Abstract

Background

Histological remission has been proposed as a new treatment goal in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) although no universal definition for microscopic activity exists.

Aim

We evaluated the accuracy of histological activity to predict clinical relapse in UC patients with both clinical and endoscopic remission.

Methods

Asymptomatic UC patients in endoscopic remission (Mayo endoscopic sub-score 0 or 1) undergoing surveillance colonoscopy in two referral hospitals were prospectively recruited. All colonic biopsies were analyzed according to the Geboes’ score (GS) and the presence of basal plasmacytosis (BP).

Results

Ninety-six patients were included (38% women, median (interquartile range) age 50.0 (39.0–58.5) years, median disease duration 12.0 (6.5–19.5) years). Histological activity defined as GS ≥ 2B.1, GS ≥ 3.1, or BP was present in, respectively, 26%, 23% and 12%. Within 12 months from index endoscopy, 23% of the patients presented with clinical relapse. In multivariate analysis, active histological disease was the only risk factor predicting clinical relapse (odds ratio (95% confidence interval) 4.29 (1.55–11.87); p = 0.005 for GS ≥ 2B.1 and 4.31 (1.52–12.21); p = 0.006 for GS ≥ 3.1).

Conclusions

In patients with UC in clinical and endoscopic remission, histological activity is an independent risk factor for clinical relapse. Further prospective studies need to clarify whether treatment optimization is justified in this context.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, histological, remission, activity

Key summary

Established knowledge on this subject: Histological activity has been proposed as a risk of relapse in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients. However, definitions of histological activity vary among these studies.

Significant and/or new findings of this study: Histologically active disease defined by the presence of neutrophils either in the lamina propria or also in the epithelium has a prognostic value in UC patients in clinical and endoscopic remission.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by periods of clinical remission followed by clinical relapse. The main therapeutic objective is to achieve and maintain clinical and endoscopic remission. Patients with mucosal healing (MH) have a better outcome with fewer surgeries, complications and hospitalizations, and an increased quality of life.1–3 Some authors have suggested that ongoing active histological disease among patients in clinical and endoscopic remission is a risk factor for clinical relapse.4–7 Additionally, an increased risk of colorectal neoplasia has been described among patients with microscopic disease activity.8,9 Of note, the correlation between clinical, endoscopic and histological features is clearly suboptimal.10,11 Definitions for active histological disease vary significantly among studies.4–7,12

From a microscopic point of view, the inflammatory infiltrate in UC biopsies is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells (commonly in the basal region of lamina propria and known as basal plasmacytosis (BP)), and a variable number of eosinophils and neutrophils.13,14

Response to therapy is typically a gradual evolution, where histologic changes will normalize only after endoscopic and clinical remission is achieved. Histological normalization includes a progressive resolution of the abscesses and the inflammatory infiltrate, and BP tends to decrease toward normal cellularity.15 There is, however, a considerable proportion of patients (up to 40%) with persisting histological activity despite being in both clinical and endoscopic remission.16

Although active histological disease has been linked to a poor prognosis, there is currently not enough evidence to recommend histological healing as a goal of treatment in patients with UC. Because of the potential risk of adverse events and the increasing costs of intensifying treatment in these patients, it is necessary to clarify the impact of histological activity and to standardize definitions in this context.16

Our objective was therefore to assess the prognostic value of histological activity and BP in patients with UC in both clinical and endoscopic remission. As a secondary objective, we analyzed other possible risk factors of clinical relapse, including biological activity.

Material and methods

Patient population

This was a prospective study in two referral hospitals: University Hospitals of Leuven (Leuven, Belgium) and Bellvitge University Hospital (Barcelona, Spain). We included adult UC patients (≥18 years) in clinical and endoscopic remission who underwent a surveillance colonoscopy between June 2011 and September 2014. UC was diagnosed according to conventional endoscopic and histological criteria.17 Clinical remission was defined as a total Mayo score of 2 points or lower, including stool frequency grade 0–1 and rectal bleeding grade 0.1 Endoscopic remission was defined as a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0 or 1. Exclusion criteria consisted of history of colonic resection, pregnancy, Crohn’s disease, IBD type unclassified, prolonged remission (>10 years) or absence of clinical and/or endoscopic remission including intake of steroids. Clinical and demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics.

