Abstract

A 12-year-old intact male Welsh Corgi was presented with enlargement of the right scrotum. Both testicles were surgically removed and histopathologically examined. On gross examination, white nodules were found in the epididymis and ductus deferens. Histopathologically, the nodules developed continuously from the tunica vaginalis testis of the right scrotum and consisted of spindle-shaped neoplastic cells that invaded the surrounding tissue. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for vimentin, cytokeratin and Wilms tumor-1 (WT-1). Based on these findings, the tumor was diagnosed as sarcomatoid mesothelioma. The dog presented with respiratory distress 122 days after surgery and clinical examination found multiple metastatic lesions in the lung, abdominal lymph nodes and peritoneum. The dog died 144 days after surgery due to disease progression.

Keywords: dog, immunohistochemistry, sarcomatoid mesothelioma, tunica vaginalis

Mesothelioma is a rare tumor arising from mesoderm-derived mesothelial cells of the serosal surface. In human, it most commonly develops in the pericardial pleural and peritoneal cavities and less commonly in the tunica vaginalis of the testis [14, 16]. Several studies have reported canine mesotheliomas arising in the pleura, peritoneum and pericardium [7, 8, 15, 19], although there are only two cases of mesothelioma arising in the tunica vaginalis testis in the dog [3, 18]. In the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of human [6] and domestic animals [9], mesothelioma has been classified into epithelioid, sarcomatoid (fibrous, sarcomatous) and biphasic (mixed) subtypes, depending on predominant epithelioid and/or spindle-shaped mesothelial cell component. The present study describes the clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical features of sarcomatoid mesothelioma in the tunica vaginalis testis of a dog.

A 12-year-old intact male Welsh Corgi dog was brought to the Veterinary Medical Center, the University of Tokyo with the main complaint of an enlarged right scrotum. The dog showed no other specific clinical signs. Blood examination, thoracic and abdominal radiographs, abdominal and scrotal ultrasound, fine needle aspiration of the enlarged scrotum, and subsequent computed tomography (CT) scanning of the whole body were performed. Results of the blood examinations were unremarkable. On ultrasound imaging, a mass lesion was located in the right scrotum continuous to the testis and spermatic cord. There was no specific finding in the left testis. On fine needle aspiration cytology of the mass, a few spindle-shaped atypical cells were observed in small clusters. The cells showed mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. CT scanning revealed a spherical soft tissue mass (7.0 × 4.0 × 3.0 cm) cranial to the testis (Fig. 1a), an enlarged right internal iliac lymph node (0.8 cm) and a solitary nodule (0.2 cm) in the right cranial lobe of the lung. Clinical diagnosis of testicular tumor with possible lymph node and pulmonary metastasis was made.

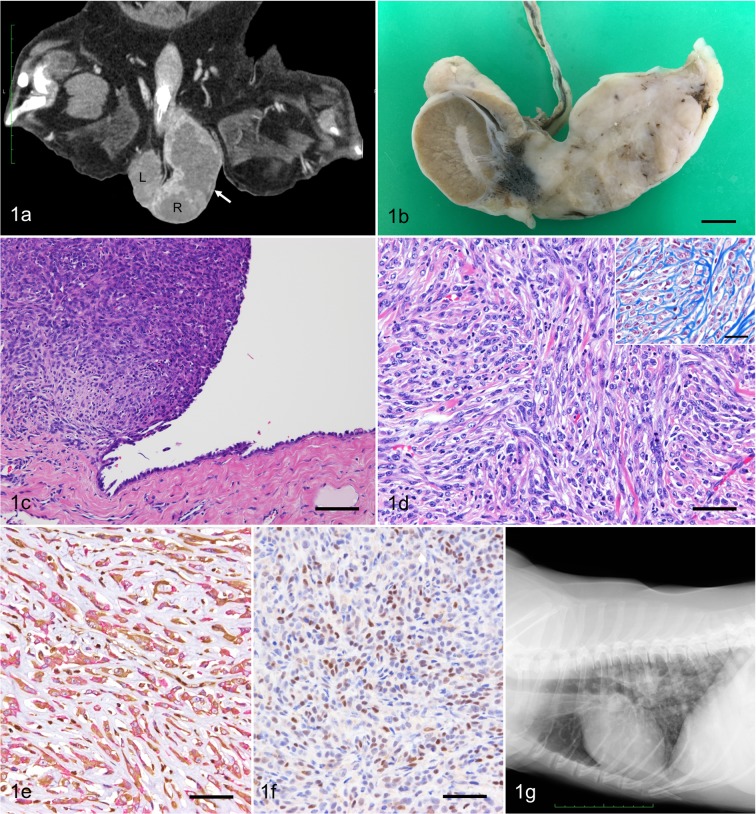

Fig. 1.

