Abstract

Background

Surgical‐site infection (SSI) is a potentially serious complication following colorectal surgery. The present systematic review and meta‐analysis aimed to investigate the effect of preoperative oral antibiotics and mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) on SSI rates.

Methods

A systematic review of PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was performed using appropriate keywords. Included were RCTs and observational studies reporting rates of SSI following elective colorectal surgery, in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with intravenous (i.v.) antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, compared with patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. A meta‐analysis was undertaken.

Results

Twenty‐two studies (57 207 patients) were included, of which 14 were RCTs and eight observational studies. Preoperative oral antibiotics, in combination with i.v. antibiotics and MBP, were associated with significantly lower rates of SSI than combined i.v. antibiotics and MBP in RCTs (odds ratio (OR) 0·45, 95 per cent c.i. 0·34 to 0·59; P < 0·001) and cohort studies (OR 0·47, 0·44 to 0·50; P < 0·001). There was a similarly significant effect on SSI with use of a combination of preoperative oral aminoglycoside and erythromycin (OR 0·40, 0·25 to 0·64; P < 0·001), or preoperative oral aminoglycoside and metronidazole (OR 0·51, 0·39 to 0·68; P < 0·001). Preoperative oral antibiotics were significantly associated with reduced postoperative rates of anastomotic leak, ileus, reoperation, readmission and mortality in the cohort studies.

Conclusion

Oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with MBP and i.v. antibiotics, is superior to MBP and i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis alone in reducing SSI in elective colorectal surgery.

Introduction

Surgical‐site infection (SSI) is a challenging problem following colorectal surgery. SSI can be separated into superficial and deep components, and is reported routinely until 30 days after surgery. SSI represents not only a costly expense to health services, but more importantly influences patient recovery and survival1.

Various strategies have been adopted in attempts to reduce postoperative SSI rates. Mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) alone has been shown in large data sets to have no influence on SSI2. The value of i.v. antibiotics in the immediate preoperative period is clearly established and they are currently used worldwide, with or without MBP3. Advocates of preoperative antibiotics believe that cleansing of intestinal flora influences rates of subsequent infection. Controversy remains regarding the use of short‐course oral antibiotics in the preoperative setting; although use of oral antibiotics in combination with MBP is a strategy employed widely in North America4, it remains much less common across Europe. The reasons for avoidance of MBP in Europe are multifactorial, but the trend towards enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols that exclude routine MBP is probably a significant contributor5. Concerns regarding hospital‐acquired infections including Clostridium difficile are relevant only when patients are exposed to extended bowel‐cleansing protocols6. The aim of this review was to assess only trials that included 1 day of preoperative antibiotics, and all trials assessing longer periods of preoperative antibiotic exposure were excluded.

Although the evidence for and against MBP can be debated, guidelines clearly state that there is no strong evidence for its use alone7. Evidence exists that suggests that its use in addition to oral antibiotics as part of a bowel‐cleansing protocol is beneficial with respect to SSI4. The impact of the use of oral antibiotics in the absence of MBP with regard to SSI has not been established. Antibiotics are thought to have little influence in this context because of the faecal content present.

The value of employing different regimens of oral antibiotics has also not been clearly established. Most trials have used the combination of an aminoglycoside (neomycin or kanamycin) with a macrolide such as erythromycin or with metronidazole.

The aim of the present study was to examine the impact of oral antibiotics and MBP given on the day before operation, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis at induction of anaesthesia, on rates of SSI following elective colorectal surgery. Secondary outcome measures included anastomotic leak, reoperation, duration of hospital stay, readmission and mortality. RCTs and observational studies that have assessed the role of preoperative oral antibiotics in the reduction of SSI in colorectal surgery were considered for inclusion, with the aim of determining the value of employing this preoperative strategy and to assess the best antibiotic combination available.

Methods

The systematic review and meta‐analysis was performed and reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement8.

Outcomes of interest

The primary outcome was the impact of preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis given the day before surgery, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, compared with that in patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP, on rates of SSI following elective colorectal surgery. Secondary outcomes included: the impact of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis on organ space SSI, anastomotic leak, postoperative ileus, unplanned return to the operating theatre, readmission and mortality. Postoperative SSI, anastomotic leak, ileus, return to theatre, readmission and mortality were recorded as categorized by the authors of the included studies.

