Abstract

Background

Despite growing evidence to support use of preoperative mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) plus oral antibiotic bowel preparation (OABP) compared with MBP alone or no bowel preparation before colorectal surgery, evidence supporting use of MBP plus OABP relative to OABP alone is lacking. This study aimed to investigate whether the addition of MBP to OABP was associated with improved clinical outcomes after colorectal surgery compared with outcomes following OABP alone.

Methods

Patients who underwent colorectal surgery and preoperative bowel preparation with either OABP alone or MBP plus OABP were identified using the American College of Surgeons' National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Colectomy Targeted Participant Use Data File for 2012–2015. Thirty‐day postoperative outcomes were compared, estimating the average treatment effect with propensity score matching and inverse probability‐weighted regression adjustment.

Results

In the final study population of 20 594 patients, 90·2 per cent received MBP plus OABP and 9·8 per cent received OABP alone. Patients who received MBP plus OABP had a lower incidence of superficial surgical‐site infection (SSI), organ space SSI, any SSI, postoperative ileus, sepsis, unplanned reoperation and mortality, and a shorter length of hospital stay (all P < 0·050). After propensity score matching and inverse probability‐weighted regression adjusted analysis, MBP plus OABP was associated with a reduction in superficial SSI, any SSI, postoperative ileus and unplanned reoperation (all P < 0·050).

Conclusions

Use of MBP plus OABP before colectomy was associated with reduced SSI, postoperative ileus, sepsis and unplanned reoperations, and shorter length of hospital stay compared with OABP alone.

Introduction

In 1973, Nichols and colleagues1 demonstrated that the addition of preoperative oral antibiotic bowel preparation (OABP) to mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) was associated with a lower risk of wound infection after colorectal surgery. Since then, evidence for different methods of preoperative bowel preparation on postoperative outcomes, especially surgical‐site infections (SSIs), anastomotic leak, postoperative ileus, sepsis, readmission, reoperation, mortality and length of hospital stay (LOS), has been equivocal2 3. Existing reports have evaluated use of MBP and OABP, alone or in combination, relative to no bowel preparation, with limited data comparing the utility of each component of bowel preparation4, 5, 6, 7. A 2011 Cochrane review2 comparing MBP with no bowel preparation found no significant difference in the primary outcome of anastomotic leak, and no significant difference in the secondary outcomes of mortality, peritonitis, reoperation, wound infection and infectious extra‐abdominal complications. Recent RCTs8, 9, 10 have similarly demonstrated that MBP alone does not improve postoperative outcomes. In contrast, recent studies4 11, 12, 13, including RCTs and meta‐analyses, have demonstrated a clear reduction in SSI with MBP plus OABP compared with no bowel preparation. MBP plus OABP has also been independently associated with reduced rates of anastomotic leak and postoperative ileus compared with MBP alone and with no bowel preparation5 14, 15. The reduction in SSI associated with MBP plus OABP was also associated with a reduction in wound dehiscence, pneumonia, prolonged ventilation, sepsis, septic shock, LOS, unplanned reoperations and readmissions6 7, 16.

Although there is strong evidence to support the use of MBP plus OABP compared with MBP alone, evidence supporting use of the combined bowel preparation relative to OABP alone is lacking. Existing RCTs have not investigated this question, and observational studies have not answered it adequately owing to small sample sizes13 14, 16. With the 2015 release of the American College of Surgeons' National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS‐NSQIP), there is now a sufficient sample size to measure the effect of MBP plus OABP on postoperative outcomes relative to OABP alone. This study aimed to use these data to investigate whether the addition of MBP provided clinical benefit beyond the use of OABP alone.

Methods

Data sources and patient population

This study was performed using data from the ACS‐NSQIP Colectomy Targeted Participant Use Data File (PUF) for 2012–2015. In addition to variables included within the generalized ACS‐NSQIP, the 2015 Colectomy PUF contains information on 22 procedure‐specific variables collected from 239 participating sites17. Additional procedure‐specific information can be obtained by merging the two ACS‐NSQIP databases using unique case identifiers. All data are collected by trained clinical reviewers and audited to maximize inter‐reviewer reliability. As the ACS‐NSQIP databases comprise a limited data set, patient consent was waived and the study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

Patients undergoing colorectal resection were identified using relevant Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes (44140, 44141, 44143, 44144, 44145, 44146, 44147, 44150, 44151, 44160, 44204, 44205, 44206, 44207, 44208 and 44210) (Table S1, supporting information). CPT codes were used to determine operative approach (laparoscopic versus open), type of resection (ileocolic resection, partial colectomy, total colectomy or Hartmann procedure/low anterior resection) and stoma formation. Patients undergoing abdominoperineal resection or panproctocolectomy were excluded. Patients with missing information regarding preoperative bowel preparation, those who did not receive preoperative bowel preparation and those who received only MBP were excluded. Patients undergoing non‐elective or emergency surgery were also excluded, as were those with missing data required in the final multivariable model. Patients were stratified into two groups based on the preoperative bowel preparation received: OABP alone, and MBP plus OABP.

