Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) led to 887,000 human deaths in 2015. HBV has been coevolving with mammals for millions of years. Recently, the Smc5/6 complex, which has essential housekeeping functions, was identified as a restriction factor of human HBV antagonized by the regulatory HBx protein. Here we address whether the antiviral activity of Smc5/6 is an important evolutionarily conserved function. We found that all six subunits of Smc5/6 have been conserved in primates, with only Smc6 showing signatures of an “evolutionary arms race.” Using evolution-guided functional analyses that included infections of primary human hepatocytes, we demonstrated that HBx proteins from very divergent mammalian HBVs could all efficiently antagonize Smc5/6, independently of the host species and sites under positive selection. These findings show that Smc5/6 antiviral activity against HBV is an important function in mammals. They also raise the intriguing possibility that Smc5/6 may restrict other, yet-unidentified viruses.

KEYWORDS: hepatitis B virus, HBx, restriction factor, antagonism, Smc5/6 complex, virus-host interaction, evolution of virus and host genes, positive selection

ABSTRACT

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of liver disease and cancer in humans. HBVs (family Hepadnaviridae) have been associated with mammals for millions of years. Recently, the Smc5/6 complex, known for its essential housekeeping functions in genome maintenance, was identified as an antiviral restriction factor of human HBV. The virus has, however, evolved to counteract this defense mechanism by degrading the complex via its regulatory HBx protein. Whether the antiviral activity of the Smc5/6 complex against hepadnaviruses is an important and evolutionarily conserved function is unknown. In this study, we used an evolutionary and functional approach to address this question. We first performed phylogenetic and positive selection analyses of the Smc5/6 complex subunits and found that they have been conserved in primates and mammals. Yet, Smc6 showed marks of adaptive evolution, potentially reminiscent of a virus-host “arms race.” We then functionally tested the HBx proteins from six divergent hepadnaviruses naturally infecting primates, rodents, and bats. We demonstrate that despite little sequence homology, these HBx proteins efficiently degraded mammalian Smc5/6 complexes, independently of the host species and of the sites under positive selection. Importantly, all HBx proteins also rescued the replication of an HBx-deficient HBV in primary human hepatocytes. These findings point to an evolutionarily conserved requirement for Smc5/6 inactivation by HBx, showing that Smc5/6 antiviral activity has been an important defense mechanism against hepadnaviruses in mammals. It will be interesting to investigate whether Smc5/6 may further be a restriction factor of other, yet-unidentified viruses that may have driven some of its adaptation.

IMPORTANCE Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) led to 887,000 human deaths in 2015. HBV has been coevolving with mammals for millions of years. Recently, the Smc5/6 complex, which has essential housekeeping functions, was identified as a restriction factor of human HBV antagonized by the regulatory HBx protein. Here we address whether the antiviral activity of Smc5/6 is an important evolutionarily conserved function. We found that all six subunits of Smc5/6 have been conserved in primates, with only Smc6 showing signatures of an “evolutionary arms race.” Using evolution-guided functional analyses that included infections of primary human hepatocytes, we demonstrated that HBx proteins from very divergent mammalian HBVs could all efficiently antagonize Smc5/6, independently of the host species and sites under positive selection. These findings show that Smc5/6 antiviral activity against HBV is an important function in mammals. They also raise the intriguing possibility that Smc5/6 may restrict other, yet-unidentified viruses.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infects more than 250 million people worldwide and is a leading cause of chronic hepatitis and liver cancer in humans (http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b). HBV is a member of the Hepadnaviridae family of DNA viruses, which have coevolved with their host species for millions of years (1–3). Today, hepadnaviruses are found to naturally infect, in a species-specific manner, mammals, birds, fish, and amphibians. In mammals, HBVs are present in rodents, bats, and several primates, including humans, chimpanzees, gibbons, orangutans, and New World wooly monkeys. Mammalian hepadnaviruses (orthohepadnaviruses) all contain a gene encoding a small regulatory protein, the X protein or HBx, that is thought to have arisen de novo in the orthohepadnavirus lineage (1). HBx has long been known to play a central role in HBV replication and pathogenesis (4–6) and has recently been shown to have a key role in promoting HBV transcription by antagonizing the restriction function of the infected cell's Structural Maintenance of Chromosome (SMC) Smc5/6 complex (7, 8). However, whether this property has been conserved among the HBx-containing hepadnaviruses is unknown.

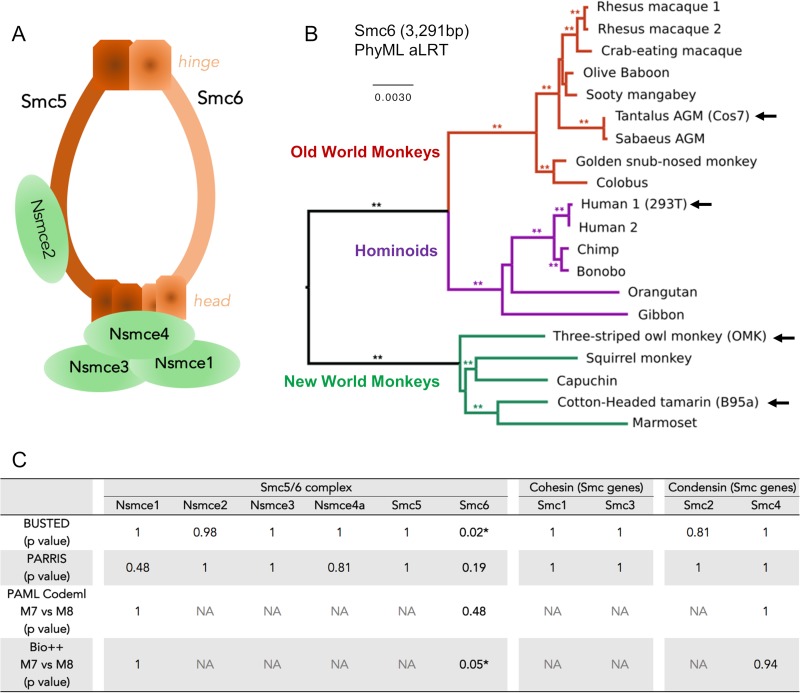

The Smc5/6 complex is, together with cohesin and condensin, one of the three SMC complexes found in eukaryotes (9, 10). As for the other SMC complexes, the core of the Smc5/6 complex is formed by a heterodimer of two SMC proteins, Smc5 and Smc6 (11), which associate with four additional subunits known as non-SMC elements (Nsmce1 to -4) (Fig. 1A). These SMC complexes all have essential housekeeping functions, playing fundamental roles in chromosome replication, segregation, and repair (reviewed in reference 10). Condensin controls chromosome condensation during mitosis, and cohesin maintains cohesion between the newly replicated sister chromatids. The role of the Smc5/6 complex is less well understood. It has reported functions in DNA replication and repair, but its exact mode of action remains elusive (12–16).

FIG 1.

Smc6 is the least conserved subunit of the Smc5/6 complex in primates. (A) Architecture of the Smc5/6 complex. The complex is made of two core subunits (Smc5 and Smc6) and four non-SMC elements (Nsmce1 to Nsmce4). (B) Phylogenetic analysis of primate Smc6 genes. Sequences were aligned with MUSCLE and phylogeny was performed with PhyML and an HKY+I+G model with an approximate likelihood ratio test (aLRT) as statistical support (**, aLRT > 0.8). Newly sequenced genes (arrow) are indicated. The newly sequenced Smc6 gene from Chlorocebus pygerythrus (vervet African green monkey [AGM] Vero cells) is not represented because the nucleotide sequence is identical to the retrieved Chlorocebus sabaeus (Sabaeus AGM) sequence of Smc6. Alignments and phylogenies of the 10 analyzed SMC genes are available in supplemental data set 1 at https://figshare.com/articles/DatasetS1_Host_gene_alignments_used_in_the_study_fasta_format_and_phylogenetic_analyses_newick_format_Nsmce1-4_Smc1-6/6194813. (C) Positive selection analysis of the indicated genes during primate evolution. Shown are the P values obtained using four different methods (BUSTED, PARRIS, PAML Codeml, and Bio++; see Materials and Methods). The P values of the maximum-likelihood tests indicate whether the model that allows positive selection better fits the data (*, statistically significant). NA, results are not available because convergence was not obtained for these genes and/or analyses (see Materials and Methods).

In addition to its essential cellular activities, a novel function of the human Smc5/6 complex as an HBV restriction factor has recently been uncovered: in the absence of HBx, the Smc5/6 complex binds to the HBV episomal DNA genome and inhibits viral transcription (7, 8, 17). Human HBx antagonizes this effect by hijacking the host DDB1-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase complex to target the Smc5/6 complex for ubiquitin-mediated degradation, thereby enabling productive HBV gene expression (7).

Most genes encoding antiviral restriction factors have been engaged in an “evolutionary arms race” with the viruses they inhibit (18, 19). Indeed, during long-term coevolution, pathogenic viruses and their hosts are constantly under the selective pressure of the other for survival. As a result, host restriction factors evolve rapidly and display signatures of positive (diversifying) selection. These signatures can be identified by analyzing the codon sequences of orthologous genes from a large number of related species. At virus-host interaction sites, one can witness adaptive changes, including frequent amino acid changes (where a higher nonsynonymous substitution rate [dN] than the synonymous rate [dS] is indicative of positive selection) and insertion/deletions (indels) or splicing variants as ways to modify the virus-host interface and to escape from viral antagonists (19–24).