Literature search and study selection

A systematic literature review was undertaken of PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to March 2017 inclusive. Combinations of the following search terms were used; [title/abstract]: (colorectal OR colon OR rectal OR colonic OR rectum) AND (surgery OR operation) AND (antibiotic OR antimicrobial). Abstracts were screened for relevance. Animal or preclinical studies, studies not published in English and review articles were excluded. Included were RCTs and observational studies reporting rates of SSI following elective colorectal surgery in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, compared with those in patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. Studies reporting prolonged preoperative oral antibiotic regimens, without the use of MBP in both groups, without i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis in both groups, and including patients undergoing emergency surgery, were excluded. Relevant full‐text articles were then appraised. Reference lists of included studies were hand‐searched for further relevant studies. Two authors performed study selection and data extraction, and any uncertainties were resolved by consensus discussion with the senior author.

Data extraction and meta‐analysis

Data were extracted and analysis performed using Review Manager version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95 per cent confidence intervals were calculated from the total number of patients and the number of events within each group. Meta‐analysis of the impact of preoperative oral antibiotics on SSI, anastomotic leak, reoperation, readmission and mortality rates was carried out using the Mantel–Haenzsel method. Meta‐analysis of the impact of preoperative oral antibiotics on postoperative length of hospital stay was done by calculating the mean difference and 95 per cent confidence interval using the inverse‐variance method. Where data other than means and standard deviations were reported, an attempt was made to calculate these values using published confidence intervals or P values, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 9, or by Wan and colleagues10. A fixed‐effects model was used unless there was significant evidence of heterogeneity when quantified using the I 2 statistic, in which case a random‐effects model was used. The significance of the overall effect was determined using the Z test. P ≤ 0·050 was considered statistically significant.

Assessment of bias

Assessment of the risk of bias was carried out using the Cochrane Collaboration tool provided by Review Manager version 5.3. Data were assessed for heterogeneity using the I 2 statistic, with guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 9. A prespecified sensitivity analysis was undertaken by estimating the treatment effect size only in double‐blind RCTs, and comparing this with the overall results. Assessment of potential publication bias was carried out by visual inspection of funnel plots.

Results

Study selection

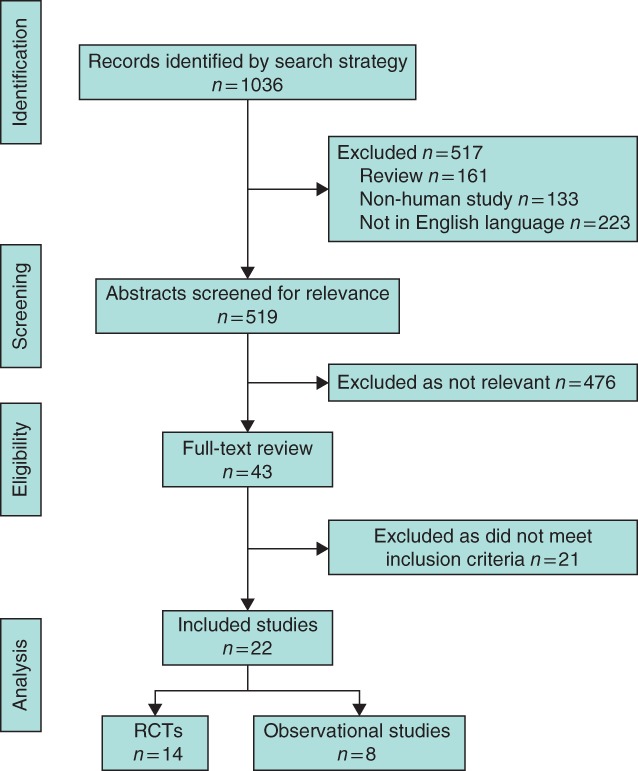

The study selection process is summarized in Fig. 1. Some 1036 abstracts were identified. At screening, 517 were excluded, of which 133 were animal or preclinical studies, 223 were not in the English language, 161 were review articles and 476 were not relevant to the review. After assessment of full‐text articles of the remaining 43 studies, 18 studies were excluded owing to the lack of MBP, prolonged courses of preoperative oral antibiotics, or the inclusion of patients undergoing emergency or urgent surgery. A further three studies were excluded as they were duplicate publications using cohorts already included in the meta‐analysis11, 12, 13. The remaining 22 studies were included in the review, of which 14 were RCTs14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and eight were observational cohorts2 4, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 (Table 1; Table S1, supporting information). These studies included a total of 57 207 patients.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing selection of articles for review

