Abstract

Background

The correct valganciclovir dose for cytomegalovirus (CMV) prophylaxis depends on renal function estimated by the Cockcroft–Gault (CG) estimated creatinine clearance (CG-CrCl) formula. Patients with delayed or rapidly changing graft function after transplantation (tx) will need dose adjustments.

Methods

We performed a retrospective investigation of valganciclovir dosing in renal transplant patients receiving CMV prophylaxis between August 2003 and August 2011, and analysed valganciclovir dosing, CG-CrCl, CMV viraemia (CMV-PCR <750 copies/mL), leucopenia (<3500/µL) and neutropenia (<1500/µL) in the first year post-transplant. On Days 30 and 60 post-transplant, dosing pattern in relation to estimated creatinine clearance was analysed regarding CMV viraemia, leucopenia and neutropenia.

Results

Six hundred and thirty-five patients received valganciclovir prophylaxis that lasted 129 ± 68 days with a mean dose of 248 ± 152 mg/day of whom 112/635 (17.7%) developed CMV viraemia, 166/635 (26.1%) leucopenia and 48/635 (7.6%) neutropenia. CMV resistance within 1 year post-transplant was detected in three patients. Only 137/609 (22.6%) patients received the recommended dose, while n = 426 (70.3%) were underdosed and n = 43 (7.1%) were overdosed at Day 30 post-tx. Risk factors for CMV viraemia were donor positive D (+)/receptor negative R (−) status and short prophylaxis duration, but not low valganciclovir dose. Risk factors for developing leucopenia were D+/R− status and low renal function. No significant differences in dosing frequency were observed in patients developing neutropenia or not (P = 0.584).

Conclusion

Most patients do not receive the recommended valganciclovir dose. Despite obvious underdosing in a large proportion of patients, effective prophylaxis was maintained and it was not associated as a risk factor for CMV viraemia or leucopenia.

Keywords: CMV prophylaxis, renal transplantation, retrospective analysis, valganciclovir

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and disease continue to be clinically relevant infectious complications for renal allograft recipients. It can result in CMV syndrome, tissue invasive disease, asymptomatic CMV infection [1] with neutropenia or leucopenia, or most often in ‘flu-like illness’ with myalgia and fatigue. Indirect effects of CMV infections are allograft rejection, increased risk of opportunistic infections and reduced allograft and patient survival [2]. Risk factors for developing CMV infection after renal transplantation (tx) are donor positive/receptor negative (D+/R−) serostatus, short prophylaxis duration, higher levels of immunosuppressive therapy and allograft rejection [3].

Recent guidelines recommend for CMV prophylaxis for patients with good renal function (>60 mL/min) a daily dose of 900 mg valganciclovir for 3 months or up to 6 months for high-risk patients [1, 3, 4]. Valganciclovir is a valine ester of ganciclovir, with a 66% higher bioavailability compared with oral ganciclovir capsules. It is a prodrug, and is rapidly absorbed and metabolized to the active form ganciclovir. Valganciclovir prophylaxis with 450 mg daily dose achieved comparable area under the curve (AUC0–24 h) values compared with 1 g oral ganciclovir every 8 h [5]. Dose adjustments depending on the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) are needed as the apparent clearance of ganciclovir is highly correlated with renal function [6]. It is recommended to adjust the valganciclovir dose according to the Cockcroft–Gault (CG) estimated creatinine clearance (CG-CrCl) formula [3, 7]. Key issues facing CMV prophylaxis with valganciclovir are late-onset CMV disease and higher rates of leucopenia or neutropenia, which are common side-effects of valganciclovir [8].

In order to decrease the risk for haematological side effects it is discussed whether low-dose prophylaxis (450 mg) may be used instead of standard dose (900 mg) for prophylaxis treatment [6, 9–13]. Kalil et al. [11] compared in a meta-analysis effectiveness of valganciclovir 900 mg versus 450 mg for CMV prophylaxis. There was no significant difference in frequency of CMV disease but significantly higher risk for leucopenia for the high dose group [11]. However, due to lack of sufficient data especially for high-risk patients, currently valganciclovir prophylaxis with 450 mg daily is not recommended. Major concerns are higher risk for ganciclovir resistance and late-onset disease [3].

Materials and methods

The main objective of this retrospective study was to evaluate the routine prescribing frequency for all GFR classes in relation to under dosing/recommended dosing or overdosing due to the prescribing information/current recommendations. Major outcome objectives were CMV viraemia and occurrence of CMV infection as parameters for the effectiveness and adverse drug reactions like leucopenia or neutropenia.

All adult (≥18 years) kidney transplant patients receiving valganciclovir prophylaxis in our center, were included who were transplanted between August 2003 (= the introduction of routine valganciclovir prophylaxis in our center) and August 2011. Complete 1-year follow-up was available for all patients, except for patients with graft loss or death; at that time patient observation ended. Also, observation ended when CMV viraemia was detected and CMV therapy started. All laboratory data (CMV status, leucocytes, neutrophil granulocytes and renal function), medication history and medical records were reviewed from the transplant database. All patients are closely followed in our clinic for the first year. At each visit, medication is checked and patients are provided with an actual medication list, which guarantees the highest possible data quality on medication. This study was approved by the local ethics committee of the hospital.

From 2004 on, every patient received Bactrim as universal prophylaxis.

Dosing frequency of valganciclovir

At our transplant centre, valganciclovir prophylaxis has been prescribed since the introduction of valganciclovir in 2003 in kidney transplant recipients depending on donor/recipient status. Valganciclovir dosing was adjusted to the estimated creatinine clearance based on CG-CrCl. Except for early start of prophylaxis in the first week post-transplant with once weekly dosing for patients with estimated creatinine clearance <10 mL/min (for this group of patients no dosing recommendations exist), there was no formal site-specific dosing guidance given. As recommended by guidelines, official dosing recommendations were provided to the treating physicians and dose adjustments were to be performed according to the renal function.