To assess whether the antiviral function of the Smc5/6 complex has been evolutionarily important, we performed phylogenetic and evolutionary analyses of orthohepadnaviruses and host proteins in combination with functional assays. We found that all six subunits of the Smc5/6 complex have been highly conserved in primate evolution, with only Smc6 showing signatures of an evolutionary arms race. Because orthohepadnaviruses diverged millions of years ago and their HBx proteins have very little sequence homology, we then investigated the Smc5/6-antagonistic capacity of HBx proteins from six divergent orthohepadnaviruses from primates, rodents, and bats. We found that all orthohepadnavirus HBx proteins are efficient at counteracting the Smc5/6 complex, independently of the host species or amino acid variations at sites under adaptive evolution. This Smc5/6 antagonism is a strict requirement for the establishment of mammalian HBV infection, showing that the Smc5/6 complex has been an important immune defense against hepadnaviruses in mammals. Although it would need further investigations, our findings also raise the intriguing possibility that the Smc5/6 complex may restrict other, yet-unidentified pathogenic viruses.

(This article was submitted to an online preprint archive [25].)

RESULTS

Overall evolutionary conservation of the Smc5/6 complex in primates.

To trace the evolutionary history of the Smc5/6 complex, we compared the sequences of its six subunits in primates (Fig. 1). As a comparison, we also analyzed the evolutionary history of the other primate SMC genes. These include the Smc1 and Smc3 genes, which encode the core cohesin subunits, and the Smc2 and Smc4 genes, encoding the condensin core subunits. The sequences of these genes were retrieved from publicly available data sets (Table 1; see also supplemental data set 1 at https://figshare.com/articles/DatasetS1_Host_gene_alignments_used_in_the_study_fasta_format_and_phylogenetic_analyses_newick_format_Nsmce1-4_Smc1-6/6194813). To perform more robust phylogenetic and selection analyses, we obtained additional primate species sequences using reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) approaches (Table 1 and Fig. 1B; see also Materials and Methods). Overall, we included up to 20 simian primate species in our positive selection analyses to span 40 million years of evolution (26, 27). We found that the synteny of the genes was conserved during primate evolution, although some subunits had duplicated pseudogenes in a few primate species (see supplemental Fig. 1 at https://figshare.com/articles/Figure_S1_Synteny_conservation_of_Smc5_6_complex_genes_during_primate_evolution_/6194867). Among the core SMC proteins, the most conserved are the cohesin Smc1 and Smc3 subunits, which share 100% and 99.9% pairwise identity at the amino acid level in a simian primate alignment, respectively (see supplemental data set 1 at https://figshare.com/articles/DatasetS1_Host_gene_alignments_used_in_the_study_fasta_format_and_phylogenetic_analyses_newick_format_Nsmce1-4_Smc1-6/6194813). Smc6 was the least conserved SMC protein, with 97.4% pairwise identity in simian primates. Using the Genetic Algorithm for Recombination Detection (GARD) on the complete set of genes (28), evidence of recombination (GARD, P < 0.05) was found only for Nsmce3, and therefore subsequent phylogenetic and selection analyses were performed on both the whole Nsmce3 gene and the two identified Nsmce3 gene fragments (from bp 1 to 246 and bp 247 to 912). Phylogenetic analysis of the 10 genes showed that the gene trees derived from nucleotide alignments were largely in accordance with the accepted species tree from Perelman and colleagues (27) (Fig. 1B; see also supplemental data set 1 at https://figshare.com/articles/DatasetS1_Host_gene_alignments_used_in_the_study_fasta_format_and_phylogenetic_analyses_newick_format_Nsmce1-4_Smc1-6/6194813).

TABLE 1.

Primate species and sequences that we included in the evolutionary analyses of the SMC complexesa

The asterisks indicate the sequences newly obtained in this study. The total number of primate species (sp) and individuals (ID) included in each gene analysis is indicated at the bottom. The abbreviated species names are found in parentheses (i.e., three first letters of the genus followed by the three first letters of the species).

To assess whether the Smc5/6 complex and the Smc1 to Smc4 genes have experienced diversifying selection during primate evolution, we performed four types of positive selection analyses. First, we used the BUSTED method, which tests whether a gene has experienced positive selection on at least one site or one branch during evolution (29). Of the six Smc5/6 complex subunits and the four SMC genes from the cohesin and condensin complexes, only one, Smc6, showed gene-wide evidence of episodic positive selection (BUSTED, P < 0.05 [Fig. 1C]). These findings were confirmed using the PARRIS method, which also detects evidence of positive selection using a codon alignment (30), although the level of significance was not reached for the Smc6 gene (P = 0.19 [Fig. 1C]). Third, we ran the Codeml program from the PAML package (31) on our codon alignments to compare two models: one that allows positive selection at certain sites (M8, alternative hypothesis) and one that disallows positive selection (M7, null hypothesis). We then performed a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to examine which of the two models better fits our data. Overall, there was no convergence for 7 of the 10 genes because they were too conserved (see Materials and Methods for details), and no evidence of significant positive selection was found for the remaining genes (Fig. 1C). Finally, we used the Bio++ package from Guéguen et al. (32), which has two main advantages over PAML, to similarly test for evidence of positive selection (M7 versus M8 as implemented in Bio++). First, the DNA substitution models use nonstationary matrices, which allow nucleotide composition to change over time and therefore improve the fitting to real data (33). Second, the codon frequency better fits biological assumptions than is the case with PAML (32). Using Bio++, we obtained higher values of likelihood, and for Smc6, a model allowing positive selection was favored over a model that disallows positive selection (Bio++ M7 versus M8, P = 0.05 [Fig. 1C]). Overall, these studies show that the SMC genes for cohesin and condensin, as well as the six Smc5/6 complex subunits, have been highly conserved during primate evolution. This is similar to what has been described for the global evolution of SMC proteins in eukaryotes (9) and is consistent with their essential cellular housekeeping functions. However, it is in contrast to most other known antiviral restriction factors that have strongly evolved under positive selection in primates (18, 21). The only exception is the Smc6 gene, for which two positive selection analyses found evidence of adaptive evolution.

Evidence of site-specific adaptive evolution in primate Smc6.

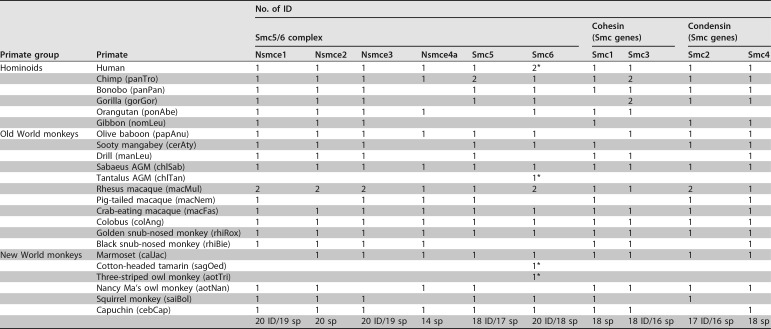

It is formally possible that most of the Smc6 protein has been highly conserved due to its housekeeping function, while just a few sites have been engaged in a virus-host interaction. Indeed, previous studies have shown that essential cellular proteins that are usurped by viruses for their replication have evolved under a strong purifying selection background, with only the virus-host interaction sites showing rapid evolution (34–38). To determine if this was the case for Smc6, we characterized in more detail its evolutionary history during primate evolution. Using the BranchSite-REL algorithm from HYPHY (39), we found that positive selection has occurred on a proportion of branches of the primate Smc6 phylogeny (episodic positive selection; BS-REL, P < 0.05). To look more specifically for site-specific positive selection, we used MEME and FUBAR, which are among the most accepted methods from HYPHY, as well as the posterior probabilities at codon sites in PAML and Bio++ (M8 model) (Fig. 2A). We confirmed that most codons in Smc6 have been extremely conserved, with over 90% having a ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous nucleotide (dN/dS) substitutions lower than 1 (Fig. 2B). However, a few sites were identified as having evolved under significant positive selection by one or several methods, consistent with site-specific positive selection in the primate Smc6 gene (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Evidence of episodic site-specific positive selection in Smc6 during primate evolution, as well as genetic plasticity in other mammals. (A) Specific sites in Smc6 are under positive selection. Codon alignments were analyzed using four different positive selection tests: MEME, which detects site-specific episodic positive selection; FUBAR, similar in a Bayesian framework; and Bio++ and PAML Codeml (M8), which detect site-specific positive selection (see Materials and Methods). The table shows the codon sites showing significant positive selection (i.e., that passed the widely accepted P value or posterior probability [PP] cutoffs for each method). The statistical thresholds used in each test are shown in the table. Codons identified as being under positive selection in at least two of the four tests are indicated by an asterisk. (B) Graphic depicting the proportion of sites in Smc6 at a given dN/dS ratio, calculated with BUSTED. A very low number of Smc6 sites are under positive selection. A dN/dS ratio of <1 indicates negative selection, a dN/dS ratio of 1 indicates neutrality, and a dN/dS ratio of >1 indicates positive selection. (C) Marks of genetic conflicts in Smc6. Sites under positive selection in primates as well as the plasticity of the N-terminal region of Smc6 in mammals are shown. Amino acid alignment was performed with MUSCLE, and residue color coding is from RasMol. A and B correspond to the globular domain that contain a Walker A and Walker B motif, respectively. Dashes indicate gaps. One nonprimate mammal species was arbitrarily chosen for the schematic representation. The mammal sequence illustrates only one possibility of the natural interspecies sequence variations that have been important in this region (see supplemental data set 3 at https://figshare.com/articles/Dataset_S3_Phylogenetic_analyses_of_Smc5_6_in_mammals_fasta_and_newick_format_/6194840 and supplemental Table 2 at https://figshare.com/articles/Table_S2_Species_used_for_the_phylogeny_of_the_mammalian_Smc6_and_for_the_experiments_/6194846). (D) Plasticity of the N-terminal region of Smc6 in bats. Truncated amino acid alignment (region from aa 20 to 47) of Smc6 sequences from bats. On the left is a cladogram of the bat Smc6. The amino acid alignment was performed with MUSCLE, and residue color coding is from RasMol (in Geneious [Biomatters]). Dashes indicate gaps.