(a) Dorsoventral CT view of the scrotum. A mass (7.0 × 4.0 × 3.0 cm, arrow) locates cranial to the right testis (R) in the scrotum. The left testis (L) is intact. (b) Gross appearance of the right testis cut surface shows a white solid mass infiltrating the head of epididymis. Bar=1 cm. (c) The mass is continuous to the mesothelium of the tunica vaginalis testis. HE. Bar=100 µm. (d) Neoplastic cells are spindle-shaped with round to elongate nuclei and scant cytoplasm. HE. Bar=50 µm. Bundles of collagen separates neoplastic cells (inset). Masson’s trichrome stain. Bar=25 µm. (e) The cytoplasm of the tumor cells are positive for both vimentin (brown) and cytokeratin (red). Double immunohistochemistry. Bar=50 µm. (f) Nuclei of the tumor cells are positive for WT-1. Immunohistochemistry. Bar=50 µm. (g) Thoracic radiograph shows multiple nodular lesions with variable size in the lung.

Five days after initial presentation, bilateral orchiectomy was performed for difinitive diagnosis and local control of the desease. With a routine approach, the right testicle and mass were removed en bloc. Since possible invasive lesions of the tumor (i.e. multiple white small nodule inside the spermatic cord along the testicular vessels) were observed during surgery, the right spermatic cord was isolated as long as possible toward the inguinal ring and dissected at macroscopically intact site. Postoperative recovery was uneventful. Resected tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and then embedded in paraffin wax. Sections (4 µm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and Masson’s trichrome. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the EnVision+System horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled polymer (Dako, Tokyo, Japan). For double immunohistochemistry, first, the sections were incubated with anti-vimentin antibody and then visualized with 3, 3′ diaminobenzidine chromogen (Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan). Next, the slides were incubated with anti-cytokeratin antibody (AE1/AE3) and then visualized with New fuchsin chromogen (Nichirei Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and finally counterstained with hematoxylin. Primary antibodies used, dilution and antigen retrieval methods are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Primary antibodies and protocols for immunohistochemistry.

| Antibody | Host (Clone) | Dilution | Pre-treatment | Manufacturer | Normal mesothelial cell | Tumor cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokeratin | Mouse (AE1/AE3) | RTU | pH 6.0 AC | Dako (Tokyo, Japan) | + | + |

| Vimentin | Mouse (V9) | RTU | pH 6.0 AC | Dako (Tokyo, Japan) | + | + |

| CEA | Rabbit | 1:400 | pH 6.0 AC | Dako (Tokyo, Japan) | - | - |

| Mesothelial cells | Mouse (HBME-1) | 1:50 | None | Dako (Tokyo, Japan) | + | - |

| WT-1 | Rabbit | 1:100 | pH 6.0 AC | Acris (Herford, Germany) | + | + |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; WT-1, Wilms tumor-1; RTU, ready-to-use; AC, autoclaved; +, positive; -, negative.

Gross examination of the cut surface of the right testicle revealed a white mass approximately 5.5 cm in diameter attached to the tunica vaginalis and infiltrating the head of epididymis (Fig. 1b). Also, multifocal nodules 0.5–1.0 cm in diameter, were observed in the epididymis and ductus deferens, but not in the testis.

Histopathologically, the unencapsulated nodular mass in the right testicle had continuity with the mesothelium of the tunica vaginalis testis and was composed of neoplastic spindle cells (Fig. 1c). Tumor cells showed invasive growth and were arranged in a wavy pattern with various amounts of interstitial collagen (Fig. 1d). Tumor cells had round to elongate nuclei with fine chromatin, and scant cytoplasm. Tumor cells exhibited a high degree of anisokaryosis and anisocytosis. The number of mitotic figures of tumor cells was less than one per high power field. Tumor tissue infiltrated the mediastinum testis and the epididymis. In addtion, tumor tissue was observed at the excision margin of spermatic cord. No significant change was observed in the left testis.