According to the medical records in the transplant database, dosing schema and frequency was analysed according to the dosing recommendation in the prescribing information. Dosing schema was divided into underdosing (lower dose prescribed than recommended), recommended dosing (dose prescribed according to prescribing information) or overdosing (higher dose prescribed than recommended). Comparisons were made for CG-CrCl on Days 30 and 60.

CMV viraemia

CMV viraemia was defined as CMV-PCR >750 copies/mL and CMV infection as positive PCR in combination with clinical symptoms. CMV infection was divided into mild infection defined as mild leucopenia and mild general symptoms, and severe infection defined as severe leucopenia colitis, hepatic or other organ involvement. Additionally, we analysed hospitalization caused by CMV viraemia and/or CMV infection.

Leucopenia was defined as mild leucopenia <3500 cells/µL and severe leucopenia <2000/µL. Neutropenia was defined according to NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 as grade 1 (mild neutropenia) with <1500/µL and grade 4 (severe neutropenia) with <500/µL [14].

Statistics

For statistical data analysis, SPSS version 23 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. Continuous variables were shown either as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (range). Categorical variables were analysed by χ2 test and time to event data by log rang test. Group comparisons were made between CMV positive/negative patients, patients developing leucopenia or neutropenia during prophylaxis and patients without leucopenia or neutropenia. Additionally, multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify risk factors for CMV viraemia and side effects. Risk factors (R−/D+ status, sex, age at transplantation, induction therapy, MPA intake, valganciclovir prophylaxis duration, valganciclovir dosing in relation to renal function, steroid doses at Days 30 and 60 post-transplant, tacrolimus c0h, cyclosporine c0h, CG-CrCl at Days 30 and 60 post-transplant) were identified by univariate analysis and were included if P < 0.20. A type I error rate below 5% (P < 0.05) was considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Six hundred and thirty-five patients were included in the analysis and underwent kidney transplantation at the Charité Hospital Mitte, Berlin, from August 2003 to August 2011. All patients received valganciclovir for prevention of CMV disease since the day of transplantation. Evaluation of CMV serostatus revealed 103 (16.2%) high-risk recipients (D+/R−). Most patients received basiliximab as induction therapy (73.7%) (Table 1). Median estimated creatinine clearance was 45.4 mL/min (6.3–290.4 mL/min) on Day 30 and 50.8 mL/min (78.8–154.8 mL/min) on Day 60.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Valganciclovir dosing related to CG-CrCl on Day 30 (n = 606) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | All patients | Underdosing | Recommended dosing | Overdosing |

| Total number | 635 | 426 | 137 | 43 |

| Age at transplantation (years ± SD***) | 51 ± 14 | 49 ± 14 | 54 ± 13 | 55 ± 13 |

| Female, n (%)* | 253 (39.8) | 155 (36.4) | 61 (44.5) | 24 (55.8) |

| Deceased donor, n (%)* | 465 (73.2) | 299 (71.4) | 106 (77.4) | 37 (86.0) |

| CMV high-risk patients (D+/R−), n (%) | 103 (16.2) | 75 (17.9) | 21 (15.9) | 5 (11.6) |

| Prophylaxis duration (days ± SD) | 129 ± 68 | 127 ± 67 | 134 ± 69 | 135 ± 71 |

| Prophylaxis daily dose (mg ± SD***) | 248 ± 152 | 227 ± 119 | 315 ± 210 | 256 ± 160 |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | ||||

| Mycophenolic acid at tx, n (%) | 568 (89.4) | 381 (89.4) | 117 (85.4) | 37 (86.0) |

| Tacrolimus at tx, n (%) | 211 (33.2) | 134 (31.5) | 50 (36.5) | 19 (44.2) |

| Cyclosporine at tx, n (%) | 396 (62.4) | 272 (63.8) | 85 (62.0) | 25 (58.1) |

| Methylprednisolone at tx, n (%) | 601 (99.0) | 424 (99.3) | 134 (97.8) | 43 (100.0) |

| Methylprednisolone at Day 365 post-tx, n (%) | 83 (13.1) | 59 (13.8) | 16 (11.7) | 5 (11.6) |

| Steroid dose on Day 30 post-tx, median (min–max) (mg) | 20 (0–500) | 20 (4–500) | 20 (4–250) | 20 (12–32) |

| Steroid dose on Day 60 post-tx, median (min–max) (mg) | 12 (4–500) | 12 (4–500) | 12 (4–20) | 12 (6–20) |

| Induction therapy | ||||

| Basiliximab, n (%)*** | 468 (73.7) | 347 (81.5) | 91 (66.4) | 29 (67.4) |

| Daclizumab, n (%) | 23 (3.6) | 9 (2.1) | 10 (7.3) | 3 (7.0) |

| ATG, n (%) | 7 (1.1) | 5 (1.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.05) |

| No induction therapy, n (%)* | 137 (21.6) | 70 (16.4) | 37 (27.0) | 11 (25.6) |

P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001.

tx, transplant.

Valganciclovir dosing

During this analysis, a large heterogeneity in valganciclovir dosing became obvious (Table 2 and Figure 1), as in daily routine doctors only weekly adhered to the official prescribing recommendations. Especially in case of improving renal function, dose adjustments were performed too late or even forgotten in a busy outpatient clinic. Duration of valganciclovir prophylaxis ranged from 5 to 365 days (median: 109.0 days), as in some patients prophylaxis was stopped early (e.g. in case of graft loss). In other patients, it was forgotten to stop valganciclovir at the end of recommended prophylaxis.

Table 2.