| Patients’ characteristics (n = 96) | |

|---|---|

| Female (%) | 37 (38) |

| Median (IQR) age (years) | 50.0 (39.0–58.5) |

| Median (IQR) disease duration (years) | 12.0 (6.5–19.5) |

| UC extensiona: E1/E2/E3 (%) | 14/45/36 (15/47/38) |

| Active smoking (%) | 9 (9) |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis (%) | 8 (8) |

| Medication at moment of endoscopy (%) | |

| Mesalamine | 65 (67) |

| Steroids | 0 (0) |

| Immunosuppressantsb | 20 (21) |

| Anti-tumor necrosis factor4 | 32 (33) |

| Median (IQR) time in clinical remission since last relapse (months) | 27.0 (11.0–70.5) |

| Median (IQR) C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 1.2 (0.6–2.9) |

| Median (IQR) hemoglobin (g/dl) | 14.1 (12.9–15.3) |

| Median (IQR) WBC (109/l) (IQR) | 6.0 (5–7.9) |

| Median (IQR) platelets (109/l) | 251 (208–295) |

| Patients with Mayo endoscopic sub-score grade 0/1 (%) | 63/33 (66/34) |

| Patients with Geboes’ score ≥ 2B.1 (%) | 25 (26) |

| Patients with Geboes’ score ≥ 3.1 (%) | 22 (23) |

| Patients with diffuse/focal basal plasmacytosis (%) | 11 (12) |

UC extension according to Montréal classification (proctitis (E1), left-sided colitis (E2) extensive colitis (E3)). bImmunosuppressants, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine.

IRQ: interquartile range; UC: ulcerative colitis; WBC: white blood cells.

The study was approved by the local ethical committees of both hospitals (Ethical Committee of the University Hospitals of Leuven (B322201213950/ S53684) on March 29, 2012, and the Ethical Committee of Bellvitge University Hospital (PR 181/10) on December 23, 2010), and all patients gave written informed consent. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Histological activity

All patients underwent a surveillance colonoscopy, in most of the cases with chromoendoscopy or narrow banding imaging and in some cases with white-light endoscopy. Histological activity was scored according to the Geboes’ score (GS) by an experienced pathologist (GDH) blinded to the endoscopic data. This score is a comprehensive grading system that evaluates the presence of architectural changes, mononuclear cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, crypt destruction, erosions and ulcerations (Table 2).14 In the line of previous reports,18 histological activity was divided in three subgrades, including normal histology (GS grade 0 to 0.2), quiescent disease (GS grade 0.3 to 2A.3 or 2B.3) and active disease (GS grade 2B.1 or 3.1 to 5.4).

Table 2.

Geboes’ score for the calculation of histological activity with additional data about basal plasmacytosis.

| GRADING | |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Structural (architectural) changes |

