Abstract

Following deceased organ donation and transplantation, the narratives of families of donors and organ recipients become connected. This is acknowledged when parties receive anonymous information from donation agencies and transplant centres, when they exchange correspondence or when they meet in person. This article reviews literature describing the experience from the points of view of donor families, recipients, and other stakeholders to explore the dynamic system that evolves around this relationship. Findings highlight a link between identity development and ongoing adjustment and will assist those supporting donor families and recipients to make decisions that fit meaningfully.

Keywords: bereavement, donor families, healthcare systems, organ donation, organ transplantation, posttraumatic growth, recipients, relationship, systemic

Introduction

This article explores the relationship between transplant recipients and families of post-mortem organ donors. While organ transplantation is often described as a medical breakthrough, its ultimate success depends on the recipient’s psychological coping and ability to comply with their treatment regimen (Rivard et al., 2005). This is in turn influenced by the extent to which a positive self-image can be maintained while resolving the personal and emotional dilemma of living because of someone’s death (Rivard et al., 2005).

This observation is supported by Kaba et al. (2005) who found that most recipients experienced gratitude and appreciation to the donor and their family and regret that someone had to die to enable their transplant to take place. Some recipients report having concerns about their self-concept after receiving an organ from someone else (Bunzel et al., 1992; Kaba et al., 2005) and may feel guilty or unworthy (Rivard et al., 2005).

Bereavement experiences of families of deceased organ donors include awareness that parts of their relative’s body sustain life for transplant recipients (Holtkamp, 2002), pain following sudden death, hope of continued life and feelings of connection with organ recipients (Maloney, 1998; Sque et al., 2006, 2008)

It is unclear how families should respond to this sense of connection (Schweda and Wohlke, 2013). For example, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2010) declares that organisations must ensure ‘… that the personal anonymity and privacy of donors and recipients are always protected’ (p. 9). Strict adherence to such guidelines would protect confidentiality but diminish the autonomy of those involved (Schweda and Wohlke, 2013).

Annema et al. (2013) report that in the Netherlands, anonymity enables parties to avoid adverse consequences such as feelings of obligation, emotional issues, or disappointment when expectations are not met.

Congruent with WHO (2010), studies have found that physicians (Ono et al., 2008), and donation/transplantation professionals (Politoski et al., 1996) prefer anonymity in the relationship between donor families and recipients. However, conveying their gratitude while writing a letter wherein they cannot refer to themselves, their family or their work in an identifiable way (Poole et al., 2011b; Shaw, 2012) can be stressful for recipients.

Studies have found that up to 91 per cent of donor families desire some information about recipients (Bartucci and Seller, 1986, 1988; Mehakovic and Bell, 2015; Northam, 2015), with up to 60 per cent expressing interest in meeting recipients (Ashkenazi, 2013).

In response, some donation and transplantation organisations provide donor families with non-identifiable demographic data, brief descriptions of transplant outcomes and information about the recipient/s’ progress. Recipients may also receive non-identifiable information about the donor, and anonymous written correspondence between parties is often facilitated (Bartucci and Seller, 1986, 1988; Mehakovic and Bell, 2015) with support provided where required (Selves and Burroughs, 2011). Researchers have suggested that more support should be proactively offered to encourage the exchange of anonymous correspondence, with parties being made aware of the benefits of communication (MacKay, 2014; Tolley, 2018a).

While most donor families and recipients are satisfied with anonymous correspondence, finding it comforting and reassuring (Barnwell, 2005; Kaba et al., 2005; Maloney, 1998), for others this is insufficient. Some recipients want to express their gratitude in person, and some donor families want to meet the recipients affected by their donation decision (Albert, 1998; Annema et al., 2013).

Corr et al. (1994) argued that an evidence-based theoretical foundation should guide practices related to contact between donor families and recipients. More research is required to determine the value or risk of various forms of contact and processes of providing options to donor families and recipients (Post, 2015). Open discussion of matters could contribute to shared understanding and policies that are acceptable to all (Corr et al., 1994; Poole et al., 2011a).

Method

The current review explores what is known about this topic and considers perspectives and experiences of donor families, recipients, healthcare professionals and organisations involved while seeking to understand the factors contributing to the desire for contact. It is hoped that a deeper understanding of the context will lead to the development of responses that fit well and are meaningful.

Aim

To explore the desire for contact between donor families and recipients and consider whether some form of contact either assists or hinders the processes of adapting and psychological coping that each must undertake. The potential roles of organ donation and transplantation agencies and the suitability of metaphors used when referring to the relationship between the recipient and the donor’s family are also considered.

Data collection

SAGE, Google Scholar, PsycARTICLES, Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine), Embase, Ovid MEDLINE(R), PsycINFO and PubMed databases were searched on 15 January 2018 using the keywords: (organ donation OR organ donor OR donate OR organs OR organ) AND (family OR recipient OR recipients OR transplant) AND (correspondence OR contact OR meet OR communicate OR relationship).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

No limits were used for time or type of source. English sources commenting on the experience of connection between donor families and deceased donors, transplant recipients and deceased donors, and recipients and donor families were included. Sources that described living donation or tissue-only donation were excluded.

Additional sources

A further 55 sources known to the authors were added to those identified via the above-mentioned search.

Data analysis

Data were analysed qualitatively, first by identifying logical categories which represent different views and experiences of the relationship between donor families and recipients. Key sections were then compared to facilitate a double description (Bateson, [1972] 1987, 1979; Dalton, 2014; Hui et al., 2008; Shotter, 2009), where abductive and inductive reasoning could be used to develop systemic hypotheses. Just as binocular vision contributes to depth perception, the various views collectively contributed to depth in understanding.

Findings

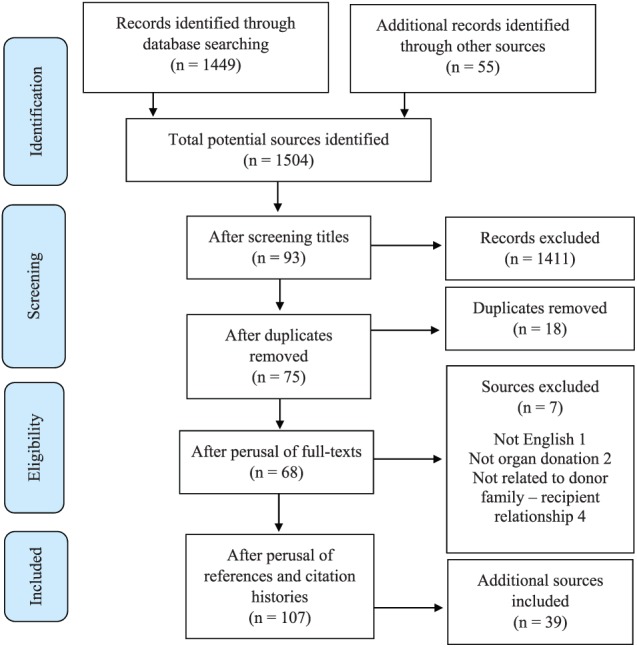

As described in Figure 1, the search strategy identified 1449 potentially relevant sources and these were added to the previously identified 55 sources. After the screening of titles, 93 sources remained, of which 18 were duplicates, and these were removed. Full-text copies of the remaining sources were obtained and after perusal of these, a further seven titles were removed as they did not meet inclusion criteria. The references sections and citation histories of the remaining 68 sources were perused contributing to the inclusion of an additional 38 relevant sources. Full-text copies of these were obtained, and data were extracted from the resultant set of 106 sources. Just before publication of this article, another relevant article, Azuri and Tarabeih (2018) was published and was incorporated into the review, giving a total of 107 sources.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing selection of sources.

Sources selected included reports on original research studies, theoretical articles and commentaries, chapters from books, posters and abstracts from conferences and grey literature including guidelines used by donation and transplantation agencies and documents and reports prepared for government departments. Some of these focus on the donor family perspective, while others focus on the recipient perspective. Some deal specifically with communication and contact between the parties.

Evaluation of sources

Given the various types of sources, direct comparison or evaluation using a single tool seemed inappropriate. Instead, to produce an inclusive and trustworthy consolidation, the authors of this study have incorporated various (sometimes conflicting) findings of the selected sources, contributing to descriptions that are representative of the views expressed. This review does not aim to find the ‘truth’ or establish a ‘correct’ way to conceptualise or respond to requests for contact between donor families and recipients but rather to develop working hypotheses that fit the data.

Data extraction

Data extracted from the selected sources were arranged into five sections. These include the perspective of the bereaved donor family, the perspective of the transplant recipient, metaphors and ways of viewing organ donation and transplantation, contact between donor families and recipients, and views of healthcare professionals, donation agencies and transplant centres. These sections are described in detail later to provide readers with the opportunity to judge the suitability of the final hypotheses themselves.