Overview of dosing recommendations and the actual dose used in relation to CG-CrCl on Day 30 post-transplant

| CG-CrCL: <10 mL/min | CG-CrCL: 10–25 mL/min | CG-CrCl: 25–40 mL/min | CG-CrCl: 40–60 mL/min | CG-CrCl: >60 mL/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended dosing | No dosing recommendation | 450 mg twice weekly | 450 mg every second day | 450 mg daily | 900 mg daily |

| na | 8 | 82 | 154 | 184 | 178 |

| Actual valganciclovir dosea,b (mg) | 112.5±148.8 | 130.8±83.1 | 201.9±96.26 | 267.4±132.2 | 404.1±196.4 |

| Most frequent prescribed dosing recommendation, n (%) | 450 mg once weekly, 4 (50.0) | 450 mg twice weekly, 32 (39.0) | 450 mg thrice weekly, 54 (35.1) | 450 mg thrice weekly, 61 (33.2) | 450 mg daily, 101 (56.7) |

| Second most frequent prescribed dose, n (%) | No drug, 2 (25.0) | 450 mg once weekly, 28 (34.1) | 450 mg twice weekly, 43 (27.9) | 450 mg daily, 30 (16.9) | 450 mg thrice weekly, 30 (16.9) |

Charité transplant centre.

Mean ± SD.

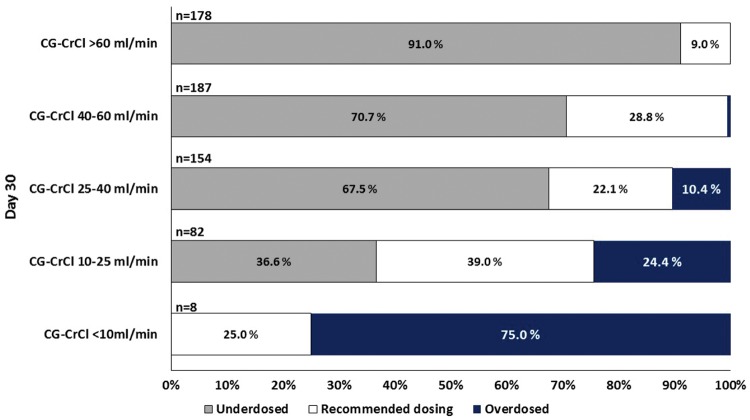

Fig. 1.

Different dosing frequencies according to CG-CrCl classes on Day 30. High variability in dosing frequency was observed for creatinine clearance estimated by CG-CrCl <25 mL/min. Most patients were underdosed who had CG-CrCl >25 mL/min. For CG-CrCl <10 mL/min overdosing was observed, although valganciclovir administration is not recommended due to prescribing information. These patients received valganciclovir 450 mg once weekly. Inside the bars of the diagram the percentage of patients in each group is shown.

First, we analysed daily valganciclovir doses on Day 30. Overall, 70.3% patients (426/606) were underdosed on Day 30 post-transplant, due to insufficient dose adjustment in patients with rapidly increasing renal function. Less than 10% were overdosed (43/609; 7.1%) and only ∼20% of the patients received recommended dosing (137/606; 22.6%). For 29 patients, no data were available on laboratory values or on daily valganciclovir dose at Day 30 post-transplant. Three patients were excluded from analysis due to graft loss within 30 days post-transplant.

Median daily dose (192.9 mg/day, range 0–450 mg/day) was lowest for underdosed patients on Day 30 while for patients with recommended dosing (median: 450 mg/day, range: 0–900 mg/day) and overdosed patients the median daily dose was the same (median: 225 mg/day, range: 64.3–900 mg/day).

There was heterogeneity in prescribing frequency in patients with estimated creatinine clearance between 10 and 60 mL/min (Figure 1). Although no recommendations are given for values below 10 mL/min, in six of eight patients (75.0%) valganciclovir was prescribed once weekly and most patients with low renal function (CG-CrCl <10 mL/min) were overdosed. Similarly, almost 90% of patients with values >60 mL/min were underdosed, receiving only 450 mg/day. For GFR >40 mL/min valganciclovir was prescribed most frequently once daily (53/184, 28.8%) and even more often for GFR >60 mL/min (n = 101/178, 56.7%), while recommended dosing of 900 mg remained low (16/178, 9.0%). Similar results were obtained on Day 60 (data not shown). Dose levels differed largely from the recommendations in the prescribing information. The mean daily dose was lower than the recommended dose for the estimated creatinine clearance for GFR classes 40–60 mL/min and CG-CrCl > 60 mL/min, while higher doses were prescribed for creatinine clearance <10 mL/min (Table 2).

CMV viraemia and disease

Overall, 112 patients (17.6%) were tested CMV-PCR positive at any time during the first post-transplant year (Table 3). Most patients with positive CMV-PCR (59/635; 9.3%) remained asymptomatic. Only 27/635 patients (4.3%) required hospitalization for CMV infection during the first year after transplantation; 3/112 (2.7%) patients developed CMV resistance.

Table 3.

Outcome within 1 year post-transplant (tx) in 635 patients who received valganciclovir prophylaxis

| Outcome | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Graft loss within 1 year after tx | 14 (2.2) |

| Death within 1 year after tx | 13 (2.2) |

| Biopsy-proven acute rejectiona | 112 (17.6) |

| CMV viraemia positive | |

| Total number of patients | 112 (17.6) |

| Asymptomatic | 59 (9.3) |

| Mild CMV infection | 31 (4.9) |

| Severe CMV infection | 22 (3.5) |

| Patients required hospitalization | 27 (4.3) |

| Median time to CMV-PCR-positive result (range) (days) | 87.5 (12–259) |

| Leucopenia during prophylaxis | |

| Total number of patients | 166 (26.1) |

| Mild leucopenia (defined as <3500/µL) | 109 (17.2) |

| Severe leucopenia (defined as <1500 µL) | 58 (9.1) |

| Leucopenia associated with CMV infection | 8 (4.8) |

| Median time to leucopenia, median days (range) | 70 (4–270) |

| Neutropenia during prophylaxis | |

| Neutropenia | 48 (7.6) |

| Together with leucopenia | 41 (6.4) |

| Mild neutropenia (defined as <1500/µL) | 40 (6.3) |

| Severe neutropenia (defined as <500/µL) | 8 (1.3) |

BANFF 09 Category 2, 4.

