Abstract

The life expectancy provides valuable information about population health. The life expectancies were evaluated in 12,039 dogs which were buried or cremated during January 2012 to March 2015. The data of dogs were collected at the eight animal cemeteries in Tokyo. The overall life expectancy of dogs was 13.7 (95% confidence interval (CI): 13.7–13.8) years. The probability of death was high in the first year of life, lowest in the fourth year, and increased exponentially after four years of age like Gompertz curve in semilog graph. The life expectancy of companion dogs in Tokyo has increased 1.67 fold from 8.6 years to 13.7 years over the past three decades. Canine crossbreed life expectancy (15.1 years, 95% CI 14.9–15.3) was significantly greater than pure breed life expectancy (13.6 years, 95%CI 13.5–13.7, P-value <0.001). The life expectancy for male and for female dogs were 13.6 (95% CI: 13.5–13.7) and 13.5 (95% CI: 13.4–13.6) years, respectively, with no significant difference (P=0.097). In terms of the median age of death and life expectancy for major breeds, Shiba had the highest median age of death (15.7 years), life expectancy (15.5 years) and French Bulldog had the lowest median age of death (10.2 years), life expectancy (10.2 years). When considering life expectancy alone, these results suggest that the health of companion dogs in Japan has significantly improved over the past 30 years.

Keywords: dog, Japan, life expectancy, pet cemetery data

Dogs are the most popular companion animal in Japan with a population estimated to be 9.9 million in October 2016, and with 14.2% of households owning one or more dogs as companion animals [9]. An increasing number of dogs in Japan apparently enjoy improved health than hitherto partly due to the use of commercial pet food and partly to veterinary medical care [11]. As a result, their life expectancy is expected to have been extended in recent years.

The estimate of life expectancy provides valuable information about the health and nutritional status of companion animals in a specific group. Although there have been many studies estimating the longevity of dogs, most of these studies used the median age as indicator of longevity [14, 16], due to the sample sizes used not being large enough to construct a life table. A relatively large sample of dying dogs is needed to construct a life table, reflecting the ages of all dying individual dogs, and thereby to estimate the average life expectancy by age, sex and breed. Life table is defined as a valuable analytical tool to summarize the mortality experience of the current population and to study longevity [1].

There are two principal forms of the life table: the cohort (or generation) life table and the current life table. The cohort life table records the actual mortality experience of a particular group of individuals (the cohort) over its entire lifetime. The current life table gives a cross-sectional view of the mortality and survival experience of a population during a current year and is dependent on the age-specific death rates prevailing in the year for which it is constructed [1].

Previously, Hayashidani et al. [6] conducted a study to estimate the life expectancy of dogs in Japan using pet cemetery data from 1981 to 1982, constructed a cohort life table and estimated the life expectancy of dogs to be 8.3 years at birth (age zero) and 8.6 years at one year old (age one). Inoue et al. [7] constructed a current life table for insured dogs from 2010 to 2011 and estimated their life expectancy to be 13.7 years at birth. The results of these studies were not comparable because of the different types of life table and data source. The data based on the cemeteries was biased in the region (only in Tokyo) and the data based on the insurance was biased in age, breed, urban/rural areas and accessibility to medical care.

The purpose of this study was to estimate the life expectancy of companion dogs in Japan by constructing a cohort life table and median, minimum and maximum age at death using data collected at animal cemeteries in Tokyo, and to compare the longevity with previous study in Japan. We also calculated the proportional mortality by month and season.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection

Data on 12,039 dogs which were buried or cremated during January 2012 to March 2015 were collected at the eight animal cemeteries which were members of the Tokyo Society of Pet Cemeteries (under the auspice of Tokyo Metropolitan Veterinary Medical Association). Information on the dog’s sex, breed, age (in years and in months) and month of death were collected by face-to-face interview with the owner or the person who brought the dog to the cemetery using a standardized questionnaire. Data was not available on whether or not the dogs were naturally deceased or euthanised. In cases where the owner or the person was unable to remember the dog’s exact age in months and only able to remember the age rounded down in years, a random number between 0 and 11 was generated and added to the age stated to compute the dog’s age in months (n=4,230).