Data analysis

Using Bateson’s ([1972] 1987, 1979) method of double description, similarities, differences and relationships between the sections were explored abductively and inductively (Dalton, 2014; Hui et al., 2008; Shotter, 2009). This method contributed to the emergence of an eco-systemic understanding of the context which is described in the ‘Discussion’ section later.

Background

Before the identified sections are described, origins of the current context will be discussed. In the 1970s, following the first heart transplant, formalisation of the diagnosis of brain death, and development of improved immunosuppressant medication, members of the public were made aware of the need for post-mortem organ donation (Fox and Swazey, 1992). The value of transplantation was demonstrated by allowing newspaper articles to show pictures and share the stories of deceased organ donors and transplant recipients (Christopherson and Lunde, 1971).

Fox and Swazey (1992) describe the history of organ donation and transplantation and report that medical teams in the late 1960s and early 1970s believed that recipients and donor families had the right to know each other’s identity, feeling that this would enhance meaning and provide a sense of completeness. Identifying information was exchanged, and parties were able to have direct contact.

Although news stories may have contributed to public awareness and acceptance of organ donation and transplantation, Christopherson and Lunde (1971) report that the donor families and recipients involved were dissatisfied with the lack of control they had when their stories were made public. Following this observation, meetings were held between transplant centres and newspaper editors, and restrictions were placed on the information that could be published (Christopherson and Lunde, 1971).

At the same time, medical teams noticed the extent to which some donor families and recipients became involved in each other’s lives, the way that recipients personified the organ as they found out more about the donor and the way that the donor family at times experienced a second bereavement when contact with the recipient was lost or the recipient died (La Spina et al., 1993). As a result, transplant centres decided that information should be restricted, leading to policies that kept the exchange anonymous.

In this way, inappropriate publicity and lack of confidentiality contributed to the development of legislation designed to protect donor families and recipients from the public and each other (Post, 2015). These laws, which are still in use in many countries today, require anonymity and restrict contact between donor families and recipients to de-identified correspondence forwarded by donation and transplantation agencies (Mehakovic and Bell, 2015; Post, 2015).

However, while practices ensuring anonymity changed the way that information was handled, donor families and recipients were still not given control over their own information. In many countries those who wish to make direct contact or provide their details to the other party are unable to do so, contributing to frustration, powerlessness and the inability of parties to decide for themselves about contact. Donor families have highlighted the contradiction of being viewed as capable of providing consent to donation but unable to decide about contact with recipients (Albert, 1999).

This focus on vulnerability is highlighted by reports that donor families and recipients have been advised by donation agencies and transplant centres, respectively, to focus on managing their own stress and not on the other party (Albert, 1999; Corr et al., 1994).

International research shows that many donor families and recipients are satisfied with anonymity, while others desire direct contact (Annema et al., 2013). In Israel and the United States of America, direct contact is facilitated when both parties have expressed a desire to meet (Albert, 1998, 1999; Azuri et al., 2013; Vajentic, 1997).

Lewino et al. (1996) argued that decisions about contact between donor families and recipients should be informed by research rather than speculation. Clayville (1999) agreed, commenting that decisions about communication were often made by representatives from organisations and based on personal beliefs or agency guidelines. To facilitate a holistic picture of this context informed by previous research, extracted data are described next with reference to the five sections mentioned earlier.

Section 1: the perspective of the bereaved donor family

When deciding about donation, families consider the donation preferences of the deceased, the attitudes of family members towards donation, their relative’s personality traits, family members’ pre-death relationship with the deceased, and the implications for their ongoing psychological relationship (Ralph et al., 2014; Sharp and Randhawa, 2014) in addition to the implications for those on transplant waiting lists.

Sque et al. (2006, 2008) highlight the family’s need to let go of their instinct to protect their relative’s body and attach their sense of connection to a psychological image of the deceased as a person separate from their body. After accepting their relative’s death, the relocation of their attachment in this way makes organ donation possible.

Researchers have found that consenting families want to honour the preferences of the deceased (Dodd-McCue et al., 2006), help others (Bartucci, 1987) and demonstrate altruism (Neate et al., 2015). Knowing that their loved one contributed to the lives of others can assist families with their trauma and loss by providing a positive outcome and a sense of peace (Manuel et al., 2010) while contributing to their relative’s biography and the family’s narrative (Sque and Long-Sutehall, 2011). To attend to these tasks, families require evidence of the transplant and the benefits that it has provided (Corr et al., 1994; Larson et al., 2017; Northam, 2015; Steed and Wager, 1998).

Jensen (2010) notes that one of the ambiguities of the donor family’s grief is that recipients remind the family of the death and the ‘separating’ of parts of the body and simultaneously represent a sense that the donor is ‘living on’. Subsequently, some families experience a connection to recipients who sustain part of their relative (Fox and Swazey, 1992; Holtkamp, 2002).

Holtkamp (2002) reports that with the absence of information about recipients, families may imagine recipients to be of a similar age and gender as that of the donor, with parents at times saying that they consented to donation so that other parents would not have to lose a child. In contrast, while most donor hearts at the time came from males aged 18–27 years, most heart transplant recipients were males in their 50s.

Ashkenazi (2013) found that 24 per cent of donor parents were satisfied to know only the outcome of transplantation and 12 per cent expressed no interest in meeting with recipients, while 60 per cent were interested in direct contact.

Researchers exploring this context argue that donor families need to be recognised, appreciated and provided with information, acknowledgement and reassurance (Bartucci and Seller, 1988; Pittman, 1985).

Such needs appear to motivate their interest in the recipient, with the hope that their decision will be recognised, valued and not forgotten (Galasiński and Sque, 2016; Gideon and Taylor, 1981; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Northam, 2015; Painter et al., 1995; Pittman, 1985; Sque and Payne, 1996).

Most donor family members think about the recipients at some point (Fulton et al., 1977) and appreciate receiving de-identified information or a letter which confirms that transplantation has taken place (Albert, 1998; Azuri and Tabak, 2012; Bartucci and Seller, 1986, 1988; López Martínez et al., 2008; Mehakovic and Bell, 2015; Ono et al., 2008; Pelletier, 1993; Sanner, 2001).

In these ways, the family’s primary struggle of coming to terms with a sudden death can become linked to their donation decision and a sense of connection with transplant recipients. This link may not be equally strong for all families, and further research is required to improve the understanding of differences between families (Cerney, 1993).

Researchers have proposed that the bereavement experience of donor families can be understood as a response to traumatic bereavement where meaning-making, attachment theory, continuing bonds, and narrative provide insight into their needs and actions.

Holtkamp (2002) noted that those bereaved following a traumatic incident often describe an intense need to understand and make sense of the events surrounding the death (Rando, 1993). In the organ donation context, families need to make sense of an unusual death, confusing in-hospital experiences, the family’s donation decision, and post-donation outcomes.

The bereaved experience a yearning and searching for the lost person (Holtkamp, 2002) even after accepting the death. This is in response to separation from someone which whom strong attachment bonds existed and is part of the process of adapting rather than being pathological (Rando, 1993). In the present context, meaning-making and yearning may coincide with a strong need for information about the recipient/s (Holtkamp, 2002).

After a death, a psychological bond (Silverman et al., 1996) can facilitate the bereaved’s ongoing relationship with the deceased which, after consenting to donation, may become entwined with a sense of connection with recipients (Schweda and Wohlke, 2013). While for some families, knowing transplant outcomes is sufficient evidence of this connection, others would like to meet with recipients to witness the outcomes in a tangible form (Ashkenazi, 2013).

Sque and Long-Sutehall (2011) described the family’s bereavement experience from the perspective of biography and narrative, noting that the biographies of the donor and recipient are separate, but overlap. Acknowledgement of this overlap can contribute to honouring of the donor, making sense of traumatic death, and finding solace in a difficult situation (Corr et al., 2011).

Many donor families want to share information about their relative with recipients (Albert, 1999) and obtain information about recipients. This information contributes to the biography of the deceased and is part of the family’s ongoing narrative. Without information about (or in some cases, contact with) recipients, families may feel that the narrative is incomplete and they may wonder whether the organ donation (attributed to the donor) was valued (Northam, 2015; Sque and Long-Sutehall, 2011).

Nevertheless, there is risk involved. La Spina et al. (1993) found that in addition to helping others, some families described keeping part of the deceased alive by identifying them with the recipients. Concerned that this may complicate bereavement, La Spina et al. (1993) suggested that identification with recipients should be discouraged, and the finality of death should be emphasised. Pittman (1985) was also concerned that transferring attachment from the donor to the recipient with a sense of continuing life may complicate grieving.

