Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated the test-retest repeatability of blood flow velocities in the retrobulbar central retinal artery (CRA) and explored whether reduced blood flow is related to the degree of visual function loss in retinitis pigmentosa (RP) patients with wide range of disease severity.

Materials and Methods

We measured CRA peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end diastolic velocity (EDV) to calculate mean flow velocity (MFV) in 18 RP patients using color Doppler imaging with spectral flow Doppler (GE Logiq7 ultrasound) twice in each eye at each of two visits within a month. At each of these two visits, we measured ETDRS visual acuity (VA), quick Contrast Sensitivity Function (qCSF), Goldmann visual fields (GVF), 10–2 Humphrey visual fields (HVF), and dark-adaptation at 5° from fixation with the AdaptDx; multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) was obtained at a single visit.

Results

Mean coefficients of variation for PSV, EDV and MFV were 16.1–19.2% for within-visit measurements and 20.1–22.4% for between-visit measures. Across patients, greater visual function loss assessed with VA (p = 0.04), extinguished versus measurable amplitude in ring 1 for mfERG (p = 0.001), and cone-only versus rod function with the AdaptDx (p = 0.002) were statistically significantly correlated with reduced MFV in the CRA when included a multilevel multivariate regression model along with the qCSF and HVF results, which all together accounted for 47% of the total variance in MFV. GVF log retinal areas (V4e and III4e; p = 0.30 and p = 0.95, respectively) and measurable far peripheral vision during GVF testing (p = 0.66) were not significantly related to MFV.

Conclusions

MFV in the CRA decreased with impaired central vision due to loss of both rod and cone function, had good test-retest repeatability, and may serve as a biomarker outcome to determine the potential physiological basis for improvements in RP clinical trials of therapies with indirect effects on blood flow to the retina.

Keywords: Blood flow, central retinal artery, color Doppler imaging, mean flow velocity, retinitis pigmentosa, visual function

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a group of inherited retinal diseases that present clinically with attenuated retinal vasculature and vision loss due to progressive dysfunction of photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium. It has been hypothesized that anatomical and functional changes in the retinal vessels of RP patients occur secondarily to loss of outer retinal function, possibly due to a hyperoxic state in the inner retina, extracellular matrix thickening, and/or reduced inner retinal metabolic demand due to a decline in trophic factors.1,2 Longitudinal loss of visual field area over a 3-year period has been significantly correlated with a reduction in the diameter of the retinal arteries and veins adjacent to the optic nerve in RP patients.1 Reduced choroidal3,4 and retinal blood flow 5–7 have been documented in either early or advanced stage RP patients compared to normal controls. Laser speckle flowgraphy measures of both retinal and choroidal blood flow signals were also significantly reduced in RP compared to controls and correlated with reduced macular sensitivity during static perimetry in RP.8

In addition to evaluating blood flow within the eye, it is also possible to use ultrasonography (Color Doppler imaging, CDI, with spectral flow doppler) to measure retinal and choroidal blood flow at the blood vessel’s retrobulbar segment outside the eye.9 This methodology has been previously used to describe the hemodynamics of ocular diseases such as glaucoma, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, central retinal artery or vein occlusion, ocular tumors, and ocular ischemic syndrome, as well as to evaluate the effects of ophthalmic surgeries and drugs.9 We have evidence from previous studies using CDI in RP patients that their retrobulbar blood supply may be reduced compared to normal controls, 10,11 with significantly decreased velocities recorded in the ophthalmic artery,11 central retinal artery (CRA),10 and posterior ciliary arteries (PCA)11. However, our search of pubmed and similar databases revealed no previous publications describing the correlation between the severity of visual function loss and retrobulbar blood flow velocity in RP patients. Therefore, it is currently unknown whether blood flow in the retinal vessels is reduced early in RP and remains at a steady, reduced level throughout the disease or if blood flow undergoes gradual further reductions over time as vision loss becomes more advanced. Furthermore, it has not yet been established which aspects of visual function loss might be related to reduced blood flow specifically in the retinal vessels in RP patients.

To help establish the validity of using CDI with spectral flow doppler to determine changes in CRA retrobulbar blood flow among RP patients, it is important to evaluate whether this measurement has acceptable test-retest reliability in this patient population. The between-visit reproducibility of CDI for peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end diastolic velocity (EDV) in the CRA of patients with glaucoma has been reported to be good and relatively similar to non-glaucomatous controls, with mean coefficients of variation (CoV) of 7–28% and 7–19% in glaucoma versus 21% and 7–22% in controls for PSV and EDV, respectively, reported across previous studies.12 The within- and between-visit reliability of these measures has not been previously established for RP patients, in which we consider necessary to help detect and interpret changes related to disease progression or as a response to intervention.

The main aims of this study were to evaluate whether repeated CDI measurements of CRA blood flow in RP patients are reliable and related to visual function loss across individuals at various stages of disease progression. We hypothesized that the use of a specific protocol administered by trained experienced sonographers would yield test-retest CoVs that were similar to previously published CoVs for these measurements in glaucoma patients and normally-sighted controls. In addition, we hypothesized that CRA mean flow velocity (MFV) was reduced in RP patients with more advanced vision loss.

Materials and methods

The protocol for the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Nova Southeastern University and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects after explanation of the nature and possible consequences of the study.

Subjects

Study participants included 18 patients diagnosed with RP. One-third of the subjects (n = 6) were recruited through the clinical optometric practices (i.e., The Eye Care Institute and Lighthouse for the Blind of Broward) affiliated with the Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA. The remaining 12 subjects (67%) received diagnoses of RP from eye care providers outside these practices and self-referred after learning of the study through online listings (e.g., clinicaltrials.gov NCT02086890). Non-smoking persons older than the age 18 were eligible for the study if they had a confirmed diagnosis of RP with better than 20/400 best-corrected vision in at least one eye and greater than 20% loss of Goldmann Visual Field (GVF) area with the III4e test target in at least one eye. Potential subjects were excluded if they had vision loss due to ocular diseases other than RP. Other exclusion criteria included those who had received previous electro-stimulation therapy for RP, cognitive impairment, were non-English speaking, were receiving current psychiatric care, had a history of excessive bleeding, implanted cardiac pacemaker, pregnancy, reduced general health, or were taking steroidal systemic medication. None of the study participants had any changes in their prescription medications or over the counter supplements during the course of the study. None of the included participants’ eyes had cystoid macular edema within the foveal region. The mean age for the 18 participants was 44 years (SD: 12 years; range: 25–70 years), and seven were women (39%). There were nine Caucasians, six Hispanic/Latinos, one African-American, and two Asians.