In addition to single codon substitutions, other forms of genetic changes may also be adaptive in a virus-host arms race (21, 36, 40). In particular, recombination, gene deletion or duplication, and insertions and deletions (indels) can also be advantageous for the host. These “genetic innovations” would be missed in typical methods screening for positive selection. We found some indels in genes encoding several Smc5/6 complex subunits (see supplemental data set 1 at https://figshare.com/articles/DatasetS1_Host_gene_alignments_used_in_the_study_fasta_format_and_phylogenetic_analyses_newick_format_Nsmce1-4_Smc1-6/6194813). In particular, we found a 5-amino-acid (aa) indel in the N-terminal region of Smc6 (Fig. 2C). The five New World monkey species, including the two for which sequences were determined in this study, display a TASFT motif at this position. However, this 5-aa motif was not present in any of the retrieved Catarrhini species sequences (n = 13) (Fig. 2C, Hominoid and Old World Monk.).

To decipher if this 5-aa indel was specific to simian primates, we extended our analysis to mammals. We found a significant plasticity within this region with both indels and amino acid changes during mammalian evolution. For example, the prosimians' proteins contain a 5-aa motif, but with amino acid differences in the TASFT motif (TVSFT and AVAFT, respectively [Fig. 2C]). Another remarkable example of this N-terminal plasticity was found in bats (Chiroptera). Most bat species contain a 5-aa stretch (residues 36 to 40) but the sequence differs significantly (TVSFI, TVSFT, PDPFT, and TDTFT), while some bats carry an 8- to 10-amino-acid deletion within this region (Chinese horseshoe bat [Rhinolofus sinicus] and great roundleaf bat [Hipposideros armiger]) (Fig. 2C and D). Therefore, although most of the Smc6 protein sequence has been very conserved in primates and more generally in mammals, a few sites have been under significant positive selection and show substantial genetic plasticity. These signatures of genetic changes in an essential protein could be reminiscent of an evolutionary arms race with pathogenic viruses.

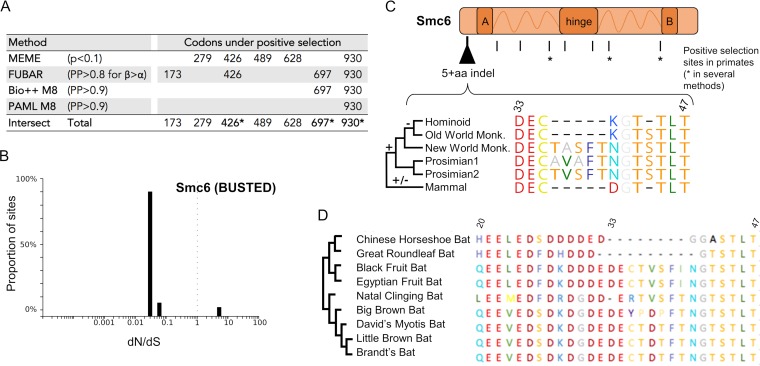

HBx and the woodchuck WHx counterpart promote degradation of diverse mammalian Smc5/6 complexes, independently of variations at genetic innovation sites.

We next used evolution-guided functional analyses to examine whether the marks of adaptive evolution and the identified interspecies variability of the Smc5/6 complex have functional consequences for the ability of HBx to promote its degradation. To test this, we put together a panel of mammalian cells encoding divergent Smc5/6 complexes and, importantly, with Smc6 orthologues with variations at positive selection sites and indels (Fig. 3A). This panel included cells derived from various primate species, including humans and the tantalus African green monkey (Chlorocebus tantalus), vervet African green monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus), and the New World owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus), as well as ferret (Mustela putorius furo, carnivore) and mouse (Mus musculus, rodent) cells. Using this panel, as well as different human cell lines, we tested the capacity of the human HBx and the woodchuck WHx counterpart to promote degradation of the heterologous Smc5/6 complex in these cells. Consistent with previous studies (7, 8), we found that HBx transduced in various human cell lines, including HepG2 (hepatocyte carcinoma), 293T (kidney epithelial), and HeLa (epithelial adenocarcinoma), triggers similar decreases in endogenous Smc6 and Nsmce4A protein levels (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained with the U2OS (human osteosarcoma) and A549 (human lung adenocarcinoma) cell lines (data not shown). This indicates that this HBx activity is neither cell type specific nor affected by human polymorphism at position 697 (NCBI dbSNP reference rs1065381).

FIG 3.

HBx and WHx can degrade the Smc5/6 complex in cells from diverse mammalian species. (A) Amino acid differences at the sites of genetic conflict in Smc6 between the host species tested for panels B and C. Note that all statistically significant marks of a potential evolutionary arms race identified in Fig. 2 are represented. Asterisks indicate the sites that were found under positive selection by at least two methods. (B) HBx from human HBV degrades the human Smc5/6 complex, independently of the cell type and the human polymorphism at position 697 (NCBI dbSNP reference rs1065381). Protein expression of endogenous Smc6 and Nsmce4A (two essential subunits of the Smc5/6 complex) from three human cell lines (HepG2, 293T, and HeLa cells) that were previously transduced with a lentivector expressing GFP only (GFP) or the HBx protein from human HBV fused to GFP (HBx) is shown. GAPDH serves as a loading control. (C) The human (HBx) and woodchuck (WHx) HBV X proteins promote degradation of the Smc5/6 complex in primate, rodent, and carnivore cells (n = 6 species). Cells were transduced with a lentivector encoding GFP alone, GFP-HBx, or GFP-WHx. The mouse Smc6 could only be detected using a different anti-Smc6 antibody (see Materials and Methods; the NIH 3T3 blots are from two SDS-PAGE loaded with the same cell lysates).

Then cells from the six different mammalian species were transduced with a lentivector encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) alone, GFP-HBx, or GFP-WHx. Five days later, we found that HBx and WHx expression had specifically triggered the degradation of the Smc5/6 complex in all species tested (Fig. 3C). This was true even for host species like the owl monkey, which harbors a 5-aa insertion in the N-terminal region of Smc6 (Fig. 2C and 3) and for Old World monkeys, which, in contrast to New World monkeys and hominoids, are not natural hosts for hepadnaviruses (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results show that the antagonism of endogenous Smc5/6 by the viral HBx and WHx is independent of the cell type and of the mammalian host species. Overall, amino acid differences at sites under adaptive evolution in Smc6 did not significantly impact HBx-mediated degradation of the complex (Fig. 3), suggesting that HBV has not driven Smc6 adaptation in primates.

Mammalian hepadnavirus HBx proteins show a conserved ability to counteract the restriction activity of the human Smc5/6 complex.

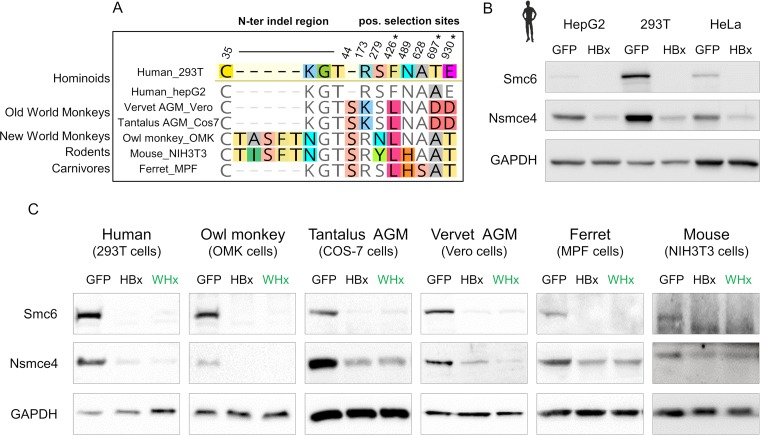

It is unknown whether the capacity to counteract the Smc5/6 complex is an important and conserved function of mammalian hepadnaviruses that diverged millions of years ago. To span the entire orthohepadnavirus evolutionary history, we examined, in addition to the human HBx and woodchuck WHx, the newly cloned HBx proteins from a hepatitis B virus that infects the New World wooly monkey (WMHBx) and from three viruses infecting distantly related bat species: Hipposideros cf. ruber (roundleaf bat), Rhinolophus alcyone (horseshoe bat), and Uroderma bilobatum (tent-making bat) (RBHBx, HBHBx, and TBHBx, respectively) (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, these HBx proteins have highly divergent amino acid sequences, with some regions sharing essentially no homology. Despite this low sequence identity and long-term divergence, all HBx proteins showed comparable abilities to trigger degradation of the human Smc6 and Nsmce4A proteins, when transduced in either HepG2 or 293T cells (Fig. 5A and B).

FIG 4.