| 0.0 | No abnormality |

| 0.1 | Mild abnormality |

| 0.2 | Mild or moderate diffuse or multifocal abnormalities |

| 0.3 | Severe diffuse or multifocal abnormalities |

| Grade 1 | Chronic inflammatory infiltrate |

| 1.0 | No increase |

| 1.1 | Mild but unequivocal increase |

| 1.2 | Moderate increase |

| 1.3 | Marked increase |

| Grade 2A | Eosinophils in the lamina propria |

| 2A.0 | No increase |

| 2A.1 | Mild but unequivocal increase |

| 2A.2 | Moderate increase |

| 2A.3 | Marked increase |

| Grade 2B | Neutrophils in the lamina propria |

| 2B.0 | No increase |

| 2B.1 | Mild but unequivocal increase |

| 2B.2 | Moderate increase |

| 2B.3 | Marked increase |

| Grade 3 | Neutrophils in the epithelium |

| 3.0 | None |

| 3.1 | <5% crypts involved |

| 3.2 | <50% crypts involved |

| 3.3 | >50% crypts involved |

| Grade 4 | Crypt destruction |

| 4.0 | None |

| 4.1 | Probable: local excess of neutrophils in part of crypt |

| 4.2 | Probable: marked attenuation |

| 4.3 | Unequivocal crypt destruction |

| Grade 5 | Erosion or ulceration |

| 5.0 | No erosion, ulceration, or granulation tissue |

| 5.1 | Recovering epithelium + adjacent inflammation |

| 5.2 | Probable erosion: focally stripped |

| 5.3 | Unequivocal erosion |

| 5.4 | Ulcer or granulation tissue |

| Extra | Basal plasmacytosis |

| Absent | |

| Focal basal plasmacytosis | |

| Diffuse basal plasmacytosis |

Because there is no consensus on the cutoff for active disease (GS ≥ 2B.1 or GS ≥ 3.1), we performed the whole analyses with both cutoffs. In addition to the variables included in GS, BP was also evaluated.6 BP was defined as an infiltrate of plasma cells predominantly observed between the base of the crypts and the muscularis mucosae.15

Assessment of the clinical outcome

From the moment of colonoscopy, patients were followed clinically for 12 months to evaluate the occurrence of clinical relapse, UC-related hospitalization, colectomy or death. This information was obtained from electronic clinical records. Clinical relapse was defined as clinical Mayo partial score ≥3 and/or need of introducing steroids or any other treatment escalation.

Clinical evaluation was performed in either the outpatient clinic or telephonically by a physician specializing in IBD.

Statistical analyses

SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for appropriate statistical methods. Descriptive statistics were calculated as percentages for discrete data and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous nonparametric data. Spearman correlation and kappa index between biologic, endoscopic and histologic markers were calculated. Univariate (Chi-square and Mann–Whitney tests) and multiple regression analysis were performed to assess the risk of histology and the other variables as potential risk factors of clinical relapse. Kaplan-Meyer curves were used to analyze the risk of clinical relapse along the follow-up. P values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

A total of 96 patients were included (39 from Bellvitge University Hospital in Barcelona and 57 from University Hospitals Leuven in Leuven). Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Relation between biologic, endoscopic and histological markers

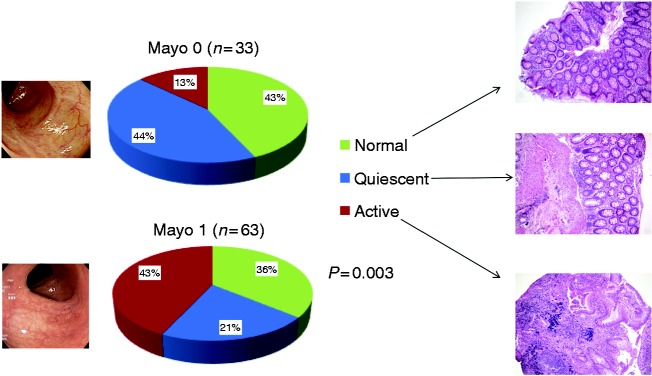

Among the 96 patients, 63 (66%) presented with a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0, and 33 (34%) a sub-score of 1. Regarding histology, 25 (26%) presented with a GS ≥ 2B.1, 22 (23%) presented with a GS ≥ 3.1 and only 11 (12%) patients presented with BP, all of them with a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 1. When defining active disease as a GS ≥ 2B.1, the proportion (%) of patients with normal/quiescent/active histological disease was 43/41/16 vs. 36/18/46 for Mayo endoscopic sub-scores 0 and 1, respectively (p = 0.004, Figure 1). Similarly, when defining active histological disease as a GS ≥ 3.1, the proportion (%) of patients with normal/quiescent/active histological disease was 43/44/13 vs. 36/21/42 for Mayo endoscopic sub-scores 0 and 1, respectively (p = 0.003).

Figure 1.

Relationship between endoscopic and histologic activity (active disease defined as a Geboes’ score ≥ 3.1).

The relationship between GS and the Mayo endoscopic sub-score was poor (Spearman correlation = 0.27 (p = 0.007)). Relation between GS and C-reactive protein as well as between GS and Mayo endoscopic sub-scores was also poor (0.09 (p = 0.406) and 0.009 (p = 0.931), respectively).

In none of the patients was the medical therapy adapted based on the endoscopic and histological findings.