Immunohistochemically, the cytoplasm of the tumor cells were positive for both vimentin and cytokeratin (Fig. 1e). The nuclei of normal mesothelial cells and approximately 54% of the nuclei of neoplastic cells were positive for Wilms tumor-1 (WT-1) (Fig. 1f). The tumor cells were negative for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and Hector Bartifora mesothelial epitope-1 (HBME-1), whereas the cells lining the normal tunica vaginalis serous were positive for HBME-1 and negative for CEA. Based on the gross, histopathological and immunohistochemical findings, the lesion was diagnosed as sarcomatoid mesothelioma.

Further adjunctive treatments such as chemotherapy were not performed. One month after surgery, swelling of the right internal iliac lymph node (2.5 × 2.0 cm) was noticed on ultrasound. Four months after surgery, the dog presented with respiratory distress and anorexia. A thoracic radiograph revealed multiple nodular lesions in the lung without evidence of pleural effusion (Fig. 1g). A large number of abdominal lymph node metastases were suspected by the ultrasound examination. Systemic metastases of malignant mesothelioma was suspected. The dog died 144 days after surgery, however, necropsy was not performed.

Mesothelioma is a malignant neoplasm of the serous membrane and have been reported in a bull, horses, cats and dogs [3, 7,8,9, 15, 17,18,19]. The tunica vaginalis of the testis is formed by an outpouching of the abdominal peritoneum, and has been one of the uncommon sites of mesothelioma. Histologically, mesothelioma can be classified into three subtypes: epithelioid, sarcomatoid (fibrous, sarcomatous), and biphasic (mixed) [6, 9]. In previous reports on mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis testis in two dogs, the neoplastic cells were of epithelial type and were arranged in tubulopapillary pattern [3] or tubular pattern [18]. In a case report of a bull, the neoplastic cells were of biphasic (mixed) type with both epithelial and sarcomatous components [17]. In the present case, neoplastic cells were predominantly spindle-shaped and thus classified as sarcomatoid mesothelioma.

In addition to the location and the morphology of the tumor, immunohistochemistry is an important adjunct to the diagnosis of mesothelioma. As reported in previous cases of mesothelioma of animals, the neoplastic cells in the present case were positive both for cytokeratin and vimentin [9, 15, 18, 19]. CEA, which was negative in the present case, had been used to differentiate mesothelioma from other epithelial tumors in a canine case [19]. HBME-1 is expressed in neoplastic cells of epithelial mesothelioma such as in previous canine cases of mesothelioma of tunica vaginalis as well as in normal mesothelial cells [4, 18]. In the present case, sarcomatous tumor cells were negative for HBME-1, which may be associated with the different histological subtype [1]. WT-1 is known to play a crucial role in the mesenchymal−epithelial transition of cells [12]. Human mesothelioma cells are positive for WT-1, but cells of primary lung tumors and pleural metastatic lesions of breast and colon adenocarcinomas are negative [6, 10]. Thus WT-1 is suggested as a marker for mesothelioma. However, in human, WT-1 expression of sarcomatoid mesothelioma is considerably lower than that of epitheloid mesothelioma [13]. The percentage of WT-1 positive cases with sarcomatoid mesothelioma range from less than 20 to 89.7% [2, 11, 13]. In animals, tumor cells of canine peritoneal mesothelioma were weakly to strongly positive for WT-1 [5, 15]. Sarcoma and metastatic sarcomatoid carcinoma are differential diagnoses for the present case, however these were ruled out based on the continuous growth of the tumor from the tunica vaginalis testis and the immunohistochemical results for cytokeratin, vimentin and WT-1 [9, 15, 18].