Those caring for families could assist members to balance factors such as acknowledgement of death, a focus on reconstructing their lives, establishing a psychological bond with the deceased (Stroebe and Schut, 1999; Worden, 2009), and a sense of connection with recipients without depending on recipients to maintain a connection with the donor.

Section 2: the perspective of the transplant recipient

Patients with organ failure experience anxiety and stress (Jones et al., 1986), while adjusting to emotional, cognitive, and social changes. They often experience loss of autonomy, social roles, and activities while facing limited life expectancy (Schulz and Kroencke, 2015).

The news of their need for a transplant contributes to further changes (Forsberg et al., 2016). When deciding to begin work up towards being placed on a transplant waiting list, most potential recipients consider the risks and benefits of transplantation in terms of what has been explained to them, and few thoroughly consider the implications for donors and their families at that stage (Kandel and Merrick, 2007).

During the months following the transplant, recipients adapt to the restrictions required by their treatment regimen and gradually reconstruct their lives as people living post-transplant (Forsberg et al., 2016). Despite risks and restrictions related to their treatment, recipients experience better health, improved life expectancy and are less anxious compared to pre-transplant (Jones et al., 1986).

It has been found that during this time, many recipients think about the organ donor (Annema et al., 2013; Goetzmann et al., 2009), and report that they would appreciate some information about their donor’s age, sex, and general health. On the other hand, Goetzmann et al. (2009) found that 2.7 per cent of recipients felt significant guilt towards the donor and had difficulty integrating the organ, which predicted low disclosure to others about having received a transplant and had implications for social support and non-adherence.

Perhaps to avoid this risk, explanations that are given to recipients by their transplant team often suggest that transplantation should be seen as an ‘exchange of spare parts’ (Mauthner et al., 2015), encouraging the recipient to disassociate from their donor (Sanner, 2001; Sharp, 1995). However, this view does not incorporate the possibility of recipients contacting the family of the donor which requires acceptance of the donor’s death and their family’s grief (Poole et al., 2011b; Sanner, 2003).

Similarly, Siminoff and Chillag (1999) comment on how awareness campaigns often employ the ‘altruistic gift’ metaphor which does not adequately address the pain of the donor family. Simultaneously encountering the replaceable parts metaphor, the gift metaphor, and the possibility of contact with the donor’s family complicates the donor-recipient relationship and may contribute to distress (Mauthner et al., 2015) rather than resolving it.

In addition, Sanner (2001) found that many recipients used another model analogous to mixtures where the resultant body would be expected to contain qualities of the transplanted organ. Likewise, Kaba et al. (2005) found that up to a third of recipients wonder if personality or behavioural changes experienced post-transplant are related to the donor.

Sanner (2001) stresses that recipients experience changes in response to being chronically ill and then receiving a transplant, hypothesising that some recipients project their own post-transplant characteristics onto their representation of the donor. Sanner (2001) advises that healthcare professionals should remain open to hearing their patients’ perceptions.

Other researchers argue that heart transplant recipients at times experience behavioural and personality changes (preceding contact with the donor’s family) that are too closely related to traits of their donors to be explained by chance (Pearsall et al., 2002; Wright, 2008). These researchers suggest that all living cells possess memory and ‘decider’ systems that may be incorporated through transplantation.

Whichever explanation is taken as valid, for some recipients their experience contributes to identity disruption which may be demonstrated by over-determined insistence that nothing has changed (Bunzel et al., 1992), a heightened sense of anxiety associated with the transplanted organ as a foreign part, or an excessive feeling of kinship with the donor’s family (Goetzmann et al., 2009; Mauthner et al., 2015).

Goetzmann et al. (2007) found that lung recipients who reported either an emotional distance from the lung (seeing it as a foreign part) or felt as if they were influenced by the donor experienced more distress (Kaba et al., 2005) and were less compliant with their medical treatment post-transplant. They had difficulty balancing the integration of the organ into their sense of self and maintaining a distance between their identity and that of the donor.

Despite their struggles recipients can be assisted to incorporate the graft over time, easing stress and improving recovery and treatment adherence (Latos et al., 2016; Mauthner et al., 2015). Compliant recipients in these studies thought about the donor and imagined personality traits of the donor without experiencing anxiety.

These experiences may represent different stages of adjustment post-transplant in that researchers studying lung (Goetzmann et al., 2009), heart (Kaba et al., 2005), and kidney (Latos et al., 2016) recipients found that the transplanted organ is initially seen as a foreign part and then through a process of integration (which may include psychological conflict and physical complications) the organ is gradually seen as a part of the recipient’s perceived sense of self.

Sanner (2003) observed that many recipients appeared to split their perceptions of the organ itself as a functional part and the donor-as-a-person, allowing them to develop a relationship with each separately. Sanner (2003) noticed that recipients often experienced a challenge to their sense of identity which was described in terms of influence-identification.

During identification, thoughts of the ‘donor as a fellow being like me’ seemed to eliminate the need for fear of being influenced, creating a sense of equality (Sanner, 2003). This may, in turn, contribute to psychological well-being, an improved quality of life, and compliance with medical treatment (Denny and Kienhuis, 2011). However, developing an overly close psychological relationship with the donor which is characterised by being mentally preoccupied and feeling that character traits of the donor have been ‘inherited’ appears to contribute to increased psychological distress for 10 to 20 per cent of recipients (Kaba et al., 2005), with a possible influence on treatment compliance (Goetzmann et al., 2009).

Sanner (2003) developed a model describing post-transplant coping. The first two elements of the model were organised in terms of the continua of joy–sorrow and gratitude–indebtedness. The third and fourth elements were named guilt and inequity, respectively. However, consideration of Sanner’s (2003) descriptions of these latter categories suggests that they could have been organised around the continua of guilt–innocence and inequity–equilibrium, respectively.

Sanner’s (2003) continua are described in more detail in Table 1. The categories discussed are not static, with individual recipients moving between them at a given time or over time (Sanner, 2003).

Table 1.

Recipient perceptions of the organ, the donor, and the donor’s family (Sanner, 2003).

| Dimension | Description of the extremes of the continua | |

|---|---|---|

| Joy–sorrow | Joy: Immediately after transplant, recipients typically experienced euphoria and relief. | Sorrow: Acknowledging that a premature death has left another family grieving contributed to sorrow. |

| Gratitude–indebtedness | Gratitude was experienced towards the donor and their family. | Indebtedness: Recipients often felt the need to somehow ‘repay’ the ‘gift’. |

| Guilt–innocence | Guilt: Recipients found it hard to reconcile their hope for an organ being linked to someone else dying. | Innocence: Randomness involved in donation–transplantation implied that they are not responsible for the death. |

| Inequity–equilibrium | Inequity: Recipients reported that they saw it as unfair that someone had to die for another to live. | Equilibrium: Some recipients signed a donor card or behaved in a generous and helpful way themselves. |

| Influence–identification | Influence: Some denied changes, while others wondered whether the donor’s organ influenced them. | Identification: Recipients accepted changes in their identity post-transplant without feeling threatened. |

Sanner (2003) noted that while recipients had discussed a range of feelings, perceptions and adaptive strategies during the research project, they had reported that they did not generally discuss such matters with others. This suggests that the team treating the recipient should not simply assume that any difficulties would be raised, but they should initiate and explore matters with the recipient in a safe context where processes such as those identified are seen as part of normal adaptation following transplant (Mauthner et al., 2015; Pisanti et al., 2017; Sanner, 2003; Sharp, 1995).

Dobbels et al. (2009) found that those recipients who would consider contact with donor families felt a need to know more about the donor, including receiving a picture and wanting to express their gratitude and let the family know about their post-transplant adjustment. These recipients felt that the choice to meet or not to meet should be made by the parties concerned rather than by an organisation or law-makers, and some believed that it would assist their own adjustment if they could choose for themselves.

Considering factors such as those described earlier, researchers have hypothesised that in addition to wanting to make anonymous or direct contact to thank the donor family, recipients may hope that this will assist them to resolve the struggles that they experience (Fox and Swazey, 1992; Holtkamp, 2002).

Section 3: metaphors and ways of viewing organ donation and transplantation

Given that organisations promoting organ donation often use slogans such as ‘Gift of Life’, Glazier (2011) explored the appropriateness of ‘Gift Law’ in the organ donation context. According to this perspective, gifts of any type must fulfil three basic elements to be legally recognised: (1) there must be donative intent, (2) the gift must be physically transferred or delivered and (3) the gift must be accepted. Once all three criteria are met, the gift is complete and enforceable under the law (Glazier, 2011).

Glazier (2011) argues that deceased organ donation is anatomical gifting – the uncompensated transfer of organs from the donor to the recipient. Accordingly, once consent exists, and after the donor has died, the gifted organs may be surgically recovered, transferred and accepted for transplantation.