Risk factors for clinical relapse

A total of 22 (23%) patients relapsed within the 12-month follow-up period. In univariate analysis, a shorter disease duration (median 13.0 (IQR 9.0–21.0) years vs. median 7.5 (IQR 1.8–15.3) years; p = 0.015) and active histological disease (defined either as GS ≥ 3.1 (16% vs. 46% patients; p = 0.004) or GS ≥ 2B.1 (16% vs. 46% patients; p = 0.002) were significantly different between non-relapsers and relapsers.

The area under the curve (AUC) for GS ≥ 2B.1 and GS ≥ 3.1 to predict clinical relapse was 0.643 ((95% confidence interval (CI) 0.508–0.777); p = 0.035) and 0.646 ((95% CI 0.506–0.787); p = 0.038), respectively.

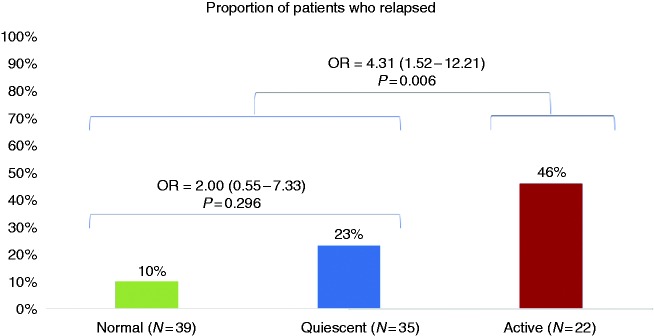

When subdividing histological grades in normal /quiescent/ active disease, the proportions (%) of patients who presented with a clinical relapse within one year were 10/23/46 (p = 0.007) for a GS ≥ 3.1 cutoff and 10/22/44 (p = 0.007) for a GS ≥ 2B.1 cutoff. Results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Risk of relapse according to the different grades of histologic activity (active disease defined as a Geboes’ score ≥ 3.1). OR: odds ratio.

None of the other demographic, clinical, biological or histological features were found to be a risk factor for clinical relapse. Results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk factors for relapse within 12-month follow-up. Univariate analysis.

| N = 96 | No relapse (n = 74) | Relapse (n = 22) | p c,d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 30 (40) | 7 (32) | 0.487 |

| Median (IQR) age (years) | 51.0 (41.0–58.0) | 44.5 (37.5–60.8) | 0.210 |

| Median (IQR) disease duration (years) | 13.0 (9.0–21.0) | 7.5 (1.8–15.3) | 0.015 |

| Median (IQR) time from last relapse (months) | 25.0 (7.3–67) | 22.0 (12.0–33.0) | 0.964 |

| Montreal classificationa (%): E1/E2/E3 | 10/34/29 (14/47/39) | 4/11/7 (18/50/32) | 0.763 |

| Active smoking (%) | 7 (9) | 2 (5) | 0.827 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis (%) | 8 (11) | 0 | 0.194 |

| Median (IQR) C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 6 (9) | 15 (25) | 0.382 |

| Median (IQR) hemoglobin (g/dl) | 14.2 (13.1–15.3) | 13.6 (12.7–15.3) | 0.410 |

| Median (IQR) WBC (109/l) | 6.1 (4.9–7.9) | 6.1 (5.4–8.5) | 0.455 |

| Median (IQR) platelets (109/l) | 255.0 (202.0–295.0) | 246.5 (210.3–284.0) | 1 |

| Geboes’ score ≥ 2B.1(%) | 14 (19) | 11 (50) | 0.004 |

| Geboes’ score ≥ 3.1(%) | 12 (16) | 10 (46) | 0.004 |

| Basal plasmacytosis (%) | 6 (8%) | 4 (18%) | 0.236 |

| 5-ASA/immunosuppressantsb/anti-TNF | 50 (67) | 15(68) | 0.894 |

| Immunosuppressantsb | 16 (21) | 4 (18) | 1 |

| Anti-TNF | 24 (32) | 8 (36) | 0.702 |

UC extension according to Montréal classification (proctitis (E1), left-sided colitis (E2) extensive colitis (E3)). bImmunosuppressants, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, tacrolimus. cp: calculated by χ2 test for qualitative variables. dp: calculated by Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables.