Evolutionary analyses of divergent mammalian HBV X proteins. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of the X proteins from hepadnaviruses that naturally infect mammals. The viral X proteins tested in our in vitro functional assays (Fig. 5 to 7) are indicated by an asterisk. Phylogenetic analysis of orthohepadnaviral X proteins was performed using a 161-amino-acid alignment obtained with MUSCLE (see supplemental data set 2 at https://figshare.com/articles/DatasetS2_Orthohepadnaviral_HBx_amino_acid_alignment_interleaved_phylip_format_/6194825) and the tree was built with PhyML and a JTT+I+G model with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values (>800/1,000) are indicated at the nodes. The tree was rooted for representation purposes according to the work of Drexler et al. (52) (but the outgroup of orthohepadnavirus is still under debate [2]). The scale bar indicates the number of amino acid substitutions per site. We analyzed the X proteins from HBVs from the ground squirrel (GSHBV), arctic squirrel (ASHBV), and woodchuck (WHV), three bat viruses naturally infecting Hipposideros cf. ruber (roundleaf bat), Rhinolophus alcyone (horseshoe bat), and Uroderma bilobatum (tent-making bat), respectively (RBHBV, HBHBV, and TBHBV), wooly monkey HBV (WMHBV), human HBV, and HBVs from other indicated hominoids. (B) Amino acid alignment of the viral X proteins used for Fig. 5 to 7. The black-to-white gradient depicts high-to-low sequence identity (Geneious). The open reading frames (ORFs) overlapping with HBx are shown, as well as the DDB1-binding region in the human viral HBx protein (72).

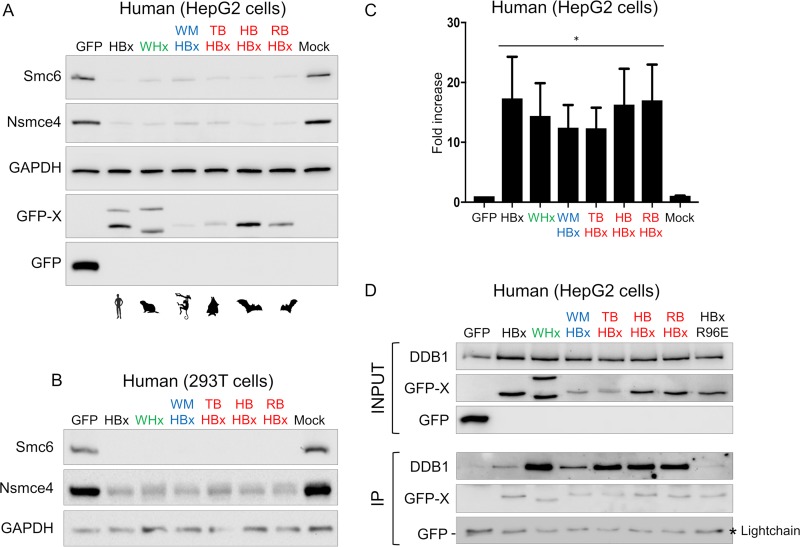

FIG 5.

Highly divergent mammalian HBV X proteins show a conserved property of recruiting human DDB1 and antagonizing human Smc5/6 restriction. (A and B) Degradation of the human Smc5/6 complex by mammalian hepadnavirus X proteins. Human hepatoma HepG2 cells (A) and 293T cells (B) were transduced with a lentivector expressing only GFP (control) or the GFP-fused X protein from diverse hepadnaviruses (Fig. 4) or a mock control. Western blot analysis of the endogenous Smc6 and Nsmce4A was performed (see Materials and Methods). GAPDH served as a loading control. (C) Effect of mammalian X proteins on transiently transfected reporter gene activity. HepG2 cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter construct and the next day transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing the indicated proteins as described above. At days 5 to 7, the luciferase activity was measured; the fold increase of relative light units (RLU) versus the GFP control condition (set at 1) is shown. The means from three independent experiments are shown, along with SDs. *, P value = 0.1. P values correspond to the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test against the null hypothesis of no difference in the luciferase activity between the GFP control and GFP-X conditions. Of note, the same six X proteins unfused to GFP (i.e., in their native forms) also retained this activity (data not shown). (D) Interaction with human DDB1 protein was conserved for all hepadnaviral X proteins tested. The presence of DDB1 and GFP-fused protein (IP) was assessed by Western blotting. The viral X proteins could all interact with human DDB1, except for the DDB1 binding-deficient HBx mutant (R96E) that was used as a control. Note that GFP migrates to a position near the immunoglobulin light chain.

Previous work has shown that the Smc5/6 complex binds episomal DNA templates to block transcription and that inactivation of the complex leads to an increased episomal gene expression (7). Accordingly, a similar increase in expression of a transiently transfected episomal luciferase reporter construct was observed in all orthohepadnavirus HBx protein-expressing cells (Fig. 5C). As an additional control, we constructed six vectors each expressing one of the six proteins in the absence of the fused GFP and found that the X proteins in their native form could all increase the expression of the luciferase reporter (data not shown).

Because the human viral HBx protein degrades the Smc5/6 complex by recruiting DDB1, we tested whether all X proteins were capable of interacting with human DDB1. Using coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments, we found that despite significant primary amino acid differences (Fig. 4B), the six mammalian hepadnaviral X proteins interact with human DDB1 protein (Fig. 5D). This suggests that the hepadnaviral X proteins antagonize Smc5/6 via a conserved molecular mechanism.

We finally tested whether this conserved capacity to degrade the Smc5/6 complex was restricted to only the human complex and found that the X proteins from human, woodchuck, monkey, and bat hepadnaviruses could also efficiently degrade the Smc5/6 complex in mouse and owl monkey cells (Fig. 6).

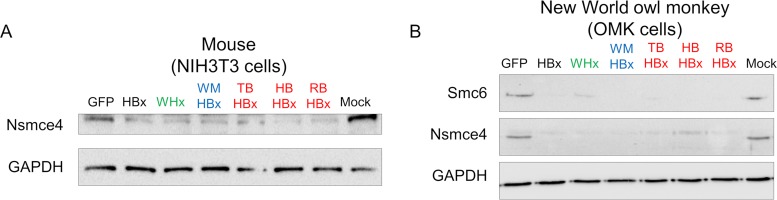

FIG 6.

Conserved capacity of hepadnavirus X proteins to degrade the Smc5/6 complex in mammalian cells from mouse and New World monkey. The same experiments as for Fig. 5 were performed with mouse NIH 3T3 cells (A) and OMK owl monkey cells (B).

Thus, the ability to degrade and to counteract the restriction activity of the Smc5/6 complex is conserved among mammalian hepadnavirus X proteins and in different species.

Divergent mammalian HBx proteins efficiently rescue replication of a human HBx-deficient hepatitis B virus in primary human hepatocytes.

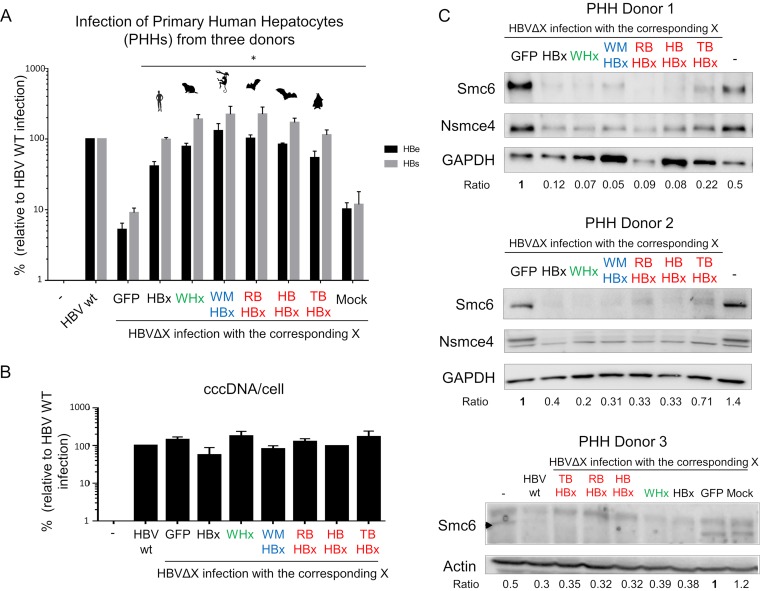

We finally tested whether the HBx proteins from nonhuman orthohepadnaviruses would substitute for human HBx in an HBV replication assay. Primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) were transduced with lentiviruses expressing GFP alone or fused to one of the six orthohepadnavirus HBx proteins and 4 days later infected with the wild-type HBV or an HBx-deficient HBV mutant (HBVΔX) (Fig. 7A). As shown previously, human HBx provided in trans fully rescued the replication defect of HBVΔX, as measured by HBe and HBs antigen secretion (7). Strikingly, the HBx proteins from the wooly monkey (WMHBx), woodchuck (WHx), and three bat (TBHBx, HBHBx, and RBHBx) viruses were all capable of restoring HBVΔX replication to levels comparable to those of wild-type HBV (Fig. 7A). This occurred in the absence of changes in viral covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) levels (Fig. 7B) and was accompanied by a concomitant decrease in Smc6 protein levels (Fig. 7C). These results provide functional evidence that orthohepadnavirus HBx proteins have a conserved capacity to antagonize the antiviral function of Smc5/6 and that this occurs in a species-independent fashion.

FIG 7.