Construction of life table

We assumed that the 12,039 dogs included in the current study as a cohort and constructed a cohort life table using the method described in Chiang [1]. In constructing the life table, we used an age interval of one year (x, x+1). The basic variables involved in a cohort life table are lx, the number living at age x and dx, the number dying in the age interval (x, x+1). We calculated the probability of a dog dying in age interval (x, x+1), as a proportion of dogs that died during this age interval over the dogs alive at age x. . We calculated the fraction of last year of life for age x, áx as the average of the fraction of last year of life for dogs that had died during the interval (x, x+1). We calculated the number of years lived by the total cohort in interval (x, x+1), Lx = (lx–dx)+ax×dx. We calculated total number of years lived beyond age x, Tx as the sum of the number of years lived in each age interval beginning with age x. Tx = Lx + Lx+1 + ··· + Lw, x =0, 1, …, w. We constructed a life table using these vaiables, in accordance with the method described by Chiang [1]. The life expectancy at age was calculated, as the number of years, on the average, yet to be lived by a dog of age x. . We constructed a life table for all breeds and sexes combined and for pure and cross breeds and for different sexes. We calculated the variance (S) and standard error (S.E.) of life expectancy using the method described by Chiang [1]. The significance of difference (diff) of life expectancy between different breed groups and sexes was also tested. The statistics for Z test was calculated by , where and were life expectancy at age 0 of different breed and sexes groups, and S.E. (diff.) was defined as (Chiang, 1984). The threshold of significance was P-value=0.05. The 95% confidence intervals were calculated by .

We also calculated the life expectancy at age 0 for 21 dog breeds whose sample size (n) was larger than 100, as well as their median, minimum and maximum age of death.

Proportional mortality by month and season

The proportional mortality by month was calculated as a proportion of dogs that died in the respective months over the total number of dogs that died. Likewise, the proportional mortality by season was calculated as a proportion of dogs that died in the respective seasons (summer: April to September; winter: October to March). The differences were tested using χ2 test for a single comparison. The 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the formula where is the extimated proportion and n is the sample size for the respective months or seasons.

For all statistical analyses, Excel 14.0 (Microsoft Corporation) was utilized.