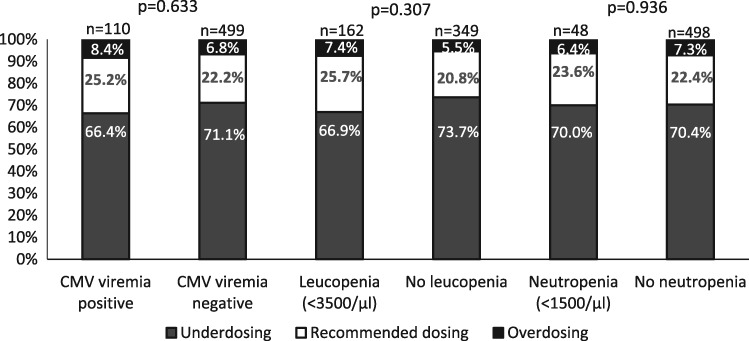

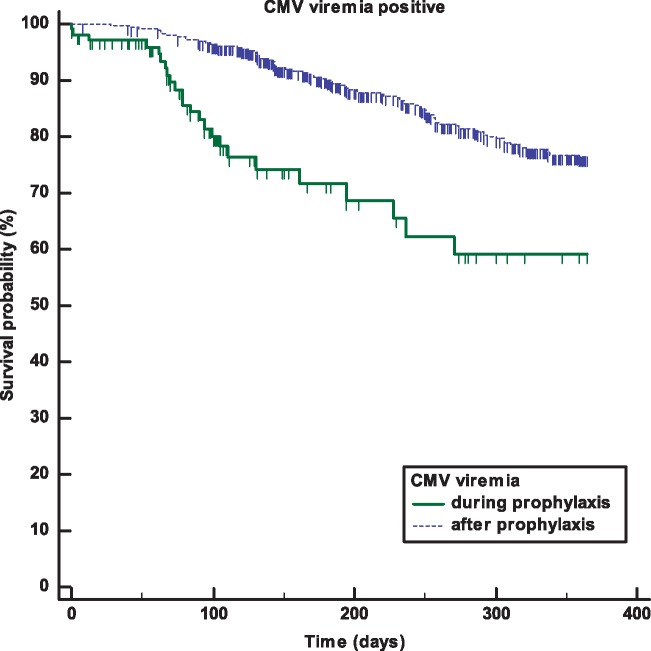

Median time to CMV viraemia was 151 (12–359) days post-transplant. In 23/635 (3.6%) patients, CMV viraemia was observed during prophylaxis with a median of 88 days (12–271) after transplantation (Figure 2). Half of these patients remained asymptomatic (13/23, 56.5%), 4/23 (17.6%) developed mild symptoms while only 6/23 (26.1%) had a severe clinical course. After prophylaxis, 89/635 (14.0%) patients developed CMV viraemia with a median time of 171 (28–359) days post-transplant (Figure 2). Median prophylaxis duration for patients who developed CMV viraemia during prophylaxis was 87 days (min–max: 5–269 days), 25% of patients received 66 days and 75% of patients 126 days of prophylaxis. Patients developing CMV viraemia after prophylaxis received valganciclovir for a median of 90 days (min–max: 5–275), with 25% of patients receiving it for 75 days and 75% of patients for 126 days. There was no significant difference in the severity and hospitalization rate between patients developing CMV viraemia during or after prophylaxis (data not shown). The incidence of patients with CMV viraemia was comparable between underdosed, overdosed and recommended dosing (Figure 3). The results were similar on Day 60 (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Valganciclovir dosing frequency in relation to CG-CrCl on Day 30 post-transplant. The figure shows the dosing frequency in relation to CG-CrCl on Day 30 post-transplant for patients who developed CMV viraemia, leucopenia and neutropenia after Day 30. Most patients received lower doses than recommended. No difference in CMV viraemia, leucopenia or neutropenia occurrence was found.

Fig. 2.

CMV viraemia development within 1 year post-transplant. The figure shows the Kaplan–Meier plot for CMV viraemia development during prophylaxis (n = 23) and after prophylaxis (n = 89). CMV viraemia occurred at a median of 88 days (12–271 days) during prophylaxis while after prophylaxis the median time was 171 days (28–359 days). Median valganciclovir prophylaxis duration for patients developing CMV during prophylaxis was 87 days (min–max: 5–269 days) and a median of 90 days for patients who developed CMV after prophylaxis (min–max: 5–275 days).

Logistic regression revealed that D+/R− patients were at greater risk of developing CMV viraemia (Table 4). CMV-positive patients had significantly shorter prophylaxis duration. A trend to lower CG-CrCl values in CMV-PCR-positive patients was observed. Multivariable logistic regression analysis did not confirm renal function as a risk factor. Correct valganciclovir dosing, underdosing and overdosing did not have a significant impact for developing subsequent CMV viraemia. Similar results were obtained for Day 60. Immunosuppressive medication like steroid doses and MPA intake were not identified as risk factors. Calcineurin inhibitor trough levels were comparable between both groups.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression of risk factors for CMV viraemia

| CMV positive (n = 107) | CMV negative (n = 499) | Odds ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 30 post-tx | ||||||

| High-risk patients (D+/R−)a | 42 (39.3) | 65 (13.0) | 13,401 | 6.651 | 27.000 | <0.001 |

| Deceased donor | 89 (83.2) | 351 (70.3) | 1.417 | 0.726 | 2.766 | 0.307 |

| Underdosinga | 71 (66.4) | 355 (71.1) | 0.870 | 0.474 | 1.597 | 0.654 |

| Recommended dosinga,b | 27 (25.2) | 110 (22.0) | 0.840 | |||

| Overdosinga | 9 (8.4) | 34 (6.8) | 1.108 | 0.390 | 3.150 | 0.847 |

| CG-CrCl (mL/min)c | 36.7 (6.3–120.1) | 47.4 (7.6–290.4) | 0.992 | 0.978 | 1.006 | 0.250 |

