Abstract

Little is known about the molecular pathogenesis of congenital nephrotic syndrome in association with primary adrenal insufficiency. Most recently, three groups found concurrently the underlying genetic defect in the gene sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase 1 (SGPL1) and called the disease nephrotic syndrome type 14 (NPHS14). In this report we have performed whole-exome sequencing and identified a new homozygous variant in SGPL1, p.Arg340Trp, in a girl with nephrotic syndrome and Addison's disease. Her brother died previously with the same phenotype and hyperpigmentation of the skin. We reviewed the reported cases and concluded that NPHS14 is a clinically recognizable syndrome. The discovery of this syndrome may contribute to the diagnosis and description of additional patients who could benefit from treatment, genetic counseling and screening for related comorbidities. Until now, patients with congenital nephrotic syndrome associated with primary adrenal insufficiency have been treated as having two different diseases; however, the treatment for patients with NPHS14 should be unique, possibly targeting the sphingolipid metabolism.

Keywords: adrenal insufficiency, glomerular disease, nephrotic syndrome, sphingolipidosis, sphingolipids

Introduction

Congenital nephrotic syndrome (CNS) is a chronic kidney disease whose symptoms appear before and immediately after birth: massive proteinuria with resulting hypoalbuminemia, which in turn causes edema [1]. Patients with a lack of response to standardized corticosteroid therapy are diagnosed with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) [2]. SRNS typically manifests histologically as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), a lesion characterized by sclerosis and podocyte foot process effacement in a few capillary segments of glomeruli [3]. In the last 15 years, variants in >40 genes have been discovered to cause SRNS [2].

Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) is defined as the inability to produce sufficient glucocorticoids and/or mineralocorticoids in the adrenals, which leads to feedback stimulation of the regulatory hypothalamus–pituitary axis and the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone loop [4]. Consequently, a short corticotropin test is recommended to establish the diagnosis. If this is not possible, an initial screening procedure comprising the measurement of morning plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol levels is recommended [5]. Manifestations of adrenocortical insufficiency, or Addison’s disease, include weakness, fatigue, anorexia, abdominal pain, weight loss, orthostatic hypotension and salt craving; characteristic hyperpigmentation of the skin occurs with primary adrenal failure [6, 7]. The spectrum of genetic defects in patients with PAI has increased in recent years with the use of next generation sequencing methods, and variants in ∼50 genes have been reported [4].

Until recently, the molecular mechanisms that could explain the association between CNS and PAI were unknown. However, in March 2017, two articles reported variants in the gene for sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) lyase 1 (SGPL1, OMIM 603729) as the culprit of this phenotype in 27 patients from 12 families [8, 9]. Simultaneously, another research group reported three children from two unrelated consanguineous families with variants in SGPL1 [10]. Herein we report a new family with a new variant in SGPL1 and review the previously reported patients.

Case report

The proband (II-3) was a 3-year-old girl diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome and Addison’s disease (Figure 1A). She was the third child of healthy non-consanguineous parents. She was delivered at term, by cesarean section, after an uneventful pregnancy. Birthweight was 3370 g (50th centile), length 49 cm (50th centile) and the Apgar score was 9. Her development was normal, as she sat and spoke at 8 months of age and walked independently at 18 months of age.

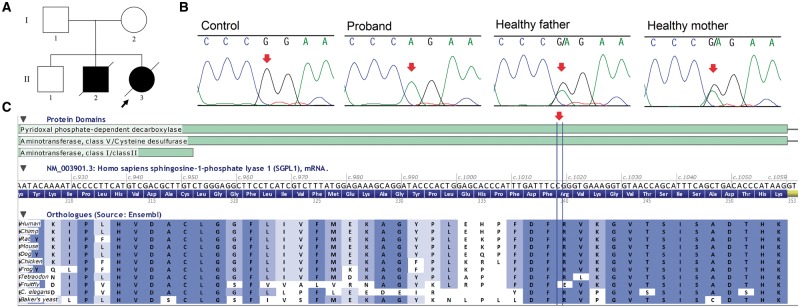

Fig. 1.

(A) Pedigree of the proband´s family. (B) Fragments of sequence chromatograms are shown for SGPL1. Red arrows indicate the position of the variant. (C) Part of the SGPL1 gene showing that the variant is located in a region well conserved throughout evolution (Alamut Visual 2.9.0).