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Reference | Type of study | Placebo | Oral antibiotic combination | Intravenous antibiotic | MBP | SSI criteria | Secondary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barber et al. 14 | RCT | Yes | Neomycin + erythromycin | Clindamycin + gentamicin | Magnesium citrate | Custom | – |

| Hanel et al. 15 | RCT | No | 1 g neomycin × 6 + 200 mg metronidazole × 16 | Clindamycin + cefazolin | Clear fluids for 4 days | Custom | – |

| Kaiser et al. 16 | RCT | Yes | 1 g neomycin + 1 g erythromycin × 3 | 2 g cefoxitin or 1 g cefazolin × 1 | Magnesium citrate | Custom | – |

| Lau et al. 17 | RCT | No | 1 g neomycin + 1 g erythromycin × 3 | 500 mg metronidazole + 2 mg/kg gentamicin × 3 | Bisacodyl + magnesium citrate | Lungqvist criteria | Organ space SSI, leak, LOS |

| Khubchandani et al. 18 | RCT | No | 1 g neomycin + 1 g erythromycin × 3 | 1 g cefazolin + 1 g metronidazole × 3 | Castor oil | Custom | Leak |

| Reynolds et al. 19 | RCT | No | Neomycin + metronidazole | n.r. | n.r. | Custom | – |

| Stellato et al. 20 | RCT | No | 1 g neomycin + 1 g erythromycin × 1 | 2 g cefoxitin × 1 | Magnesium citrate + sodium phosphate | Custom | – |

| Ishida et al. 21 | RCT | No | 500 mg kanamycin + 400 mg erythromycin × 8 | 1 g cefotiam × 6 | PEG | CDC | Organ space SSI, leak |

| Lewis22 | RCT | Yes | 2 g neomycin + 2 g metronidazole × 2 | 1 g amikacin + 1 g metronidazole × 1 | Sodium phosphate | CDC | Organ space SSI, leak |

| Espin‐Basany et al. 23 | RCT | No | 1 g neomycin + 1 g metronidazole × 3 | 1 g cefoxitin × 3 | Sodium phosphate | CDC | Organ space SSI, ileus |

| Kobayashi et al. 24 | RCT | No | 1 g kanamycin + 400 mg erythromycin × 3 | 1 g cefmetazole × 1 | PEG | CDC | – |

| Oshima et al. 25 | RCT | No | 500 mg kanamycin + 500 mg metronidazole × 3 | 1 g flomoxef | Magnesium citrate | NNIS | Organ space SSI |

| Sadahiro et al. 26 | RCT | No | 500 mg kanamycin + 500 mg metronidazole × 3 | 1 g flomoxef × 1 | Sodium bicosulphate + PEG | Custom | Organ space SSI, leak |

| Hata et al. 27 | RCT | No | 1 g kanamycin + 750 mg metronidazole × 2 | 1 g cefmetazole × 1 | Sodium picosulphate + magnesium citrate | CDC | Organ space SSI, leak, ileus |

| Konishi et al. 28 | Cohort | n.a. | Kanamycin + metronidazole | Second‐generation cephalosporin | NNIS | – | |

| Cannon et al. 29 | Cohort | n.a. | n.r. | n.r. | PEG, sodium phosphate or magnesium citrate | VASQIP | – |

| Hendren et al. 30 | Cohort | n.a. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | ACS NSQIP | – |

| Morris et al. 31 | Cohort | n.a. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | Custom | Organ space SSI, leak, ileus, reoperation, LOS, readmission, mortality |

| Scarborough et al. 4 | Cohort | n.a. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | ACS NSQIP | Leak, LOS, readmission, mortality |

| Moghadamyeghaneh et al. 32 | Cohort | n.a. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | ICD‐9 | Organ space SSI, leak, reoperation, LOS, mortality |

| Kiran et al. 33 | Cohort | n.a. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | ACS NSQIP | Organ space SSI, leak, ileus, readmission, reoperation, mortality |

| Koller et al. 2 | Cohort | n.a. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | ACS NSQIP | Organ space SSI, leak, ileus, reoperation, LOS, readmission, mortality |

MBP, mechanical bowel preparation; SSI, surgical‐site infection; LOS, length of hospital stay; n.r., not recorded; PEG, polyethylene glycol; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NNIS, National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance system; n.a., not applicable; VASQIP, Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program; ACS NSQIP, American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Validity assessment

The risk of study bias is summarized in Fig. S1 (supporting information). Of the included RCTs, five14 16, 18 20, 22 were double‐blinded, three15 17, 23 were single‐blinded, and the remainder were unblinded. Most of the included cohort studies were at low risk of bias.

