might be expected if the general housekeeping functions of astrocytes were impaired. In addition, the HVR is also reduced via manipulations of P2 receptor signalling that have minimal effect on glial function (Angelova et al. 2015; Rajani et al. 2018).

Whether the hypoxia‐induced ATP release by astrocytes and local network excitation is unique to the preBötC is not known. Astrocytes in other areas of the brain respond to hypoxia with increases in [Ca2+]i (Angelova et al. 2015), but purinergic signalling in the preBötC (which is determined by local P2 and P1 receptors, ectonucleotidase activity and a host of transporters and intracellular enzymes that interact to determine the extracellular profile of P2/P1 receptor ligands) may be uniquely organized to favour network excitation.

While many mechanistic details remain unresolved, the (partial) recovery of the HVR in unanaesthetized CB‐denervated mammals, the hypoxia‐evoked release of ATP by brainstem astrocytes and the reduction in the HVR following disruption of astrocytic signalling in the preBötC of awake, CB‐intact rodents provide strong evidence that the conventional view of the CB as the only hypoxic respiratory chemosensor should be revisited.

Call for comments

Readers are invited to give their views on this and the accompanying CrossTalk articles in this issue by submitting a brief (250 word) comment. Comments may be submitted up to 6 weeks after publication of the article, at which point the discussion will close and the CrossTalk authors will be invited to submit a ‘Last Word’. Please email your comment, including a title and a declaration of interest, to jphysiol@physoc.org. Comments will be moderated and accepted comments will be published online only as ‘supporting information’ to the original debate articles once discussion has closed.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Biographies

Greg Funk received his BSc (Hon) in 1985 and PhD in Zoology in 1990 at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver with Drs W. K. Milsom and J. D. Steeves and postdoctoral training with Dr J. L. Feldman at UCLA (1994). He spent 9 years as Lecturer/Sr Lecturer in the Department of Physiology, University of Auckland, New Zealand, before returning to Canada in 2003. He is currently professor in the Department of Physiology at the University of Alberta (Edmonton, Canada) and Honorary Professor in the Department of Physiology at the University of Auckland (New Zealand), Chair of the American Physiological Society Respiration Section and Editor for The Journal of Physiology and Frontiers in Physiology. His main research interests are in the neuronal and glial modulation of motor control systems, specifically in the context of networks that control breathing.

Alexander Gourine is currently a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow and Professor of Physiology within the Department of Neuroscience, Physiology and Pharmacology, University College London (UCL). He obtained his PhD in the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (Moscow), received postdoctoral training in the US and the UK and joined the UCL Physiology Department in 2006 as Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow. He was awarded the Physiological Society's Wellcome Trust Prize in the year 2004 for his contribution to understanding the mechanisms underlying chemosensory control of breathing. His research focuses on central nervous mechanisms of cardiovascular and respiratory control and mechanisms underlying metabolic control of cerebral blood flow.

Edited by: Francisco Sepúlveda & Frank Powell

Linked articles This article is part of a CrossTalk debate. Click the links to read the other articles in this debate: https://doi.org/10.1113/JP276282, https://doi.org/10.1113/JP276281 and https://doi.org/10.1113/JP275708.