| Steroid dose (mg)c,d | 20 (12–500) | 20 (4–50) | 1.032 | 0.980 | 1.086 | 0.233 |

| Prophylaxis durationc | 89.5 (5–275) | 112 (5–365) | 0.983 | 0.977 | 0.989 | <0.001 |

| Age (years)c | 56 (18–76) | 50 (18–78) | 1.019 | 0.997 | 1.041 | 0.094 |

| CMV positive (n=112) | CMV negative (n=522) | Odds ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value | |

| Day 60 post-tx | ||||||

| High-risk patients (D+/R−)a | 42 (37.5) | 65 (12.5) | 17,677 | 7.449 | 41.950 | <0.001 |

| Deceased donor | 90 (80.4) | 372 (71.3) | 1.358 | 0.639 | 2.885 | 0.427 |

| Underdosinga | 86 (76.8) | 405 (77.6) | 1.177 | 0.536 | 2.586 | 0.684 |

| Recommended dosinga,b | 19 (17.0) | 96 (18.4) | 0.668 | |||

| Overdosinga | 7 (6.3) | 21 (4.0) | 0.655 | 0.153 | 2.803 | 0.569 |

| CG-CrCl (mL/min)c | 41.6 (8.8–146.3) | 53.1 (10.5–154.8) | 0.996 | 0.980 | 1.013 | 0.675 |

| Steroid dose (mg)c,e | 12 (4–16) | 12 (4–40) | 0.983 | 0.908 | 1.064 | 0.664 |

| Prophylaxis durationc | 91.0 (5.0–275.0) | 112.5 (7.0–365.0) | 0.978 | 0.971 | 0.986 | <0.001 |

| Age (years)c | 57 (18–76) | 50 (18–78) | 1.027 | 1.000 | 1.056 | 0.053 |

Number of patients (%).

Reference.

Median (min–max).

Converted to methylprednisolone equivalent doses.

Induction therapy included (ATG, basiliximab, daclizumab).

tx, transplant; CI, confidence interval.

Leucopenia

During prophylaxis, 166 (26.1%) patients developed leucopenia, most of them mild leucopenia (<3500/µL) (109/635, 17.2%) (Table 3). Patients who developed leucopenia were overdosed on Day 30 (7.4% versus 5.5%) in comparison with patients without leucopenia (P = not significant).

As a consequence of leucopenia, valganciclovir prophylaxis was stopped in 28/166 (17.0%) patients, dose reductions were performed in 25/166 (15.1%) and in 5/166 (3.0%) patients valganciclovir prophylaxis was paused. However, in most patients (104/166 patients, 62.7%) no changes in prophylaxis treatment were made because leucopenia was mild. For four patients, no data were available. One patient with leucopenia during prophylaxis received filgastrim and developed CMV viraemia 5 months after the prophylaxis ended.

In total, 162/166 (97.8%) patients with leucopenia were on MPA treatment at the time of leucopenia. In those patients, MPA dose reductions were performed in 78/162 (48.1%) patients, MPA treatment was paused in 7/162 (4.3%) patients, and in 69/162 (42.6%) patients no changes in MPA therapy were performed. In one patient, MPA dose was increased and no information on MPA dose adjustments were available in 2/162 patients (1.2%).

The median methylprednisolone dose at the time of leucopenia was 8 mg. The most significant risk factors for leucopenia were low CG-CrCl and D+/R− status. Various valganciclovir dosing on Day 30 or Day 60 was not identified as a risk factor for leucopenia occurrence. Univariate analysis revealed that younger patients and patients with living donors were at lower risk for developing leucopenia but this was not confirmed in multivariable analysis (Table 5). Immunosuppressive medication such as calcineurin inhibitors, MPA intake or steroids were not identified as risk factors for leucopenia or CMV infections.

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression of risk factors for leucopenia

| Leucopenia (n = 143) | No leucopenia (n = 348) | Odds ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 30 post-tx | ||||||

| High-risk patientsa | 39 (26.2) | 42 (12.1) | 2.450 | 1.407 | 4.264 | 0.002 |

| Deceased donora | 126 (84.6) | 244 (68.5) | 1.349 | 0.747 | 2.439 | 0.321 |

| Underdosinga | 99 (69.2) | 255 (73.3) | 1.001 | 0.590 | 1.701 | 0.996 |

| Recommended dosinga,b | 38 (26.6) | 72 (20.7) | 0 | 0.945 | ||

| Overdosinga | 11 (7.7) | 19 (5.5) | 0.864 | 0.339 | 2.198 | 0.758 |

| CG-CrCl (mL/min)c | 35.6 (7.6–105.1) | 51.3 (7.2–290.4) | 0.968 | 0.955 | 0.981 | <0.001 |

| Age at tx (years)c | 62 (22–77) | 49 (18–78) | 1.004 | 0.985 | 1.024 | 0.687 |

| Leucopenia (n = 125) | No leucopenia (n = 358) | Odds ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value | |

| Day 60 post-tx | ||||||

| High-risk ptsa | 36 (28.8) | 42 (12.2) | 2.806 | 1.594 | 4.938 | <0.001 |

| Deceased donora | 104 (83.2) | 246 (68.9) | 1.289 | 0.695 | 2.388 | 0.420 |

| Underdosinga | 94 (74.6) | 94 (74.6) | 1.209 | 0.675 | 2.167 | 0.523 |

| Recommended dosinga,b | 24 (19.0) | 24 (19.0) | 0.762 | |||

| Overdosinga | 8 (6.3) | 9 (2.5) | 1.400 | 0.448 | 4.380 | 0.563 |

| CG-CrCl (mL/min)c | 39.0 (10.8–103.5) | 58.4 (11.9–122.7) | 0.970 | 0.956 | 0.984 | <0.001 |

| Age at tx (years)c | 62 (23–77) | 49 (17–78) | 1.009 | 0.988 | 1.030 | 0.398 |

Number of patients (%).