The X proteins from six orthohepadnaviruses can all fully rescue the replication defect of an HBx-deficient HBV in primary human hepatocytes (PHHs). (A) PHHs were mock transduced or transduced with GFP or the indicated X proteins and infected with wild-type HBV or an HBx-deficient HBV (HBVΔX). HBe and HBs antigen secretion was quantified 7 days later by ELISA. Antigen concentrations are relative to wild-type HBV, which was set to 100. Data are means ± SEMs from independent experiments performed with three different PHH donors. *, P value = 0.1. P values correspond to the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test against the null hypothesis of no difference in the PHH infection between HBVΔX complemented with GFP alone and the GFP-X proteins. (B) The HBV cccDNA levels were measured at day 7 postinfection by real-time PCR. Values are expressed relative to beta-globin mRNA levels to normalize to cell number. The results are the means ± SEMs for the levels seen in PHHs from two donors. (C) Smc6 degradation in PHHs expressing the X proteins from different hepadnaviral lineages. Protein extracts were prepared from the cells listed above (three different PHH donors), and Smc6 protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting. Actin or GAPDH served as a loading control. “Ratio” shows the relative protein expression level of Smc6 over the actin or GAPDH controls, normalized to the GFP condition (GFP, 1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the HBx proteins from mammalian hepadnaviruses, which diverged millions of years ago and have very little sequence homology, all have the capacity to degrade the Smc5/6 complex and to counteract its antiviral activity in a species-independent manner. The antiviral function of the Smc5/6 complex against hepadnaviruses has therefore been an important immune defense mechanism in mammals.

We traced the evolutionary history of the genes encoding the six components of the Smc5/6 complex, as well as the genes for the Smc1 to -4 core subunits of cohesin and condensin. We show that Smc1 to -4 and the Smc5/6 complex have been highly conserved in primates. The only exception is the Smc6 gene, which shows some signatures of adaptive evolution in primates and mammals. These include several sites under positive selection and insertion/deletion events during mammalian evolution, which could be reminiscent of a virus-host evolutionary arms race. To examine if HBV, which is currently the only virus reported to be restricted by the Smc5/6 complex, has contributed to shape the evolution of the complex, we tested several orthohepadnavirus HBx proteins for the ability to antagonize the Smc5/6 complex across species. We found that all the HBx proteins tested, including those encoded by distantly related bat HBVs, were equally efficient in antagonizing Smc5/6 in human and other mammalian cells. This conserved property suggests that the interaction between the Smc5/6 complex and HBx is independent of the sites under adaptive evolution that we identified in this study. Thus, HBx does not seem to have driven the evolution of Smc5/6 in primates and, more broadly, in mammals.

Overall, we did not identify strong signatures of positive selection in the Smc5/6 complex as typically found in other known restriction factors (18, 21, 40, 41). This is surprising given that the antagonistic relationship between HBx and Smc5/6 has been conserved in orthohepadnaviruses (this study) and has likely been played out over tens of millions of years (1). There are at least three possible explanations for this apparent inconsistency. First, Smc5/6 has an evolutionarily highly conserved architecture, and it performs fundamental functions in cellular genome maintenance and thus has likely evolved under strong purifying selection. This is in contrast to most other described restriction factors, such as APOBEC3G and TRIM5, that are dedicated to their antiviral intrinsic immune functions (41, 42). However, our findings show similarities both at the evolutionary and functional levels with the serine incorporator proteins SERINC3 and SERINC5. These cellular proteins were recently found to act as restriction factors against lentiviruses (43–46). Despite their antiviral function and their antagonism by the lentiviral Nef protein, SERINC3 and SERINC5 also show little evidence for positive selection (45). Like Smc5/6, the SERINC proteins have important cellular functions and are not part of the interferon signaling pathway. The Smc5/6 complex and the SERINC proteins may therefore fall into a separate category of restriction factors that have dual antiviral and essential cellular functions and therefore have limited evolutionary opportunities. In an extreme scenario, host proteins might not be able to “escape” from the viral antagonist, and it is likely that viruses have adapted to target such constrained host proteins (i.e., “viral strategy”) (37, 47). The thorough evolutionary analysis of such constrained restriction factors would benefit from novel bioinformatic methodologies specifically designed to identify adaptive evolution that operates on a background of strong purifying selection and that may further involve genetic innovations other than site-specific positive selection (e.g., indels and recombination).

A second possible explanation for the lack of strong positive selection in the Smc5/6 complex is that orthohepadnaviruses may not have been strong drivers of mammalian genome adaptation. Indeed, acute HBV infection is mostly asymptomatic, and when evolving into chronic infection the symptoms and associated morbidity appear late in life, after the reproductive age. Arguing against this interpretation are the findings of Enard and colleagues, who provided evidence that most cellular genes reported in the literature to encode HBV-interacting proteins show a strong excess of adaptation (37). This, however, remains to be functionally demonstrated because, to our knowledge, no study to date has reported evidence for a direct evolutionary arms race between an HBV protein and a cellular factor.

A third possibility is that HBx interacts with the Smc5/6 complex indirectly, through a yet-unknown intermediate cellular protein. Although we cannot formally exclude this possibility, none of our studies so far suggests that this is the case. In particular, no common cellular protein in addition to the DDB1 subunit of the E3 ligase and the six Smc5/6 subunits was recovered from HBx-expressing cells in pulldown experiments with either HBx or Smc5/6, as would be expected for an adaptor protein bridging HBx to the complex (F. Abdul and M. Strubin, unpublished data). We can further exclude any evolutionary arms race between DDB1 and HBV, because DDB1 is under strong purifying selection (data not shown) and our assays with heterologous species cells allow us to robustly exclude any species specificity between HBx and a hypothetical endogenous intermediate factor. Nevertheless, the exact HBx-Smc5/6 interface remains unknown. Evolutionary and mutagenesis analyses of HBx did not allow us to identify the viral determinants of the interaction with Smc5/6 (data not shown). The analysis of structural/docking models (see references 48 and 49 for examples) might contribute to solve this virus-host interface.

It is really remarkable that all the orthohepadnavirus HBx proteins that we tested antagonize the Smc5/6 complex and share the ability to fully substitute for human HBx in an HBV infection assay using primary human hepatocytes, especially given their low sequence identity (<38% identity for some pairs) and their long divergence time. These findings suggest that the Smc5/6 antiviral restriction activity is conserved and has been essential among mammals, and they provide additional evidence that antagonizing the Smc5/6 complex is a major function of HBx during HBV infection. Our findings further imply that in contrast to what has been documented for other restriction factors (53), Smc5/6 does not act as a species barrier to the potential zoonotic transmission of bat or primate HBVs to humans (50–52, 54).

HBVs are not restricted to mammals, as they are also found in birds, fishes, and amphibians (2, 55, 56). Because the latter viruses appear to lack an HBx gene (1, 2, 55), it would be interesting to explore if they are also restricted by Smc5/6 and, if so, what strategy these divergent hepadnaviruses use to circumvent the antiviral restriction.

Finally, because mammalian Smc6 has some evidence of adaptive evolution independently of HBV pressure, it raises the possibility that the Smc6 gene has been engaged in an evolutionary arms race with other pathogenic viruses. For example, the evolutionary adaptive changes identified in the lentiviral restriction factor MxB have been driven not by lentiviruses but likely by other pathogens (45, 57). In addition, restriction factors with a broad antiviral spectrum, such as MxA or PKR, have been evolutionarily driven by several pathogens (58, 59). It will be interesting to determine whether other DNA viruses are restricted by the Smc5/6 complex and, if so, whether they have contributed to shape the evolution of mammalian Smc5/6 complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture.

Cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Human cell lines used in the study were human embryonic kidney 293T cells and HeLa cells (gifts from Andrea Cimarelli, CIRI Lyon), as well as the human hepatoma cell line HepG2 (ATCC HB-8065). Old World monkey cells used were tantalus African green monkey (AGM) (Chlorocebus tantalus) COS-7 cells (a gift from Branka Horvat, CIRI Lyon) and vervet AGM (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) Vero cells (a gift from Andrea Cimarelli, CIRI Lyon). New World monkey cells were owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus) kidney OMK cells (CelluloNet Lyon) and cotton-headed tamarin (Saguinus oedipus) B95a cells (a gift from Branka Horvat). We also used ferret (Mustela putorius furo, from Branka Horvat) and mouse cells (NIH 3T3, a gift from Theophile Olmann's lab, CIRI Lyon). The species identity of all the cell lines used in this study was confirmed by amplification and sequencing of cytochrome b and/or beta-actin (data not shown).

Expression plasmids.

The lentivirus vectors pWPT expressing GFP, GFP-HBx, and GFP-WHx have been previously described (60–62). The X coding regions (synthesized by Genewiz) from hepadnaviruses infecting the New World wooly monkey (Lagothrix) (WMHBx) and three distant bat species, including the roundleaf bat (Hipposideros cf. ruber), the horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus Alcyone), and the tent-making bat (Uroderma bilobatum) (RBHBx, HBHBx, TBHBx, respectively) (52), were expressed from the same vector. The X insert was ligated to the pWPT-GFP backbone between the PstI and NotI sites following the T4 DNA (New England BioLabs [NEB]; M0202) ligation protocol. The plasmid was then transformed following the high-efficiency transformation protocol using NEB 10-beta Competent Escherichia coli (NEB; C3019). All the X-expressing plasmids were checked by Sanger sequencing using eGFP-F primer, 5′-CAT GGT CCT GCT GGA GTT CGT G-3′, and pWPT-R, 5′-GTC AGC AAA CAC AGT GCA CAC CA-3′. The pWPT-ΔGFP-X plasmids encoding the native form of the X proteins were obtained after digestion of the pWPT-GFP-X vectors using MluI and NotI and amplification of each X using Mlu1-pWPT-X-F primer (5′-GCT TAC GCG TTC TGC AGT CGA CGA ATT CAC CAT G-3′) and pWPT-R primer (5′-GTC AGC AAA CAC AGT GCA CAC CA-3′). Each X insert was ligated to the pWPT-ΔGFP linearized backbone following the T4 DNA (NEB-M0202) ligation protocol.