Baseline patient characteristics included patient age, sex, race and BMI. BMI was categorized according to WHO guidelines18 as either underweight (less than 18·5 kg/m2), normal (18·5–25 kg/m2), overweight/obese (more than 25 to less than 35 kg/m2) or ‘morbidly obese’ (35 kg/m2 or above). Preoperative physical status was classified according to the ASA physical status score19. Co‐morbidities were determined using relevant ACS‐NSQIP variables, including history of weight loss, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension requiring medication, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ascites, and chronic use of steroids or immunosuppressants.

Study outcomes

Outcomes of interest included 30‐day postoperative superficial SSI, deep SSI, organ space SSI, wound dehiscence, anastomotic leak, postoperative ileus, pneumonia, prolonged ventilator use (for more than 48 h), urinary tract infection, sepsis, septic shock, and venous thromboembolism (VTE) using definitions specified in the ACS‐NSQIP operations manual. Other outcomes included LOS for the index admission, unplanned reoperation or readmission within 30 days of surgery and 30‐day postoperative mortality.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were reported as mean(s.d.) or median (i.q.r.) values and compared with Student's t test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test respectively. Categorical data were reported as whole numbers and proportions and compared using Pearson's χ2 test. Univariable and multivariable logistical regression analyses were performed to assess the relationship between binary study outcomes and bowel preparation type. Specifically, patient and operative characteristics with a corresponding P value of less than 0·200 in univariable analysis were included in the multivariable models. Variables that demonstrated a P value below 0·100 in multivariable analysis were retained for each outcome (Table S2, supporting information). Results from regressions were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95 per cent confidence intervals. LOS was analysed using a negative binomial regression model and reported as an incidence rate ratio (IRR) with corresponding 95 per cent c.i.

To account for potential residual confounding and differences in patient and operative characteristics between the treatment groups, propensity score‐matched (PSM) analysis was performed. The propensity score was generated using logistic regression that specified type of bowel preparation as the dependent variable and adjusted for variables that showed a statistically significant association with the treatment groups in univariable analysis. All patients in the OABP group were matched with at least one patient in the MBP plus OABP group with a caliper of less than 0·10.

To account further for bias and imbalance in co‐variables, an inverse probability‐weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA) was performed, in which weights are inversely proportional to the probability of treatment and multivariable regression analysis of the outcome is performed simultaneously. Regression analysis was used for binary outcomes; Poisson regression was used for LOS as negative binomial regression was not available in the statistical software implementation of IPWRA. Co‐variables adjusted for in these analyses were the same as those described for above models and analyses. Both PSM and IPWRA analyses produce an average treatment effect (ATE) representing the average difference between the estimated risk of complications if all patients received MBP plus OABP and the estimated risk of complications if all patients received OABP alone. Standardized differences and variance ratios were used to assess balance of co‐variables over bowel preparation method.

All analyses were performed using Stata® 14.2 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). A P value of < 0·05 was considered to represent statistical significance.