She was hospitalized at 5 months of age with adrenal crisis with vomiting, diarrhea and dehydration. When hydrated, she presented generalized edema accompanied by hyponatremia (109 mEq/L), hypocalcemia (0.94 mmol/L) and hypoalbuminemia (1.1 g/dL) with improvement after she started on steroid replacement of hydrocortisone, fludrocortisone and calcium carbonate (CaCO3). At this hospitalization, she presented convulsive crisis related to hyponatremia. At 6 months of age, urin alysis revealed proteinuria (134 mg/dL) and a protein:creatinine ratio of 7.05. Her ACTH level was very high (4610 pg/mL).

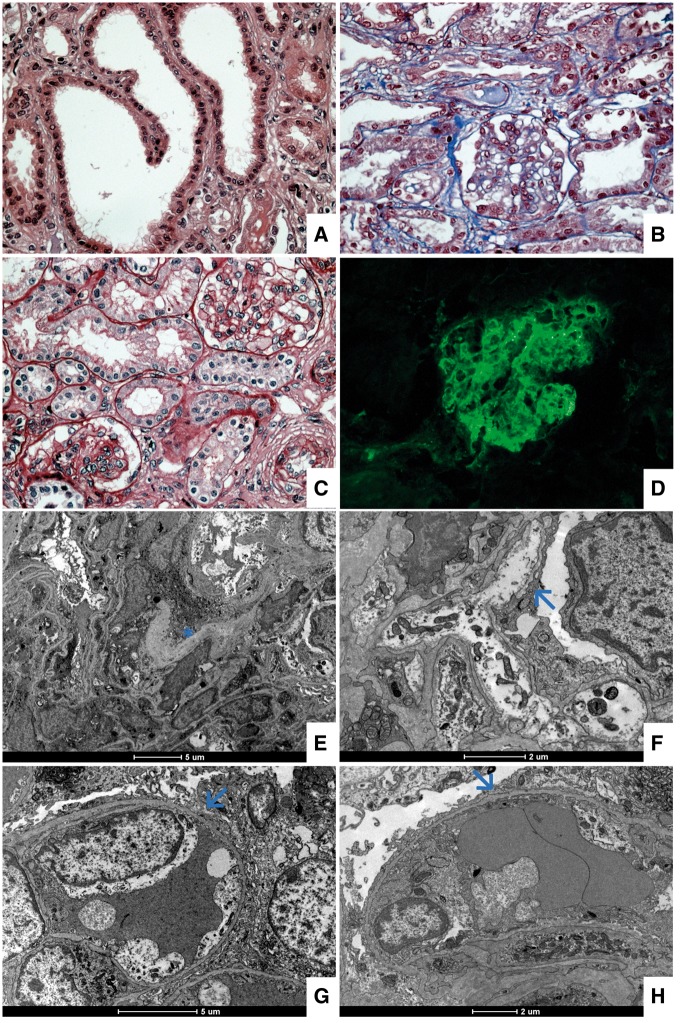

At 8 months of age, renal biopsy showed mild increasing of the mesangial matrix and cellularity. It was noted as focal tubular dilatation (Figure 2A–C). Direct immunofluorescence showed diffuse staining for immunoglobulin M in the mesangial area (Figure 2D). The ultrastructural findings were mainly diffuse foot process effacement and little matrix expansion (Figure 2E–H).

Fig. 2.

Light and immunofluorescence microscopy. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin, magnification × 40, observing focal tubular dilatation. (B and C) Masson's trichrome and periodic acid–Schiff stains, magnification × 40, showing a thin glomerular basement membrane with mild increasing of the mesangial matrix and cellularity. (D) Direct immunofluorescence for immunoglobulin M presenting diffuse mesangial staining. Electron microscopy. (E) Discrete increasing of the mesangial matrix (see asterisk). (F, G and H) Diffuse and severe foot process effacement (see arrows).

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) of the brain at 2 years and 4 months of age was normal. At 2 years and 5 months of age, she was hospitalized again because her renal function worsened (protein level 284 mg/dL, protein:creatinine ratio 18.032) and she presented hypertensive encephalopathy; peritoneal dialysis was started. Total cholesterol was very high (434 mg/dL), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was 242.88 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol was 81 mg/dL and triglyceride was 381 mg/dL. Blood count was normal. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level was 11. 600 µUI/mL, free thyroxine (T4) was 2.53 ng/dL and parathyroid hormone (PTH) was high (220.0 pg/mL). A chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly and an echocardiogram showed mild dilation of the sinus aorta, mild left atrial and left ventricular dilation, left ventricular papillary muscle hypertrophy and small pericardial effusion.

