Highlights

-

•

The estimated recent tuberculosis (TB) transmission rate (clustering rate of 41.2%) was found to be high in Ghana.

-

•

There is a need for increased TB awareness by the national tuberculosis control program.

-

•

Mycobacterium africanum (MAF) transmits at a lower rate compared to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Ghana.

-

•

The incidence of MAF remained fairly constant over the study years.

-

•

Other factors may likely be responsible for maintaining MAF in West Africa.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium africanum, Transmission, Molecular epidemiology, MIRU-VNTR, Spoligotyping

Abstract

Objective

Understanding transmission dynamics is useful for tuberculosis (TB) control. A population-based molecular epidemiological study was conducted to determine TB transmission in Ghana.

Methods

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) isolates obtained from prospectively sampled pulmonary TB patients between July 2012 and December 2015 were characterized using spoligotyping and standard 15-locus mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit variable number tandem repeat (MIRU-VNTR) typing for transmission studies.

Results

Out of 2309 MTBC isolates, 1082 (46.9%) unique cases were identified, with 1227 (53.1%) isolates belonging to one of 276 clusters. The recent TB transmission rate was estimated to be 41.2%. Whereas TB strains of lineage 4 belonging to M. tuberculosis showed a high recent transmission rate (44.9%), reduced recent transmission rates were found for lineages of Mycobacterium africanum (lineage 5, 31.8%; lineage 6, 24.7%).

Conclusions

The study findings indicate high recent TB transmission, suggesting the occurrence of unsuspected outbreaks in Ghana. The observed reduced transmission rate of M. africanum suggests other factor(s) (host/environmental) may be responsible for its continuous presence in West Africa.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global health emergency; in 2016 an estimated 10.4 million people got sick, while 1.7 million died of TB (WHO, 2017). In 1993, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared TB a global health emergency and called for more efforts and resources to fight TB. Due largely to the inefficacy of the bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine against pulmonary TB in adults, the current TB control strategy relies on case detection and treatment under the directly observed therapy short course (DOTs) strategy. The conventional indicators used to assess national control programs under this strategy focus on the proportion of cases that are cured at the end of treatment or whose sputum microscopy becomes negative after the first 2 months of treatment. Such indicators ignore equally important aspects of TB control, which include the duration of infectivity, the frequency of reactivation, and the risk of progression among the infected contacts, as well as the proportion of TB due to recent transmission.

Understanding transmission dynamics will contribute to knowledge on factors that enhance the spread of the disease, which is useful for developing preventive interventions. Molecular epidemiological studies have been very useful in a number of countries, identifying populations at risk and areas of high transmission, as well as providing much understanding on the prevalence of different Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) strains with varied virulence and drug resistance rates (Anderson et al., 2014, Malm et al., 2017, Seto et al., 2017, Varghese et al., 2013, Walker et al., 2014, Yang et al., 2016). These studies have shown that the dynamics of TB transmission vary greatly geographically. Even though Africa harbors a large proportion of the global TB cases, with a current incidence of 254 per 100 000 population (WHO, 2017), population-based molecular epidemiological studies needed to understand transmission patterns are rare. The few studies conducted have not been population-based and have lacked an in-depth analysis of the transmission dynamics of MTBC strains belonging to different lineages (Asante-Poku et al., 2016, Glynn et al., 2010, Mulenga et al., 2010).

The molecular typing tools – spacer oligonucleotide typing (spoligotyping) and mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit variable number tandem repeat (MIRU-VNTR) typing – have been used successfully for strain differentiation in TB transmission studies due to their combined high discriminatory power and reproducibility; furthermore, in combination with epidemiological data, they have been used for the detection of recent TB transmission and outbreaks (Anderson et al., 2014, Barnes and Cave, 2003, Maguire et al., 2002, Surie et al., 2017, Varghese et al., 2013). Currently, the high cost and expertise needed for whole genome sequencing and analysis have precluded its use in population-based studies, and considering capacity building in a low-resource setting like Ghana, spoligotyping and MIRU-VNTR typing remain good alternatives.

TB in humans is caused mainly by Mycobacterium tuberculosis sensu stricto (MTBss) and Mycobacterium africanum (MAF), which are further divided into seven lineages: MTBss lineages 1–4 and 7 (L1–L4 and L7); MAF lineages 5 and 6 (L5 and L6) (Blouin et al., 2012, de Jong et al., 2010). While MTBss is distributed globally, MAF is restricted to West Africa, where it is responsible for up to 50% of TB cases (Gagneux and Small, 2007). Nevertheless, reports mainly from the Gambia where L6 is prevalent, suggest MAF is attenuated compared to MTBss, hence could be outcompeted by MTBss (de Jong et al., 2010, de Jong et al., 2008, Kallenius et al., 1999). However, an 8-year study recently conducted in Ghana found the prevalence of MAF to be fairly constant at approximately 20%, indicating that MAF and MTBss may be transmitted equally (Yeboah-Manu et al., 2016). The objective of this study was to determine the transmission dynamics of TB caused by MTBss and MAF in Ghana.

Methods

Study design and population

This study was a population-based prospective study in which sputum samples were collected from consecutive clinically diagnosed pulmonary TB patients reporting to 12 selected health facilities within an urban setting (Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA)) and the rural setting of East Mamprusi District (MamE) (Supplementary material, Figure S1). The study was conducted from July 2012 to December 2015. A pulmonary TB case was defined as an individual with a case of TB that was confirmed both clinically and bacteriologically. Detailed demographic and epidemiological data were obtained from consented participants.

Mycobacterial isolation, species identification, and drug susceptibility testing

The sputum samples were decontaminated and cultured on Lowenstein–Jensen medium to obtain mycobacterial isolates. These isolates were confirmed as MTBC by detecting the MTBC-specific insertion sequence IS6110 using PCR (Yeboah-Manu et al., 2001). In vitro drug susceptibility to isoniazid and rifampicin were determined using either the microplate Alamar Blue cell viability assay, as described elsewhere (Otchere et al., 2016), and/or the GenoType MTBDRplus assay (Hain Lifescience), following the manufacturer’s protocol (Barnard et al., 2008).

Lineage and strain classification

Lineage and strain classification of the MTBC was achieved in a stepwise manner using large sequence polymorphism typing identifying regions of difference 4, 9, 12, 702, and 711 (de Jong et al., 2010, Gagneux and Small, 2007), single nucleotide polymorphism typing, spoligotyping (Kamerbeek et al., 1997), and MIRU-VNTR typing (Supply et al., 2006). For MIRU-VNTR typing, a customized set of 8 MIRU loci was first used, as described by Asante-Poku et al. (2014), and clustered cases were resolved by analyzing the remaining 7 loci of the standard MIRU-15 loci set (Supply et al., 2006). All assays were well controlled with PCR amplifications and pre-PCR procedures conducted in physically separated compartments to avoid laboratory cross-contamination. The presence of more than one allelic repeat number (multiple allele) for any given locus is suggestive of laboratory cross-contamination, multiple strain infection, or microevolution of a single strain. To prevent bias resulting from cross-contamination and multiple strain infection, isolates with multiple alleles at more than one MIRU locus (described as ‘untypeable’) were excluded from further analysis. Isolates with only one multiple allele at any given locus were, however, included due to the possibility of microevolution.

The spoligotyping patterns and assigned shared type numbers obtained were defined according to the SITVITWEB database (http://www.pasteur-guadeloupe.fr: 8081/SITVIT_ONLINE/), while sub-lineages were assigned based on the MIRU-VNTRplus database (http://www.miru-vntrplus.org) (Allix-Beguec et al., 2008). Strains with no lineage nomenclature data were further identified using the TB lineage database (Shabbeer et al., 2012) or otherwise regarded as orphan strains. A strain was defined as an MTBC isolate with a unique molecular signature, and thus a unique spoligotype pattern and/or a unique MIRU-VNTR allelic pattern for the number of investigated MIRU loci.

Clustering analysis and risk factor assessment

Clustering analysis was performed using the categorical parameter and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) coefficient from a constructed phylogenetic tree using the online MIRU-VNTR tool. Clustering analysis was based on the assumption that strains with the same DNA fingerprint may be epidemiologically linked and associated with recent TB transmission (Hall, 1996). A cluster was defined as two or more isolates (same strain) that share an indistinguishable spoligotype and 15-locus MIRU-VNTR allelic pattern, but allowing for one missing allelic data at any one of the difficult-to-amplify MIRU loci (VNTR 2163, 3690, and 4156). The size of a cluster was also defined using the total number of isolates in the cluster classified into categories of small (2 isolates), medium (3–5 isolates), large (6–20 isolates), and very large (>20 isolates).