Results

Patient, disease and operative characteristics

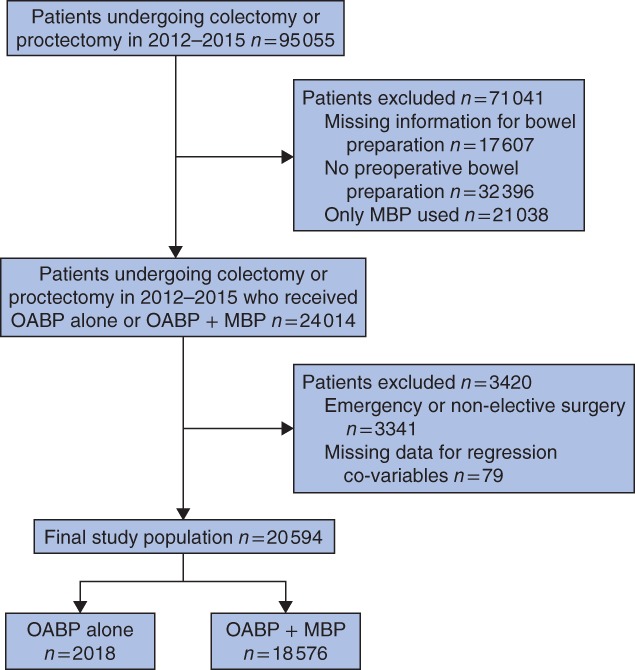

The ACS‐NSQIP Colectomy PUF contained information on 95 055 surgical patients (Fig. 1). Of these, 17 607 had missing information about bowel preparation, 32 396 did not receive preoperative bowel preparation, and 21 038 received only MBP. After excluding 3341 patients who had an emergency or non‐elective procedure and 79 with missing data for a co‐variable of interest, the final study population comprised 20 594 patients, among whom 18 576 (90·2 per cent) received MBP plus OABP and 2018 (9·8 per cent) received OABP alone.

Figure 1.

Derivation of the study population using the American College of Surgeons' National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Colectomy Targeted Participant User File. MBP, mechanical bowel preparation; OABP, oral antibiotic bowel preparation

Patients who received OABP alone were younger than those who received MBP plus OABP (median (i.q.r.) age 60 (49–70) versus 61 (51–70) years respectively; P < 0·001 (Table 1)) and were proportionally more likely to belong to a minority ethnic group (26·5 versus 21·5 per cent respectively; P < 0·001). A greater proportion of patients who received OABP alone had more than 10 per cent weight loss in the 6 months before surgery (4·9 per cent versus 3·6 per cent in patients who received MBP plus OABP; P = 0·004). Patients who received OABP alone were more likely to use steroids and/or immunosuppressants for chronic conditions or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) compared with those who had MBP plus OABP (12·9 versus 8·3 per cent, P < 0·001; 12·4 versus 6·8 per cent P < 0·001, respectively). A greater proportion of patients who received OABP alone required more than 4 units of blood transfusion in the 72 h before surgery (1·0 per cent versus 0·3 per cent in patients who had MBP plus OABP; P < 0·001). Those who received OABP alone were more likely to have IBD as the indication for surgery (15·9 versus 7·6 per cent respectively; P < 0·001); the opposite was true for patients with colonic cancer as the indication (35·8 versus 41·8 per cent; P < 0·001). Patients who received OABP alone were more likely to undergo ileocolic resection or total colectomy than those who received MBP plus OABP (27·9 versus 20·6 per cent and 5·7 versus 4·9 per cent respectively; both P < 0·001). Finally, patients who received MBP plus OABP were less likely to undergo stoma formation (9·8 per cent versus 12·6 per cent of patients who received OABP alone; P < 0·001).

Table 1.

Comparison of patient and operative characteristics by preoperative bowel preparation

| Overall (n = 20 594) | OABP alone (n = 2018) | MBP + OABP (n = 18 576) | P ‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61 (51–70) | 60 (49–70) | 61 (51–70) | < 0·001¶ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 9934 : 10 660 | 938 : 1080 | 8996 : 9580 | 0·097 |

| Ethnicity | < 0·001 | |||

| White | 16 074 (78·1) | 1484 (73·5) | 14 590 (78·5) | |

| Black | 1705 (8·3) | 203 (10·1) | 1502 (8·1) | |

| Hispanic | 1748 (8·5) | 219 (10·9) | 1529 (8·2) | |

| Other/unknown | 1067 (5·2) | 112 (5·6) | 955 (5·1) | |

| ASA fitness grade | 0·726 | |||

| II | 10 977 (53·3) | 1091 (54·1) | 9886 (53·2) | |

| III | 9101 (44·2) | 875 (43·4) | 8226 (44·3) | |

| IV | 516 (2·5) | 52 (2·6) | 464 (2·5) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 0·001 | |||

| < 18·5 | 426 (2·1) | 55 (2·7) | 371 (2·0) | |

| 18·5 to ≤ 25 | 5747 (27·9) | 643 (31·9) | 5104 (27·5) | |

| > 25 to < 35 | 11 335 (55·0) | 1047 (51·9) | 10 288 (55·4) | |

| ≥ 35 | 3086 (15·0) | 273 (13·5) | 2813 (15·1) | |

| More than 10% weight loss in past 6 months | 766 (3·7) | 98 (4·9) | 668 (3·6) | 0·004 |

| Current smoker | 3440 (16·7) | 349 (17·3) | 3091 (16·6) | 0·454 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2804 (13·6) | 248 (12·3) | 2556 (13·8) | 0·067 |

