Abstract

Purpose

To determine if interstitial features at chest CT enhance the effect of emphysema on clinical disease severity in smokers without clinical pulmonary fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, an objective CT analysis tool was used to measure interstitial features (reticular changes, honeycombing, centrilobular nodules, linear scar, nodular changes, subpleural lines, and ground-glass opacities) and emphysema in 8266 participants in a study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) called COPDGene (recruited between October 2006 and January 2011). Additive differences in patients with emphysema with interstitial features and in those without interstitial features were analyzed by using t tests, multivariable linear regression, and Kaplan-Meier analysis. Multivariable linear and Cox regression were used to determine if interstitial features modified the effect of continuously measured emphysema on clinical measures of disease severity and mortality.

Results

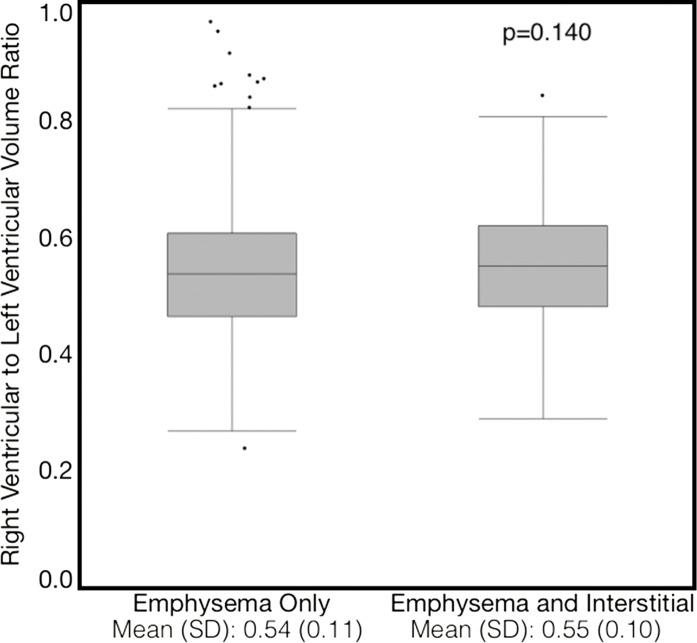

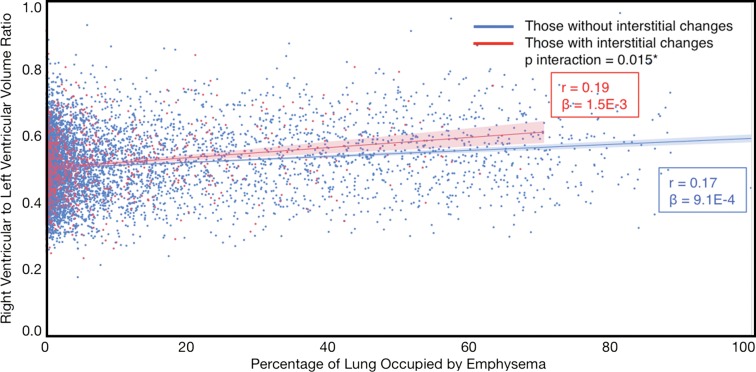

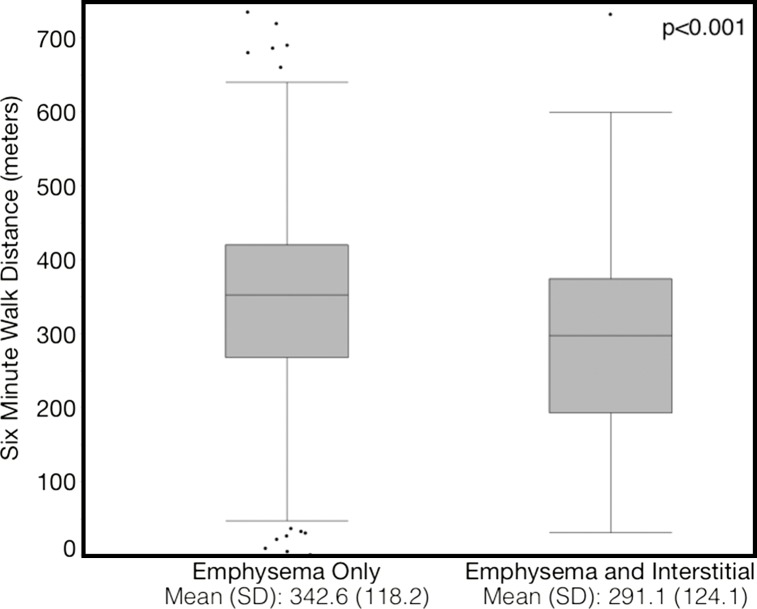

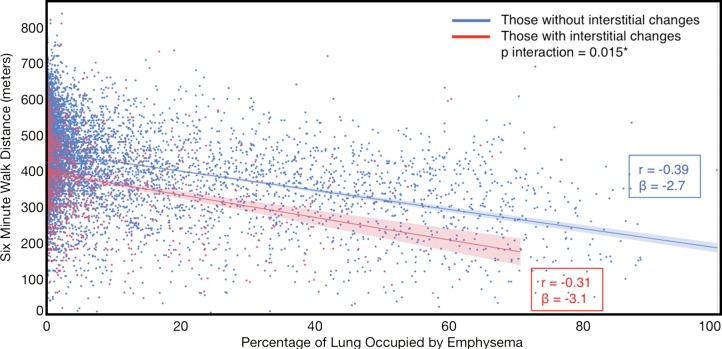

Compared with individuals with emphysema alone, those with emphysema and interstitial features had a higher percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (absolute difference, 6.4%; P < .001), a lower percentage predicted diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (absolute difference, 7.4%; P = .034), a 0.019 higher right ventricular–to–left ventricular (RVLV) volume ratio (P = .029), a 43.2-m shorter 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) (P < .001), a 5.9-point higher St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score (P < .001), and 82% higher mortality (P < .001). In addition, interstitial features modified the effect of emphysema on percentage predicted DLCO, RVLV volume ratio, 6WMD, SGRQ score, and mortality (P for interaction < .05 for all).

Conclusion

In smokers, the combined presence of interstitial features and emphysema was associated with worse clinical disease severity and higher mortality than was emphysema alone. In addition, interstitial features enhanced the deleterious effects of emphysema on clinical disease severity and mortality.