The recent transmission rate was estimated using the n − 1 formula (Glynn et al., 1999): , where nc is the total number of clustered cases, c is the number of clusters, and n is the total number of cases in the sample.

Only one strain per participant was included in the analysis, and follow-up cases were excluded. The clustering analysis was stratified first by location and then by MTBC lineage. The spatial distribution and clustering among all of the observed Spoligo/MIRU strain types were studied by constructing a minimum spanning tree (MST) with Bionumerics software (Applied Maths, Sint-Marteen-Latem, Belgium).

Data management and analysis

Both molecular and epidemiological data were analyzed. Epidemiological data retrieved from all participants with positive MTBC cultures were included in the analysis while excluding data from those with no growth, contaminated cultures, and isolated non-tuberculous mycobacterial species. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Stata statistical package version 14.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). The association of specific lineages and/or sub-lineages of the MTBC with time and/or geographical locations were explored using the Chi-square test and a logistic regression model. For the determination of independent predictive factors for recent TB transmission, a multivariate analysis (forward stepwise approach with a probability entry of 0.1) was conducted using a logistic regression model while estimating the odds ratios (OR). p-Values of <0.05 were considered significant.

The study is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Molecular Epidemiology for Infectious Diseases (STROME-ID) guidelines (Field et al., 2016).

Results

Characteristics of study participants

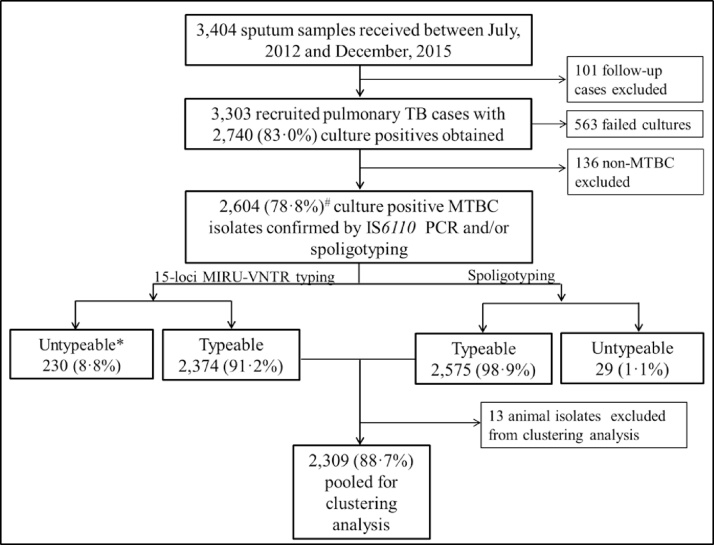

A total 3303 sputum smear-positive pulmonary TB cases were recruited, 382 (11.6%) from the rural setting and 2921 (88.4%) from the urban setting; 2604 (78.8%) MTBC isolates were obtained from these cases (Supplementary material, Table S1). After excluding 13 Mycobacterium bovis and isolates that were untypeable (described in the Methods section), 2309 of 2604 isolates (88.7%) were included for clustering analysis. The participants comprised 1631 (71%) males and 663 (29%) females (there was no record of sex for 15 participants) with a median age of 39 years (range 3–91 years) and 33 years (range 4–90 years), respectively (Figure 1; Supplementary material, Table S1). The male-to-female ratio observed was comparable to the national average of approximately 2:1.

Figure 1.

Pipeline for recruited participants and culture-positive TB cases included in the clustering analysis.

*Category described as untypeable for MIRU-VNTR includes isolates with ≥2 MIRU loci unamplified (n = 164, 71.3%) and isolates with a double allele at ≥2 MIRU loci (n = 66, 28.7%). These isolates were described as suspected mixed infection or laboratory contamination and hence were excluded from further analysis.

#Frequency was expressed as the total number of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) isolates obtained.

Of the 2309 participants with MTBC genotyping results, 201 (8.7%) were from the rural setting and 2108 (91.3%) from the urban setting. Among this study cohort, 7.4% (184/2482) of participants were previously treated cases including relapse, which is similar to the national value of 7.0% (WHO, 2015). Seventy-one percent (1561/2208) presented with a sputum smear microscopy bacterial burden result of at least 2+ and 33% (544/1665) admitted having contact with at least one TB patient. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, it was found that male patients were less likely to be infected with a L5 strain (adjusted OR 0.7, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.5–0.9) and individuals living in villages were more likely to be infected with a L6 strain (OR 6.6, 95% CI 1.2–36.1) (Supplementary material, Table S2).

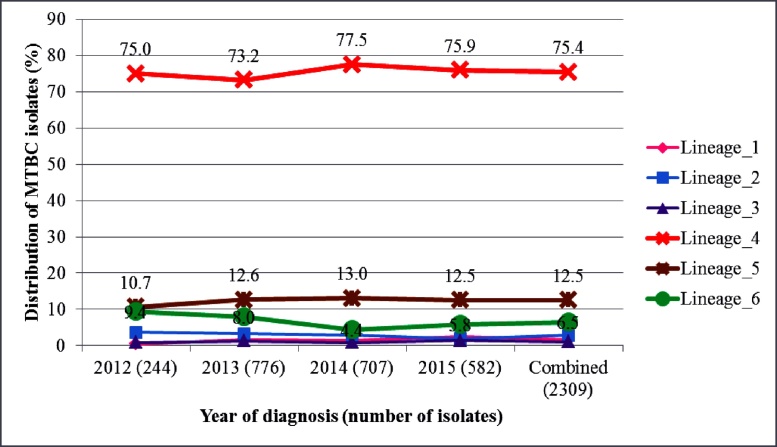

Population structure and recent transmission rate estimation

Among the 2309 MTBC isolates analyzed for clustering, 1870 (81.0%) were MTBss and 439 (19.0%) were MAF. Six of the seven human-adapted MTBC lineages were found, with L4, L5, and L6 being most frequent: 1741 (75.4%), 289 (12.5%), and 150 (6.5%) isolates, respectively (Table 1). The relative proportions of the most frequent MTBC lineages remained constant over the entire 3.5-year study period (ptrend: L4 p = 0.72, L5 p = 0.84, L6 p = 0.25; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Geographical distribution and population structure of MTBC in Ghana by spoligotyping.

| Rural, n (%) | Urban, n (%) | Combined, n (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTBC isolates | 204 (8.8) | 2118 (91.2) | 2322 |

| Species distribution | |||

| M. tuberculosis | 172 (9.2) | 1698 (90.8) | 1870 (80.5) |

| M. africanum | 29 (6.6) | 410 (93.4) | 439 (18.9) |

| Animal | 3 (23.1) | 10 (76.9) | 13 (0.6) |

| Human adapted MTBC lineage distribution | |||

| Lineage_1 | 4 (10.5) | 34 (89.5) | 38 (1.6) |

| Lineage_2 | 14 (21.5) | 51 (78.5) | 65 (2.8) |

| Lineage_3 | 1 (3.8) | 25 (96.2) | 26 (1.1) |

| Lineage_4 | 153 (8.8) | 1588 (91.2) | 1741 (75.4) |

| Lineage_5 | 15 (5.2) | 274 (94.8) | 289 (12.5) |

| Lineage_6 | 14 (9.3) | 136 (90.7) | 150 (6.5) |

| Lineage_4 sub-lineage distribution | |||

| Cameroon | 77 (7.4) | 969 (92.6) | 1046 (60.1) |

| Ghana | 50 (13.3) | 326 (86.7) | 376 (21.6) |

| Haarlem | 12 (7.7) | 144 (92.3) | 156 (9.0) |

| LAM | 7 (14.0) | 43 (86.0) | 50 (2.9) |

| Uganda | 1 (2.5) | 39 (97.5) | 40 (2.3) |

| Other (S, U, X, NEW-1) | 5 (9.8) | 46 (90.2) | 51 (2.9) |

| Not determined | 1 (4.5) | 21 (95.5) | 22 (1.3) |

MTBC, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

Proportions stated here are column-wise distributions with respect to the categories of species, lineages or sub-lineages.