She presented with recurrent peritonitis related to the dialysis catheter (four episodes) and multiple episodes of difficult-to-control systemic arterial hypertension. At 2 years and 9 months of age, the dialysis catheter was changed. At 3 years and 5 months, she was hospitalized with respiratory failure, followed by adrenal crisis and cardiorespiratory arrest. She died 3 months later with bradyarrhythmia and congestive heart failure.

A 7-year-old sibling was healthy (II-1), while a younger sibling presented a similar clinical history (II-2); he has been described in detail in a previous publication [11]. In brief, he presented generalized edema at 3 months of age. At 4 months of age he underwent renal biopsy, which showed mild increasing of the mesangial matrix, immature glomeruli with foot process effacement without slit diaphragm formation, tubular microcystic dilatation and diffuse interstitial fibrosis. Hyperpigmentation of the skin was first noted at 8 months of age. Laboratory evaluation revealed hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia and high ACTH and was diagnosed with associated Addison’s disease. He died at age 1 year and 4 months with diarrhea and vomiting, which in a few hours led to dehydration and shock.

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood of the proband and her parents using a modified salting out procedure [12]. Whole-exome sequencing was performed by the Centre for Applied Genomics, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, using the SureSelect Human All Exon kit V5 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and the HiSeq 2500 Sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Variants were narrowed down using a software developed in-house called Mendel, MD [13] and the ENLIS Genome Research software (Enlis Genomics, Berkeley, CA, USA).

Exome analysis resulted in identification of the candidate missense homozygous variant in SGPL1, located in exon 11, position c.1018C>T (p.Arg340Trp; NM_003901.3). The c.1018C>T variant was not present in the ExAC database. SGPL1 was analyzed by Sanger sequencing as described [14]. The c.1018C>T variant was confirmed in samples from the proband and her parents (Figure 1B). To analyze the impact of the candidate variant, Alamut Visual version 2.9.0 software (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France) was used. It showed that the variant was located in a well-conserved region throughout evolution in SGPL1 orthologues (Figure 1C) and it had in silico pathogenic characteristics as assessed by the prediction programs SIFT (‘deleterious’; score = 0.00), PolyPhen-2 (‘probably damaging’; score = 1.00) and MutationTaster (‘disease causing’; P = 1).

Informed consent was obtained according to current ethical and legal guidelines. The Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital das Clínicas of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (CAEE 22487913.4.0000.5149) and the National Research Ethics Committee (778.728) approved the study protocol. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Discussion

In this study we report a patient with CNS and PAI caused by a new homozygous variant in p.Arg340Trp in SGPL1. To date, 13 different variants in SGPL1 in 14 families have been reported (Table 1). The reported patients present a variable phenotype including CNS and PAI with a combination of skin abnormalities, neuronal dysfunction, immunodeficiency, hypothyroidism, skeletal abnormalities, muscular hypotonia and genital abnormalities [8–10]. Our patient had been treated since she was 5 months old with CaCO3 and we believe that it prevented the development of skeletal abnormalities described in the other patients. In addition, contrary to her brother, our patient expressed only mild hyperpigmentation since she used hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone early.

Table 1.

Clinical features of patients with variants in SGPL1

| Features | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | Total | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Mutation | a | b, c | d | e | f | g | h, i | d | d | j | k | a | l | m | n | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | M | M | F | F | F | M | M | M | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | M | M | M | M | M | F | M | F | F | M | M | M | M | F | |||

| Foetal diseases | FH | g | g | FH | FH | FHg | FH,g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis | 4 y | 7 m | 10 m | 2 y | 1 y | 19 y | 3 y | 2 y | 1 m | 3 m | 1 m | 1 m | 2 m | 18 y | 8 m | 1 y | 1 y | 1 y | 6 m | 10 m | 4 m | 9 y | 6 w | 2 d | 1 w | 4 m | 5 m | ||||||

| Age at renal transplant (years) | 5 | 5/12& | 8 | 5 | ? | 5& | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Age of death | 8 y | 2.9 y | 5 m | 2 m | 6 m | 1 m | 3 m | 7 w | 3 m | 1 y | 3 y | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nephrotic syndrome | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 25/28 | ||||

| Adrenal deficiency | − | +f | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | f | f | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + f | + f | + | f | f | + f | + | + | 24/26 | ||||||

| Skin abnormalitiesa | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 17/18 | ||||||||||||||