| Hypertension | 9384 (45·6) | 885 (43·9) | 8499 (45·8) | 0·104 |

| History of CHF | 89 (0·4) | 10 (0·5) | 79 (0·4) | 0·648 |

| History of COPD | 823 (4·0) | 67 (3·3) | 756 (4·1) | 0·102 |

| Ascites | 32 (0·2) | 2 (0·1) | 30 (0·2) | 0·499 |

| On haemodialysis | 61 (0·3) | 8 (0·4) | 53 (0·3) | 0·383 |

| On steroid for chronic condition | 1801 (8·7) | 260 (12·9) | 1541 (8·3) | < 0·001 |

| On steroid/immunosuppressant for IBD | 1509 (7·3) | 250 (12·4) | 1259 (6·8) | < 0·001 |

| Received more than 4 units blood transfusion in 72 h before surgery | 86 (0·4) | 21 (1·0) | 65 (0·3) | < 0·001 |

| Indication for surgery | < 0·001 | |||

| Colonic cancer | 8496 (41·3) | 723 (35·8) | 7773 (41·8) | |

| IBD | 1735 (8·4) | 321 (15·9) | 1414 (7·6) | |

| Diverticular disease | 5236 (25·4) | 462 (22·9) | 4774 (25·7) | |

| Other | 5127 (24·9) | 512 (25·4) | 4615 (24·8) | |

| Approach | 0·720 | |||

| Open | 6819 (33·1) | 661 (32·8) | 6158 (33·2) | |

| Minimally invasive | 13 775 (66·9) | 1357 (67·2) | 12 418 (66·8) | |

| Procedure | < 0·001 | |||

| Ileocolic resection | 4392 (21·3) | 564 (28·0) | 3828 (20·6) | |

| Partial colectomy | 8176 (39·7) | 743 (36·8) | 7433 (40·0) | |

| Total colectomy | 1027 (5·0) | 115 (5·7) | 912 (4·9) | |

| Hartmann procedure/LAR | 6999 (34·0) | 596 (29·5) | 6403 (34·5) | |

| Stoma | < 0·001 | |||

| Yes | 2081 (10·1) | 254 (12·6) | 1827 (9·8) | |

| No | 18 513 (89·9) | 1764 (87·4) | 16 749 (90·2) | |

| Duration of surgery (h)† | 0·808 | |||

| < 3 | 11 391 (55·3) | 1117 (55·4) | 10 274 (55·3) | |

| 3–5 | 6984 (33·9) | 691 (34·3) | 6293 (33·9) | |

| > 5 | 2218 (10·8) | 209 (10·4) | 2009 (10·8) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (i.q.r.).

Data were missing for one patient in the oral antibiotic bowel preparation (OABP) group.

MBP, mechanical bowel preparation; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; LAR, low anterior resection.

χ2 test, except

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Postoperative complications

Some 3649 patients (17·7 per cent) developed one or more complications. The most common were postoperative ileus (10·4 per cent) and any SSI (6·3 per cent) (Table 2). The incidence of postoperative complications was lower among patients who received MBP plus OABP than in those who had OABP alone (17·4 versus 21·1 per cent respectively; P < 0·001). The incidence of superficial SSI (2·8 versus 4·2 per cent; P = 0·001) and organ space SSI (2·9 versus 4·0 per cent; P = 0·005) was lower among patients who received MBP plus OABP than in patients who received OABP alone. Similarly, patients who received MBP plus OABP were less likely to develop postoperative ileus (10·1 per cent versus 12·6 per cent in patients who had OABP alone; P = 0·001) or postoperative sepsis (2·1 versus 3·1 per cent respectively; P = 0·002), or to require reoperation within 30 days (3·4 versus 5·0 per cent; P < 0·001). Patients who received MBP plus OABP were more likely to develop VTE (1·4 versus 0·6 per cent; P = 0·005).

Table 2.

Postoperative clinical outcomes by preoperative bowel preparation

| Overall (n = 20 594) | OABP alone (n = 2018) | MBP + OABP (n = 18 576) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any postoperative complication | 3649 (17·7) | 426 (21·1) | 3223 (17·3) | < 0·001 |

| Postoperative complication | ||||

| Superficial SSI | 609 (3·0) | 84 (4·2) | 525 (2·8) | 0·001 |

| Deep SSI | 124 (0·6) | 16 (0·8) | 108 (0·6) | 0·244 |

| Open space SSI | 611 (3·0) | 80 (4·0) | 531 (2·9) | 0·005 |

| Any SSI | 1288 (6·3) | 171 (8·5) | 1117 (6·0) | < 0·001 |

| Wound dehiscence | 99 (0·5) | 10 (0·5) | 89 (0·5) | 0·919 |

| Anastomotic leak | 495 of 20 564 (2·4) | 56 of 2015 (2·8) | 439 of 18 549 (2·4) | 0·251 |