Figure 2.

Temporal distribution of 2309 Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) isolates stratified by lineage. Lineages are color-coded with the universally accepted color codes for the main MTBC lineages.

Of the 2309 isolates included for clustering analysis, 1227 (53.1%) isolates clustered in 276 different clusters with a mean cluster size of 4 (range 2–35) and 1082 (46.9%) unique isolates were identified, giving a total of at least 1358 different MTBC strains circulating within the study population (Table 2a). Using the n − 1 method, the overall clustering rate (reflecting the recent transmission rate) was estimated to be 41.2%. Lineages 2, 4, and 5 contributed high clustering rates of 53.8%, 44.9%, and 31.8%, respectively (Table 2a). The Cameroon, Ghana, and Haarlem sub-lineages of L4 were the most abundant sub-lineages and, compared to the LAM sub-lineage, contributed significantly to the observed high L4 clustering rate (p < 0.05) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference in the clustering rate between the Cameroon and Ghana sub-lineages (p = 0.57) (Figure 3). While no significant difference in the recent transmission rates was seen between members of MAF (L5 and L6, p = 0.118), it was found that L4 was transmitted significantly more (p < 0.001), with seven of its clusters having very large cluster sizes (>20 isolates per cluster) made up of the Ghana sub-lineage (four very large clusters) and Cameroon sub-lineage (three very large clusters) (Figure 3; Supplementary material, Figure S2). Notwithstanding the lower transmissibility of L5 and L6 compared to L4, four large clusters were also observed for each of these lineages. The urban and rural settings had estimated recent transmission rates of 41.7% and 9.0%, respectively.

Table 2a.

Clustering analysis stratified by lineages and major sub-lineage populations of MTBC.

| Lineage | Isolates (n) | Clustered cases (c) | Clustered strains (nc) | Single cases (s) | Total strain types (s + c) | Clustering ratea (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineage 1 | 38 | 3 | 7 | 31 | 34 | 10.5 |

| Lineage 2 | 65 | 8 | 43 | 22 | 30 | 53.8 |

| Lineage 3 | 26 | 2 | 4 | 22 | 24 | 7.7 |

| Lineage 4 | 1741 | 201 | 982 | 759 | 960 | 44.9 |

| Cameroonb | 1046 | 123 | 614 | 432 | 555 | 46.9 |

| Ghanab | 376 | 36 | 206 | 170 | 206 | 45.2 |

| Haarlemb | 156 | 23 | 91 | 65 | 88 | 43.6 |

| LAMb | 50 | 6 | 25 | 25 | 31 | 38.0 |

| Ugandab | 40 | 5 | 16 | 24 | 29 | 27.5 |

| Lineage 5 | 289 | 51 | 143 | 146 | 197 | 31.8 |

| Lineage 6 | 150 | 11 | 48 | 102 | 113 | 24.7 |

| Summaryc | 2309 | 276 | 1227 | 1082 | 1358 | 41.2 |

MTBC, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

The clustering rate was used to estimate the recent transmission rate.

Major lineage 4 sub-population.

The summary was calculated using only the items in cells corresponding to the six main lineages.

Figure 3.

Cluster distribution and size stratified by lineage (panel A and C) and sub-lineage (panel B and D). *p < 0.001, #p = 0.118, ¤p = 0.565.

Exploring the diversity and clustering within the MTBC lineages

Very large molecular clusters (clusters with >20 isolates; defined in the Methods section) were observed for L4, in addition to one strikingly large cluster belonging to the Beijing family of lineage 2 (Figure 4; Supplementary material, Figure S3). Generally, only a few multidrug-resistant MTBC strains were observed across all the major lineages (Supplementary material, Figures S4–S6). There was no single large cluster with all isolates being multidrug-resistant (Supplementary material, Figure S4). The spatial distributions of the isolates constituting each cluster stratified by study setting are shown in the Supplementary material, Figures S7–S9.

Figure 4.

Minimum spanning tree (MST) representation of the clustering of 2322 Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) isolates from Accra Metropolitan Assembly and East Mamprusi District built with Bionumerics software. The color code reflects the main MTBC lineages 1 to 6 with the size depicting the number of clustered isolates with an identical strain type.

Molecular epidemiology and factors associated with clustering: logistic regression modeling

Risk factors associated with recent TB transmission were sought. A total of 675 individuals belonging to either large (6–20 isolates) or very large (>20 isolates) molecular clusters were identified, with a combined median cluster size of 14 (range 6–35). The majority of the individuals belonging to very large clusters were male, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 3:1, significantly higher than the 2:1 ratio observed in the general TB patient population (p = 0.022). Three large clusters – cluster ID MSC4193, MSC5003.X, and MSC4107, with cluster sizes of 9, 7, and 7 respectively – involved only male subjects (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of large molecular clusters resulting from combined 15-MIRU and spoligotyping cluster analysis.

| Number | Cluster codea | Number of cases in cluster | Sex, male: female | Median age (IQR) | Diagnosis lapseb (months) | Same residential districtc | Known risk factor (number)d | Lineage (sub-lineage) | Drug resistancee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MSC4063.X | 35 | 31:4 | 34 (26–44) | 40 | 7/5/5/4/4/5 | Smoking (6) Other (8) |

L4 (Cameroon) | 3 |

| 2 | MSC4060.X | 34 | 24:10 | 34 (25–45) | 41 | 6/4/3/3/3/3 | Smoking (6) Other (5) |

L4 (Cameroon) | 4 |

| 3 | MSC4045.X | 30 | 26:4 | 40 (29–48) | 39 | 7/3/3/3/3 | Smoking (5) HIV (4) Other (3) |

L4 (Cameroon) | 2 |

| 4 | MSC2001 | 27 | 22:5 | 35 (27–48) | 37 | 8/5 | Smoking (8) HIV (4) Other (2) |

L2 (Beijing) | 1 |

| 5 | MSC4031 | 26 | 19:7 | 41 (33–52) | 36 | 6/4/3 | Smoking (6) HIV (3) Other (1) |

L4 (Ghana) | 11 |

| 6 | MSC4110 | 26 | 21:5 | 38 (28–51) | 39 | 6/3 | Smoking (5) HIV (1) Other (4) |

L4 (Ghana) | ND |

| 7 | MSC4095 | 24 | 16:8 | 35 (24–45) | 39 | 7/6 | Smoking (5) Other (2) |

L4 (Ghana) | 9 |

| 8 | MSC4027 | 21 | 16:5 | 27 (25–45) | 40 | 6/3 | Smoking (3) | L4 (Ghana) | 3 |

| 9 | MSC4063.3 | 19 | 18:1 | 28 (21–45) | 41 | 5/5 | Smoking (7) | L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 10 | MSC4063.18 | 18 | 10:7 | 35 (24–41) | 36 | 6/3 | Smoking (4) HIV (1) |

L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 11 | MSC4013 | 15 | 13:2 | 42 (32–55) | 32 | 4/3 | Smoking (3) HIV (2) Other (2) |

L4 (Haarlem) | 2 |

| 12 | MSC4136 | 15 | 13:2 | 36 (28–44) | 34 | 6 | Smoking (2) HIV (1) Other (3) |

L4 (Haarlem) | ND |

| 13 | MSC4040 | 14 | 8:6 | 31 (27–45) | 33 | 3/3 | HIV (1) Other (4) |

L4 (Cameroon) | 1 |

| 14 | MSC4069.X | 14 | 11:3 | 27 (23–38) | 34 | 6/3 | Smoking (2) HIV (2) Other (1) |

L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 15 | MSC4073 | 14 | 9:5 | 40 (29–47) | 24 | 5/4 | Smoking (3) | L4 (Cameroon) | 3 |

| 16 | MSC5002.X | 14 | 7:7 | 40 (38–53) | 28 | 5 | HIV (2) Smoking (1) |

L5 (West African I) | 2 |

| 17 | MSC4063.2 | 13 | 8:4 | 37 (27–44) | 38 | 4 | Smoking (2) Other (3) |

L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 18 | MSC4068.X | 13 | 9:4 | 35 (30–44) | 27 | 5/3 | Smoking (6) HIV (2) Other (2) |