Study design

Data collection occurred from September 2014 to April 2015. All vision tests were administered by a single examiner (AKB), and all study outcome measures (except for electrophysiology that was performed once) were repeated at two visits (except for one participant who was evaluated twice across three visits). Subjects were scheduled to return for the second visit within a one- to two-week period (mean intervisit time = 12.7 days, range 1–42 days). Each visit lasted approximately 5–6 hours. Subjects were offered a lunch voucher to take a break about 2–4 hours after the start of the visit and after the ultrasound measures of ocular blood flow (OBF) were obtained. At each visit, the tests were obtained in the same order, including the OBF measurements, which were taken at the same time of day, around noon or 12 pm, to remove diurnal fluctuations.

Outcome measures

The same examination room and equipment were used for all participants at each visit to ensure that all visual function test conditions were consistent. Best-corrected visual acuity (VA) was measured in each eye using either the refraction findings in a trial frame or habitual spectacle correction if no significant change in refraction was obtained at baseline. The Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS; Lighthouse International, New York, NY) trans-illuminated three-chart series were used with a three meter test distance that was modified to one meter for severely reduced acuities if fewer than 10 letters were originally identified.

Contrast sensitivity (CS) was measured with two methods at each visit: the Pelli-Robson chart (Metropia, Ltd., Essex, UK), followed by the quick Contrast Sensitivity Function (qCSF) test (Adaptive Sensory Technology; Boston, MA). Pelli-Robson CS was assessed binocularly at one meter, while the qCSF was typically administered in each eye individually at four meters (or at two meters in the case of subjects with severely reduced VA worse than 0.7 logMAR). Six eyes of four participants could not detect any letters during qCSF testing due to severe CS loss and were scored as zero. The qCSF testing was performed with 25 trials per eye (~7–10 minutes) according the previously published methods13 using letters presented on a monitor screen and a Bayesian adaptive algorithm to assess the area under the log CS function (AULCSF) across various spatial frequencies.

Goldman visual field (GVF) kinetic perimetry was obtained in each eye using the V4e and III4e test targets. The GVF areas were plotted by tracing along each of 24 meridians one at a time, moving at a rate of approximately 5°/second, from non-seeing (peripheral) to seeing (central) areas. All meridians were evaluated, and some of the meridians (~20%–25%) were rechecked for consistency in responses. Irregular seeing areas and scotomas were further explored in tangential directions as needed to obtain a reliable contour. Areas that were noted as not consistently seen were not included in our calculations of the GVF area. The tested points were connected with straight lines to form the areas or isopters.

Humphrey visual field (HVF) static automated perimetry was obtained in each eye following GVFs. Subjects who tended to have worse vision (i.e., 0.4 logMAR) were tested with size V4e 10-2 Fastpac, while others (n = 10; 55%) with better vision were evaluated with the III4e 10-2 SITA-Fast, which provides a mean deviation (MD) score used in the analysis. In addition, we calculated the mean sensitivity for the four most central test points located within 2 degrees of the fixation target during HVF testing for all subjects.

We determined whether scotopic sensitivity was mediated by cones only (sensitivity 0–3 log units), or both cones and rods (measurable rod intercept at 3 log units), using the AdaptDx (Maculogix; Hummelstown, PA). The rod intercept is defined as the amount of time required for sensitivity recovery to reach a criterion sensitivity level of 5 × 10−3 scot cd/m2, which occurs at 3 log units below the brightest stimulus that is presented by the AdaptDx. We administered this test with a 76% initial flash for bleaching and evaluated the most sensitive retinal area located at 5 degrees from fixation either superiorly, inferiorly, nasally or temporally as was determined by the HVF results.

Multifocal electroretinograms (mfERG) were obtained in each eye using Burian-Allen electrodes and the Veris system (Electro-Diagnostic Imaging, Inc.; Redwood, CA) at only one of the study visits. For the majority of the subjects (n = 17; 81%), the mfERG was obtained at the second visit. The P1 response amplitude for ring 1 was only measurable (i.e., ≥3.5 nV/deg2) in seven participants (39%), whereas the others did not have a measurable response; therefore, we compared the RBF results for those who did versus did not have a measurable mfERG P1 amplitude in ring 1.

Retrobulbar ocular hemodynamics were measured with CDI and spectral flow doppler using the same instrument (GE Logiq 7) and transducer probe across all visits and patients according to previously published guidelines for this procedure.14 We used the M12L linear array transducer probe broad bandwidth with frequencies from 12–15 Hz on the small parts setting. After the patient was lying down for at minimum of 5 minutes, two measurements of each eye’s CRA were obtained in primary gaze at each of the two baseline visits (total of four measures per eye) by one of three trained sonographers. The scans were always performed on the right eye followed by the left eye and repeated. To obtain the measurements in primary gaze, the study sonographers provided feedback on eye positioning to the participants and/or they were able to open the fellow eye that was not being measured to maintain fixation on an overhead spot/light on the ceiling. The study sonographers were careful not to apply significant pressure to the eye with the measurement probe oriented perpendicularly to the eye (i.e., without tilting or rocking) in order to limit possible effects on blood flow. Participants were instructed to immediately report any sensation of ocular pressure during the measurements. The study sonographers were trained to measure the same location of the CRA across patients, and the room temperature was maintained consistently within 5 degrees Fahrenheit across visits. The same sonographer performed both visits of each participant for the majority of our subjects (n = 11; 61%) and placed markers at the time of the measurement to quantify the peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end diastolic velocity (EDV) in the CRA. The mean PSV and mean EDV across the two visits were used to calculate mean flow velocity (MFV) using the equation: MFV=((PSV)+(2 EDV))/3.15 Blood pressure and pulse rate were measured three times at each visit immediately following the CDI measurements and were taken, while the subject was still fully reclined. These measures were used to calculate pulse pressure (PP = mean systolic blood pressure –mean diastolic blood pressure) and mean arterial pressure (MAP = ((mean systolic blood pressure)+(2 * mean diastolic blood pressure))/3).