IRQ: interquartile range; 5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylates; Anti-TNF: anti-tumor necrosis factor; WBC: white blood cells.

In multivariate analysis, only active disease on histology defined as GS ≥ 3.1 remained as an independent risk factor for clinical relapse (odds ratio (OR) 4.31 (95% CI 1.52–12.21); p = 0.006). Similar results were observed when active disease was defined as a GS ≥ 2B.1 (OR 4.29 (95% CI 1.55–11.87); p = 0.005).

None of the patients was hospitalized and/or underwent colectomy within the 12-month period follow-up.

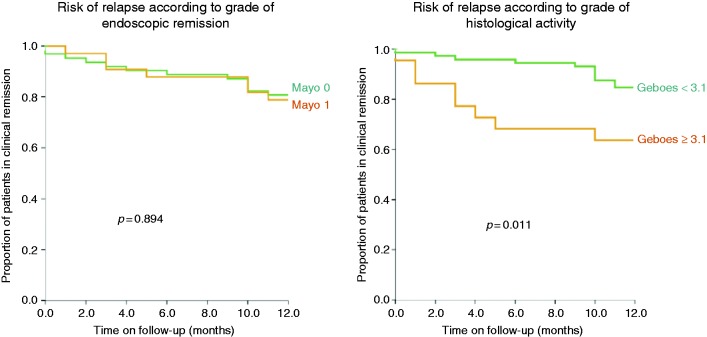

Risk of clinical relapse according to the degree of endoscopic and histological remission

Of note, clinical relapse rate was similar regardless of the degree of endoscopic remission, since 21% and 27% of patients with a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0 and 1 respectively relapsed within one year (p = 0.438). Comparing the risk of clinical relapse through a Kaplan-Meier curve, we observed that a GS ≥ 3.1 but not the Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 1 (vs. Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0) was a risk of clinical relapse during the 12-month follow-up period (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk of clinical relapse during the 12-month follow-up period according to endoscopic and histological activity.

Finally, when selecting only patients with a Mayo endoscopic sub-score grade of 0 (n = 63), histological activity was not found to be a risk factor of clinical relapse, although the low sample size might play a role in this context. The relapse rates were 18% and 38% for patients with a GS < 3.1 and GS ≥ 3.1, respectively (p = 0.345). Similar results were found for the GS ≥ 2B.1 cutoff (data not shown).

Discussion

This prospective study shows the impact of active histological disease on the risk of clinical relapse in patients with UC who are in both clinical and endoscopic remission.

During the last decades, treatment goals in patients with UC have shifted from clinical remission only to clinical remission combined with MH. Indeed, MH was shown to be associated with better mid-term outcomes in patients with UC.1,2 However, since active microscopic disease in the presence of MH has shown to have a potential prognostic value, histological healing has been more recently proposed as a new therapeutic goal in UC.19 However, before histological healing can be proposed as an additional target, more evidence about the prognostic value is needed as well as standardization of the definition regarding histological activity.

Already in 1991 Riley et al. showed that an acute inflammatory cell infiltrate was a risk factor for clinical relapse in a cohort of 82 UC patients in clinical and endoscopic remission.4 Later on, other authors also demonstrated that histological activity has a prognostic value in this group of patients.6,7,20,21 However, the definitions for active microscopic disease varied significantly among these studies. The presence of intraepithelial neutrophils and BP have been the most commonly used. In this line, histological assessment in UC needs to be standardized since at least 20 different histological scores18,22–24 have been developed. Moreover, a clear definition of histological remission has not been established yet. Among all scores, the GS has probably been the most used and detailed, but its complexity (seven different grades divided into four or five subcategories each) could limit its use in clinical practice. Moreover, this score does not include the variable of BP, which has been independently related to a higher risk of clinical relapse in patients with clinical and endoscopic remission.5,6 In order to overcome these limitations, we recently developed a simplified score of the GS that includes BP as one of the histological variables and reduced the number of categories.24

In order to confirm our previous results from a retrospective cohort,6 we assessed histological activity according to GS but also the variable BP. The simplified GS was not used since this study was initiated before its development.