© RSNA, 2018

See also the editorial by Grenier in this issue.

Introduction

Smoking results in a wide range of parenchymal abnormalities in the lungs, including both airspace dilatation and alveolar destruction in the form of emphysema and inflammation and scarring in the form of interstitial changes and fibrosis (1,2). The presence of emphysema on chest CT scans has been repeatedly demonstrated to be associated with worse physiologic measures such as lung function and exercise capacity, as well as with higher mortality (3–5). Meanwhile, subtle visually and objectively defined interstitial features in smokers without clinical interstitial lung disease (ILD) or fibrosis have been shown to be associated with lower lung volumes, reduced exercise capacity, and higher mortality (6–11). These features typically include reticular changes, honeycombing, centrilobular nodules, linear scar, nodular changes, subpleural line, and ground-glass opacities that occur in the absence of clinical or radiologic ILD, and they are often visually described as interstitial lung abnormalities (ILAs) (7,8,11). However, whether these interstitial features modify the effect of emphysema on outcomes is unknown. We hypothesized that in smokers with emphysema, the additional presence of interstitial features would be associated with worse physiologic measures, reduced exercise capacity, worse quality of life, and higher mortality. In addition, we hypothesized that interstitial features would enhance the deleterious effect of emphysema on these outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

We performed our retrospective cohort study using clinical and radiologic data from a study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) called the COPDGene study, which has been described elsewhere (10,12–15). Briefly, 10 306 smokers aged 45–80 years with at least a 10–pack-year history and a small number of never-smoking “healthy” individuals were enrolled at 21 clinical study centers in the United States between October 2006 and January 2011 and underwent baseline testing that included an extensive interview, volumetric non—contrast material–enhanced thin-section CT of the chest, and spirometry (12). Participants were excluded from enrollment in the COPDGene study if their predominant lung condition was either bronchiectasis or ILD on the basis of a review of clinical or imaging findings, as detailed in Appendix E1 (online). Because of their lack of clear spirometric definition and their highly heterogeneous clinical and genetic characteristics, individuals with a preserved ratio and impaired spirometry (PRISm)—defined as a reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) in the setting of preserved FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio—were eligible to enroll in COPDGene, but data in these individuals were analyzed separately (12,16). As shown in Figure E1 (online), we performed the analyses in our study in a “baseline” group and in three predefined subgroups: those with follow-up (mortality) information, those with ventricular volume measurements, and those with diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) measurements. Individuals were excluded from the baseline group if they were never smokers; if they had PRISm; or if they did not have complete baseline imaging and clinical information for all of the spirometric, exercise capacity, and respiratory health–related quality of life outcomes and covariates. Follow-up of the COPDGene participants is ongoing, and for our study we excluded individuals from the mortality analyses who did not have current follow-up information. The ventricular volume measurements were obtained from prior work, and data in those individuals in whom the measurements could not be performed were excluded from our study (14). Finally, DLCO was measured at one COPDGene site (National Jewish Health, Denver, Colo) in a sample of convenience, and only individuals with DLCO measurements were included in our diffusing capacity analyses (15). The baseline COPDGene data set used for our study was generated on August 31, 2016. The mortality COPDGene data set used for our study was generated on December 18, 2016, with back censoring as described in Appendix E1 (online). The COPDGene study was approved by the institutional review boards at all the centers, and our study was approved as an ancillary study by the COPDGene Ancillary Study Committee and the Partners Institutional Review Board (Boston, Mass). All of the participants in the COPDGene Study provided written informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization. Additional details regarding our study design and the COPDGene study design are available in Appendix E1 (online).

CT Analyses

Two forms of objective CT analysis were performed in our study: classification of the lung parenchyma and measurement of the right ventricular and left ventricular volume. These methods have been described previously and are described in detail in Appendix E1 (online) (4,6,14).

A detailed description of the parenchymal analysis tool used for this study is available in Appendix E1. Briefly, our approach used the local tissue density histogram characteristics of a particular portion of lung tissue combined with that region’s distance from the pleural surface to label that area as a particular tissue subtype (4,6,13). By using this method, each portion of the lung parenchyma was labeled as a particular radiologic tissue type. These parenchymal tissue types included normal parenchyma; emphysema, which was defined as centrilobular emphysema, paraseptal emphysema, and panlobular emphysema; and interstitial features, which were defined as reticular changes, honeycombing, centrilobular nodules, linear scar, nodular changes, subpleural line, and ground-glass opacities (Fig E2 [online]). The aggregate volume of these radiologic tissue type volumes were summed to the total CT lung volume for each patient, and the radiologic tissue type volumes were expressed as a percentage of total lung volume (ie, percentage normal, percentage emphysema, and percentage interstitial features).

The right ventricular–to–left ventricular (RVLV) volume ratio measurement technique involved the use of a statistical model of the heart’s surface developed from anatomic segmentations obtained from individuals with a range of cardiac diseases and disorders (14). From these surface-fitting models, measures of cardiac morphology, including estimates of both the epicardial (wall and chamber) and endocardial (chamber) volume of each ventricle, can be extracted. For the analyses, the epicardial volumes were used to calculate the RVLV volume ratio (ratio of right ventricular epicardial volume to left ventricular epicardial volume) (14).

Definition of Disease

The percentage of lung occupied by emphysematous and interstitial features was measured and analyzed both continuously and as present versus absent (dichotomized). For the dichotomized analyses, there are limited guidelines for what thresholds to use to define the presence or absence of emphysema and interstitial changes using objective CT analysis. Several studies (17,18) have used other techniques to determine normal ranges of emphysema, but these have largely been limited to non-smoking populations or to other forms of CT (eg, cardiac). Others have suggested that 10% of the lung occupied by emphysema is a reasonable, albeit arbitrary, threshold to define the presence of disease (19–22). However, more recent work in individuals with advanced interstitial disease suggests that a threshold of 15% identifies those at a higher risk for decline in lung function (2). Because we were specifically interested in the interaction between emphysema and interstitial features, we selected this latter threshold.