To further explore the appropriateness of metaphors such as gift and terminology such as altruism, Sharp and Randhawa (2014) compared the notion of altruism (a selfless act without expectation of repayment) and gift giving (where there may be obligations to give, receive and reciprocate).

Sharp and Randhawa (2014) highlighted ways in which cultural views of altruism, gift-giving, perceptions of the body and death all influence family motivations at the time of a potential organ donation and concluded that the concept of altruism does not capture all facets of the organ donation experience, while the notion of gift-giving is problematic given that reciprocation (which is vital for social cohesion and stability) is poorly defined in this context.

In contrast to the focus of gifting and altruism, Christopherson and Lunde (1971) noted that consenting families felt it was important that both their pain and how they were pleased to be able to help someone else were acknowledged. Similarly, one of the participants in Bartucci and Seller’s (1986) study referred to the ‘gift of life from sacrifice’ (p. 403), and La Spina et al. (1993) later concluded that families who decide to consent to donation can simultaneously ‘… act out of generosity … and a willingness to sacrifice’. (p. 1700)

Similarly, Holtkamp (1997) noted that families might feel comforted, but also experience pain and argued that the ‘gift’ should not become the focus at the risk of neglecting family grief. Sque et al. (2006, 2008) explored the simultaneous consideration of donation as a gift and a sacrifice, while Sque and Galasiński (2013) described family members’ struggle with the idea of their loved one undergoing donation surgery, which they may associate with sacrificing the wholeness of the body.

Schweda and Wohlke (2013) conducted focus groups in four European countries to explore the perspectives of donor families and recipients. It was found that in contrast with the dominant narrative of organ donation as an altruistic gift, both parties felt that there was more to the experience. For example, donor families often spoke of organ donation as providing a sense that their deceased relative could continue to have influence because a part of them lived on, sustaining life for a transplant recipient.

Recipients discussed the need to accept and incorporate the donated organ and felt that to receive a transplant was a significant responsibility because of the scarcity of organs. They described the need to look after the organ to honour the intentions of the donor and their family (Goetzmann et al., 2008) and reported feeling a blend of gratitude and guilt (Schweda and Wohlke, 2013).

Donor families are more likely to refer to organ donation as an act of the donor (especially when the donor had registered their preferences before their death) and associate the donation with the donor’s personality and what he or she would have wanted (Bartucci and Seller, 1988) while transplant recipients tend to focus on the donor family’s decision to offer donation when speaking or writing about the event (Galasiński and Sque, 2016).

At the same time, family members claim some stake in the process (e.g. ‘We willingly honoured her wish’). This appears to facilitate a sense of the unity between the family and the donor. Ascribing agency to the donor makes sense if the families’ descriptions are taken as advancing the narrative and biography of the deceased (Galasiński and Sque, 2016).

These observations show that even to the extent that altruism and gift-giving are valid metaphors, they do not consider the complex experience of the donor family and recipient (Sharp and Randhawa, 2014) or the relationship formed between them (Schweda and Wohlke, 2013; Shaw, 2010).

Stoler et al. (2016) describe changes in the law in Israel so that priority on transplant waiting lists can be given to patients who are first-degree relatives of organ donors. Incentives such as these challenge the metaphor of the altruistic gift.

Shaw (2010) spoke to intensivists, donation coordinators and transplant coordinators exploring their views. Many of these participants also argued that the gift metaphor does not adequately acknowledge the extent to which the decision to donate is linked to a sense of pain and sacrifice, which are not generally associated with gift-giving.

Some were uncomfortable with the term ‘gift’ because it did not capture the responsibility that may be felt both by donor families (to make the decision that would be correct for them, their relative, and society) and recipients (to care for the organ) and because gift-giving is generally associated with a pleasurable event which is not the case in organ donation. Others defended the use of the term ‘gift’ because it separated organ donation and transplantation from transactions which involved the exchange of money or the expectation of tangible reward.

Shaw (2010) feels that the incongruence between the ‘gift of life’ discourse and the actual experience of organ donation and transplantation is ethically relevant as it can contribute to an escalation of the ambiguity experienced by the family where they are hesitant because they care about their loved one’s body, but their hesitance implies that they do not care for others.

Such ambiguity can contribute to heightened anxiety, ambivalence and a need to escape from the situation. In such a case, emotionally reactive rather than reasoned decisions can be expected. Whichever way such decisions are made, it is possible that families will later feel regret when they can consider matters without the emotional pressure (De Groot et al., 2012).

Shaw (2010) highlights the need to consider how we talk about organ donation and transplantation as we search for a vocabulary that fits. When popular discourse is more congruent with the actual experiences of donor families and recipients, both parties can be expected to more freely discuss their struggles contributing to more effective support from formal and informal sources. For example, it has been suggested that to rebrand organ donation as an ‘act of charitable donation’ may reduce pressure experienced by recipients who feel that they cannot reciprocate or be worthy of the gift of life (Gerrand, 1994; MacKay, 2014).

Section 4: contact between donor families and recipients

Although Christopherson and Lunde (1971) reported that over time families showed less interest in recipients and focused on their own adjustment, Galasiński and Sque (2016) have argued that the family’s decision affects the rest of their lives. For those who choose to donate, there is often a continuing desire to know more about the organ recipients (Lewino et al., 1996), and during the 1990s, there was an increase in requests from donor families for direct contact (Clayville, 1999). Where studies have been conducted, results indicate that a portion of recipients want direct contact, while others prefer anonymity (Annema et al., 2013; Blaes-Eise and Samuel, 2013).

In Annema et al’.s (2013) study, those recipients preferring anonymity saw it as an expression of mutual respect. Others experienced ambiguity in that they wanted to express their gratitude in person but were concerned about the consequences.

Dobbels et al. (2009) explored the attitudes of Belgian liver transplant recipients at a time when politicians were considering relaxing rules concerning contact with donor families. It was found that 70 per cent of liver recipients were satisfied with laws protecting anonymity and were concerned that relaxing laws would contribute to anxiety, feeling obliged to do something in return for the donated organ, and feelings of guilt. On the other hand, 19 per cent of respondents expressed a desire to know more about the donor and said that they would appreciate an opportunity to thank the donor’s family directly.

Sharp (1995) found that many heart, lung and liver recipients participating in the study had been seeking out their donor’s family and hoped to form relationships with them in spite of professionals’ efforts to maintain anonymity. Some had integrated the real or imagined personality of the donor into their post-transplant identity.

For donor families, the main reason given for wanting contact was to see firsthand what the benefit of their donation decision was to the recipient. Some donor families request ongoing information about recipients (Holtkamp and Nuckolls, 1991, 1993) and want to provide recipients with information about the donor as a person (Barnwell, 2005; Martin, 2017; Politoski et al., 1996).

For the recipients, the main reasons given were to be able to learn more about the donor (Dobbels et al., 2009) and thank the donor family in person (Annema et al., 2013; Azuri and Tabak, 2012; Dobbels et al., 2009; Lewino et al., 1996).

Donor families who did not want contact explained that the recipient’s identity was not important to them and they did not want to relive a painful part of their lives. Recipients who did not want contact felt that they were uncomfortable about being alive while the donor was dead, did not want to cause the donor family to be hurt (Dobbels et al., 2009) or were concerned about what level of involvement donor families may expect. Some reported that not making contact protected them from the emotional nature of meetings with the other party and allowed each to get on with their own life struggles (Azuri and Tabak, 2012).

Older recipients felt uneasy about their age, especially when the donor was young (Lewino et al., 1996) and recipients transplanted after alcoholic cirrhosis or those experiencing significant guilt were less likely to want contact (Annema et al., 2013; Sanner, 2001).

Many, including those who did not wish to make contact themselves, felt that anonymity should not be enforced by law as applicable to everyone, believing that individuals should have the autonomy to decide for themselves (Annema et al., 2013; Olson et al., 1992).

Politoski et al. (1996) found that 59 per cent of donor families felt that initial information confirming the success of transplantation was sufficient at that time and when asked about the desire for further information, several felt that letters (51%), a ‘Thank you’ (20%) and a meeting (25%) would be appreciated later. Given the variety of views regarding contact, it was considered vital that policies were based on an understanding of the grief of donor families and the experience of living with a transplant (Clayville, 1999).

Anonymous correspondence

Acknowledging that some form of contact may be valuable to donor families and recipients, agencies internationally have for some time facilitated the exchange of anonymous correspondence between parties.

Bartucci and Seller (1986) found that regardless of how much time had elapsed between organ donation and the receipt of correspondence from a recipient, or what the cause of death had been, the letter was appreciated and contributed to positive feelings. Several families who had received letters said that they were cherished and added meaning to their decision to consent to organ donation. Families expressed gratitude to the recipients for writing letters that assisted them to put their decision into context (Bartucci and Seller, 1988), were comforting and meaningful (Holtkamp, 1997), confirmed the value of their altruism (Youngner et al., 1985) and diverted their feeling from intense grief to something positive (Bartucci and Seller, 1988).