RESULTS

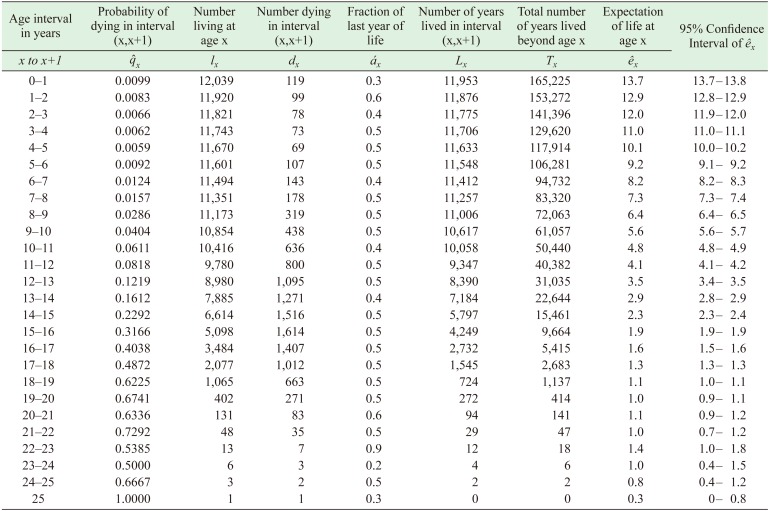

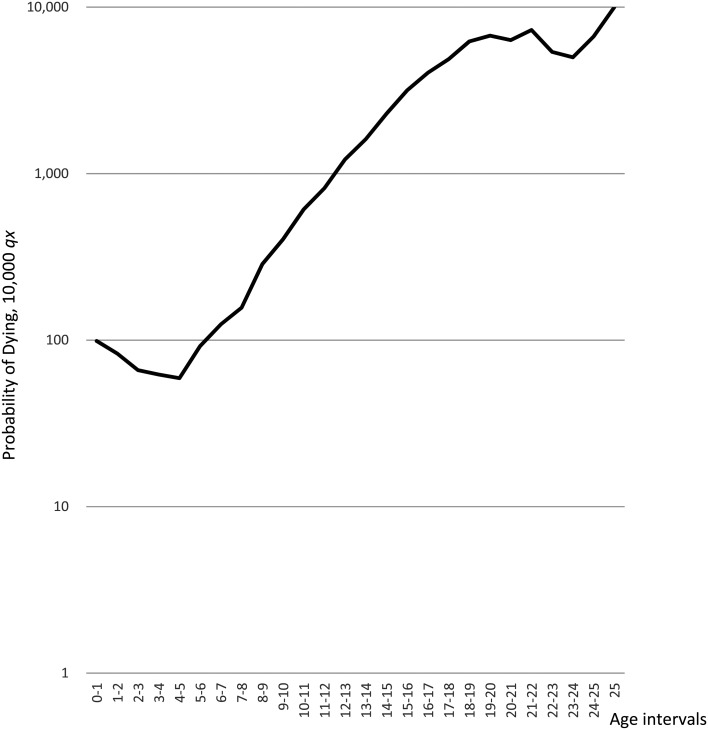

Table 1 shows the cohort life table for all breeds and sexes combined. The probability of death was 0.0099 in the first year of life, and decreased to its lowest in the fourth year of life, and increased like a Gompertz curve after four years old in semilog graph (Fig. 1). The life expectancy at age zero, or the average lifespan was 13.7 (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 13.7–13.8) years. The cross breed had a significantly longer life expectancy (15.1 years, 95% CI: 14.9–15.3) than pure breed (13.6 years, 95%CI:13.5–13.7) (z-test, P-value <0.001, Table 2). The life expectancy for male and for female dogs was 13.6 (95%CI:13.5–13.7) and 13.5 (95%CI: 13.4–13.6) years, respectively, with no significant difference (z-test, P-value=0.097, Table 2).

Table 1. Cohort life table for companion dogs for all breeds and sexes combined.

Fig. 1.

Probability of dying of dogs.

Table 2. Life expectancy of companion dogs by breed and sex.

| Breed/Sex | Number | Expectation of life at age 0 | (95% Confidence Interval) | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 12,039 | 13.7 | (13.7 | – | 13.8) | |

| Breed | ||||||

| Pure Breed | 10,922 | 13.6 | (13.5 | – | 13.7) | <0.00001 |

| Cross Breed | 1,117 | 15.1 | (14.9 | – | 15.3) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 6,189 | 13.6 | (13.5 | – | 13.7) | =0.097 |

| Female | 5,850 | 13.5 | (13.4 | – | 13.6) | |

The median age of death was 14.0 years for all breeds and sexes combined. Shiba had the highest expectation of life at age 0 (15.5 years) and median age of death (15.7 years), and French Bulldog had the lowest expectation of life at age 0 (10.2 years) and median age of death (10.2 years) (Table 3).

Table 3. Expectation of life at age 0, median, minimum and maximum age at death of the companion dogs subjected to the analysis.

| Breeds | Number | Expectation of life at age 0 |

95% Confidence Interval of êx |

Age at death (years) |

Group by body mass a) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Minimum | Maximum | |||||||

| Miniature Dachshund | 1,578 | 13.9 | 13.7 | – | 14.0 | 13.9 | 0.0 | 21.6 | Small |

| Chihuahua | 1,079 | 11.8 | 11.7 | – | 11.9 | 11.8 | 0.0 | 21.7 | Toy |

| Shih Tzu | 962 | 15.0 | 14.8 | – | 15.1 | 14.8 | 0.1 | 20.9 | Small |

| Yorkshire Terrier | 784 | 14.3 | 14.0 | – | 14.5 | 14.5 | 0.0 | 20.3 | Toy |

| Shiba | 614 | 15.5 | 15.3 | – | 15.8 | 15.7 | 0.0 | 25.2 | Medium |

| Toy Poodle | 560 | 12.7 | 12.3 | – | 13.2 | 13.5 | 0.0 | 22.4 | Toy |

| Maltese | 437 | 14.3 | 13.9 | – | 14.6 | 14.5 | 0.0 | 22.8 | Toy |

| Pembroke Welsh Corgi | 405 | 13.5 | 13.3 | – | 13.7 | 13.3 | 0.5 | 18.8 | Medium |