With regard to interstitial features, to our knowledge, there is limited work identifying an objective threshold to define early or mild interstitial features such as visually defined ILAs. Although the visual definition of ILAs requires that they occupy more than 5% of any lung zone, previous work suggests that when using the objective approach utilized in our study, this threshold may be overly sensitive and nonspecific, resulting in a large percentage of the cohort being defined as having interstitial features (7,11,13). Because of this, we selected 10% as the threshold for our study. Of note, this threshold resulted in a prevalence of participants with interstitial features similar to that reported in prior visual analyses of smokers (7,11).

Although these cutoffs were used in the primary analyses, to evaluate the possibility that the observed associations were due to the cutpoints selected, the interaction between emphysema and interstitial features was also analyzed by using a continuous-by-continuous interaction term. Details are available in Appendix E1 (online).

Statistical Analyses

The Student t test and Fisher exact test were used to determine if there were baseline differences between individuals with and those without interstitial features.

Additive effect.—Student t testing and multivariable linear regression were used to determine if there was a difference between those with emphysema alone and those with emphysema and interstitial features with regard to the following: the percentage predicted FEV1, the percentage predicted FVC, the percentage predicted DLCO, the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) in meters, the RVLV volume ratio, and the total St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score (23). Kaplan-Meier analysis, the log-rank test, and multivariable Cox regression were used to determine if there was a difference in mortality between these two groups.

Effect modification.—Pearson correlation and univariable linear regression were used to determine the univariable associations between emphysema and continuous outcomes in individuals with and those without interstitial features. An interaction term was created to test for the interaction between continuously measured emphysema and the presence or absence of interstitial features. As mentioned above and as detailed in Appendix E1 (online), an additional interaction term was created to test for the interaction between continuously measured emphysema and continuously measured interstitial features. Multivariable linear and Cox regression were used to determine whether the presence of interstitial features modified the effect of emphysema on the continuously measured outcomes and mortality.

Multivariable linear regression analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted FEV1, except for the spirometric measures, which were not adjusted for percentage predicted FEV1. The multivariable Cox regression analyses were adjusted for the same covariates as the multivariable linear models as well as for CT-measured total coronary calcium score calculated by using previously described methods (24,25). All of the variables were assessed by using the Schoenfeld residuals method, and all satisfied the proportional hazards assumption with the exception of current smoking status; therefore, the adjusted Cox models were stratified according to current smoking status (26).

The reported P values are two sided, P < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance, and all analyses were performed by using SAS, version 9.4, or JMP, version 12 (Cary, NC).

Results

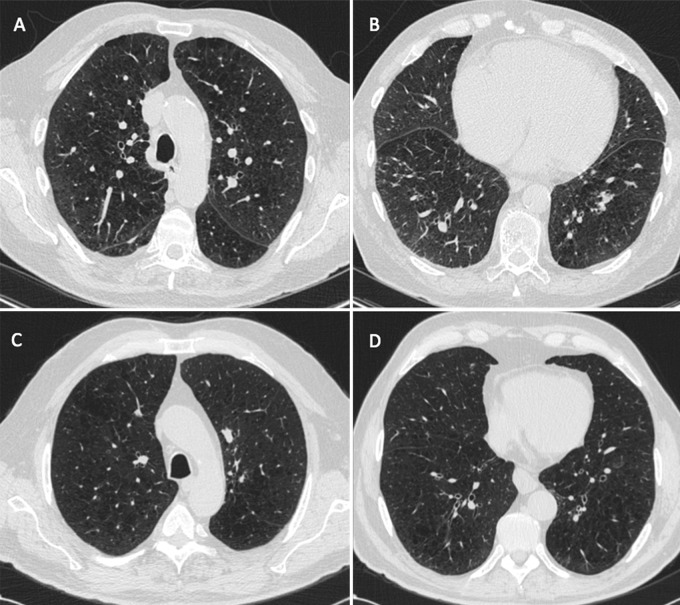

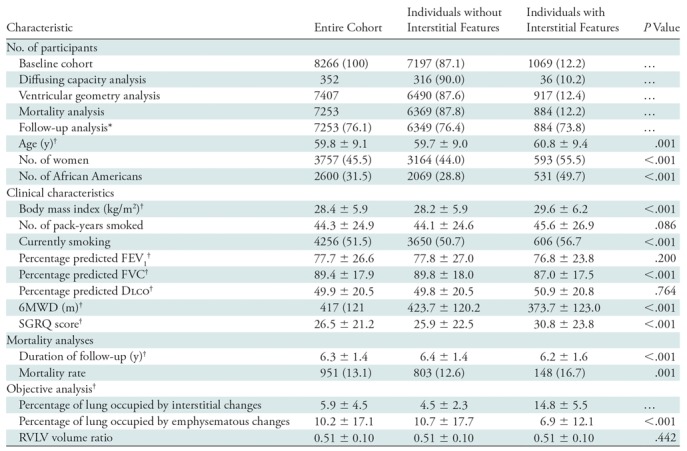

As shown in Table 1 the cohort was largely white, with a mean age of 59.8 years, and it had a slight male predominance (4509 [54.5%] of 8266). A total of 8266 participants had baseline clinical and imaging data available, including spirometric data. Of these participants, 352 had percentage predicted DLCO measurements available, 7407 had ventricular geometry measurements available, and 7253 had mortality data available (mean duration of follow-up, 6.3 years ± 1.5 [standard deviation]) (Table 1 and Fig E1 [online]). Those with interstitial features were older, were more likely to be female, were more likely to be African-American, had a higher body mass index, lower lung function, a shorter 6MWD, and a higher SGRQ score. Representative CT images in individuals with and those without interstitial features who had similar amounts of emphysema are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1:

Baseline Clinical and Imaging Characteristics

Note.—Unless otherwise specified, data are numbers of patients, with percentages in parentheses. Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding. P values for comparison between individuals with and those without interstitial features were based on the t test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for categoric variables. DLCO = diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide, FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FVC = forced vital capacity, SGRQ = St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, 6MWD = 6-minute walk distance, RVLV = right ventricular to left ventricular.

*Data in parentheses are mean lengths of follow-up in months.

†Data are means ± standard deviations.