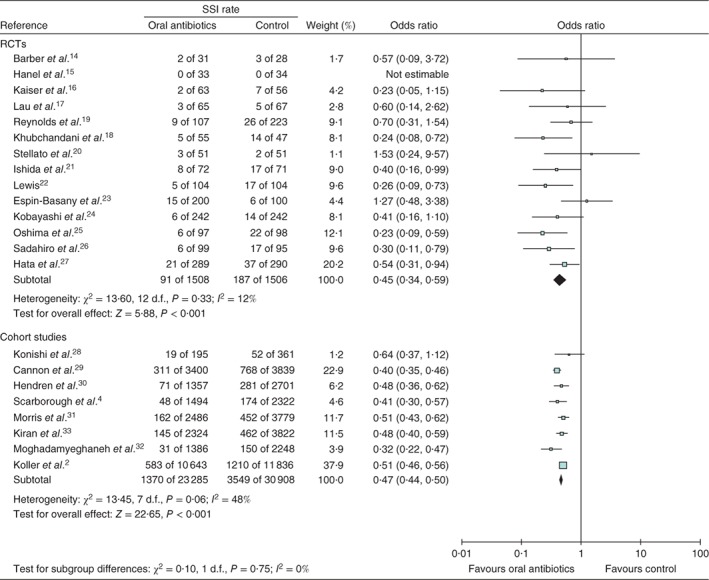

Rates of all SSIs following colorectal surgery

In the 14 RCTs14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, involving 3014 patients, rates of SSI in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, were compared with those in patients who received only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP (Fig. 2). There was minimal heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 12 per cent, P = 0·33) and therefore a fixed‐effect model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were significantly associated with lower rates of SSI (OR 0·45, 95 per cent c.i. 0·34 to 0·59; P < 0·001).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of studies that used preoperative oral antibiotics the day before colorectal surgery to prevent surgical‐site infection (SSI). A Mantel–Haenszel fixed‐effect model was used for meta‐analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Eight cohort studies2 4, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, including 54 193 patients, compared rates of SSI in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, with those in patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP (Fig. 2). There was moderate heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 48 per cent, P = 0·06) and therefore a fixed‐effect model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were significantly associated with lower rates of SSI (OR 0·47, 0·44 to 0·50; P < 0·001).