Reference.

Median (min–max).

tx, transplant; CI, confidence interval.

Neutropenia during prophylaxis

Only 48 (7.6%) patients of the overall cohort developed neutropenia during prophylaxis (Table 3). Most of the patients had mild neutropenia and neutropenia occurred together with leucopenia in 85.4% of all cases. Dosing frequency was comparable between patients with and without neutropenia on Days 30 (P = 0.936) and 60 (P = 0.790). Due to lower incidence of neutropenia no logistic regression was performed.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, valganciclovir dosing pattern was thoroughly evaluated and outcome analysed in a large cohort of renal transplanted patients receiving valganciclovir for CMV prophylaxis. The focus of this analysis was to investigate valganciclovir dose in relation to estimated creatinine clearance (by CG) in relation to the prescribing behaviour of physicians and its impact on CMV viraemia and adverse effects such as leucopenia and neutropenia.

First, we observed large differences in valganciclovir dosing, especially in patients with estimated CG creatinine clearance <25 mL/min. After renal transplantation, GFR values are changing rapidly and the recommended valganciclovir dose was frequently not prescribed. Although it was intended to prescribe valganciclovir according to the product information, this was obviously not achieved in daily routine of a large outpatient transplant clinic. The main problem was insufficient dose adjustments in patients with rapidly improving renal function after transplantation. Obviously, there is a need for better monitoring of drugs with renal elimination, eventually through electronic online information systems. Given the fact that prophylaxis lasted >200 days in some patients, this may indicate that prophylaxis stop was simply forgotten in clinical routine.

In our cohort, ∼70% of patients received a lower than recommended dose of valganciclovir, ∼10% a higher dose and only 20% received the recommended dose. Most underdosed patients had good renal function (CG-CrCl >60 mL/min) and received 450 mg daily instead of 900 mg and 450 mg every second day instead of 450 mg daily in patients with CG-CrCl of 40–60 mL/min. In large prospective studies, 900 mg daily dose of valganciclovir was used for prophylaxis of CMV infection in patients with good renal function. Unfortunately, the efficacy of lower doses was not tested in prospective randomized trials [8, 15]. Even though most patients were underdosed in this study, CMV viraemia frequency was not significantly higher than in the correct dosing group. Logistic regression did not detect underdosing as a risk factor for CMV viraemia. Instead, well-known risk factors, such as high-risk constellation of transplant patients and duration of therapy, were found. D+/R− patients were ∼13-times more likely to develop CMV viraemia. Posadas Salas et al. [10] found that ∼50% of patients received the recommended dose, the other half received lower or higher doses than appropriate, which confirms the difficulty of appropriate dosing in renal transplant patients. Given the good results on outcome, with only 4.3% hospitalizations due to CMV infections, the obvious underdosing had no detrimental effects on outcome. This observation is supported by other recent studies demonstrating a similar effect of low-dose valganciclovir versus recommended dose on CMV infection and an improved outcome of leucopenia occurrence in renal transplant patients [9, 16]. Surprisingly, similar to our findings, higher doses were even associated with a higher prevalence of CMV infections. It was explained by inability of an adequate immune response after drug discontinuation because of the insufficient exposure of the host to low CMV viraemia levels during prophylaxis [9, 17]. A meta-analysis confirmed the effectivness of lower doses for renal transplant patients with different serostatus [11].

Ganciclovir-resistant CMV disease occurs in <1% of solid organ recipients. One of the indicators of drug-resistant CMV disease is that despite treatment the viral load persists, plateaus or even rises [18]. In our cohort, only three patients developed ganciclovir-resistant disease. Comparable results were observed in high-risk kidney transplant patients receiving low-dose valganciclovir prophylaxis treatment [9] or standard valganciclovir prophylaxis dose [19, 20]. Recent reviews and guidelines also suggest low risk of drug-resistant CMV disease with universal prophylaxis most likely due to the highly effective prophylaxis, which prohibits high viral replication and the development of resistance in those patients [3, 18].

Finally, a pharmacodynamic analysis revealed an improved suppression of CMV viraemia and delayed development of CMV viraemia after 900 mg valganciclovir prophylaxis compared with standard oral ganciclovir treatment [21]. Given the fact that ganciclovir AUC0–24 h is comparable between 1 g ganciclovir every 8 h and 450 mg valganciclovir [5], the current valganciclovir dosing recommendations have to be questioned and further investigations on low- versus high-dose valganciclovir for CMV prophylaxis are needed.

Renal function was significantly lower in patients developing CMV viraemia (P < 0.001) but was not identified as a risk factor, which is in line with results of another retrospective analysis in CMV high-risk patients [9] and a post hoc analysis of a randomized trial [10]. In the latter one, patients never achieving a creatinine clearance >60 mL/min were at greater risk for CMV development [10].

Differences in CMV infection frequency were found in patients in relation to the immunosuppressive therapy used. Induction therapy was performed most often with basiliximab but induction therapy was not identified as a risk factor for CMV infection in this cohort. Similar to these findings, another clinical trial did not find any difference between CMV infection incidence between patients who received induction therapy with basiliximab or anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) or no induction therapy [22]. The low frequency of CMV viraemia in our cohort was comparable to a tacrolimus–MPA-treated group where D+/R− patients received prophylaxis therapy [23]. Even lower incidence of CMV infections of <6% was observed in everolimus-treated patients compared with MPA therapy [24, 25] or sotrastaurin treatment [26]. Almost 90% of our patients received MPA. Therefore, comparison to other immunosuppressive medications, such as everolimus, was not considered as appropriate.

Leucopenia, as a side effect, was observed non-significantly more often in overdosed patients and less in underdosed patients. Multivariable logistic regression did not show valganciclovir overdosing as a risk factor for developing leucopenia, instead D+/R− patients and low renal function were identified. Similar to these findings some studies showed that higher valganciclovir doses were associated with a high leucopenia incidence [9, 11, 16, 27]. Only a weak correlation between ganciclovir overexposure and haematologic side effects was found in another study [21].