Poole et al. (2011b) explored the attitudes of heart recipients to the writing of a Thank You letter to donor families and found that most showed significant distress regarding issues such as the obligation to write anonymously and the inadequacy of the ‘thank-you’. Recipients expressed difficulty when considering what to include in the letter (not wanting to say anything that upset the donor family), the process of writing the letter, and waiting for a response (those who wrote often hoped for some response and were frustrated when one was not received). Poole et al. (2011b) suggested that support should be available to recipients when writing letters.

Even when they were able to overcome such barriers, recipients faced the contradiction of writing a personal letter without using any personal details. Wanting to express gratitude but being restricted by rules enforcing confidentiality creates a dilemma that recipients struggle to resolve (Poole et al., 2011b).

In this way, mandated anonymity depersonalises a highly personal act and contributes to stress (Gewarges et al., 2015). Consequently, many recipients do not forward a letter or do so months or years following the transplant (Blaes-Eise and Samuel, 2013; Tolley, 2018a).

This is supported by MacKay’s (2014) finding that 42 per cent of donor families had not received a letter. Researchers have found that while both donor families and recipients desired contact, many had not made contact themselves and were hesitant to do so until receiving correspondence from the other (Lewino et al., 1996; Politoski et al., 1996). Azuri and Tabak (2012) therefore suggested that encouraging parties to send a letter would be more empowering than suggesting that they wait for one. However, MacKay (2014) notes that only about 14 per cent of donor families who received a letter wrote one back.

MacKay (2014) suggested that organisations should identify barriers to correspondence, develop and implement solutions and provide workshops and individual assistance where required to improve the rate of correspondence. Leverage points that have been identified with regard to the potential to increase correspondence rates include making parties aware of the value of correspondence, empowering recipients by reducing feelings of unworthiness or assisting those who have concerns regarding their writing abilities, ensuring recipients that donor families appreciate letters and writing will not cause the family further harm, providing a clear process to facilitate correspondence and reducing legal or policy-related matters that may inhibit contact (Colarusso, 2006; MacKay, 2014).

For example, donor families and recipients felt that organisations should forward their correspondence without being able to delete parts or choose not to forward certain letters. In cases where there are specific concerns, participants felt that the organisation should share these with the writer and allow a rewrite or the decision to send as is (Politoski et al., 1996). Martin (2017) reports that parties requested some form of confirmation that anonymous correspondence was received.

Albert (1999) argued that the stakeholders should be allowed to decide what information they want to share with the other party and whether they want to make contact, pointing out that if consent to the sharing of information and contact was provided in written form, organisations would be relieved of the responsibility of protecting parties. Challenging ideas of vulnerability, Colarusso’s (2006) study demonstrates that if organisations were to directly encourage recipients to write an initial letter, recipients would not feel that they had been placed under too much pressure and more would write letters of thanks.

Direct contact

Christopherson and Lunde (1971) reported on two cases where a meeting between the donor family and the recipient was coordinated. All parties expressed positive feelings and found the meetings meaningful. Centres in the United States and Israel support the rights of donor families and recipients to have direct contact if they choose to, and Lewino et al. (1996) argue that when both parties demonstrate an interest in meeting, the outcome is not negative.

The most effective meetings are preceded by anonymous contact between the parties (Clayville, 1999) which helps to clarify matters and answer questions. Researchers have found that parties see health professionals as having a role in facilitating this gradual contact (Ashkenazi, 2013; Azuri and Tabak, 2012; Corr et al., 2011; Holtkamp, 2002; Lewino et al., 1996; Vajentic, 1997; Willis and Skelley, 1992). Kandel and Merrick (2007) found that most of those who were able to meet considered it a positive experience and did not feel that the health professionals were responsible for the outcome of the meeting (Azuri and Tabak, 2012; Landon, 2004; Vajentic, 1997).

Nevertheless, in addition to theoretical explanations, perceived advantages or disadvantages of particular actions and the application of guiding principles, healthcare professionals providing support to donor families and recipients need to be willing to reflect on their own beliefs and values and consider how these may influence their objective of facilitating informed decisions (Azuri and Tarabeih, 2018).

Azuri and Tabak (2012) found that more donor families (67%) than recipients (29%) had initiated contact and most of those who had made contact felt satisfied that it had gone well and many were interested in further contact.

Families who met with recipients reported that the meeting eased their pain, contributed to positive meaning in their loss (Azuri et al., 2013) and facilitated a sense of calm, satisfaction (Kandel and Merrick, 2007), peace and closure (Albert, 1999; Lewino et al., 1996). Having their pain acknowledged and seeing the gratitude of the recipient was helpful to families (Shih et al., 2001), as was the experience of seeing the difference that their decision had made in other’s lives. Some families felt that their decision was validated by evidence that it had facilitated the recipient’s health, and this assisted family members to organise their lives and focus on their future (Clayville, 1999).

Ashkenazi (2013) found that donor parents who met recipients of their children’s organs found increased meaning in donation, and it was concluded that for parents who wanted contact with recipients, a meeting was a very meaningful experience.

At the same time, recipients used contact as a way of expressing gratitude and reported a reduction in feelings of guilt. Goetzmann et al. (2009) even found that this was related to a more successful recovery from surgery.

In some countries, the law prevents healthcare professionals from facilitating direct contact between donor families and recipients. Where the desire for contact is strong, these donor families and recipients may consider their own ways of addressing their needs. In Australia, Donor Families Australia (DFA, an organisation representing families of organ and tissue donors) has found that many of its members feel that contact should be possible if both parties are willing and able to make an informed decision (Mazur, 2017). DFA members who have been able to make contact have generally reported that meeting recipients has been a positive experience characterised by gratitude and healing. In response, DFA manages a Donor Family–Recipient Contact Register that enables parties wishing to make contact to provide their details so that DFA can identify matches (Donor Families Australia, Inc., 2018).

Secondary losses

In reaction to their bereavement, individuals and families often seek a continued psychological connection with the deceased while accepting their death (Corr et al., 2011).

In the organ donation context, this may be linked to thoughts about recipients and secondary losses could take a unique form because parts of a deceased relative are alive inside other people. Hence, researchers have described the risk that the donor family may experience a secondary loss if the organ is rejected or the recipient dies (Corr et al., 2011; Holtkamp, 2002).

When trying to understand this reaction, Corr et al. (2011) noted that families’ continuing bonds with their loved ones could come to depend on relationships with recipients rather than existing as internal representations. In this way, the transplanted organ or the recipient may have come to play a significant role in the family’s adjustment to their loss. This is congruent with findings that reliance on a sense that the donor is ‘living on’ is associated with an increased risk of complications in bereavement (Christopherson and Lunde, 1971; Holtkamp, 2002; Pittman, 1985). According to Corr et al’.s (2011) hypothesis, the death of a recipient severs the family’s bond with a part of their relative and results in emotional pain that may be similar to that experienced when their relative died.

Staff need to create a supportive and respectful environment and take the time to understand the emotions, beliefs, resources and motives of parties to identify where further information and emotional support would assist the balancing of benefits, risks and expectations and contribute to the emergence of an informed decision about contact that is in the interests of the parties involved rather than simply the result of the application of rigid rules (Azuri and Tarabeih, 2018).

Researchers urge that donor families who contact recipients should be informed about the possibility of secondary losses and provided with appropriate support (Corr et al., 2011; Holtkamp, 2002). When considering the reduction of risk related to secondary losses, Corr et al. (2011) suggest that those providing support should avoid referring to the deceased as ‘living on’ and rather focus on the hope and quality of life that the recipient has following transplantation.

Risks and protective factors

Wright et al. (2012) obtained mixed results regarding recipients’ contact with donor families. On one hand, recipients who had made contact with their donor’s family reported that it had been a positive experience, but statistical analysis showed that making contact predicted higher rates of somatic–affective depressive symptoms. Wright et al. (2012) concluded that further research would contribute to better understanding of these variables.

Albert (1999) reports that some donor families, recipients, transplant centres and donation agencies have expressed concern about the possible loss of control if anonymity is not enforced. For example, one party may desire or demand more contact than is comfortable for the other.

Researchers feel that exaggerated expectations contribute to the risk of disappointment which may influence coping when contact is made and either party does not meet the expectations of the other (Albert, 1998; Corr et al., 1994; Holtkamp, 2002; Holtkamp and Nuckolls, 1991, 1993). Some information about the other party and their coping could contribute to realistic expectations before making contact (Azuri and Tabak, 2012) and reduce this risk.