L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 19 | MSC4024 | 12 | 6:5 | 28 (26–42) | 37 | 3 | Smoking (2) Other (1) |

L4 (X3) | 4 |

| 20 | MSC4060.18 | 12 | 7:5 | 35 (32–40) | 36 | 3/3 | Smoking (2) HIV (2) Other (3) |

L4 (Cameroon) | 1 |

| 21 | MSC4063.17 | 12 | 7:5 | 26 (24–51) | 39 | ND | Smoking (4) HIV (1) Other (3) |

L4 (Cameroon) | 2 |

| 22 | MSC4138 | 11 | 7:4 | 41 (30–48) | 28 | 4 | Smoking (4) | L4 (LAM) | ND |

| 23 | MSC4069.3 | 10 | 5:5 | 32 (24–39) | 31 | 3 | Smoking (1) HIV (1) |

L4 (Cameroon) | 2 |

| 24 | MSC4104 | 10 | 7:2 | 35 (25–54) | 34 | 5 | Smoking (3) Other (1) |

L4 (Ghana) | 6 |

| 25 | MSC6006 | 10 | 4:6 | 41 (35–47) | 33 | 5/3 | Smoking (1) Other (2) |

L6 (West African II) | ND |

| 26 | MSC4045.3 | 9 | 7:2 | 43 (32–50) | 33 | 3 | Smoking (1) Other (1) |

L4 (Cameroon) | 1 |

| 27 | MSC4060.21 | 9 | 6:3 | 32 (26–43) | 22 | ND | HIV (1) Other (2) |

L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 28 | MSC4060.3 | 9 | 5:4 | 32 (25–53) | 34 | 3 | Smoking (1) Other (2) |

L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 29 | MSC4193 | 9 | 9:0 | 36 (30–41) | 28 | ND | Smoking (6) HIV (1) Other (2) |

L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 30 | MSC4068.3 | 8 | 6:2 | 45 (34–54) | 27 | 2 | Smoking (2) HIV (1) Other (1) |

L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 31 | MSC4022 | 7 | 6:1 | 50 (46–62) | 36 | 4 | Smoking (1) Other (1) |

L4 (Haarlem) | ND |

| 32 | MSC4060.4 | 7 | 3:4 | 34 (30–49) | 22 | 5 | Smoking (1) | L4 (Cameroon) | ND |

| 33 | MSC4080.13 | 7 | 4:3 | 24 (17–50) | 20 | 3 | Smoking (1) | L4 (Cameroon) | 1 |

| 34 | MSC4082 | 7 | 6:1 | 35 (28–40) | 33 | 3 | Smoking (1) | L4 (Ghana) | ND |

| 35 | MSC4107 | 7 | 7:0 | 38 (29–53) | 28 | 3/3 | Smoking (2) Other (1) |

L4 (Ghana) | 1 |

| 36 | MSC5003.2 | 7 | 4:3 | 35 (26–57) | 33 | ND | HIV (1) | L5 (West African I) | 1 |

| 37 | MSC5003.X | 7 | 7:0 | 43 (26–66) | 34 | 3 | Smoking (2) Other (1) |

L5 (West African I) | ND |

| 38 | MSC6004 | 7 | 5:2 | 44 (36–50) | 31 | ND | HIV (1) Other (3) |

L6 (West African II) | 3 |

MIRU, mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit; L2, lineage 2; L4, lineage 4; L5, lineage 5; L6, lineage 6; ND, none determined; IQR, interquartile range.

Cluster codes in bold font involved evidence of household transmission.

Time lapse (in months) between first diagnosed case and last diagnosed case.

Number of participants with the same district of residence. Only >2 individuals in the same residential district are indicated. ‘/’ is used to separate individuals from different districts.

‘Other’ in this category refers to alcohol or substance abuse.

Number of participants carrying strains with drug resistance to either isoniazid or rifampicin.

Epidemiological investigations revealed both localized and dispersed recent transmission among the clustered cases, with suggested evidence of household transmission in at least six large clusters (MSC4063.X, MSC2001, MSC4095, MSC4063.18, MSC4069.X, and MSC4104). Specifically, the same L4 strain (part of cluster MSC4069.X) was found among three individuals belonging to the same household, with the oldest person (age 49 years) reporting having contact with his son who had TB 4 months prior to his episode (suggestive of household transmission). The majority of the large clusters involved TB strains circulating over almost the entire study period (Supplementary material, Figure S10). Apart from three Ghana sub-lineage clusters (MSC4104, MSC4031, and MSC4095) and one L6 cluster (MSC6004), with respectively 60% (6/10), 42% (11/26), 38% (9/24), and 43% (3/7) of isolates showing resistance to rifampicin and/or isoniazid (Table 3), such high levels of drug resistance were not observed in the other large and very large clusters. Only 2% of the isolates belonging to large and very large clusters were multidrug-resistant TB strains and this was significantly lower than that for small (2 isolates) and medium (3–5 isolates) (4%) clusters (p = 0.031).

For the determination of possible factors associated with recent TB transmission, a general logistic regression model including all MTBC lineages was first performed, using the event of belonging to a clustered case as the outcome variable and participant variables as possible predictors (Table 4). In a separate logistic regression model, risk factors associated with recent TB transmission were tested stratified independently by L4 and L5 (Table 5), excluding L6 due to the limited sample size. In the multivariable analysis for the general logistic regression model, it was found that harboring either an isoniazid- or rifampicin-resistant MTBC strain (adjusted OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.5–0.9) was associated with a lower odds of belonging to a clustered case (Table 4). All other factors such as education status, occupation, income level, ethnicity, religion, and HIV status had no association with recent TB transmission.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors associated with TB clustering (recent TB transmission).

| Variable | MTBC (N = 2309) |

Univariate |

Multivariatea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total TB cases, n (%) | Clustered casesb, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Year diagnosed | 2309 (100) | 1229 (53·2) | ||||

| 2012 | 244 (10·6) | 147 (60·3) | 1·4 (1·0–1·8) | 0·043 | 1·3 (0·9–1·7) | 0·113 |

| 2013 | 776 (33·6) | 410 (52·8) | Reference | |||

| 2014 | 707 (30·6) | 365 (51·6) | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 0·642 | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·203 |

| 2015 | 582 (25·2) | 307(52·8) | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 0·975 | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 0·703 |

| Sex | 2294 (99·4) | |||||

| Male | 1631 (71·1) | 863 (52·9) | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 0·685 | ||

| Female | 663 (28·9) | 357 (53·8) | Reference | |||

| Age (years)c | 2224 (96·3) | |||||

| <15 | 37 (1·7) | 25 (67·6) | 1·6 (0·8–3·3) | 0·183 | 1·6 (0·8–3·2) | 0·221 |

| 15–29 | 639 (28·7) | 360 (56·3) | Reference | |||

| 30–39 | 570 (25·6) | 307 (53·9) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·387 | 0·9 (0·7–1·2) | 0·688 |

| 40–59 | 778 (35·0) | 398 (51·2) | 0·8 (0·7–1·0) | 0·052 | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·241 |

| >59 | 200 (9·0) | 97 (48·5) | 0·7 (0·5–1·0) | 0·053 | 0·9 (0·6–1·1) | 0·211 |

| Nationality | 1781 (77·1) | |||||

| Ghanaian | 1714 (96·2) | 932 (54·4) | Reference | |||

| Other | 67 (3·8) | 38 (56·7) | 1·1 (0·7–1·8) | 0·706 | ||

| Locality | 2309 (100) | 1229 (53·2) | ||||

| Rural | 201 (8·7) | 74 (36·8) | Reference | |||

| Urban | 2108 (91·3) | 1155 (54·8) | 2·1 (1·5–2·8) | <0·001 | ||

| Residence classification | 1642 (71·1) | |||||

| Village | 69 (4·2) | 27 (39·1) | 0·5 (0·3–0·8) | 0·007 | ||

| Town | 182 (11·1) | 96 (52·7) | 0·9 (0·6–1·2) | 0·415 | ||

| City residential area | 52 (3·2) | 27 (51·9) | 0·8 (0·5–1·5) | 0·564 | ||

| City suburb | 1136 (69·2) | 636 (56·0) | Reference | |||

| City slum | 203 (12·4) | 112 (55·2) | 1·0 (0·7–1·3) | 0·83 | ||

| Residential district | 1538 (66·6) | |||||

| Ablekuma | 545 (35·4) | 298 (54·7) | Reference | |||

| Ashiedu Keteke | 170 (11·1) | 100 (58·8) | 1·2 (0·8–1·7) | 0·343 | ||

| Ayawaso | 220 (14·3) | 124 (56·4) | 1·1 (0·8 to 1·5) | 0·672 | ||

| Kpeshie | 224(14·6) | 121 (54·0) | 1·0 (0·7–1·3) | 0·867 | ||

| Mamprusi East | 70 (4·6) | 22 (31·4) | 0·4 (0·2–0·6) | <0·001 | ||

| Okaikoi | 176 (11·4) | 98 (55·7) | 1·0 (0·7 to 1·5) | 0·816 | ||

| Osu Klottey | 133 (8·6) | 78 (58·7) | 1·2 (0·8–1·7) | 0·409 | ||

| Household type | 1624 (70·3) | |||||

| Self-contained | 412 (25·4) | 221 (53·6) | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 0·797 | ||