Data analysis

We used dedicated computer software to digitize the GVF maps and to calculate the seeing log retinal areas for each eye.16 The total GVF area included the central area, as well as any isolated peripheral islands, minus any scotomatous areas. We present GVF areas on a logarithmic scale because it has been documented in several longitudinal, natural history studies that the remaining viable retinal area declines over time according to a negative exponential function.17

We determined CoV and 95% coefficients of repeatability for PSV, EDV and MFV computed individually for each subject using the test–retest difference of the OBF measures obtained within- and between-visits. For the between-visit test-retest data, we found an increase in variability of the differences as the magnitude of the measurement increased (i.e., heteroscedasticity); therefore, we calculated the percent difference [(Visit1-Visit2)/Average] to use in a Bland-Altman plot analysis rather than the differences.

Correlations of OBF (i.e., PSV, EDV and MFV) with visual function were adjusted for age and gender and analyzed using multilevel linear regression models to account for correlations between a subject’s eyes18 using Stata/IC version 13.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).<Please check the clarity of the phrase “19o been shown” in the sentence “We adjusted for gender and age … CRA of glaucoma patients.”> We adjusted for gender and age since it was recently published that there are observable sex-related differences in the retinal blood flow of normals,19o been shown to have a small effect on blood flow in the CRA of glaucoma patients.20 In young, healthy normals, a slight but significant increase in CRA blood flow occurred among those with greater MAP,21 which was not found in our RP data (−0.02; 95% CI: −0.06, 0.01; p = 0.19); therefore, we did not adjust for MAP in our analyses. MFV and EDV were both normally-distributed variables as per Shapiro–Wilk analysis; however, PSV was not normally-distributed, and therefore, we performed a log-transformation of this variable to use for the analysis.

Results

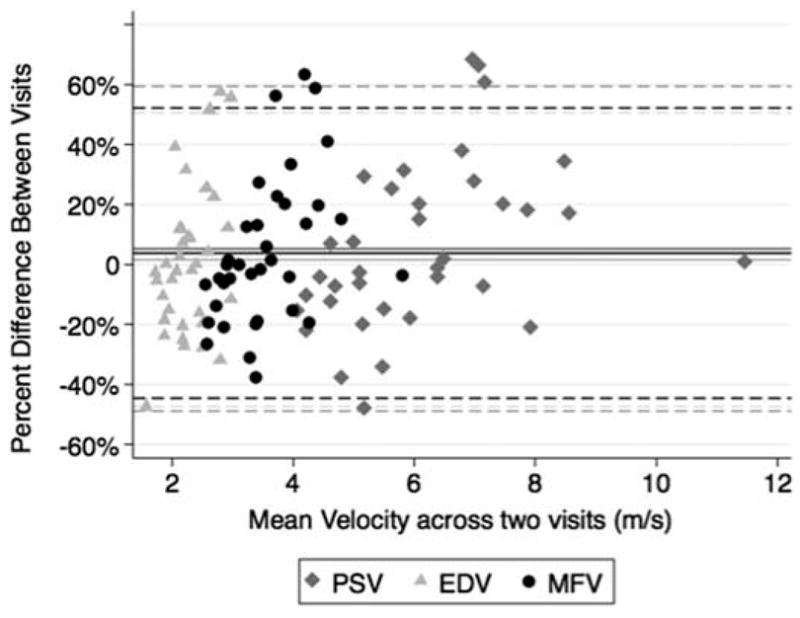

Table 1 displays the mean within-visit and between-visit CoV and 95% coefficients of repeatability for MFV, PSV and EDV. The mean CoVs ranged from 16.1% to 22.4% for within- and between-visit variability in MFV, PSV and EDV, with mean CoV values for these measures that were under 20% for within-visit variability and slightly above 20% for mean between-visit variation. Figure 1 shows a Bland-Altman plot for the mean between-visit test–retest differences in PSV, EDV, and MFV. The mean difference is close to zero for PSV, EDV and MFV; that is, 5.2%, 1.6%, and 3.8%, respectively. This amount of bias is not significant, since the line of equality (i.e., zero difference) is within the 95% confidence intervals for the mean difference, which is from −49% to 59% for PSV, from −47% to 51% for EDV, and from −45% to 52% for MFV. Therefore, there was not a tendency to obtain a greater velocity measurement at the second visit.

Table 1.

Reliability indices for the CRA blood flow measures.

| Coefficients of Variation

|

95% Coefficients of Repeatability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) | SD (%) | ||

| MFV within-visit | 18.4 | 24.3 | 1.21 m/s |

| MFV between-visit | 20.1 | 18.0 | 1.42 m/s |

| PSV within-visit | 16.1 | 9.9 | 1.75 m/s |

| PSV between-visit | 22.4 | 18.7 | 2.02 m/s |

| EDV within-visit | 19.2 | 14.2 | 0.73 m/s |

| EDV between-visit | 20.4 | 16.4 | 0.70 m/s |

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman graph of the mean test–retest percent difference between-visits plotted against the mean velocities obtained for PSV, EDV and MFV in each eye. The mean differences are shown as solid lines, and the 95% limits of agreement are shown with dashed lines.