| Pomeranian | 386 | 14.0 | 13.7 | – | 14.4 | 14.3 | 0.2 | 20.7 | Toy |

| Papillon | 382 | 14.4 | 14.1 | – | 14.7 | 14.4 | 0.5 | 23.0 | Small |

| Cross breed (BW >10 kg) | 368 | 15.3 | 15.0 | – | 15.6 | 15.4 | 0.8 | 23.9 | Medium |

| Labrador Retriever | 328 | 14.1 | 13.8 | – | 14.3 | 14.0 | 0.6 | 19.2 | Large |

| Golden Retriever | 295 | 13.1 | 12.8 | – | 13.4 | 12.9 | 0.2 | 18.0 | Large |

| Miniature Schnauzer | 286 | 13.4 | 12.9 | – | 13.8 | 13.2 | 0.1 | 18.3 | Small |

| Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | 251 | 13.1 | 12.7 | – | 13.4 | 13.0 | 0.1 | 18.5 | Small |

| Shetland Sheepdog | 239 | 14.3 | 13.9 | – | 14.6 | 14.1 | 0.8 | 24.1 | Medium |

| Beagle | 205 | 14.8 | 14.4 | – | 15.1 | 14.5 | 3.8 | 20.0 | Medium |

| Pug | 193 | 12.8 | 12.1 | – | 13.4 | 12.6 | 0.2 | 19.0 | Small |

| Cross breed (BW <10 kg) | 182 | 13.3 | 12.5 | – | 14.0 | 14.5 | 0.0 | 21.2 | Small |

| French Bulldog | 151 | 10.2 | 9.7 | – | 10.7 | 10.2 | 0.1 | 15.9 | Medium |

| American Cocker Spaniel | 139 | 12.8 | 12.3 | – | 13.3 | 12.8 | 0.3 | 17.7 | Medium |

| Total | 12,039 | 13.7 | 13.7 | – | 13.8 | 14.0 | 0.0 | 25.2 | |

a) Breeds were classified into five groups of breeds according to their ideal body weights: toy (<5 kg), small (5–10 kg), medium (10−20 kg), large (20−40 kg) and giant (≥40 kg). Data on the ideal weight of each breed were obtained from the Japan Kennel Club (2013).

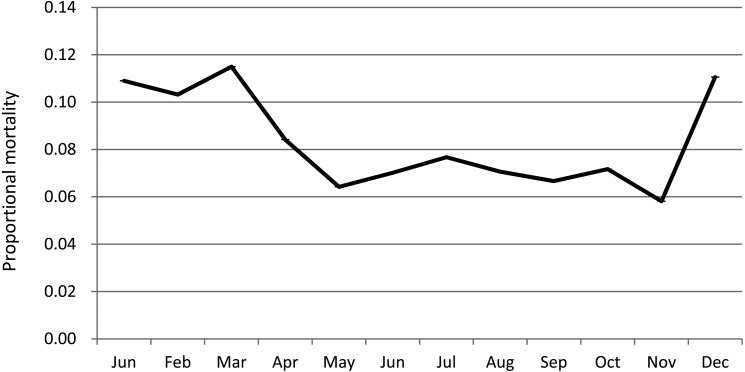

In terms of the month of death, 10.3% of the dogs that died in this study died in February, 7.2% of the dogs died in June, 11.1% of dogs in December (Fig. 2). The proportion of dogs that died in the winter season (October to March) was higher than that of dogs that died in summer season (April to September) with significant difference (χ2, P<0.05).

Fig. 2.

Proportional mortality of dogs by month.

DISCUSSION

We constructed a cohort life table using animal cemetery records in Tokyo, aiming to provide scientific information on the average life expectancy of companion dogs in Japan. The average number of registered companion dogs in Tokyo in 2012–2015 under the Rabies Prevention Law was 516,750 [15]. The sample size of the dogs subjected to the current study represented 2.3% (=12,039/516,750) of the registered companion dog population in Tokyo. To examine how much we can generalize from our data, we compared the dog population brought to the cemeteries with the general dog population in Japan. We examined if the dog population used in our study is representative of the general dog population in terms of breed. According to the result of a survey conducted by the Japan Pet Food Association in 2015, cross breed dogs represent 17.5% of the dog population in Japan [9], while the cross breed dogs represented 9.3% of the dog population used in our study. This indicates that the pure breed dogs might be over-represented in our study, and consequently the overall life expectancy might have been underestimated.