| Postoperative ileus | 2132 of 20 581 (10·4) | 254 of 2017 (12·6) | 1878 of 18 564 (10·1) | 0·001 |

| Pneumonia | 197 (1·0) | 25 (1·2) | 172 (0·9) | 0·170 |

| Prolonged ventilation | 126 (0·6) | 16 (0·8) | 110 (0·6) | 0·272 |

| UTI | 373 (1·8) | 39 (1·9) | 334 (1·8) | 0·667 |

| Sepsis | 446 (2·2) | 63 (3·1) | 383 (2·1) | 0·002 |

| Septic shock | 153 (0·7) | 20 (1·0) | 133 (0·7) | 0·172 |

| VTE | 271 (1·3) | 13 (0·6) | 258 (1·4) | 0·005 |

| Reoperation | 729 (3·5) | 100 (5·0) | 629 (3·4) | < 0·001 |

| Unplanned readmission | 1757 (8·5) | 173 (8·6) | 1584 (8·5) | 0·944 |

| Mortality | 91 (0·4) | 15 (0·7) | 76 (0·4) | 0·032 |

| LOS (days)* | 5·3(4·4) | 5·7(5·4) | 5·2(4·2) | < 0·001‡ |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean(s.d.).

OABP, oral antibiotic bowel preparation; MBP, mechanical bowel preparation; SSI, surgical‐site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism; LOS, length of hospital stay.

χ2 test, except

Student's t test.

Overall, 91 patients (0·4 per cent) died, and 1757 (8·5 per cent) were readmitted within 30 days of surgery. Although readmissions were comparable between the two groups (P = 0·944), postoperative mortality was lower among patients who received MBP plus OABP than in those receiving OABP alone (0·4 versus 0·7 per cent respectively; P = 0·032). Overall, the mean(s.d.) LOS for the index admission was 5·3(4·4) days, and was shorter in patients who had MBP plus OABP (5·2(4·2) days versus 5·7(5·4) days in those who had OABP alone; P < 0·001).

Adjusted analysis of postoperative complications

Similar differences were observed on adjusted multivariable analysis. Patients who received MBP plus OABP demonstrated 32 per cent lower odds of developing superficial SSI (OR 0·68, 95 per cent c.i. 0·54 to 0·86; P = 0·001), 24 per cent lower odds of developing organ space SSI (OR 0·76, 0·59 to 0·96; P = 0·023) and 29 per cent lower odds of developing sepsis (OR 0·71, 0·54 to 0·93; P = 0·012) (Table 3). Similarly, patients who received MBP plus OABP had 20 per cent lower odds of developing postoperative ileus (OR 0·80, 0·69 to 0·92; P = 0·002) and 34 per cent lower odds of requiring reoperation within 30 days of the index operation (OR 0·66, 0·53 to 0·82; P < 0·001). However, these patients had a greater risk of developing VTE (OR 2·18, 1·25 to 3·82; P = 0·006). Patients who received MBP plus OABP demonstrated 47 per cent lower odds of dying within 30 days of surgery (OR 0·53, 0·30 to 0·93; P = 0·027) and their LOS was 8 per cent shorter (IRR 0·92, 95 per cent c.i. 0·89 to 0·95; P < 0·001).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of perioperative outcomes following mechanical plus oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus oral antibiotic bowel preparation alone

| Adjusted odds ratio | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Any postoperative complication | 0·80 (0·71, 0·90) | < 0·001 |

| Postoperative complication | ||

| Superficial SSI | 0·68 (0·54, 0·86) | 0·001 |

| Deep SSI | 0·78 (0·45, 1·32) | 0·347 |

| Organ space SSI | 0·76 (0·59, 0·96) | 0·023 |

| Any SSI | 0·71 (0·60, 0·84) | < 0·001 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0·92 (0·47, 1·77) | 0·794 |

| Anastomotic leak | 0·87 (0·66, 1·16) | 0·342 |

| Postoperative ileus | 0·80 (0·69, 0·92) | 0·002 |

| Pneumonia | 0·72 (0·47, 1·10) | 0·128 |

| Prolonged ventilation | 0·74 (0·43, 1·26) | 0·267 |

| UTI | 0·92 (0·65, 1·28) | 0·605 |

| Sepsis | 0·71 (0·54, 0·93) | 0·012 |

| Septic shock | 0·68 (0·42, 1·10) | 0·115 |

| VTE | 2·18 (1·25, 3·82) | 0·006 |

| Reoperation | 0·66 (0·53, 0·82) | < 0·001 |

| Unplanned readmission | 1·04 (0·88, 1·23) | 0·655 |

| Mortality | 0·53 (0·30, 0·93) | 0·027 |

| LOS (IRR) | 0·92 (0·89, 0·95) | < 0·001 |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. SSI, surgical‐site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism; LOS, length of hospital stay; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Inverse probability‐weighted regression and propensity score‐matched analyses