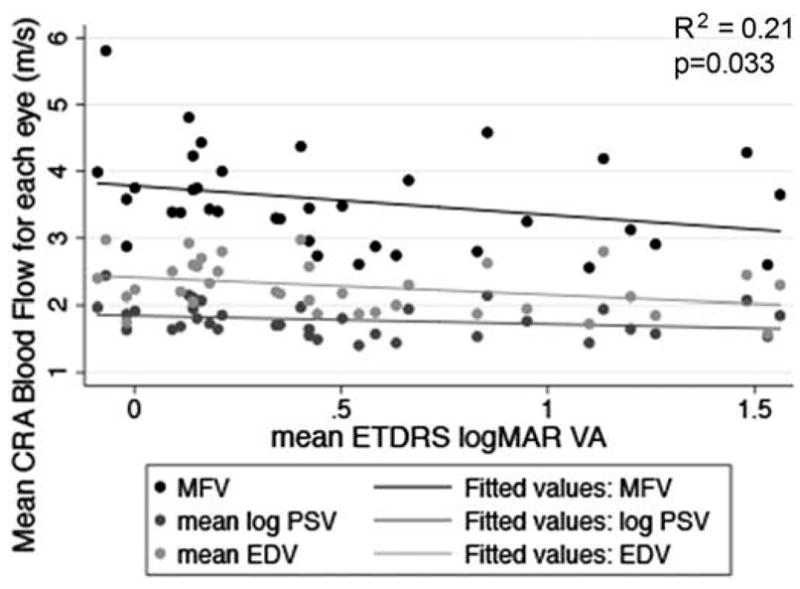

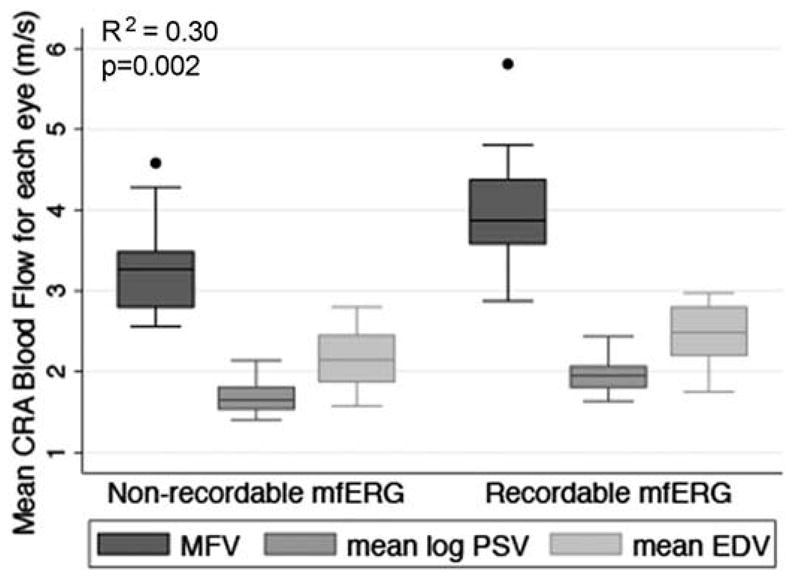

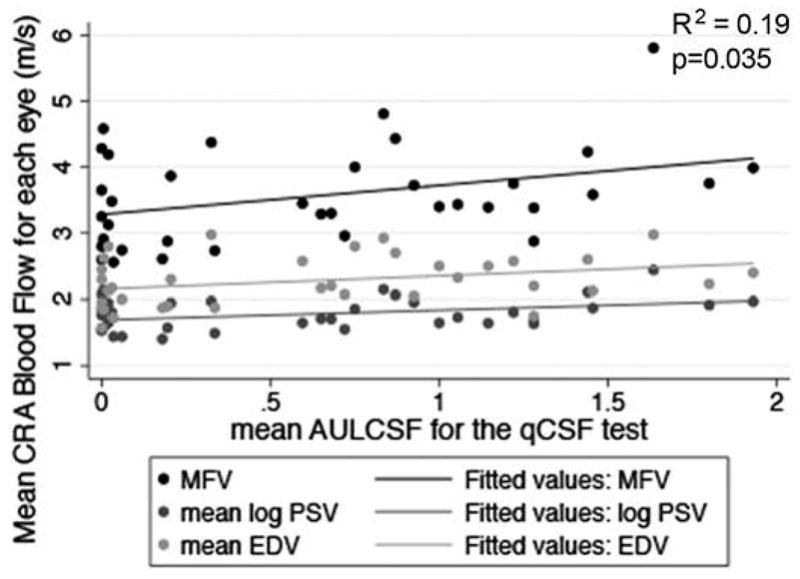

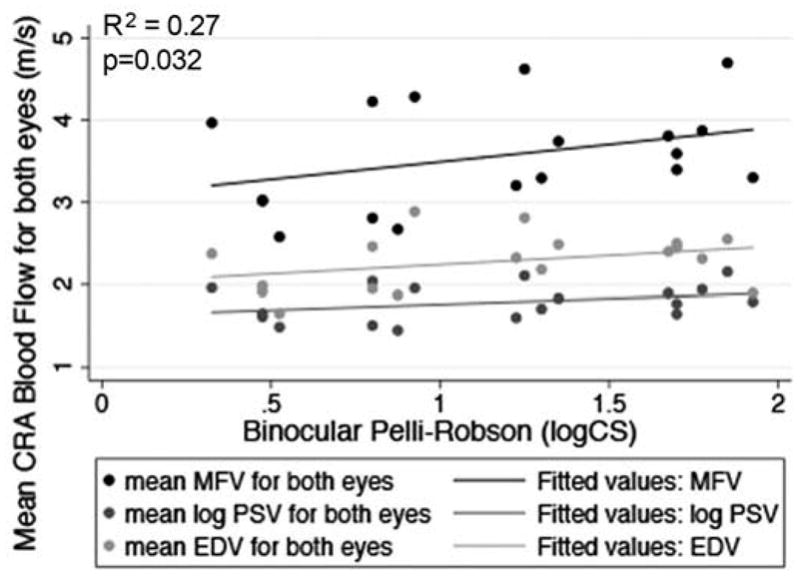

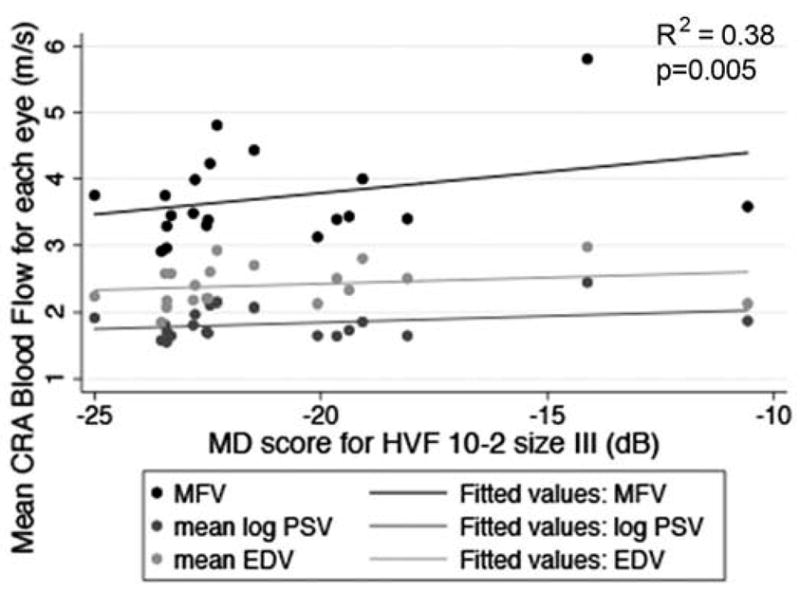

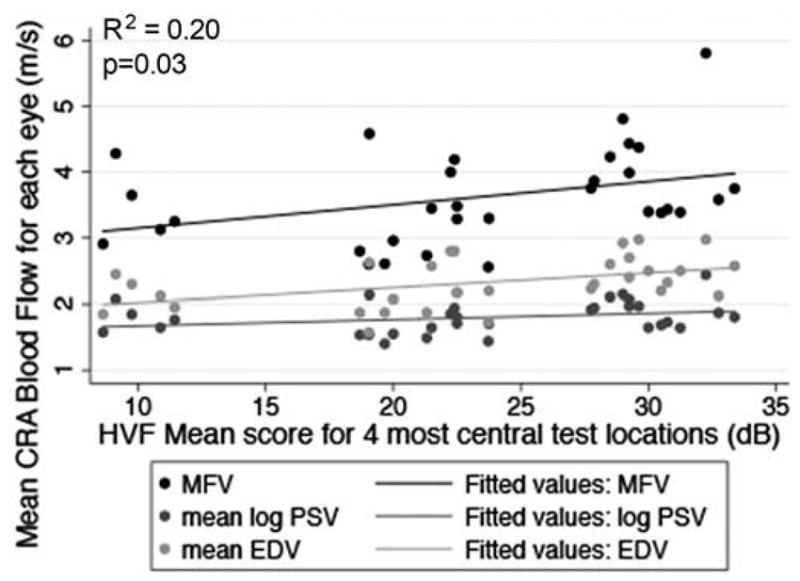

Table 2 indicates the CRA blood flow and visual function characteristics for the study population. Table 3 displays the data for the relationships between the mean OBF measures (i.e., MFV, PSV and EDV) and each of the visual function measures, after adjusting for age and gender. Figures 2–7 provide a graphical depiction of these data, indicating significant correlations between in reductions in MFV and visual function measures of VA, qCSF, Pelli-Robson CS, HVF and mfERG ring 1. For every 1.0 log unit decrease in mean VA, there was a significant 0.57 m/s reduction in MFV on average (R2 = 0.21; p = 0.03). For every 1.0 log unit decrease in mean AULCSF measured with the qCSF test, there was a significant 0.44 m/s reduction in MFV on average (R2 = 0.19; p = 0.04). For every 1.0 log unit decrease in mean binocular Pelli-Robson CS, there was a significant 0.54 m/s reduction in MFV in the CRAs of both eyes averaged (R2 = 0.27; p = 0.03). For every 1.0 dB reduction in mean sensitivity at the four most central test locations around fixation during the HVF test, there was a significant 0.04 m/s reduction in MFV on average (R2 = 0.20; p = 0.03). In a subgroup analysis of patients who had better vision and completed HVF testing with the size III target, MFV was significantly reduced by 0.12 m/s for every 1.0 dB reduction in HVF 10-2 mean deviation scores (R2 = 0.38; p = 0.005). On average, reduced MFV was not significantly related to GVF log