Transfection and transduction.

For recombinant-lentivirus production, plasmids were transfected in 293T cells by the calcium phosphate method. Briefly, 4.5 × 106 cells were plated in a 10-cm dish and transfected 12 h later with 15 μg of the X protein-expressing lentiviral vectors, 10 μg of packaging plasmid (psPAX2, gift from Didier Trono [Addgene plasmid 12260]), and 5 μg of envelope (pMD2G, gift from Didier Trono [Addgene plasmid 12259]). The medium was changed 6 h posttransfection. After 48 h, the viral supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C. The viral supernatants were titrated by transducing 293T or HeLa cells and measuring the GFP expression by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) 5 days later. The different mammalian cell lines were transduced by plating 0.1 × 106 to 0.5 × 106 cells in 12-well plates and adding 4 to 6 h later appropriate volumes of viral supernatants to obtain at least 65% GFP-positive cells. Because of the strong postentry block against the lentiviral vector in OMK cells due to the owl monkey TRIMcyp (63), cyclosporine was added (final concentration, 2.5 μM) to increase transduction efficiencies in these cells. Five days postransduction, cells were collected for FACS and Western blot analysis. For AGM COS-7 cells, transduction efficiencies were low and GFP-positive cells were isolated using FACS AsriaII sorting.

Luciferase reporter assay.

Transfection of plasmid DNA in HepG2 cells was performed using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche) following the manufacturer's instructions. For luciferase reporter gene assay, cells were typically seeded at a density of about 6 × 105 per 30-mm-diameter well (1 × 105 cells/cm2) and reverse transfected with 30 ng of reporter plasmid DNA pCMV-Gluc (New England BioLabs) and 2 μg of empty EBS-PL vector. The next day, cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding GFP or the diverse GFP-tagged viral X proteins. Five to 7 days later, GLuc activity was measured by adding 5 μl of the cell supernatant sample to 50 μl of room temperature assay buffer (100 mM NaCl, 35 mM EDTA, 0.1% Tween 20, 300 mM sodium ascorbate, 0.8 μM coelenterazine in 1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and immediately measuring luminescence in a luminometer (Glomax; Promega).

Western blotting.

Western blot analyses were performed as previously described (7). Cells were disrupted in 2% SDS and briefly sonicated. The protein concentration was estimated and normalized using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Novagen). The membranes were probed with 1:5,000 mouse monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (Roche; 11814460001) to detect the GFP-tagged X proteins, 1:1,000 mouse monoclonal antibodies against Smc6 (Abgent; AT3956a), 1:500 rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Smc6 (a gift from A. R. Lehmann) (NIH 3T3 [Fig. 3C]) (64), 1:1,000 rabbit polyclonal anti-Nse4 (Abgent; AP9909A), 1:10,000 mouse monoclonal anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH; Sigma-Aldrich; G8795), and 1:500 goat polyclonal anti-DDB1 (Everest Biotech) antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences; 1:5,000) were used as secondary antibodies. Detection was performed by ECL (Pierce).

Co-IP assay.

HepG2 cells were harvested and washed once with 1× PBS. The cells were resuspended in 200 μl of coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP)–lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 μM ZnCl2, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630 (nonionic nondenaturing detergent; Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitor cocktail from Sigma). The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and 20 μl was set aside as input samples. The rest of the supernatants were mixed in 800 μl of co-IP–lysis buffer with a 25-μl packed-bead volume of protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (GE Healthcare) coupled to 3 μl of anti-GFP antibody (Roche; 11814460001). After 2 h of incubation at 4°C under constant rotation, the beads were sedimented by brief centrifugation (1 min at 300 × g) and the supernatant was discarded. The beads were washed 3 times with 1 ml of co-IP–lysis buffer. Bound protein-protein complexes were released from the beads by addition of 20 μl of 2× Laemmli SDS sample buffer. The inputs and eluted proteins were resolved in a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and detected by Western blotting.

PHH isolation, HBV infection, and ELISA.

PHHs were isolated from human liver tissue from three donors as previously described (65). They were infected with PCR normalized HBV or HBVΔX at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 500 viral genome equivalents per cell (6). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Autobio Diagnostics) was used to determine the amount of HBe and HBs antigens in culture media from infected or mock-infected PHHs. The efficiency of infection was controlled by quantitative PCR analyses specific for the viral cccDNA using beta-globin levels to normalize cell numbers. DNA from infected and transduced cells was extracted using the Epicentre kit. For the cccDNA analysis, T5 exonuclease (TSE44111K; Epicentre) was added and the DNA further incubated at 37°C for 30 min and 70°C for 30 min. Specific TaqMan probes and primers were then used to assess the cccDNA content as described in reference 66. Transduction levels were estimated by the GFP expression in transduced cells by FACS analyses (BD FACSCalibur).

De novo sequencing of Smc5/6 genes.

Total RNA was extracted from 107 cells following the manufacturer's instructions (NucleoSpin RNA Blood; Macheray-Nagel; 740200). Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher; 18080) with random hexamers and oligo(dT). Single-round PCR of overlapping fragments was performed using Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB; M0491) following the manufacturer's instructions. Sequences of the Smc6 gene from owl monkey (OMK), cotton-headed monkey (B95a), tantalus and vervet AGM (COS-7 and Vero), human (293T and HepG2), and ferret cells were obtained. Primers used for the amplification and the sequencing are available in supplemental Table 1 at https://figshare.com/articles/Table_S1_Primers_used_to_amplify_and_sequence_endogenous_Smc6_from_different_mammalian_cell_lines_/6194843.

Host phylogenetic analyses.

Sequences of primate or mammalian orthologous genes were retrieved from publicly available databases using UCSC Blat and NCBI BLASTN with the human sequence as the query. After including sequences obtained from de novo sequencing in this study, the sequences of the orthologues were codon aligned using Muscle (67), with minor adjustments (alignments are in supplemental data set 1 at https://figshare.com/articles/DatasetS1_Host_gene_alignments_used_in_the_study_fasta_format_and_phylogenetic_analyses_newick_format_Nsmce1-4_Smc1-6/6194813). The names of the sequences have been made uniform: the first three letters of the host genus name followed by the first three letters of the species name (e.g., papAnu for Papio anubis or macMul for Macaca mulata). When sequences were retrieved using Blat on the primate full-genome assembly, the name of the genome assembly was used (e.g., panTro4 for Pan troglodytes or hg38 for human). The synteny of each locus of interest was analyzed in UCSC using Blat and the Genome Browser. When necessary, the genomic sequences were further retrieved and aligned to a reference gene to determine the pseudogenes and the gene orders.

We used GARD from HYPHY to perform the recombination analyses with a P value cutoff of <0.05 (28, 68). PhyML was used for the phylogenetic reconstructions with an HKY+G+I model and an approximate likelihood ratio test (aLRT) or 1,000 bootstrap replicates for branch support (69).

Positive selection analyses.

Maximum-likelihood tests to assay for positive selection were performed using three platforms: HYPHY from Kosakovsky Pond and colleagues, PAML from Yang, and Bio++ from Guéguen and colleagues (31, 32, 68). In HYPHY, we used PARRIS to detect if a subset of sites in the alignment has evolved under positive selection (30). We further used the more recent BUSTED method, which detects gene-wide evidence of positive selection within a codon alignment (29). In PAML, we used Codeml with the corresponding gene tree inferred with PhyML as input. Parameters were checked using an M0 model. The gene-coding sequence alignments were fit to models that disallow (M7) or allow (M8) positive selection. For several genes, we did not get convergence certainly because genes were too conserved and the sum of dS across the tree was too low. We therefore exclude the Codeml and Bio++ analyses of seven genes, for which the p or the q parameters of the beta distribution was extreme (<0.05 or >99 [31]) (Fig. 1C, NA). The likelihood of models was compared using a chi-square test to derive P values.

For the Smc6 gene, for which we found evidence of positive selection in some of the previously described methods, we further analyzed (i) which lineage(s) during primate evolution has been subjected to positive selection (i.e., when did the gene experience rapid evolution?) and (ii) which sites have been under positive selection (i.e., where has the gene evolved more rapidly than expected?). For branch-specific analyses, we used BS-REL from HYPHY, which identifies if certain lineages have undergone positive selection (39). To detect episodic site-specific positively selected sites, we used MEME from HYPHY (70). We also ran FUBAR in Datamonkey, which uses Bayesian inference to detect positive and negative selection at individual sites (71). In Bio++ and Codeml, we used the Bayesian posterior probability and the BEB analysis from the respective M8 model to identify codons with dN/dS ratios of >1 (sites with posterior probability of >0.90 are presented here in Fig. 2A).

Virus phylogenetics.

The nucleotide sequences of the X gene from orthohepadnaviruses were retrieved using BLASTN with the human HBx as the query. Only one sequence per orthohepadnaviral lineage was retained for this analysis. We performed the amino acid alignment with Muscle (total length, 161 aa), and we used PhyML for the phylogenetic reconstructions with a JTT+G+I model and 1,000 bootstrap replicates for branch support (69).