Due to low renal function, which is common in the early kidney post-transplant period, 7-o-mycophenolic acid glucuronide (MPAG) is accumulated, which can displace mycophenolic acid (MPA) from albumin binding, causing a higher free fraction of MPA and a larger bone marrow suppression [28]. Therefore, the risk of developing leucopenia could be higher in patients with poor renal function taking MPA. However, MPA intake was not identified as a significant risk factor in univariable analysis. Again, the analysis is limited by the fact that ∼90% of patients received MPA. In our study, the incidence for leucopenia development during prophylaxis was higher (∼16.6%) than in another study where patients were treated with MPA but without valganciclovir co-treatment (9.9%) [29]. This indicates patients receiving both drugs are more prone to leucopenia than with MPA alone or without either treatment option. In this context, it is important to mention that also steroid sparing/withdrawal therapy may lead to significantly higher frequency of leucopenia [30, 31]. However, steroid doses were comparable between both groups and were not identified as a risk factor. Bactrim may have influenced leucopenia development as well, but as universal prophylaxis was used; no further analysis on the impact of Bactrim could be performed.

In our cohort, induction therapy with basiliximab, daclizumab and ATG did not influence leucopenia development and was not identified as a risk factor. Leucopenia is seen as a typical side effect of ATG [32]: in one study, more patients in the ATG group than in the basiliximab group developed leucopenia (<2500/mm³) early after transplantation [33]. A retrospective analysis revealed ATG use and African-American race as risk factors for leucopenia [34]. However, because of the predominance of Caucasians and infrequent use of ATG, we could not investigate these risk factors in our cohort.

Similar to another retrospective analysis [35], we identified low GFR as a risk factor for leucopenia. Given the fact that we observed a large heterogeneity in the dose adjustments according to renal function this may indicate some overdosing in patients with low renal function. Also, D+/R− patients were almost three times more likely to develop leucopenia. This patient group may need a close follow-up after transplantation. Although patients in the leucopenia group were older, age could not be identified as a risk factor for leucopenia.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) use was reported in other transplant centres as a frequent (7.8–49%) treatment option for leucopenia [22, 27, 30]. In our cohort, only one patient was treated with filgastrim for leucopenia. The most frequent treatment options for severe leucopenia were MPA and/or valganciclovir dose reductions. In many cases, valganciclovir prophylaxis treatment was paused or stopped, because risk for infection was low at the end of prophylaxis in combination with low steroid doses.

Neutropenia is one of the most common side effects of valganciclovir [8]. The number of patients who developed neutropenia (<1500/µL) in our centre was 46 (7.5%), with only 8 (1.8%) patients with severe neutropenia (<500/µL), which was comparable to another study [8] and lower than in other studies [26, 34, 36]. Most of the patients in our cohort experienced leucopenia (41/635 patients, 6.5%). Although overdosing was observed in the neutropenia-positive group the differences in valganciclovir dosing were not significant (Figure 3). This is in agreement with another study where no statistically significant association of valganciclovir dosing and neutropenia was found [27]. A strong link between neutropenia and MPA was observed in patients on MPA–tacrolimus treatment. Here, a higher incidence was observed compared with patients on MPA–cyclosporine treatment [36]. It was explained by the lower MPA concentrations in patients on MPA–cyclosporine therapy in contrast to MPA–tacrolimus treatment due to inhibition of the enterohepatic recirculation by cyclosporine leading to lower MPA concentrations [36, 37]. MPA dose reductions due to side effects are associated with a higher risk of acute rejections [36, 38]. Therefore, therapy with G-CSF and/or valganciclovir therapy stop may be an alternative if neutropenia is observed [36]. However, more studies investigating the risk of malignancies or other adverse events after G-CSF application are needed [30].

There are some limitations in this retrospective study. Prospective, randomized studies are needed to investigate the safety, tolerability and outcome of low dose versus standard dose for valganciclovir prophylaxis after transplantation in a large cohort. For more precise analysis of valganciclovir dosing, plasma concentrations are needed to establish a link to the pharmacodynamic response, which was not available for this analysis. Some patient characteristics were not evenly balanced in our cohort. Therefore, caution is required, as for any other retrospective study, in the interpretation of the results. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, patient compliance was also not determined.

In conclusion, valganciclovir is considered to have a comparable tolerability and safety profile, even though high variability in dosing patterns was observed in patients with low renal function (<25 mL/min). Standard dose or low dose of valganciclovir was comparable regarding CMV prevention and adverse events, with fewer patients developing leucopenia with application of one dosing step below the recommended one without increasing the risk for developing CMV viraemia.

Funding

This work was funded by Roche.