retinal areas measured with the V4e and III4e test targets (p = 0.30 and p = 0.95; respectively). We also considered whether MFV was different among subjects who still had remaining far peripheral vision measured with the GVF (n = 8; 44%) versus those who had lost their far peripheral visual field, and found no significant difference in MFV between those groups after adjusting for age and gender (p = 0.66). Only three of the subjects had a measurable rod intercept within 10 minutes of testing with the AdaptDx, and on average, they did not have a significant difference in MFV when compared to participants with only cone function measured with the AdaptDx in a crude analysis adjusted only for age and gender (p = 0.13). Subjects who had a measurable mfERG amplitude in ring 1 had MFV that was significantly greater by 0.72 m/s on average (R2 = 0.30; p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Mean blood flow and visual function characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristics | Mean | Range | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFV | 3.56 m/s | (2.56,5.81) | 0.72 |

| PSV | 6.13 m/s | (4.08,11.48) | 1.54 |

| EDV | 2.28 m/s | (1.58,2.98) | 0.38 |

| logMAR ETDRS VA | 0.52 | (−0.09,1.56) | 0.49 |

| qCSF AULCSF | 0.63 | (0.00,1.93) | 0.60 |

| Pelli-Robson log CS | 1.16 | (0.33,1.93) | 0.53 |

| HVF 10-2 MD size III | −21.00 dB | (−25.0,−10.58) | 3.51 |

| HVF 4 central points | 23.33 dB | (8.63,33.38) | 7.15 |

| GVF III4e log area | 1.21 mm2 | (−0.54,2.74) | 0.83 |

| GVF V4e log area | 1.70 mm2 | (0.29,2.83) | 0.73 |

| Duration of VF loss | 23.44 years | (4,42) | 13.63 |

| Duration of night loss | 29.11 years | (3,65) | 16.80 |

Table 3.