Figure 1:

A–D, Representative axial CT images in individuals with and those without interstitial features but with similar percentages of lung occupied by emphysema show the effects of the presence of interstitial features. A, B, Images in a 74-year-old man with interstitial features (percentage interstitial = 14.3%). The percentage of his lung occupied by emphysema was 20.7%. His St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score was 48. His 6-minute walk distance was 225 m. His right ventricular–to–left ventricular volume ratio was 0.75. He died during follow-up. C, D, Images in a 73-year-old man without interstitial features (percentage interstitial = 6.1%). The percentage of his lung occupied by emphysema was 20.5%. His SGRQ score was 53. His 6-minute walk distance was 480 m. His right ventricular–to–left ventricular volume ratio was 0.61. He did not die during follow-up.

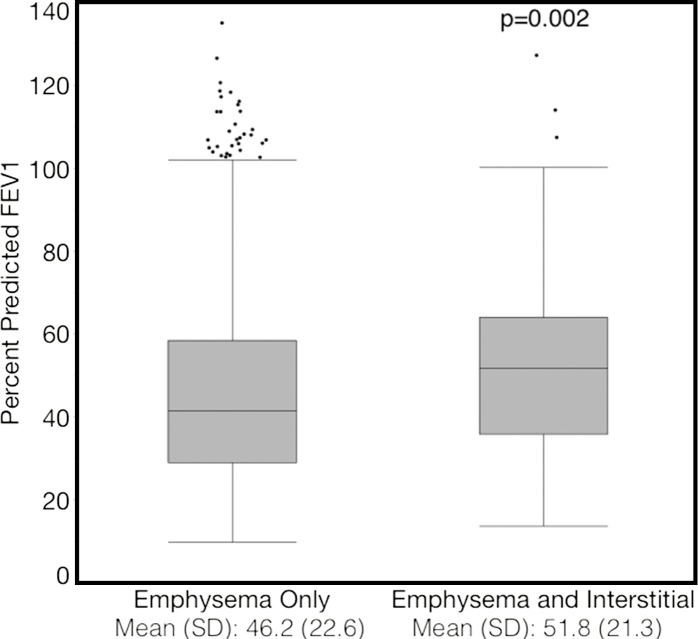

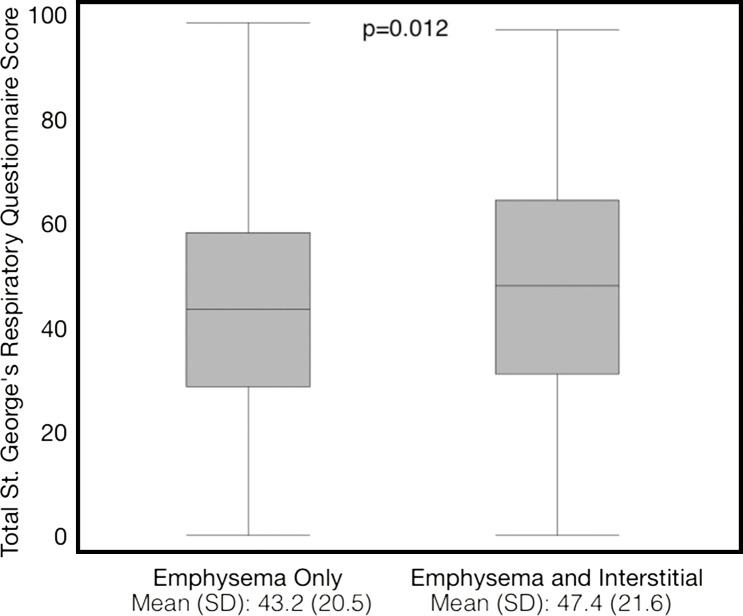

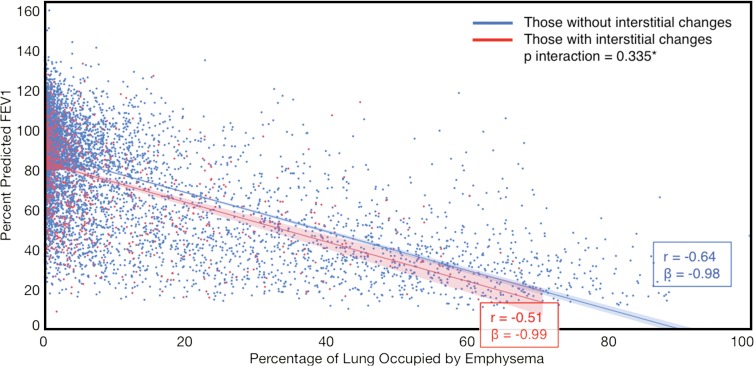

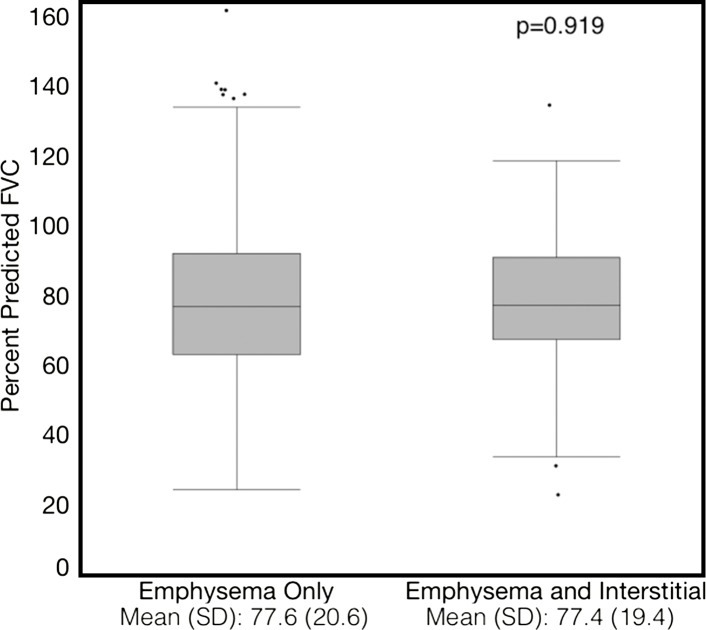

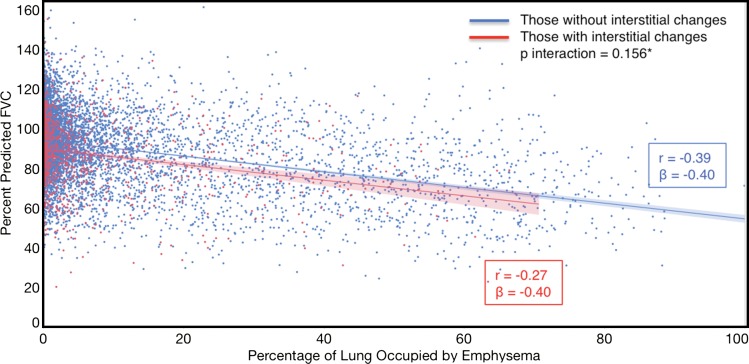

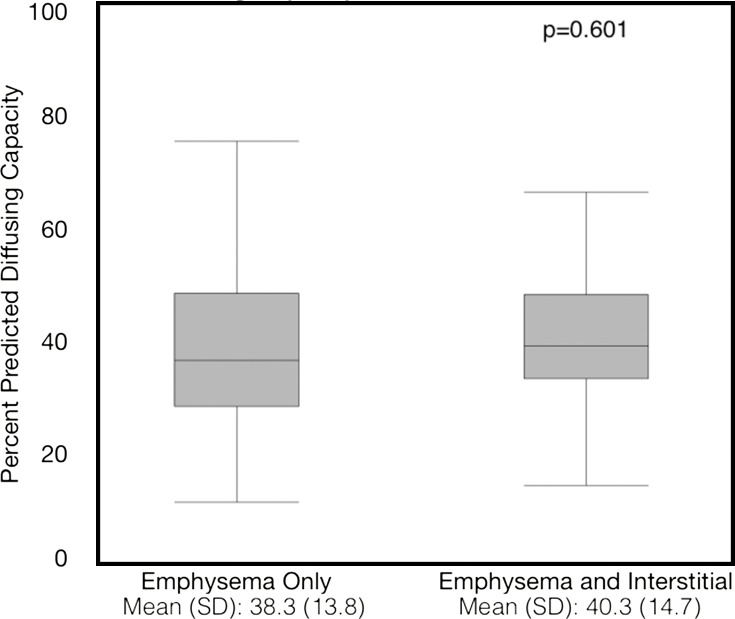

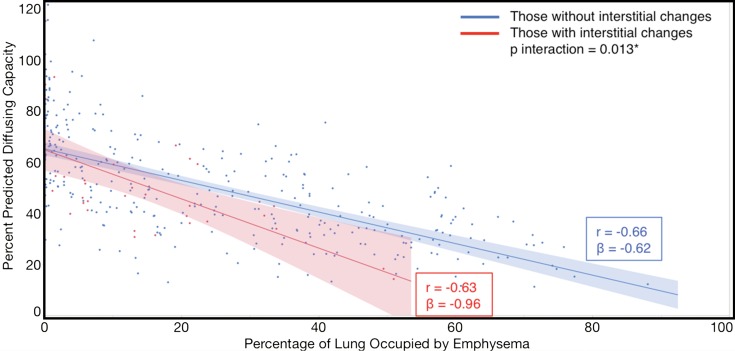

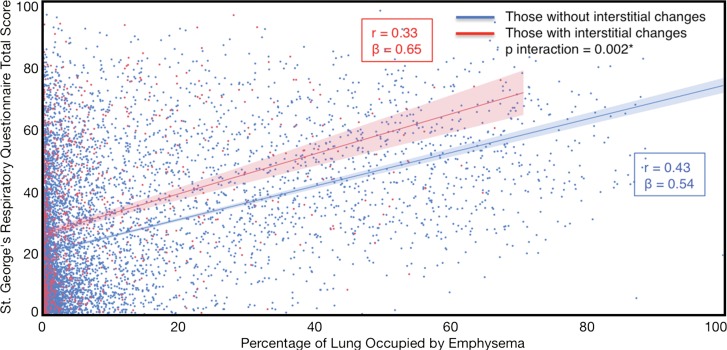

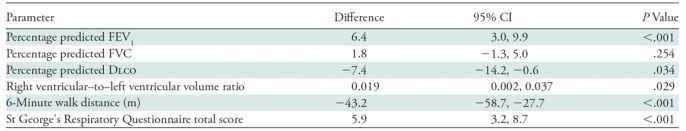

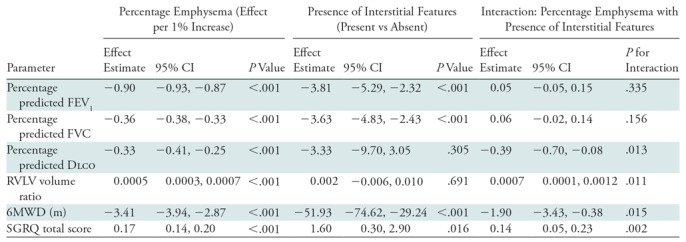

Compared with those with emphysema alone, individuals with both emphysema and interstitial features had a 6.4% higher percentage predicted FEV1 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.0%, 9.9%; P < .001), a 7.4% lower percentage predicted DLCO (95% CI: −14.2%, −0.6%; P = .034), a 0.019 higher RVLV volume ratio (95% CI: 