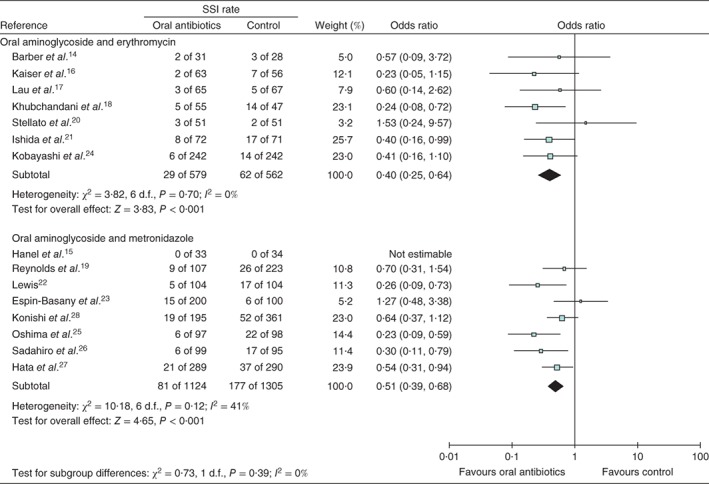

Impact of oral antibiotic combination on overall SSI rates

Seven RCTs14 16, 17, 18 20, 21 24, involving 1141 patients, examined rates of SSI in patients given a preoperative oral combination of an oral aminoglycoside (kanamycin or neomycin) and erythromycin, along with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, in comparison with patients who received only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP (Fig. 3). There was no heterogeneity between the studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·70) so a fixed‐effects model was used. The combination of preoperative oral aminoglycoside and erythromycin was associated with significantly lower rates of SSI (OR 0·40, 95 per cent c.i. 0·25 to 0·64; P < 0·001).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of studies that used preoperative oral aminoglycoside and either erythromycin or metronidazole the day before colorectal surgery to prevent surgical‐site infection (SSI). A Mantel–Haenszel fixed‐effect model was used for meta‐analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Seven RCTs15 19, 22 23, 25, 26, 27 and one cohort study28, involving 2429 patients, examined rates of SSI in patients who received a preoperative oral combination of an oral aminoglycoside (kanamycin or neomycin) and metronidazole, along with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, in comparison with patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP (Fig. 3). There was moderate heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 41 per cent, P = 0·12) and therefore a fixed‐effects model was used. The combination of preoperative oral aminoglycoside and metronidazole was associated with significantly lower rates of SSI (OR 0·51, 0·39 to 0·68; P < 0·001).

Preoperative oral antibiotics and organ space SSI

Seven RCTs17 21, 22, 23 25, 26, 27, involving 1656 patients, examined rates of organ space SSI in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, compared with those in patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was minimal heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 1·00), so a fixed‐effects model was used. There was no significant association between preoperative oral antibiotics and rates of organ space SSI (OR 0·76, 95 per cent c.i. 0·44 to 1·31; P = 0·32).

Four cohort studies2 31, 32, 33, including 38 524 patients, compared rates of organ space SSI in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, with those in patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP. There was minimal heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·99) so a fixed‐effects model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were associated with significantly lower rates of organ space SSI (OR 0·58, 0·52 to 0·66; P < 0·001).

Preoperative oral antibiotics and anastomotic leak

Six RCTs17 18, 21 22, 26 27, involving 1417 patients, examined rates of anastomotic leak in patients undergoing colorectal surgery who were given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, and in those who received only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was minimal heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·50); therefore, a fixed‐effects model was used. There was no significant association between preoperative oral antibiotics and anastomotic leak (OR 0·62, 95 per cent c.i. 0·30 to 1·28; P = 0·19).

Five cohort studies2 4, 31, 32, 33 involving 42 329 patients, examined rates of anastomotic leak in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, compared with those in patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was minimal heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·75), so a fixed‐effects model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were associated with significantly lower rates of anastomotic leak (OR 0·59, 0·53 to 0·67; P < 0·001).

Preoperative oral antibiotics and paralytic ileus

Two RCTs23 27, with 779 patients, examined rates of postoperative ileus in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, and in those given only intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was significant heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 53 per cent, P = 0·15), so a random‐effects model was used. There was no significant association between preoperative oral antibiotics and rates of paralytic ileus (OR 0·61, 95 per cent c.i. 0·11 to 3·38; P = 0·57).

In three cohort studies2 31, 33, involving 34 872 patients, rates of postoperative ileus in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, were compared with those in patients who received only intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was minimal heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·63); therefore, a fixed‐effects model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were associated with a significantly lower rate of paralytic ileus (OR 0·78, 0·72 to 0·83; P < 0·001).

Preoperative oral antibiotics and unplanned reoperation

Four cohort studies2 31, 32, 33, including 38 524 patients, examined rates of unplanned reoperation in patients undergoing colorectal surgery who received preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, compared with rates among patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was no heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·89), so a fixed‐effects model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were associated with significantly lower rates of unplanned reoperation (OR 0·72, 95 per cent c.i. 0·65 to 0·80; P < 0·001).

Preoperative oral antibiotics and length of hospital stay following colorectal surgery

A single RCT17 with 132 patients compared postoperative length of hospital stay in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, with that in patients who received only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was no significant association between preoperative oral antibiotics and length of stay: mean difference 0·3 (95 per cent c.i. –1·6 to 2·2) days (P = 0·76).

Three cohort studies2 4, 31, involving 32 662 patients, compared postoperative length of stay in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, with that among patients given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was significant heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 97 per cent, P < 0·001); therefore, a random‐effects model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were associated with a significantly shorter hospital stay: mean difference –0·6 (–1·0 to –0·3) days (P = 0·001). In addition, one cohort study32 reported that a significantly lower proportion of patients receiving combination oral antibiotics and MBP had a hospital stay of more than 30 days compared with patients who received MBP alone.