Holtkamp (2002) feels that the bereavement of donor families may be complicated if their wish for contact or lack thereof is not shared by the recipient and/or their family. In such a case, lack of contact could be perceived as indicating lack of appreciation.

Donor families could find it difficult to reconcile their loss and the recipient’s improved quality of life (Albert, 1999), and differences of opinion within families on each side could contribute to intra-family tension (Kandel and Merrick, 2007; Martin, 2017).

To identify cases where connection to the recipient poses a risk to healthy bereavement, Holtkamp (2002) suggests that the combination of impulsive inquiry, obsessive searching behaviours and an inability to accept the death of the donor should be seen as indicative of high risk.

Clayville (1999) reported that families provided the following advice about the contact process: the timing of the meeting and having a neutral intermediary is important; it is useful if families have reached a point of readiness in their grieving before meeting; some suggested that meetings should be private, away from the media, but with a professional to assist if necessary; donor families appreciate the ability to talk about their loved one and getting to know the recipient can validate their decision.

Researchers agree that if contact was to be allowed, it should follow a ‘cooling off’ period after donation/transplantation and be facilitated by a healthcare professional in a controlled environment (Azuri et al., 2013; Gewarges et al., 2015).

Professionals should provide support when vulnerabilities present themselves. To identify such vulnerabilities, Holtkamp (2002) suggests that in a supportive environment matters such as the sense of connection with recipients could be explored together with an assessment of the family/family member’s adjustment to loss and attachment to the donor.

These observations show the extent of any risk could be related to several factors. For example, it has been noted that families should have reached a point in their bereavement that makes them ‘ready’ to consider meeting recipients. This implies that there is a period before this when the family is not ‘ready’, and emotional and social resources may be insufficient to enable them to cope with the emotional demands of meeting. It also implies that the potential risk experienced by a specific family will vary over time, highlighting the need for a skilled moderator to assist with the process.

Some considered the risk of there being no contact and felt that when contact between donor families and recipients was forbidden, there was a denial of the way that their lives have become connected. It was argued that by restricting the sharing of information about the recipient, the outcome of the donor family’s decision is denied or silenced, contributing to frustration (Robertson-Malt, 1998).

Among those recipients who had had contact with donor families, some expressed concerns about the level of involvement desired by the donor family (Peyrovi et al., 2014), an excessive sense of responsibility to ensure that the transplanted organ is protected (Azuri and Tabak, 2012) or found that religious or social differences could contribute to stress (Albert, 1998).

Olson et al. (1992) argue that because a meeting between a donor family member and recipient has the potential to initially contribute to confusion and strong emotions, meetings should be monitored to ensure that everyone’s needs are respected.

A healthcare professional facilitating a first meeting between a donor family and recipient should be aware of each party’s expectations before the event, and where appropriate take steps to ensure that they are realistic. Providing clear structure to the meeting in terms of a specific time and place as well as information about items or gifts that would be appropriate/inappropriate (e.g. photos, chocolates) is useful to participants, as is assistance in the management of post-meeting expectations.

Apart from a desire to contact the persons involved in the same donation–transplantation event, donor families and recipients at times show an interest in attending Services of Remembrance, the Transplant Games, awareness campaigns and other events where they can meet other donor families and recipients. Recipients can celebrate their health and give thanks to donor families in general, while donor families can see the difference that decisions such as theirs have made in the lives of recipients (Jensen, 2007; Maloney, 1998; Schweda and Wohlke, 2013).

Vajentic and Calovini (2001) report on a support group programme where members of donor families benefitted from sharing experiences with those who had had similar experiences, regaining hope for their future by seeing others surviving. Likewise, several recipients reported that they engaged in self-help groups or participated in organ donation campaigns as a way of ‘repaying’ or compensating for the opportunity to live (Schweda and Wohlke, 2013).

Section 5: views of health professionals, donation agencies and transplant centres

Traditionally, it has been the role of transplant and organ procurement professionals to determine the type and frequency of information or contact that should be allowed between donor families and recipients (Politoski et al., 1996).

Over the years, organisations have produced documentation to make donor families and recipients aware of the benefits and methods of anonymous correspondence in the hope that this option will be more widely used (Maryland Nurses Association, 2006; Mehakovic and Bell, 2015; National Donor Family Support Service Framework Australian Organ and Tissue Authority, 2011; Thanking Your Donor Family, 2018).

The guidelines used by the National Health Service (NHS) to encourage recipients to write a Thank You letter (Thanking Your Donor Family, 2018) are congruent with research described earlier (Azuri and Tabak, 2012) in that recipients are made aware that ‘… donor families state that they would like to hear from the person who received their loved one’s donation …’ (p. 2) and ‘… Donor families have made the brave decision to support donation because they want their loved one to save others. Your news will show they have achieved this and most take great comfort from that knowledge’ (p. 4).

These words reflect Bartucci and Seller’s (1988) suggestion 30 years earlier that transplant centres should not remain neutral but should encourage recipients to write to their donor families. This encouragement seems appropriate given that researchers have found that most donor families and recipients are satisfied with anonymous correspondence as a way of communicating (Annema et al., 2013; Larson et al., 2017; Vajentic, 1997) even when the option of direct contact is available.

For those who desire more than anonymous contact, the response of centres across the world has varied with some providing carefully considered avenues to direct contact (Landon, 2004; Larson et al., 2017; Vajentic, 1997) and others believing that anonymous contact should remain the norm (Annema et al., 2013). However, as described by Christopherson and Lunde (1971), Robertson-Malt (1998), Holtkamp (2002) and others, there has always being a portion of the donor family and recipient population that will not be satisfied with their options being restricted.

Politoski et al. (1996) conclude that donor families and recipients have a right to information and contact if mutually desired and argue that organisations must act to facilitate that right to connect in order to allow the healing aspects of this relationship to be experienced.

However, donor families and recipients are sometimes seen as vulnerable groups that could easily experience harm and therefore need to be protected from each other (Ono et al., 2008). When this position is taken, authority figures could be expected to do nothing rather than risk doing something wrong (Albert, 1998, 1999; Corr et al., 1994).

Rather than focus on vulnerability, Albert (1999) explored the matter of contact between donor families and recipients with reference to ethical principles. Considering autonomy, Albert (1999) highlighted the right to self-determination and the responsibility of healthcare professionals to facilitate salience including knowledge of risks and benefits contributing to informed decision-making (Maloney, 1998; Ono et al., 2008). Beneficence requires the healthcare provider to take a holistic approach to care to ensure that their impact on others is positive.

In this environment where ethical dilemmas will arise, professionals should receive training in bioethics and use simulations to prepare them for their role in a process where principles such as autonomy and beneficence are not always easy to balance (Azuri and Tarabeih, 2018).

Politoski et al. (1996) argued that organisations should develop clear and fair guidelines regarding direct contact to ensure consistency and then conduct research to determine the appropriateness of these guidelines. This is vital today because, as argued by Martin and Mehakovic (2017), direct contact between donor families and transplant recipients is an issue that can no longer be overlooked.

Evidence of the value of such an approach has been demonstrated in this context: Since the 1980s, procedures like those described by Bartucci and Seller (1986, 1988) have been used to facilitate anonymous contact, enabling researchers to investigate the benefits and risks involved. Mehakovic and Bell (2015), for example, report that research conducted by the Organ and Tissue Authority (OTA) in Australia indicated that donor families found receiving letters from recipients comforting, confirming the positive impact of their donation decision.

In response, OTA is confidently exploring ways of actively encouraging recipients to write Thank You letters to donor families based on evidence that the organisation trusts (Mehakovic and Bell, 2015).

With the availability of social media and Internet search engines, it is not difficult for donor families and recipients to identify each other if they try. Considering this, a re-examination of practices is required to ensure that policies are appropriate in the present (Gewarges et al., 2015; Northam, 2017).

In addition to preparing donor families for their ongoing adjustment to loss, and transplant recipients for their adherence to medical treatment post-transplant, organisations now have a responsibility to educate parties about social media and online etiquette.

The NHS in the United Kingdom (Tolley, 2018b) and other centres (Media, Social Media and Your Transplant, 2018) have developed guidelines for the use of social media aimed at educating parties regarding the potential benefits and risks of social media use. Martin (2017) highlights the need to provide similar guidance to donor families and recipients in Australia who make use of social media or are independently seeking direct contact.

OTA recently facilitated a Community Consultative Forum, inviting stakeholders from donor family and recipient groups to discuss the matter of contact between the parties (Martin, 2017). The need to develop policies and strategies that protected core values such as privacy while providing opportunities for people to act on their own informed choices was highlighted.