The weights on IPWRA‐balanced co‐variables (the weighted distribution of each co‐variable) were no different between the OABP alone and the MBP plus OABP groups (P = 0·204) (Tables S2 and S3, supporting information). In IPWRA, use of MBP plus OABP was associated with a 1·2 per cent reduction in the rate of superficial SSI (ATE −0·0123, 95 per cent c.i. −0·0215 to −0·0031; P = 0·009), a 1·0 per cent reduction in organ space SSI (ATE −0·0100, −0·0189 to −0·0010; P = 0·030), a 2·2 per cent reduction in any SSI (ATE −0·0224, −0·0353 to −0·0095; P = 0·001) and a 2·3 per cent reduction in postoperative ileus compared with OABP alone (ATE −0·0226, −0·0378 to −0·0074; P = 0·004) (Table 4). MBP plus OABP was associated with a 1·5 per cent reduction in reoperation within 30 days of index surgery (ATE −0·0150, −0·0251 to −0·0050; P = 0·003) and a 0·45‐day reduction in LOS (ATE −0·4457, −0·6903 to −0·2012; P < 0·001) compared with OABP alone. Similar findings were observed in PSM analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Average treatment effects using inverse probability weight (regression adjustment) and propensity score matching

| Inverse probability weight (regression adjustment) | Propensity score matching | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATE | P | ATE | P | |

| Any postoperative complication | −0·0322(0·0095) (−0·0509, −0·0136) | 0·001 | −0·0352(0·0122) (−0·0591, −0·0113) | 0·004 |

| Postoperative complication | ||||

| Superficial SSI | −0·0123(0·0047) (−0·0215, −0·0031) | 0·009 | −0·0140(0·0057) (−0·0252, −0·0028) | 0·014 |

| Deep SSI | −0·0018(0·0021) (−0·0058, 0·0023) | 0·395 | −0·0008(0·0020) (−0·0047, 0·0030) | 0·670 |

| Organ space SSI | −0·0100(0·0046) (−0·0189, −0·0010) | 0·030 | −0·0062(0·0057) (−0·0174, 0·0049) | 0·273 |

| Any SSI | −0·0224(0·0066) (−0·0353, −0·0095) | 0·001 | −0·0208(0·0078) (−0·0361, −0·0055) | 0·008 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0·0008(0·0014) (−0·0020, 0·0036) | 0·579 | 0·0002(0·0023) (−0·0044, 0·0048) | 0·924 |

| Anastomotic leak | −0·0038(0·0039) (−0·0115, 0·0038) | 0·328 | −0·0015(0·0042) (−0·0097, 0·0068) | 0·730 |

| Postoperative ileus | −0·0226(0·0078) (−0·0378, −0·0074) | 0·004 | −0·0229(0·0092) (−0·0409, −0·0049) | 0·013 |

| Pneumonia | −0·0027(0·0026) (−0·0077, 0·0023) | 0·289 | −0·0018(0·0036) (−0·0089, 0·0054) | 0·629 |

| Prolonged ventilation | −0·0021(0·0022) (−0·0064, 0·0022) | 0·348 | −0·0021(0·0029) (−0·0078, 0·0036) | 0·471 |

| UTI | −0·0009(0·0033) (−0·0073, 0·0055) | 0·780 | −0·0013(0·0047) (−0·0105, 0·0079) | 0·781 |

| Sepsis | −0·0063(0·0037) (−0·0136, 0·0010) | 0·091 | −0·0024(0·0047) (−0·0115, 0·0068) | 0·610 |

| Septic shock | −0·0029(0·0025) (−0·0078, 0·0019) | 0·240 | −0·0024(0·0032) (−0·0087, 0·0039) | 0·451 |

| VTE | 0·0084(0·0019) (0·0046, 0·0122) | < 0·001 | 0·0080(0·0024) (0·0033, 0·0126) | 0·001 |

| Reoperation | −0·0150(0·0051) (−0·0251, −0·0050) | 0·003 | −0·0128(0·0065) (−0·0255, −0·0001) | 0·048 |