Preoperative oral antibiotics and readmission rates

Four cohort studies2 4, 31 33, involving 38 808 patients, examined rates of unplanned readmission in patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, and among those who received only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was no heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·78), so a fixed‐effects model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were associated with significantly lower rates of unplanned readmission (OR 0·87, 95 per cent c.i. 0·81 to 0·93; P < 0·001).

Preoperative oral antibiotics and mortality following colorectal surgery

Five cohort studies2 4, 31, 32, 33, involving 42 341 patients, compared postoperative mortality rates between patients given preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis and MBP, and those given only i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis with MBP. There was no heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·78), so a fixed‐effects model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were associated with significantly lower postoperative mortality rates (OR 0·65, 95 per cent c.i. 0·50 to 0·83; P < 0·001).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was undertaken, with only RCTs that employed double‐blinding used in the meta‐analysis14 16, 18 20, 22. There was minimal heterogeneity between studies (I 2 = 0 per cent, P = 0·44), and therefore a fixed‐effect model was used. Preoperative oral antibiotics were significantly associated with lower rates of SSI, with an odds ratio similar to that of the earlier analysis of all included RCTs (OR 0·33, 95 per cent c.i. 0·18 to 0·59; P < 0·001).

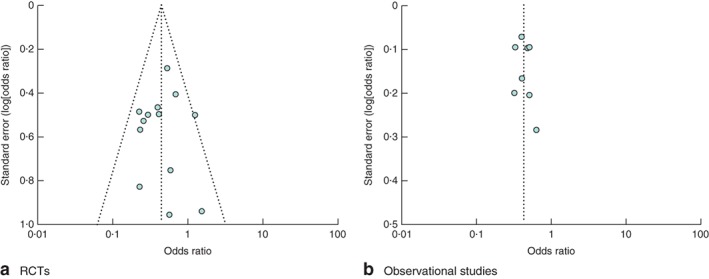

Assessment of publication bias

Visual assessment of funnel plots of the included RCTs and cohort studies with regard to reporting of all SSIs suggested no evidence of publication bias (Fig. 4). No data point was generated for Hanel and colleagues15 as no events occurred in either arm.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of a all RCTs and b all cohort studies investigating use of oral antibiotics the day before colorectal surgery to prevent surgical‐site infection

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta‐analysis suggest that preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with mechanical bowel preparation and i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis, was associated with a significant reduction in rates of SSI in elective colorectal surgery. In addition, preoperative oral antibiotics were associated with lower rates of organ space SSI, anastomotic leak, paralytic ileus, unplanned reoperation, unplanned readmission and postoperative mortality when cohort studies were considered.

These findings are in keeping with a previous meta‐analysis34 investigating the impact of preoperative oral antibiotics on SSI in colorectal surgery, although it included patients who had received preoperative oral antibiotics for prolonged periods, patients who did not receive i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis, and those who did not receive MBP in combination with oral antibiotics. Koullouros and colleagues34 also reported only on rates of postoperative SSI, whereas the present meta‐analysis considered other outcomes of clinical significance whenever they were available, including anastomotic leak, unplanned reoperation and postoperative mortality.

At present, in the USA and Canada, around 40 per cent of patients are given oral antibiotics in combination with MBP6. The combination of oral neomycin and erythromycin has been recommended for use as preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis for colorectal surgery in an advisory statement from the Medicare National Surgical Infection Prevention Project35. Outside North America, this figure is much lower. Many centres in the UK and Europe have largely moved away from the routine use of MBP in elective colorectal surgery as ERAS and fast‐track perioperative care protocols have become the standard of care. There are limited data on the value of using preoperative oral antibiotics in the unprepared colon, with one cohort study4 finding no benefit, and a further two studies2 29 reporting a reduction in SSI rates.

Based on the findings of the present meta‐analysis, it appears that, as long as one drug in the preoperative combination is an aminoglycoside (kanamycin or neomycin), then combination with either metronidazole or erythromycin has equivalent efficacy in reducing SSI. There are some pharmacological considerations that suggest metronidazole should be the favoured agent in combination with an aminoglycoside in preoperative antibiotic protocols. Erythromycin is a cytochrome P450 inhibitor and the likelihood of drug interactions is greater. Furthermore, erythromycin may also prolong the QT interval and caution is advised regarding its routine use in patients with pre‐existing cardiac disease.