References

- Angelova PR, Kasymov V, Christie I, Sheikhbahaei S, Turovsky E, Marina N, Korsak A, Zwicker J, Teschemacher AG, Ackland GL, Funk GD, Kasparov S, Abramov AY & Gourine AV (2015). Functional oxygen sensitivity of astrocytes. J Neurosci 35, 10460–10473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Buchan AM, Charpak S, Lauritzen M, Macvicar BA & Newman EA (2010). Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature 468, 232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgard GE, Forster HV, Orr JA, Buss DD, Rawlings CA & Rasmussen B (1976). Hypoventilation in ponies after carotid body denervation. J Appl Physiol 40, 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette JM ( 2000). Mechanisms regulating hypoxic respiratory depression during fetal and postnatal life. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278, R1391–R1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran AK, Rodman JR, Eastwood PR, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA & Smith CA (2000). Ventilatory responses to specific CNS hypoxia in sleeping dogs. J Appl Physiol 88, 1840–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daristotle L, Engwall MJ, Niu WZ & Bisgard GE (1991). Ventilatory effects and interactions with change in PaO2 in awake goats. J Appl Physiol 71, 1254–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport HW, Brewer G, Chambers AH & Goldschmidt S (1947). The respiratory responses to anoxemia of unanesthetized dogs with chronically denervated aortic and carotid chemoreceptors and their causes. Am J Physiol 148, 406–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier H & Bonora M (1980). Possible alterations in brain monoamine metabolism during hypoxia‐induced tachypnea in cats. J Appl Physiol 49, 769–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV & Funk GD (2017). On the existence of a central respiratory oxygen sensor. J Appl Physiol 123, 1344–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV, Llaudet E, Dale N & Spyer KM (2005). Release of ATP in the ventral medulla during hypoxia in rats: role in hypoxic ventilatory response. J Neurosci 25, 1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad GG & Jiang C (1997). O2‐sensing mechanisms in excitable cells: role of plasma membrane K+ channels. Annu Rev Physiol 59, 23–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR & Forster HV (2012). Respiratory neuroplasticity following carotid body denervation: Central and peripheral adaptations. Neural Regen Res 7, 1073–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P ( 1999). Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol Rev 79, 1431–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marina N, Turovsky E, Christie IN, Hosford PS, Hadjihambi A, Korsak A, Ang R, Mastitskaya S, Sheikhbahaei S, Theparambil SM & Gourine AV (2017). Brain metabolic sensing and metabolic signaling at the level of an astrocyte. Glia 66, 1185–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin‐Body RL, Robson GJ & Sinclair JD (1986). Restoration of hypoxic respiratory responses in the awake rat after carotid body denervation by sinus nerve section. J Physiol 380, 61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ & Tenney SM (1975). Hypoxia‐induced tachypnea in carotid‐deafferented cats. Respir Physiol 23, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukandala G, Tynan R, Lanigan S & O'Connor JJ (2016). The effects of hypoxia and inflammation on synaptic signaling in the CNS. Brain Sci 6, E6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajani R, Zhang Y, Jalubula V, Rancic V, SheikhBahaei S, Zwicker J, Pagliardini S, Dickson C, Ballanyi K, Kasparov S, Gourine AV & Funk GD (2018). Release of ATP by pre‐Bötzinger complex astrocytes contributes to the hypoxic ventilatory response via a Ca2+‐dependent P2Y1 receptor mechanism. J Physiol 596, 3245–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JM, Folkow LP & Blix AS (2007). Hypoxia tolerance in mammals and birds: from the wilderness to the clinic. Annu Rev Physiol 69, 113–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux JC, Pequignot JM, Dumas S, Pascual O, Ghilini G, Pequignot J, Mallet J & Denavit‐Saubie M (2000). O2‐sensing after carotid chemodenervation: hypoxic ventilatory responsiveness and upregulation of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in brainstem catecholaminergic cells. Eur J Neurosci 12, 3181–3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhbahaei S, Turovsky EA, Hosford PS, Hadjihambi A, Theparambil SM, Liu B, Marina N, Teschemacher AG, Kasparov S, Smith JC & Gourine AV (2018). Astrocytes modulate brainstem respiratory rhythm‐generating circuits and determine exercise capacity. Nat Commun 9, 370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Forster HV, Blain GM & Dempsey JA (2010). An interdependent model of central/peripheral chemoreception: evidence and implications for ventilatory control. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 173, 288–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliz J, Joseph V, Soulage C, Becskei C, Vogel J, Pequignot JM, Ogunshola O & Gassmann M (2005). Erythropoietin regulates hypoxic ventilation in mice by interacting with brainstem and carotid bodies. J Physiol 568, 559–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun MK & Reis DJ (1994). Hypoxia selectively excites vasomotor neurons of rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. Am J Physiol 266, R245–R256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson GD, Whipp BJ, Kaufman RD, Aqleh KA, Winter B & Bellville JW (1978). Effect of hypercapnia on hypoxic ventilatory drive in carotid body‐resected man. J Appl Physiol 45, 871–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teppema LJ & Dahan A (2010). The ventilatory response to hypoxia in mammals: mechanisms, measurement, and analysis. Physiol Rev 90, 675–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teschemacher AG, Gourine AV & Kasparov S (2015). A role for astrocytes in sensing the brain microenvironment and neuro‐metabolic integration. Neurochem Res 40, 2386–2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers HJ, Karemaker JM, Wieling W, Marres HA, Folgering HT & Lenders JW (2003a). Baroreflex and chemoreflex function after bilateral carotid body tumor resection. J Hypertens 21, 591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers HJ, Wieling W, Karemaker JM & Lenders JW (2003b). Denervation of carotid baroand chemoreceptors in humans. J Physiol 553, 3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]