0.002, 0.037; P = .029), a 43.2-m shorter 6MWD (95% CI: −58.7,−27.7; P < .001), and a 5.9-point higher SGRQ score (95% CI: 3.2, 8.7; P < .0001) (Figs 2–7, Table 2). In addition, as shown in Figures 2–7 and Table 3, as compared with individuals without interstitial features, in individuals with interstitial features, the percentage of lung occupied by emphysema was associated with a greater (more negative) effect on percentage predicted DLCO (P for interaction = .013) and 6MWD (P for interaction = .015), as well as a greater (more positive) effect on RVLV volume ratio (P for interaction = .011) and SGRQ score (P for interaction = .002).

Figure 2a:

Plots show association between percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and emphysema in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, and body mass index.

Figure 7a:

Plots show association between St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Table 2:

Comparison of Continuous Outcomes in Individuals with Emphysema Only versus Individuals with Emphysema and Interstitial Features

Note.—Outcomes are expressed as differences between individuals with emphysema and interstitial features compared with those with only emphysema (eg, in patients with both emphysema and interstitial features, the mean 6-minute walk distance was 43.2 meters shorter than in those with emphysema alone). All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), except for the spirometric measures, which were not adjusted for percentage predicted FEV1. CI = confidence interval, DLCO = diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide, FVC = forced vital capacity.