MFV, mean log PSV or mean EDV in the CRA according to each measure of visual function across RP patients (i.e., individual correlations adjusted for age and gender).

| Visual Functiond | log PSV | EDV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Coef. | (95% CI) p-value | Coef. | (95% CI) p-value | Coef. | (95% CI) p-value | |

| logMAR ETDRS VAa | −0.57 | (−0.05,−1.10) 0.033* | −0.17 | (−0.35,−0.0003) 0.05* | −0.31 | (−0.59,−0.02) 0.034* |

| qCSF AULCSFa | 0.44 | (0.03,0.85) 0.035* | 0.14 | (0.01,0.28) 0.034* | 0.23 | (−0.006,0.46) 0.057 |

| Pelli-Robson log CSa | 0.54 | (0.05,1.04) 0.032* | 0.19 | (0.03,0.35) 0.020* | 0.24 | (−0.04,0.53) 0.09 |

| HVF 10-2 MD size IIIb | 0.12 | (0.04,0.21) 0.005* | 0.04 | (0.02,0.07) 0.002* | 0.03 | (−0.01,0.07) 0.18 |

| HVF 4 central pointsb | 0.04 | (0.004,0.08) 0.03* | 0.01 | (−0.002,0.02) 0.09 | 0.02 | (0.005,0.04) 0.012* |

| GVF III4e log areaa | 0.01 | (−0.33,0.36) 0.95 | 0.02 | (−0.09,0.13) 0.73 | −0.03 | (−0.22,0.16) 0.75 |

| GVF V4e log areaa | −0.20 | (−0.57,0.17) 0.30 | −0.05 | (−0.18,0.07) 0.39 | −0.12 | (−0.32,0.08) 0.25 |

| AdaptDx rod function | 0.59 | (−0.18,1.35) 0.13 | 0.22 | (−0.02,0.47) 0.07 | 0.11 | (−0.33,0.55) 0.64 |

| Duration of VF lossc | −0.19 | (−0.39,0.01) 0.06 | −0.07 | (−0.14,−0.01) 0.024* | −0.06 | (−0.18,0.05) 0.28 |

| Duration of night lossc | −0.14 | (−0.33,0.06) 0.17 | −0.05 | (−0.11,0.01) 0.12 | −0.05 | (−0.16,0.06) 0.36 |

| measurable mfERG | 0.72 | (0.39,2.20) 0.002* | 0.25 | (0.10,0.40) 0.001* | 0.31 | (0.03,0.58) 0.030* |

Statistically significant (p < 0.05).

for every 1 log unit increase.

for every 1 dB increase.

for every 10 year increase.

All visual function variables are adjusted for age and gender.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of MFV, mean log PSV and mean EDV in the CRA in relation to mean logMAR ETDRS VA in each eye. The drawn lines represent linear regression lines. The R2 value and p-value are for the relationship between MFV and VA adjusted for age and gender.

Figure 7.

Box plot of MFV, mean log PSV, and mean EDV in the CRA of each eye according to patients who had or did not have a recordable mfERG for ring 1. The bottom and top of the box are the 25th and 75th percentile (i.e., the upper and lower quartiles, respectively), and the band near the middle of the box is the 50th percentile (i.e., the median). The ends of the whiskers represent the lowest datum within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the lower quartile, and the highest datum still within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the upper quartile. Any data not included between the whiskers are plotted as an outlier indicated by a dot. The R2 value and p-value are for the relationship between MFV and recordable mfERG for ring 1 adjusted for age and gender.

In a multivariate regression including all visual function variables listed in Table 1 that had a p-value < 0.15 for the individual linear regressions with MFV, 47% of the total variance of MFV was explained. In this multivariate regression model, we found that the following visual function measures were statistically significantly reduced in relation to decreased MFV after adjusting for age and gender: VA (−1.15; 95% CI: −2.24, −0.05; p = 0.04), measurable response in ring 1 for mfERG (1.11; 95% CI: 0.43, 1.79; p = 0.001), and rod function measured with the AdaptDx (1.20; 95% CI: 0.44, 1.96; p = 0.002).

Reductions in both log PSV and EDV on average were statistically significantly associated with decreased VA (p = 0.05 and p = 0.03, respectively) and those who did not have a measurable response in ring 1 of the mfERG test (p = 0.03). Reduced log PSV on average was significantly related to reduced qCSF AULCSF (p = 0.03), Pelli-Robson CS (p = 0.02), HVF mean deviation score (p = 0.002), and increased self-reported duration of visual field loss (p = 0.02), but these measures were not significantly associated with EDV. Reduced EDV on average was significantly correlated with the mean sensitivity of the four most central points around fixation during HVF 10-2 testing, which was not significantly associated with log PSV on average (p = 0.13).

Discussion

The good repeatability of the OBF results within- and between-visits in this study supports the utility of CDI ultrasonography to assess and monitor for changes in CRA retro-bulbar blood flow in RP patients. The test–retest reliability in RP is comparable to other studies that have examined the CoV for blood flow in the CRA as measured by CDI ultrasonography in normally-sighted controls and glaucoma patients.12 The validity of these CRA blood flow measures in RP is further supported by our evidence that reduced MFV was related to decreased central vision loss, as well as a previous study’s finding that the CRA blood flow is significantly reduced in RP compared to normal controls 10 Furthermore, we found that MFV in the CRA was significantly correlated with several different aspects of central visual function involving subjective responses mediated by cone photoreceptors (i.e., VA, CS) or rod photoreceptors (i.e., measurable rod intercept during dark-adaptation), as well as an objective measure of cone and bipolar cell function (i.e., mfERG).

In RP, it is possible to have reduced central vision and mid-peripheral visual field loss along with maintained temporal, far peripheral visual fields, or to have very good central vision with extremely constricted visual fields (i.e., without any temporal, far peripheral remaining islands of vision).22 In our cohort, for the majority and mid-range of GVF log retinal area results, there was a wide range of central vision loss, such that subjects with minimal VA loss (i.e., better than 0.3 logMAR) had similar GVF log retinal area to those with more substantial VA loss. The same relationship and this finding were also evident for the other following central visual function tests when compared to the GVFs: qCSF, the mean sensitivity for the four most central points during the HVF 10-2, and for whether there were recordable results for ring 1 during mfERG. Therefore, given the lack of a strong correlation between GVFs and the central vision measures, it was not entirely unexpected that we did not find a significant relationship between MFV and GVFs, as was elucidated for MFV and the central vision measures.