| Unplanned readmission | 0·0057(0·0065) (−0·0070, 0·0183) | 0·382 | 0·0051(0·0077) (−0·0101, 0·0202) | 0·511 |

| Mortality | −0·0031(0·0020) (−0·0070, 0·0008) | 0·116 | −0·0020(0·0021) (−0·0062, 0·0021) | 0·338 |

| LOS (IRR) | −0·4457(0·1248) (−0·6903, −0·2012) | < 0·001 | −0·3242(0·1909) (−0·6985, 0·0500) | 0·090 |

Values are mean(s.e.m.) (95 per cent c.i.). ATE, average treatment effect; SSI, surgical‐site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism; LOS, length of hospital stay; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Discussion

This study evaluated the relative benefit of MBP plus OABP compared with OABP alone. Unlike earlier analyses with small numbers6 14, 16 20, the present study included 2018 patients who received OABP alone, a number sufficient to observe that addition of MBP to OABP was associated with lower odds of developing SSI, postoperative ileus, sepsis or the need for reoperation, and a reduction in postoperative LOS.

The observed benefits of adding MBP to OABP were confirmed in multiple methods of analysis: univariable and multivariable logistic regression, PSM and IPWRA analyses. All methods demonstrated statistically significant benefits for MBP plus OABP versus OABP alone, with reduced rates of superficial SSI and any SSI. Although the magnitude of the effects was reduced on matched analysis relative to unmatched analysis, the differences were still clinically significant, especially when considering the relative rare event rates and the consequence to patients of any of the study outcomes. For example, the number needed to treat with MBP plus OABP is 45 to avoid one SSI. Results from other studies have been discordant. Although one study14 found a lower rate of SSI for MBP plus OABP versus OABP alone (3·2 versus 4·4 per cent respectively), with lower anastomotic leak (2·8 versus 5·5 per cent) and mortality (0·3 versus 1·1 per cent) rates, the differences were not statistically significantly different owing to the low number of patients (91) who received OABP alone. In a matched analysis of NSQIP data15, albeit with much smaller numbers, there was no difference in SSI, anastomotic leak, ileus or mortality when comparing MBP plus OABP with OABP alone.

The present study also showed that MBP plus OABP was associated with reduced LOS. This may have been a consequence of the reduced burden of septic complications, but the present data, along with findings from previous studies, suggest that administration of MBP in addition to OABP is safe and may potentially lead to improved postoperative outcomes following colorectal surgery.

Despite the benefits of adding MBP to OABP, it has been suggested13 16 that MBP may be associated with preoperative dehydration, electrolyte imbalances and prolonged ileus. Although the data in the present study do not permit specific reporting on preoperative dehydration or electrolyte imbalances, the addition of MBP to OABP was associated with a significant improvement in postoperative ileus (ATE −0·02) relative to OABP alone by each method of analysis, suggesting that neither dehydration nor electrolyte imbalance is a major problem. This is consistent with other reports16 demonstrating reduced odds of postoperative ileus following the addition of MBP to OABP.

The present study did, however, indicate that the odds of developing VTE were 2·2 times higher with MBP plus OABP than with OABP alone. Although the data do not suggest a mechanism for this observation, additional research is warranted to investigate potential factors associated with the observed higher incidence of VTE in this subgroup.

The present study has several limitations. It is subject to the inherent limitations of all observational studies, including selection bias and the inability to make causal inferences. To limit selection bias, propensity score matching and inverse probability‐weighted analyses were used, although some residual confounding may still be unaccounted for. It was not possible to take into account potential differences in the methods of bowel preparation, as details pertaining to the antibiotic regimens used as OABP or the method of MBP are not routinely reported in ACS‐NSQIP databases. Although ACS‐NSQIP records the type of bowel preparation prescribed to patients, it was not possible to confirm that each patient had completed the bowel preparation as prescribed or the exact timing of bowel preparation before surgery. Regarding antibiotic therapy, neither the type of antibiotic nor the duration of therapy could be ascertained. Given that ACS‐NSQIP is deidentified, it was not possible to identify individual hospitals or providers, so potential variations in bowel preparation use and methods could not be accounted for. Although ACS‐NSQIP is a clinical data set, important clinically relevant data, including the administration of perioperative prophylactic parenteral antibiotics and the development of postoperative Clostridum difficile colitis, are not collected routinely and therefore could not be included in this analysis. As ACS‐NSQIP captures clinical outcomes within 30 days of the index operation, long‐term clinical and functional outcomes cannot be reported.