Table 3:

Effect of Interaction between Emphysema (Measured Continuously) and Interstitial Features (Present vs Absent) on Continuous Outcomes

Note.—Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), except for the spirometric measures, which were not adjusted for percentage predicted FEV1. CI = confidence interval, DLCO = diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide, FVC = forced vital capacity, RVLV = right ventricular to left ventricular, SGRQ = St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, 6MWD = 6-minute walk distance.

Figure 2b:

Plots show association between percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and emphysema in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, and body mass index.

Figure 3a:

Plots show association between percentage predicted forced vital capacity (FVC) and emphysema in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (percentage predicted forced vital capacity)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, and body mass index.

Figure 3b:

Plots show association between percentage predicted forced vital capacity (FVC) and emphysema in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (percentage predicted forced vital capacity)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, and body mass index.

Figure 4a:

Plots show association between percentage predicted diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide and emphysema in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (percentage predicted diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second. There were 352 data points available for diffusing capacity analysis.

Figure 4b:

Plots show association between percentage predicted diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide and emphysema in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (percentage predicted diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second. There were 352 data points available for diffusing capacity analysis.

Figure 5a:

Plots show association between right ventricular–to–left ventricular volume ratio in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (right ventricular–to–left ventricular volume ratio)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second. There were 7407 data points available for right ventricular–to–left ventricular volume ratio analysis.

Figure 5b:

Plots show association between right ventricular–to–left ventricular volume ratio in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (right ventricular–to–left ventricular volume ratio)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second. There were 7407 data points available for right ventricular–to–left ventricular volume ratio analysis.

Figure 6a:

Plots show association between 6-minute walk distance in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (meters)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Figure 6b:

Plots show association between 6-minute walk distance in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (meters)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Figure 7b:

Plots show association between St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score in individuals with and those without interstitial features. (a) Univariable additive effect of interstitial features and emphysema. SD = standard deviation. (b) Interaction between interstitial features and emphysema. Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. For a, emphysema was defined as present if more than 15% of the lung was occupied by emphysematous features. Units for β are (St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score)/(percentage emphysema). * = P for interaction given for multivariable analysis, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

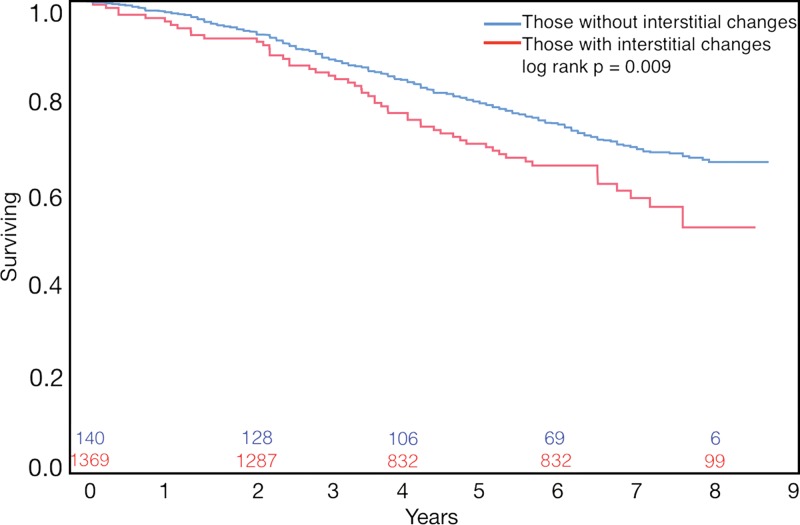

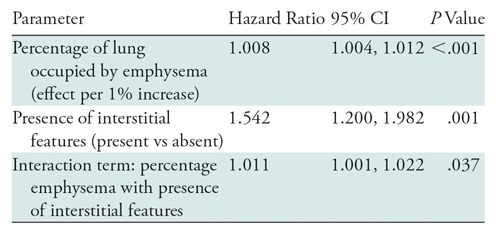

Finally, the presence of both emphysema and interstitial features was associated with an 82% greater mortality than emphysema alone (hazard ratio, 1.82; 95% CI: 1.36, 2.43, P < .001) (Fig 8), and in individuals with interstitial features, the percentage of lung occupied by emphysema was associated with a greater effect (worsening) on mortality than in those with emphysema alone (Table 4) (P for interaction = .037).

Figure 8:

Graph shows survival in individuals with emphysema only compared with that in those with both emphysema and interstitial features. Numbers on x-axis = number surviving at each time point.

Table 4:

Effect of the Interaction between Emphysema and the Presence of Interstitial Features on Mortality

Note.—Interstitial features were defined as present if more than 10% of the lung was occupied by interstitial features. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, clinical center, current smoking status, number of pack-years smoked, body mass index, percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second, and coronary calcium score. CI = confidence interval.

In the continuous-by-continuous interaction analyses, there was evidence that the percentage of interstitial features modified the effect of emphysema with regard to percentage predicted DLCO (P for interaction = .006), RVLV volume ratio (P for interaction < .001), 6MWD (P for interaction < .001), and SGRQ score (P for interaction < .001) (Table E1 [online]). Evidence of such interaction was present in the unadjusted continuous-by-continuous mortality analysis but not in the adjusted analysis (P for interaction = .004 and P for interaction = .180, respectively) (Table E2 [online]).

Discussion

Among participants in the COPDGene cohort with emphysema, the presence of interstitial features was associated with worse physiologic measures, reduced exercise capacity, worse respiratory health–related quality of life, and higher mortality. In addition, interstitial features intensified the effect of emphysema on those outcomes. These findings suggest that emphysema is more deleterious in patients with interstitial features than in those with emphysema alone. Ever-smokers with both high-attenuation features (interstitial features) and low-attenuation features (emphysema) at chest CT may be those most susceptible to the effects of chronic smoke-related injury and may be most likely to benefit from smoking cessation and pharmacologic treatment.