Martin (2017) concluded that because there is diversity in needs and perspectives among the parties involved, no single response will be satisfactory to everyone. It was suggested that principles such as compassionate, supportive care for donor families and recipients and facilitating opportunities to share information and experiences that celebrate the donor as a person should guide decision-makers. Mazur (2017) reported on the same forum from the perspective of the donor families and recipients present and highlighted risks, benefits and ways of managing contact (such as an online portal with filters to remove identifying details and ensuring awareness of social media privacy settings) that could balance the need for confidentiality with the need for contact.

As in the United Kingdom (Tolley, 2018a), it was considered useful to take the immediate step of improving present systems of anonymous correspondence while considering the implications of legal changes that would be required to allow direct contact to be explored (Martin, 2017).

Analysis

Schweda and Wohlke (2013) suggest a move away from seeing organ donation as a one-directional act to acknowledging its social nature. This implies that the donor family story and the recipient story are parts of another more comprehensive story. As an analogy, if the actions of a pair of dancers were viewed independently while considering how they complement each other, one could obtain information about the nature of the dance that they were performing.

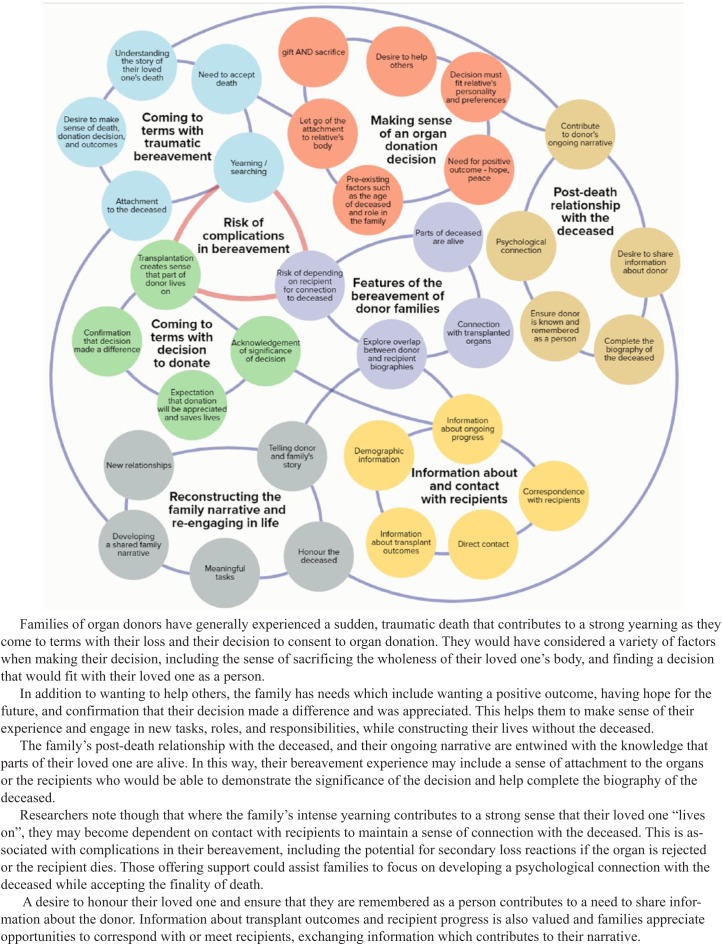

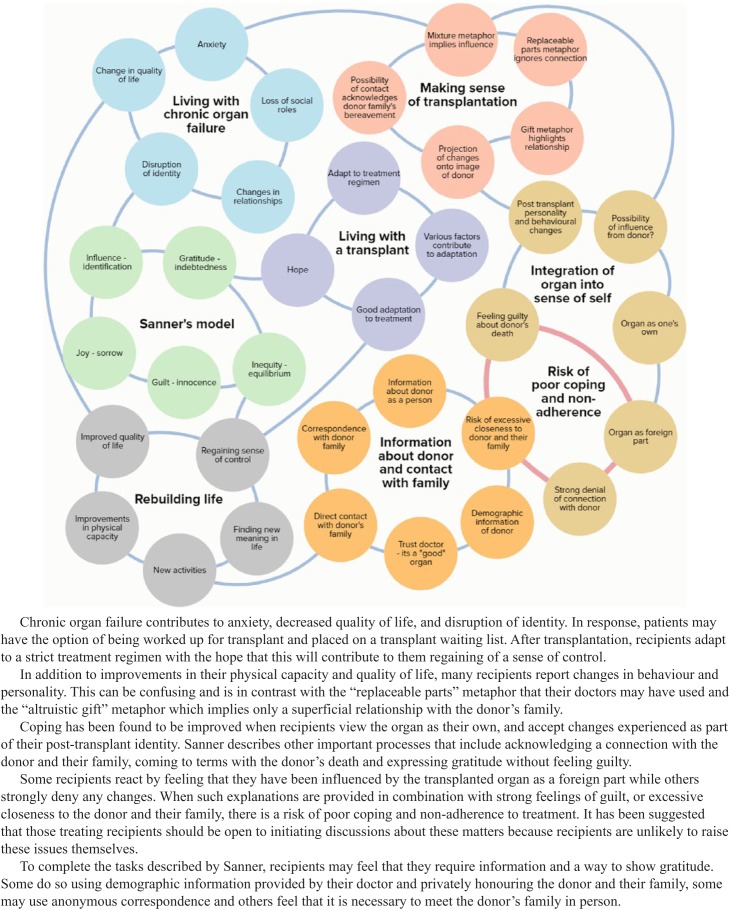

The extracted data described in Sections 1 and 2 are summarised in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. Comparing these summarised narratives of donor families and transplant recipients, several similarities are evident. These similarities strengthen the possibility that the two stories together will illuminate another story of which the original stories are each a part. According to Bateson’s ([1972] 1987, 1979) claims about double description, this third story will also include ‘bonus’ information about the relationship between the participants. The analysis that follows will demonstrate this.

Figure 2.

Experiences and challenges of families of deceased organ donors.

Figure 3.

Experiences and challenges of organ transplant recipients.

Donor families and recipients each faced crises and made extraordinary decisions – for the donor family, to donate a relative’s organs, and for the recipients, to have an organ transplanted into their body in the hope of improving their lives. Following these decisions, parties need to make sense of the implications of their choices.

Both faced death and hoped for life. During their time at the hospital, when they realised that life was not possible for their relative, families who decided to consent to donation may have developed hope that recipients would benefit. This may have altruistic features and also be part of the family’s search for a meaningful outcome to their crisis.

These life and death struggles in the context of organ donation and transplantation could contribute to the emergence of mutual empathy, hope and a sense of connection between donor families and recipients. Neither can ignore the existence of the other because without the other the events surrounding organ donation and transplantation would not have taken place.

In both cases, the metaphors used by organisations and healthcare professionals are not comprehensive enough to capture the experience, potentially contributing to mistrust and a feeling of being misunderstood. It is proposed that to resolve this incongruence, donor families and recipients turn to each other.

A mutually beneficial relationship may arise between parties who were strangers before. The recipient’s health assists the donor family to make meaning amid their loss, while the donor family, by consenting to donation, provides the recipient with an opportunity to live. The parties shape each other’s experience in ways that are unique to this context.

When the stories are brought together, a story of human endurance and overcoming of obstacles emerges. A key feature of the shared experience is the importance of relationships with the deceased.

Both donor families and recipients need to clarify their relationship with the donor to make sense of their experiences. The donor family needs to complete the biography of the deceased and make peace with their decision to consent to donation, and the recipient needs to acknowledge the role that the donor and their family played in saving their lives and make peace with having a part of the donor sustaining their ongoing life while not feeling guilty.

When exploring relationships with the donor, the donor family can provide the recipient with information about the donor’s life and personality, and the recipient can provide information about their own coping and gratitude which assists the donor’s family to continue their narrative and that of the deceased. This is relevant because donation and transplantation contribute to an overlap in the narrative of the donor and their family and that of the recipient and their family.

Considering Bateson’s ([1972] 1987, 1979) thoughts about feedback loops and patterns that connect when relationships are formed, we wondered what the nature of the feedback sought by the parties was, what this meant to them and how it would help explain their drive for contact.

Researchers report that recipients had questions and experiences that they did not share with others, and we wondered whether the same would be true for donor families. We noticed that although researchers have reported that donor families seek acknowledgement of the value of their decision, no clear explanation is given regarding why this would be important to them.

Organ donation decisions are made at an extremely stressful time when impaired concentration (Corr and Coolican, 2010), time pressure and unfamiliar circumstances (such as brain death) contribute to further stress (Siminoff et al., 2001). Given these variables, it is not surprising that several families report ambivalence regarding their final decision (Kesselring et al., 2007) with some experiencing regret (Burroughs et al., 1998; Rodrigue et al., 2008) which may contribute to complications during their bereavement (De Groot et al., 2012).