In our study, we estimated an overall life expectancy of 13.7 at age zero, while a previous study by Hayashidani et al. [6] estimated an overall life expectancy of 8.3 and 8.6 years at ages zero and one respectively, by constructing a cohort life table using data of 4,915 dogs brought to a cemetery in Tokyo. Their results showed that the life expectancy at age zero (8.3 years) was lower than that at age one (8.6 years) with the probability of death at age zero (0.15), being higher than that at age one (0.06). This phenomenon, which was not observed in our study, might be attributed to sampling bias as a result of owners’ behavior who seldom buried their dogs at young ages in those years [6]. Moreover, in their study the probability of death at the ages 10, 15 and 20 was relatively high, indicating that the owners most probably rounded up and down the dogs ages as they got older [6]. Despite these differences in data quality and presence of biases in our and their studies, the life expectancy of companion dogs in Tokyo has increased 1.67 fold from 8.6 years to 13.7 years over the past three decades. The leading causes of death for companion dogs in the early 1980s were infectious diseases such as heartworm disease, gastrointestinal nematodiasis and canine distemper, hit-by-car accident and malnutrition [18]. The increased provision of veterinary care and the assumed improved nutrition as a result of increasing use of well-balanced commercial pet food as well as promotion of animal welfare among Japanese people in recent years might have resulted in the extended life expectancy in recent years. In the other study in the UK, the median estimate of 11.1 years from dogs insured and attending dog shows in 1999 [14], the median longevity for dogs of 12.0 years from primary veterinary hospital data in 2013 has reported [16]. These studies showed the longevity of dogs has extended considerably in these countries.

The comparison the life expectancy of common breeds was not enough only using expectation of life at age 0, because the number of each breeds were small to construction life table. So the median ages of death ware used to evaluate longevity with expectation of life at age 0. The result of our study was not consistent with the results of previous studies, which reported that breeds with smaller body mass have greater longevity [12, 13, 17]. Among the eleven dog breeds which had an older expectation of life age at 0 than all breeds combined (13.7 years), there were four medium breeds (Shiba, cross breed with body weight >10 kg, Shetland Sheepdog and Beagle), three small breeds (Miniture Dachshund, Shih Tzu and Papillon), three toy breed (Yorkshire Terrier, maltese and Pomeranian) and one large breed (Labrador Retriever); while among the ten dog breeds which had a younger expectation of life age at 0, there were one large breed (Golden Retriever), three medium breeds (American Cocker Spaniel, Pembroke Welsh Corgi and French Bulldog), four small breeds (Miniature Schnauzer, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Pug and cross breed with body weight <10 kg) and two toy breeds (Chihuahua and Toy Poodle) (Table 3). This suggests that the longevity of dogs might not be directly related to the size of the breed and highlighted the need to analyze life expectancy at individual breed level since there could be certain common diseases affecting a particular breed.

In the present study, Shiba had the oldest age of death (15.7 years) which was even higher than that for cross breeds (BW >10 kg) (15.4 years). According to a recent study using data from insured dogs in Japan [8], the prevalence of dermatological disorders in Shiba was high (mean annual prevalence is 29%), while the prevalence of life threatening diseases such as neoplasia and cardiovascular disorders were relatively low. Moreover, French Bulldog, Golden Retriever, Pug, Chihuahua and Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, which had a relatively low life expectancy based on our results, were all breeds with high risk of neoplasia or cardiovascular disorders [8]. Since dogs appear to display variation in life expectancy and causes of death across individual breeds [4, 16], further research on the genetic factors affecting longevity at individual breed level is highly needed.

Recently, the biology of ageing and social factors influencing longevity have been widely researched [3]. The increasing role of companion dogs as an animal model for researches in geroscience and life extension science has also been highlighted [5]. In terms of the reason of larger dog breeds living shorter, it has been hypothesized that they expend relatively more energy to growth due to slow growth rates and this causes additional base damage to cells as a result of increased oxidative stress [10]. Furthermore, a study on the lifespan of dogs using Rottweiler as a model revealed that the mortality rates of neoplasia for long-living dogs were lower than that for young dogs [2], suggesting that long-living dogs might have genetic resistance against life-threatening diseases. In addition, it has been proposed that companion dogs might have higher risks of neoplasia due to the potential exposure of the carcinogen also affecting humans [19]. Overall, researches on the lifespan and ageing of dogs will help promote the health of companion dogs, thus improving the quality of life of dogs’ owners and also providing important information to benefit human health.