The relationship between emphysema and worse outcomes in COPD is well established and has been demonstrated by using both densitometric and more advanced approaches for the quantification of disease (4,5,19,27). Higher-attenuating findings on chest radiographs and at CT are also highly prevalent in smokers with COPD and smokers without COPD. For instance, a set of radiographic findings termed the “dirty chest” has long been reported in patients with COPD (28). These lesions seen on chest radiographs represent both airway abnormalities, such as increased airway wall thickness, and subtle interstitial changes that have been sometimes termed ILAs (11,28,29). Prior work (6,7,9–11,30) has demonstrated that the visual or objective presence of these ILAs on the CT images of smokers are associated with lower lung volumes, reduced exercise capacity, and higher mortality in multiple cohorts. However, their effect on the relationship between emphysema and outcomes is unknown.

At the other end of the parenchymal disease spectrum, a similar question exists of whether the presence of emphysema modifies the effect of advanced fibrosis on outcomes such as mortality and lung function decline. Although some studies have shown the combination of diseases to be associated with higher mortality compared with that in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, other studies have shown a similar or even improved survival of those with combined disease (31–37). However, in general, when there has been an association between combined disease and adverse outcomes, the relationship has been additive. That is, the rate of adverse outcomes expected is based on the total amount of lung occupied by either disease, without any effect modification of one on the other (2).

In our study, we have shown that this may not be the case, and that the presence of nonspecific interstitial features at chest CT in patients with emphysema is not only associated with an additive effect on physiologic measures such as DLCO, ancillary findings associated with pulmonary hypertension such as the RVLV volume ratio, exercise capacity, respiratory health–related quality of life, and mortality but also enhances the effect of emphysema on those outcomes. These findings suggest that high-attenuating features of smoking-related disease at CT may represent a greater susceptibility to chronic smoking-related lung injury and to the deleterious effects of that injury.

One strength of our study that may explain why we were able to identify these relationships was the use of both additive analyses and interaction terms to evaluate the effect of the presence of interstitial features on their impact on the relationship between emphysema, mortality, and other clinical measures of disease severity. In addition to the effect modification discussed above, this approach revealed other subtle but clinically relevant findings. For instance, in the additive analyses in patients with emphysema, the additional presence of interstitial features was associated with a higher percentage predicted FEV1 but no difference in percentage predicted FVC. Clinically, this results in the pseudonormalization of the FEV1/FVC ratio seen in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, which makes spirometry alone nonsensitive to these clinically relevant findings (38). This highlights the role of CT in assessing smoking-related lung disease.

It should be stressed that the interstitial features detected using our automated approach are likely not, in all cases, the true radiographic correlates of actual histopathologic fibrosis, but rather are better thought of as subclinical imaging indexes of tissue destruction, inflammation, and parenchymal remodeling in response to smoke exposure (4,6,39). Further work is needed that utilizes emphysema- and fibrosis-specific biomarkers, as well as those related to inflammation and tissue remodeling, to help determine whether the individuals at the highest risk are those with more evidence of parenchymal inflammation, fibrosis, or destruction. Our study did have several other limitations as well. The cohort studied excluded those with a diagnosis of ILD, potentially limiting the extension of these findings to those with more advanced interstitial disease (12). In addition, a limited number of participants had certain data available. For instance, DLCO was available in only 4.3% of participants, potentially limiting the interpretation of those findings. Both a limitation and a strength of this work was the use of an automated detection algorithm to identify emphysematous and interstitial features. Although we ultimately hope to make this technique widely available and implemented it using a widely available and open-source image-processing tool (3D Slicer), it remains experimental, limiting its widespread use (40). This approach did allow us to analyze a large number of CT images and to measure CT features continuously, but although we have shown this technique to have reasonable sensitivity and specificity for the detection of visually defined ILAs, it does not provide precisely the same results as visual analysis (4,6,13). Of note in this regard is the role of the cutpoints selected to define the presence of emphysema and interstitial features. As with any dichotomization of a continuous variable, there is concern of a threshold effect such that the results are due to the cutpoint selected. As shown in Appendix E1 (online), the majority of the associations between emphysema features, interstitial features, and outcomes were present in both the dichotomized analyses and the continuous-by-continuous analyses, suggesting that the findings were not cutpoint related. Of note, the mortality findings in the continuous-by-continuous analyses were statistically significant only in the unadjusted analyses. Although this may be due to the high degree of collinearity between the continuous-by-continuous interaction term and the continuous measures of emphysema and interstitial features, we cannot exclude a possible biologic or artifactual threshold effect for mortality in particular.

In summary, in our large study utilizing automated CT analysis, in those smokers with emphysema, the presence of interstitial features was associated not only with worse physiologic measures, respiratory health–related quality of life, and higher mortality, but also with an intensified deleterious effect of emphysema on those same outcomes. Further work is needed to better understand the nature of this interaction and what its underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms might be, but it does suggest that the combination of high- and low-density changes at chest CT in response to cigarette smoke exposure may indicate a particularly high susceptibility to chronic smoking-related diseases and their associated outcomes.

Summary

Among ever-smokers without interstitial lung disease, objectively identified interstitial features at chest CT enhanced the deleterious effects of emphysema on diffusing capacity, exercise capacity, quality of life, and mortality.

Implications for Patient Care

■ Even in the absence of interstitial lung disease, smokers with emphysema and interstitial features, such as reticular changes, honeycombing, centrilobular nodules, linear scar, nodular changes, subpleural lines, and ground-glass opacities, at chest CT have worse clinical disease severity and mortality than those with emphysema alone.

■ Beyond this additive effect, the presence of interstitial features enhances the deleterious effects of emphysema, highlighting the importance of identifying these subtle interstitial features and the role of CT in assessing the severity of smoking-related lung disease.

■ Because smokers with interstitial features at chest CT have worse emphysema-related outcomes, they may be those most likely to benefit from interventions such as smoking cessation.

APPENDIX

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES

Study supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL089897, R01 HL089856). The COPDGene study (NCT00608764) is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board composed of AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens, and Sunovion. Additional funding for this work includes the following National Institutes of Health grants: 5-T32-HL007633-30 (to S.Y.A. and R.K.P.), R01-HL107246 (to R.H., J.O.O., R.S.J.E., and G.R.W.), R01-HL116933 (to R.H., J.C.R., J.O.O., R.S.J.E., and G.R.W.), R01-HL111024 (to G.M.H.), P01-HL114501 (to A.M.C., I.O.R., and G.R.W.) and R01-HL089856 (to J.C.R., D.A.L., R.S.J.E., and G.R.W.). G.R.W. supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. S.Y.A. supported by the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (the I.M. Rosenzweig Junior Investigator Award).