Histological activity has demonstrated to be a predictor of clinical relapse but also of other outcomes such as the need for steroids, hospitalization and response to treatment.25,26

In our cohort, the presence of neutrophils either in the lamina propria (GS = 2B.1) or in the epithelium (GS = 3.1) was the only independent risk factor to predict clinical relapse in UC patients in clinical and endoscopic remission. Of note, histological activity was a stronger predictor of clinical relapse than endoscopic activity defined by a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 1 in this cohort of UC patients in clinical remission with a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0 or 1. The cutoff for active histological disease in UC patients is a matter of debate.

Despite the fact that in other studies the GS ≥ 3.1 cutoff has been proposed to be the most accurate cutoff to predict clinical relapse,6,21 there are no data about the potential accuracy of a GS cutoff of 2B.1 in this context. The presence of extravascular neutrophils in the mucosa (regardless of their location) might be a risk factor for clinical relapse. Only in some specific situations (such as a strenuous bowel preparation or mucosal irritation due to a difficult endoscopic procedure), might the presence of isolated neutrophils in the mucosa not imply active disease. However, in these situations the location of the biopsies will clarify this in most cases. In this context, we performed the analysis with both cutoffs (GS ≥ 3.1 and GS ≥ 2B.1) obtaining similar results to predict risk of relapse in UC patients in clinical and endoscopic remission.

Other studies also found that BP together with neutrophils was a risk factor for clinical relapse.5,6 In our cohort, the global proportion of patients with BP was very low (12%), which might underestimate the capacity of BP to predict clinical relapse. One of the possible reasons why our cohort presented with such a low rate of BP might be the fact that patients were in a long-lasting remission period prior to their inclusion in the study.

Apart from histological activity, almost no other risk factors for clinical relapse in UC patients in remission have been reported in the literature. Bitton et al. demonstrated that the presence of multiple previous relapses and a younger age were related to a higher risk for clinical relapse.5 Fecal calprotectin is increasingly being reported in recent studies as one of the most accurate markers of histological activity in UC patients as well as a risk factor for clinical relapse.27–29 In our cohort, only a shorter disease duration (median 7.5 years vs. 13.0 years) was a predictor for clinical relapse in the univariate analysis, besides histological activity. However, in the multivariate analysis only active histological activity remained significant. Neither the grade of endoscopic remission (Mayo endoscopic sub-score grade 0 or 1) nor any of the other epidemiological and clinical variables were found to be risk factors for clinical relapse in our study.

One of the limitations of our study is that fecal calprotectin was not systematically measured and was therefore not included in the analysis. Another limitation is that, because this was a multicenter study, the location of biopsies was not standardized but was performed according to endoscopist criteria in the context of dysplasia surveillance colonoscopy. However, this also shows more closely the real-life experience in many centers.

In conclusion, our study shows that histologically active disease defined by the presence of neutrophils either in the lamina propria or also in the epithelium has a prognostic value in UC patients in clinical and endoscopic remission. These patients are therefore at increased risk for flares and should probably be followed closely. Further prospective, randomized, controlled studies should now demonstrate whether treatment optimization is indicated in these patients to prevent flares. A standardization of concepts regarding histological activity in UC is also needed.

Declaration of conflicting interests

TL has nothing to declare. TB receives financial support for research from Janssen and Abbvie; lecture fees from Abbvie, Takeda, Pendopharm, Ferring and Shire; and consultancy from Abbvie, Takeda and Pfizer. ARC has nothing to declare. GDH receives financial support for research from Genentech, Galapagos and Centocor. RB receives financial support for research from Pentax, Fujifilm, Cook and Ipsen; lecture fees from Ferring, Norgine, Pentax, Fujifilm, Olympus and Medtronic; and consultancy from Norgine, Pentax, Fujifilm and Boston; JG has nothing to declare. GVA receives financial support for research from Abbott and Ferring; lecture fees from Janssen, MSD and Abbvie; and consultancy fees from PDL BioPharma, UCB, Sanofi-Aventis, Abbvie, Ferring, Novartis, Biogen, Janssen, NovoNordisk, Zealand, Takeda, Shire, Novartis and Bristol. SV receives grant support from MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer and Takeda; lecture fees from Abbvie, MSD, Ferring, Takeda and Hospira; and consultancy fees from Abbvie, Takeda, Pfizer, Ferring, Shire, MSD, Hospira, Mundipharma, Celgene, Galapagos and Genentech. MF receives financial support for research from Takeda; lecture fees from Abbvie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Tillotts and Zeria; and consultancy from Abbvie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ferring, Janssen, MSD and Pfizer.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University Hospitals of Leuven (B322201213950/ S53684) on March 29, 2012, and the Ethical Committee of Bellvitge University Hospital (PR 181/10) on December 23, 2010. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Raf Bisschops, Gert Van Assche, Séverine Vermeire, and Marc Ferrante are senior clinical investigators of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO).