| Compound house | 1212 (74·6) | 659 (54·4) | Reference | |||

| Education | 1748 (75·7) | |||||

| Primary | 222 (12·7) | 125 (56·3) | 1·1 (0·8–1·5) | 0·637 | ||

| Middle/JHS | 637 (36·4) | 347 (54·5) | Reference | |||

| Secondary | 429 (24·5) | 232 (54·1) | 1·0 (0·8–1·3) | 0·899 | ||

| Tertiary | 190 (10·9) | 110 (57·9) | 1·1 (0·8–1·6) | 0·405 | ||

| No education | 270 (15·4) | 141 (52·2) | 0·9 (0·7–1·2) | 0·534 | ||

| Occupation | 1722 (74·6) | |||||

| Unemployed | 390 (22·6) | 208 (53·3) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·423 | ||

| Unskilled | 951 (55·2) | 530 (55·7) | Reference | |||

| Skilled | 381 (22·1) | 198 (52·0) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·213 | ||

| Monthly income (GH) | 1622 (70·2) | |||||

| None | 371 (22·9) | 213 (57·4) | Reference | |||

| <301 | 807 (49·7) | 438 (54·3) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·315 | ||

| 301–1000 | 407 (25·1) | 218 (53·6) | 0·8 (0·6–1·1) | 0·281 | ||

| >1000 | 37 (2·3) | 15 (40·5) | 0·5 (0·3–1·0) | 0·052 | ||

| Religion | 1771 (76·7) | |||||

| Christian | 1361 (76·9) | 739 (54·3) | Reference | |||

| Islam | 302 (17·0) | 161 (53·3) | 1·0 (0·7–1·2) | 0·755 | ||

| Other | 26 (1·5) | 14 (53·9) | 1·0 (0·4–2·1) | 0·963 | ||

| Not religious | 82 (4·6) | 49 (59·7) | 1·2 (0·8–2·0 | 0·366 | ||

| Ethnicity | 1760 (76·4) | |||||

| Akan | 570 (32·3) | 309 (54·2) | Reference | |||

| Ewe | 259 (14·7) | 143 (55·2) | 1·0 (0·8–1·4) | 0·788 | ||

| Ga/Adangbe | 544 (30·8) | 310 (57·0) | 1·1 (0·9–1·4) | 0·352 | ||

| Other | 392 (22·2) | 196 (50·0) | 0·8 (0·6–1·1) | 0·199 | ||

| Marital status | 1758 (76·1) | |||||

| Single | 766 (43·6) | 431 (56·3) | Reference | |||

| Married | 742 (42·2) | 395 (53·2) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·237 | ||

| Divorced | 167 (9·5) | 99 (59·3) | 1·1 (0·8–1·6) | 0·476 | ||

| Widowed | 83 (4·7) | 35 (42·2) | 0·6 (0·3–0·9) | 0·015 | ||

| Smear positivity | 2208 (95·6) | |||||

| Scanty 1–9 | 173 (7·8) | 96 (55·5) | 1·1 (0·8–1·5) | 0·714 | ||

| 1+ | 474 (21·5) | 237 (50·0) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·151 | ||

| 2+ | 546 (24·7) | 294 (53·9) | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 0·957 | ||

| 3+ | 1015 (46·0) | 548 (54·0) | Reference | |||

| Previous TB treatment | 1737 (75·2) | |||||

| Yes | 291 (16·8) | 153 (52·6) | 0·9 (0·7–1·2) | 0·535 | ||

| No | 1446 (83·2) | 789 (54·6) | Reference | |||

| Risk of TB contact | ||||||

| Close friend/household | 1665 (72·1) | |||||

| No contact | 1121 (67·3) | 594 (53·0) | Reference | |||

| 1 contact | 212 (12·7) | 118 (55·7) | 1·1 (0·8–1·5) | 0·475 | ||

| 2–5 contacts | 309 (18·6) | 179 (57·9) | 1·2 (0·9–1·6) | 0·123 | ||

| 6–10 contacts | 23 (1·4) | 15 (65·2) | 1·7 (0·7–4·0) | 0·249 | ||

| Imprisonment | 1660 (71·9) | |||||

| Yes | 97 (5·8) | 56 (57·7) | 1·1 (0·8–1·7) | 0·513 | ||

| No | 1563 (94·2) | 849 (54·3) | Reference | |||

| Health/laboratory worker | 1661 (71·9) | |||||

| Yes | 47 (2·8) | 25 (53·2) | 0·9 (0·5–1·7) | 0·85 | ||

| No | 1614 (97·2) | 881 (54·6) | Reference | |||

| Immunosuppressive condition | 1695 (73·4) | |||||

| Any | 893 (52·7) | 488 (54·6) | 1·0 (0·9–1·2) | 0·747 | ||

| None | 802 (47·3) | 432 (53·9) | Reference | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 534 (23·1) | |||||

| Yes | 104 (19·5) | 54 (51·9) | 1·0 (0·7–1·5) | 0·957 | ||

| No | 430 (80·5) | 222 (51·6) | Reference | |||

| HIV status | 1166 (50·5) | |||||

| Positive | 144 (12·3) | 82 (56·9) | 1·1 (0·8–1·6) | 0·481 | ||

| Negative | 1022 (87·7) | 550 (53·8) | Reference | |||

| Smoking | 1518 (65·7) | |||||

| Yes | 434 (28·6) | 237 (54·6) | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 0·949 | ||

| No | 1084 (71·4) | 590 (54·4) | Reference | |||

| Substance abuse (excluding alcohol) | 1401 (60·7) | |||||

| Yes | 140 (10·0) | 84 (60·0) | 1·3 (0·9–1·8) | 0·172 | ||

| No | 1261 (90·0) | 680 (53·9) | Reference | |||

| Substance abuse (including alcohol) | 1474 (63·8) | |||||

| Yes | 460 (31·2) | 250 (54·3) | 1·0 (0·8–1·3) | 0·858 | ||

| No | 1014 (68·8) | 546 (53·8) | Reference | |||

| Lineage | 2309 (100) | |||||

| Lineage 1 | 38 (1·7) | 7 (18·4) | 0·2 (0·08–0·4) | <0·001 | 0·13 (0·05–0·36) | <0·001 |

| Lineage 2 | 65 (2·8) | 43 (66·2) | 1·5 (0·9–2·5) | 0·126 | 1·5 (0·9–2·5) | 0·155 |

| Lineage 3 | 26 (1·1) | 4 (15·4) | 0·1 (0·05–0·4) | <0·001 | 0·15 (0·05–0·45) | 0·001 |

| Lineage 4 | 1741 (75·4) | 984 (56·5) | Reference | |||

| Lineage 5 | 289 (12·5) | 143 (49·5) | 0·8 (0·6–1·0) | 0·026 | 0·7 (0·6–0·9) | 0·032 |

| Lineage 6 | 150 (6·5) | 48 (32·0) | 0·4 (0·3–0·5) | <0·001 | 0·3 (0·2–0·5) | <0·001 |