Proportional mortality by month of companion dogs obtained in our study showed that dogs had a higher probability of death during the winter season than summer season. Further studies are needed to identify the risk factors affecting the seasonal mortality.

The current study analyzed the life expectancy of dogs in Japan but not their causes of death. Therefore, further mortality analyses on the causes of death for individual dog breeds at different age intervals are warranted to provide scientific information that will enhance the quality and length of life for companion dogs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tokyo Society of Pet Cemeteries and the Tokyo Veterinary Medical Association for providing us with data of companion dogs for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiang C. L.1984. The Life Table and Its Applications. Robert E. Krieger, Malabar. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooley D. M., Schlittler D. L., Glickman L. T., Hayek M., Waters D. J.2003. Exceptional longevity in pet dogs is accompanied by cancer resistance and delayed onset of major diseases. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 58: B1078–B1084. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.12.B1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creevy K. E., Austad S. N., Hoffman J. M., O’Neill D. G., Promislow D. E.2016. The companion dog as a model for the longevity dividend. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6: a026633. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming J. M., Creevy K. E., Promislow D. E. L.2011. Mortality in north american dogs from 1984 to 2004: an investigation into age-, size-, and breed-related causes of death. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 25: 187–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimm D.2015. Why we outlive our pets. Science 350: 1182–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.350.6265.1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayashidani H., Omi Y., Ogawa M., Fukutomi K.1988. Epidemiological studies on the expectation of life for dogs computed from animal cemetery records. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi 50: 1003–1008. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.50.1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue M., Hasegawa A., Hosoi Y., Sugiura K.2015. A current life table and causes of death for insured dogs in Japan. Prev. Vet. Med. 120: 210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue M., Hasegawa A., Hosoi Y., Sugiura K.2015. Breed, gender and age pattern of diagnosis for veterinary care in insured dogs in Japan during fiscal year 2010. Prev. Vet. Med. 119: 54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Japan Pet Food Association. 2016. Research for the number of household dog and cats in Japan. http://www.petfood.or.jp/data/chart2015/index.html [accessed on May 16, 2018].

- 10.Jimenez A. G.2016. Physiological underpinnings in life-history trade-offs in man’s most popular selection experiment: the dog. J. Comp. Physiol. B 186: 813–827. doi: 10.1007/s00360-016-1002-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kido S., Hayashidani H., Iwasaki K., Okatani A. T., Kaneko K., Ogawa M., 2001. Epidemiological analysis of the factors associated with the longevity of dogs and cats. J. Vet. Epidemiol. 5:77–87. doi: 10.2743/jve.5.77 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraus C., Pavard S., Promislow D. E.2013. The size-life span trade-off decomposed: why large dogs die young. Am. Nat. 181: 492–505. doi: 10.1086/669665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y., Deeb B., Pendergrass W., Wolf N.1996. Cellular proliferative capacity and life span in small and large dogs. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 51: B403–B408. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51A.6.B403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michell A. R.1999. Longevity of British breeds of dog and its relationships with sex, size, cardiovascular variables and disease. Vet. Rec. 145: 625–629. doi: 10.1136/vr.145.22.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. 2014. Registration number of dogs by prefecture. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou10/01.html [accessed on May 16, 2018].

- 16.O’Neill D. G., Church D. B., McGreevy P. D., Thomson P. C., Brodbelt D. C.2013. Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England. Vet. J. 198: 638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patronek G. J., Waters D. J., Glickman L. T.1997. Comparative longevity of pet dogs and humans: implications for gerontology research. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 52: B171–B178. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52A.3.B171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suda O.2011. To act of aging for dogs and cats in Japan. Nippon Juishikai Zasshi 64: 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waters D. J., Wildasin K.2006. Cancer clues from pet dogs. Sci. Am. 295: 94–101. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1206-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]