The treatment effect size with regard to the reported postoperative outcomes was generally large. It is perhaps surprising that a single day of preoperative oral antibiotics has such a significant and wide‐ranging impact. Other related factors may be relevant, including methodological issues, such as variations in systems used to define and record SSI in RCTs, diagnostic coding used to analyse large observational studies, as well as many clinical factors such as case mix, complexity, operative techniques, co‐morbidities and compliance with preoperative preparation instructions. This effect size was, however, in keeping with the review of Koullouros and colleagues34, which had less stringent entry criteria. An important limitation in the present analysis was variation in the exact type of MBP used, particularly in the cohort studies, which often did not report the exact nature or timing of bowel preparation. In addition, there were variations in the definition of SSI and other complications.

Oral antibiotic prophylaxis, in combination with MBP and i.v. antibiotics, was superior to MBP and i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis alone in reducing SSI after elective colorectal resections. This treatment approach was also associated with significantly lower rates of anastomotic leak, ileus, reoperation, length of stay, readmission and mortality. There was no association between the combination of antibiotics and outcome, as long as an aminoglycoside was included. Aminoglycosides administered orally reach very low levels in the circulation35, and toxicity is vanishingly rare. It is suggested that future ERAS protocols should factor in a combination of MBP and short‐course oral antibiotic prophylaxis with an aminoglycoside and metronidazole, and i.v. antibiotic prophylaxis at induction of anaesthesia.

Supporting information

Table S1 Characteristics of included studies

Fig. S1 Risk‐of‐bias summary chart

Acknowledgements

This study was not preregistered in an independent institutional database.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Garner BH, Anderson DJ. Surgical site infections: an update. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2016; 30: 909–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koller SE, Bauer KW, Egleston BL, Smith R, Philp MM, Ross HM et al Comparative effectiveness and risks of bowel preparation before elective colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2018; 267: 734–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nelson RL, Gladman E, Barbateskovic M. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (5)CD001181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scarborough JE, Mantyh CR, Sun Z, Migaly J. Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation reduces incisional surgical site infection and anastomotic leak rates after elective colorectal resection: an analysis of colectomy‐targeted ACS NSQIP. Ann Surg 2015; 262: 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Branch‐Elliman W, Ripollone JE, O'Brien WJ, Itani KMF, Schweizer ML, Perencevich E et al Risk of surgical site infection, acute kidney injury, and Clostridium difficile infection following antibiotic prophylaxis with vancomycin plus a beta‐lactam versus either drug alone: a national propensity‐score‐adjusted retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2017; 14: e1002340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland . Guidelines for the Management of Colorectal Cancer (2017) https://www.acpgbi.org.uk/resources/guidelines-management-cancer-colon-rectum-anus-2017 [accessed 21 November 2017].