Ethics statement.

PHHs were prepared from adult surgical liver resections provided by Michel Rivoire's, Jean-Yves Mabrut's, and Guillaume Passot's departments. Approval from the local and national ethics committees (French Ministry of Research and Education numbers AC-2013-1871, DC-2013-1870, and DC-2008-235) and written informed consent from patients were obtained.

Accession number(s).

All the new Smc6 sequences are available at GenBank under accession numbers MF624755 to MF624761.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We very sincerely thank Léa Picard and Laurent Guéguen for the Bio++ analyses and input on evolutionary analyses, Véronique Barateau for technical support with the flow cytometry analyses, Andrea Cimarelli, Olivier Hantz, and Isabelle Chemin for scientific discussions, and Loic Peyrot, Anaelle Dubois, and Francoise Berby for technical assistance. We thank Maud Michelet, Jennifer Molle, Loic Peyrot, Anaelle Dubois, Océane Floriot, Laura Dimer, Marie-Laure Plissonnier, and Julie Lucifora (CRCL) for the isolation of primary human hepatocytes and Michel Rivoire's, Jean-Yves Mabrut's, and Guillaume Passot's staff for providing liver resections. We thank A. R. Lehmann for providing anti-Smc6 antibody. We thank Michael Emerman, Andrea Cimarelli, and Oliver Fregoso for their comments on the manuscript. We thank all the contributors of publicly available genome sequences.

This work was supported by an amfAR Mathilde Krim Phase II Fellowship (109140-58-RKHF to L.E.), a Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) Projet Innovant grant (ING20160435028 to L.E.), a FINOVI “recently settled scientist” grant (to L.E.), an ANR LabEx ECOFECT grant (ANR-11-LABX-0048 of Université de Lyon, within the program Investissements d'Avenir [ANR-11-IDEX-0007] operated by the French National Research Agency, GrASP, to L.E.), an ANRS grant (ECTZ19143 to L.E.), a fellowship from La Ligue Contre le Cancer (to L.G.), a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (310030-149626 to M.S.), and by the Canton of Geneva.