Despite these limitations, MBP plus OABP was associated with reduced odds of developing SSI, postoperative ileus, sepsis or need for reoperation compared with OABP alone, with odds reductions ranging from 20 to 34 per cent, as well as reduced LOS. These effects were confirmed on matched analysis. The results support the use of MBP in addition to OABP for bowel preparation before colorectal surgery.

Supporting information

Table S1 Current procedure codes and number of patients

Table S2 Covariables with p<0·2 in univariable model and covariables in final model with p<0·1 in multivariable models by outcome

Table S3 Covariate balance summary

Acknowledgements

The American College of Surgeons' National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) and the hospitals participating in the ACS‐NSQIP are the source of the data used in this article; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding information No funding

References

- 1. Nichols RL, Broido P, Condon RE, Gorbach SL, Nyhus LM. Effect of preoperative neomycin–erythromycin intestinal preparation on the incidence of infectious complications following colon surgery. Ann Surg 1973; 178: 453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Güenaga KF, Matos D, Wille‐Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; (9)CD001544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellows CF, Mills KT, Kelly TN, Gagliardi G. Combination of oral non‐absorbable and intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics alone in the prevention of surgical site infections after colorectal surgery: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Tech Coloproctol 2011; 15: 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim EK, Sheetz KH, Bonn J, DeRoo S, Lee C, Stein I et al A statewide colectomy experience: the role of full bowel preparation in preventing surgical site infection. Ann Surg 2014; 259: 310–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiran RP, Murray AC, Chiuzan C, Estrada D, Forde K. Combined preoperative mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics significantly reduces surgical site infection, anastomotic leak, and ileus after colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2015; 262: 416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dolejs SC, Guzman MJ, Fajardo AD, Robb BW, Holcomb BK, Zarzaur BL et al Bowel preparation is associated with reduced morbidity in elderly patients undergoing elective colectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 21: 372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morris MS, Graham LA, Chu DI, Cannon JA, Hawn MT. Oral antibiotic bowel preparation significantly reduces surgical site infection rates and readmission rates in elective colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2015; 261: 1034–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bucher P, Gervaz P, Soravia C, Mermillod B, Erne M, Morel P. Randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation versus no preparation before elective left‐sided colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jung B, Påhlman L, Nyström PO, Nilsson E; Mechanical Bowel Preparation Study Group . Multicentre randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colonic resection. Br J Surg 2007; 94: 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Contant CM, Hop WC, van't Sant HP, Oostvogel HJ, Smeets HJ, Stassen LP et al Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2007; 370: 2112–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lewis RT. Oral versus systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in elective colon surgery: a randomized study and meta‐analysis send a message from the 1990s. Can J Surg 2002; 45: 173–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nelson RL, Gladman E, Barbateskovic M. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (5)CD001181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cannon JA, Altom LK, Deierhoi RJ, Morris M, Richman JS, Vick CC et al Preoperative oral antibiotics reduce surgical site infection following elective colorectal resections. Dis Colon Rectum 2012; 55: 1160–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scarborough JE, Mantyh CR, Sun Z, Migaly J. Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation reduces incisional surgical site infection and anastomotic leak rates after elective colorectal resection: an analysis of colectomy‐targeted ACS NSQIP. Ann Surg 2015; 262: 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garfinkle R, Abou‐Khalil J, Morin N, Ghitulescu G, Vasilevsky CA, Gordon P et al Is there a role for oral antibiotic preparation alone before colorectal surgery? ACS‐NSQIP analysis by coarsened exact matching. Dis Colon Rectum 2017; 60: 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Althumairi AA, Canner JK, Pawlik TM, Schneider E, Nagarajan N, Safar B et al Benefits of bowel preparation beyond surgical site infection: a retrospective study. Ann Surg 2016; 264: 1051–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American College of Surgeons . ACS NSQIP Participant Use Data File; 2017. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/acs-nsqip/program-specifics/participant-use [accessed 19 April 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 18. WHO . Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO: Geneva, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dripps RD. New classification of physical status. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 1963; 24: 111. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Hanna MH, Carmichael JC, Mills SD, Pigazzi A, Nguyen NT et al Nationwide analysis of outcomes of bowel preparation in colon surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 220: 912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Current procedure codes and number of patients

Table S2 Covariables with p<0·2 in univariable model and covariables in final model with p<0·1 in multivariable models by outcome

Table S3 Covariate balance summary