- 8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org [accessed 17 March 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Toneva GD, Deierhoi RJ, Morris M, Richman J, Cannon JA, Altom LK et al Oral antibiotic bowel preparation reduces length of stay and readmissions after colorectal surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 216: 756–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deierhoi RJ, Dawes LG, Vick C, Itani KM, Hawn MT. Choice of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis for colorectal surgery does matter. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 217: 763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Englesbe MJ, Brooks L, Kubus J, Luchtefeld M, Lynch J, Senagore A et al A statewide assessment of surgical site infection following colectomy: the role of oral antibiotics. Ann Surg 2010; 252: 514–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barber MS, Hirschberg BC, Rice CL, Atkins CC. Parenteral antibiotics in elective colon surgery? A prospective, controlled clinical study. Surgery 1979; 86: 23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hanel KC, King DW, McAllister ET, Reiss‐Levy E. Single‐dose parenteral antibiotics as prophylaxis against wound infections in colonic operations. Dis Colon Rectum 1980; 23: 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaiser AB, Herrington JL Jr, Jacobs JK, Mulherin JL Jr, Roach AC, Sawyers JL. Cefoxitin versus erythromycin, neomycin, and cefazolin in colorectal operations. Importance of the duration of the surgical procedure. Ann Surg 1983; 198: 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lau WY, Chu KW, Poon GP, Ho KK. Prophylactic antibiotics in elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 1988; 75: 782–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khubchandani IT, Karamchandani MC, Sheets JA, Stasik JJ, Rosen L, Riether RD. Metronidazole vs. erythromycin, neomycin, and cefazolin in prophylaxis for colonic surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 1989; 32: 17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reynolds JR, Jones JA, Evans DF, Hardcastle JD. Do preoperative oral antibiotics influence sepsis rates following elective colorectal surgery in patients receiving perioperative intravenous prophylaxis? Surg Res Commun 1989; 7: 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stellato TA, Danziger LH, Gordon N, Hau T, Hull CC, Zollinger RM Jr et al Antibiotics in elective colon surgery. A randomized trial of oral, systemic, and oral/systemic antibiotics for prophylaxis. Am Surg 1990; 56: 251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ishida H, Yokoyama M, Nakada H, Inokuma S, Hashimoto D. Impact of oral antimicrobial prophylaxis on surgical site infection and methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection after elective colorectal surgery. Results of a prospective randomized trial. Surg Today 2001; 31: 979–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewis RT. Oral versus systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in elective colon surgery: a randomized study and meta‐analysis send a message from the 1990s. Can J Surg 2002; 45: 173–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Espin‐Basany E, Sanchez‐Garcia JL, Lopez‐Cano M, Lozoya‐Trujillo R, Medarde‐Ferrer M, Armadans‐Gil L et al Prospective, randomised study on antibiotic prophylaxis in colorectal surgery. Is it really necessary to use oral antibiotics? Int J Colorectal Dis 2005; 20: 542–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kobayashi M, Mohri Y, Tonouchi H, Miki C, Nakai K, Kusunoki M; Mie Surgical Infection Research Group . Randomized clinical trial comparing intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis alone with oral and intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of a surgical site infection in colorectal cancer surgery. Surg Today 2007; 37: 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oshima T, Takesue Y, Ikeuchi H, Matsuoka H, Nakajima K, Uchino M et al Preoperative oral antibiotics and intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis reduce the incidence of surgical site infections in patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing IPAA. Dis Colon Rectum 2013; 56: 1149–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sadahiro S, Suzuki T, Tanaka A, Okada K, Kamata H, Ozaki T et al Comparison between oral antibiotics and probiotics as bowel preparation for elective colon cancer surgery to prevent infection: prospective randomized trial. Surgery 2014; 155: 493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hata H, Yamaguchi T, Hasegawa S, Nomura A, Hida K, Nishitai R et al Oral and parenteral versus parenteral antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery (JMTO PREV 07‐01): a phase 3, multicenter, open‐label, randomized trial. Ann Surg 2016; 263: 1085–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, Nagawa H. Elective colon and rectal surgery differ in risk factors for wound infection: results of prospective surveillance. Ann Surg 2006; 244: 758–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cannon JA, Altom LK, Deierhoi RJ, Morris M, Richman JS, Vick CC et al Preoperative oral antibiotics reduce surgical site infection following elective colorectal resections. Dis Colon Rectum 2012; 55: 1160–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hendren SH, Fritze D, Banerjee M, Kubus J, Cleary RK, Englesbe MJ et al Antibiotic choice is independently associated with risk of surgical site infection after colectomy: a population based cohort study. Ann Surg 2013; 257: 469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morris MS, Graham LA, Chu DI, Cannon JA, Hawn MT. Oral antibiotic bowel preparation significantly reduces surgical site infection rates and readmission rates in elective colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2015; 261: 1034–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Hanna MH, Carmichael JC, Mills SD, Pigazzi A, Nguyen NT et al Nationwide analysis of outcomes of bowel preparation in colon surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 220: 912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kiran RP, Murray AC, Chiuzan C, Estrada D, Forde K. Combined preoperative mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics significantly reduces surgical site infection, anastomotic leak, and ileus after colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2015; 262: 416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koullouros M, Khan N, Aly EH. The role of oral antibiotics prophylaxis in prevention of surgical site infection in colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017; 32: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. DiPiro JT, Patrias JM, Townsend RJ, Bowden TA Jr, Hooks VH III, Smith RB et al Oral neomycin sulfate and erythromycin base before colon surgery: a comparison of serum and tissue concentrations. Pharmacotherapy 1985; 5: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Characteristics of included studies

Fig. S1 Risk‐of‐bias summary chart