As described, several researchers have found that deciding about organ donation is not easy, and this would imply that family members probably continue to evaluate their decisions in the months that follow. We hypothesise therefore that one of the missing questions in the accounts of donor families could be ‘Have we done the right thing?’ While those proposing the gift metaphor might say, ‘Of course you have done the right thing, you are heroes!’, the sense of pain and sacrifice that families have described may make this an unsatisfactory answer.

Where the donor had registered their donation preferences, families can have some certainty that they decided as their relative would have wanted them to. Even then though, they may wonder whether their relative was fully aware of the implications of organ donation. For those families who were unsure of the donor’s wishes, or their own attitude towards donation, or found the decision particularly difficult for another reason, further evidence that their decision was suitable would be required so that it can be incorporated into their identity and narrative.

Steeves et al. (2001), from a constructivist point of view argue that people do not so much live their lives but tell themselves the story of their lives to make meaning and come to understand who they are. A death interrupts the narrative flow of life and challenges those remaining to adjust their narrative (Neimeyer et al., 2014).

Our working hypothesis would need to be tested, but if it were found to be valid, it would create balance in the stories of the struggles of donor families and recipients as described in Figures 2 and 3 by linking them both to relationship, identity, and narrative development.

According to this hypothesis, one of the reasons that donor families and recipients seek information about and contact with each other is to find an answer to the questions, ‘Who are we after deciding in favour of donation/transplantation?’ and ‘What are the qualities present in our post-death relationship with the donor as a result of this decision?’

Donor families would hope to be reassured (Pittman, 1985) that they made a decision that fits in their relationship with the deceased. Becoming aware of the difference that their decision made in the lives of recipients may assist with this (MacKay, 2014) and help them to find closure rather than ambivalence or regret.

These families would be able to feel confident about their decision and may identify themselves as families who made a difference. Those who knew that their relative would have been in favour of organ donation would be able to add to this that they honoured their loved one’s wishes, and those who made a shared decision may view the family as close and cohesive. In these ways, the family’s decision about donation and their knowledge of recipient progress contributes to their emerging post-loss identity.

In addition to being able to express their gratitude, recipients would hope that their transplant is not going to substantially change who they are as a person and they would benefit from knowing that the donor family is pleased that they are well so that they can let go of feelings of guilt.

We hypothesise that the third story emerging from the combination of the separate donor family and recipient stories is a story of mutual empathy and working together to build resilience and endurance in the face of significant crises while experiencing psychological and emotional growth, development in identity and a post-death relationship with the deceased. This story is reflected in the question, ‘Who are we now?’. This question is equally valid for donor family members and recipients. It connects their stories (Figures 2 and 3) and represents the ‘bonus information’ described by Bateson ([1972] 1987, 1979).

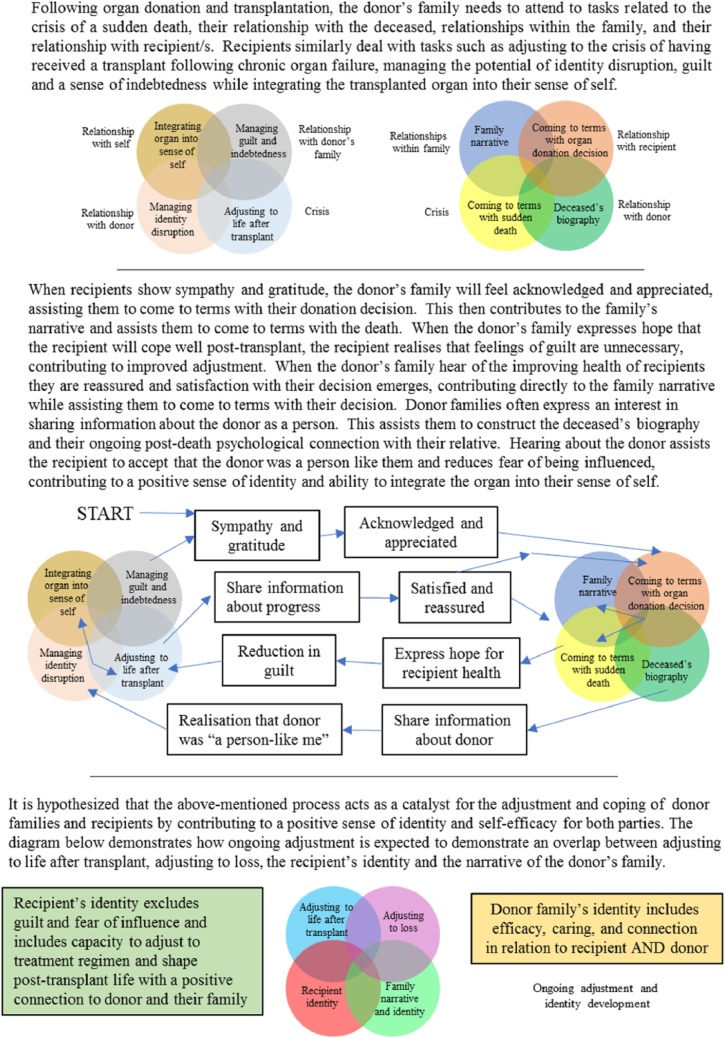

Figure 4 demonstrates this double description graphically, showing how the actions and experiences of donor families and recipients are linked and how they contribute to the relationships between the parties themselves and between the parties and the donor. Where the processes described in Figure 4 proceed in an ideal manner, aspects of the identities of the recipient and the donor family emerge in ways that facilitate further adaptation to their respective crises with a sense of endurance and efficacy. At the same time, aspects of the deceased’s post-death identity, the conclusion of their biography and the psychological relationships between the recipient/s, donor family and the deceased are shaped and may develop in ways that exclude guilt or regret and include honour, respect and a positive legacy.

Figure 4.

The combined narrative of organ recipients and families of organ donors.

Discussion

The previous section has provided hypotheses regarding the motivations that donor families and recipients have for considering contact with each other. These hypotheses can be seen as abstractions derived from the ‘concrete’ data and views expressed in the sources consulted. To be useful, these abstractions need to be embedded in new procedures that assist the system to evolve in response to the needs of donor families and recipients.

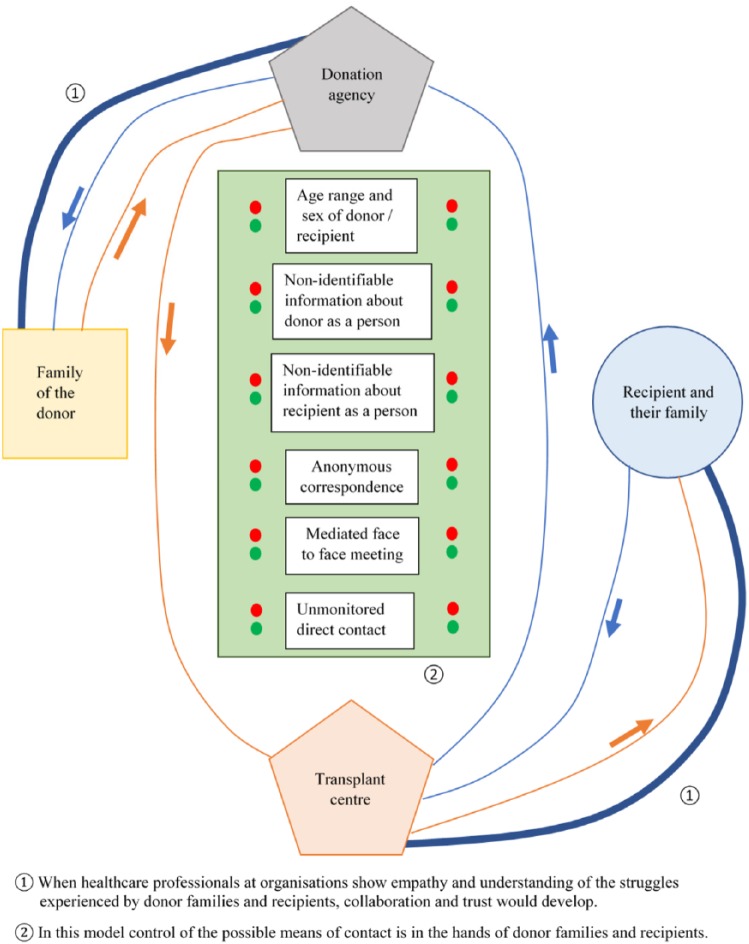

Contact between donor families and recipients is generally mediated in some way by organisations such as donation agencies and transplant centres that act with caution given the risks that have been identified (shown by the zones connected by red lines in Figures 2 and 3). In addition to the protection of individuals, organisations may also be considering the protection of the organ donation–transplantation system in that if contact was allowed and contributed to complications in bereavement for donor families and non-adherence for recipients, the system as a whole would be threatened.