| Lineage 4 sub-lineage | ||||||

| Cameroon | 1046 (60·1) | 616 (58·9) | Reference | |||

| Ghana | 376 (21·6) | 206 (54·8) | 0·8 (0·7–1·1) | 0·167 | ||

| Haarlem | 156 (9·0) | 91(58·3) | 1·0 (0·7–1·4) | 0·895 | ||

| LAM | 50 (2·9) | 25 (50·0) | 0·7 (0·4–1·2) | 0·215 | ||

| Uganda | 40 (2·3) | 16 (40·0) | 0·5 (0·2–0·9) | 0·02 | ||

| Other | 51 (2·9) | 26 (51·0) | 0·7 (0·4–1·3) | 0·265 | ||

| Not determined | 22 (1·3) | 4 (18·2) | 0·2 (0·1–0·5) | 0·001 | ||

| Drug resistance | 2300 (99·6) | |||||

| Any | 313 (13·6) | 138 (44·1) | 0·6 (0·5–0·8) | <0·001 | 0·7 (0·5–0·9) | 0·002 |

| None | 1987 (86·4) | 1090 (54·9) | Reference | |||

| Isoniazid mono-resistant | 2300 (99·6) | |||||

| Yes | 295 (12·8) | 129 (43·7) | 0·6 (0·5–0·8) | <0·001 | ||

| No | 2005 (87·2) | 1099 (54·8) | Reference | |||

| Multidrug resistant (MDR) | 2300 (99·6) | |||||

| Yes | 81 (3·5) | 35 (43·2) | 0·7 (0·4–1·0) | 0·063 | ||

| No | 2219 (96·5) | 1193 (53·8) | Reference | |||

| Cluster size (n) | 1227 (53·1) | |||||

| Small (2) | 290 (23·6) | |||||

| Medium (3–5) | 262 (21·4) | |||||

| Large (6–20) | 452 (36·8) | |||||

| Very large (>20) | 223 (18·2) | |||||

MTBC, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex; TB, tuberculosis; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; JHS, junior high school; GH, Ghanaian cedi.

For the multivariate model, only variables with p < 0.1 and with at least 90% of available data were included. However ‘locality’ was excluded due to the small sample size from the rural setting. Residence classification, marital status, isoniazid mono-resistance, and MDR were excluded due to collinearity with other variables in the model.

A cluster was defined as two or more isolates (same strain) that share an indistinguishable spoligotype and 15-locus MIRU-VNTR allelic pattern, but allowing for one missing allelic data at any one of the difficult-to-amplify MIRU loci.

A significant decreasing trend in the probability of belonging to a clustered case was found with increasing age category (p = 0.004).

Table 5.

Risk factors associated with TB clustering: logistic regression analysis stratified by lineage.a

| Variables | Lineage 4 (n = 1741) |

Univariate | Multivariateb |

Lineage 5 (n = 289) |

Univariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB cases, n (%) | Clustered casesc, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | TB cases, n (%) | Clustered casesc, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Year diagnosed | 1741 (100) | 289 (100) | |||||||

| 2012 | 183 (10·5) | 120 (65·6) | 1·5 (1·1–2·1)* | 1·4 (1·0–2·1) | 0·062 | 26 (9·0) | 14 (53·8) | 1·2 (0·5–2·9) | 0·659 |

| 2013 | 568 (32·6) | 318 (56·0) | Reference | 98 (33·9) | 48 (49·0) | Reference | |||

| 2014 | 548 (31·5) | 300 (54·7) | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 1·0 (0·7–1·3) | 0·847 | 92 (31·8) | 43 (46·7) | 0·9 (0·5–1·6) | 0·757 |

| 2015 | 442 (25·4) | 244 (55·2) | 1·0 (0·8–1·2) | 1·0 (0·7–1·3) | 0·955 | 73 (25·3) | 38 (52·1) | 1·2 (0·6–2·1) | 0·691 |

| Age (years) | 1672 | 283 | |||||||

| <15 | 27 (1·6) | 20 (74·1) | 2·1 (0·9–5·0) | 5 (1·8) | 3 (60·0) | ||||

| 15–29 | 497 (29·7) | 289 (58·2) | Reference | 78 (27·6) | 42 (53·8) | ||||

| 30–39 | 432 (25·8) | 252 (58·3) | 1·0 (0·8–1·3) | 68 (24·0) | 31 (45·6) | ||||

| 40–59 | 580 (34·7) | 315 (54·3) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 94 (33·2) | 48 (51·1) | ||||

| >59 | 136 (8·1) | 71 (52·2) | 0·8 (0·5–1·2) | 38 (13·4) | 16 (42·1) | ||||

| Locality | 1741 (100) | 289 (100) | |||||||

| Rural | 153 (8·8) | 59 (38·6) | Reference | 15 (5·2) | 4 (26·7) | Reference | |||

| Urban | 1588 (91·2) | 923 (58·1) | 2·2 (1·6–3·1)** | 274 (94·8) | 139 (50·7) | 2·8 (0·9–9·1) | 0·081 | ||

| Residential district | 1165 | 189 | |||||||

| Ablekuma | 412 (35·4) | 237 (57·5) | Reference | 77 (40·7) | 39 (50·7) | Reference | |||

| Ashiedu Keteke | 132 (11·3) | 81 (61·4) | 1·2 (0·8–1·8) | 13 (6·9) | 5 (38·5) | 0·6 (0·2–2·0) | 0·419 | ||

| Ayawaso | 178 (15·3) | 111 (62·4) | 1·2 (0·8–1·8) | 21 (11·1) | 7 (33·3) | 0·5 (0·2–1·4) | 0·163 | ||

| Kpeshie | 166 (14·2) | 88 (53·0) | 0·8 (0·6–1·2) | 37 (19·6) | 25 (67·6) | 2·0 (0·9–4·6) | 0·091 | ||

| Mamprusi East | 56 (4·8) | 19 (33·9) | 0·4 (0·2–0·7)* | 4 (2·1) | 1 (25·0) | 0·32 (0·03–3·26) | 0·339 | ||

| Okaikoi | 134 (11·5) | 80 (59·7) | 1·1 (0·7–1·6) | 24 (12·7) | 12 (50·0) | 1·0 (0·4–2·4) | 0·956 | ||

| Osu Klottey | 87 (7·5) | 58 (66·7) | 1·5 (0·9–2·4) | 13 (6·9) | 5 (38·5) | 0·6 (0·2–2·0) | 0·419 | ||

| Monthly income (GH) | 1222 | ||||||||

| None | 275 (22·5) | 167 (60·7) | Reference | ||||||

| <301 | 605 (49·5) | 351 (58·0) | 0·9 (0·7–1·2) | ||||||

| 301–1000 | 314 (25·7) | 184 (58·6) | 0·9 (0·7–1·3) | ||||||

| >1000 | 28 (2·3) | 11 (39·3) | 0·4 (0·2–0·9)* | ||||||

| Marital status | 1322 | ||||||||

| Single | 591 (44·7) | 355 (60·1) | Reference | ||||||

| Married | 549 (41·5) | 312 (56·8) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·9 (0·7–1·2) | 0·589 | ||||

| Divorced | 124 (9·4) | 78 (62·9) | 1·1 (0·8–1·7) | 1·1 (0·7–1·7) | 0·543 | ||||

| Widowed | 58 (4·4) | 24 (41·4) | 0·5 (0·3–0·8)* | 0·5 (0·3–0·8) | 0·011 | ||||

| Lineage 4 sub-lineage | |||||||||

| Cameroon | 1046 (60·1) | 614 (58·7) | |||||||

| Ghana | 376 (21·6) | 206 (54·8) | 0·9 (0·7–1·1) | 0·9 (0·7–1·2) | 0·403 | ||||

| Haarlem | 156 (9·0) | 91 (58·3) | 1·0 (0·7–1·4) | 1·0 (0·7–1·5) | 0·87 | ||||

| LAM | 50 (2·9) | 25 (50·0) | 0·7 (0·4–1·2) | 0·7 (0·4–1·4) | 0·354 | ||||

| Uganda | 40 (2·3) | 16 (40·0) | 0·5 (0·2–0·9)* | 0·4 (0·2–0·8) | 0·013 | ||||

| Other | 51 (2·9) | 26 (51·0) | 0·7 (0·4–1·3) | 0·8 (0·4–1·6) | 0·558 | ||||

| Not determined | 22 (1·3) | 4 (18·2) | 0·2 (0·1–0·5)* | 0·10 (0·03–0·35) | <0·001 | ||||

| Drug resistance | 1736 | ||||||||

| Any | 241 (13·9) | 114 (47·3) | 0·7 (0·5–0·9)* | 0·7 (0·5–1·0) | 0·059 | ||||

| None | 1495 (86·1) | 867 (58·0) | Reference | ||||||

TB, tuberculosis; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GH, Ghanaian cedi.