In normal eyes without RP, the blood flow in the retinal vessels to the temporal side toward the metabolically demanding macula is significantly greater than to the nasal side of the optic disc supplying the nasal periphery,23,24 which indicates the CRA circulation primarily feeds the macula where the vessel diameter is greater than in the periphery. Since the majority of the CRA blood flow supplies the macula, it may be hypothesized that reduced retrobulbar MFV in the CRA would not be correlated with far peripheral vision loss measured by GVFs. Furthermore, rod photoreceptor loss in animal models of RP leads to increased reactive oxidative species (ROS) and oxidative stress, which was confirmed in humans by oxidative stress analysis of the aqueous in RP patients.24 Decreased retinal blood flow and vessel narrowing occur due to hyperoxia, since there is reduced metabolic load following photoreceptor loss that results in increased oxygen from the choroid that can supply the inner retina.25–27 These findings in animal models of RP also provide further support for our finding of a correlation between reduced MFV and macular vision loss, presumably due to progressive loss of macular photoreceptors, in RP patients.

A previous study of OBF measurements using CDI ultrasonography in the CRA of patients with optic disc drusen found significant correlations with severity of visual function loss assessed with HVFs.28 This previous study provides an example of another ocular disease in which OBF in the CRA is reduced with more advanced vision loss, as found in the current study; however, the same study did not find a significant relationship between CRA blood flow and HVF loss across patients with glaucoma,28 likely due to the different mechanisms involved in the optic disc changes (i.e., cupping versus compression) for glaucoma versus optic disc drusen. The previous studies of CRA or retinal blood flow velocity in RP patients consisted of very small sample sizes (i.e., ≤10)5,6,10 and they did not examine the relationship with severity of vision loss; thus, the current findings represent a novel contribution to the literature. It is notable that a previous study of laser speckle flowgraphy revealed that decreased macular blood flow occurs before severe losses of VA occur in RP and also found that macular blood flow was significantly correlated with central visual sensitivity on static perimetry8; however, it is not possible to distinguish between retinal and choroidal blood flow signals using this method.

Despite our efforts to implement a consistent protocol during the acquisition of CDI ultrasonography measures of the retrobulbar arteries, there were challenges to obtain the within-subject measurements in the same locations for the posterior ciliary arteries and ophthalmic artery, which was not an issue for the CRA. In reviewing the results for the posterior ciliary arteries and ophthalmic artery, we found that due to slight positional changes in the eye by the patient, as well as the numerous areas where it could be possible to measure the posterior ciliary arteries and along the long course of the ophthalmic artery, it was difficult to secure a measure in the exact same location at each session. Therefore, given this variability in the measurement locations for these vessels, which we anticipate would affect the OBF values, we did not analyze or include the data for the posterior ciliary arteries and ophthalmic artery in this cohort of RP patients. Future efforts to measure these vessels with CDI ultrasonography should be undertaken with strict or innovative methods to account for this variability.

When testing OBF in normal control subjects, a previous study found interclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.92 to 0.98 for the PSV and EDV in the CRA when comparing results for three examiners who followed a specific protocol for CDI.29 Therefore, we do not believe that the use of three different sonographers in the present study had a significant effect on the assessment of variability. We found no significant difference in the between-visit CoV according to whether the participant’s OBF in the CRA was assessed by the same sonographer at both visits or different sonographers at each visit for PSV (p = 0.70) and EDV (p = 0.41). Our repeated OBF results in Figure 1 demonstrated that there was not a tendency to obtain a greater velocity measurement at the second visit, indicating that there was not a significant effect of learning or experience on the part of the sonographers, as was a concern in a previous study with inexperienced sonographers.30

No previous longitudinal or experimental studies have adequately explored the relationship between within-subject changes in OBF velocity over time and either improvements or reductions in visual function in RP patients. An unexpected finding in our study was that all of our RP subjects, including those with normal foveal or parafoveal visual function, had already developed significantly reduced OBF in the CRA when comparing their PSV and EDV to previously published values in normal controls without ocular disease.10,31.32 All of our RP subjects had evidence of mid-peripheral and perimacular functional loss on visual field testing, indicating photo-receptor loss in those areas, including the regions in which the inner retinal blood vessels are located. Therefore, we propose that significant reductions in CRA flow may occur prior to RP diagnosis and/or shortly thereafter since OBF was already impaired in our RP subjects who had normal central visual function and greater than four years of self-reported visual field loss. Our data also support the hypothesis that much smaller and less meaningful reductions in OBF in the CRA may occur over time with increasing losses in various aspects of visual function. Longitudinal studies of OBF during the period immediately after RP patients are diagnosed are needed to confirm these hypotheses. For the majority of RP patients with several years of visual field loss, OBF measures would be more valuable to determine whether there has been a significant improvement in response to therapy rather than to monitor RP progression. We propose that measures of OBF might be helpful to serve as biomarkers to evaluate the effects of therapeutic options that regulate retinal cytokines, growth factors and other molecules produced by retinal macroglia, which regulate inner retinal blood flow.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of MFV, mean log PSV, and mean EDV in the CRA in relation to AULCSF for the qCSF test in each eye. The drawn lines represent linear regression lines. The R2 value and p-value are for the relationship between MFV and AULCSF for the qCSF test adjusted for age and gender.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of MFV, mean log PSV, and mean EDV in the CRA as an average of both eyes in relation to mean binocular Pelli-Robson log CS. The drawn lines represent linear regression lines. The R2 value and p-value are for the relationship between MFV and Pelli-Robson log CS adjusted for age and gender.

Figure 5.

Scatterplot of MFV, mean log PSV, and mean EDV in the CRA in relation to 10-2 HVF MD score with the size III test target in each eye. The drawn lines represent linear regression lines. The R2 value and p-value are for the relationship between MFV and HVF MD score adjusted for age and gender.

Figure 6.

Scatterplot of MFV, mean log PSV, and mean EDV in the CRA in relation to the mean score for the four most central test locations around fixation in the HVF 10-2 test in each eye. The drawn lines represent linear regression lines. The R2 value and p-value are for the relationship between MFV and HVF mean score for the four most central test locations adjusted for age and gender.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Albert David Woods for assistance with the electrophysiology, Dr. Brennan Nelson for his assistance with data entry, and Robert De Jong at Johns Hopkins University for sharing his expertise related to the measurement and acquisition of CDI of the CRA using ultrasonography, which was valuable in developing a methodological protocol and training our study’s sonographers.