F.A., L.G., M.S., and L.E. conceptualized the study. J.H., M.S., and L.E. acquired funding. F.F., F.A., L.G., and L.E. designed the methodology. F.F. and L.E. performed the phylogenetic and evolutionary analyses. F.F., F.A., L.G., A.P., and L.E. performed experiments. All the authors analyzed the data. L.E. was the project administrator. F.A., J.H., M.S., and L.E. supervised the study. F.F. and L.E. wrote the original draft of the manuscript, and all the authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Suh A, Weber CC, Kehlmaier C, Braun EL, Green RE, Fritz U, Ray DA, Ellegren H. 2014. Early mesozoic coexistence of amniotes and hepadnaviridae. PLoS Genet 10:e1004559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dill JA, Camus AC, Leary JH, Di Giallonardo F, Holmes EC, Ng TF. 2016. Distinct viral lineages from fish and amphibians reveal the complex evolutionary history of hepadnaviruses. J Virol 90:7920–7933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00832-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauber C, Seitz S, Mattei S, Suh A, Beck J, Herstein J, Borold J, Salzburger W, Kaderali L, Briggs JAG, Bartenschlager R. 2017. Deciphering the origin and evolution of hepatitis B viruses by means of a family of non-enveloped fish viruses. Cell Host Microbe 22:387–399.e386. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feitelson MA, Bonamassa B, Arzumanyan A. 2014. The roles of hepatitis B virus-encoded X protein in virus replication and the pathogenesis of chronic liver disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets 18:293–306. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.867947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benhenda S, Cougot D, Buendia MA, Neuveut C. 2009. Hepatitis B virus X protein molecular functions and its role in virus life cycle and pathogenesis. Adv Cancer Res 103:75–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)03004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucifora J, Arzberger S, Durantel D, Belloni L, Strubin M, Levrero M, Zoulim F, Hantz O, Protzer U. 2011. Hepatitis B virus X protein is essential to initiate and maintain virus replication after infection. J Hepatol 55:996–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decorsière A, Mueller H, van Breugel PC, Abdul F, Gerossier L, Beran RK, Livingston CM, Niu C, Fletcher SP, Hantz O, Strubin M. 2016. Hepatitis B virus X protein identifies the Smc5/6 complex as a host restriction factor. Nature 531:386–389. doi: 10.1038/nature17170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy CM, Xu Y, Li F, Nio K, Reszka-Blanco N, Li X, Wu Y, Yu Y, Xiong Y, Su L. 2016. Hepatitis B virus X protein promotes degradation of SMC5/6 to enhance HBV replication. Cell Rep 16:2846–2854. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobbe N, Heck MM. 2004. The evolution of SMC proteins: phylogenetic analysis and structural implications. Mol Biol Evol 21:332–347. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhlmann F. 2016. SMC complexes: from DNA to chromosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17:399–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gligoris T, Lowe J. 2016. Structural insights into ring formation of cohesin and related smc complexes. Trends Cell Biol 26:680–693. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe Y. 2005. The importance of being Smc5/6. Nat Cell Biol 7:329–331. doi: 10.1038/ncb0405-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menolfi D, Delamarre A, Lengronne A, Pasero P, Branzei D. 2015. Essential roles of the Smc5/6 complex in replication through natural pausing sites and endogenous DNA damage tolerance. Mol Cell 60:835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kegel A, Sjogren C. 2010. The Smc5/6 complex: more than repair? Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 75:179–187. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2010.75.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Capetillo O. 2016. The (elusive) role of the SMC5/6 complex. Cell Cycle 15:775–776. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1137713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang G, Sun F, O'Brien M, Eppig JJ, Handel MA, Jordan PW. 2017. SMC5/6 is required for the formation of segregation-competent bivalent chromosomes during meiosis I in mouse oocytes. Development 144:1648–1660. doi: 10.1242/dev.145607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu C, Livingston CM, Li L, Beran RK, Daffis S, Ramakrishnan D, Burdette D, Peiser L, Salas E, Ramos H, Yu M, Cheng G, Strubin M, Delaney WE IV, Fletcher SP. 2017. The Smc5/6 complex restricts HBV when localized to ND10 without inducing an innate immune response and is counteracted by the HBV X protein shortly after infection. PLoS One 12:e0169648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duggal NK, Emerman M. 2012. Evolutionary conflicts between viruses and restriction factors shape immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 12:687–695. doi: 10.1038/nri3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson WE. 2013. Rapid adversarial co-evolution of viruses and cellular restriction factors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 371:123–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawyer SL, Wu LI, Emerman M, Malik HS. 2005. Positive selection of primate TRIM5alpha identifies a critical species-specific retroviral restriction domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2832–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409853102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daugherty MD, Malik HS. 2012. Rules of engagement: molecular insights from host-virus arms races. Annu Rev Genet 46:677–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim ES, Malik HS, Emerman M. 2010. Ancient adaptive evolution of tetherin shaped the functions of Vpu and Nef in human immunodeficiency virus and primate lentiviruses. J Virol 84:7124–7134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00468-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia B, Serra-Moreno R, Neidermyer W, Rahmberg A, Mackey J, Fofana IB, Johnson WE, Westmoreland S, Evans DT. 2009. Species-specific activity of SIV Nef and HIV-1 Vpu in overcoming restriction by tetherin/BST2. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000429. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauter D, Schindler M, Specht A, Landford WN, Munch J, Kim KA, Votteler J, Schubert U, Bibollet-Ruche F, Keele BF, Takehisa J, Ogando Y, Ochsenbauer C, Kappes JC, Ayouba A, Peeters M, Learn GH, Shaw G, Sharp PM, Bieniasz P, Hahn BH, Hatziioannou T, Kirchhoff F. 2009. Tetherin-driven adaptation of Vpu and Nef function and the evolution of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1 strains. Cell Host Microbe 6:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filleton F, Abdul F, Gerossier L, Paturel A, Hall J, Strubin M, Etienne L. 1 December 2017. Smc5/6-antagonism by HBx is an evolutionary-conserved function of hepatitis B virus infection in mammals. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/202671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.McBee RM, Rozmiarek SA, Meyerson NR, Rowley PA, Sawyer SL. 2015. The effect of species representation on the detection of positive selection in primate gene data sets. Mol Biol Evol 32:1091–1096. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perelman P, Johnson WE, Roos C, Seuanez HN, Horvath JE, Moreira MA, Kessing B, Pontius J, Roelke M, Rumpler Y, Schneider MP, Silva A, O'Brien SJ, Pecon-Slattery J. 2011. A molecular phylogeny of living primates. PLoS Genet 7:e1001342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Posada D, Gravenor MB, Woelk CH, Frost SD. 2006. Automated phylogenetic detection of recombination using a genetic algorithm. Mol Biol Evol 23:1891–1901. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murrell B, Weaver S, Smith MD, Wertheim JO, Murrell S, Aylward A, Eren K, Pollner T, Martin DP, Smith DM, Scheffler K, Kosakovsky Pond SL. 2015. Gene-wide identification of episodic selection. Mol Biol Evol 32:1365–1371. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheffler K, Martin DP, Seoighe C. 2006. Robust inference of positive selection from recombining coding sequences. Bioinformatics 22:2493–2499. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Z. 2007. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guéguen L, Gaillard S, Boussau B, Gouy M, Groussin M, Rochette NC, Bigot T, Fournier D, Pouyet F, Cahais V, Bernard A, Scornavacca C, Nabholz B, Haudry A, Dachary L, Galtier N, Belkhir K, Dutheil JY. 2013. Bio++: efficient extensible libraries and tools for computational molecular evolution. Mol Biol Evol 30:1745–1750. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gueguen L, Duret L. 6 April 2017. Unbiased estimate of synonymous and non-synonymous substitution rates with non-stationary base composition. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/124925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Demogines A, Abraham J, Choe H, Farzan M, Sawyer SL. 2013. Dual host-virus arms races shape an essential housekeeping protein. PLoS Biol 11:e1001571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng M, Ndungo E, Kaczmarek ME, Herbert AS, Binger T, Kuehne AI, Jangra RK, Hawkins JA, Gifford RJ, Biswas R, Demogines A, James RM, Yu M, Brummelkamp TR, Drosten C, Wang LF, Kuhn JH, Muller MA, Dye JM, Sawyer SL, Chandran K. 2015. Filovirus receptor NPC1 contributes to species-specific patterns of ebolavirus susceptibility in bats. Elife 4:e11785. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lou DI, Kim ET, Meyerson NR, Pancholi NJ, Mohni KN, Enard D, Petrov DA, Weller SK, Weitzman MD, Sawyer SL. 2016. An intrinsically disordered region of the DNA repair protein Nbs1 is a species-specific barrier to herpes simplex virus 1 in primates. Cell Host Microbe 20:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enard D, Cai L, Gwennap C, Petrov DA. 2016. Viruses are a dominant driver of protein adaptation in mammals. Elife 5:e12469. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Z, Wong WS, Nielsen R. 2005. Bayes empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol 22:1107–1118. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Murrell B, Fourment M, Frost SD, Delport W, Scheffler K. 2011. A random effects branch-site model for detecting episodic diversifying selection. Mol Biol Evol 28:3033–3043. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etienne L. 2015. Virus-host evolution and positive selection, p 1–13. In (ed), Encyclopedia of AIDS. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-9610-6_373-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kluge SF, Sauter D, Kirchhoff F. 2015. SnapShot: antiviral restriction factors. Cell 163:774–774.e771. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malim MH, Bieniasz PD. 2012. HIV restriction factors and mechanisms of evasion. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:a006940. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usami Y, Wu Y, Gottlinger HG. 2015. SERINC3 and SERINC5 restrict HIV-1 infectivity and are counteracted by Nef. Nature 526:218–223. doi: 10.1038/nature15400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosa A, Chande A, Ziglio S, De Sanctis V, Bertorelli R, Goh SL, McCauley SM, Nowosielska A, Antonarakis SE, Luban J, Santoni FA, Pizzato M. 2015. HIV-1 Nef promotes infection by excluding SERINC5 from virion incorporation. Nature 526:212–217. doi: 10.1038/nature15399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murrell B, Vollbrecht T, Guatelli J, Wertheim JO. 2016. The evolutionary histories of antiretroviral proteins SERINC3 and SERINC5 do not support an evolutionary arms race in primates. J Virol 90:8085–8089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00972-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heigele A, Kmiec D, Regensburger K, Langer S, Peiffer L, Sturzel CM, Sauter D, Peeters M, Pizzato M, Learn GH, Hahn BH, Kirchhoff F. 2016. The potency of Nef-mediated SERINC5 antagonism correlates with the prevalence of primate lentiviruses in the wild. Cell Host Microbe 20:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jäger S, Cimermancic P, Gulbahce N, Johnson JR, McGovern KE, Clarke SC, Shales M, Mercenne G, Pache L, Li K, Hernandez H, Jang GM, Roth SL, Akiva E, Marlett J, Stephens M, D'Orso I, Fernandes J, Fahey M, Mahon C, O'Donoghue AJ, Todorovic A, Morris JH, Maltby DA, Alber T, Cagney G, Bushman FD, Young JA, Chanda SK, Sundquist WI, Kortemme T, Hernandez RD, Craik CS, Burlingame A, Sali A, Frankel AD, Krogan NJ. 2011. Global landscape of HIV-human protein complexes. Nature 481:365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richards C, Albin JS, Demir O, Shaban NM, Luengas EM, Land AM, Anderson BD, Holten JR, Anderson JS, Harki DA, Amaro RE, Harris RS. 2015. The binding interface between human APOBEC3F and HIV-1 Vif elucidated by genetic and computational approaches. Cell Rep 13:1781–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Letko M, Booiman T, Kootstra N, Simon V, Ooms M. 2015. Identification of the HIV-1 Vif and human APOBEC3G protein interface. Cell Rep 13:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lempp FA, Wiedtke E, Qu B, Roques P, Chemin I, Vondran FWR, Le Grand R, Grimm D, Urban S. 2017. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is the limiting host factor of hepatitis B virus infection in macaque and pig hepatocytes. Hepatology 66:703–716. doi: 10.1002/hep.29112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chouteau P, Le Seyec J, Cannie I, Nassal M, Guguen-Guillouzo C, Gripon P. 2001. A short N-proximal region in the large envelope protein harbors a determinant that contributes to the species specificity of human hepatitis B virus. J Virol 75:11565–11572. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11565-11572.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drexler JF, Geipel A, Konig A, Corman VM, van Riel D, Leijten LM, Bremer CM, Rasche A, Cottontail VM, Maganga GD, Schlegel M, Muller MA, Adam A, Klose SM, Carneiro AJ, Stocker A, Franke CR, Gloza-Rausch F, Geyer J, Annan A, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Oppong S, Binger T, Vallo P, Tschapka M, Ulrich RG, Gerlich WH, Leroy E, Kuiken T, Glebe D, Drosten C. 2013. Bats carry pathogenic hepadnaviruses antigenically related to hepatitis B virus and capable of infecting human hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:16151–16156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308049110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawyer SL, Elde NC. 2012. A cross-species view on viruses. Curr Opin Virol 2:561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan H, Zhong G, Xu G, He W, Jing Z, Gao Z, Huang Y, Qi Y, Peng B, Wang H, Fu L, Song M, Chen P, Gao W, Ren B, Sun Y, Cai T, Feng X, Sui J, Li W. 2012. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife 1:e00049. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hahn CM, Iwanowicz LR, Cornman RS, Conway CM, Winton JR, Blazer VS. 2015. Characterization of a novel hepadnavirus in the white sucker (Catostomus commersonii) from the Great Lakes region of the United States. J Virol 89:11801–11811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01278-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geoghegan JL, Duchene S, Holmes EC. 2017. Comparative analysis estimates the relative frequencies of co-divergence and cross-species transmission within viral families. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006215. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitchell PS, Young JM, Emerman M, Malik HS. 2015. Evolutionary analyses suggest a function of MxB immunity proteins beyond lentivirus restriction. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005304. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitchell PS, Emerman M, Malik HS. 2013. An evolutionary perspective on the broad antiviral specificity of MxA. Curr Opin Microbiol 16:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elde NC, Child SJ, Geballe AP, Malik HS. 2009. Protein kinase R reveals an evolutionary model for defeating viral mimicry. Nature 457:485–489. doi: 10.1038/nature07529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Breugel PC, Robert EI, Mueller H, Decorsiere A, Zoulim F, Hantz O, Strubin M. 2012. Hepatitis B virus X protein stimulates gene expression selectively from extrachromosomal DNA templates. Hepatology 56:2116–2124. doi: 10.1002/hep.25928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin-Marq N, Bontron S, Leupin O, Strubin M. 2001. Hepatitis B virus X protein interferes with cell viability through interaction with the p127-kDa UV-damaged DNA-binding protein. Virology 287:266–274. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leupin O, Bontron S, Schaeffer C, Strubin M. 2005. Hepatitis B virus X protein stimulates viral genome replication via a DDB1-dependent pathway distinct from that leading to cell death. J Virol 79:4238–4245. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4238-4245.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sayah DM, Sokolskaja E, Berthoux L, Luban J. 2004. Cyclophilin A retrotransposition into TRIM5 explains owl monkey resistance to HIV-1. Nature 430:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature02777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor EM, Moghraby JS, Lees JH, Smit B, Moens PB, Lehmann AR. 2001. Characterization of a novel human SMC heterodimer homologous to the Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rad18/Spr18 complex. Mol Biol Cell 12:1583–1594. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gripon P, Diot C, Guguen-Guillouzo C. 1993. Reproducible high level infection of cultured adult human hepatocytes by hepatitis B virus: effect of polyethylene glycol on adsorption and penetration. Virology 192:534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Allweiss L, Volz T, Giersch K, Kah J, Raffa G, Petersen J, Lohse AW, Beninati C, Pollicino T, Urban S, Lutgehetmann M, Dandri M. 2018. Proliferation of primary human hepatocytes and prevention of hepatitis B virus reinfection efficiently deplete nuclear cccDNA in vivo. Gut 67:542–552. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pond SL, Frost SD, Muse SV. 2005. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21:676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murrell B, Wertheim JO, Moola S, Weighill T, Scheffler K, Kosakovsky Pond SL. 2012. Detecting individual sites subject to episodic diversifying selection. PLoS Genet 8:e1002764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murrell B, Moola S, Mabona A, Weighill T, Sheward D, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Scheffler K. 2013. FUBAR: a fast, unconstrained bayesian approximation for inferring selection. Mol Biol Evol 30:1196–1205. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li T, Robert EI, van Breugel PC, Strubin M, Zheng N. 2010. A promiscuous alpha-helical motif anchors viral hijackers and substrate receptors to the CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17:105–111. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]