The survival time of this case was 144 days after surgery. The prognosis of the previously reported canine cases of mesothelioma in the tunica vaginalis of the testis were also guarded with survival time of 3 and 4 months due to progression with peritoneal and mesenteric metastases [3, 18]. Therefore, mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis of the testis is likely to be a progressive disease with systemic metastatic lesions. No adjuvant therapy was performed in the 3 dogs including this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of sarcomatoid mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis testis in the dog. In addition, WT-1 may be a potential marker for the immunohistochemical diagnosis of canine mesothelioma.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. S. Kato for her technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Attanoos R. L., Webb R., Dojcinov S. D., Gibbs A. R.2001. Malignant epithelioid mesothelioma: anti-mesothelial marker expression correlates with histological pattern. Histopathology 39: 584–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirieac L. R., Pinkus G. S., Pinkus J. L., Godleski J., Sugarbaker D. J., Corson J. M.2011. The immunohistochemical characterization of sarcomatoid malignant mesothelioma of the pleura. Am. J. Cancer Res. 1: 14–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cihak R. W., Roen D. R., Klaassen J.1986. Malignant mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis in a dog. J. Comp. Pathol. 96: 459–462. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(86)90041-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlstrom J. E., Maxwell L. E., Brodie N., Zardawi I. M., Jain S.2001. Distinctive microvillous brush border staining with HBME-1 distinguishes pleural mesotheliomas from pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Pathology 33: 287–291. doi: 10.1080/00313020126322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Angelo A. R., Di Francesco G.2014. Sclerosing peritoneal mesothelioma in a dog: histopathological, histochemical and immunohistochemical investigations. Vet. Ital. 50: 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galateau-Salle F., Churg A., Roggli V., Travis W. D., World Health Organization Committee for Tumors of the Pleura. 2016. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Pleura: Advances since the 2004 Classification. J. Thorac. Oncol. 11: 142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glickman L. T., Domanski L. M., Maguire T. G., Dubielzig R. R., Churg A.1983. Mesothelioma in pet dogs associated with exposure of their owners to asbestos. Environ. Res. 32: 305–313. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(83)90114-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harbison M. L., Godleski J. J.1983. Malignant mesothelioma in urban dogs. Vet. Pathol. 20: 531–540. doi: 10.1177/030098588302000504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Head K. W., Cullen J. M., Dubielzig R. R., Else R. W., Misdorp W., Patnaik A. K., Tateyama S., Van der Gaag I.2003. Tumors of serosal surfaces (pleura, pericardium, peritoneum and tunica vaginalis). pp. 144–147. In: Histological Classification of Tumors of the Alimentary System of Domestic Animals, (Schulman, F. Y. ed.), Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar-Singh S., Segers K., Rodeck U., Backhovens H., Bogers J., Weyler J., Van Broeckhoven C., Van Marck E.1997. WT1 mutation in malignant mesothelioma and WT1 immunoreactivity in relation to p53 and growth factor receptor expression, cell-type transition, and prognosis. J. Pathol. 181: 67–74. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushitani K., Takeshima Y., Amatya V. J., Furonaka O., Sakatani A., Inai K.2008. Differential diagnosis of sarcomatoid mesothelioma from true sarcoma and sarcomatoid carcinoma using immunohistochemistry. Pathol. Int. 58: 75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langerak A. W., Williamson K. A., Miyagawa K., Hagemeijer A., Versnel M. A., Hastie N. D.1995. Expression of the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in human malignant mesothelioma cell lines and relationship to platelet-derived growth factor A and insulin-like growth factor 2 expression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 12: 87–96. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870120203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marchevsky A. M.2008. Application of immunohistochemistry to the diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 132: 397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plas E., Riedl C. R., Pflüger H.1998. Malignant mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis testis: review of the literature and assessment of prognostic parameters. Cancer 83: 2437–2446. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato T., Miyoshi T., Shibuya H., Fujikura J., Koie H., Miyazaki Y.2005. Peritoneal biphasic mesothelioma in a dog. J. Vet. Med. A Physiol. Pathol. Clin. Med. 52: 22–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.2004.00680.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimada S., Ono K., Suzuki Y., Mori N.2004. Malignant mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis testis: a case with a predominant sarcomatous component. Pathol. Int. 54: 930–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton R. H.1988. Mesothelioma in the tunica vaginalis of a bull. J. Comp. Pathol. 99: 78–82. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(88)90106-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vascellari M., Carminato A., Camali G., Melchiotti E., Mutinelli F.2011. Malignant mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis testis in a dog: histological and immunohistochemical characterization. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 23: 135–139. doi: 10.1177/104063871102300125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vural S. A., Ozyildiz Z., Ozsoy S. Y.2007. Pleural mesothelioma in a nine-month-old dog. Ir. Vet. J. 60: 30–33. doi: 10.1186/2046-0481-60-1-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]