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: For financial and nonfinancial disclosures by the authors, please see Appendix E1 (online).

Abbreviations:

- CI

- confidence interval

- COPD

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DLCO

- diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide

- FEV1

- forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FVC

- forced vital capacity

- ILA

- interstitial lung abnormality

- ILD

- interstitial lung disease

- RVLV

- right ventricular to left ventricular

- SGRQ

- St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

- 6MWD

- 6-minute walk distance

References

- 1.Auerbach O, Garfinkel L, Hammond EC. Relation of smoking and age to findings in lung parenchyma: a microscopic study. Chest 1974;65(1):29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cottin V, Hansell DM, Sverzellati N, et al. Effect of emphysema extent on serial lung function in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196(9):1162–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goddard PR, Nicholson EM, Laszlo G, Watt I. Computed tomography in pulmonary emphysema. Clin Radiol 1982;33(4):379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castaldi PJ, San José Estépar R, Mendoza CS, et al. Distinct quantitative computed tomography emphysema patterns are associated with physiology and function in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188(9):1083–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Müller NL, Staples CA, Miller RR, Abboud RT. “Density mask.” An objective method to quantitate emphysema using computed tomography. Chest 1988;94(4):782–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ash SY, Harmouche R, Putman RK, et al. Clinical and genetic associations of objectively identified interstitial changes in smokers. Chest 2017;152(4):780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Putman RK, Hatabu H, Araki T, et al. Association between interstitial lung abnormalities and all-cause mortality. JAMA 2016;315(7):672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunninghake GM, Hatabu H, Okajima Y, et al. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med 2013;368(23):2192–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle TJ, Washko GR, Fernandez IE, et al. Interstitial lung abnormalities and reduced exercise capacity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185(7):756–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Washko GR, Hunninghake GM, Fernandez IE, et al. Lung volumes and emphysema in smokers with interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med 2011;364(10):897–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Washko GR, Lynch DA, Matsuoka S, et al. Identification of early interstitial lung disease in smokers from the COPDGene Study. Acad Radiol 2010;17(1):48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD 2010;7(1):32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ash SY, Harmouche R, Ross JC, et al. The objective identification and quantification of interstitial lung abnormalities in smokers. Acad Radiol 2017;24(8):941–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahaghi FN, Vegas-Sanchez-Ferrero G, Minhas JK, et al. Ventricular geometry from non-contrast non-ECG-gated CT scans: an imaging marker of cardiopulmonary disease in smokers. Acad Radiol 2017;24(5):594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nambu A, Zach J, Schroeder J, et al. Relationships between diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and quantitative computed tomography measurements and visual assessment for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Radiol 2015;84(5):980–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan ES, Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, et al. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir Res 2014;15(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman EA, Ahmed FS, Baumhauer H, et al. Variation in the percent of emphysema-like lung in a healthy, nonsmoking multiethnic sample: the MESA lung study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11(6):898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oelsner EC, Carr JJ, Enright PL, et al. Per cent emphysema is associated with respiratory and lung cancer mortality in the general population: a cohort study. Thorax 2016;71(7):624–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder JD, McKenzie AS, Zach JA, et al. Relationships between airflow obstruction and quantitative CT measurements of emphysema, air trapping, and airways in subjects with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201(3):W460–W470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zach JA, Newell JD, Jr, Schroeder J, et al. Quantitative computed tomography of the lungs and airways in healthy nonsmoking adults. Invest Radiol 2012;47(10):596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JH, Cho MH, McDonald ML, et al. Phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity among subjects with mild airflow obstruction in COPDGene. Respir Med 2014;108(10):1469–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mets OM, van Hulst RA, Jacobs C, van Ginneken B, de Jong PA. Normal range of emphysema and air trapping on CT in young men. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199(2):336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145(6):1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shemesh J, Henschke CI, Shaham D, et al. Ordinal scoring of coronary artery calcifications on low-dose CT scans of the chest is predictive of death from cardiovascular disease. Radiology 2010;257(2):541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budoff MJ, Nasir K, Kinney GL, et al. Coronary artery and thoracic calcium on noncontrast thoracic CT scans: comparison of ungated and gated examinations in patients from the COPD Gene cohort. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2011;5(2):113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika 1982;69(1):239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han MK, Kazerooni EA, Lynch DA, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in the COPDGene study: associated radiologic phenotypes. Radiology 2011;261(1):274–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gückel C, Hansell DM. Imaging the ‘dirty lung’--has high resolution computed tomography cleared the smoke? Clin Radiol 1998;53(10):717–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirchner J, Goltz JP, Lorenz F, Obermann A, Kirchner EM, Kickuth R. The “dirty chest”--correlations between chest radiography, multislice CT and tobacco burden. Br J Radiol 2012;85(1012):339–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podolanczuk AJ, Oelsner EC, Barr RG, et al. High attenuation areas on chest computed tomography in community-dwelling adults: the MESA study. Eur Respir J 2016;48(5):1442–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jankowich MD, Rounds SIS. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome: a review. Chest 2012;141(1):222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Todd NW, Jeudy J, Lavania S, et al. Centrilobular emphysema combined with pulmonary fibrosis results in improved survival. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2011;4(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugino K, Ishida F, Kikuchi N, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema versus idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis alone. Respirology 2014;19(2):239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doherty MJ, Pearson MG, O’Grady EA, Pellegrini V, Calverley PM. Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis with preserved lung volumes. Thorax 1997;52(11):998–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jankowich MD, Rounds S. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema alters physiology but has similar mortality to pulmonary fibrosis without emphysema. Hai 2010;188(5):365–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurashima K, Takayanagi N, Tsuchiya N, et al. The effect of emphysema on lung function and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2010;15(5):843–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cottin V. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: bad and ugly all the same? Eur Respir J 2017;50(1):1700846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cottin V. The impact of emphysema in pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 2013;22(128):153–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostridge K, Williams N, Kim V, et al. Distinct emphysema subtypes defined by quantitative CT analysis are associated with specific pulmonary matrix metalloproteinases. Respir Res 2016;17(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging 2012;30(9):1323–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.