| Neurologic defectsb | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 11/19 | |||||||||||||

| Immunodeficiencyc | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | 10/12 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hypothyroidism | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | 7/10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Genital abnormalitesd | + | + | + | + | − | − | 4/6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Skeletal abnormalitiese | + | + | + | − | − | 3/5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muscular hypotonia | + | + | − | − | 2/4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mutations: a, p.Ser3Lysfs*11; b, p.Ile88Thrfs*25; c, p.Arg278Glyfs*1; d, p.Arg222Gln; e, p.Arg222Trp; f, p.Ser346Ile; g, p.Tyr416Cys; h, p.Ser202Leu; i, p.Ala316Thr; j, p.Phe545del; k, p.Ser65Argfs*6; l, p.Arg505*; m, p.Leu312Phefs*30; n, p.Arg340Trp.

M, male; F, female; FH, fetal hydrops; m, months; y, years; w, weeks; d, days; ?, patient had renal transplantation, but the age at which it was performed was not specified; &, performed a retransplant.

+, present; −, absent; blank, not reported.

Skin abnormalities include ichthyosis, acanthosis, hyperpigmentation, scaly lesions and calcinosis cutis.

Neurologic defects include developmental delay, ptosis, strabismus, abnormal gait, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, seizures, microcephaly, corpus callosum hypoplasia, peripheral neuropathy, contrast enhancement of cerebellar structures and bilateral globus pallidus, medial thalamic nucleus and central pons.

Immunodeficienies include lymphopenia, deficiency of cellular immunity, multiple bacterial infection, hypogammaglobulinemia, thrombocytopenia and anemia.

Genital abnormalities include cryptorchidism and hypogonadism.

Skeletal abnormalities include craniotabes, rachitic rosary, asymmetric skull, scoliosis and short stature.

Adrenal calcifications.

Fetal demise.

In most cases, nephrotic syndrome manifested as CNS or in the first year of life shows no response to steroid therapy and rapidly progresses to end-stage renal disease [8]. Histologically, the main finding was FSGS, but diffuse mesangial sclerosis and foci of calcification were also found [8–10]. This syndromic form of CNS was called nephrotic syndrome type 14 (NPHS14) by Lovric et al. [8]. The literature review suggests that the distinctive phenotype in patients with NPHS14 is CNS combined with PAI.

Immunofluorescence experiments in mice revealed that SGPL1 is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum of renal glomerular cells, most specifically in podocytes and mesangial and endothelial cells [8]. SGPL1-deficient mice recapitulated the main characteristics of the human disease with abnormal adrenal and renal morphology [8, 9]. In Drosophila, Sply mutants, which lack SGPL1, led to a phenotype reminiscent of podocyte changes in human nephrotic syndrome [8].

SGPL1 is the intracellular enzyme responsible for the irreversible final breakdown of the lipid molecule S1P, which is cleaved to ethanolamine phosphate and trans-2-hexadecenal [15]. Through G-protein-coupled receptor activation, it has been proven that S1P has important regulatory functions in normal physiology and disease processes, particularly involving the immune, central nervous and cardiovascular systems [16]. Variants in upstream components of sphingolipid metabolism result in the accumulation of excess glycosphingolipids and phosphosphingolipids and lead to inherited disorders known as sphingolipidoses [17]. These conditions include Gaucher disease, Niemann–Pick disease and Fabry disease, among others, and they present highly variable clinicopathologic findings [18]. While a renal phenotype was reported in some of these conditions, adrenal disease has not been described so far [9].

The described human SGPL1 variants were shown to be recessive loss-of-function mutations resulting in reduced or absent SGPL1 protein and/or enzyme activity, subcellular mislocalization of SGPL1 and increased levels of S1P, sphingosine and ceramide species (precursors of S1P) [8–10]. The authors concluded that the pathogenesis of the disease could result from both an excess of intracellular S1P and an imbalance of other sphingoid bases, but also from S1P signaling through the S1P receptors or even a lack of phosphoethanolamine production [8–10].