Informed consent

All patients gave written informed consent.

References

- 1.Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Reinisch W, et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2011; 141: 1194–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meucci G, Fasoli R, Saibeni S, et al. Prognostic significance of endoscopic remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis treated with oral and topical mesalazine: A prospective, multicenter study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18: 1006–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, et al. Microscopic activity in ulcerative colitis: What does it mean? Gut 1991; 32: 174–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitton A, Peppercorn MA, Antonioli DA, et al. Clinical, biological, and histologic parameters as predictors of relapse in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessissow T, Lemmens B, Ferrante M, et al. Prognostic value of serologic and histologic markers on clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with mucosal healing. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1684–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azad S, Sood N, Sood A. Biological and histological parameters as predictors of relapse in ulcerative colitis: A prospective study. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2011; 17: 194–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, et al. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: A cohort study. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 1099–1105. quiz 1340–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin DT, Huo D, Kinnucan JA, et al. Inflammation is an independent risk factor for colonic neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis: A case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 1601–1608.e1-e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regueiro M, Rodemann J, Kip KE, et al. Physician assessment of ulcerative colitis activity correlates poorly with endoscopic disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17: 1008–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombel JF, Keir ME, Scherl A, et al. Discrepancies between patient-reported outcomes, and endoscopic and histological appearance in UC. Gut 2017; 66: 2063–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, et al. Why do patients with ulcerative colitis relapse? Gut 1990; 31: 179–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patil DT, Moss AC, Odze RD. Role of histologic inflammation in the natural history of ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2016; 26: 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geboes K, Riddell R, Ost A, et al. A reproducible grading scale for histological assessment of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gut 2000; 47: 404–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magro F, Langner C, Driessen A, et al. European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2013; 7: 827–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryant RV, Winer S, Travis SP, et al. Systematic review: Histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is ‘complete’ remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8: 1582–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: Current management. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6: 991–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchal Bressenot A, Riddell RH, Boulagnon-Rombi C, et al. Review article: The histological assessment of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 957–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Bressenot A, Kampman W. Histologic remission: The ultimate therapeutic goal in ulcerative colitis? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 929–934.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg L, Nanda KS, Zenlea T, et al. Histologic markers of inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 991–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zenlea T, Yee EU, Rosenberg L, et al. Histology grade is independently associated with relapse risk in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission: A prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111: 685–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchal-Bressenot A, Salleron J, Boulagnon-Rombi C, et al. Development and validation of the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut 2017; 66: 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosli MH, Feagan BG, Zou G, et al. Development and validation of a histological index for UC. Gut 2017; 66: 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jauregui-Amezaga A, Geerits A, Das Y, et al. A simplified Geboes score for ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2017; 11: 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: Histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut 2016; 65: 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zezos P, Patsiaoura K, Nakos A, et al. Severe eosinophilic infiltration in colonic biopsies predicts patients with ulcerative colitis not responding to medical therapy. Colorectal Dis 2014; 16: O420–O430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guardiola J, Lobatón T, Rodríguez-Alonso L, et al. Fecal level of calprotectin identifies histologic inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical and endoscopic remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 1865–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jauregui-Amezaga A, López-Cerón M, Aceituno M, et al. Accuracy of advanced endoscopy and fecal calprotectin for prediction of relapse in ulcerative colitis: A prospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20: 1187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zittan E, Kelly OB, Kirsch R, et al. Low fecal calprotectin correlates with histological remission and mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis and colonic Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016; 22: 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]