Funding

The National Institutes of Health (NIH): R21 award EY023720 was given to AKB.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Nakagawa S, Oishi A, Ogino K, Makiyama Y, Kurimoto M, Yoshimura N. Association of retinal vessel attenuation with visual function in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;12(8):1487–1493. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S66326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo X, Shen Y-M, Jiang M-N, Lou X-F, Shen Y. Ocular blood flow autoregulation mechanisms and methods. J Ophthalmol. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/864871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt K-G, Pillunat LE, Kohler K, Flammer J. Ocular pulse amplitude is reduced in patients with advanced retinitis pigmentosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(6):678–682. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.6.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falsini B, Anselmi GM, Marangoni D, D’Esposito F, Fadda A, Di Renzo A, et al. Subfoveal choroidal blood flow and central retinal function in retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(2):1064–1069. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beutelspacher SC, Serbecic N, Barash H, Burgansky-Eliash Z, Grinvald A, Krastel H, et al. Retinal blood flow velocity measured by retinal function imaging in retinitis pigmentosa. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249(12):1855–1858. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1757-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grunwald JE, Maguire AM, Dupont J. Retinal hemodynamics in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122(4):502–508. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Battaglia Parodi M, Cicinelli MV, Rabiolo A, Pierro L, Gagliardi M, Bolognesi G, et al. Vessel density analysis in patients with retinitis pigmentosa by means of optical coherence tomography angiography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308925. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami Y, Ikeda Y, Akiyama M, Fujiwara K, Yoshida N, Nakatake S, et al. Correlation between macular blood flow and central visual sensitivity in retinitis pigmentosa. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(8):e644–648. doi: 10.1111/aos.12693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris A. Regulation of retinal and optic nerve blood flow. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(11):1491–1495. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.11.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akyol N, Kukner S, Celiker U, Koyu H, Luleci C. Decreased retinal blood flow in retinitis pigmentosa. Can J Ophthalmol. 1995;30(1):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cellini M, Strobbe E, Gizzi C, Campos EC. ET–1 plasma levels and ocular blood flow in retinitis pigmentosa. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88(6):630–635. doi: 10.1139/Y10-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stalmans I, Siesky B, Zeyen T, Fieuws S, Harris A. Reproducibility of color Doppler imaging. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247(11):1531–1538. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou F, Huang CB, Lesmes L, Feng LX, Tao L, Zhou YF, et al. qCSF in clinical application: efficient characterization and classification of contrast sensitivity functions in amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(10):5365–5377. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stalmans I, Vandewalle E, Anderson DR, Costa VP, Frenkel RE, Garhofer G, et al. Use of colour Doppler imaging in ocular blood flow research. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(8):e609–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naqvi J, Yap KH, Ahmad G, Ghosh J. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound: a review of the physical principles and major applications in Critical Care. Int J Vasc Med. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2013/629378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barry MP, Bittner AK, Yang L, Marcus R, Iftikhar MH, Dagnelie G. Variability and errors of manually digitized goldmann visual fields. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93(7):720–30. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massof RW, Dagnelie G, Benzschawel T, Palmer RW, Finkelstein D. First order dynamics of visual field loss in retinitis pigmentosa. Clin Vis Sci. 1990;5(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ying GS, Maguire MG, Glynn R, Rosner B. Tutorial on biostatistics: linear regression analysis of continuous correlated eye data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017;24(2):130–140. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1259636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanagida K, Iwase T, Yamamoto K, Ra E, Kaneko H, Murotani K, et al. Sex-related differences in ocular blood flow of healthy subjects using laser speckle flowgraphy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(8):4880–4890. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asejczyk-Widlicka M, Krzyzanowska-Berkowska P, Sander BP, Iskander DR. Age-related changes in ocular blood velocity in suspects with glaucomatous optic disc appearance. Comparison with healthy subjects and glaucoma patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchsjäger-Mayrl G, Polak K, Luksch A, Polska E, Dorner GT, Rainer G, et al. Retinal blood flow and systemic blood pressure in healthy young subjects. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239(9):673–677. doi: 10.1007/s004170100333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grover S, Fishman GA, Brown J., Jr Patterns of visual field progression in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(6):1069–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rassam SMB, Patel V, Chen HC, Kohner EM. Regional retinal blood flow and vascular autoregulation. Eye. 1996;10:331–337. doi: 10.1038/eye.1996.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feke GT, Tagawa H, Deupree DM, Goger DG, Sebag J, Weiter JJ. Blood flow in the normal human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30(1):58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campochiaro PA, Strauss RW, Lu L, Hafiz G, Wolfson Y, Shah SM, et al. Is there excess oxidative stress and damage in eyes of patients with retinitis pigmentosa? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;23(7):643–648. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penn JS, Li S, Naash MI. Ambient hypoxia reverses retinal vascular attenuation in a transgenic mouse model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000 Nov;41(12):4007–4013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padnick-Silver L, Kang Derwent JJ, Giuliano E, Narfström K, Linsenmeier RA. Retinal oxygenation and oxygen metabolism in Abyssinian cats with a hereditary retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006 Aug;47(8):3683–3689. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abegão Pinto L, Vandewalle E, Marques-Neves C, Stalmans I. Visual field loss in optic disc drusen patients correlates with central retinal artery blood velocity patterns. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92(4):e286–291. doi: 10.1111/aos.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Founti P, Harris A, Papadopoulou D, Emmanouilidis P, Siesky B, Kilintzis V, et al. Agreement among three examiners of colour Doppler imaging retrobulbar blood flow velocity measurements. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(8):e631–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Németh J, Kovács R, Harkányi Z, Knézy K, Sényi K, Marsovszky I. Observer experience improves reproducibility of color doppler sonography of orbital blood vessels. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30(6):332–335. doi: 10.1002/jcu.10079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baxter GM, Williamson TH. Color Doppler imaging of the eye: normal ranges, reproducibility, and observer variation. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14(2):91–6. doi: 10.7863/jum.1995.14.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rankin SJ, Walman BE, Buckley AR, Drance SM. Color Doppler imaging and spectral analysis of the optic nerve vasculature in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119(6):685–93. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]