Only variables with p < 0.1 from the general logistic regression model in Table 4 were included in this analysis. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

For the multivariate model, only variables with p < 0.1 and with at least 90% of available data were included.

A cluster was defined as two or more isolates (same strain) that share an indistinguishable spoligotype and 15-locus MIRU-VNTR allelic pattern, but allowing for one missing allelic data at any one of the difficult-to-amplify MIRU loci.

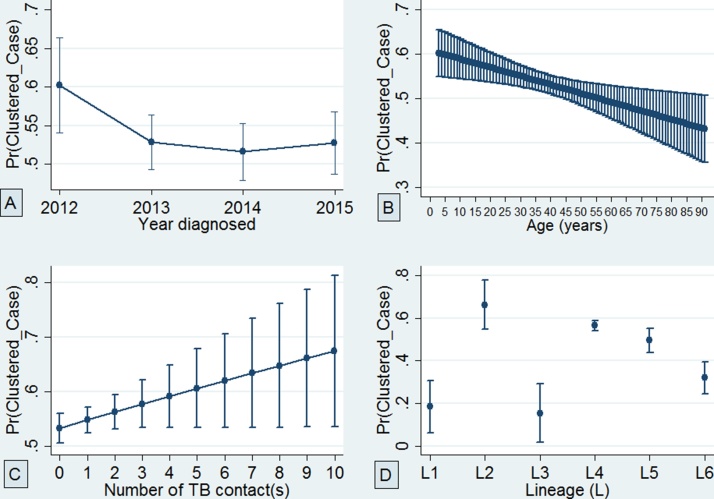

Finally, using adjusted predictions, it was found that the probability of belonging to a clustered case decreased with age and increased with the number of TB contacts (Figure 5). In a separate logistic regression analysis, including age as a continuous variable with belonging to a clustered case as the outcome variable, it was found that each year increase in age was significantly associated with an approximately 1% (95% CI 0.13–2.00%) decrease in the odds of a TB patient being part of a recent transmission event (p = 0.007).

Figure 5.

Adjusted predictions of the probability of belonging to a clustered case with 95% confidence interval: (A) at the year of diagnosis, (B) while ageing, (C) considering the number of close TB contact(s), and (D) considering the number of circulating Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) lineages.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to conduct a population-based prospective molecular epidemiological study to analyze the transmission dynamics of MTBC strains circulating in Ghana and to identify risk factors associated with recent TB transmission.

A high MTBC isolate recovery rate of 78.8% was obtained, higher than that reported in similar studies (Hamblion et al., 2016, Mears et al., 2015) and this strengthens the power of the sample size to make assessments of the TB transmission rate in Ghana. This study identified a high TB clustering (recent TB transmission) rate of 41.2%, which is quite alarming, with the urban and rural areas having estimated rates of 41.7% and 9.0%, respectively (Table 2b). These findings call for intensifying community outreach programs to encourage early case reporting and infection control. Moreover, the analysis predicted the probability of clustering to generally increase with the increase in the number of TB contacts (Figure 5). This means that a susceptible individual is likely to have TB and be involved in a recently transmitted event as the number of TB contacts increases.

Table 2b.

Clustering analysis stratified by study setting and lineages/major sub-lineage populations of MTBC.

| Lineage | Isolates (n) |

Clustered cases (c) |

Clustered strains (nc) |

Single cases (s) |

Total strain types (s + c) |

Clustering ratea (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | |

| Lineage 1 | 34 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 27 | 4 | 30 | 4 | 11.8 | 0 |

| Lineage 2 | 51 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 33 | 4 | 18 | 10 | 23 | 11 | 54.9 | 21.4 |

| Lineage 3 | 25 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 21 | 1 | 23 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| Lineage 4 | 1588 | 153 | 183 | 10 | 907 | 25 | 681 | 128 | 864 | 138 | 45.6 | 9.8 |

| Cameroonb | 969 | 77 | 112 | 5 | 575 | 10 | 394 | 67 | 506 | 72 | 47.8 | 6.5 |

| Ghanab | 326 | 50 | 32 | 4 | 182 | 12 | 144 | 38 | 176 | 42 | 46 | 16 |

| Haarlemb | 144 | 12 | 20 | 1 | 81 | 3 | 63 | 9 | 83 | 10 | 42.4 | 16.7 |

| LAMb | 43 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 18 | 7 | 24 | 7 | 44.2 | 0 |

| Ugandab | 39 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 23 | 1 | 28 | 1 | 28.2 | 0 |

| Lineage 5 | 274 | 15 | 49 | 0 | 137 | 0 | 137 | 15 | 186 | 15 | 32.1 | 0 |

| Lineage 6 | 136 | 14 | 10 | 0 | 43 | 0 | 93 | 14 | 103 | 14 | 24.3 | 0 |

| Summaryc | 2108 | 201 | 252 | 11 | 1131 | 29 | 977 | 172 | 1229 | 183 | 41.7 | 9 |

MTBC, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

The clustering rate was used to estimate the recent transmission rate.

Major lineage 4 sub-population.

The summary was calculated using only the items in cells corresponding to the six main lineages.

Within the study population, no association of recent TB transmission was found with education status, occupation, income level, ethnicity, religion, or HIV status. However, it was observed that individuals below the age of 30 years were associated with recent TB transmission, and this is similar to observations made elsewhere (Hamblion et al., 2016, Vluggen et al., 2017). Also in this study, it was observed that each year increase in age was associated with an approximately 1% (95% CI 0.13–2.00; p = 0.007) decrease in the odds of a TB patient being part of a recent transmission event, implying that compared to younger individuals, older individuals are more likely to get active TB disease by reactivation of latent TB infection rather than through a recent transmission event (Hamblion et al., 2016). This finding puts age as a risk factor for recent TB transmission in Ghana. However, this finding was largely driven by L4 and L5, since separate analysis was not valid for L6 due to the small sample size. Furthermore, it was found that the male-to-female ratio among very large clusters was significantly higher than that observed in the general TB patient population (p = 0.022). This finding, together with the observation that some large clusters involved only male subjects, also indicates that males have a higher risk of recent TB transmission compared to females, suggesting that males may engage in certain social activities that predispose them to belonging to a recent transmission event.

A lower rate of multidrug-resistant TB was seen among large clustered cases compared to the general population (2% vs. 4%, p = 0.031), indicating a low multidrug-resistant TB transmissibility within the study population. This finding further suggests that the majority of drug-resistant TB cases in Ghana acquired the drug resistance during treatment, which indicates poor patient compliance (Danso et al., 2015). Moreover, it was also found that compared to drug (isoniazid and/or rifampicin)-sensitive MTBC strains, it was unlikely to find MTBC strains with isoniazid and/or rifampicin resistance involved in a recent transmission event (adjusted OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.5–0.9).

Within the study setting, a reduced transmission of MAF (L5: 31.8%, L6: 24.7%) compared to MTBss L4 (44.9%) was observed. The high recent transmission rate observed for L4 was driven by both the Cameroon and Ghana sub-lineages, with no difference in their transmissibility, hence identifying these sub-lineages as very important pathogens. The high recent transmission of the Ghana sub-lineage coupled with recently reported association with drug resistance (Otchere et al., 2016) is of public health importance and hence calls for the national tuberculosis control program to support peripheral diagnostic laboratories with facilities to accurately detect and help control the spread of the Ghana sub-lineage.

The higher recent transmission rate for L4 compared to L5 and L6 may not necessarily imply the outcompeting of L5 and L6 by L4, as their relative proportions remained constant over the entire study period (Figure 2) and also based on previous reports (Yeboah-Manu et al., 2016). Despite the low transmissibility of MAF, the observed stable relative proportion over the entire study period may be because the pathogen has adapted to infecting specific host populations (possibly due to unidentified host genetic or environmental factors peculiar to some West African inhabitants), hence enabling the maintenance of a stable prevalence over time. Using adjusted predictions for the probability of clustering, it was found that MAF L5 may still have the propensity to transmit equally to lineage 4 (Figure 5), not forgetting the confounding effect of a higher diversity in spoligotype pattern of L5 compared to L4 and hence reduced clustering of the former (Asante-Poku et al., 2016). Compared to L4, a significant association of L6 with individuals living in villages was found (OR 6.6, p < 0.05; Supplementary material, Table S2). The low recent TB transmission in the villages coupled with an association of L6 could be the reason why low frequencies of L6 strains were observed within the study setting.