Conflict of interest statement

O.R. received an honorarium from Roche. M.N. has received two travel grants in 2017 from Pfizer Germany. S.B. has received honoraria and travel grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer and Alexion Astellas. O.S. has received an honorarium from Roche and Astellas. K.B. has received research funds and/or honoraria from Abbvie, Alexion, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Fresenius, Genentech, Hexal, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Shire, Siemens and Veloxis Pharma. D.S., A.H. and H.-H.N. have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1. Kotton CN, Fishman JA.. Viral infection in the renal transplant recipient. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 1758–1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brennan DC. Cytomegalovirus in renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 848–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kotton CN, Kumar D, Caliendo AM. et al. Updated international consensus guidelines on the management of cytomegalovirus in solid-organ transplantation. Transplantation 2013; 96: 333–360. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829df29d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2009; 9 (Suppl 3): S1–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chamberlain CE, Penzak SR, Alfaro RM. et al. Pharmacokinetics of low and maintenance dose valganciclovir in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2008; 8: 1297–1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perrottet N, Decosterd LA, Meylan P. et al. Valganciclovir in adult solid organ transplant recipients: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics and clinical interpretation of plasma concentration measurements. Clin Pharmacokinet 2009; 48: 399–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cockcroft DW, Gault H.. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976; 16: 31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paya C, Humar A, Dominguez E. et al. Efficacy and safety of valganciclovir vs. oral ganciclovir for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2004; 4: 611–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gabardi S, Asipenko N, Fleming J.. Evaluation of low- versus high-dose valganciclovir for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in high-risk renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 2015; 99: 1499–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Posadas Salas MA, Taber DJ, Chua E. et al. Critical analysis of valganciclovir dosing and renal function on the development of cytomegalovirus infection in kidney transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2013; 15: 551–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalil AC, Mindru C, Florescu DF.. Effectiveness of valganciclovir 900 mg versus 450 mg for cytomegalovirus prophylaxis in transplantation: direct and indirect treatment comparison meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52: 313–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bhat V, McIntyre M, Meyers T.. Efficacy and safety of a lower-dose valganciclovir (valcyte) regimen for cytomegalovirus prophylaxis in kidney and pancreas transplant recipients. P T 2010; 35: 676–679 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gabardi S, Magee CC, Baroletti SA. et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose valganciclovir for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in renal transplant recipients: a single-center, retrospective analysis. Pharmacotherapy 2004; 24: 1323–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 4.0. 2009

- 15. Humar A, Lebranchu Y, Vincenti F. et al. The efficacy and safety of 200 days valganciclovir cytomegalovirus prophylaxis in high-risk kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2010; 10: 1228–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heldenbrand S, Li C, Cross RP. et al. Multicenter evaluation of efficacy and safety of low-dose versus high-dose valganciclovir for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in donor and recipient positive (D+/R+) renal transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 2016; 18: 904–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh N. Late-onset cytomegalovirus disease as a significant complication in solid organ transplant recipients receiving antiviral prophylaxis: a call to heed the mounting evidence. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40: 704–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Razonable RR,, Hayden RT.. Clinical utility of viral load in management of cytomegalovirus infection after solid organ transplantation. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26: 703–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Asberg A, Humar A, Jardine AG. et al. Long-term outcomes of CMV disease treatment with valganciclovir versus IV ganciclovir in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2009; 9: 1205–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boivin G, Goyette N, Gilbert C. et al. Absence of cytomegalovirus-resistance mutations after valganciclovir prophylaxis, in a prospective multicenter study of solid-organ transplant recipients. J Infect Dis 2004; 189: 1615–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wiltshire H, Paya CV, Pescovitz MD. et al. Pharmacodynamics of oral ganciclovir and valganciclovir in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation 2005; 79: 1477–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hanaway MJ, Woodle ES, Mulgaonkar S. et al. Alemtuzumab induction in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1909–1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krämer BK, Charpentier B, Bäckman L. et al. Tacrolimus once daily (ADVAGRAF) versus twice daily (PROGRAF) in de novo renal transplantation: a randomized phase III study. Am J Transplant 2010; 10: 2632–2643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tedesco Silva H Jr, Cibrik D, Johnston T. et al. Everolimus plus reduced-exposure CsA versus mycophenolic acid plus standard-exposure CsA in renal-transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2010; 10: 1401–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qazi Y, Shaffer D, Kaplan B. et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus plus low-dose tacrolimus versus mycophenolate mofetil plus standard-dose tacrolimus in de novo renal transplant recipients: 12-month data. Am J Transplant 2017; 17: 1358–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Budde K, Sommerer C, Becker T. et al. Sotrastaurin, a novel small molecule inhibiting protein kinase C: first clinical results in renal-transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2010; 10: 571–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brum S, Nolasco F, Sousa J. et al. Leukopenia in kidney transplant patients with the association of valganciclovir and mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc 2008; 40: 752–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Hest RM, van Gelder T, Vulto AG. et al. Pharmacokinetic modelling of the plasma protein binding of mycophenolic acid in renal transplant recipients. Clin Pharmacokinet 2009; 48: 463–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tedesco-Silva H, Felipe C, Ferreira A. et al. Reduced incidence of cytomegalovirus infection in kidney transplant recipients receiving everolimus and reduced tacrolimus doses. Am J Transplant 2015; 15: 2655–2664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hartmann EL, Gatesman M, Roskopf-Somerville J. et al. Management of leukopenia in kidney and pancreas transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 2008; 22: 822–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Woodle ES, Peddi VR, Tomlanovich S. et al. A prospective, randomized, multicenter study evaluating early corticosteroid withdrawal with Thymoglobulin in living-donor kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant 2010; 24: 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bamoulid J, Crépin T, Courivaud C. et al. Antithymocyte globulins in renal transplantation—from lymphocyte depletion to lymphocyte activation: the doubled-edged sword. Transplant Rev 207; 31: 180–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brennan DC, Daller JA, Lake KD. et al. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin versus basiliximab in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1967–1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luan FL, Kommareddi M, Ojo AO.. Impact of cytomegalovirus disease in D+/R– kidney transplant patients receiving 6 months low-dose valganciclovir prophylaxis. Am J Transplant 2011; 11: 1936–1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liang C, Famure O, Li Y. et al. Incidence and risk factors for leukopenia in kidney transplant recipients receiving valganciclovir for cytomegalovirus prophylaxis. Am J Transplant 2013; 13: 319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zafrani L, Truffaut L, Kreis H. et al. Incidence, risk factors and clinical consequences of neutropenia following kidney transplantation: a retrospective study. Am J Transplant 2009; 9: 1816–1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Gelder T, Klupp J, Barten MJ. et al. Comparison of the effects of tacrolimus and cyclosporine on the pharmacokinetics of mycophenolic acid. Ther Drug Monit 2001; 23: 119–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Knoll GA, MacDonald I, Khan A. et al. Mycophenolate mofetil dose reduction and the risk of acute rejection after renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14: 2381–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]