Treatment

No curative treatment is available for patients with SRNS; considering the 32 patients reported until now with NPHS14 (including the 2 patients reported here), only 6 of them were post–renal transplant, and 2 of these patients required a second renal transplant and 1 died 3 years later [8, 9]. In contrast, adrenal insufficiency is potentially life-threatening: in PAI, mineralocorticoid replacement therapy is necessary to prevent sodium loss, intravascular volume depletion and hyperkalemia [7]. Targeting S1P metabolism may be a form of treatment for patients with NPHS14 [19]. An S1P receptor antagonist [FTY720 (fingolimod)] and a humanized monoclonal S1P antibody (LT1009) are available and they might represent a means to deplete S1P levels in patients with NPHS14 [10, 20, 21]. In addition, SGPL1 enzyme replacement therapy may be a potential therapeutic intervention, similar to the one used for Gaucher disease and Fabry disease [22, 23].

Conclusions

In this report, exome analysis found a new variant in SGPL1 that causes a novel sphingolipidosis, NPHS14. We conclude that this syndrome is clinically diagnosed, combining CNS and PAI, among other features. SGPL1 sequencing should be considered in patients with this phenotype. Although many clinical findings of this syndrome have been documented in other NPHSs, adrenal insufficiency is so far exclusive to NPHS14.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients and their family. Their cooperation made this work possible.

Funding

N.D.L. was supported by a fellowship from Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq). S.D.J.P. receives support as a Scientist 1A of the CNPq. The work was funded by the CNPq and the Fundação de Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Wiggins RC. The spectrum of podocytopathies: a unifying view of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int 2007; 71: 1205–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lovric S, Ashraf S, Tan W, Hildebrandt F.. Genetic testing in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: when and how? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 1802–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benoit G, Machuca E, Heidet L. et al. Hereditary kidney diseases: highlighting the importance of classical Mendelian phenotypes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1214: 83–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flück C. Mechanisms in endocrinology: update on Pathogenesis of primary adrenal insufficiency: beyond steroid enzyme deficiency and autoimmune adrenal destruction. Eur J Endocrinol 2017; 177: R99–R111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal insufficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101: 364–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Addison T. On the Constitutional and Local Effects of Disease of the Supra-Renal Capsules. London: Samuel Highley, 1855 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Charmandari E, Nicolaides NC, Chrousos GP.. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet 2014; 383: 2152–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lovric S, Goncalves S, Gee HY. et al. Mutations in sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase cause nephrosis with ichthyosis and adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Invest 2017; 127: 912–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prasad R, Hadjidemetriou I, Maharaj A. et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase mutations cause primary adrenal insufficiency and steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest 2017; 127: 942–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Janecke AR, Xu R, Steichen-Gersdorf E. et al. Deficiency of the sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase SGPL1 is associated with congenital nephrotic syndrome and congenital adrenal calcifications. Hum Mutat 2017; 38: 365–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pezzuti IL, Silva IN, Albuquerque CT, Duarte MG, Silva JM.. Adrenal insufficiency in association with congenital nephrotic syndrome: a case report. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2014; 27: 565–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF.. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1988; 16: 1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cardenas RGCCL, Linhares ND, Ferreira RL. et al. Mendel,MD: a user-friendly open-source web tool for analyzing WES and WGS in the diagnosis of patients with Mendelian disorders. PLoS Comput Biol 2017; 13: e1005520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Linhares ND, Freire MC, Cardenas RG. et al. Exome sequencing identifies a novel homozygous variant in NDRG4 in a family with infantile myofibromatosis. Eur J Med Genet 2014; 57: 643–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Veldhoven PP, Mannaerts GP.. Sphingosine-phosphate lyase. Adv Lipid Res 1993; 26: 69–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hla T, Brinkmann V.. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P): physiology and the effects of S1P receptor modulation. Neurology 2011; 76: S3–S8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merscher S, Fornoni A.. Podocyte pathology and nephropathy—sphingolipids in glomerular diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014; 5: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Platt FM. Sphingolipid lysosomal storage disorders. Nature 2014; 510: 68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carney EF. Genetics: SGPL1 mutations cause a novel SRNS syndrome. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017; 13: 191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O'Brien N, Jones ST, Williams DG. et al. Production and characterization of monoclonal anti-sphingosine-1-phosphate antibodies. J Lipid Res 2009; 50: 2245–2257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chun J, Hartung HP.. Mechanism of action of oral fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol 2010; 33: 91–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weinreb NJ, Charrow J, Andersson HC. et al. Effectiveness of enzyme replacement therapy in 1028 patients with type 1 Gaucher disease after 2 to 5 years of treatment: a report from the Gaucher Registry. Am J Med 2002; 113: 112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsuboi K, Yamamoto H.. Efficacy and safety of enzyme-replacement-therapy with agalsidase alfa in 36 treatment-naive Fabry disease patients. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2017; 18: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]