This report could be limited by the possibility of an underestimation of the recent transmission rate resulting from the misclassification of strains as unique if they were actually clustered outside of the restricted geographic sampling site and sampling period. However, measures were taken to address the underestimation of recent TB transmission by recruiting up to 90% of the diagnosed TB cases spanning a 3.5-year period. In addition, the possibility of overestimating recent TB transmission rates is also possible considering that the basis of the clustering analysis was done using combined 15-locus MIRU-VNTR typing and spoligotyping, whereas whole genome sequencing could have offered a better resolution of strains.

Overall, the findings indicate high recent TB transmission, suggesting the occurrence of unsuspected outbreaks. The intensification of community education is recommended to improve early case reporting and infection control.

Funding

This research was funded by a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Fellowship Grant (097134/Z/11/Z) to Dorothy Yeboah-Manu. The funding source had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Ethical approval

The Scientific and Technical Committee and then the Institutional Review Board at NMIMR, University of Ghana (FWA00001824) reviewed and approved the study.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the administrative support of Frank Bonsu, National Tuberculosis Control Program, Ghana, and to the laboratory heads and nurses at various facilities who recruited cases and all study participants. We thank the national service personnel for providing great help in completing the questionnaires and making sputum samples available for laboratory investigations. We thank Vida Yirenkyiwaa Adjei and Portia Abena Morgan of Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research for their assistance with some of the laboratory procedures.

Prince Asare was supported by a West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens (WACCBIP)–World Bank ACE PhD Studentship.

Corresponding Editor: Eskild Petersen, Aarhus, Denmark

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.05.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Allix-Beguec C., Harmsen D., Weniger T., Supply P., Niemann S. Evaluation and strategy for use of MIRU-VNTRplus, a multifunctional database for online analysis of genotyping data and phylogenetic identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(8):2692–2699. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00540-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L.F., Tamne S., Brown T., Watson J.P., Mullarkey C., Zenner D. Transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in the UK: a cross-sectional molecular and epidemiological study of clustering and contact tracing. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(5):406–415. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante-Poku A., Nyaho M.S., Borrell S., Comas I., Gagneux S., Yeboah-Manu D. Evaluation of customised lineage-specific sets of MIRU-VNTR loci for genotyping Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante-Poku A., Otchere I.D., Osei-Wusu S., Sarpong E., Baddoo A., Forson A. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium africanum in Ghana. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:385. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1725-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard M., Albert H., Coetzee G., O’Brien R., Bosman M.E. Rapid molecular screening for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in a high-volume public health laboratory in South Africa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(7):787–792. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1436OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P.F., Cave M.D. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1149–1156. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin Y., Hauck Y., Soler C., Fabre M., Vong R., Dehan C. Significance of the identification in the Horn of Africa of an exceptionally deep branching Mycobacterium tuberculosis clade. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danso E., Addo I.Y., Ampomah I.G. Patients’ compliance with tuberculosis medication in Ghana: evidence from a Periurban community. Adv Public Health. 2015;2015:6. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong B.C., Antonio M., Gagneux S. Mycobacterium africanum–review of an important cause of human tuberculosis in West Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(9):e744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong B.C., Hill P.C., Aiken A., Awine T., Antonio M., Adetifa I.M. Progression to active tuberculosis, but not transmission, varies by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage in The Gambia. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(7):1037–1043. doi: 10.1086/591504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field N., Cohen T., Struelens M.J., Palm D., Cookson B., Glynn J.R. Strengthening the Reporting of Molecular Epidemiology for Infectious Diseases (STROME-ID): an extension of the STROBE statement. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;14(4):341–352. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagneux S., Small P.M. Global phylogeography of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and implications for tuberculosis product development. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(5):328–337. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn J.R., Alghamdi S., Mallard K., McNerney R., Ndlovu R., Munthali L. Changes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotype families over 20 years in a population-based study in Northern Malawi. PLoS One. 2010;5(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn J.R., Vynnycky E., Fine P.E. Influence of sampling on estimates of clustering and recent transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis derived from DNA fingerprinting techniques. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(4):366–371. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. What is molecular epidemiology? Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1(4):407–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-96.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblion E.L., Le Menach A., Anderson L.F., Lalor M.K., Brown T., Abubakar I. Recent TB transmission, clustering and predictors of large clusters in London, 2010-2012: results from first 3 years of universal MIRU-VNTR strain typing. Thorax. 2016;71(8):749–756. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenius G., Koivula T., Ghebremichael S., Hoffner S.E., Norberg R., Svensson E. Evolution and clonal traits of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in Guinea-Bissau. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(12):3872–3878. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3872-3878.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamerbeek J., Schouls L., Kolk A., van Agterveld M., van Soolingen D., Kuijper S. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(4):907–914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.907-914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire H., Dale J.W., McHugh T.D., Butcher P.D., Gillespie S.H., Costetsos A. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in London 1995-7 showing low rate of active transmission. Thorax. 2002;57(7):617–622. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.7.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malm S., Linguissi L.S., Tekwu E.M., Vouvoungui J.C., Kohl T.A., Beckert P. New Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex sublineage, Brazzaville, Congo. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(3):423–429. doi: 10.3201/eid2303.160679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears J., Abubakar I., Cohen T., McHugh T.D., Sonnenberg P. Effect of study design and setting on tuberculosis clustering estimates using Mycobacterial Interspersed Repetitive Units-Variable Number Tandem Repeats (MIRU-VNTR): a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulenga C., Shamputa I.C., Mwakazanga D., Kapata N., Portaels F., Rigouts L. Diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes circulating in Ndola, Zambia. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otchere I.D., Asante-Poku A., Osei-Wusu S., Baddoo A., Sarpong E., Ganiyu A.H. Detection and characterization of drug-resistant conferring genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: a prospective study in two distant regions of Ghana. Tuberculosis. 2016;99:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto J., Wada T., Suzuki Y., Ikeda T., Mizuta K., Yamamoto T. Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission among elderly persons, Yamagata Prefecture, Japan, 2009-2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(3):448–455. doi: 10.3201/eid2303.161571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabbeer A., Cowan L.S., Ozcaglar C., Rastogi N., Vandenberg S.L., Yener B. TB-Lineage: an online tool for classification and analysis of strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12(4):789–797. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supply P., Allix C., Lesjean S., Cardoso-Oelemann M., Rusch-Gerdes S., Willery E. Proposal for standardization of optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(12):4498–4510. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surie D., Fane O., Finlay A., Ogopotse M., Tobias J.L., Click E.S. Molecular, spatial, and field epidemiology suggesting TB transmission in community, not hospital, Gaborone, Botswana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(3):487–490. doi: 10.3201/eid2303.161183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese B., Al-Omari R., Grimshaw C., Al-Hajoj S. Endogenous reactivation followed by exogenous re-infection with drug resistant strains, a new challenge for tuberculosis control in Saudi Arabia. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2013;93(2):246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vluggen C., Soetaert K., Groenen G., Wanlin M., Spitaels M., Arrazola de Onate W. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in Brussels, 2010-2013. PLoS One. 2017;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker T.M., Lalor M.K., Broda A., Saldana Ortega L., Morgan M., Parker L. Assessment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission in Oxfordshire, UK, 2007-12, with whole pathogen genome sequences: an observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(4):285–292. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70027-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 20 ed. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015. Global tuberculosis report 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Global tuberculosis report. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Luo T., Shen X., Wu J., Gan M., Xu P. Transmission of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Shanghai, China: a retrospective observational study using whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;17(3):275–284. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30418-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah-Manu D., Asare P., Asante-Poku A., Otchere I.D., Osei-Wusu S., Danso E. Spatio-temporal distribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains in Ghana. PLoS One. 2016;11(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah-Manu D., Yates M.D., Wilson S.M. Application of a simple multiplex PCR to aid in routine work of the mycobacterium reference laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(11):4166–4168. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.11.4166-4168.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.